Dublin was a divided city in 1914. It was divided by nationality, religion, class, culture and conflicting loyalties. All those divisions had deepened by 1918 and resulted in significant realignments.

The most obvious change was the increasing isolation and marginalisation of the Protestant and unionist community, which was ironic, given that the British Empire had just emerged triumphant from its greatest test. The total mobilisation of state resources to win the war brought significant benefits in the form of jobs and the redistribution of wealth to ‘separation women’ and their families in the Dublin tenements; but Lloyd George’s Government received little thanks.

The vast majority of Dubliners never saw the war as their quarrel. Indeed the Bachelor’s Walk shootings at its outbreak overshadowed more momentous events in Europe. While a relatively small number of middle-class Catholics joined the forces in response to John Redmond’s appeal for nationalists to fight for the rights of small nations, enthusiasm soon evaporated because of the crass mishandling of Irish nationalist sensitivities by the War Office and the dawning awareness of the awful price that was being exacted in blood at Gallipoli and on the western front.

Most Dubliners who joined the British army were economic recruits from the city’s working-class communities, for whom the decision had no great political or ideological significance; the first batch of reservists called up did not even have a choice in the matter. Later the chance for unskilled young men to learn a trade and break out of the rigid caste system that governed craft apprenticeships in the city provided a strong incentive to join the technical branches.

Meanwhile a gap quickly opened between soldiers at the front and civilians at home. Inevitable in any conflict, it was aggravated by the difficulty soldiers had in obtaining leave and by the unique turn of events in Dublin itself. The rising changed everything. The deaths, the looting, the destruction of property, imprisonment and repression happened on people’s doorsteps. Tens of thousands of Irishmen may have perished in Flanders, the Balkans or the Middle East, but that was ‘over there.’

All politics are local. The fact that so many soldiers who survived the war either never came home or decided not to resettle in Ireland, often abandoning their families in the process, also lessened awareness of cataclysmic events abroad. This failure to return is worthy of more study than the ‘collective amnesia’ theory promoted by some commentators.

Far from being forgotten, thousands attended annual Armistice Day commemorations in the Phoenix Park for decades. Free State ministers attended ceremonies in Dublin and London until Fianna Fáil came to power and the political establishment turned its back on Remembrance Day. But forty thousand were still reported attending the 1939 commemoration, twenty years after the war ended. During the Second World War restrictions were imposed on commemorations, as they were in Britain.1 Subsequently, as the collective memory receded, so did the numbers who attended the ceremonies. Their discontinuation at the end of the 1960s was because of concern about the public reaction to events in Northern Ireland, where a unionist tradition of a harsher kind had outlived its political usefulness. Modern attitudes towards Irish participation in the Great War have been more determined by developments since 1968 than by anything that went before.

Many families in Dublin with a unionist background continued to commemorate their fallen members within their own social circle and religious community. In the wider nationalist population the lack of enthusiasm for commemorations in the immediate aftermath of the war was certainly due to changing political sentiment. The great majority of Catholic Dubliners who served with the British forces were members of the working class, with no particular allegiance to the Crown or the Union. They rarely had a voice outside of organised labour—and organised labour in the city was totally opposed to the war effort.

The apolitical nature of Dublin working-class involvement in the First World War is demonstrated most emphatically by the failure of returning soldiers to provide a reserve army for the right, unlike many ex-servicemen in other combatant countries. Far from displaying any affection for either unionism or home rule, many ex-servicemen joined the IRA in the War of Independence, and more would have done so, particularly in Dublin, but for the misgivings of some Volunteer officers. J. J. O’Connell, assistant chief of staff of the IRA, testified to their contribution, and a high proportion of those who were accepted into the IRA rapidly rose through its ranks. In Northern Ireland there were no such obstacles to loyalist veterans of the First World War joining the RUC and its reserves when that force replaced the RIC.

