THERE WAS NO ROUND the next Wednesday morning. The Prof, together with eighty other professors, was sitting in a lecture hall at a morning meeting on postgraduate training at the Royal College of Physicians. She had rescheduled her round for two o’clock in the afternoon.

At ten past two the Prof was rushing from the consultants’ car park towards the hospital entrance. Lunch had been provided after the meeting at the Royal College, it had dragged on, and of course it was impossible to leave before it was finished. People did leave before it was finished, but it was impossible. The Prof knew she wasn’t just eating lunch – although it was a very nice lunch that she was eating, the College always catered well – she was networking. It was an important thing to do, and it also put her petty troubles at the hospital into perspective. Even without the networking, an invitation to the meeting at the Royal College of Physicians always did that. There was so much tradition in the place, so much knowledge, goodness, and virtue that the Prof almost shuddered to think of it. Being invited to a meeting there helped her remember how important she really was, and she had managed to mention it three times during her last conversation with Margaret Hayes, to help her remember as well.

She entered the hospital lobby. The sound of her own heels clattering on the floor as she rushed towards the lifts was like an adrenaline-fuelled drumbeat in recognition of her return from such an important event. The Prof was almost in high spirits. She would certainly have been in high spirits, and not merely almost in them, if not for the fact that Malcolm Goldblatt would be at the round to which the drumbeat of her feet was carrying her. Without the boy’s presence, her entire day would have been a spotless pleasure. Morning at the Royal College, lunch with the network, afternoon presiding over her round. Who could design a more spotlessly professorial day? Yet there was a spot, and the day, she knew, wouldn’t be entirely pleasant.

On the other hand, the Prof had to admit, it was also partly because of Malcolm Goldblatt that she was almost in high spirits. Paradoxically, he was a cause both of her high spirits and of her failure to fully attain them. But that was so typical of the boy, she thought, almost allowing her almost-high spirits to be overwhelmed by irritation. Everything about him was a paradox.

It was nearly a week since the Prof had asked Goldblatt whether she should get rid of him and he had threatened to think it over. In many ways it had been quite a good week.

Preparations for the Grand Round, which was being held the next morning, had come along nicely. Emma had worked until midnight every night in order to go through the entire set of Fuertler’s files, and had identified two other patients who had benefited from a delayed effect of Sorain – or could be interpreted as such. She had also found a paper that reported a similar effect in a patient in Brazil, which was one more paper than the Prof had expected her to find. Maybe there really was such an effect. And in their rehearsals, Emma had mumbled very little. It was obvious to the Prof that a lot of additional rehearsing had been going on.

Another good thing about the week was that Goldblatt, the Prof understood, had turned up to Emma’s SR ward round, as he said he would. That was very good. On the other hand, Emma, once she heard that Goldblatt was coming, hadn’t turned up, which was probably bad. It was always a bad idea not to turn up to your own round, or even to walk away in the middle of it, as the Prof herself had recently confirmed. But Emma seemed to regard missing her own round as a means of snubbing Goldblatt, which was probably good. Or maybe bad. The Prof wasn’t sure. It was probably good. Although the Prof didn’t want Emma thinking too highly of herself. That would definitely be bad.

As for what the Prof was going to do with Emma as a result of the incident in her office the previous week, she still hadn’t spoken to her about that. It was perfectly plain to the Prof that Emma was going almost insane with worry, and would do anything for a sign that she had been forgiven for her outrageous assertion about Goldblatt’s lack of respect. Naturally, that made the Prof disinclined to hurry. Emma could wait a little longer before the Prof relieved her anxiety. In fact, for a couple of days the Prof genuinely hadn’t decided whether she would forgive her, but soon came to her senses. Surely the girl’s outburst had been a Goldblatt-induced aberration of the sort that the Prof herself had experienced. What possible reason was there to think that there was anything more behind it? Emmas don’t come around every day, and to cast Emma adrift, the Prof had to admit, would be cutting off her nose to spite her face, in particular since – if she was totally honest with herself, which was a risk she felt she had to take on this occasion – some of what Emma had said might have been true, or at least it was understandable that Emma might have thought it was.

