All Watches

The Spray and Slocum were off and away, but the route they had embarked on was not even remotely the one the captain had mapped out in newspaper interviews just the week before. From the beginning he sailed as the spirit moved him. Even after the “thrilling pulse” of a send-off fanned by plenty of hype in the local press, Slocum set his own deliberate pace. His first straying from plan, while minor, suggested how important mulling and moseying were to be in the overall scheme of the voyage. Slocum made first for Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he stopped in the cove part of the harbor to “weigh the voyage, and my feelings, and all that.” He also wanted to check out the Spray after her initial run. Here he had his first experience of coming into port alone in a sizeable boat. He stayed in port for close to two weeks, the first of the many delays that were to aggravate his literary agent. But Slocum already had the kind of audience that mattered to him. Old captains gathered to hear his plans and gave him a “fisherman’s own” lantern as a bon voyage gift. He also took on dry cod, a barrel of oil and a gaff, pugh and dip-net, as well as some copper paint, with which he coated the bottom of his sloop. Before leaving, he made a dinghy of sorts by sawing a dory in half and boarding up the ends. A full-size dory was too big for the Spray, but this half-dory would do perfectly, and Slocum, ever resourceful and inventive, planned to put it to good use: “I perceived, moreover, that the newly arranged craft would answer for a washing-machine when placed athwartships, and also for a bath-tub.”

On leaving Gloucester, he sailed up the coast for a nostalgic visit to his childhood home of Brier Island. It had been thirty-five years since he left, and he’d forgotten how to navigate through the passage and “the worst tide-race in the Bay of Fundy.” He asked a fisherman for directions and realized in hindsight that he shouldn’t have paid attention, for the man was clearly not an islander: “He dodged a sea that slopped over the rail, and stopping to brush the water from his face, lost a fine cod which he was about to ship. My islander would not have done that. It is known that a Brier Islander, fish or no fish on his hook, never flinches from a sea.” Slocum got caught in the “fierce sou’west rip” and was glad to reach Westport. He felt reconnected to his home almost immediately, and stayed on Brier Island long enough to overhaul the Spray.

As he worked, he again reconsidered the route he would take. Soon after, he wrote to Eugene Hardy to let him know where he planned to sail when he left on the next full tides: “I think Pernambuco will be my first landfall, leaving this. Then touching the principal ports on S.A. coast on through Magellan Straits where I hope to be in November. So many courses to be taken after that, I can onlly then go as sircumstance and my feelings dictate. My mind is deffinately fixed on one thing and that is to go round …” Hardy and the newspaper syndicate must have wondered just when his drive to do what his mind had “fixed on” would kick in.

A month later, Slocum was still in his home province. After the Westport overhaul and a test run of the sou’west rip, Slocum made one more stop before sailing for open sea. In Yarmouth, on the southwest tip of Nova Scotia, Slocum loaded up on food and water. He also made an important purchase. He had been sailing without a chronometer, as his old one had been so long in disuse that bringing it up to scratch would have cost him fifteen dollars — an amount he found alarming. But he needed a chronometer aboard, as he explained in his typical tongue-in-cheek fashion: “In our newfangled notions of navigation it is supposed that a mariner cannot find his way without one; and I had myself drifted into this way of thinking.” Now, in Yarmouth, he found a cheap solution and bought his famous tin clock with the broken face. It was a good deal: “The price of it was a dollar and a half, but on account of the face being smashed the merchant let me have it for a dollar.” The tin alarm clock was to become a kind of running joke on the trip: to mask his true talents as a celestial navigator, Slocum used the gag of boiling his clock to keep it working.

Before setting out on the Atlantic, Slocum figured he had better let his Boston agents know what he was up to. First he explained the delay, citing “an attack of malaria at Gloucester, from working at the Sloop on the beach there in a sickning ooze.” Then he announced a major change of plans that must have mystified Hardy and the people at Roberts Brothers: “After all deliberations and careful study of rout and the seasons, I think my best way is via the Suez canal, down the Read [sic] Sea and along the Coasts of India, in the winter months, calling at Aden and at Ceylon and Singapore taking the S.W. Monsoon next summer up the China Sea, calling at Hong Kong and other treaty ports in China thence to Japan and on to California From California I believe I shall cross the Isthmus of Panama The freight agent of the Panama road wrote me that I could not get over the isthmus — we’ll see!”

