The Buddhist paintings of the Goryeo period (918-1392) were recognized as masterpieces throughout contemporary East Asia thanks to their brilliant colors, elegant forms, rich ornamentation, lucid brushwork, and religious symbolism. Fortunately, many of these works survive today. More than 100 scrolls and murals have been located both in Korea and abroad (the great majority are in Japan), and even more paintings are likely to be discovered in the future in Korea and Japan.

An understanding of the changing themes and stylistic characteristics of Goryeo Buddhist paintings is vital to grasping Korean art history as a whole. At the same time, such an understanding also helps deepen our knowledge of Buddhist art in other Asian countries during this period, especially China. Through these religious paintings, we can also look into the general cultural life of the Korean people during the medieval period, when Buddhism flourished as the state religion for four centuries.

THEMES AND STYLES

Goryeo Buddhist paintings are distinguished by several characteristics. First, they could be called “aristocratic paintings” since they were painted to suit the tastes of the aristocratic class. The royal and noble households of Goryeo patronized Buddhism, and their wealthy members sponsored the production of many ritual paintings of outstanding quality. Naturally, these paintings reflected the luxurious tastes of their benefactors, who in the early days of the dynasty were usually local gentry, but who later included aristocrats in the capital who rushed to support pious projects. The paintings were often produced as a gesture to pray for peace in the kingdom and prosperity for the royal household. As time passed, however, more paintings were executed to invoke the well-being and power of the individual benefactors and their families.

This trend grew in importance during the latter half of the Goryeo period, particularly under the de facto government of the military. Accordingly, Buddhist paintings catering to the powerful nobility came to represent the general aesthetic tendency at this time.

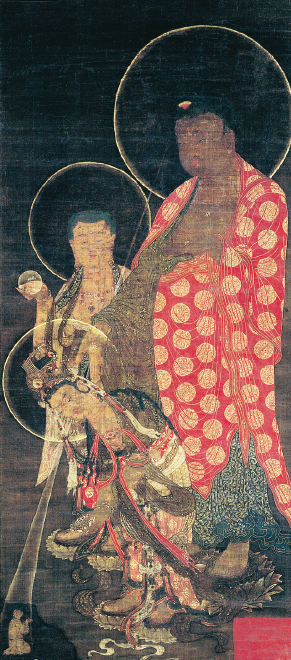

Amitabha Triad. Numerous pictures of Amitabha were produced under the patronage of the royal and aristocratic families, who wished to perpetuate their power and wealth forever. (14th C, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art)

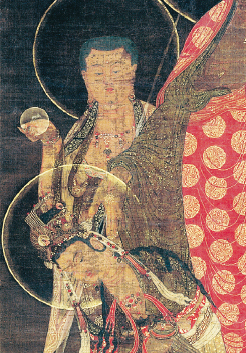

Suwolgwaneumdo, The Water-Moon Avalokitesvara. The Water-Moon Avalokitesvara portrays Gwanseeum in a meditative posture, looking over water by moonlight. (14th C, Amore pacific Museum of Art)

Second, paintings illustrating the contents of two major scriptures—Hwaeomgyeong (The Avatamsaka Sutra) and Beobhwagyeong (The Lotus Sutraor), The Saddharma Pundarika Sutra—prevailed, since the majority of Korean Buddhists in early Goryeo followed Gyojong, the Textual School, which emphasized reading, rather than Seonjong, the Contemplative Zen School, which focused on cultivating the spiritual essence of the human mind for a sudden enlightenment. These scriptures were illuminated with meticulously executed frontispieces.

Among the icon paintings derived from the Hwaom Sect, a bodhisattva triad of Vairocana (Biro), Manjusri (Munsu) and Samantadhadra (Bohyeon), which was enshrined at Beopwangsa Temple, are most deserving of our attention. Both Beopwangsa and Buseoksa Temples housed portraits of high priests who propagated the Hwaeom doctrine in Korea. Another popular theme for paintings from the Avatamsaka Sutra was the episode involving Sudhana, or Seonjae Dongja the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. In a pilgrimage to attain enlightenment, the boy Sudhana visited 55 different teachers, eventually receiving the greatest help from Avalokitesvara, or Gwanseeum Bosal, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

The Maitreya Triads at Geumjangsa and Geumsansa Temples as well as a frontispiece for Mireukgyeong (The Maitreya Sutra), attest to the teachings of the Beopsangjong or Yogacara sect, which relied mainly on The Lotus Sutra as its doctrinal source.

It is only natural that many Buddhist paintings dating to the second half of the Goryeo period depict themes from the Contemplative School, since that became the mainstream of Buddhism at that time. Portraits of Dharma and revered Zen masters, as well as diagrams of the various sects, were among the most popular paintings during these years.

Third, numerous pictures of Amitabha (Amitabul, the Buddha of the Western Paradise), Avalokitesvara, and Tsitigarbha (Jijang, the Ruler of the Underworld) with the Ten judges of Hell (Siwang) were produced under the patronage of the royal and aristocratic families, who wished to perpetuate their power and wealth forever, both in this world and beyond. These pictures had been popular icons among Korean Buddhists since the Unified Silla period (7th-early 10th centuries) but had never been so widely distributed.

