Of the Korean portrait paintings extant today, the oldest date back to the Three Kingdoms period. Figure paintings, primarily of couples, have been found on murals in Goguryeo tombs, and evidence shows that portrait paintings were produced throughout the Unified Silla (668-935) and Goryeo (918-1392) periods. The demand for portraits for ceremonial use increased sharply during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) when Confucianism was adopted as the guiding ideology, and numerous ceremonies were observed in an effort to encourage filial piety and promote a respect for wisdom among the Korean people. As a result, there was a great demand for portraits of a variety of subjects.

Traditional portrait paintings can be classified into six general categories based on the social status of the subject: portraits of kings, of meritorious subjects, of elderly officials, of literati, of women, and of Buddhist monks.

It is not dear when the first portraits of kings were painted. However, Samguk Sagi (The History of the Three Kingdoms, written by the Goryeo scholar Kim Bu-sik in 1145) mentions royal portraits on the walls of Buddhist temples during the Unified Silla period. The Goryeo court had a pavilion in which the portraits of its kings were enshrined, and portraits of queens were also actively promoted. However, only two royal portraits from the Goryeo period remain today: a sketchy painting of the Goryeo founder Taejo (r. 918-943) and one of King Gongmin (r. 1351-1374) and his Mongolian wife, Princess Noguk, which is now kept in a pavilion at the Joseon royal ancestral shrine in Seoul.

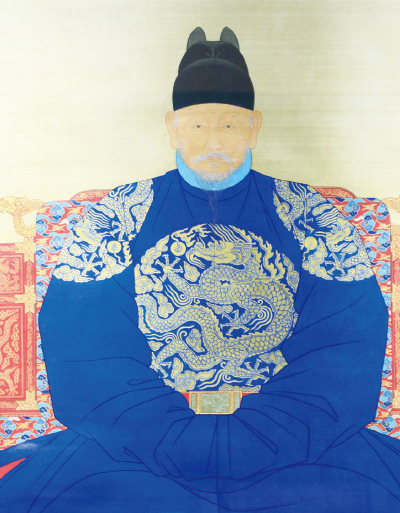

Portrait of King Taejo. Yi Seong-gye, the founding monarch also known as Taejo, was the subject of 26 portraits. This one was designated National Treasure No. 931. (1410, Gyeongbokgung Palace)

Portrait of King Gongmin and Princess Nogukdaejang (Gyeonggi Provincial Museum)

A vast number of portraits were produced for the 27 kings of the Joseon period. Yi Seong-gye, the founding monarch also known as Taejo, was the subject of 26 portraits, and a new portrait of Yeongjo (r. 1724-1776), the 21st ruler, was commissioned every ten years.

Few of these royal portraits, or eojin, remain today, however. In fact, the only surviving portrait of Taejo is a reproduction dating to 1892, although it appears to be a faithful copy of the original work, a full-length portrait of the founding monarch dressed in a formal robe and crown with his hands folded. A half-length portrait of Yeongjo, housed in Seoul’s Changdeokgung Palace, depicts the monarch’s face and provides a clear portrayal of his personal character. Originally housed in a shrine for his mother, this portrait is relatively small compared to other Joseon-era royal portraits, which generally presented a full-length frontal view of a dignified king standing as if he were addressing an audience of his retainers.

Seungjeongwon Ilgi (The Diary of the Royal Secretariat), a Joseon era document, includes an account of the procedures used in the production of royal portraits. First, a temporary office was established to supervise the work. Artists were then selected through examination or recommendation. Rough drafts were made, and then the actual portrait was painted in ink on the silk canvas. Next came the coloring, mounting, affixing of a title, enshrining, and finally citation of the artists and ministers in charge. Divination was used to determine auspicious days for each of these processes, and the king and his ministers often examined the painting in progress.

In fact, the production of these royal portraits was tantamount to a major state event, since the paintings symbolized the authority of kings and their aspirations for the perpetuation of the dynasty. Therefore, each royal painting was produced with great care and effort.