On July 1, to the relief of his agent, Slocum finally “let go of my last hold on America.” After eighteen days’ sailing he reached the Azores. It was three months since he had set out on his world voyage. From Horta, on the island of Faial, he wrote to Hardy: “[I have] been trying to scribble a few lines for the newspapers but find it almost impossible to do or to think.” In Gibraltar, Slocum was informed that the Mediterranean was unsafe and that he would have to cross the Atlantic again. Forty days’ sailing brought Slocum to Pernambuco, in Brazil, where he wrote an anxious letter to Hardy. The Boston Globe had published three of his travel letters, but Slocum was unable to provide the newspapers with the regular, exciting copy they needed. What copy he did send contained dubious grammar and atrocious spelling and wasn’t spectacular enough to entice readers. The Globe was his most important customer, and Slocum, now six months into his circumnavigation, could no longer implore them to be patient. He must have realized his syndicate days were numbered: “I send one more letter I dare not look it over If it is not interesting, I can not be interesting stirred up from the bottom of my soul … It was the voyage I thought of and not me. No sailor has ever done what [I] have done. I thank you sincerely for giving my son the money.”

The journalistic venture was to founder quickly. In the fall he wrote Hardy another letter in which he said he had been obliged to sell some of the library he had been given simply to keep himself solvent. It was the last letter Hardy would receive from him. Giving up the syndicate gave Slocum back a sailor’s freedom to simply roam — to live each day in the rhythm of the voyage.

In many ways a sailor is like an actor: if he’s been in the business a long time, he can improvise just about anything. He makes it look easy, but there are years of solid training and practical experience behind his moves. He works with few props, knowing for each given scene what will spell success or disaster. The sailor’s stage is ever changing, and he learns how to conduct himself against sunny, tranquil and stormy backgrounds. He learns to hear the cues, to trust his gut, to respond to each moment as it is given. His work on the ocean captures the joy, the tragedy, the humor, and the ordinary and the extraordinary experiences of life as it is lived in the moment.

Slocum’s mind had been formed by years of ocean living. He was astute at reading the winds and currents. He could anticipate what would happen if the wind should fail or the current went against him. With his quick mind and sharp instincts, he was able to maintain a safe position while anticipating all eventualities. He understood that sailing was a free-form dance of boat, sail, wind and water. “A navigator husbands the wind” was how Slocum saw it.

The old captain went about his nautical tasks with grace, certainty and accuracy. He knew every inch of his boat. She was part of the internal calculations he made with every move on deck or up the rigging. He had the gift of being able to gauge which way to jump to grab the right rope, and of knowing precisely what to do at the right moment.

Slocum knew that the sea is completely impartial. It doesn’t care who or what sails over it. It makes no distinctions, and there is nothing personal in its actions. If it wants to make steep, thirty-foot waves and break them down on a boat, it will do just that. All a sailor can do is react with what he knows. He reefs his sails and keeps his hatches tight. He sails as hard as he can. Once he makes his pact with the sea, there is no negotiation. Off the coast of Samoa, Slocum put his skills to work with an uncompromising sea: “The Spray had barely cleared the island when a sudden burst of the trades brought her down to close reefs, and she reeled off one hundred and eighty-four miles the first day, of which I counted forty miles of current in her favor. Finding a rough sea, I swung her off free and sailed north of the Horn Islands, also north of Fiji instead of south, as I had intended, and coasted down the west side of the archipelago.”

There was hardly any buffer between Slocum, his vessel and the elements. He absorbed all her movements. At every moment he knew whether she was on course. He always listened to how the Spray “talked” to him; she spoke to him in creaks and flapping sails, and he was always listening, and acting on what she was telling him. Early on in the voyage, he had had to poke about in her workings to discover her problems, but later on he probably just knew what needed greasing or tightening up, and what needed to be repaired or replaced. She let him know when she was overtaxed and tired, and he knew enough to respect her limits.

Slocum wrote of the strength and peace his hard-earned sailing knowledge gave him: “To know the laws that govern the winds, and to know that you know them, will give you an easy mind on your voyage round the world; otherwise you may tremble at the appearance of every cloud.”

