‘STILL, THERE WAS NOTHING. TOTALLY NOTHING’

When Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak ordered authorities to launch a full-on search and rescue mission to find MH370 and the 239 souls aboard, the question was where to look.

The authorities did not have a lot to go on. They did not know what had happened to the aircraft – no distress call had been issued advising of any onboard problems. They did not know where it was – it disappeared over water in the middle of the night, and there were no eyewitness accounts of an aircraft coming down. And they did not know whether or not some or all of those on the flight might still be alive.

What they did know was that at 1:19am, Zaharie had transmitted his final words, ‘Good night, Malaysian Three Seven Zero’, and then the aircraft had passed through waypoint IGARI in the South China Sea. And they knew that moments thereafter, MH370 disappeared from controllers’ screens, meaning its secondary radar transponder must in some way have been disabled. With so little information to hand, the Malaysian authorities decided there was no other logical course of action than to start looking in the last place the aircraft was heard from by radio and secondary radar: the South China Sea around IGARI.

Malaysia’s defence minister and acting transport minister at the time, Hishammuddin Hussein, thought that while the disappearance of MH370 was tragic, finding it or its remains would be relatively straightforward.

‘I wasn’t too worried because you have got fishermen, you have liners,’ he said in MH370: Inside the Situation Room. ‘This is an area that is reasonably easy to identify where, if the plane did go down, where it went down.’ Hishammuddin’s thought process was entirely logical, but as with everything else that followed, logic was overturned several times when it came to MH370.

The international search effort geared up big and fast, with aircraft and ships from Malaysia and its regional neighbours weighing in, along with the US and Australia.

Australia sent two RAAF AP-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft to join the search.

‘This is a tragic mystery as things stand but Australia will do what it can to help get to the bottom of this,’ Prime Minister Tony Abbott said.

China deployed two well-equipped warships, Jinggangshan and Mianyang, adjusted its satellites to help focus in on the search area, and sent more ships.

Vietnam sent surveillance aircraft and ships and, in a move reflecting the cooperative international quality of the effort, allowed China, an on-off enemy, to sail its ships into Vietnamese waters.

The Philippine Navy sent Gregorio del Pilar, Emilio Jacinto, Apolinario Mabini and search and rescue aircraft.

Indonesia announced that it would send five ships, while launching fast patrol vessels straight away.

Singapore’s Air Force got a C-130 Hercules in the air, and two more C-130s on Sunday, and the government dispatched several ships.

The US Seventh Fleet deployed a P-3C Orion craft from Kadena Base in Okinawa, two destroyers with helicopters on board, and a support vessel.

The immediate search area was a 50 nautical mile radius around the last point of contact at IGARI.

It was a massive international search effort, but all it turned up was a series of false alarms.

An oil slick was spotted, a ship was deployed to take samples, but it tested as not being aviation fuel. What looked from the air to possibly be the tail of a Boeing 777 turned out to be a big piece of white canvass happily drifting around.

The crew from a Vietnamese jet reported seeing a ‘possible life raft’ floating in the sea around 400 kilometres off the country’s southern coast, and when helicopters were deployed for a closer look, it was found to be just ‘a moss-covered cap of cable reel’.

The international media rapidly descended on Kuala Lumpur, and Najib decided he himself should head the panel of officials at the press conference they were clamouring for. Scenes in television shows and movies of press conferences with a pack of journalists chaotically jostling to shout out questions above each other are usually over-egged, but this one was exactly that. Already, there had been scores of rumours about what might have happened to MH370, and journalists’ demands for clarification of the facts were insatiable. It was a rare case where the phrase ‘media circus’ was entirely apt.

‘What is the most likely theory?’ a journalist asked.

‘No, that’s too speculative,’ Najib responded. ‘We cannot indulge in speculation at this stage.’

Another journalist wanted to confirm that there was no wreckage, to which Azharuddin responded, ‘We have not found any.’

‘Is there a possibility of terrorism?’ another journalist asked.

‘We are looking at all possibilities, but it is too early to make any conclusive remarks,’ Najib replied.

The international media pack were frustrated – how were they going to file informative stories if the Malaysian officials produced no answers?