The most important social initiative of the war in Dublin was the introduction of separation payments to support the wives and children of serving soldiers. This was widely denounced as a plan for degrading and corrupting Irish womanhood, especially after it was extended in 1916 to the unmarried mothers of servicemen’s children. The fact that the organisation working most closely with the families of servicemen, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, was unequivocal in its assessment of the beneficial effects of the scheme was dismissed by advanced nationalists, who saw the society as a cat’s-paw of the British establishment.

Similar disapproval extended to manifestations of independence or self-indulgence by young female factory workers, especially those in munitions factories, who were better paid than many male workers. That they would go out and enjoy themselves, helping to turn Sackville Street into an outdoor ‘low saloon’, outraged their social betters. The filth, the poverty, the prevalence of infectious disease and above all the lack of privacy in the tenements explains not alone the preference of these young women for the ‘low saloon’ of Dublin’s main boulevard but also the popularity of the pubs frequented by their elders. The social benefits of overcrowding in the slums—the camaraderie that brought neighbours together to combat shortages and share hardships—have been much exaggerated. Tenement life also left weaker tenants a prey to theft, threats and abuse by unscrupulous neighbours.

By contrast, young middle-class women who joined the Volunteer Aid Detachments or Cumann na mBan were spared the censorious scrutiny applied to munitions workers and soldiers’ wives. They too enjoyed a degree of freedom unattainable before the war, and there is no reason to believe they were any more, or less, virtuous than their working-class contemporaries. Yet the women’s patrols established by Anna Haslam were focused firmly on the behaviour of their working-class sisters and the threat this posed to society.

The threat that most preoccupied the middle classes, of all political persuasions, was the high incidence of sexually transmitted disease, a scourge whose prevalence was persistently laid at the door of the British administration. It was only after independence that it became obvious that the causes ran much deeper than the presence of a dissolute military.

The enormous amount of energy expended in denouncing the effects of prostitution has to be contrasted with the glaring failure to tackle the slums that bred this and other social problems. During the Great War nearly a thousand tenements were closed as unsafe, and 3,563 of the 4,150 families living in them were thereby made homeless. Only 327 new houses were built in a city urgently needing to rehouse 50,000 of its poorest people. While much of the blame can be laid at the door of the Local Government Board for failing to show greater alacrity in taking advantage of the funds available to British local authorities, the achievements of Pembroke Urban District Council show what could be achieved where the political will existed.

A similar situation arose with regard to wider social and health reforms. The amalgamation of the two Poor Law unions arose not out of any decision by the city to rationalise and improve services for its most vulnerable inhabitants but from military diktat. More consideration was given to ensuring that workhouse employees’ pensions were protected than to how the opportunity might be used to radically improve services to inmates. Improvements in psychiatric services were introduced by the military authorities at Grangegorman for soldiers suffering from shell shock, but many Irish staff members refused to work with them, so that a valuable learning opportunity was lost. The one great advance achieved by the forced amalgamation of the Poor Law unions was that citizens on the more prosperous south side of the city had to contribute a more equitable share to the maintenance of the city’s poor. However, the policy priority remained minimising the burden on the ratepayer. The level of pauperism in Dublin remained virtually undiminished during the war years.

A major reason for the unpopularity of the war was that it brought plenty of hardship and only a small fraction of the economic benefits enjoyed by Belfast and British cities. Dublin was unfortunate in that its principal industries did not lend themselves easily to war production. However, far more energy was spent in resisting inevitable tax increases on the drinks industry than in exploring opportunities for replacement enterprises. It was fitting that the last great rally of constitutional nationalism in the city in 1915 was to oppose heavier taxes on alcohol. Nothing better demonstrated the political bankruptcy of that movement.