Some, but not all. As the week passed, the ‘some’ became smaller and the rest larger in the Prof’s mind. True, there may have been moments in the past, brief flashes of foolishness and misjudgement, when Goldblatt hadn’t respected her. After all, young men are rebellious by nature, the Prof understood that. It’s their hormones. They’re like bulls, stallions. Even older men could be like stallions. Take Tom de Witte. The Prof was sure Goldblatt didn’t have a girlfriend. That was certainly the problem with the boy. No one to soothe his passions, calm his storms, drain the hormones out of him.

But the events over this past week since she and Goldblatt had had their talk – or the lack of events, more to the point – strongly indicated that his disrespect – if indeed it had even existed – was in the past. What evidence was there to the contrary? None. Had he been impertinent to her? No. Had he contradicted her? No. True, she hadn’t given him the opportunity. She had avoided him like the plague, sailing past him in corridors with a frozen smile plastered on her lips and her eyes fixed on some fascinating and invisible apparition far in the distance. She didn’t dare to bleep him, relying on Emma for information, which was inconvenient because Emma had given up going to the ward for fear of bumping into him as well, and was relying for information on the house officer. But what did lack of opportunity prove? Nothing. The Prof, who prided herself on her truly legendary sensitivity to the needs, moods, and whims of others, could sense disrespect a mile off, with or without opportunity.

That was the reason that Goldblatt, despite being Goldblatt, almost made her spirits high. Whatever had happened in the past, it was clear now that he didn’t disrespect her. Rushing back from her meeting at the Royal College, where she had sat together with eighty other fine and knowledgeable professors, the Prof could barely believe that she had ever thought otherwise.

Perhaps, thought the Prof as she stood in the lift and waited for it to deliver her to the seventh floor, I’ll keep Dr Goldblatt. Perhaps I won’t get rid of him. I expect I won’t even feel intimidated when I see him at the round!

Now, Andrea, said a calmer, more reasonable voice inside her head, let’s take one step at a time.

She opened the door to the doctors’ office.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said benevolently. ‘I was at the Royal College. Couldn’t get away.’

‘We were just deciding whether to start,’ said Dr Morris, who had been forced to reschedule a pseudo-Sutherland round to fit in with the Prof’s rescheduling.

‘Oh, you should have started, Anthony,’ the Prof lied. ‘Of course you should.’ She sat down and looked around the room. Everyone was there except Jane, the South African social worker, who only dropped in to the rounds for five minutes anyway. It would take more than the absence of some useless Antipodean to upset her on such a day. And there was coffee on the desk! How thoughtful. If only it could be ever thus. The Prof glanced at Goldblatt, and blinked in a show of conciliation and good fellowship. Then she turned back to Dr Morris.

‘I see the man with the PUO has actually gone, Anthony,’ she said. ‘I was beginning to think we might never get rid of our dear Mr Lister.’

Dr Morris grinned. Emma laughed with hearty loyalty at the Prof’s excellent joke and looked desperately for an indication, a clue, a hint – no matter how small or fleeting – that the Prof accepted her abasement.

‘It was amazing the way his fever came down!’ said the HO eagerly. She started looking for his file on one of the shelves amongst a pile of notes waiting for discharge summaries to be dictated. ‘Would you like to see his charts, Professor Small? They’re here somewhere.’

‘No,’ said the Prof tolerantly, ‘I don’t think that will be necessary.’

‘It won’t take a second.’

The Prof ignored her. ‘Vasculitis, Anthony?’

‘Yes. We thought so in the end.’

‘Yes,’ said the Prof. ‘I’m sure you’re right. You started him on Prednisolone, I seem to remember. What dose, again?’

‘Sixty milligrams,’ said Dr Morris.

‘Sixty milligrams,’ mused the Prof with the air of a connoisseur. ‘Mmm, I would probably have started with forty.’

‘I thought forty,’ said Emma quickly. ‘Didn’t I, Dr Morris?’

‘We considered forty,’ said Dr Morris.

‘I knew it should be forty,’ said Emma.