Some of the best insights into the thought processes of the government and airline leaders who dealt with the MH370 crisis came in the aforementioned 2018 television documentary MH370: Inside the Situation Room, produced by independent British film group Knickerbockerglory. The filmmakers spent a considerable amount of effort securing access to the key players, including Najib. In the documentary, Najib explained the dilemma for his government.

‘People were hungry for information, but at the same time, as the government, we have to be responsible, and I decided we would only be issuing statements that were verified and corroborated.’

March 8 had been a torrid, difficult day for all concerned, but behind the scenes, different sets of experts were looking at every available piece of data, and as the day moved into night, they were stunned by what they found. Ahmad Jauhari, the Malaysia Airlines chief executive, got a bizarre call from the company’s engineering department.

As mentioned in Chapter One, a fact known to very few people including airline pilots – at least before MH370 disappeared – is as follows. Aside from the communications systems available to the pilots – radio, satellite telephone and fax, ACARS, the secondary radar transponder – airliners are separately equipped with various types of automatic communications transmission systems via satellite. These systems are usually designed to enable aviation engineers and logistics experts to keep track of the status and performance of individual aircraft and their major components. Jet engine manufacturers and the airline engineers who maintain them, for example, like to get data from the engines they may have to service or replace directly, as it can help speed up their processes.

What his engineers told Ahmad Jauhari left him gobsmacked, but with renewed hope. While the last radar transponder signal had been received at 1:21am, the automatic satellite signals from another transmitter on MH370 were received until well after 8:00am – another seven hours.

What could it possibly mean? Could MH370 have flown on after it disappeared and landed somewhere safely? That time frame was close to when the aircraft would have reached fuel exhaustion – could that mean it simply flew until the tanks ran dry?

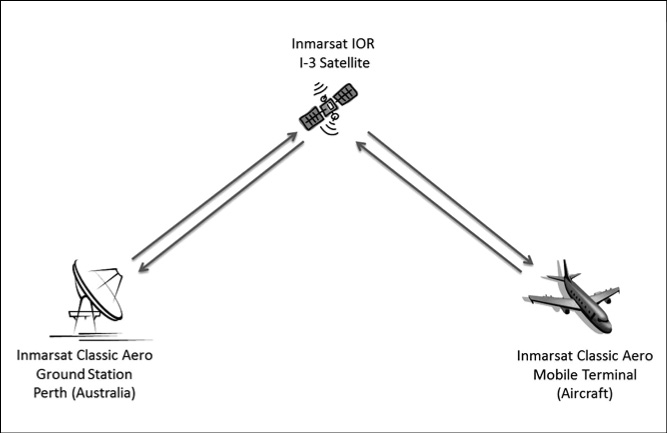

Because of the uncertainty of the implications, this was one piece of information the Malaysian leadership decided to not immediately make public; the fear again was that it could create false hopes among the families. The automatic satellite signals work roughly like this: a transmitter on the aircraft – in this case the Rolls Royce engines – sends an electronic ‘handshake’ to a satellite, and that signal is relayed to a ground station and in turn to the client seeking the data.

FIGURE 3: BASIC SATELLITE COMMUNICATION

© Inmarsat / Australian Transport Safety Bureau

The electronic satellite ‘handshakes’ from MH370 were roughly hourly. In this case, the satellite relaying the data on the day in question was one positioned in geostationary orbit pretty much plumb bang over the middle of the Indian Ocean. That satellite belonged to the British company Inmarsat. What the Malaysians then asked Inmarsat to do was nigh impossible: use the satellite data to find MH370.

Inmarsat told the Malaysians it was not going to be easy – the satellite was not designed to track anything, just relay communications – but they would give it their best shot.

As this was going on, another astounding discovery was unfolding. As discussed in Chapter One, there are two main types of radar for the purposes of tracking aircraft: secondary (transponder), and primary. While MH370’s secondary transponder stopped broadcasting at 1:21am, primary radar systems in Malaysia and its neighbours were operating constantly. They can’t tell which aircraft is which – sometimes they can’t even know for sure if the bounce-back ‘blip’ on the screen is actually an aircraft or an anomaly. But primary radar can detect something in the air, and in modern systems, the reports are automatically recorded and can be played back.