But Slocum knew more than the science of the wind. He could read water and sky — a task that demanded more instinct than skill. On his boyhood island he hadn’t needed a wind to let him know a hurricane was happening out to sea. He even knew how many days out the storm was by the swell that struck the shore. Clouds, winds, smells and currents were his second language, and he thought in their terms all his life. Sailing just off the Keeling (Cocos) Islands, Slocum noted, “I saw antitrade clouds flying up from the southwest very high over the regular winds, which weakened now for a few days, while a swell heavier than usual set in also from the southwest. A winter gale was going on in the direction of the Cape of Good Hope. Accordingly, I steered higher to windward, allowing twenty miles a day while this went on, for change of current; and it was not too much, for on that course I made the Keeling Islands right ahead.”

Slocum knew how to navigate gingerly when he had to. He watched the weather carefully and made decisions as he went concerning what route he had to take to avoid storms and rough waters. Contemplating the Cape of Good Hope, which is notorious for its stormy weather, he wrote, “I wished for no winter gales now. It was not that I feared them more, being in the Spray instead of a large ship, but that I preferred fine weather in any case.”

Above all, Slocum believed in his good ship Spray. She wasn’t a sleek greyhound of a vessel that would slip through the water; instead, she was beamy and broad and comfortable. And in heavy seas a broad, buoyant vessel is ideal for sailors with plenty of time. She didn’t take green water on deck, so Slocum didn’t worry greatly about being washed overboard. And Spray was a forgiving ship. Because she could carry her press of sail in a heavy air, Slocum could not endanger himself by putting on too much sail. She was very stiff, and had a stable platform, so he didn’t face the difficulties that arise from excessive heeling. Spray was also easy on the helm. He was thrilled by one remarkable feature she possessed: she could self-steer. Without a good self-steering setup, Slocum would have had to heave to or just stop sailing when he was tired or needed to attend to other matters. Most vessels will balance to some extent, on certain points of sail, for a certain amount of time; what Slocum was talking about was a boat that he didn’t have to steer. He boasted that while most boats will steer close-hauled on the wind, the Spray could self-steer dead down wind, wind on the quarter, or whatever. She was perfectly balanced, so he claimed.

Self-steering is achieved mostly through sail balance. A sailor steers the boat against the water’s pressure on the rudder, usually countering the wind’s pressure on the sails with the movement of the rudder. With constant wind pressure, a constant angle for the rudder can be found. Self-steering is simply a matter of taking the beckets, or lines, to the spokes of the wheel and tying them to hold the wheel in exactly the position where the rudder is perfectly countering the force on the sail. If the rudder is held over too far, it will start to operate like a brake, so finding the optimum position is key. Slocum explained the secret of working his dependable old sloop: “It never took long to find the amount of helm, or angle of rudder, required to hold her on her course, and when that was found I lashed the wheel with it at that angle.”

Slocum made a fantastic claim concerning his passage from Thursday Island, off the north coast of Queensland, 2,700 miles to the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. He arrived in July 1897, just over the two-year mark in his journey. This leg of his trip was one of his finest stretches of sailing: “During those twenty-three days I had not spent altogether more than three hours at the helm, including the time occupied in beating into Keeling harbor. I just lashed the helm and let her go; whether the wind was abeam or dead aft, it was all the same: she always sailed on her course. No part of the voyage up to this point, taking it by and large, had been so finished as this.”

For Slocum, self-steering was not a luxury but rather a necessity, for it freed his hands for other business around the sloop. To other passing boats, the Spray must often have seemed like a ghost ship. While Slocum was below, tending to whatever needed doing, the Spray was able to sail along under full canvas with no sign that anyone was on board.

In fair winds, Slocum looked after routine domestic matters, acting as minion, messmate and chief cook and bottle washer. And because he was the captain, it was also he who called the orders. Slocum had some wry musings over his many hats aboard: “I found no fault with the cook, and it was the rule of the voyage that the cook found no fault with me. There was never a ship’s crew so well agreed.” He cooked on “a contrivance of my own, with a lamp to furnish the heat.” In Montevideo he refitted himself with a stove fashioned out of an oil drum with a chimney on it and a small opening to put in wood. Although he boasted of making curried venison stews, most of his meals were really variations on the theme of boiling water. He boiled water for tea. He made chowder from boiled potatoes and boiled fish. Dried salt cod was a staple of his diet. Occasionally he baked soda bread; otherwise, at least twice a week he ate the sea biscuits he had brought along. He did have his particulars when it came to getting meals on the table. “My way is to cook my victuals as near the meal hour as possible and not allow the food to lose much time between the stove and the table,” he told Good Housekeeping magazine. And he was a connoisseur when it came to making the perfect “at sea” cup of coffee: “Ground coffee isn’t worth as much by a great deal if you’ve let it stand for a day. Add your hot water and serve at once. You mustn’t boil it.” What he didn’t point out was how complicated — in fact dangerous — even a simple operation like pouring a cup of coffee can be on a boat that is rolling and lurching.