Dr Morris nodded wearily.

‘Yes,’ said the Prof, glancing at Goldblatt to ensure he was gaining the benefit of this erudite discussion. The starting dose of Prednisolone in any given patient is a fine judgement, depending on the patient’s age, weight, clinical condition, and the balance of a complex set of other factors. Any young doctor could benefit from the experience of his elders, especially when one of those elders was a professor.

Goldblatt was staring at the ceiling, balancing a cup of coffee on his knee. The last few days had been dull, bleak, and depressing. He struggled to understand what was happening to his career and what he should do about it. He struggled to understand what was happening with Lesley. He didn’t know what she was going to do, but eventually she was going to do something. Did he have a day, a week, a month before she had finally had enough? Was he going to go home one night and find that she had left? Tonight? Tomorrow? And it didn’t help that at the hospital he had been on the receiving end of a lot of injured Balkan stares from Ludo, often accompanied by hair-flicking. Buying her a coffee didn’t seem to help. The silences that followed were awkward, if not downright scary. She didn’t even whine any more.

The Prof turned back to Dr Morris. ‘I’m sure sixty milligrams will be all right.’

The Prof poured herself a cup of coffee. She glanced at Goldblatt again as she lifted the cup on to a saucer.

Sister Choy opened her ward diary and rested it in the crook of her arm.

‘Shall we start?’ said the Prof.

Goldblatt nodded to himself. Let’s start, he thought. Let’s fucking start.

The HO started. The first patient was a standard Fuertler’s whom the Prof pretended to remember until it was obvious she didn’t have the faintest idea who the patient was, and Emma helped her out. The next few were standard Fuertler’s patients as well, and the Prof repeated the same piece of drama each time.

It would be interesting, Goldblatt thought, to know if she really thought she did remember them, or if she was consciously putting on an act each time. He sipped the last cold dregs of his coffee and wondered if the Prof even knew herself.

The Prof wanted to review all the test results for each patient, all the examination findings, demonstrating her complete mastery of the disease. She even picked up the Fuertler’s files, for the first time since the Constantidis Affair, and checked each one, looking up at Ludo in satisfaction. Ludo watched in dazed rapture.

Goldblatt was getting bored. The Prof appeared to be cool, confident, and totally in control, which made him nauseated as well. He had come to the round, intending to be detached, controlled, and pleasant. Honestly. But he could feel it going. He could feel it slipping away.

And why did she keep glancing at him like that, and blinking, as if there was some little joke she wanted to share with him? Every time she glanced at him, he could feel something twist tighter inside him. He felt as if it was going to snap. Stop it, he wanted to shout. Stop with the blinking!

They had already spent half an hour, and not a single clinical decision had been made. It was nothing but checking to make sure the HO had run every sacred test and Ludo had filled every holy folder. Where was the medicine? It was as if the audit commission had come to town.

Was he really going to sit through this stuff for another three months? Or until the Prof, in her wisdom, decided it would be more convenient for her if he left?

Goldblatt turned his head and stared at her.

The Prof became conscious of his gaze. Her questioning of the HO became brisker.

The HO moved on to one of Dr Morris’s patients and dealt with her in two minutes. The HO opened the next file.

‘Sandra Hill,’ she announced.

‘Oh, yes,’ said the Prof with immediate recognition, ‘she’s the lady with pulmonary fibrosis, isn’t she?’ She glanced at Goldblatt, as if to say that she could remember her patients if she wanted to.

If you couldn’t remember a patient as sick as Sandra Hill, thought Goldblatt, you ought to hand back your stethoscope and recuse yourself from the profession.

‘What’s she in for again?’

‘Pneumonia,’ said Emma quickly. ‘I told you, Prof. And Dr Goldblatt gave her a pneumothorax.’

‘Of course,’ said the Prof amiably. She looked at Goldblatt again. ‘Well, it happens to all of us.’

To all of us, thought Goldblatt. When was the last time you put in a central line? Ever?

The Prof watched Goldblatt for a moment, wanting to be sure he had noticed her gracious commiseration. Then she looked back at the HO. ‘Tell us about Sandra Hill.’