PORTRAITS OF MERITORIOUS SUBJECTS

The title “meritorious subject,” or gongsin, was bestowed as an expression of appreciation by the king on those who performed distinguished services for the state. The king usually ordered the painting of the portraits of those awarded this status, a great honor not only for the gongsin themselves but also for their families for generations to come. The system served to enhance the power and prestige of the monarchy and warn citizens against disobeying their monarch.

The system of bestowing gongsin status on loyal servants is believed to have originated in Han China (202 BC-AD 220), but the earliest record of this practice in Korea dates to 940, when Goryeo’s Taejo ordered the construction of a shrine at Sinheungsa Temple to honor those subjects who had served in the founding of the new dynasty. This shrine, called Gongsindang, or the “hall of meritorious subjects,” housed the portraits of meritorious subjects honored by their king for their roles in expelling foreign invaders, controlling internal revolts, and other acts of national significance. Regrettably, none of these portraits remain today.

In the Joseon Kingdom, no fewer than 28 different titles were used to commend the so-called “meritorious subjects.” It was not uncommon for 100 or more retainers to be granted titles at one time. Such massive commendations were accompanied by an equally massive boom in portrait painting. Leading artists were usually mobilized for the task at the order of the king.

In almost all cases, the subject would sit in a chair with his hands folded in front of him. Dressed in his official robes and black silk hats, the subject wore his official emblem on his chest. These chest patches serve as important materials for historical research, as they reveal the subject’s rank in the government at the time of the painting. As time passed, this style of portrait grew popular among the Joseon elite, and many aristocrats, even those without gongsin status, had their portraits painted in similar poses.

PORTRAITS OF ELDERLY OFFICIALS

While fewer in number, girodo, or portraits of elderly officials, are considered as important as those of meritorious subjects because they were a means of memorializing the subject. The word giro refers to elderly men in their sixties or seventies, but it took much more than age for a man to qualify for one of these portraits. He had to hold a respectable social position and be known for his virtuous character and other personal attributes.

Societies of elderly men were common in China during the Tang and Song Dynasties. In Korea, aristocratic men of letters formed fraternal societies during the Goryeo period. A court agency, known as the Giroso, replaced these private gatherings in 1394, shortly after the founding the Joseon dynasty. Even Taejo, the founding monarch, joined the agency when he turned 60. Civil officials over seventy of the minor second rank (jong-i pum) or above were given membership in the agency on a selective basis. The agency existed through the end of the dynasty, but it was never more than symbolic in authority and had little actual power. Nevertheless, it was a great honor for civil officials of advanced age to be a member.

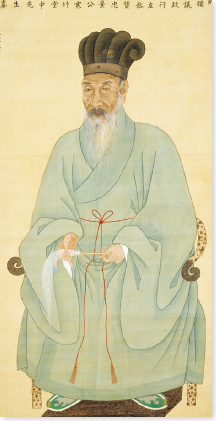

Portrait of Sin Im. Portraits of elderly officials are considered as important as those of meritorious subjects because they were a means of memorializing the subject. (18th C, National Museum of Korea)

Most of the portraits of elderly officials extant today are album leaves, much like modern-day school albums. However, some folding screens and hanging scrolls do exist. One folding screen depicts Gweon Dae-un and seven other newly initiated members of the Giroso in 1689. The officials are shown against the background of a Chinese-style mansion and garden.

Also worthy of special mention are two 18th century pieces executed by a group of leading portrait painters, including Jang Ok and Jang Gyeong-ju. One of these album leaves dates to 1719, and the other was painted in 1744. Both contain small, half-length portraits of figures with stereotyped features and postures. The coloring was done in layers, a common Joseon-era technique, which made the faces appear more realistic.

Larger individual portraits were also produced privately.

Portrait of Yi Jae. A portrait of late Joseon-era scholar Yi Jae (1745-1820) is typical of the portraits of Joseon literati. (1803, National Museum of Korea)

Self-Portrait. Yun’s self-portrait is impressive for its shrewd depiction of a handsome face with a penetrating gaze and impressive side whiskers and beard. (Yun Du-seo, 1710, Nokudang, Jeollanam-do)

PORTRAITS OF THE LITERATI

Portraits of the literati, or sadaebu, as the scholar-officials were called, were the most common form of portrait. Many of these full-length paintings provide a highly successful portrayal of their subjects. This is probably because the painters had more frequent contact with their subjects in a relaxed atmosphere. However, the quality of these portraits varies widely, while those of meritorious subjects tend to maintain a certain standard of quality, although they can be quite stereotyped.

