“The flourishing of genre paintings and the growing interest in the work and leisure activities of common people in the eighteenth century reflect the changing sociopolitical climate of the second half of the Joseon dynasty. A turning point in the Korean people’s perception of their own culture and that of their neighboring countries came with the fall of China’s Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Genre painting and paintings depicting famous sites in Korea, known as jingyeong (“true-view”) landscape painting, experienced unprecedented popularity. These two painting types are frequently cited as evidence of the increasing emphasis on the development of a Korean cultural identity and are among the most celebrated artistic achievements of the late Joseon dynasty.”

Work and Leisure: Eighteenth-Century Genre Painting in Korea, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Genre paintings are widely considered the most “Korean” of the traditional Korean painting forms. This is somewhat inevitable—as candid depictions of daily life in Korea, they are visual expressions of Korea’s unique culture and social practices.

Like the move away from idealized Chinese landscapes to real Korean landscapes in landscape paintings, genre paintings grew in popularity in the latter part of the Joseon era as Korean Confucianism broke away from a stringent fidelity to Chinese practice to develop a more “national” identity.

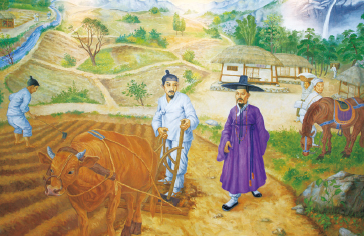

Prior to the 18th century, there had been genre paintings, to be sure. These, however, tended to be mere idealized visions of yangban life. In the 18th century, the subject shifted, as yangban artists focused their artistic attention on the lives of Korea’s common folk. Daily activities and scenes of everyday life were depicted in great detail and—in great contrast to landscape paintings—in vivid color. Few topics were taboo: some painters dabbled in erotic paintings, while others chronicled the moral corruption of the yangban class. The result was a collection of art that serves as a virtual socio-political study of life in Joseon-era Korea.

Dano. In the 18th century, the subject shifted, as yangban artists focused their artistic attention on the lives of Korea’s common folk. (Sin Yun-bok, Gansong Museum)

JOSEON-ERA GENRE PAINTING

The rise of realistic landscape painting in the mid-Joseon period was paralleled by another significant phenomenon—the popularization of genre painting. While genre painting did exist in the Three Kingdoms (57 BC-668 AD), the Unified Silla Kingdom (668-935), the Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392), and the early Joseon period, it generally depicted the insular and luxurious life of the uppermost class of society. We will use the term “genre painting” to refer to those works that began to appear in the 18th century, focusing on the everyday life of commoners. More specifically, the term refers to paintings based on such secular themes as the love affairs of gentlemen-scholars with gisaeng (professional female entertainers), merchants and farmers at work, the home life of ordinary housewives, vulgar stories that circulated among villagers, and even sexually arousing scenes.

A Wash Place. The genre painters of the late Joseon period pondered how to best portray the lives of their contemporaries, so when they created a work, it was filled with a genuine vitality that lives on in the paintings. (Kim Hong-do, 18th C, National Museum of Korea)

To portray the diversity of everyday life, a painter had to observe ordinary people with an affectionate eye as well as with a clear consciousness of himself as a commoner. This realization dawned on a few sensitive painters influenced by the Silhak Movement. These pioneers were probably able to produce fine genre paintings because they were in touch with the pulse of the land and conscious of the ethnic uniqueness of the Korean people, while at the same time remaining faithful to their basic commitment to realistic portrayal. Because their paintings were so Korean, they have transcended their narrow historical heritage to gain universal appeal today.

The genre painters of the late Joseon period pondered how to best portray the lives of their contemporaries, so when they created a work, it was filled with a genuine vitality that lives on in the paintings. During the 200-year period in which genre paintings, the most “Korean” of all Korean artistic forms, flourished, the Silhak Movement rose and spread as a innovative discipline based on a new consciousness of reality and individual identity; Western science and technology were introduced, spreading more pragmatic, realistic, and rational ways of thinking; and the awakening consciousness of the common people and introduction of Catholicism fanned a new belief in equality and a growing criticism of hierarchical Confucian society. As products of this transitional period, it is no wonder genre painters candidly depicted the lives of ordinary Koreans.