‘Shall I go over everything?’ asked the HO.

‘Yes, please.’

The HO went over everything. When she got to the part about the pneumothorax, the Prof glanced at Goldblatt again, blinking in an expression of friendly sympathy that she desperately wanted him to see. But he didn’t see it. He was leaning his head against the wall and staring at the ceiling again.

The Prof frowned. She let the HO keep speaking for a moment. Then she looked back at Goldblatt.

‘Dr Goldblatt,’ she said suddenly.

The HO stopped talking.

Goldblatt slowly turned his head and looked at the Prof.

It was twisting tighter, whatever it was inside him. The thing that was going to snap. Twisting. Twisting...

‘What’s up there, Dr Goldblatt?’

‘Where?’ said Goldblatt.

‘On the ceiling,’ said the Prof.

‘Which ceiling?’

‘That ceiling! That ceiling you keep looking at as if there’s something terribly interesting up there. What’s up there? I’m sure we’d all like to know.’

‘Up there?’ said Goldblatt.

‘Yes, Dr Goldblatt.’

Goldblatt shrugged. ‘A couple of lights.’

‘Aren’t you interested in this patient, Dr Goldblatt?’

Goldblatt gazed at the Prof in disbelief for a good ten seconds before he replied. The silence in the room grew heavy. Sister Choy lowered the communications book and laid it flat on her knees, as if she knew she wouldn’t be needing it for a few minutes.

‘I gave this patient a pneumothorax, Professor Small,’ he said at last. ‘What do you think? Wouldn’t you be interested?’

‘Yes. I would. I’d be very interested. I wouldn’t be looking at the ceiling.’

‘Where would you be looking?’

The Prof stared at him, trying to think of an answer. For a second she felt as if she couldn’t breathe. What was happening? Everything had been going so well, and now everything was going so badly and it had all just happened in a second and she didn’t know how or why or whose fault it was. She wanted to rewind. Rewind! To the part before the ceiling, please. No. She couldn’t rewind. She could only go forward.

‘I’d be looking at the patient,’ said Goldblatt to help her out. ‘I wouldn’t be sitting here talking about her for two hours.’

The Prof twitched and continued to stare. Her myasthenia was playing up again. Goldblatt recollected that he never had managed to see if she developed gaze divergence late in the afternoon.

‘We’re just discussing the case, Malcolm,’ said Dr Morris, in a despairing, half-hearted tone, as if he knew that anything he said now would be too little, too late, but he had to say it anyway.

‘And I was just looking at the ceiling, Dr Morris. We all have our foibles.’

A frosty silence filled the office.

Ludo prodded the HO. The HO looked at her angrily.

‘Go on,’ Ludo hissed.

The HO went on. She brought the Prof up to date on Sandra Hill’s admission.

‘So Mrs Hill is better?’ asked the Prof. She didn’t really ask it. She stated it.

‘A little bit better,’ replied the HO guardedly.

‘Well, she had a pneumonia and you’ve treated that. Dr Goldblatt gave her a pneumothorax but that’s resolved. She’s got pulmonary fibrosis and Dr de Witte is looking after that side of things. Why can’t she go home?’ demanded the Prof with perfect, icy logic.

Goldblatt clenched his jaw. Because she’s dying, he replied silently. And if you’d bothered to come up and see her just once since she came in, you’d know it. Because she can’t even get out of bed without oxygen. Because if she’s going to go home she needs an oxygen supply and someone to look after her or she needs to go to a hospice, and the social worker, who might be able to organize some of this, but who’s stopped coming to your round, Professor Small, because it’s such a fucking waste of time, hasn’t even been up to see her yet.

‘Well, why can’t she go home?’ the Prof demanded again. ‘Is there a reason? Or has no one bothered to arrange it?’

The HO sat there silently, looking at Goldblatt.

Goldblatt let his head fall back. It hit the wall with an audible clunk. Tighter it twisted... tighter... He stared at the ceiling, boring imaginary holes with his eyes through the ceiling tiles and electric wiring and air ducts and deep into the concrete of the floor above, still clenching his teeth to prevent himself speaking. Not trusting himself.