The largest employment initiative was the National Shell Factory, which Lloyd George pushed through, despite the rising, with very little assistance from Dublin’s business community. The success of the Dublin Dockyard Company was achieved by two outsiders who saw opportunities that local businessmen had missed and who had to overcome ‘dog in the manger’ resistance from other port companies. Trade unions, anxious to generate jobs, were the company’s strongest supporters.2

The revival of the labour movement in the city after 1916 was one of the great achievements of Dublin workers. It was all the more remarkable given the punishment inflicted on the movement by the state, with the death or imprisonment of so many leading figures and the near-destruction of Liberty Hall. In many ways the execution of Connolly was a blessing in disguise. While he was a brilliant polemicist and propagandist, his insistence on mastering opponents in debate and his ‘prickly integrity’ led to a career marked by splits and resignations in any organisation with which he was involved. His dogmatism could also breed intolerance at times, as is illustrated by his attitude to the dependants of reservists forced to rejoin the army on the outbreak of war, as well as towards conscripts and separation women. Nor was this hostility very revolutionary: the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia by courting soldiers and nurturing their grievances, not by denouncing them.

As a martyred leader of the rising Connolly was of infinitely greater value to the movement than he would have been alive. He provided an icon sedulously cultivated by William O’Brien, an organiser of genius. O’Brien, however, was a follower rather than a leader. During his internment after the rising he became close to the rebels and began forging an alliance with advanced nationalists, especially de Valera, which would lay the basis for the continuing closeness of unions to Fianna Fáil in the decades after independence.

In many respects O’Brien’s strategy was inevitable in a society that was still overwhelmingly rural. Even in Dublin many trade unionists made it clear during the period before the 1918 general election that they would prefer to vote for Sinn Féin than for Labour candidates. If Labour had run candidates, the results of the split radical vote in the city would have allowed the Irish Party or Unionist candidates to secure seats in Pembroke, South County Dublin and possibly the Harbour division.

The only alternative Labour leaders to O’Brien were Thomas Johnson and P. T. Daly. Johnson was handicapped by the fact that he was English, spent much of the war in Belfast, and was an ineradicable moderate, despite his brief verbal flirtation with Bolshevism. Daly proved no match for O’Brien as a political infighter, and the principal result of their power struggle was the further incapacitation of Labour as an independent actor in national politics after the rising—even in Dublin. In the wider national context, the need to preserve working-class unity across the sectarian divide prevented Labour taking a position on the central constitutional issues of the day. This inevitably led to its relegation from being the movement of social, economic and national liberation envisaged by Connolly to being a niche party. Meanwhile Sinn Féin moved in the opposite direction, from niche party to national liberation movement.

Union growth in Dublin and throughout Ireland in the war years owed an enormous, if unacknowledged, debt to the British government. The state structures established to mediate in industrial disputes and to minimise disruption to war production meant de facto trade union recognition. Because Irish industry was largely peripheral to the war effort, the repressive elements of the system used to curb militancy and to try, unsuccessfully, to suppress the emerging shop stewards’ movement in Britain had no real role in Dublin. Conversely, it was one reason why a shop stewards’ movement independent of official union structures never emerged here.

While wages never caught up with inflation, the arbitration structures did allow for the emergence of a ‘pay round’ system of sorts. Industries and occupations outside the remit of the Committee on Production used its awards as a basis for their own claims, which, when successful, were used in turn by workers in controlled industries to lodge new claims aimed at restoring their differentials. Unfortunately for the workers, the dismantling of the state industrial relations machinery coincided with the post-war recession, which would see a massive counter-offensive by employers, first in Britain and then in Ireland.

The delay in the Irish employers’ counter-attack was partly due to the disturbed state of Ireland in 1921 but also to their own disunity, dating from the war years. The Dublin Chamber of Commerce, which had entered the war period greatly strengthened and unified by its victory in the 1913 Lock-out, was now deeply fractured.