His diet varied by happenstance, and he often made a meal out of anything edible that floated by. Spotting a lolling sea turtle, he got out his harpoon and jabbed it in the neck. He had to work hard for his supper that night: “I had much difficulty in landing him on deck, which I finally accomplished by hooking the throat-halyards to one of the flippers, for he was as heavy as my boat … But the turtle-steak was good.” Roasted turtle is said to have the consistency of a good pork chop and a delicious taste more like meat than fish. While stranded in the Strait of Magellan, he found large quantities of mussels. Slocum ate the kind of fish he didn’t have to cast a line for: “The only fresh fish I had while on the open sea was flying fish that came aboard of their own accord. I was in tropical waters most of the time and had flying fish for breakfast pretty constantly — ah! such breakfasts as I used to have! Often I’d get up in the morning and find a dozen of those flying fish on the deck, and sometimes they’d get down the forescuttle right alongside the frying pan.”

Slocum had no worries about scurvy on the trip. At every stop along the way he was certain to find local fresh vegetables and fruit. The captain drank unsweetened condensed milk, and when he had eggs aboard he’d let them sit for a minute in boiling water, claiming that this technique “hermetically sealed the pores.” Slocum kept butter fresh by dipping it in brine and sealing it. He boasted that his pickled variety was “butter that will keep as long as you want.”

When Slocum wasn’t acting as ship’s cook, there was always some chore to command his attention. A boat has a way of letting a sailor know how well he’s doing his job. If the rig is looking tatty, it’s because he’s not keeping up with his work; if the boat is looking down in the heels, it’s because he’s not paying enough attention to her. A ship’s captain is not the master of the vessel, but her servant. Any sailor gains deep satisfaction from being aboard a well-founded vessel in good condition and knowing that he’s responsible for her soundness; and this was certainly true of Slocum.

In order to carry out solo maintenance of a thirty-seven-foot wooden boat with canvas sails, Slocum had to be adept in a wide range of nautical skills. He had to be able to repair the rigging — to know how to do splicing and reeve off tackles. He had to be able to repair his own sails, and know exactly how strong to make their stress areas. Perhaps most importantly of all when it came to sail repairs, he had to be able to sew a uniform stitch so that the finished sail was smooth and even. His sail-making skills were well tested in the Strait of Magellan, after several weeks of storm damage: “I was determined to rely on my own small resources to repair the damages of the great gale which drove me southward toward the Horn, after I passed from the Strait of Magellan out into the Pacific.” Blown back into the strait, he “set to work with my palm and needle at every opportunity, when at anchor and when sailing. It was slow work; but little by little the squaresail on the boom expanded to the dimensions of a serviceable mainsail with a peak to it and a leech besides.” Slocum showed his satisfaction with a job well enough done, and not without some self-effacing humor concerning his handiwork. “If it was not the best-setting sail afloat, it was at least very strongly made and would stand a hard blow. A ship, meeting the Spray long afterward, reported her as wearing a mainsail of some improved design and patent reefer, but that was not the case.”

As a mechanic, Captain Slocum was on twenty-four-hour call. The situation often required whatever makeshift maneuver he was wily enough to envision at the time. Caught in a blustery snowstorm off Port Angosto, nearing Cape Horn, he put his skills to the test: “Between the storm-bursts I saw the headland of my port, and was steering for it when a flaw of wind caught the mainsail by the lee, jibed it over, and dear! dear! how nearly was this the cause of disaster; for the sheet parted and the boom unshipped, and it was then close upon night. I worked till the perspiration poured from my body to get things adjusted and in working order before dark, and, above all, to get it done before the sloop drove to leeward of the port of refuge. Even then I did not get the boom shipped in its saddle. I was at the entrance of the harbour before I could get this done, and it was time to haul her to or lose the port; but in that condition, like a bird with a broken wing, she made the haven.”

