By late 1916 Dublin Corporation had reverted to type, operating in an atmosphere in which members conducted business as they had always done, collegiality giving way to sudden storms over appointments to committees or the filling of vacant posts. The battles over who should be given a job as rate-collector or technical school instructor could often assume Homeric proportions. However, some new trends were proving irreversible, such as the dwindling support for the war and increasing antagonism towards the British authorities.

The fall-out from the death of Francis Sheehy Skeffington and other civilians, delays in the payment of compensation to owners of property destroyed in the rising and the treatment of rebel prisoners—there were city councillors in both categories—fuelled the realignment of loyalties. By contrast, there was little engagement with events on the western front, let alone in the Balkans and Middle East, except for those citizens with relations in the armed forces. As the great majority of the recruits now came from the poorest and least influential elements of the population, their opinions went largely unheeded.

Even the start of the Somme offensive on 1 July 1916 attracted relatively little attention. Never again would Dublin suffer the sort of communal shock inflicted by the news of the Dardanelles casualties a year earlier. Undeterred by recent events at home, the Irish Times hailed the gains claimed by the British high command in the opening days of the offensive as ‘a new and glorious chapter to Irish history,’ giving prominent coverage to the achievements of the 36th (Ulster) Division. ‘Her young soldiers have now earned their place beside the veteran Dublins and Munsters and Inniskillings [Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers] who went through the hottest furnace of war at Helles,’ the Times enthused. While it conceded that the ‘blood of Irishmen shed by Irishmen is hardly dry on the streets of Dublin … out there in the forefront of Ireland’s and the Empire’s battle the men of all our parties, all our creeds, all our social classes, are fighting side by side.’ It predicted that ‘no political hates or passions can survive that brotherhood of action.’

However, the activities of the 16th (Irish) Division, which also participated in the offensive, received little publicity, which further alienated nationalist opinion and diluted nationalist identification with the events in France. The offensive coincided with the publication of the report of the Royal Commission on the Rebellion in Ireland. This was highly critical of the Irish administration and in particular of the former Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell. It also gave rise to renewed calls for a public inquiry into the murder of Francis Sheehy Skeffington and other civilians during the rising.

Most damaging of all were John Redmond’s concessions to Lloyd George on partition, which were to be debated in the House of Commons that week. While the Irish Times celebrated the ‘brotherhood of action’ on the Somme, the Irish Independent denounced Redmond and the United Irish League for ‘surrendering’ the fortress of home rule, contrasting their lack of parliamentary effectiveness with Carson’s resolve.

Meanwhile Dublin began to receive a new influx of wounded. These men were largely convalescent cases, shipped from hospitals in France to make way for fresh battlefield casualties. They would bring no new stories from the Somme front that might have provided some sense of immediacy and national involvement with the newspaper headlines. For most politically aware Dubliners still at liberty the continuing health and housing problems in the city, illustrated by the Baby Week conference in the Mansion House, were more pressing than the question of how many yards were won in Flanders. Otherwise any sign of returning normality was welcomed, and the news that most impressed itself at the end of the week in which the Battle of the Somme began was that Clery’s department store had reopened in temporary premises at the Metropolitan Hall in Lower Abbey Street.1

Military recruitment in Dublin virtually dried up in the aftermath of the rising. Although it revived somewhat in the summer, the total fell to 4,292 for the year, less than half the 9,612 who volunteered in 1915 and significantly less than the 7,283 who joined in the last five months of 1914. The latter figure, of course, was somewhat inflated by the recall of reservists.

Reports of hostility towards the military presence grew in the months after the rising. When the honorary colonel of the Irish Guards, Field-Marshal Kitchener, died en route to Russia, John Dillon noted in a letter to T. P. O’Connor that Dubliners ‘cheered for the Kaiser and for “the torpedo that sank Kitchener”.’2 By the autumn, people were appearing regularly in the Dublin police courts for assaults on soldiers, usually the result of casual altercations in the street. When a private from the 5th Lancers was knocked down in a fight with a civilian in Wexford Street in early October, onlookers kicked him on the ground; and a military policeman escorting a drunken soldier had to be rescued from a mob by the DMP.3

The subscription lists for food, clothing and other aid sent to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers who were prisoners of war in Germany were almost exclusively filled by leading figures of the unionist establishment in the city. Where there were donations from groups of workers they tended to be employees of such companies as Guinness, John Jameson and Son, the Great Southern and Western Railway and the Royal Bank, whose boards of directors were dominated by unionists.4

Members of Dublin Corporation showed more concern for the conditions in which men interned after the rising were being kept at Fron Goch prison camp in Wales than for members of the ‘Dublins’ in German prison camps. Alfie Byrne, who was proving a reliable weathervane of popular sentiment, was far more vocal in calling on an American delegation visiting prisoner-of-war camps for German soldiers in Britain to add Irish rebel prisoners to their itinerary than in expressing concern about the conditions in which Irish prisoners of war were being kept in Germany. However, Byrne, who believed all politics were local, also called for separation women in Dublin to be paid the same cost-of-living allowance as their London sisters. This was passed without a vote, no doubt because the cost would be borne by the British exchequer.