The Goryeo Amitabha paintings portrayed a variety of images: a single deity seated upon an elaborate architectonic throne, a triad of standing or seated deities, or Amitabha seated on a throne with his two attendant bodhisattvas standing on either side. One prominent piece from this genre is a hanging scroll portraying Amitabha accompanied by his two main attendants, Avalokitesvara and Mahathana (Taeseji), representing the principle of mercy and the conceptualization of power, respectively. The painting was enshrined at Paeguriam Hermitage on Mt. Powol. Also worthy of note are a portrait of Amitabha dedicated to Prince Sohyeon (1612-1645), a picture of Amitabha with eight bodhisattvas at Sujeongam Hermitage on Mt. Odaesan, and a depiction of Avalokitesvara in a white robe housed at Gukjeongsa Temple.

Other popular types of Buddhist paintings from this period include: naeyeongdo, showing Amitabha guiding worshippers to his Western Paradise; Gwangyeongpyeonsangdo, or The Frontispiece for the Sutra on the Meditation of Amitayas, Suwolganeumdo (The Water-Moon Avalokitesvara), portraying Gwanseeum in a meditative posture looking over water by moonlight; and Jijangbosaldo, depicting Ksitigarbha, the Ruler of the Underworld.

Throughout the Goryeo period, an enormous number of ritual paintings were produced for use in large-scale temple ceremonies supplicating deities such as Vajradhara (Inwang) and Indira (Jaeseok) for assistance in repelling foreign invasions and controlling internal revolts. These paintings were also painted on the gates of various temple structures.

Fourth, the writing of sutras by hand (sagyeong) and carving of woodblocks (mokpangyeong) were both considered sacred acts by Buddhists throughout East Asia, including Goryeo. Aside from the promulgation of the Buddhist faith, the devotees believed that through these meritorious practices they would be guaranteed rebirth in a higher state or in paradise and would be freed from all worldly distress, such as illness and suffering.

The hand-copying and illuminating of Buddhist manuscripts attained remarkable artistic heights during the Goryeo priod. Illuminated sutras were lavishly embellished with the most precious materials available: gold and silver mulberry paper dyed in deep indigo or purple. Historical records indicate that the Royal Sutra Scriptorium employed skilled professional calligraphers to produce valuable manuscripts. The scriptorium was divided into two sections: the Scriptorium of Gold Letters (Geumjawon); and the Scriptorium of Silver Letters (Unjawon). The sumptuous manuscripts were commissioned by the palace and aristocratic families in supplication for the prosperity of the kingdom and their own personal happiness and longevity. The sheer quantity and quality of the extended sutra manuscripts from the Goryeo period are considerable. Neither the skill nor volume was ever duplicated again.

The hand-copying of scriptures was eventually replaced by bulk printing following the discovery of woodblock printing. The woodblocks were often composed of two sections: a picture filled the upper half, illustrating the content of the text in the lower half. In the case of important scriptures, such as The Avatamsaka Sutra, each section of script was illuminated by an additional frontispiece. Metal plates replaced woodblocks after the invention of metal type and grew increasingly popular, eventually outnumbering hand-drawn pictures during the Joseon period (1392-1910).

Fifth, the great majority of Goryeo Buddhist paintings were produced in the form of murals. In fact, most works recognized as masterpieces and objects of worship by the elite class were executed on the walls of temples. However, production of hanging scrolls for ritual use in the palace and aristocratic households was soon introduced, and this genre began to increase in representation.

Particularly, the court of King Uijong (r. 1146-1170) commissioned artists to produce a large number of portraits of Avalokitesvara and Indira for distribution to temples outside the capital. At the same time, pictures of the Bodhisattva of Compassion were produced in sets of 40 small pieces to be distributed to temples and individual believers in the belief that “infinite charity” would be achieved by doing so. Thanks perhaps to this craze in the mass production and distribution of small icon paintings, hanging scrolls of Gwanseeum or Jijang bodhisattvas dating to the Goryeo period are relatively plentiful today. During the subsequent Joseon period, hanging scrolls accounted for the mainstream of Buddhist paintings.

CHARACTERISTICS OF GORYEO BUDDHIST PAINTINGS

A typical Goryeo Buddhist icon painting presents the main deity as an overpowering, gigantic form. Secondary figures, such as attendants and worshippers, are almost always crowded in the bottom half of the work, below the deity’s knees. Sometimes, the halos around their heads seem to support the main deity, who is usually a buddha or bodhisattva.

It is not clear whether this particular composition existed in the Silla period, but Tang China evidently did not have a comparable tradition in its Buddhist iconography. No doubt the Joseon Buddhist painters seldom used this style.

The unique composition of Goryeo icon paintings reflects the broad gap between the powerful aristocracy and the commoners, as well as the distinction between civil and military officials and the miserable conditions of slaves. Naturally, disharmony among these classes was a source of constant struggle and revolts by the less privileged.

