The night of Friday, 7 March 2014, was one of the rare times when Malaysia’s civil aviation boss’s mobile phone ran out of power.

Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, then chief of the Civil Aviation Department, had been to a family dinner: his niece was to be married at the weekend, and it had been a festive pre-wedding get together, so he was ready for sleep. He put his phone on charge, and went to bed without waiting for it to acquire enough power to start up again.

It was only after pre-dawn prayers next morning that he switched on his phone. A flood of messages started streaming in, and Azharuddin stared at the screen in disbelief as they appeared by the dozen. As he later related in the excellent 2018 British television documentary MH370: Inside the Situation Room: ‘I straightaway told my wife, something is not right.’

That turned out to be the understatement of the year. At that point Azharuddin did not know Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 had vanished into thin air. He also had no idea that MH370 would ultimately cost him his job, four years later.

Azharuddin made some calls and asked some of his senior officers to meet him at the Sama-Sama Hotel where the first press conference was to be held. In a 2018 interview with the New Straits Times, Azharuddin described his thoughts at the time.

‘I said to myself: “My God, a Triple Seven . . . that’s a big jet”. Initially, I thought it was just another airplane that went off our radar scopes . . . but in this industry, we are trained to prepare for the worst-case scenario.’

The air traffic controllers under Azharuddin’s authority should have been trained better for the worst-case scenario; when MH370 disappeared, disbelief, confusion and panic set in.

After advising MH370 to switch to Ho Chi Minh control, and hearing Zaharie acknowledge with ‘Good night, Malaysian Three Seven Zero’ at 1:19am, Kuala Lumpur controllers’ interest in the flight had waned, as they assumed their Vietnamese counterparts were on the case. Their attention was jolted back pretty quickly when, at 1:39am, Ho Chi Minh air traffic controllers said MH370 had not contacted them and, even more alarming, secondary radar contact was lost at BITOD, a waypoint not far after IGARI. The segments below are from the official transcript of the air traffic control communications as published by the Malaysian safety investigation, verbatim except for the removal of some superfluous pauses like ‘eer’ or ‘ahhh’. The transcription may not have been perfect from the sometimes scratchy recordings, and the controllers and other officials were talking in the international language of aviation – English – which was not their native tongue. But the gist of the content and tenor are clear.

Ho Chi Minh air traffic control (HCM): Any information on Malaysian Three Seven Zero, sir?

Kuala Lumpur air traffic control (KL): Malaysian Three Seven Zero already transfer to you right?

HCM: Yeah, yeah, I know at time two zero. But we have no . . . just about in contact . . . after BITOD we have no . . . radar lost with him. The other one here to track identified on my radar.

KL: Okay at what point?

HCM: And no contact right now.

KL: At what point?

HCM: Yeah.

KL: At what point?

HCM: Yeah.

KL: At what point you lost contact?

HCM: BITOD.

KL: BITOD, hah.

HCM: Yeah.

KL: BITOD. Okay. Call you back.

This communication was 19 minutes after Zaharie should have contacted Ho Chi Minh controllers and when they should have taken over responsibility for guiding the flight. The agreement governing air traffic control between the two countries specifies that ‘the accepting unit shall notify the transferring unit if two-way communication is not established within five (5) minutes of the estimated time over the Transfer of Control Point’. That is, if the MH370 pilots had not radioed Ho Chi Minh control by 1:25am, five minutes after the transfer was to have taken place, those Vietnamese controllers should have contacted Kuala Lumpur to ask what was going on. Instead, they waited another 14 minutes. By this time, MH370 was flying back over Malaysia. The controllers in Ho Chi Minh and Kuala Lumpur could not have known that though and, with a disappeared airliner on their hands, they desperately tried to work out what had happened to it.

At 1:41am, Ho Chi Minh again asked for information on MH370, and the reply was that, after IGARI, MH370 did not return to the Kuala Lumpur frequency. Seconds later, a Kuala Lumpur controller made a ‘blind transmission’ to MH370. That’s when there has been a break in communications, and the controller wants to contact an aircraft not with any specific navigational instruction but just to re-establish contact.

‘Malaysia Three Seven Zero, do you read?’ the controller asked.

There was no response. Five minutes after that, the Vietnamese controllers told their Malaysian counterparts they had tried to contact the aircraft numerous times over 20 minutes. Clearly alarmed, the controllers tried other things – making calls on other frequencies including emergency channels, and through other aircraft in the area, asking their pilots to try to reach MH370 by relay, with no result. The note of panic, and positioning of whose fault this looming crisis was, can be detected in the transcript.

At 1:58am, the following exchange took place:

HCM: Could you check back for your side?

KL: Okay we will do that, and the first, at IGARI did you ever in contact with the aircraft or not first place?

HCM: Negative sir, we have radar contact only, not verbal contact.

KL: But no, when aircraft passed IGARI did the aircraft call you?

HCM: Negative sir.

KL: Negative? Why you didn’t tell me first within five minutes? You should have called me.

HCM: After BITOD seven minutes we have no radar contact, then ask you.

