Calm breathing

Calm breathingChapter 4

The Treatment of OCD

This is the most important chapter of the book because it provides you with details on treatment of your child’s OCD. In this chapter, you will learn the specifics of how cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is used for OCD. As stated, the research shows that CBT is the most effective approach for treating OCD (and anxiety); in particular, Exposure/Response Prevention (E/RP) is used to address the behavioral manifestations of the disorder. My goal is for you to be so informed and so clear about what effective treatment looks like that it will guide you in ensuring that your child’s treatment provider is actually using CBT and giving your child every strategy possible to overcome her OCD. If you find yourself in the position in which you know more about CBT than your provider, it’s either time to find a new provider or ask that yours receive training to use the best methods in working with your child (you can always give your provider this chapter to read).

There is no easy fix or quick solution for OCD. The treatment involves work, commitment, and regular practice with E/RP. With determination, however, OCD can be treated completely, or at least, symptoms can be so effectively managed that they no longer interfere with your child’s ability to live life without impairment. Not all children with OCD are the same. Some will require additional treatment, such as pharmacological interventions, or more intensive treatment, such as inpatient hospitalization; guidance for this is included in the next chapter.

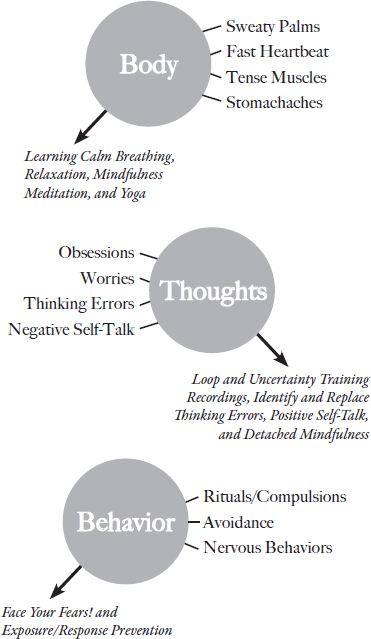

Successful treatment of OCD involves addressing the three parts: body, thoughts, and behavior. Most of the work is going to be on the thoughts and behaviors. The treatment process introduces strategies for each part, in order. I start by teaching relaxation and breathing strategies and other ways to calm the body, then move into the techniques used to address the thoughts component, and then while the first two continue to be practiced, I begin to help the child face her fears by doing the behavioral exposures.

Figure 3 includes an overview of the treatment techniques used for each part—we will go through each in detail.

Body:

Calm breathing

Calm breathing

One-nostril breathing

One-nostril breathing

Progressive-muscle relaxation

Progressive-muscle relaxation

Exercise

Exercise

Yoga

Yoga

Meditation

Meditation

Thoughts:

Loop recordings

Loop recordings

Uncertainty training recordings

Uncertainty training recordings

Positive self-talk

Positive self-talk

“Stamping” it “OCD”

“Stamping” it “OCD”

Distraction

Distraction

Identify and challenge cognitive distortions

Identify and challenge cognitive distortions

Detached mindfulness

Detached mindfulness

Attention training technique

Attention training technique

Behavior:

Create a ladder of anxiety-provoking situations in order from easiest to hardest (face your fears)

Create a ladder of anxiety-provoking situations in order from easiest to hardest (face your fears)

Exposure/response prevention (E/RP)

Exposure/response prevention (E/RP)

FIGURE 3. Treatment techniques for the three parts of anxiety.

Addressing the Body Symptoms

Calm Breathing

Many children with OCD have physiological manifestations of anxiety. They may seem on edge or restless or have a hard time winding down at night. Learning how to relax one’s body and regulate one’s breath is essential for managing stress and can also be useful when doing the E/RP work. To teach calm breathing, I have the child lie down on a yoga mat on the floor with a foam block placed on his upper chest. He should practice breathing in slowly through the nose and out through the mouth, allowing the air to travel all the way down to his lower belly, causing the lower belly to slowly rise and fall while the block on the chest remains still. Many children find that at first they have a hard time keeping the block still, or will push their lower belly out before the actual breath has entered into the belly. They should slowly inhale through the nose for the count of 4 and slowly exhale through the mouth for the count of 6 (it’s better for the exhale to be longer than the inhale). With practice, they will learn how to keep the block from rising. This natural way of breathing (where the breath goes into the lower belly) is called lower diaphragmatic breathing.

