THE DAY BEFORE GOLDBLATT’S interview at the Nailwright, Mr Sprczrensky finally got a bed on a rehab unit. For three weeks the Prof had heard about his case each Wednesday morning in the doctors’ office, and each time had only one question to ask. When was he going? Then she would see him on her procession around the beds, each week spending less time at his bedside. By the end she couldn’t even be bothered waiting for Dr Morris to examine him for signs of progress.

Mr Sprczrensky was still unable to walk. He could stand only with someone to support him. The slurring of his speech had improved, and he could raise a cup to his lips with his right hand, but lacked the strength to hold it there when the cup was full. The HO wanted to know his prognosis and Goldblatt told her that by now it was clear Mr Sprczrensky would never recover fully. Eventually he might learn to walk again with the stiff hemiplegic shuffle of a stroke survivor. The HO said goodbye to him and watched the porters push him away in a wheelchair while Mr Sprczrensky held his bag on his lap with his good arm. Goldblatt wasn’t sure whether the HO was happy to see him go or whether she would have preferred to keep him there for ever as a living means to assuage her nameless guilt.

What was happening to her?

Everyone knows it’s a dangerous profession. Those who fail to warn kids about the risks before they sign up for medical school have a serious case to answer. Alcoholism, divorce, suicide. The HO wasn’t married. But she did have a life, or at least she had once had a life, and one day she might have a life again, regardless of whether she did or didn’t have one at present. Maybe something serious was going on in her head, and her self-immolation on the altar of Mr Sprczrensky was the only way she had of expressing it.

The trick was to know whether something serious was happening before it happened. It was no great achievement to discover that it had been happening after it had happened. Goldblatt had worked with one consultant who had self-immolated himself for real, with a shotgun. Everyone knew it had happened after it happened, but there was very little use in knowing it had happened by then. It just made you feel guilty, and the whole experience suggested to Goldblatt that if you didn’t know it was happening until after it had happened, it was probably better not to know that it had happened at all. And when he wasn’t inclined to make a joke out of things – which wasn’t often, since that was the way he had coped with just about everything since he was ten – he tortured himself imagining what that consultant must have gone through in his last days, and tried to think of what he himself could have done, and wondered how he had utterly failed to see the signs.

Ludo continued to tell him that he was worrying over nothing with the HO – which only made him think that he wasn’t. After Mr Sprczrensky was wheeled off the ward to be taken to the rehab unit, and the HO had disappeared to do one of the million tasks written down on the pieces of paper in her pockets, he went to the cafeteria with Ludo for what was supposed to be a fifteen-minute break before going back to the ward to do a pleural biopsy on Mr Lister, the latest in the series of ever more desperate tests to which Dr Morris was resorting. But never in recorded history had Ludo moved within fifteen minutes once she had settled in at the cafeteria.

‘You don’t look very happy,’ she said to him, interrupting her latest whine, which Goldblatt wasn’t even pretending to try to follow.

‘I am happy,’ muttered Goldblatt darkly.

‘What is it? Not that job at the Nailwright? Malcolm, you’re too down about this job. When’s the interview?’

‘Tomorrow afternoon. You’re covering me, remember?’

‘Again?’

‘I told you last week.’

Ludo gave him a glance of profound disdain, as if even allowing the possibility that she might have forgotten – which of course she had – was beneath her.

‘And this time, if Dr Morris rings you, make it at least sound like you know what you’re doing.’

The look on Ludo’s face, if possible, got even more disdainful.

‘I’ll be leaving at one.’

‘There’s no point me covering you if you’re so negative about it. You’ll never get the job if you’re thinking like that. You have to be positive.’

Ludo... positive... The words didn’t go together. Things must be bad, thought Goldblatt, if Ludo was giving the pep talk. Really bad.

Ludo picked up her cup and drained the last of her coffee.

Goldblatt thought about Mike Coalport. Honestly, after the pre-interview, what was the point in going back there tomorrow? It was so obvious, he thought miserably. He wasn’t sure that he would even bother going. Just give them the satisfaction of having another Wise Man on the scene.