‘Well?’

‘She’s still a bit too ill,’ said Ludo hesitantly. ‘I don’t think we can send her home.’

‘Then what are we doing for her?’ demanded the Prof, glaring angrily at Goldblatt, who remained unresponsive to her stare. ‘What are we doing for her?’

‘There’s nothing much we can do,’ Ludo said.

Goldblatt frowned slightly. Ludo, the great evader, out in the open, taking the flak. For him. Not that she had much choice. Emma was sitting by and watching as his management of the case came under fire, smirking like a big blonde cat, and the only other person who could answer was the HO. Of course there was Sister Choy, and the physiotherapist, but it was unlikely they were going to say anything. And there was Dr Morris, but it wasn’t his patient.

But at least she was doing it, thought Goldblatt.

‘What do you mean there’s nothing very much we can do for her?’ demanded the Prof. ‘Is she on steroids?’

‘No,’ said Ludo.

‘Is she on cyclophosphamide?’

‘No.’

‘Has she had a Sorain infusion?’

‘No.’

‘No, no, no!’ the Prof repeated in growing rage. ‘Then who says there’s nothing more we can do for her?’

‘Dr de Witte,’ murmured Goldblatt, without taking his eyes off the ceiling, barely moving his lips.

‘Dr de Witte?’ demanded the Prof, staring at Ludo.

‘He took her off cyclophosphamide and steroids a couple of months ago,’ said Ludo. ‘He said her disease was so advanced there wasn’t any—’

‘Give me those notes!’ cried the Prof.

Potemkin jumped up, tore the notes out of the HO’s hands and presented them to the czarina. She stood protectively beside the Prof as the Prof started to flick feverishly through the folder. Dr Morris got up and looked over the Prof’s other shoulder. Finally the Prof stopped at the most recent letter from Dr de Witte’s clinic and lapped it up greedily. She looked up in triumphant scorn.

‘Dr de Witte did not say that,’ she announced, staring at Ludo with hostility. ‘It was his SR, Dr Ramsay. Dr de Witte was away the last time she went to clinic. Dr Ramsay saw her instead. I don’t trust Dr Ramsay. I wouldn’t trust anything that doesn’t come from Dr de Witte himself!’

Nothing like a personality cult, thought Goldblatt.

‘Andrea,’ said Dr Morris, who had read the letter over her shoulder. ‘This assessment seems very reasonable.’ He reached down and turned to the previous letter. ‘And Dr de Witte says more or less the same thing himself at the previous visit.’

‘I don’t trust Dr Ramsay!’ the Prof repeated, as if it were the one last thing in the world of which she was certain, shaking her head jerkily and clutching the notes to her breast.

‘All right,’ said Dr Morris, sounding like the exhausted parent of a spoiled three-year-old. He sat down. ‘Why don’t we arrange for Mrs Hill to go to Dr de Witte’s clinic next week? We’ll keep her in until we get his opinion. In the meantime, we’ll see if we can set things up to discharge her after that, if it’s appropriate. What day is his clinic?’

‘Tuesday,’ said Potemkin, seeing that the czarina was too preoccupied to answer.

Dr Morris turned to the HO. ‘Will you organize that?’ he said, thinking that the Prof could probably organize it a lot more quickly with Dr de Witte herself, if half the rumours about them were true. ‘Find out if Dr de Witte will be there next week, and tell his SR that Professor Small has specifically asked for him to see Mrs Hill personally. All right? We want Dr de Witte to see her himself. If there’s a problem, let me know and I’ll give the SR a call.’

The HO nodded and scribbled a note on one of her bits of paper. Then she looked at the Prof, waiting for her to give the notes back. The Prof was staring vacantly at the floor, the notes still clutched to her breast. The HO didn’t think it would be wise to prise them loose.

‘Go on,’ said Dr Morris quietly. ‘Who’s next?’

‘Mrs Whittecombe,’ said the HO.

‘All right,’ said Dr Morris, ‘tell us about Mrs Whittecombe.’