One-Nostril Breathing

The second breathing technique is “one-nostril” breathing. I have the child hold one nostril closed while keeping his mouth closed, and then slowly breath in and out through only one nostril. Start with breathing in for the count of 5 and out for the count of 7, then gradually increase it to the count of 10 in and 12 or longer out. This pattern of breathing will force a calm breath, and doing this for 5 minutes leads to a physical state of deep calm. With both breathing techniques, it is essential to master them while calm (it won’t work well if your child tries to do the breathing once he is activated or anxious). Once mastered when calm, he will be better able to know what he is aiming for (in terms of physical calmness) when he is anxious. These breathing strategies are particularly beneficial for children who have stomachaches and gastrointestinal issues as a symptom of their anxiety.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

Another technique to relax the body is progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). PMR is when you tighten and hold, then relax and release each muscle group in the body. The goal is to be able to notice when one’s muscles are tense and be able to immediately relax them. Starting with her hands, have your child make fists (like she is squeezing the juice out of a lemon) and hold it for 5 seconds, then release it. Have her notice what it feels like when her muscles are tight versus when they are loose and relaxed. Using this formula of tightening-holding-releasing, while noticing the difference between tense and relaxed muscles, the child moves on to the arms, then shoulders, back, abdomen, legs, feet, and face; then, as a last step, the whole body all at once. With practice, children learn how to quickly relax their bodies and let go of any tension that they are holding onto. This gives them greater control over their bodies’ responses to anxiety situations.

Exercise and Yoga

Exercise is another great way to release tension and manage anxiety in the body. Doing 20–30 minutes of daily cardiovascular training can be quite beneficial. It really helps with the mind-body connection, as working out the body usually clears the mind. Similarly, yoga is wonderful for kids with OCD. It teaches them to be still and in the moment, and to “unite” the mind and the body (the word yoga means “to join” or “unite”); a short routine of five poses in 15 minutes is a great starting point. For example, when a child is in a handstand against the wall, she is not thinking at all; rather, she is focusing only on doing the handstand and feeling what it is like to be fully in her body. Children 10 years old and younger may enjoy using Yoga Pretzels, which are colorful cards with easy-to-follow steps to get into a variety of yoga positions. Older kids may benefit from watching a video online or trying a teen yoga class.

Meditation

Finally, children who learn how to meditate will get to have the experience of suspending their thoughts while being in “being-ness” and hanging out in direct awareness. With practice, deeper states of awareness can be reached. There are many apps that can teach meditation (see the Resources section for a list). About half of the children I see embrace the recommendation to learn meditation; it’s always worth introducing it, but do not be discouraged if they are not overly interested. At minimum, it suggests to them that they can experience a calmer state when they are not “in their mind” with their thoughts.

The main point of learning how to relax the body is to help expand the continuum between being stressed and relaxed. The more children practice how to relax, the easier it will be to return to a state of relaxation. It can also be helpful during E/RP when they have to tolerate the discomfort that comes from not engaging in the compulsion or ritual. It offers something they can do instead of the ritual.

Addressing the Thoughts Component

Addressing the OCD thoughts and learning a variety of strategies to challenge them is one of the most important aspects of treatment. The essential goal is to learn how to identify the OCD thoughts as “symptoms of OCD” and not real thoughts deserving of consideration. When the child can see the OCD as OCD, then he is able to fight it. Because OCD presents itself as regular thoughts, this first step of relabeling it as a symptom of OCD is key. Similarly, learning that thoughts are just thoughts and have no power unless we give them power supports this shift. Let’s go through the various strategies designed to challenge the thoughts.