But what choice did he have? There was no other job on the horizon. And this would be the last one he could apply for without giving Professor Small as a reference. Once you’d worked on a unit for a few months, even as a locum, people would smell a rat if you didn’t include the head of that unit as a referee. Goldblatt didn’t think much of a reference was going to be forthcoming from the Prof. And maybe he should be more worried if one was, after what Ludo had told him about the previous SR. He didn’t know how things had gone so sour so quickly. He had started off really, genuinely determined to be the most biddable, compliant, tolerant, helpful, and likeable registrar the world had ever seen, and he had really, genuinely believed he was going to be able to do it. And now, after two months, it seemed the Prof could hardly look at him without some kind of spasm in her head. As for him, he could barely look at the Prof without a feeling of disgust. Even if he had ever really been capable of being biddable, compliant, tolerant, helpful, and likeable – which, he had to admit, was open to question – he knew that he was losing the will to try. And once he lost the will, he knew, he would lose the way.

He glanced at his watch. ‘Come on,’ he said, ‘are you going to help me with this pleural biopsy or not?’

‘Oh, Malcolm,’ whined Ludo.

Goldblatt got up. ‘Come on. You said you’d never seen one.’

‘I’ve got a Dermatology clinic.’

‘It can wait.’

‘Do I really have to help you?’

‘Yes,’ said Goldblatt. In the absence of the nursing staff, who had predictably announced, through Debbie, that they wouldn’t have time to assist, and the HO, who had two new admissions to clerk as well as the prospect of Emma coming to drag her away to the Prof’s private patients, he had asked Ludo to volunteer. All she’d have to do was stand by, pass him the instruments, and hold the jar in which the biopsy specimen would be deposited.

He was sure that even Ludo could manage that. Pretty sure, anyway.

Maybe Ludo was right about the HO. Goldblatt thought about her as he headed up to the ward with Ludo to do the biopsy on Mr Lister, searching his memory for the kind of signs he had missed in others in the past and which, because he had missed them then, he was concerned that he might be missing again.

In one sense, the HO had nothing to complain about. She was harassed, hounded, exhausted, and irritated out of her mind by the demands that came at her from every side. But this, after all, was the life of an HO. An HO clerks patients in, takes blood, books tests, sites drips, arranges discharge plans, gets hounded by nurses, finds out why tests haven’t been done, rebooks tests, prescribes drugs, cancels drugs, finds out why tests still haven’t been done, rebooks tests, gets hounded by nurses, rearranges discharge plans, rebooks tests, and sometimes goes home. The bit about going home is optional. A HO’s lot is to do every menial, tedious, demeaning or labour-intensive task that anyone further up the hierarchy can find a way to dump on them. If they don’t enjoy it, too bad. In a year’s time, if they’re still standing, they’ll be a senior house officer and can start the lifelong practice of dumping on HOs themselves, and will be able to enjoy watching others floundering in the role. But you can’t enjoy watching others floundering as HOs unless you’ve been an HO yourself and just shut up and got on with it. This is one of the unwritten, brutal ‘I’ve done it therefore you’ll do it’ rules that pervade the medical profession, and every HO has to abide by it or face the consequences from their seniors, who have all been HOs at one time or another, as they never fail to remind them.

But the HO faced more than her fair share of obstructions, pitfalls, and snares on the battlefield that, for her, was Professor Small’s ward. She was caught in the crossfire. On one side, Goldblatt was supposedly running the ward according to the Book of Time, and on the other side, Emma was running a black market in beds, doing a roaring trade as the front man for the manipulation scam masterminded by the local Mr Big, alias Professor Small.