It was only in 1917 that the corporation decided to set up a committee to assist invalided veterans and dependants found to be ‘badly in need of assistance’ in the city. The committee’s main activity appeared to be lobbying the Local Government Board for funds rather than raising money itself.5

Unionist councillors were outraged by Byrne’s concern for rebel prisoners in Britain; but there was a growing sense of impotence in their ranks. ‘Volunteer’, an anonymous letter-writer to the Irish Times, articulated the loyalist response to the shifting political environment. After criticising Redmond for expressing himself satisfied with the rate of recruitment to the British army, he added: ‘Not only are the loyal Irish ashamed of Irish politicians but hundreds of thousands of Britishers and Colonials are beginning to look on Ireland and the Irish with contempt and disgust.’Young English men recruited to Irish regiments were arriving on Irish soil only to encounter hostility from civilians happy to have the ‘bloody and brutal Saxon’ fight Ireland’s battles abroad.

By contrast, Father Michael Curran, private secretary to Archbishop Walsh, told a sodality meeting in October 1916 that ‘those elected to represent them in Parliament have sold them.’ While he did not yet disown his own belief in constitutional politics, he had no faith in the way it had been conducted in recent years. ‘The great question at the present moment is not Home Rule, but the right to preserve our young men in this country, which has been so depopulated [by the war].’ It is unlikely that Curran would have made such a public statement without the sanction, if not the prompting, of Dr Walsh.

Perhaps even more telling was a letter in the Irish Independent from Sergeant R. Walsh of the Royal Irish Rifles, home on leave, who expressed his disgust after attending a rally in Waterford where he saw ‘strapping fellows of respectable appearance pummelling and beating young girls, even if the girls were in the wrong,’ for heckling Redmond as he sought to simultaneously condemn the British government’s reaction to the rising and urge continuing support for the war. Sergeant Walsh added that there was plenty of fighting in Flanders for those who wanted it.6

The daily ‘roll of honour’ in the newspapers and the steady stream of casualties arriving on the hospital ships provided cogent reasons why many hesitated to volunteer, whatever their political convictions. By the end of 1916 the volume of casualties disembarking in Dublin led to sheltered gangways being built so that the wounded, and especially those who had to be brought off on stretchers, could be carried directly from the hospital ships to the ambulances without being exposed to winter weather.7

By early 1917 another problem threatening to overwhelm the medical services was the spread of consumption (TB) in the trenches. It was a health problem with which Dublin was very familiar. Although the rate of infection had fallen gradually over the previous decade, because of initiatives by Sir Charles Cameron and Lady Aberdeen’s Women’s National Health Association, it still accounted for 1,300 deaths a year in the city. Now the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Help Society appealed for assistance with men being discharged with TB, much of it the result of gas poisoning. Of 1,100 disabled soldiers and sailors on the society’s books in Dublin in February 1917, fewer than half had been found employment, and 114 of the 600 unable to find work had TB. The honorary secretary of the society, Miss P. A. White, told the Irish Times: ‘That there should be a want of means to carry on this work effectively and render less intolerable the shortened lives of those who have fought for us cannot, I am sure, be the wish of their fellow countrymen.’ One suspects that the appeal struck a chill chord among potential recruits.8

Her experience is borne out by research into First World War dead at Glasnevin Cemetery by Shane Mac Thomáis. This shows that more than half of those whose records he examined died of respiratory diseases, mainly TB and influenza, compared with fewer than one-twentieth as a result of battlefield wounds. Of course these were men who made it home to die. Like the growing number of maimed veterans who survived, they offered a warning of their possible fate to would-be recruits.9

Growing suspicion of the loyalty of Irish units by the military establishment must have had an even more insidious effect on recruitment. The poet Francis Ledwidge, who enlisted in 1914, told his brother that he didn’t want to fight the Germans any more, even if they came into his back yard. There were increasing reports of weapons and other equipment going missing. According to F. E. Whitton, historian of the Leinster Regiment, on 4 November 1917 the Irish Volunteers brought a barge up the Grand Canal to the rear of Wellington Barracks (later Griffith Barracks, now Griffith College) on the South Circular Road, and ‘every rifle’ was handed through the railings and loaded onto the vessel. While this is certainly an exaggeration, the consequences were that ‘the command decided they couldn’t trust the Irish regiments. They brought over an English regiment to replace each Irish unit and we were put back on the boats that they came over on.’10

Another reason why recruitment failed to revive after 1916 was the increasing range of employment opportunities in England. Conscription had stripped vital war industries of manpower, and the shortage was so great that in September the Army Council issued a circular that migrant workers employed in those industries would be exempt from conscription. As an added safeguard, any Irish worker who obtained a job through the labour exchange system would receive a card that would be accepted as evidence by the police and military authorities that they normally resided in Ireland. The only condition was that any man losing his job must return home. Even if other work was available he would have to reapply through his labour exchange in Ireland to retain protection from conscription.

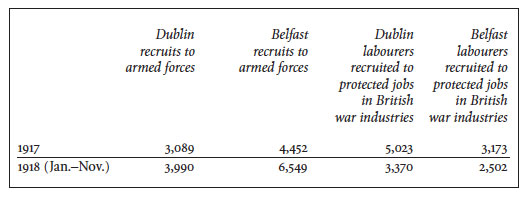

Table 7

Recruitment to British armed forces and war industries after Irish labourers given protection from conscription

Even so, rumours abounded that ‘hundreds of men’ were being arrested. At Alfie Byrne’s insistence, the corporation made ‘an emphatic protest’ to the British government at these alleged breaches of the guarantee that excluded Irish workers from the Military Service Act.11 Some migrant workers returned anyway because of the public hostility they encountered after the rising, especially Dubliners in Liverpool and seasonal workers in Scotland.12