This haven gave Slocum a brief hiatus from wind and weather, and time to catch his breath. He tidied his cabin, lay in wood and water, and made a technical change in the Spray: “I … mended the sloop’s sails and rigging, and fitted a jigger, which changed the rig to a yawl, though I called the boat a sloop just the same, the jigger being merely a temporary affair.”

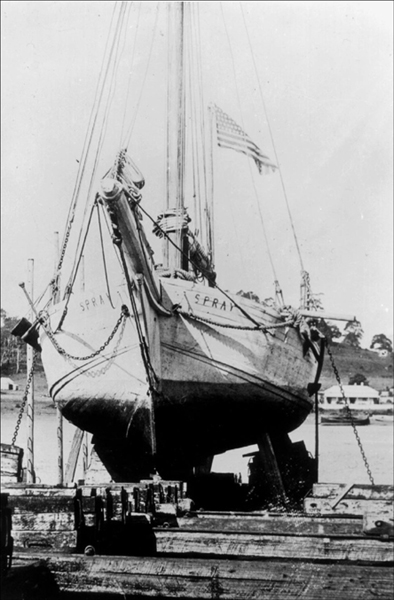

Slocum’s carpentry and shipwrighting skills came into play more than once on his three-year voyage. The water did its share of wear and tear on his beloved sloop. Besides repairing strategic parts of the rigging and caulking, he had to scrupulously maintain the hull below the water line. That vigilance was especially important in tropical waters, where he had to deal with barnacles, which threatened to coat the underside inches deep. In Tasmania he hauled out the Spray to check her “carefully top and bottom” for teredo, a destructive wood-devouring worm that can grow up to eight inches long. Another coat of copper paint was slapped on to further ensure that the wood would not be eaten away from under him.

Slocum made a number of adaptations on the voyage. At Buenos Aires he “unshipped the sloop’s mast … and shortened it by seven feet. I reduced the length of the bowsprit by about five feet, and even then I found it reaching far enough from home; and more than once when on the end of its reefing the jib, I regretted that I had not shortened it another foot.” Later, in Keeling (Cocos) Islands waters, he changed the boat’s ballast, replacing the three tons of cement ballast with mammoth tridacna shells.

The captain wasn’t always racing around deck. The Spray’s self-steering abilities afforded him the leisure to read in his cabin. “In the days of serene weather,” he later wrote, “there was not much to do but to read and take rest on the Spray, to make up as much as possible for the rough time off Cape Horn, which was not yet forgotten, and to forestall the Cape of Good Hope by a store of ease.”

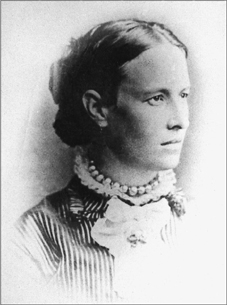

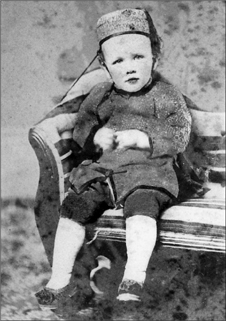

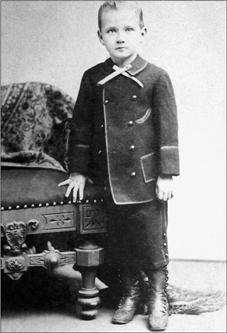

Three previously unpublished photographs given to the author by Joshua Slocum’s great-granddaughters (Benjamin Aymar Slocum’s granddaughters), Carol Slocum Jimerson and Gale Slocum Hermanet.

Virginia Albertina (Walker) Slocum, taken in Manila, some time between 1875 and 1880

Victor Slocum, taken in China (circa 1875)

Benjamin Aymar Slocum, probably age six (circa 1880)

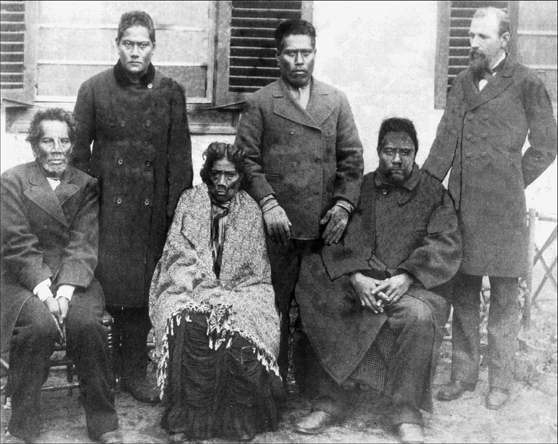

All other photographs courtesy Old Dartmouth Historical Society — New Bedford Whaling Museum