Like Labour, employers were divided by the constitutional question. This eventually manifested itself in the extraordinary scenes at the Chamber of Commerce meeting in June 1918 when E. H. Andrews tried to move an address to Lord French. An ill-advised initiative by an executive still dominated by a Protestant aristocracy of capital that felt the need to endorse legitimate authority in disturbed times superseded the sensitivities of nationalist colleagues. It probably did not help that many of the chamber’s luminaries, such as Sir William Goulding, Sir Maurice Dockrell and John Good, were also leading figures in the city’s Unionist organisations and in the Freemasons.

Ironically, the most vocal opposition came from such figures as Alfie Byrne, campaigning on a ‘rights of minorities’ principle that they would themselves eschew after independence.

The alienation of nationalist businessmen from the war effort took place over a relatively short period and sprang from an early realisation that there was no percentage in it for them. They gave Redmond’s gambit the benefit of the doubt, and it might have worked if there had been a quicker and cheaper Allied victory—or even any indication by unionists and their allies in the British political establishment that something of substance would be conceded to nationalists in return for Redmond’s generosity. The Irish Party’s pursuit of the Holy Grail of home rule blinded it to the growing power of the city’s various pressure groups, including feminists, trade unionists, cultural nationalists, and social reformers. Redmond did not bother making many public appearances in the city; when he did, it was to address recruiting meetings. His principal lieutenant and his successor, John Dillon, made even fewer efforts to communicate with Dubliners, although he lived in the city.

The Irish Volunteers provided an ideal organisation around which advanced nationalists and others disenchanted with the Irish Party could coalesce. The fact that it was not a political party facilitated this role. At the same time its opposition to conscription and its objectives of national unity and the replacement of ‘Dublin Castle and British military power’ with an unspecified form of independent Irish government provided a de facto alternative political programme.

Right from the split with Redmond, a high proportion of Dublin Volunteers cleaved to the Provisional Committee. After Gallipoli, when the full scale of the sacrifices required by Britain in the war were understood, there was no question but that weekend soldiering and route marches through the city’s streets and its environs were infinitely preferable to the carnage at the front. The Volunteers also provided political education and a forum for debate in a democratic milieu that was inconceivable in the British army, where manifestations of Irish nationality were suspect and the performance of Irish troops frequently denigrated. It is no wonder, given the scant official recognition for the Irish contribution to the war effort, that Dubliners themselves felt little ownership of ‘their’ regiments as time passed and the ranks were filled increasingly from outside Ireland.

The rising forced Dubliners to choose sides, between continuing identification with the British Empire and those fighting British imperialism at home. The performance of the rebels and the military decision to use artillery made even their inveterate enemies acknowledge their courage. It also exposed the real divisions within Dublin, and Ireland as a whole, when members of the Officers’ Training Corps at Trinity College and the Dublin Veterans’ Corps assisted British troops in retaking the city centre. Irish soldiers serving in British units fighting the rebels had no choice, but in the Trinity OTC and the Veterans’ Corps every man was a volunteer, and many took substantial risks in order to participate in the fighting.

In August 1916 swords were presented to OTC officers and souvenir cups to other participants in the defence of the college. The presentations were made by Sir Maurice Dockrell on behalf of ‘the citizens and property owners of Dublin.’ Responding, the Provost, John Pentland Mahaffy, recalled that his great-grandfather had received a similar presentation from the citizens 120 years earlier for his role in combating ‘Defenderism’. While Mahaffy took pride in his ancestor’s achievements, he did so ‘with mixed feelings,’ because the Defenders of the 1790s corresponded ‘to the Sinn Feiners of the present day.’ Describing the conflict bluntly as ‘a civil war,’ he declared:

I am very sorry indeed to think that the virtues of my family should have been shown not in combating an external enemy but the dangers of home rebellion … We did not seek this war; we did not seek this quarrel with our fellow-citizens, the thing was thrust upon us suddenly in the twinkling of an eye.

Yet quarrel there now was.

Even without the executions it was inevitable that the restrictions imposed on the civilian population after the rising had been suppressed would alienate Dubliners further from British rule. Even committed unionists, such as Wilmot Irwin, found military rule irksome.