Neil O’Flanagan suggests, from an examination of labour exchange records, that between forty and fifty thousand workers, the great majority of them men, migrated to Britain for work. In December 1916, by which time the scheme providing protection from conscription was in full swing, Dublin labour exchanges were providing 30 per cent of total Irish manpower to the British war economy. In 1917 the city provided 5,023 out of 19,551 Irish workers, or 26 per cent; in 1918 it provided 3,370 out of 14,656, or 23 per cent. By contrast, there were 3,089 enlistments in 1917 and 3,990 in 1918. The increase in recruitment in 1918 is probably attributable in part to declining opportunities for war work but also to the potential new employment opportunities available to men enlisting in specialist units, such as signals, transport and the Royal Flying Corps (in 1918 reconstituted as the Royal Air Force). Here they could learn a useful trade without being shot at. There was a saying in the Dublin building trades that it was easier for a brickie’s labourer to become Lord Mayor than to become a bricklayer. This nepotistic culture made access to the trades a closely guarded privilege. The British army provided an escape route from permanent membership of the ranks of the unskilled.

Another reason for the declining numbers seeking war work in Britain was that by 1918 Dublin had finally secured some war industries of its own.

It had been a long struggle. Unlike Belfast, there was little in the way of industry suitable for conversion to war work in 1914. As late as 1917 pressure was being exerted by labour exchanges on unemployed workers to accept jobs in Britain. In December 1916 the Dublin Trades Council complained that unemployed craft workers were being denied benefit unless they were willing to work in war industries as labourers.13

The obvious question was why Dublin did not get its ‘fair share’ of war industries. A number of enthusiasts, including the economist E. J. Riordan, involved themselves in the All-Ireland Munitions Committee but found it as difficult to arouse Irish manufacturers to exploit opportunities as it was for the War Office to offer them. When a conference was organised for saddlery and harness firms in Dublin in September 1914 only seven out of a possible twenty companies attended. All seven landed lucrative contracts.

Another problem was that Irish samples and supplies had to be sent to Britain, adding to transport and marketing costs. The Dublin Chamber of Commerce raised the matter with the War Office in March 1915, but progress was slow, and the chamber itself did not establish an Armaments Committee to lobby for war contracts until June 1915.14 A samples depot was not established until December 1916, operating from the Irish War Office in Dawson Street; a receiving depot for Irish war supplies did not materialise in Dublin until the war was nearly over, in October 1918.

The Minister of Munitions, David Lloyd George, was far more dynamic in providing war work for Dublin—in the shape of a munitions factory—than Irish businesses were in seeking it out, making a commitment to build a munitions factory even before he met a deputation from the Dublin Armaments Committee headed by Patrick Leonard, president of the chamber of commerce, in March 1916.15 Nor did he allow the rising to disrupt his production schedule. By June 1916 the large-scale production of 9.2-inch shells and fuses had begun at the National Shell Factory in Parkgate Street. In August the committee was informed that full production would be achieved by October. In September the Ministry of Munitions established a branch office in Dublin to co-ordinate Irish production, and the plant was meeting its initial targets shortly afterwards. The Dublin Munitions Committee now concluded that its services were no longer required, and remaining funds were used to meet the expenses of the members.

It appears that poor local management ability was a more significant problem for the minister than the rebels. Two English inspectors reported that Irish factories were poorly run and, unlike their British counterparts, could not be adapted to post-war production. As Neil O’Flanagan has pointed out, ‘the replacement of the management … by directors sent over from England added salt to the wounds.’

Nevertheless the factories provided a much-needed boost to the local economy. By March 1919 the National Shell Factory in Dublin had manufactured half a million shells, worth £569,000, and fuses worth another £98,000. It accounted for 80 per cent of all munitions produced in Irish shell factories and employed the largest proportion of their 2,148 workers, the great majority of them women.16

The other bright spot on the horizon was the Dublin Dockyard Company, run by two Scottish shipbuilders, Walter Scott and John Smellie.17 The Dublin Trades Council and the newly constituted Dublin Port and Docks Board supported the establishment of the business in 1901, both bodies being keen to promote desperately needed local employment. A wise decision to agree Glasgow rates with the unions provided a ready-made formula for pay adjustments that secured industrial peace for many years.

At first the yard provided a ship repair and overhaul service for the seven thousand vessels using the port each year. Later it began to build small to medium-sized steamers, including the fishery protection vessel Helga, converted for anti-submarine warfare after the war began but best remembered as the gunboat sent up the Liffey to shell Liberty Hall during the Easter Rising.18 With the outbreak of war the yard’s owners displayed characteristic commercial acumen by securing one of the first war contracts, on 23 September 1914. It was for the repair of Royal Navy ships and any other vessels designated by the Admiralty. Trawler patrol escorts, minesweepers, destroyers, submarines and troop transports were among the vessels serviced, and the yard expanded into supplying and fitting gun platforms, guns, wireless cabins, submarine direction-finders, minelaying appliances, depth-charge throwers, paravanes (for deflecting mines from the hulls of vessels) and battle practice targets.

Shipping losses proved good news for the yard. The Dublin Port and Docks Board provided extra workshop space and water frontage for the creation of two new building berths. This allowed the Dublin Dockyard Company to supply high-demand vessels of 3,000 to 5,000 tons to the Ministry of Shipping. The move was not without its opponents. Representatives of the shipping industry on the board strongly opposed handing over the facilities, leading to accusations from public representatives across the political spectrum that vested interests wanted to keep out competition.