The fact that Emma still wasn’t talking to Goldblatt didn’t make things any easier for her. Two or three times a week Emma put her head into the doctors’ office, checked that Goldblatt wasn’t there, and then started whispering to the HO as if she had a swag of dodgy watches under her white coat. There was a special patient the Prof had asked her to bring in. It was always a special patient. Since Emma wasn’t talking to Goldblatt, it was the HO who had to break the news to him. And each one of the Prof’s special patients apparently needed special treatment, even though this special treatment invariably turned out to be the usual Fuertler’s work-up that the HO could have organized in her sleep by now, and often did after a night on call. Emma was always cornering her when Goldblatt wasn’t around and demanding an update on the work-up’s state of progress. If any decisions had to be made, Emma usually contradicted anything Goldblatt said, on principle, and would then be back in an hour or two to ask the HO how Goldblatt had responded to make sure she hadn’t made a mistake. Then, while the HO still had twenty tests to order and three discharge forms to write and two new patients to clerk, she would drag the HO off to the private patients’ wing on the ninth floor, to spend an hour or two admitting the Prof’s private customers and organizing their work-ups.

Formally, the HO had no responsibility at all for these patients, but informally she had plenty. Private patients in NHS hospitals typically occupied a semi-corrupt twilight zone in which consultants tried to force the work on to their trainee doctors, and their trainee doctors sought tactful means of evading this extra-contractual imposition while not blowing their chances of a reference. Some consultants offered pitiful sums of money to their trainees at the end of their time on the unit, like a feudal lord throwing a scrap of meat to a grovelling peasant, amounting to perhaps one hundredth of the sums that their trainees had earned for them, and apparently expected them to be grateful. Even though it was Emma who accompanied the Prof on her visits to the private patients, it was the HO, like some palace servant scuttling around the corridors behind the walls but never being seen, on whom she dumped the tasks.

Of course, sometimes the HO did get to leave the hospital on time. No system is perfect. And she wasn’t on call every single night, or even every single weekend, so she ought to have had no problem coping with the mind-numbing exhaustion, the endless flood of trivial ward tasks, the requirement for her to deal with problems far above her level of experience, the unwillingness of her seniors to help her, the sense of aloneness when her bleep went off after midnight, and the general fear of failure that awaited her every night she was on call. In short, the HO was now deep inside the cycle of psychological trauma that is the traditional framework of existence for an HO.

She had begun asking herself the questions all house officers ask. Why not give it up? Why continue? Why do this to yourself? The house officers joked about these questions amongst themselves in the doctors’ mess, as house officers do, glancing at each other surreptitiously, wondering if any of the others would really be brave enough or desperate enough to break cover. And what about the next job, after the house officer year was over? An SHO job? More sleepless nights, more eviscerating weekends? While you were trying to study for your first part. And after that? Another SHO job? While you were trying to study for your second part? More sleepless nights, more eviscerating weekends...

‘What do you think about an SHO job in Accident and Emergency?’ the HO asked Goldblatt, walking into the doctors’ office and sitting down as he was writing up his notes on Mr Lister’s pleural biopsy. Ludo had gone off to one of her fictional Dermatology clinics as soon as the cap on the jar containing the biopsy specimen was sealed, probably worried that Goldblatt was going to expect her to label it as well, which would make for just too much work.

‘No,’ said Goldblatt, without looking up. ‘I don’t think I should settle for anything lower than registrar. Not at my stage.’

‘For me, Malcolm!’

Goldblatt smiled and continued writing.

The HO was holding a plastic specimen bag that was filled with ice cubes. Amongst the ice cubes was a syringe from which the needle had been removed, containing four millilitres of blood that the HO had just drawn from the artery at a patient’s wrist. Once capped, it had to be kept on ice until she took it down to the lab where it would be analysed for its content of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Testing arterial blood gases was a standard part of the Fuertler’s work-up, and the HO had to do it on every patient who came in.

‘I’m serious, Malcolm. What do you think?’

‘What do I think? I think it’s a stupid idea.’

‘Why?’

Goldblatt glanced at the HO. ‘Because it’s boring as hell. Fractures, stitches, and myocardial infarctions. You won’t learn anything unless you want to be an orthopaedic surgeon or a tailor. Do you want to be an orthopod?’

‘No.’

‘A tailor?’

The HO paused to consider the idea.