‘And in the meantime put her on cyclophosphamide and Prednisolone,’ the Prof burst out, suddenly coming to life. ‘We have to do something. How old is she?’

‘Mrs Whittecombe?’

‘No! Sandra Hill!’

‘Forty-two,’ said the HO.

‘Forty-two! Forty-two!’ shouted the Prof, as if this were the most harrowing age in God’s catalogue. ‘I can’t just sit here doing nothing while a forty-two-year-old woman is dying.’

Goldblatt thought the Prof was underestimating herself. She had done a pretty good job of it over the last week.

‘But we’ve... made her Not For Resuscitation,’ stammered the HO.

‘Who made her Not For Resuscitation?’ demanded the Prof apoplectically.

Goldblatt closed his eyes.

‘Dr Goldblatt,’ whispered the HO.

‘Dr Goldblatt! Dr Goldblatt had no right to do that. No right at all! Dr Goldblatt’s going to have to answer to me about that. You make her For Resuscitation. Make her For Resuscitation right this minute.’

Right this minute? Another twist. Tighter... tighter...

‘And start her on cyclophosphamide and Prednisolone.’

‘But Andrea,’ said Dr Morris, ‘we were going to ask Dr de Witte to see her next week. If her condition’s as advanced as Dr Ramsay suggested, then a few days more or less of treatment isn’t going to make any difference.’

‘I don’t trust Dr Ramsay! She may be dead by next week, and Dr Ramsay will have killed her. I can’t just stand by and do nothing while she dies.’

Yes, you can, thought Goldblatt. It was all any of them could do for her.

He had seen Sandra Hill every day for the past week. More than once every day. He had become accustomed to her tired smile and wry resignation. There was nothing he would have wanted more than to make her well. If he could have given her a new pair of lungs, he would have. He’d have given her his own. But he couldn’t. He knew what she wanted. He had talked with her. He had sat on the edge of her bed and listened to her, even when she wasn’t saying anything. He knew that she understood. She had come to the end. She had had every treatment she could have. She no longer felt angry. She no longer wondered why it was so unfair. She had been through so much. She was tired. When would peace come to her?

He didn’t want to stand by and watch her die. But it was all he could do, the best he could do for her. Give her comfort as she died. Ease her suffering. Help her when the time came, if he could.

‘All right,’ said Dr Morris reluctantly, feeling more like a psychological crutch than ever and despising himself even as he allowed the Prof to lean on him. He turned to the HO. ‘Put her on cyclophosphamide, twenty-five milligrams—’

‘Fifty milligrams, Anthony.’

‘Fifty milligrams. And Prednisolone – forty?’

‘Sixty.’

‘Sixty milligrams a day. All right?’

The HO stared at Dr Morris. Then she glanced at Goldblatt.

Ludo watched with horror. She knew what was going through the HO’s mind. Goldblatt’s latest principle, the most dangerous of all. Understand what you do. Understand what you do or don’t do it at all.

Goldblatt met the HO’s questioning eyes.

SNAP!

‘No,’ he said.

‘Malcolm...’ said Dr Morris plaintively.

‘No,’ said Goldblatt.

Dr Morris buried his face in his hands.

The Prof was staring at Goldblatt, speechless with rage, disbelief, and the old, bitter sense of inferiority that nothing she had achieved in her life had ever been quite able to bury.

‘Professor Small,’ Goldblatt said quietly, ‘we treat patients... in order to treat patients. Not to treat ourselves. It’s as hard for me to see a forty-two-year-old woman die as it is for you. But Sandra’s still going to die. The drugs you want to give her, are they going to make her last days easier? Is that what you’d want? Someone to give you a drug as toxic as cyclophosphamide just so they could give themselves the illusion they were doing something?’

‘I’m not—’

‘I’m sorry. No.’

Goldblatt’s tone was hard. What was wrong with her? He stood up. Something had taken control of him. He recognized the feeling, the same one that had swept over him in the interview at the Nailwright when Iron Balls had asked why he had done a law degree, and a minute later he had blown the top off his scalp and had told old Iron Balls exactly why he had done it. It was getting harder and harder to hold on to his head nowadays.