The trades council threw its weight behind the proposal ‘to grant these facilities to an industry of so great an importance to Dublin and Ireland.’ The position of the shipping companies and brokers was ultimately untenable in a situation where the shortage of shipping was choking the commercial life of the city, as well as preventing the creation of badly needed jobs.19 Once the opposition was overcome, the yard’s expansion in 1917 was so successful that the company had one of its vessels, the c5 collier, adopted by the Admiralty as a standard model for other yards.20 The firm also diversified into munitions through its subsidiary, Dublin Dockyard War Munitions Company, which produced 50,000 shells for the British army’s eighteen-pounder guns.

The company gave the same care and attention to recruitment, working conditions and staff relations as it did to everything else. Within a month of the start of the war it introduced a levy on employees for the Prince of Wales National Relief Fund. This fund was established to channel all charitable donations for relieving distress into one central agency. According to Smellie, employees agreed unanimously to contribute to the fund. The amounts varied from 6d to 1s a week, depending on earnings. In some instances, where men were heavily dependent on piece work, the contribution amounted to 2½ per cent of earnings. The readiness of employees to contribute was probably due in part to supervision by a committee on which all the shipyard trades were represented. Even members of the IRB, Irish Volunteers and Citizen Army, who worked in the yard in significant numbers (and used the facilities to secretly manufacture munitions), would not have wanted to appear mean. There were also significant numbers of skilled workers from Belfast and British yards. Nor did political allegiances overrule financial sense: three times as much was subscribed by employees to war bond schemes as for relief.21

The Dublin Dockyard Company’s decision to branch out into munitions preceded the establishment of the National Shell Factory; but there was plenty of work to go round. Smellie wrote later in his history of the yard: ‘It was determined to make the factory a model one … and with this in view visits were made to several private plants in England … and the best features of each incorporated in the designs.’ The factory was built of wood, ‘with a saw-tooth roof admitting abundance of light.’ The machines were laid out in rows, with wide corridors to allow easy and rapid movement of the raw materials as they were transformed from steel bars into shells.

However, ‘the getting of suitable girl labour appeared in the early stages to be a difficulty of some moment, as the contract with the Ministry of Munitions permitted only 5 per cent of the total staff to be men or boys, and included in this … were shift foremen, tool setters, tool makers and any other male labour.’ Although Dublin lacked the large reservoirs of female factory labour available in British cities, the misgivings proved groundless.

The 200 girls employed soon became highly efficient, and were quick in adapting themselves to machine work, and to all the engineering operations of shell turning, including working to gauge limits of but one or two thousandths of an inch. It was perfectly amazing to note with what deftness of hand and eye a cut was made so accurate in judgement as to satisfy forthwith the limit gauges without resort to the usual trial and error process of cut upon cut.

The first batch of ‘a dozen chosen young ladies’ was sent to the Vickers plant at Barrow-in-Furness for six weeks’ instruction, then returned to train the rest of the workers. Soon productivity was so high that the output was three thousand shells per week rather than the two thousand guaranteed by the machine manufacturers. To achieve this target the women worked alternate twelve-hour shifts on piecework rates that maximised output, and they were not likely to strike.22

Despite the efforts of men like Smellie, the Dublin munitions factories failed to keep pace with best practice as advised by the Health Committee of the Ministry of Munitions. Experience showed that twelve-hour shifts lowered productivity and caused increased sickness and absenteeism, as well as putting ‘severe mental strain’ on managerial staff. Workers on long shifts also experienced an ‘increased temptation to indulge in the consumption of alcohol.’

Of course the Irish industry was much smaller than its British counterpart, and the women lived locally, unlike Britain, where they often spent up to five hours commuting. Nor do the Dublin factories appear to have experienced the same wide social mix as the British work force, which listed in its ranks ‘dress makers, laundry workers, textile workers, domestic servants, clerical workers, shop assistants, university and art students—women and girls in fact of every social grade,’ although one group that was given preferential treatment in Dublin when it came to recruitment was soldiers’ dependants, especially wives and widows.23

Far from flocking to the National Shell Factories to seek gainful employment, many middle-class Dublin women devoted themselves to charitable war work organised by the Irish Munitions Workers’ Canteen Committee; apparently the social stigma of factory work outweighed the lucrative earnings. The Canteen Committee provided subsidised meals in the Dublin Dockyard and National Shell factories. In the canteens every worker received a free cup of tea and bun at the start of each shift. Items such as tea, coffee, cocoa, sandwiches and sausage rolls cost 1d, while a freshly cooked salmon served on a plate with fresh vegetables cost 5d. The social work model in the factories was based on the British system. This relied on Voluntary Aid Detachment networks and ‘knitters’, who operated under Mrs Hignett, the head knitter for Dublin, who had been trained personally in England by Lady Lawrence, founder of the movement. The planning was meticulous. Based on a realisation that providing subsidised meals helped raise morale as well as reducing the absenteeism caused by malnourishment and associated health problems, it provided useful war work for VAD volunteers who lacked the skills needed for other roles.