The realistic landscape and genre paintings of the mid-Joseon era reflect the changing nature of that society and its people. When seen from the broader perspective of Joseon-era painting as a whole, the transformation in style represented in these works is nothing less than revolutionary. It was through these works that painters were able to express their uniquely Korean thoughts and sentiments.

LEADING ARTISTS

The genre paintings of Joseon period surge with a vitality born of the spirit of their times and the lives of the common people. But who created these remarkable works so rich in dignity and poetic sensibility?

The period from the early 18th century to the early 20th century saw the rise of the Silhak Movement in Korean language literature, and realistic landscape and genre paintings. It was a time of cultural renaissance, of national enlightenment and an awakening of the Korean identity.

Kim Hong-do (1745-?)

The best genre paintings of the Joseon period are indisputably the masterpieces left behind by Kim Hong-do. A master at all kinds of painting, Kim’s creativity, originality, and personality are revealed in the themes, composition and style of his genre paintings as in all his other works. The National Museum has a large collection of Kim’s genre paintings, and every one is a masterpiece. The themes are varied: roof-tiling barmaids; washing clothes at a well; mat making; a village school; a blacksmith’s forge; a wedding procession. None of these masterpieces could have been produced if the painter were not endowed with great imaginative powers, a fervent love for ordinary people, and superb painting skills.

Pyeongsaengdo. This work reveals Kim’s belief that paintings were an important form of historical record. (Kim Hong-do, 18th C, National Museum of Korea)

DANWON GENRE PAINTING ALBUM

The genre painting album of “Danwon” Kim Hong-do consists of a total of 25 pieces. These works present a vivid window into the lives of people in old Korea, with renderings of old marriage customs—a gireok abi (goose holder) holding a goose for the mother of the bride, the groom’s nursemaid following the ceremonial procession—and a variety of other subject matter, including the tilling of fields, archery, peddlers, dancing children, a smithy, the admiration of artwork, and a marketplace.

The appeal of Kim’s genre paintings lies in their effective composition, which focuses the gaze on one location, and in their compact and powerful lines. Kim principally strove to depict the amusements and customs he found in popular life, and he preferred to omit backgrounds, painting only the postures and movements of the figures within the painting.

Ssireumdo from Genre Painting Album. (National Museum of Art)

Kim also produced a large number of biographical series (pyeongsaengdo) and ajipdo, paintings of gatherings of gentlemen, which reveal his belief that paintings were an important form of historical record. Kim probably produced these types of paintings upon request; however, his other genre paintings must have been done of his own volition. They are full of life and refreshing appeal because Kim painted them from the common life he loved so much to observe. He also left an album of genre paintings in which the human figures seem very much alive. His favorite subjects were traditional games, shoe making, and outdoor recreation scenes.

Sin Yun-bok (1758-?)

When it comes to colorful genre paintings with a distinct hint of sensuality, no one can beat Sin Yun-bok. Although they both lived in Seoul, Sin’s artistic world was quite different from that of Kim Hong-do, who was 13 years his senior. The two share little in the way of motifs, composition, the portrayal of human figures, color, or atmosphere. In a word, Sin’s work is almost too romantic and erotic. His best works depict tavern scenes, shamans, sword dances, spring outings, women bathing on Dano (the fifth day of the fifth lunar month), gisaeng houses, and lovers in the moonlight. Sin’s paintings always manage to arouse curious feelings in the viewer.

Yun Du-seo (1668-1715)

Yun Du-seo left the best self-portrait by a Joseon-era painter. Great grandson of Yun Seon-do (1587-1671), an eminent poet who wrote many excellent Korean-language poems including “The Fisherman’s Calendar,” Yun Du-seo was well-versed not only in painting but also in Confucianism, military strategy, astronomy, geography, medicine, and music. He was a skilled painter of landscapes, portraits, and animals, and as a pioneer in genre painting he loved to deal with motifs from the daily life of commoners, such as women collecting wild greens and craftsmen at work.

(Text in top left) “The spring in her heart and turmoil in her mind Are captured well by my paintbrush.”