The appalling parsimony of the British government in providing compensation for civilian casualties was a lost opportunity to retrieve ground. The contrast with amounts paid to businesses and property-owners, especially the extremely generous settlement for the official mouthpiece of the Irish Party, the Freeman’s Journal, spoke eloquently of where priorities lay. Another opportunity to literally repair the political as well as the physical damage done by the rising was lost by the mismanagement of the reconstruction of the city centre. This was an area where the British government should have exercised more, not less, authority, especially when it became clear that neither the corporation nor the property-owners were going to embrace the challenge. Decoupling the compensation payments from the planning process was a fatal error.

The apotheosis of the rising came with the death of Thomas Ashe eighteen months later. Although largely forgotten today, Ashe came to personify the new nationalism in ways that even conservative elements within Irish society could embrace. (How they would have reacted had he lived is another question.) But of all the post-rising leaders of the advanced nationalist cause he was the only one of a calibre to match de Valera or Collins. In many ways he seemed to combine the best qualities of both, and with a more attractive personality than either.

Another forgotten figure is Archbishop William Walsh. He managed to bring the Catholic hierarchy, Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, the Irish Party and Labour together in a common campaign to oppose conscription. In the process he reinforced the bonds between all elements of the Catholic nationalist population and their church, from the working-class communities of Sheriff Street and the Liberties to the middle-class townships of Rathmines and Rathgar. His diplomatic ability in moulding alliances and his capacity to anticipate problems would be sorely missed during the Treaty crisis and the Civil War.

All this was happening against the background of constant shortages in the necessities of life, some of which were attributed directly to the military, such as distortions in the fodder market caused by the requirements of cavalry regiments. This in turn affected milk supplies in Dublin. As we have seen, many of these complaints were ill founded. There was no praise for the military, even for its work in feeding the population after the rising or for releasing some of its own potato stock in 1917 to break the grip of profiteering farmers on the market.

It is true that the authorities were much slower to activate price controls on essential items, such as food, in Dublin than in British cities; when they did eventually act it led to charges of interference and discrimination, even when the results were beneficial. The one occasion when the use of its draconian powers by Dublin Castle might have achieved something worth while was during the flu pandemic of 1918; but it was left to Sir Charles Cameron to take what limited measures he could with the totally inadequate resources of the corporation.

On 4 February 1919 Mr Justice Moore was presented with white gloves by the county sheriff to signify that there were no criminal cases serious enough for him to hear. He congratulated the sheriff and the grand jury on this state of affairs.3

There was never a high incidence of serious crime in early twentieth-century Dublin. Yet the dramatic decline during the First World War may not necessarily reflect an improvement in the ‘law and order’ environment—possibly quite the opposite. The 1916 Rising had, in the words of the Commissioner of the DMP, ‘rendered ordinary police duty an impossibility,’ and members of the force appear to have conducted a strategic withdrawal from the city’s streets.

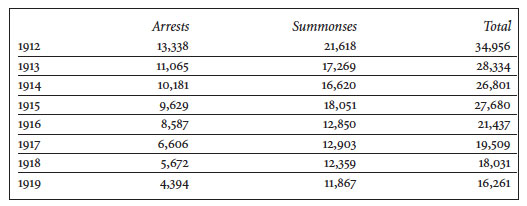

Given the low rate of indictable offences in Dublin, this retreat can more readily be seen by looking at the number of arrests and summonses served. The total number of summonses fell from 21,618 in 1912 to 11,867 in 1919; the fall in the number of arrests is even more dramatic, from 13,338 in 1912 to 4,394 in 1919.