As 2:00am came round, it had been 40 minutes since the aircraft had, as far as the controllers could see, vanished from the face of the earth, but then red herrings started to further confuse the situation.

Kuala Lumpur controllers had been in discussions with Malaysia Airlines’ operations centre, and relayed to the Vietnamese that they had been informed MH370 was in Cambodian airspace. But the Ho Chi Minh controllers queried that, saying they had been in touch with their counterparts in Phnom Penh who had no word on MH370 and were just as much in the dark – the flight plan did not call for the aircraft to transit Cambodia. Kuala Lumpur said they would check back with their supervisor.

The misinformation reflected a grievously wrong assumption at the Malaysia Airlines operations centre. The officers there were confident they knew where MH370 was because the aircraft was able to exchange signals with the Flight Explorer aircraft tracking website, or so they thought.

Communications between the Malaysian and Vietnamese controllers sometimes ran into difficulties, the Malaysian safety investigation report found. Kuala Lumpur asked whether Ho Chi Minh was taking ‘radio failure action’ but, the investigation report said, ‘the query didn’t seem to be understood by the personnel’.

Malaysia Airlines operations officers repeatedly expressed confidence they could track MH370 even if radio communications and satellite phone and fax contact was lost, and insisted it was still steadily moving on Flight Explorer. At 2:20am, the Ho Chi Minh controller said that was all very well, but from where they sat, MH370 had ‘disappeared’. The Kuala Lumpur controller replied ‘Disappeared, okay,’ but a couple of minutes later added, ‘Nah, I am not sure, but the company already sent a signal to the aircraft to contact the relevant air traffic control unit’. This refers to another element confusing the controllers – not only did Malaysia Airlines tell them MH370 was still flying and sending tracking signals to Flight Explorer, but that they had sent a signal to the aircraft which the equipment showed had been successfully transmitted, even if there was no reply.

The Kuala Lumpur controllers started to recognise this was more than a glitch, and in turn worried about whether Malaysia Airlines’ operations officers fully appreciated the gravity of the situation. They urged the pursuit of every possible means to contact the pilots, including by satellite phone and fax.

In an exchange at 2:34am, more than an hour after contact was lost, a controller contacted Malaysia Airlines (MAS) operations.

KL: This is MAS Operations, is it?

MAS: Ya ya.

KL: Okay . . . regarding your Malaysian Three Seven Zero . . .

MAS: Herha.

KL: Ho Chi Minh said still negative contact.

MAS: Haa.

KL: And the no radar target at all.

MAS: Okay.

As the night wore on, the Malaysians started using a uniquely Malaysian English quirk: ending sentences with ‘la’. It has various uses, but most often is used for emphasis, to communicate that something is serious and you want to the listener to pay attention. It’s used in a similar way to how in some English-speaking countries one might use the word ‘man’ – ‘If you have your own best interests at heart, you’ll do it, man!’

KL: Can you, I mean is there . . . any possible for the aircraft to answer you?

MAS: Eer . . .

KL: Any way aircraft can answer you?

MAS: Do know . . . you have to try the satcom, la, Sir.

KL: Hmm.

MAS: Will try the satcom and see.

KL: Okay . . . see whether they can, I am sure, whether the position or whether they contact with anyone and the estimate for landing or anything.

MAS: Okay.

KL: Okay and, okay, because, Ho Chi Minh still worry because they have completely no contact at all, either radio or radar.

At 2:36am, when the aircraft had been out of contact for an hour and 15 minutes, Malaysia Airlines operations said MH370 was ‘somewhere in Vietnam’ and gave coordinates based on Flight Explorer to Kuala Lumpur controllers, who in turn relayed them to Ho Chi Minh.

Fuad Sharuji, Malaysia Airlines’ crisis director, got a call at about 2:30am. Being woken up to deal with one problem or another was a regular part of the job, but being told a Boeing 777 had disappeared altogether was not.

Sharuji opened up his laptop, accessed the flight systems, saw there were four other aircraft that were in the vicinity of where MH370 was supposed to be, and to his shock and amazement, found MH370 just wasn’t there at all.

At 2:40am, Malaysia Airlines operations made a satellite telephone call to the pilots – it went unanswered. Malaysia Airlines was starting to realise it had a serious problem – it just didn’t know what.

Just before 3am, 30 minutes after that first phone call, Sharuji declared a code red emergency.

‘You really need three people to agree to declare code red because that is the most serious crisis for us. But because my CEO was not available and the director of operations was not immediately contactable, I had to make the big decision by myself,’ Sharuji told StrategicRISK Asia-Pacific in 2016.

With the airline’s crisis procedure protocol put into action, within an hour most of its top officers had arrived to set up shop in its Emergency Operations Centre in Kuala Lumpur. They looked at the aircraft maintenance log, and it recorded no known technical problems. They checked whether MH370 was carrying any dangerous goods – that too came up blank.

What flummoxed the Malaysia Airlines officials was that Flight Explorer kept showing the aircraft blithely tracking on its planned course towards Beijing.

Then the penny dropped.