The committees of ‘knitters’ did everything possible to make the munitions workers’ dinner hour ‘jolly,’ the Women’s Work columnist of the Irish Times reported. Before they had finished their meal the workers would be

waiting to hear the news read to them. They always clamoured for this and then listened to the gramophone or sang and danced before filing back to their war work. At tea time they were back for half an hour and it seemed no time again, so crowded with work were the hours for the canteen workers before the hot supper was ready for the new hundreds on the night shift, every one of whom knew the mighty difference between all night work on a parcel of food eaten ‘where they could’ and this new regime in which delicious meals served by devoted women in attractive canteens serve to break up the hours of hard munitions work … The steaming food, the flowers, the dance, the gramophone, and the rest when necessary, all combined to vastly increase the output of shells and cartridges. If any ladies seek employment at war work of a wholesome and ennobling character they cannot do better than enrol in Mrs. Hignett’s army of workers.24

However, Lady Lawrence’s ‘knitters’ would give way to a more professional approach as full-time welfare superintendents and paid catering staff took over the task of feeding the workers. This new system had been piloted in British munitions factories and was found to be superior to the voluntary networks, although they continued to exist.

The superintendent appointed in Parkgate Street was Margaret Culhane, a sister of Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. When objections were raised in the House of Commons to her appointment, the Parliamentary Secretary to Lloyd George, Worthington Evans, told members that the appointment of professional social workers and managers such as Mrs Culhane was done through the proper procedures and had led to significant improvements on the voluntary system it had replaced.25

By early 1917 four-fifths of the munitions workers in the Dublin Dockyard were female; but this revolution in employment appears to have passed the city fathers by.26 They remained preoccupied with the rapidly changing political situation rather than the feminisation of industry. Concern over the fate of fellow-members and employees of the corporation imprisoned as a result of the rising or who had lost their job as a result of the carnage provided a humanitarian issue on which councillors could unite without having to take positions on the war. In October it was agreed to compensate workers who had lost their employment because of the rising, although the hope was also expressed that the sums to meet this generous policy could be secured from the British exchequer.

The corporation responded sympathetically to a request from the Irish National Aid Association that city employees interned for their part in the rising should retain their positions. No doubt it helped that one of the honorary secretaries of the association, Fred Allan, was also secretary to the corporation as well as a former secretary of the Supreme Council of the IRB. Alfie Byrne went a step further and proposed that the corporation call upon ‘the Irish nation … [to] unite in demanding the release of our fellow countrymen and women interned in English prisons without trial’ and for ‘an amnesty for those who have been sentenced to terms of imprisonment,’ pending which they should be given the status of political prisoners. The motion was seconded by Michael Brohoon, a Labour councillor. Not only did the corporation overwhelmingly support it but councillors agreed to having a representative from each ward actively campaign to establish an all-Ireland convention with various national and labour bodies to establish a Political Prisoners’ Amnesty Association.

The same meeting adopted another motion from Byrne condemning conscription, seconded by the recently released Alderman Tom Kelly of Sinn Féin.27

The threats posed by the war to public morality were never far from the thoughts of the councillors, or indeed of many respectable Dubliners brought up in an environment of Victorian rectitude. When representatives of the Vigilance Association attended a corporation meeting in October 1916 their views were given careful consideration. A Catholic body, its deputation was headed by Canon Dunne, president of Holy Cross College and a close friend of Archbishop Walsh. Representatives of the Irish National Foresters, AOH and many Catholic sodalities in the city accompanied the canon to express concern at the lack of adequate supervision in cinemas. Their view was shared by the Juvenile Advisory Committee of the Board of Trade Labour Exchange in Lord Edward Street. It wrote separately to the corporation, alerting councillors to the dangers facing idle adolescents who ventured into ‘certain censored films’ in any of the city’s twenty-six picture houses.

The Cinematograph Act (1909) provided for the appointment of censors and inspectors, but the corporation had never appointed any. The earliest it could now do so would be 1917, because, as the law agent, Ignatius Rice, pointed out, it would be illegal in 1916, as no funds had been voted for the purpose. The speed of the councillors’ response suggests that the lobbying power of Canon Dunne and his constituency was considerable. While powerless to finance the appointment of inspectors until 1917, the corporation readily agreed to reject an application for picture houses to be opened at 8 p.m. on Sundays rather than 8:30 p.m. It was feared that the earlier opening time could distract the faithful from evening devotions.

In October it also appointed two honorary censors, Eugene McGough JP, a gentleman ‘of independent means and education,’ and A. J. Murray, headmaster of the Central Model School. Both men would still be acting in an unpaid capacity in 1920, when they requested £78 each to cover expenses for the previous three years.28 Two honorary lady inspectors, Mrs E. M. Smith and Mrs A. O’Brien, were recruited in early 1917, when a paid corporation employee, Walter Butler, took overall charge. The ‘honorary’ was a courtesy title, as both women were full-time sanitary inspectors and monitored cinemas as an additional duty. Nor did it mean a pay increase, although their salaries were between £20 and £25 a year less than those of their male counterparts.29

The first complaint Walter Butler had to deal with was in early 1917 when a Mr M. J. Barry complained about an ‘impure, filthy poster’ exhibited by the Carlton Cinema in Upper Sackville Street for a film entitled The Circus of Death. ‘For sheer audacious and suggestive indecency,’ Barry said, it ‘had never been surpassed in his experience.’ Butler disagreed and found nothing indecent in the poster. Regrettably, no copies appear to have survived.

The emphasis in early inspections was more on safety regulations in cinemas and theatres than on the performances, in ensuring that panic bolts were installed on exit doors and that cinemas adhered to licensed opening hours, especially on Sundays. However, the Dublin Vigilance Committee was soon active again, supplemented by the activities of a Morality Sub-committee of a self-appointed Dublin Watch Committee. This group lodged a complaint about a play entitled Five Nights, written by ‘Victoria Cross’ and performed at the Gaiety Theatre in July 1918. Dublin audiences were spared the film version, which had been banned in some British cities. Charles Eason first raised the matter after refusing to print or distribute advertising material. The controversy was sufficient to persuade the Under-Secretary, James McMahon, to ask the Commissioner of the DMP to investigate, and the manager of the Gaiety was warned that ‘if anything grossly immoral were to be shewn in the play’ he could lose his licence.