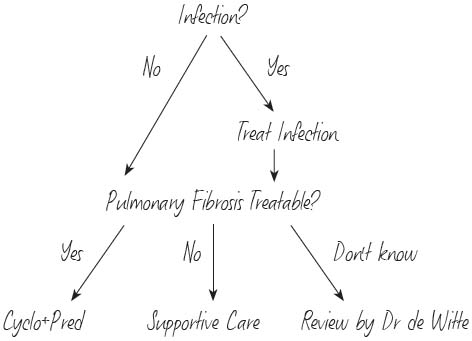

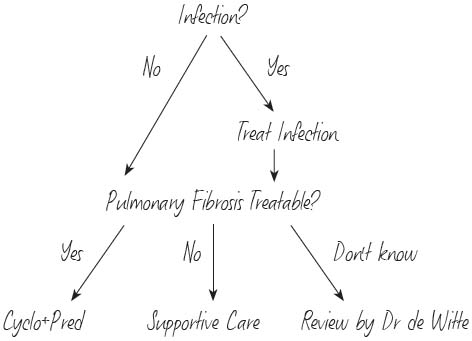

He found himself standing beside the whiteboard where he had drawn so many decision trees for the HO. But this one wasn’t going to be for her.

‘It’s very simple, Professor Small.’

He drew. Calmly. Ferociously. He could hear nothing at all from anyone behind him in the time that it took him to complete it. The marker squeaked very faintly as he drew it over the surface. The time was endless and yet it was over before it began. It was outside time.

He turned around and stared straight at the Prof, sending a searingly cold gaze into her cloudy, veiled eyes.

‘Where are we? We’ve treated Sandra’s pneumonia, so we’re here,’ he said, turning back to the board and pointing at ‘Supportive Care’. ‘But because we all hate Dr Ramsay, we’ve moved to here,’ he continued, drawing his finger across to ‘Review by Dr de Witte’. ‘But we’re not... here!’ he concluded, stabbing ‘Cyclo+Pred’ and pushing his finger hard into the words until they were broken and smeared and dead. ‘We’re not here.’

Goldblatt turned back to the Prof. She was looking away. Catatonic. A slight tremor rocked her body.

Goldblatt took his finger off the board. He dropped the marker and sat down.

There was an awful silence. It was as if a cloud of gas was choking everybody. Emma stared at the Prof in foreboding, desperately trying to work out whether this was going to make things better or worse for her.

‘Go on,’ said Dr Morris eventually to the HO in a hushed voice.

The HO looked at him.

‘Mrs Whittecombe,’ Dr Morris prompted her.

The HO nodded. ‘Mrs Whittecombe,’ she said hesitantly.

It took the HO about six minutes to get through the remaining patients. The only interruptions came from Dr Morris, who clarified a point here and there. The Prof was silent. She stared vacantly at a point on the floor beside one of the desk legs.

They went out on to the ward. Like any piece of show business, the round had started, so it had to be finished. Dr Morris conducted it, and the Prof stumbled along behind. She was silent. Her face was grey and her head trembled. She smiled automatically when the Fuertler’s patients greeted her, as if even the acclaim of her adoring public could barely penetrate the haze of her injured self-absorption. Sister Choy hovered nearby, waiting to catch her if she fell.

When they came to Sandra Hill, the Prof just stood there as Dr Morris examined her. Sandra took off her oxygen mask and whispered Hello, and the Prof produced a fragile smile and kept it there, frozen in place, until they went on to the next bed.

As soon as they left the last patient, the Prof disappeared. Dr Morris, despising himself again, followed her. Goldblatt, Emma, Ludo, and the HO were left standing in the ward corridor with the notes trolley. There was a big sense of anticlimax in the air. Or it may have been preclimax. Goldblatt wasn’t sure. But there was a climax lurking somewhere nearby, that much he knew, and this wasn’t it.

‘Coffee?’ said Ludo.

Everything was wrong. They had trooped down to the cafeteria together. Emma hadn’t run away from him as soon as she could. And then she actually spoke to him. She said, ‘What do you want, Malcolm?’ and he said, ‘Coffee,’ and she went over to the counter and bought it. That was bad. That was very bad. Goldblatt knew he was in trouble.