The Malaysian military had been going over those recordings from its radar installations. General Rodzali Daud, Malaysia’s Chief of Air Force at the time, got an astounding message from the operational commander, saying a strange track had shown up. The track started where and when MH370 had disappeared at IGARI, then headed back over the Malay Peninsula towards Penang, and then north-west up the Straits of Malacca.

If the aircraft making that track had been MH370, the implications were enormous. Could MH370 have experienced some technical problems and turned back, having suffered some serious malfunction which damaged its communications systems? In that case, why did it not land at Kota Bharu or Penang? Or could it be a coincidence – was the track that of some private jet aircraft with a flight plan filed but yet to be matched? Or could it just be what are known in the radar profession as ‘ghosts’ – false readings that can be produced by anomalies such as reflections off clouds? But if the mysterious track had indeed been made by MH370, it meant it had not come down in the South China Sea – it was more likely on the other side of the Malay Peninsula, possibly in the Straits of Malacca or farther north.

It was a huge conundrum for the Malaysian authorities. What to do: take the military radar track to be that of MH370 and drop the search in the South China Sea and move it to the Straits of Malacca? Stick with the current search zone and wait until there was more certainty about what the military radar really did show? How long could that take?

The government concluded there was only one responsible way forward.

‘There was no textbook to say what was the correct thing to do, but I wanted to find the plane at all costs, so I immediately instructed for an additional search and rescue to be done on the western side,’ Najib said in MH370: Inside the Situation Room. ‘But because they were not sure it was MH370, we had to continue the search in the South China Sea.’

The result was that what was already an extraordinary international effort to find a missing aircraft became even more ambitious. At its height, 42 ships and 39 aircraft from 12 countries were scouring huge tracks of the Straits of Malacca to the west, and the South China Sea to the east. As the search zones were divided up and assigned to the ships and aircraft of different participating countries, highly sophisticated new aircraft like the US Air Force Poseidon P-8 were looking in one sector, while ageing Soviet-era Vietnamese Air Force aircraft were looking in others.

But there was no sign of MH370, not a skerrick.

After a few days of searching both areas, Hishammuddin and other officials fronted an increasingly hostile international media. It was a tough performance to pull off given the inherent nature of the script.

‘Where is the focus of your search, can you confirm if the plane has turned back?’ a journalist asked.

‘We are focusing both in the South China Sea, and in the Straits of Malacca,’ Hishammuddin replied.

Another journalist put to Hishammuddin, ‘You’re searching east, you’re searching west, you don’t seem to know what you have seen on radar, and it has taken you now, five days later . . . this is utter confusion now, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t think so,’ Hishammuddin replied. ‘I think it is far from it. It is only confusion if you want it to be seen to be confusion. We have made it very clear that we have been very consistent in our approach . . . we are still not sure it is the same aircraft, that is why we are searching in two areas.’

One question was: ‘Why is it that Malaysia lacks the transparency and are very stingy with information?’

Hishammuddin came up with a rather elegant response to that one: ‘Because the information is far between.’

The media contingent was obviously doubtful the full story was being told. A journalist who sounded American asked, ‘Why not release the raw radar data? Are there any plans to do that?’

There weren’t. It’s a controversy to this day, with associations representing the MH370 families and international aviation professionals demanding the release of all the available primary information.

Hishammuddin told the filmmakers of MH370: Inside the Situation Room: ‘Behind the scenes there were massive discussions between me and my military generals and the security experts to discuss what we are able to reveal . . . Military radar will never be released. Try and get that from the Pentagon.’

The search planes kept flying out to the east, and flying out to the west, the search ships kept sailing around looking for anything to do with MH370, and no-one found anything.

Najib could not believe it.

‘I was completely flabbergasted,’ he said in MH370: Inside the Situation Room. ‘I had countless sleepless nights, thinking, where on earth is the plane? We had the best minds to advise us and still, there was nothing. Totally nothing.’

The search effort was in desperate need of a new lead, and it came a couple of days later from Inmarsat, and took the whole story into another new, extraordinary direction. Azharuddin got a call from the London-based British satellite company, which had been poring over the raw data from the satellite transmissions.