But no action was taken. According to the theatre critic of the Irish Independent, the leading man in the play was an artist who ‘talks tosh, paints pictures and messes about with his models.’ He ‘strains after witticisms about models being scarce owing to girls with looks and no brains being employed on Government service.’ The female lead is his cousin, who composes ‘weird music. Being endowed with the “artistic soul,” they feel they are above and beyond all other mere people and must act differently.’30

One probable source of irritation was the popularity of the play with British officers. Soldiers generally were great patrons of the theatres and music halls. This could pose problems, as the DMP was responsible for ‘policing immorality’ in these establishments as far as civilians were concerned but the War Office dealt with military personnel. Much of the material Dubliners found morally objectionable not alone had the blessing of the War Office but was sometimes commissioned by it to boost the morale of the soldiers.

Censorship in the cinemas was less of a problem. This was the beginning of cinema’s great era of expansion. When the censorship regime came in there were twenty-two cinemas in the city, including the ‘picture houses’ that were now being built, as well as theatres that occasionally showed films, such as the Gaiety Theatre and Theatre Royal. Films featured daily as part of the Theatre Royal’s variety programme.31

One of the few cinemas to fail was the Volta in Mary Street, once managed by James Joyce, in a converted builders’ supplies and ironmongery premises. It could not compete with purpose-built new entrants to the market or, apparently, observe safety regulations and control its patrons. On 18 July 1918 there was a complaint that when patrons rushed to the exits after a fire scare they found them padlocked. In his defence the managing director claimed that on the night in question

about 100 persons had rushed in without paying and one of these shouted “fire” … The operator immediately stopped showing the film and switched on the lights. No one was injured.

Surprisingly, no fine was imposed, although cinemas were regularly fined from £1 to £20 over inadequate access to exits.32

1918 was the first full year in which cinemas were monitored. Butler and Smith made 393 inspections of premises, and they or the voluntary censors viewed 707 films. Of these, 600 were approved without changes, 55 were banned ‘on account of their immoral tone or suggestions of evil,’ and 52 were passed after excisions were made ‘to render them free from objection.’

What effect the production of lewd cinema posters or films had on republican prisoners being released from British prisons does not appear to have been recorded in any memoirs of the period. It was just before Christmas 1916, the eve of the censorship era, when the British government released a large number of internees, including the Labour councillor P. T. Daly.

Two Sinn Féin councillors, Seán T. O’Kelly (or Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh, as he now became) and W. T. Cosgrave, were less fortunate, as was Daly’s Labour colleague William Partridge. Ó Ceallaigh took the trouble to write from Reading Prison, explaining that it was not for lack of interest that he was absent from meetings. Ó Ceallaigh, Cosgrave and Partridge, unlike Daly, had been tried and sentenced for their part in the rising and not merely interned.

Lieutenant Cosgrave, the man who had identified the Nurses’ Home as the key to the defence of the South Dublin Union, had been sentenced to death, only to have his court-martial recommend a reprieve because he seemed ‘a decent man’ who had been ‘rushed into this.’ In January 1917 a corporation motion calling for his release asked rhetorically, ‘Would anyone seriously suggest for a moment that Willie Cosgrave was a criminal?’33 Councillors expressed no opinion of the character of Captain William Patrick Partridge of the Irish Citizen Army, who had been condemned to fifteen years’ penal servitude, commuted to ten years.

Undeterred by government policy, or the law, Dublin Corporation members unanimously co-opted the three imprisoned councillors in January 1917, thus making good the vacancies created by their enforced absence. This action was in marked contrast to the way in which the vacancy created by the death of the unionist councillor John Thornton had been dealt with the previous June, when the seat had been hijacked by a nationalist nominee.

The act was purely symbolic in Partridge’s case. He contracted Bright’s disease (nephritis) and was released from prison on 20 April 1917. Too ill to resume political or trade union work, he returned to his native Ballaghaderreen, Co. Mayo, where he died of a heart attack in July.34

While councillors thumbed their noses at the laws governing their own proceedings, held open jobs for rebel prisoners (as they did for employees serving with the Crown forces) and routinely condemned British oppression, the state they saw as the embodiment of foreign tyranny was finding it very hard to sack its own employees suspected of rebel activities. Dealing with subversion, even in a time of war and rebellion, was constrained by the snares of legality, not to mention uncertain guidance from above as well as resistance from employees and nationalist and labour organisations from below. A good example was provided by the case of Patrick Belton, an employee of the Land Commission, who went on to enjoy a colourful career in Sinn Féin, Fianna Fáil, the Centre Party and finally Fine Gael.

After the rising the government established a committee under Lord Justice Sankey to investigate the cases of some 1,800 detainees and other suspects. These included 90 civil servants, half of them employees of the Post Office. It was a cursory trawl, and subsequently Sir William Byrne, an English Catholic recently appointed Assistant Under-Secretary, and another career civil servant, Sir Guy Fleetwood Wilson, conducted a discreet investigation into those ‘civil servants who have been suspended from their duties owing to their suspected complicity with the recent Rebellion.’ Because of the increasing public hostility to British rule and its agents, the two men adopted a low profile, taking private rooms in Hume Street to conduct interviews rather than using Dublin Castle. They also indicated to departmental heads that they intended recommending whenever possible the reinstatement of civil servants who had been arrested or suspended. They later declared themselves appalled at the advanced views expressed unapologetically by many of those interviewed. One man, who openly admitted participating in the rising, demanded that he be reinstated because circumstances had not allowed him to shoot any British soldiers.