Historical records, as well as the few extant examples of literati portraits, indicate that such paintings were first produced during the Unified Silla period. The Goryeo period saw the active production of portraits of the learned nobility, and demands for such paintings began to increase drastically during the Joseon period, when Confucian social decorum required numerous ceremonies at ancestral shrines, private academies, and public educational institutions. Portraits of ancestors or revered ancient sages were housed at all such sites.

In this respect, the literati portrait genre played a unique role in the development of Korea’s portrait painting and was quite different from portrait painting in China or Japan. For example, in most portraits of Chinese scholars produced in the late Ming and Qing periods the figures were portrayed with simple, abbreviated strokes. These pictures were usually presented in handscrolls or album leaves since they were, for the most part, created for aesthetic appreciation. In Japan, the portrait genre focused on emperors, monks, and shoguns, and portraits of literati were relatively unpopular until recent times.

Portraits of Korean literati were usually produced in impressive sizes, 180 x l00 cm or larger, for ceremonial use. Most often the subject was shown sitting cross-legged, wearing elegant scholar’s robes called simui or hakchangui. In some cases, the subject was seated on a chair, wearing his official uniform much like the meritorious officials.

A portrait of late Joseon-era scholar Yi Jae (1745-1820), painted in 1803, now on display at the National Museum, is typical of the portraits of Joseon literati. It is a half-length painting of Yi wearing a Confucian scholar’s robe and hat. There is a pleasant contrast of black and white, and the multilayered coloring along contour lines gives the face a three-dimensional effect. Complimentary remarks written in blank spaces, including one inscription by the master calligrapher Yi Gwang-sa, add to the flavor of the portrait.

Self-portraits developed as a distinct portrait genre in the Orient from ancient times, but, unlike their European counterparts, such as Dürer, Rembrandt, or Van Gogh, few artists ever achieved much of a reputation for their genius or individuality in this field. In China, the scholar official Zhao Qi is said to have painted a portrait of himself and a friend on the wall of his tomb during the Ran period. The earliest record of a Korean self-portrait is that of King Gongmin in 14th century Goryeo. Gongmin is said to have painted from a reflection in a mirror. During the Joseon period, literati painters Kim Si-seup (1435-1493), Yun Du-seo (1668-1715), and Gang Se-hwang (1713-1791) all left self-portraits of themselves. Yun’s self-portrait is particularly impressive for its shrewd depiction of a handsome face with a penetrating gaze and impressive side whiskers and beard.

PORTRAITS OF WOMEN

Portraits of women are the least conspicuous category of Korean portrait painting. The earliest evidence of such portraits was found in the murals of Goguryeo tombs, such as Tomb No. 3 in Anak, the Tomb of the Four Deities (Sasinchong) in Maesalli, and the Tom bof the Twin Pillars (Ssangyongchong). The faces of the women depicted in all these wall paintings are unrealistic and stylized. The women are all accompanied by men who appear to be their husbands. There are no records of women’s portraits from the Unified Silla period. During the Goryeo period, portraits of queens are said to have been produced along with those of king, but none remain today.

During the early Joseon period, portraits of queens were painted together with those of the kings and enshrined in a hall for royal ancestral portraits. However, there is no record of the production of portraits of queens after the Japanese invasions of 1592-1598. In fact, in August 1694 King Sukjong ordered a literati painter, Kim Jin-gyu, to paint a portrait of his wife, Queen Min, but he was severely chastised by his ministers as well as Kim himself. The Confucian ethical code forbade the company of males and females over the age of seven, so it was unthinkable for a queen to sit for a male painter. Sukjong eventually withdrew his instruction, and no portraits of queens were produced thereafter.

Portrait of Sin Saimdang. Sin Saimdang, a writer and calligrapher, is featured on the 50,000-won bill. This is the first time a woman’s portrait has appeared on a bill in South Korea.