Loop Recordings

I used to call these “worry tapes” until cassette tapes became obsolete. Of everything out there to treat OCD thoughts, this is by far the most effective strategy. The child lists all of her OCD thoughts and worries, and then we type them up. The thoughts are written exactly how they sound in her head (so she would say, “What if I get sick from touching that?” and would not say, “Sometimes I worry that I’ll get sick”), and then she makes a recording of the thoughts (usually using her phone or a parent’s phone). Once she has a recording of at least 1–2 minutes, she begins to play it back in a row for 10–15 minutes every day. It sounds counterintuitive to do this, and most people worry that by listening to the thoughts over and over in this way, that the OCD will become stronger and the person will become more anxious. However, the total opposite happens: With repetition, the thoughts go from alarming to boring. After hearing herself say the thoughts over and over and over in this deliberate way, she eventually habituates to the thoughts. By hearing herself say the thoughts out loud, the OCD becomes “externalized,” and this makes it easier to see the OCD as something other than herself. The child becomes an “observer” of her thoughts. And then, by listening repeatedly and hearing the thoughts over and over until they become boring and unalarming, she causes the thoughts to lose power. When making the loop recording, the child will often be scared or embarrassed to articulate her worries. Therefore, it is necessary to help normalize this exercise and validate the discomfort that goes into it. I usually say something about how if it’s in her head, it is worth saying it aloud, or that it’s in there anyway, and my office can be an extension of whatever it is that is on her mind.

Uncertainty Training Recordings

This is another version of the loop recording, except that you take the OCD thoughts and convert them to “uncertainty training” thoughts. For example, “What if I get sick from touching that?” becomes “It is always possible that I will get sick from touching that.” The goal is to be able to tolerate not knowing for sure about something—to tolerate uncertainty (Leahy, 2006). OCD creates doubt and, at the same time, makes the person feel that he needs certainty. Checking and rechecking behaviors are performed in service of trying to know something for sure, yet the OCD is never satisfied and instead, the person gets stuck in the cycle of checking. When he learns to tolerate not knowing, and accept being uncertain about it, the cycle becomes irrelevant and the checking pattern is challenged. (And, of course, when this is paired with E/RP, the child practices the trigger on purpose—touching that surface or doorknob without checking it for germs or washing his hands—so the uncertainty training is done both cognitively by hearing the uncertainty training loop and then behaviorally by deliberately not doing the ritual of checking or washing and tolerating the uncertainty that comes from it.) After making a loop recording, I use the same typed list of thoughts and convert them into uncertainty training thoughts. Then I have the child make a recording of this as well, and the practice becomes listening to the loop recording followed by listening to the uncertainty training recording.

Let’s go through an example, using both recordings, with a case already described:

I worry about killing something like by stepping on it. It makes walking around outside very hard and recently, I started wearing soft flip-flops only when I go outside. This way, I can see what’s on the bottom because there are no lines or dents. I look at the bottoms to make sure I didn’t step on an animal or a bug. When I come home I tell my mom about the different times I stepped on something at school that might have been a bug or an animal, and I feel better when she tells me it wasn’t. Sometimes I don’t know if I stepped on a bug or animal, and I go back and check the area. Also, I don’t go on the grass or dirt at recess because I’m pretty sure I’d end up stepping on something and killing it. I also worry about this cat that I’ve seen in our neighborhood and I’m not sure if that cat has a home so I keep putting out a bowl of milk in the back just in case.

—Ali, age 9

Ali’s Loop Recording:

What if I stepped on something and it was a bug or an animal? What if I injured it and now it can’t walk? What if I killed it? What if I stepped on a bug and didn’t know I killed it? I should go back and check to make sure. What if there are little animals on the grass that you can’t see? You can’t see the bugs in the grass. What if that cat dies because I never put milk out?