The Water-Moon Avalokitesvara (Detail)

The buddhas and bodhisattvas in Goryeo icon paintings are portrayed in leisurely royal poses as stately, glamorous figures with handsome faces and corpulent bodies.

Amitabha Triad (Detail)

The paintings are rendered in brilliant mineral colors, such as red, blue, and green, and finished with intricate gold outlining.

Another noteworthy feature is the tendency for the main deities to be presented as large, impressive figures in the middle of the compositions found in the frontispieces of such widely-read scriptures as The Sutra on the Meditation of Amitayas, The Avatamsaka Sutra, and The Maitreya Sutra. This style formed the basis for Joseon-era Buddhist icons.

The buddhas and bodhisattvas in Goryeo icon paintings are portrayed in leisurely royal poses as stately, glamorous figures with handsome faces and corpulent bodies. Goryeo painters did not embrace naturalism as their guide but rather took canonical descriptions for the basis of their works. Indian bodhisattvas were famous for their jewelry, and Goryeo artists obviously enjoyed decking their subjects in elaborate brooches, anklets, bracelets, arm bands, and earrings. The draperies portrayed in these works are reminiscent of the long, graceful curves of Goryeo celadon and seem to outshine even the jewelry in their richness. However, the transparency that gives the deities a mysterious sense of lightness is what makes these works truly magnificent. The paintings are rendered in brilliant mineral colors, such as red, blue, and green, and finished with intricate gold outlining.

The Goryeo artists endowed their Buddhist deities with power, grace and delicacy. Their works not only evoked religious awe and reverence in the viewer but also vividly expressed the Goryeo nobility’s refined tastes and conception of beauty.

THE SOCIO-POLITICAL FUNCTION OF BUDDHISM IN KOREA

Buddhism first came to Korea from China in 372 AD, about 800 years after the death of the historical Buddha. The new faith contributed to creating the spiritual base of the new nations and lent support to the development of strong monarchical regimes. Its impact on Korea’s socio-political culture, not to mention its spiritual culture, was enormous, especially under the Goryeo Dynasty (935-1392).

Three Kingdoms and Unified Silla

Foreign missionaries brought Buddhism to the Korean kingdoms of Goguryeo and Baekje in the late 4th century. The new faith proved an easy sell and was quickly adopted by the rulers in those kingdoms. Monks from Goguryeo and Baekje would prove instrumental in transmitting Buddhism to Japan as well.

The kingdom of Silla, did not receive Buddhism until the 5th century; however, it promoted the foreign faith and eventually declared it the state religion of the kingdom.

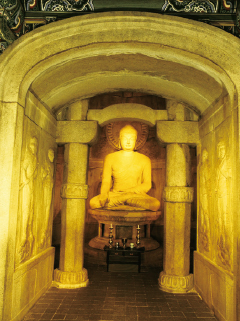

Silla went on to unify the Korean Peninsula in 668, and Buddhism—especially scholastic Buddhism—experienced a golden age. With royal patronage, temples were built all across the country: the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Bulguksa Temple and its Seokguram Grotto were built in this period. Place names for geographic features like mountains were named after Buddhist concepts. Korean monks were sent to China to study, further solidifying the cultural links between the two countries.

Seokguram Grotto, Gyeongju

Goryeo Era

It was during the Goryeo era that Buddhism reached the apogee of its social and cultural influence. Ironically, however, it was also during this period that the seeds of Buddhism’s undoing in the following Joseon Dynasty were planted.

In the political chaos of the late Silla Dynasty, when the kingdom was falling apart, Korean Buddhism witnessed the rise of a school of philosophy and practice that would become one of the faith’s dominant streams: Seon (Zen). Seon met with some resistance from the scholastic Buddhists who dominated Silla, but it was enthusiastically supported by the new kingdom of Goryeo, which took over from Silla in 935. Founded by a king, Wang Geon, who was a devout Buddhist and supported by Buddhist nobles, the kingdom made Buddhism the state religion and lavished unprecedented patronage on Buddhist temples, which were further supported with exemptions from taxation and government service. So good did the temples and monasteries have it, in fact, that before long they were amassing fortunes in wealth and property and gaining a tremendous amount of political influence.

Joseon Era

When the Goryeo Dynasty was overthrown in a military coup and replaced with the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the Confucian scholars finally seized power, making Confucianism the ruling ideology of the state. The political power of Buddhism was vanquished forever: temples in the cities were closed and the monks forced to temples and monasteries deep in the mountains, where their impact on the general population was drastically reduced. Many of the more suppressive restrictions were lifted following the Japanese invasion of Korea in the late 16th century: warrior monks played an instrumental role in the kingdom’s defense, and as a result came to be looked on more highly by the country’s rulers. Still, the religion would never come close to achieving the influence it had in the Goryeo period, and regulations—albeit less onerous ones—were kept on the religion for the duration of the dynasty.