In the early Joseon period, there seems to have been a popular trend among the literati to commission portraits of husbands and wives together. Among the extant examples of this genre are paintings of Bak Yeon, a music scholar in the court of King Sejong (r. 1418-1450), and his wife, and of Ho Yeon and his wife. Both portraits were restored after the original colors faded. Regrettably, no other portraits of literati couples are known to have been painted after the mid-Joseon period.

PORTRAITS OF BUDDHIST MONKS

It is easy to assume that portraits of Buddhist monks would have preceded the development of portraits of people from other walks of life. However, historical documents and inscriptions on monuments from the Unified Silla period do not contain any specific references to this genre.

During the Goryeo period, portraits of Buddhist monks were a common artistic form thanks to the growing popularity of Zen Buddhism, which emphasized the guidance of teachers rather than the worship of specific buddhas or bodhisattvas in the attainment of enlightenment. Portraits of revered priests were produced and enshrined in temples across the country. Complimentary salutations found on these portraits are included in various literary anthologies. Of particular note among the Goryeo portraits of high priests extant today are those of Bojo (1158-1210) and Jingak (1178-1234) both enshrined in the Guksadang, or the Hall of National Preceptors, at Songgwangsa Temple. However, both works have lost much of their original value because of excessive restoration.

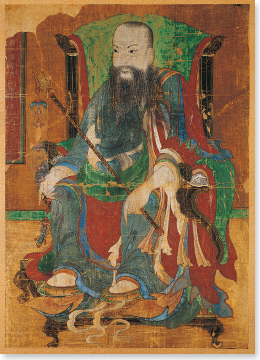

Portraits of Buddhist monks continued to be produced during the Joseon period, although the Confucian rulers suppressed Buddhism. Many of the Joseon-era paintings are now preserved in the Josadang, Halls for High Priests, or found at many temples. These paintings are divided into two general groups depending on the subject’s pose. In the first style, typified by the portraits of high priests Hakjo and Muhak (1327-1405), the subject is portrayed full-length, seated in a chair as was the custom from the late Goryeo period. The subject is seen from the side in a three-quarter view, holding a staff in one hand and gripping the arm of his chair with the other. His feet are elevated on a low stool. The second type of monk portrait is exemplified by the paintings of the renowned priests Seosan (1520-1604) and Jaewol. The subject is also seen from a three-quarter view at full length, but he is seated on a cushion and holds a staff in his left hand. The right hand either holds a rosary or rests on the subject’s knee. Few portraits of Buddhist monks have been preserved in their original state. Repeated restoration and copying have been necessary because of smoke damage from the incense and candles burned in Buddhist shrines and because of constant exposure to worshippers. These portraits also suffer stylistically because they were generally produced in mountain temples secluded from the outside world and so did not benefit from developments in poses, background, or brushwork and coloring techniques. Nevertheless, fine portraits do exist; for example, a portrait of the famous priest Samyeong Daesa (1544-1610), which is kept at Donghwasa Temple in Taegu, powerfully portrays the subject’s lofty spirit.

Portrait of Samyeongdaesa. A portrait of the famous priest Samyeong Daesa (1544-1610) powerfully portrays the subject’s lofty spirit. (16th C, Dongguk University Museum)

THE SOUL LURKS IN THE EYES

Most traditional portraits were painted by professional artists because skillful brushwork was considered a prerequisite for a realistic depiction of the subject. In other words, verisimilitude was regarded as the key element in the Korean tradition of portrait painting. Painters always worked with the conviction that even the most insignificant strand of hair must be painted correctly.

No less important from the standpoint of the viewer, however, was the question of whether the soul or spirit of the subject was faithfully represented. Therefore, artists always strived to locate the subject’s soul. The most authoritative theory on this subject was that the soul lurked in the eyes. A discussion of the elaborate procedures surrounding the painting of a royal portrait recorded in The Diary of the Royal Secretariat from the Joseon period states that the king’s eyes were painted by the supervising artist in a solemn court ceremony observed at a date and time determined to be most auspicious by court fortune-tellers. The king and his ministers attended the ceremony to observe the painting of the eyes.