Perhaps a senior Malaysia Airlines officer, woken up and called in during the middle of the night, was told by his subordinates something like, ‘It’s all right, sir, Flight Explorer shows MH370 is on course’, to which the senior officer might have replied, ‘You bloody idiots . . .’

In any event, at 3:30am, the Malaysian safety investigation report says, the operations officers at Malaysia Airlines told the Kuala Lumpur control shift supervisor they now realised ‘the flight tracker information was based on flight projection and was not reliable for aircraft positioning’.

In other words, Flight Explorer was not tracking where MH370 actually was in real time at all, but rather where it should be if the flight had proceeded normally.

And it had not proceeded normally for some time. By this stage, MH370 had flown back across the Malay Peninsula to Penang, turned north-west up the Straits of Malacca, gone out of radar range, and at some point turned south on a track to the southern Indian Ocean.

There were other communications among Malaysian and Vietnamese controllers, Malaysia Airlines and controllers in other countries over the next couple of hours. Kuala Lumpur asked Ho Chi Minh, have you contacted Hainan, the next air traffic control sector? Had Hong Kong or Beijing heard anything? Singapore air traffic control, on behalf of Hong Kong, asked if there had been any news of MH370.

At 5:20am, four hours after the aircraft’s disappearance, the Malaysian safety investigation report says when a senior Malaysia airlines captain asked for information on MH370, he opined that based on known information, ‘MH370 never left Malaysian airspace’.

It was in some respects the most sensible, logical observation of the night, and it may be what finally prompted Malaysian controllers to belatedly accept the obvious and act on it. Ten minutes later, the Malaysian control watch supervisor contacted the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre to say Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 was missing. Azharuddin later said the four-hour delay in sounding the alarm was primarily the fault of Vietnamese controllers, who were responsible for the aircraft after the planned handover at IGARI.

The scheduled arrival time for MH370 in Beijing was 6:30am, and Malaysian authorities were still hoping that, by some miracle, it might just land safely and report some malfunctions in the communications systems. Ahmad Jauhari said in MH370: Inside the Situation Room:

‘Six-thirty was the time the aircraft was supposed to land at Beijing, we are still hoping the aircraft will appear. But 6:30 came, and there’s no aircraft. You know, we felt terrible – sick, really.’

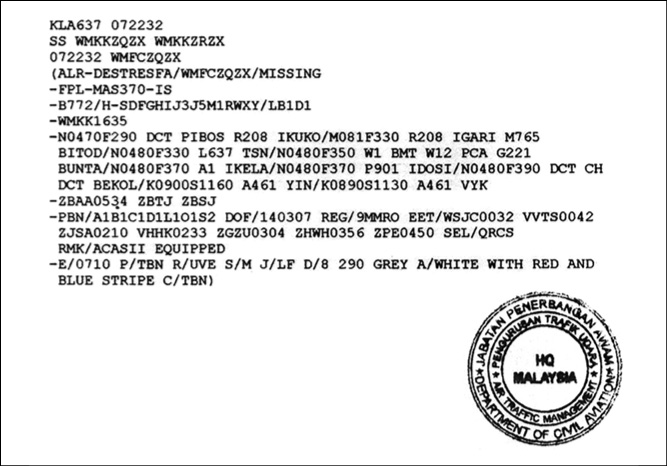

Two minutes later, at 6:32am, the Rescue Coordination Centre issued what’s known as a DETRESFA message, shown below.

FIGURE 2: DETRESFA MESSAGE

© Ministry of Transport Malaysia

DETRESFA is the code word used to designate a ‘distress phase’ in aviation. It’s defined under ICAO protocols as ‘a situation wherein there is a reasonable certainty that an aircraft and its occupants are threatened by grave and imminent danger and require immediate assistance.’ It takes the form of an international coded message – almost impossible for a layman to decipher – with a set of information according to an established protocol. In the MH370 DETRESFA message, the key word is ‘MISSING’. It listed the type of aircraft, the airline and flight number, the aircraft’s registration number 9M-MRO, the last contact at IGARI, and finished off with a brief description of the plane’s livery: ‘GREY A/WHITE WITH RED AND BLUE STRIPE’. The DETRESFA signal went out nearly six hours after MH370 took off, and more than five hours after it disappeared from radar screens around South-east Asia, and from radio and ACARS communications.

At 7:14am, when MH370 would have had only about an hour’s fuel left, Malaysia Airlines operations tried another satellite telephone call to the pilots – it too went unanswered. MH370 had covered most of its track to its end point in the southern Indian Ocean. If, in the Theory One ‘Rogue Pilot to the End’ scenario, Zaharie was still flying the plane, he would no doubt have been thinking ‘it worked . . . I’ve done it . . . they don’t know where I am.’

The Malaysian Air Force hadn’t shown up, the radio transmissions asking him to respond, including from Ho Chi Minh controllers and aircraft flying in the general area where he should have been but was not, showed the authorities were clueless about where he really was and what he was doing.

If he had hijacked the plane, Zaharie must have thought he’d got away with it.