‘Anyway, it won’t count for anything. It won’t count towards your training unless you want to be a GP, and if you want to be a GP you’ll just end up doing it again when you get on to a training programme. So it’ll be wasted time. You’ll waste six months of your life.’

The HO put the bag with the ice and the syringe on the desk next to the computer. ‘Other people say it’s a good idea.’

‘Yeah. Well, there are a lot of idiots around,’ murmured Goldblatt, writing in the folder. ‘You want to be careful who you listen to.’

The HO crossed her arms. She tilted her head to one side and closed her eyes.

Goldblatt glanced at her. Her face was pale, there were dark shadows under her eyes. She had been on call the previous night and it looked as if she hadn’t got any sleep. He watched her, waiting to hear what he knew was coming next.

‘At least it’s shift work.’

‘So?’

The HO opened her eyes. She pushed her glasses back up her nose. ‘So I’ll get to fucking sleep!’

‘Is that all you care about?’ demanded old Professor Goldblatt. ‘You young doctors! When I was a house officer we slept on wooden boards in the back of the mortuary and were on call for the whole year without a single night off. They had to provide prostitutes because we couldn’t get out to see our girlfriends. By the end of it we hadn’t seen the sun so long we had rickets. And let me tell you, we wore our bandy legs like a badge of honour.’

‘Thanks, Malcolm.’

‘It’s no fun wearing bandy legs. Take it from someone who knows. They aren’t easy to come by, for a start. And don’t even talk about the weight of them!’ Goldblatt crossed his arms forcefully. ‘Shift work! What’ll it do to your social life?’

‘Social life!’ the HO said bitterly.

Goldblatt gave her a penetrating glance. ‘When was the last time you went out?’

The HO glanced away guiltily.

‘Tell me. I’m your registrar. You have no rights.’

‘Tuesday,’ the HO mumbled.

‘Liar!’

‘All right, Saturday.’

‘Saturday?’

‘All right, the Saturday before that. I was too fucking tired last weekend. I stayed home.’

‘By yourself?’

The HO nodded.

Goldblatt stared at her. That was bad. The HO had a boyfriend. Goldblatt wondered how much more of this he was going to tolerate.

The HO glanced around angrily. It was just possible to detect a hint of smoke coming out of her small nostrils.

She took off her glasses and rubbed them on her white coat.

‘Don’t do a Casualty job,’ said Goldblatt quietly. ‘It’s a waste of six months. It’s a racket. They buy you with golden visions and promises of sleep.’

The HO didn’t say anything. She picked the bag of ice up off the desk and stopped, looking at it, frowning.

‘What’s wrong?’ said Goldblatt.

The HO held the bag out for Goldblatt to look at. At the bottom of the bag was a thin line of vivid scarlet.

‘You didn’t put the cap on the syringe.’

‘I left the cap off! Fuck!’ Smoke was hissing out of the HO’s nostrils now. She shook the bag and the blood inside it smeared all over the ice cubes. ‘Fuck! Fuck! I left the cap off!’

‘You left the cap off,’ Goldblatt confirmed.

‘Fuck! Fuck!’ cried the HO. The words shot out on the geyser of rage that had built up inside her. She stormed out of the office to get rid of the bag and stormed back in to get another set of identification labels from the patient’s notes before going to take another sample.

Goldblatt didn’t think the HO was in a fit state to attack a plastic bag with an ice cube, much less a patient with a needle.

‘Sit down,’ he said.

‘I can’t sit down,’ the HO snapped. ‘I’ve got too much to do. I’ve got to take these gases again and then—’

‘Sit down!’ said Goldblatt

The HO looked at him resentfully. After a moment she sat down.

‘Go home,’ said Goldblatt.

The HO stood up.

‘Not yet. Sit down.’

The HO sat down.

‘You need to go home.’

‘You told me to sit down.’

‘First you need to listen to what I have to say. Then you need to go home.’

The HO sat on the chair. Like a volcano waiting to erupt.

Goldblatt gave her a long look. ‘Can the gases wait until tomorrow? Ask yourself. Are they routine or urgent?’