This theory could not be applied to all subjects, however. Sometimes, the strategic point where the soul was located could be the eyebrows, the nose, the mouth, the cheekbones, or even the whole face. Therefore, the artist always had to scrutinize his subject carefully, using intuition to determine where the individual’s soul lay.

An episode involving Gang Se-hwang (1712-1791), a master painter in 18th century Joseon, reveals how important a brushstroke or two could be in this regard. Gang painted a self-portrait but was dissatisfied with the result. It was only when his friend Im Hui-su, another prominent painter, added a few brushstrokes along the lower edge of the cheekbones that Gang felt his soul had been correctly portrayed. Similarly, a portrait of Song Si-yeol (1607-1689), a famous Confucian scholar and statesman of 17th century Joseon, depicts an old man holding his shoulders awkwardly with his neck drawn back and face thrust forward. The painting may have little aesthetic appeal, but it vividly depicts the man’s spirit and tenacity.

PERFORMING THE FUNCTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY

The Joseon people would place portraits on the ancestral shrine when carrying out the Confucian custom of the jesa (ancestral rites).

Portraiture developed into a very important area in East Asia. It first appeared on the Korean Peninsula in the tomb murals of Goguryeo and enjoyed great popularity through the Goryeo era and into the Joseon era, which saw the painting of a great many portraits. The reason portrait painting flourished in Joseon was because of the influence of Confucianism, which placed emphasis on loyalty (chung) and filial piety (hyo).

The Joseon people would place portraits and wipae (small tokens bearing the name and post of an ancestor) on the ancestral shrine when carrying out the Confucian custom of the jesa (ancestral rites). At such times, a portrait performed much the same function as a photograph would today.

Because it was thought that Korean portraits had to be perfect likenesses of the subject, right down to the smallest whisker, painters dedicated their energies to producing exact representations. Also, jeonsinsajo—the dictate that a painting not simply be a recreation of the individual’s features but also capture that person’s soul—was seen as the paramount value in portraiture. This means that in addition to a subject’s outward appearance, his or her unique internal essence was also seen an important feature of the representation. Most of the portraits that have survived to the present are from the late Joseon era onward.

Portrait of Song Si-yeol. Song Si-yeol (1607-1689), a famous Confucian scholar and statesman of 17th century Joseon, depicts an old man holding his shoulders awkwardly. (17th C, National Museum of Korea)

Korean portrait painters did not limit their interests to the individual characteristics of their subjects, however. They also studied physiography to better understand the general features of the human body. At the same time, they attempted to understand the social background, profession, and personal character of their subjects, as the portraits were intended to present them in the best possible light. The portraits were designed to evoke in the viewer both positive memories and deep reverence for the subject. The British scholar Arthur Waley (1889-1966) aptly coined the expression “biography + imagery” to describe this aspect of Oriental portrait painting.

It was only natural, therefore, that the portraits of kings were meant to symbolize the supreme authority of the dynasty. Painters did their best to portray a majestic image of their ruler in audience with his loyal subjects. Meritorious subjects were most often portrayed as the embodiment of nobility and dignity, models for their descendants, and paintings of literati emphasized the subject’s intellectual character.

This tendency to portray idealized traits in addition to the physical characteristics or personality of the subject enhanced the value of the portrait as a historical testimonial. The portrait painter did not regard the physical appearance of his subject simply as a form for artistic expression, nor did the viewer seek only aesthetic enjoyment in these paintings. Rather, both the painter and the viewer saw these paintings as an expression of the unique character of the subject and his or her times.

Thus, when a king took refuge during a war, portraits of his royal predecessors were always taken along. The king and his ministers observed rites to appease the deceased kings’ souls and seek their assistance in overcoming the crisis. Commoners also carried spirit tablets and portraits of their ancestors with them when they fled during times of war. If it was impossible to carry these items with them, they would place them in a large jar and bury them in a safe place. Few people took these precautions with genre or landscape paintings. However, thanks to the Korean people’s reverence of their ancestors, more than 1,000 traditional portraits have survived in the hands of private citizens and museums around Korea to provide us with works unique for their artistic value as well as historical significance.