The Inmarsat official had some stunning news: they might be able to provide some guidance on where MH370 went. Azharuddin asked if a delegation from Inmarsat could come to Kuala Lumpur on the next available flight, and they were picked up by his officers and brought straight to the Sama-Sama Hotel where he was staying.

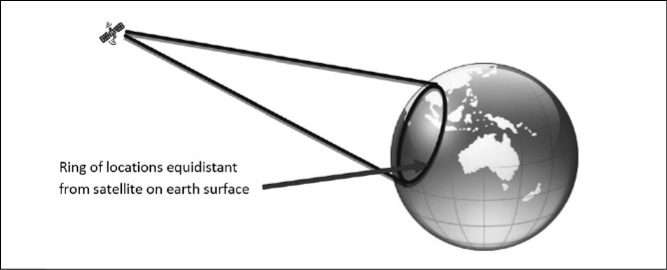

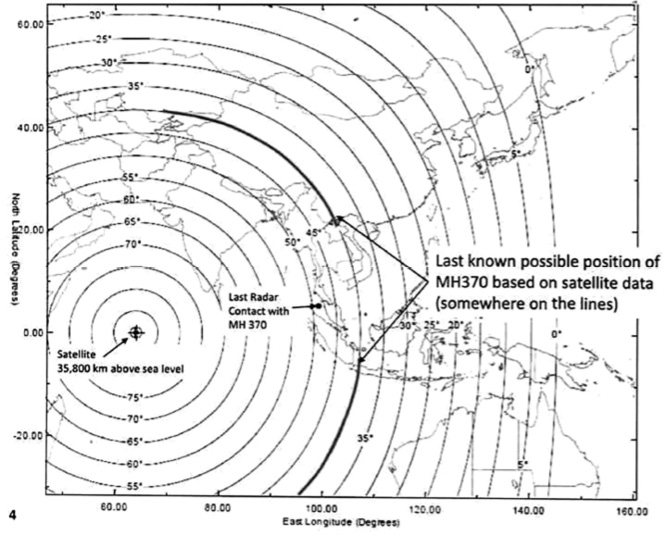

The Inmarsat officer talked about all sorts of strange things like burst frequency offset, burst timing offset, and the first, second, third, right up to Seventh Arc. Even to aviation experts such as Azharuddin, it was esoteric to the point of being alien, but once explained, the implication was huge. By analysing the seven roughly hourly electronic satellite ‘handshakes’ from MH370, and looking at how long they took to go out and come back between the aircraft and the satellite, Inmarsat had been able to establish seven rings around the Asia-Indian Ocean region upon which the aircraft would have been at the time of each of the seven handshakes.

So it was not the actual location of the aircraft that Inmarsat could provide – the satellite was not tracking MH370 per se. Nor were the rings even the actual flightpath of the aircraft; they were the arcs of distance somewhere along which the aircraft would have been from the satellite at the hourly handshakes.

FIGURE 4: POSITION RING DEFINED BY BURST TIMING OFFSET MEASUREMENT

© Inmarsat / Australian Transport Safety Bureau

It was all rather confusing, but the takeaway message was huge. Working with the British government’s Air Accident Investigation Branch, Inmarsat had plotted the maximum endurance distance the aircraft could have travelled from its last known position either way along the arc indicated by the seventh and last satellite handshake – what would come to be known as ‘the Seventh Arc’. From that it was possible to size down MH370’s possible resting place to two bands, one curving north-west and one south-west.

The first problem was that Inmarsat could not say which way along the Seventh Arc MH370 flew – north to central Asia, or south to the southern Indian Ocean. The second problem was that both bands were massive – the one to the north-west extended all the way across central Asia to the Caspian Sea; the one to the south-west a good part of the way towards Antarctica.

It was, like the military radar tracking, a difficult one to explain convincingly to the media and the families. On 15 March, a week after MH370 disappeared, Najib again took it upon himself to drop the bombshell to the media.

‘Today we can confirm MH370 did indeed turn back consistent with deliberate action by someone on the plane,’ the PM said. ‘We are unable to confirm the precise location of the plane; however, the aviation authorities have determined the plane’s last communication with the satellite was in one of two possible corridors.’