The HO stared at him sullenly.

‘Routine,’ Goldblatt answered for her. ‘They can wait until tomorrow. Right?’ Goldblatt waited for the HO to answer. ‘Right?’

The HO was silent.

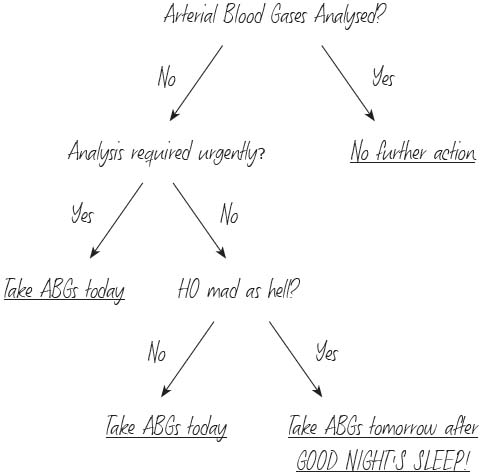

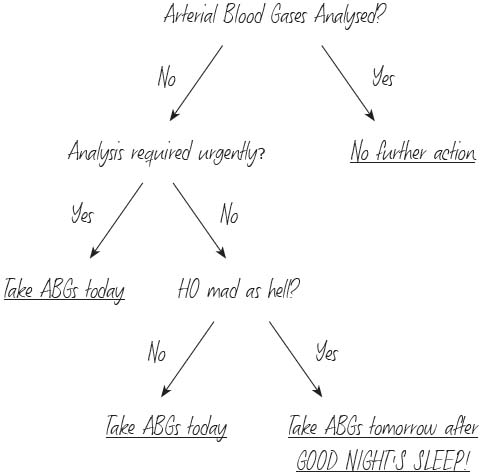

Goldblatt got up and drew one of his decision trees on the whiteboard.

The HO watched him angrily.

He sat down. ‘That’s dealt with. You’ll do them tomorrow.’

The HO stood up.

‘Where are you going?’ asked Goldblatt.

‘Isn’t that what you had to say?’

‘Sit down.’

‘I can’t. I’ve got three patients to clerk.’

‘How can you have three patients to clerk? We only got two in today.’

‘There’s a private patient on the ninth floor.’

‘Sit down,’ said Goldblatt.

The HO sat down.

‘It’s four o’clock. You’re paid to be here until five.’

‘I never go home at five.’

‘Today you’re going home at five. Go home at five.’

‘All right. Can I go now?’

‘Where?’

‘I’ve got three patients to clerk.’

‘What’s wrong with you?’ Goldblatt demanded. ‘You can’t clerk three patients. You’re going home at five. Fuck it, you’re going home now! Give me your bleep.’

‘No.’

‘Give me your bleep. Hand it over. I’ll sort things out.’

The HO held on to her bleep and stared fiercely back at Goldblatt. ‘They’re my responsibility! I have to do them.’

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake! What a load of crap. They’ve really got to you, haven’t they? They’ve sold you the whole deal. Listen, you haven’t even seen those patients yet. If I brought in eight, would they still be your responsibility? Ten? Fifteen? They’re the Prof’s patients. They’re her responsibility. It’s her responsibility to make sure there’s enough staff around to deal with them.’

The HO stared at Goldblatt sceptically.

‘You don’t believe me?’ Goldblatt gazed at this little HO who was just another one of the thousands each year duped by the hypocrisy and self-interest of their senior colleagues and supposed moral guides. ‘That’s the ethics of this fucking profession. Your profession. Our profession. I’m not making this one up. For once, this one isn’t Malcolm Goldblatt’s idea. Go and read the ethical guidelines of your own medical association. It’s a consultant’s responsibility – their ethical responsibility – to ensure that any doctor working on their unit is capable of carrying out the tasks they’re given. It’s an ethical responsibility, right? Not an option. Not a nice-to-have. A must-do. Now you tell me when any of the consultants you’ve worked for have ever bothered to come along and see for themselves that you’re able to handle a given situation. Name one. Professor Small? One of the consultants you do Takes for? Did any of them ever speak to you about the man with the VIPoma? Did any one of them ever bother to find out why you didn’t get his potassium level for three hours? Three whole hours when it was less than half the lower limit of normal? What have they done to make sure you can handle the things you come across at two in the morning? When have they ever even asked you if you’ve had a problem dealing with anything? When have they—’

He stopped. The HO was staring at him with wide, frightened eyes.