Captain Slocum and the Gilbert Islanders he rescued in the Pacific Ocean. Unknown Japanese photographer (1882)

The homemade “canoe” Liberdade in which Slocum sailed home from South America with his second wife, Hettie, and their two sons, Garfield and Victor. Unknown photographer (1889)

A watercolor by Charles Henry Gifford of the Spray as a derelict at Poverty Point, Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Informally titled “She wants some repairs” (1889)

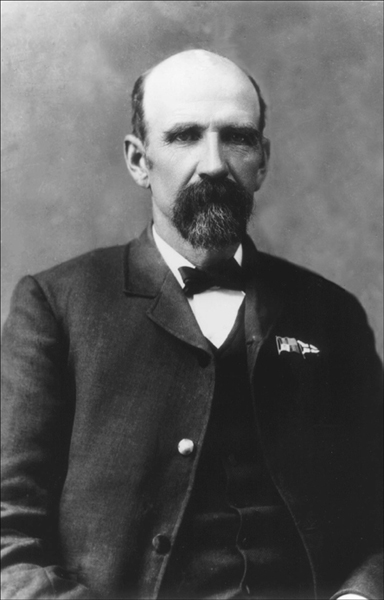

A portrait of Slocum taken about the time he had just self-published Voyage of the Liberdade. Unknown photographer (circa 1890)

A rare photograph of the interior of the Spray’s cabin. Note the rudimentary navigational instruments that Slocum used on his voyages. Unknown photographer (circa 1900)

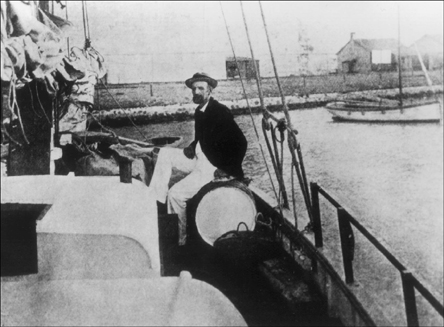

Spray moored at Gibraltar in August 1895. Slocum was on the first leg of his journey, before he decided to sail westward around the world. Ernest Lacy (1895)

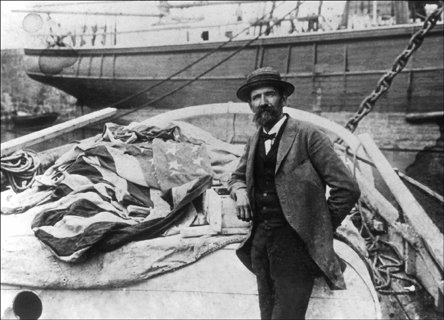

Slocum aboard the Spray in South America, after sailing from Gibraltar through the doldrums and arriving in Pernambuco, Brazil. Unknown photographer (circa 1896)

An unusual photo of the Spray hauled out at Devonport, Tasmania. The bottom was coated with copper paint to protect it from damage by mollusks. Unknown photographer (1897)

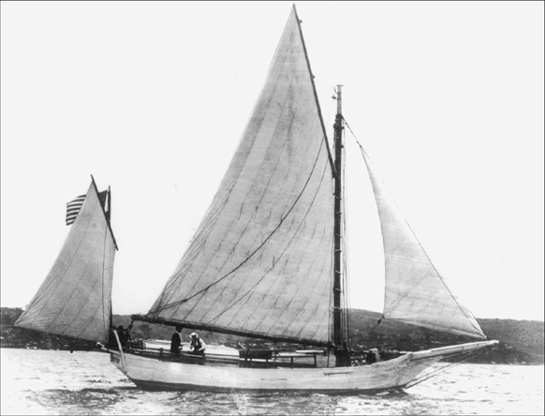

Spray under sail in Australian waters. Slocum was into the second year of his circumnavigation of the globe, having spent Christmas 1896 in Melbourne. Unknown photographer (1897)