The Beauty (Sin Yun-bok, 18th C, Gansong Museum)

Yun Deok-hui (1685-1775)

A son of Yun Du-seo, Yun Deok-hui was also a fine landscape, portrait, and animal painter following his father’s style. One of his most representative works depicts three children playing jacks, while another portrays a groom with a horse under a tree. Yun Du-seo’s grandson, Yun Yong, was also a professional painter. His works include paintings of scholars and women collecting mugwort.

Jo Yeong-seok (1686-1761)

Jo Yeong-Seok’s work is generally more accurate and serious than that of the three Yuns. He left a fairly large number of works on diverse themes—fishing boats, soldiers riding boats, a stable with horses, men cooling themselves under a tree on a hot summer day, traditional games, women sewing, etc. Of particular note is Jo’s painting of farmers taking their midday meal in the fields, a work quite similar to a painting by Park Soo-keun (1914-1965), a contemporary painter whose favorite motif was the commoners’ everyday lives. These two painters succeeded in depicting a true image of the Korean people, an image that transcends time and place. Jo left several literati paintings as well as many genre paintings. The most representative of his works extant today are: Viewing the Waterfall, An Ox Left Out in a Snow-covered Field, An Old Tree, Fishing on the River, and Cooling Oneself under a Willow Tree.

Kim Du-ryang (1696-1763)

Although he was a good landscape and portrait painter, Kim Du-ryang deserves our attention as a top-notch genre painter. His talent in this field is best demonstrated by his work depicting a shepherd boy taking a nap and a painting portraying rural village life throughout the four seasons. Kim’s genre paintings, set against a backdrop of scenic mountains and streams, are also interesting because they reveal not only the influences of the Chinese Zhe School but also Western painting styles. His paintings of farm laborers influenced the work of Kim Hong-do and Kim Deok-sin.

Fishing Boat. Jo Yeong-Seok’s work is generally more accurate and serious than that of the others in his era. (Jo Yeong-seok, 18th C, National Museum of Korea)

THE SOCIO-POLITICAL FUNCTION OF CONFUCIANISM

The key to promoting Neo-Confucian philosophy was the all-important civil service exam, or gwageo.

In Korea, Confucianism is most strongly identified with the kingdom of Joseon (1392-1910), when the philosophy was adopted as the supreme ideology of the land. The 1392 coup that brought the Yi family to power, giving birth to the Joseon Dynasty, marked the ascendancy of Confucianism from one of several coexisting philosophies in previous dynasties to the dominant philosophy of the land. Korea’s new rulers did not view Confucianism as simply an administrative tool; rather, they sought to completely transform society on Confucian principles. The influence of Buddhism—hitherto the dominant national philosophy—was severely curtailed, and Confucian ideals such as loyalty and filial piety were promoted. Korean society was dominated by a class of literati, or yangban, whose social standing was due in large part to their knowledge and mastery of the Confucian classics.

It should be noted that the Confucianism that took root in the Joseon era was not the “classical” Confucianism but rather so-called “Neo-Confucianism,” a form of Confucianism that developed in the Song and Ming Dynasties of China. In Korea, Neo-Confucianism was promoted and transmitted through a system of Confucian schools and academies—some run by the state, others established by famous scholars—that hosted scholars, ran libraries, and patronized the arts and culture. The real key to promoting neo-Confucian philosophy, however, was the all-important civil service exam, or gwageo. This exam, an absolute requirement for anyone wishing to secure political office (the principal road to wealth and power in Joseon society), tested takers’ knowledge of the Chinese classics and Neo-Confucian thought.

Korean Confucianism reached its intellectual peak in the 16th century, when Korea was blessed with its two greatest Confucian scholars, Yi Hwang (1501-1570) and Yi I (1536-1584). The former was a “scholar’s scholar,” a man who preferred the rigors of academic life to those of politics, which he engaged in with only the utmost reluctance. The latter was an energetic reformer who served in a number of high government posts. The faces of both can be found on Korean banknotes, an indication of the high regard in which the men are held even today. The 17th century, meanwhile, witnessed the rise of an important movement within Korean Confucianism, Silhak (Practical Learning). As the name would suggest, this movement focused on using Confucianism to make improvements in the actual lives of the people, and is closely associated with the promotion of science and technology during the era.

Painting by Joseon-era Silhak practitioner Kim Yuk (1580-1658), Silhak Museum