Goldblatt took a deep breath.

He smiled self-consciously. ‘Sorry,’ he said quietly. ‘Look, this is how they get you. Don’t you see? This is the lie they sell you, making you believe everything is your responsibility.’

The HO watched him. Did she understand? Goldblatt didn’t know.

‘Hand the patients over to Ludo and go home,’ he said wearily. ‘Ludo will clerk the admissions today.’

‘Ludo?’ said the HO, just as wearily. ‘Come on, Malcolm. She’s the one who goes home at five.’

‘Not today.’

‘She’ll just hand them over to the on-call house officer.’

‘Well, hand them over to the on-call house officer yourself.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not? Don’t they ever hand admissions on to you?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘So?’

‘The on-call person will hate me. I hate them when they do it.’

‘Let them hate you. Hate is what keeps the medical profession together. Listen, you have to learn to draw lines around yourself. Lines that no one can step over. People will hate you, but you have to do it. I do it. That’s why people don’t like me.’

‘I like you, Malcolm.’

Goldblatt sighed. ‘Apart from you. People don’t like me, because I draw lines. That’s how you survive.’ Goldblatt peered intently at the HO, trying to see if she understood. Because it was important. Really important. She had barely begun to live as a doctor. It wasn’t going to go away. It was going to get worse. ‘The demands are endless. They never stop until you stop them. It’s your right. Not only that, it’s your duty. To yourself. You have to draw lines. Do the things that are important, the things that really matter to your patients. The rest of it is disposable. When you’re more senior, you’ll be able to draw the lines better. But that doesn’t mean you can’t draw any now. It doesn’t mean you can’t start. Understand?’

‘Yes,’ said the HO.

‘Good,’ said Goldblatt.

‘Like Ludo?’

Goldblatt smiled. ‘You don’t necessarily need to draw as many lines as Ludo. Leave some space between them to actually do something.’

The HO laughed.

‘Look, if there’s anything you absolutely have to finish yourself, go and do it,’ said Goldblatt. ‘Not the admissions. And don’t give them to the on-call person. Ludo will do one, I’ll do the other one. Emma can deal with the one on the private patients’ ward. Don’t worry, I’ll tell her. Leave me your bleep.’ Goldblatt smiled. ‘She’ll answer that one.’

The HO grinned.

‘Work out what you have to do, then give me your bleep and go home.’

The HO nodded. ‘Can I go now?’

‘Yes,’ said Goldblatt complacently. ‘What are you going to do?’

‘Clerk the three new patients,’ said the HO, and walked out.

Goldblatt stared after her. Then he shook his head and turned back to finish the note on Mr Lister.

But maybe the HO was right, he thought. Maybe there was no viable middle ground between blind, impotent, eye-scratching rage, and crawling, canine servility. One or the other, no place for the line-drawers in between.

Maybe it was the line-drawers who ended up as the Wise Men, and the canine crawlers as Eminent Physicians.

Then he had another thought: maybe you don’t have to draw lines in order to survive.

It struck him with amazement. He felt stunned. Where had the thought come from? But maybe that was it. It would explain so much. Maybe he had been wrong all along, and everyone else was right. All the people who could have been his patrons, but hadn’t been. Even Dr Oakley. If only he had realized it earlier, maybe he wouldn’t be facing the Nailwright interview tomorrow with no patron, no support, nothing but his unbalanced CV to shield him.

For the very first time in his life, sitting in the doctors’ office on Professor Small’s unit and staring at Mr Lister’s notes in front of him, Malcolm Goldblatt thought: maybe that was only the way he had survived.