Of the 42 people examined, 23 were dismissed, 1 pensioned off and 18 reinstated. The most senior civil servant dismissed was J. J. McElligott, a first-class clerk who had fought in the GPO and later had a distinguished career in the Free State civil service.35 In contrast, Belton was only an assistant clerk and does not appear to have participated in the rising, possibly because he feared that it might lead to dismissal and he had a young family to feed. But he was a member of the IRB and has been credited with helping to bring Michael Collins into the organisation when they were both young emigrants in London.36 His suspected association with the rebels was first brought to the attention of his employer by the RIC. The local sergeant in Finglas reported seeing Belton ‘marching’ towards his home, Ashgrove House, in the company of four armed Volunteers on 25 April 1916. The Volunteers were encamped in a field nearby. Ordered to investigate further, the sergeant wrote back that a member of the local branch of the National Volunteers told him that Belton spoke ‘in a very derisive manner’ about their own lack of activity and said, ‘Now we are going to get some of our own back.’

While Belton was seen visiting the rebel encampment there was no evidence that he himself carried arms or wore a uniform. The sergeant admitted that the evidence was ‘meagre’ and that Belton had not previously come to the attention of the police. ‘But from what I hear recently I believe he is a dangerous man and one who would cause dissension so long as he could keep out of the conflict himself,’ the sergeant commented in a note to his superior at district headquarters in Howth. On receiving the police reports, by way of Dublin Castle, Belton’s superiors in the Land Commission ordered him to account for himself during Easter Week. He duly did so in a written statement. He told the commission he spent the Saturday afternoon working in the garden. On Sunday he walked into town ‘for papers’ after 8:30 mass in Finglas. On Easter Monday he

took a message from my wife to Miss Quin’s Hospital, 27 Mountjoy Square. Cycled round by Pillar and found that rioting had broken out. Then I went home and walked into town in evening for news, food, tobacco &c. Sojourned in my own house.

On the Tuesday he ‘came into town for news, went home and worked in the garden.’ On Wednesday,

friends en route to Cork from London called and remained for a couple of days. They were anxious about their brother in 10th Dublin’s whom they believed was in a Barracks convenient to the Park. I went in direction of Park to make inquiries of military, but there was heavy firing in that direction and I came home and sojourned in my own house.

On Thursday, Belton ‘heard there was fighting beyond Finglas & cycled out to inquire so that in case of danger I would remove my family to friends in Clonee.’ On Friday he ‘cycled out on same errand and heard there was firing at Ashbourne.’ He returned home and ‘sojourned’ there once more.

On Saturday, the last day of the fighting in Dublin, he said he went into the city and arranged for a messenger boy to deliver flour to his home from the North City Mills. On Sunday he was once more drawn towards Ashbourne. ‘Cycled out to ascertain if the fighting was coming near Finglas and was held on road by Volunteer Sentry and Police Officers who informed me all was over.’ Sunday was spent, as it must have been for countless civilians, seeking food, tobacco and other essentials in the city.

Belton’s account, given on 5 May, was probably not very different from those that could have been given by most contemporaries. But it could equally cover a multitude of subversive activities; and, unlike McElligott, Belton had no intention of making his dismissal easy for his employers.

Now that he had come to the attention of the authorities, Belton was kept under observation, and in July the RIC in Limerick and in Finglas, and the head of British military intelligence, Major Ivor Price, were reporting that Belton was collecting substantial sums for prisoners on behalf of the National Aid Association. All of this was regarded as ‘unseemly’ on the part of a government employee, and the Chief Secretary’s Office demanded that action be taken.

The Land Commission said it had no information on the aims of the National Aid Association; the police admitted that those collecting the money were not in Sinn Féin; and, crucially, there was nothing in any of the police reports to suggest ‘that Mr. Belton is guilty of complicity in the late rebellion.’ In fact the commission wrote to the National Aid Association and received a reply that it had no information on Belton, and had not received the funds referred to. This was being somewhat economical with the truth, as Belton was a member of the association’s executive committee and had certainly been fund-raising for it.37

The commission also consulted the Lords Justices but was informed that ‘their Excellencies do not propose to give any directions in the matter, which is one resting directly with the responsible Heads of the Department.’ The commission conceded in a letter to the Chief Secretary in September that while Belton ‘no doubt … would have sympathy for the dependants of those who were killed on the rebel side’ he was being recommended by the investigating commission for reinstatement. ‘I think the matter may be allowed to drop,’ the head of the commission added.

It was far from the end of the matter. By April 1917 Belton was reported to be addressing Sinn Féin meetings in his native Co. Longford during the by-election that saw a rebel prisoner, Joe McGuinness, elected to the House of Commons. Belton was reported to have boasted that he had taken part in the rising. Confronted with the allegation, he admitted speaking at the meeting but claimed he spoke only on the division of a neighbour’s farm in which he had an interest.