They sat there reflectively, the four of them, sitting around a table just like a real medical team in which everyone actually talked to each other.

Finally Ludo said to Goldblatt: ‘You should have seen the Prof’s face when you drew that decision tree.’

The HO nodded.

Ludo laughed cruelly. ‘I thought she was going to cry.’

Emma couldn’t suppress a guilty smile. Then her bleep went off. She got up to answer it at one of the phones on the wall.

That would be Dr Morris organizing a debrief, thought Goldblatt.

It wasn’t.

Emma rushed out of the cafeteria, leaving her tea to get cold.

Ludo laughed again, watching her go.

‘You didn’t think it was so funny at the time,’ said the HO.

‘No one thought it was funny at the time,’ said Ludo. ‘Things like that are only funny later.’

True, thought Goldblatt. But not everyone gets the joke.

After ten minutes Emma came back.

‘Guess who that was!’ she said breathlessly, her face flushed.

No one guessed.

‘It was the Prof! Guess what?’

No one guessed.

‘She just gave me three concert tickets she happened to have spare for tonight! Isn’t that great?’

‘Three?’ said Goldblatt. ‘What a curious number.’

‘Anyone want to go?’ asked Emma, ignoring him.

‘I’m on call,’ said the HO.

‘Come on, Ludo,’ begged Emma, ‘I don’t have anyone to go with. The Prof will ask me what it was like tomorrow. She’ll ask me who I went with, too.’

And what had happened to Emma, Goldblatt wondered. Suddenly she couldn’t lie any more?

‘What is it?’ asked Ludo.

‘Dvořák.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Music,’ said Emma. ‘Come on. It’ll be good.’

Ludo shrugged. ‘All right.’ She glanced pointedly at Goldblatt. ‘I’ve got nothing else to do.’

‘Great!’ cried Emma.

Goldblatt watched in bemusement. What was she so excited about? Emma was almost jumping from foot to foot, clutching her white coat around her and flushing with pleasure.

‘Isn’t this great? It’s fantastic! The Prof’s not...’ She stopped, suddenly realising that if she said any more everyone would know how desperate she had been for a sign that Prof wasn’t going to crush her like a beetle. ‘I’ll bleep you at six,’ she said to Ludo. ‘We have to be there half an hour before it starts to pick the tickets up.’

‘There’s still one more ticket,’ Goldblatt called after her as she left, but Emma didn’t turn back.

Goldblatt looked at Ludo. She watched him for a moment from under her drooping lids. Then she threw back her hair. She grabbed her white coat and got up, saying something about a Dermatology admission.

‘Malcolm?’

Goldblatt turned to the HO.

‘What do we do about Sandra Hill?’

Goldblatt nodded. It was a good question.

Dr Morris had already answered it. When Goldblatt and the HO went back up to the ward they found Sandra’s drug chart lying on the desk in the doctors’ office. Dr Morris had been back and written up the Prednisolone and cyclophosphamide that the Prof had demanded.

Goldblatt shook his head in resignation. Sandra was dying anyway, but the unit had to live on. He held out the chart to the HO. ‘Make sure she gets plenty of fluids. Write her up for three litres a day IV and keep an eye on her urine output. The cyclophosphamide will burn her bladder raw if she runs dry.’

The HO nodded and took the chart. ‘Malcolm,’ she said, ‘I wouldn’t have gone to that concert.’

‘Thanks,’ said Goldblatt.

‘Did you hear what it was? Dvořák!’

Goldblatt smiled.

The HO grinned.

Not for the first time, Goldblatt felt like tousling her short red hair. ‘Don’t be too picky,’ he said. ‘It isn’t every day you get a present from your Prof.’

Goldblatt was wrong. It seemed that the Prof was in an unusually generous mood, and Goldblatt himself wasn’t going to be left out. His gift would be there the next morning, waiting in a sealed envelope on the desk in the doctors’ office.

But in the meantime, there was one more night to get through.