Table 19

Arrests and summonses served, 1912–19

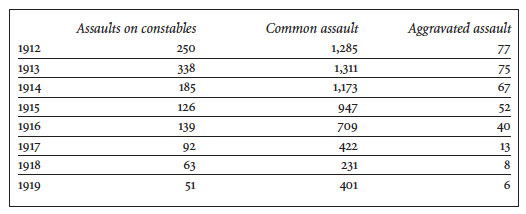

The decline in the number of assaults on DMP constables and in common assaults would also support the notion of a retreat from the streets, or at least from active law enforcement. After reaching a peak in 1913 during the lock-out, the number of assaults reported, together with attacks on property, theft and public order offences, fell steadily in subsequent years. The more structured forms of protest engaged in by the Irish Volunteers, at least until the rising, appear to have exacted a less serious toll on the DMP than the amorphous disturbances that surrounded the great industrial dispute.

However, the continuing fall in the number of assaults after the rising mirrors that in the number of arrests made and summonses served. This suggests, therefore, that there was some validity in the belief among senior figures of the British administration that the DMP had become too demoralised by 1919 to enforce the King’s writ. The scene was being set for a direct conflict between the Volunteers, the military and the future paramilitary formations of the British state. The fact that the latter bore the misnomer of the RIC fooled no-one. They would go down in history and popular memory as the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries.

Table 20

Assaults, 1912–19

One of the few unambiguous success stories of the war years in Dublin was the emergence of the allotments movement. It provided badly needed nourishment for the city, and the Irish Plotholders’ Union donated produce to the communal kitchens in Liberty Hall during the severe food shortages at the end of the war. By 1919 the area under cultivation had grown to 440 acres and the number of plot-holders to three thousand. Like the Irish Volunteer movement, it was an important educational exercise in civics and local democracy as well as meeting more immediate and mundane objectives. By 1919 Dublin Corporation had two thousand applicants on a waiting list for allotments; but, far from expanding, the movement faced the prospect of shrinking acreage as many of the sites on which crops were grown were awaiting funds for housing development.

Another success story was the mass mobilisation of women for war work. Unlike some British cities, there was a sharp class division of duties in Dublin. Working-class women went, by and large, into the factories, while occupations for middle-class recruits included nursing and organising hospital supply depots, running soldiers’ clubs, providing meals for the poor and sustaining such voluntary bodies as the NSPCC. If the leading honorary positions in such bodies continued to go to the aristocracy, there was a growing reserve of women with the leadership, organisational and professional skill to provide real benefits to the wider community—as well as the war effort—such as Alice Brunton Henry, quartermaster of the Irish War Hospital Supply Depot. The great majority of these women came from Protestant and unionist upper and middle-class backgrounds. It was the last great flowering of good works by this community before independence.

There were, of course, prominent converts among this group to radical nationalist politics and social reform movements who were prepared to challenge the status quo, such as Constance Markievicz and Louie Bennett, who involved themselves in the advanced nationalist and labour movements, respectively. Markievicz also converted in a literal sense, becoming a Catholic, one of several prominent Protestant women activists to do so. The desire to more fully legitimise their commitment to the cause of independence with fellow-revolutionaries probably played a role in the process, as well as purely spiritual motivations. This is a phenomenon worthy of more study.

Of course many Catholic middle-class women, such as Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, played a similar role in nationalist ranks to that of their Protestant counterparts. As with labour, the national question proved the rock on which the feminist movement foundered. It is one of the reasons why the advent of votes for women in 1918 failed to propel them into leadership positions in either nationalist or unionist ruling circles in significant numbers—although there were important structural obstacles to the advancement of women in society as well.

Many of the obvious changes wrought in Dublin by the war were superficial. If the commercial centre of the city had been gouged out by British artillery shells, it was soon repaired, while within a stone’s throw the city’s most glaring social problem, its slums, stood intact.

On the other hand, the gathering of the first Dáil in the Mansion House in January 1919 at least showed the willingness of a new generation of political leaders to assert control of the nation’s destiny rather than trust to concessions from London. For the first time since the crushing of the lock-out in 1913, militant hope was a viable political commodity on the streets of Dublin, even if it had assumed a greener hue.