It took until September for him to receive a formal warning to be more circumspect in his public activities. The saga would continue. For the moment, security agents of the state, such as Major Price, could only fulminate that ‘it is not healthy for Govt. officials to identify themselves with such things.’38

Drift seemed the order of the day. A good example was the electricity supply situation in the city. In August 1915 the corporation established a sub-committee to see if savings could be made, given the high price of coal and difficulties in obtaining supplies from Britain. A consultant engineer, Patrick Walter D’Alton, a retired British army lieutenant-colonel, was commissioned to undertake the task. He completed his report by the following February and put down much of the delay to difficulties in obtaining wattmeter certificates from the Electricity Supply Department. When he did receive them he found a deviation of 511,000 units between the records of the Pigeon House power station and the official returns to the corporation. He described some of the measuring equipment readings as ‘worthless and misleading.’ He also warned that the anticipated winter load for 1916/17 would require ‘all your generating sets to be placed in a condition of perfect order during the spring and early summer of 1916,’ and required the acquisition of a new turbo alternator if resources permitted. Among the changes he advocated were

(1) a reduction in administrative overheads: the present system was ‘unduly complicated as a result of … dual control by an Engineer who is not a manager and a Secretary who is part manager’; he suggested devolving more managerial functions on the engineer;

(2) reducing the load factor on the overworked and partly outdated equipment;

(3) reducing charges to private customers;

(4) reducing the number of manual and clerical workers but not the professional engineering staff;

(5) transferring members of the outdoor staff, such as canvassers for new business and meter-readers, to the Secretarial Department;

(6) ending the monopoly of the Scottish coal supplier and ensuring greater consistency in the quality of fuel (the calorific value of the coal varied from 10,500 to 12,5000 BTU per ton, which was bad for the boilers as well as poor value for money);

(7) investing more capital in generation plant and expanding the generation and distribution system in the coming year;

(8) cleaning, overhauling, repairing and recalibrating equipment more regularly;

(9) using ‘obsolete’ Stewart engines only in emergencies, as they made ‘extravagant use of fuel.’

Even the ‘excellent’ Oerlikon turbines ‘need to be kept under close observation,’ D’Alton warned.

The problem with his report, like that of the Local Government Board on the housing crisis in 1914, was that it was so universal in its condemnation of the system that it united the entire municipal establishment against him. When Dublin’s electrical engineer, Mark Ruddle, was asked to respond, he rejected practically all D’Alton’s criticisms out of hand. They took no account of the ‘special difficulties’ under which Dublin laboured, such as distance from coal supplies and a smaller population than comparators cited, such as the London power stations. While Ruddle attributed the high cost of private consumption to the cost of fuel compared with Britain, his own figures showed that householders were subsidising business on a large scale. In the year ending March 1915 private consumers used 53 per cent of all power but contributed 78 per cent of income (£72,300).

Ruddle firmly rejected claims of overstaffing. The wage figure of £12,000 cited by D’Alton included £5,212 spent on capital works and £1,174 for work carried out by the staff of the Electricity Supply Committee on behalf of other sections of the corporation. Ruddle could also point to high interest rates as a justification for not being able to invest in new equipment. In a general defence of the existing regime he gave a potted history of the city’s electricity grid, pointing out that its capacity had increased from the equivalent of 1,000 lamps in 1891 to 600,000. Capital invested had risen from an initial £37,000 to £857,000, and income from £5,600 to over £100,000. The cost of generation and distribution had fallen from 2.43d per unit in 1904 to 1.27d in 1915 and, despite the increases in coal bills caused by the war, had been contained at 1.4d in 1916. These improvements were reflected in the financial performance of the committee. A deficit of £12,500 in 1914 had been converted into a surplus of £11,670 in 1915, and the electricity enterprise was still in surplus by £8,840 in 1916.

Ruddle had been with the enterprise from the start and had been appointed city electrical engineer in 1904. He was there long enough to accumulate many allies, including Fred Allan, secretary of the corporation, and Laurence Kettle, city treasurer, who was responsible for the administration of the electricity scheme that D’Alton found so little favour with.

Although the corporation had itself commissioned D’Alton to investigate the electricity generation and distribution system, members could not agree on how to proceed. Suggestions that D’Alton might take over were quickly dismissed. On several occasions a motion was proposed ‘to achieve the results which Mr D’Alton has outlined in his report’ by giving Ruddle ‘entire charge’ of the commercial side of the business as well as the engineering section for a trial period of two years. The former Lord Mayor Lorcan Sherlock objected, on the grounds that there was little point in asking Ruddle to implement D’Alton’s proposals when he had characterised them in his own report as ‘ignorant views, unfounded opinions, stupid suggestions and impossible of realisation.’ A compromise proposal that Ruddle be appointed general manager, that Laurence Kettle replace him as chief electrical engineer and that Fred Allan be appointed commercial manager made even less sense. In the end little was done until Kettle succeeded Ruddle in April 1919, when the latter retired because of ill-health.39

The controversy certainly took its toll on Ruddle. At a meeting of the Electricity Supply Committee in September 1917 he was accused of manipulating overtime and other payments to favour fellow-members of his ‘lodge’. Ruddle felt compelled to state publicly that he was ‘not a member of any lodge, whether Masonic, Orange, Hibernian, or Sinn Fein.’ The allegations probably said more about municipal politics than about Ruddle’s affiliation, which appears to have been Redmondite, like most senior officials. He added to his statement the intriguing postscript that he had ‘never been threatened by any members of his staff, either in or out of his office.’40

One of his last public acts was to contribute a guinea (£1 1s) to the subscription list for building a memorial to Tom Kettle and his father, Andrew, a veteran Land Leaguer, who had died within a few weeks of each other in 1916. The Laurence Kettle who replaced Ruddle was another son of Andrew Kettle. Ruddle did not enjoy his retirement for long, dying four months later.