The ‘corridors’ were, in fact, huge swathes of the globe. The southern corridor just covered vast, empty ocean. The northern corridor spanned millions of square kilometres of land across a dozen countries from Vietnam to Turkmenistan.

FIGURE 5: THE CORRIDORS OF MH370’s LAST COMMUNICATION WITH A SATELLITE

© Ministry of Transport Malaysia

There was no way one could possibly even think of mounting a search and rescue operation systematically across such huge areas. The only way forward would be via a process of elimination, and a doable exercise would be to see if any of the countries in the northern corridor had picked up MH370 flying through their territory. Najib contacted national heads of government along the northern corridor to ask them to check to see if an aircraft matching MH370’s description had been detected moving through their territory.

Along the southern corridor, there was nothing but ocean, and the closest country to it was Australia. On 18 March, the Australian government agreed to start looking at an enormous stretch, based in only very loose terms in the early days on where the satellite data indicated MH370 might be.

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) said the search zone would cover 600,000 square kilometres of ocean in an area 3000 kilometres south-west of Perth. Initially, it was just a needle-in-haystack token operation: one RAAF Orion began searching the Indian Ocean to the north and west of the Cocos Islands, while another Orion continued to search west of Malaysia.

As part of the switch in the search strategy, the hunt in the South China Sea was called off – whatever else it did, MH370 was now fully confirmed as having turned back over Malaysia.

Since it was clear that whichever way MH370 had gone, it was at least for the first couple of hours under the control of a pilot, attention again came back to the possibility of a hijacking. The Royal Malaysian Police investigated what was known about both the passengers and crew, with assistance from Interpol. No-one suspicious emerged. The two Iranians travelling on stolen passports were looked at particularly carefully, but were also cleared of any known terrorist links; their sole motive seemed to be illegal immigration to Europe by a roundabout route.

The next piece of the MH370 jigsaw again came from Inmarsat, just over two weeks after MH370 disappeared. The tech-heads at the British satellite company had kept grinding down the data and working out new ways to unlock its meaning. They posed the question: what do the automatic satellite handshakes from similar flights going roughly along the northern and southern corridors – or as close to them as can be reasonably compared – indicate might be different between them?

Inmarsat’s conclusion was, if correct, effectively the final death knell for the 239 people on board MH370: the analysis indicated the aircraft had flown not north-west over land, but south to the middle of nowhere in the southern Indian Ocean where it could only have run out of fuel.

Najib was shocked, saw the implications immediately, and knew an appalling decision and announcement lay before him.

On 24 March, Najib again confronted the international media pack.

‘This evening, I was briefed by the representatives from the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch. They have been able to shed more light on MH370’s flight path. Inmarsat and the AAIB have concluded that its last position was in the middle of the Indian Ocean west of Perth.’

Then, Najib delivered the coup-de-grâce.

‘This is a remote location far from any possible landing site.’

Some family members at the venue had to be taken out on stretchers.

Relatives of those on board received the news in a Malaysia Airlines SMS message which said: ‘We have to assume beyond all reasonable doubt that MH370 has been lost and none of those on board survived.’

Despite the fact the Malaysian leaders knew how dim the chances were of finding any floating wreckage – let alone survivors – in the tumultuous seas of the southern Indian Ocean more than two weeks after the aircraft disappeared, the search had to be moved there exclusively, with the hunt anywhere else now concluded to be pointless. The Malaysians formally asked the Australian government if it would take over the major responsibility of leading such a search, and Tony Abbott agreed.

Although the Malaysian government’s involvement in the hunt for MH370 went on for another four years and notionally continues to this day, this point marked the end of the first chapter in the saga where it had made every call on its own. In MH370: Inside the Situation Room, Hishammuddin said, ‘Tell me one government that would not be confused.’ It would be hard to argue against Hishammuddin’s assessment: the bizarre initial disappearance of MH370 over the South China Sea, the primary radar tracking showing it turned back over Malaysia, the satellite data showing it turned again, south, and kept flying for hours without any communication to oblivion in the southern Indian Ocean – it was all completely inexplicable and confusing.

Hishammuddin said, ‘We know that we have tried our best, that is all that we can say. We have done our best, and we will continue to do our best.’

Next, it was up to the Australians to try.