Ali’s Uncertainty Training Recording:

It is always possible that I stepped on something and that it was a bug or an animal. It is always possible that I injured it and now it can’t walk and it’s all my fault. It is always possible that I killed it. It’s possible that I stepped on a bug and wouldn’t know that I killed it. It’s always possible that if I go back and check I still won’t see it and won’t be able to know for sure. It’s possible that there are little animals on the grass that you can’t see. It’s always possible that the cat will die because I never put milk out.

Ali listened to both recordings back-to-back; together they were a little under 2 minutes. She played the recordings for a total of six times each, which took about 11 minutes, and she did it every day. After 3 weeks, these thoughts no longer bothered her and they no longer occurred randomly, with the exception of a few times in which she was able to move past it quickly and shift her attention onto other things with ease.

The purpose of the loop recordings is to desensitize to the thought itself so the thought is no longer a trigger; the goal is not to desensitize or become okay with the content of the thought. The content of the thought is what they are worried about—the goal is not to accept or be okay with these bad things happening; rather, the goal is to become bored by the thought itself. The goal is to desensitize to the thought itself, regardless of the content. The thought, not the content, is the problem with OCD, as the thought keeps getting repeated over and over. It is important to understand this and also simplifies the treatment in a way, as it means that no matter what the content the thought is about (even if the content changes over time), one can become desensitized to the thought.

With loop and uncertainty training recordings, the child often makes several of them. At first, she’ll have one recording, but then she will realize that other thoughts came up or that there is an area of the OCD she didn’t do a recording on. Usually, she will create 2–3 additional recordings and then listen to all of them together. Once a recording is experienced as unalarming and boring, she can stop listening to that recording and focus on other ones. One important note about the “need to confess” type of OCD: It is important to limit the number of additional recordings the child makes to no more than 5 in total. We want to prevent the recordings from becoming a ritual, as the child may feel that the recordings are allowing her to “confess” or “tell” her thoughts or actions (and if she plays the recordings for you, that may allow her compulsion to happen, so she should have some recordings that you, her parent, never hear).

Positive Self-Talk

Positive self-talk allows your child to replace his OCD thoughts with ones that help to challenge the OCD and prevent compulsions. Unlike loop and uncertainty recordings, which are used at planned times other than during E/RP, self-talk is used during the exposures to help the child be able to cope with doing them. Also, your child should have some favorite self-talk statements that he relies on every day. The following self-talk statements help to reframe your child’s experience with OCD (some are more sophisticated than others, and you can tailor the list to be appropriate for your child’s age):

I must face my fears to overcome them.

I must face my fears to overcome them.

I am uncomfortable, but I can handle it.

I am uncomfortable, but I can handle it.

I’m scared, but I’m safe.

I’m scared, but I’m safe.

In the present moment, I am okay. Everything is fine.

In the present moment, I am okay. Everything is fine.

I can handle feeling anxious and I can handle what my body feels like when I’m anxious, or even sick. I can be okay in any situation.

I can handle feeling anxious and I can handle what my body feels like when I’m anxious, or even sick. I can be okay in any situation.

I can tolerate the discomfort that comes from facing my OCD.

I can tolerate the discomfort that comes from facing my OCD.

Anxiety is not an accurate (or good) predictor of what’s to come. It’s just an unpleasant feeling.

Anxiety is not an accurate (or good) predictor of what’s to come. It’s just an unpleasant feeling.

It’s just the OCD talking. Someone without OCD wouldn’t be having this thought. It’s just an OCD thought.

It’s just the OCD talking. Someone without OCD wouldn’t be having this thought. It’s just an OCD thought.

It’s just the OCD talking, so I don’t need to listen to it.

It’s just the OCD talking, so I don’t need to listen to it.

What would someone without OCD think in this situation? What would they do?

What would someone without OCD think in this situation? What would they do?

It’s me versus the OCD. Each time I listen to the OCD, it becomes stronger, and each time I don’t, I become stronger. I must handle the temporary anxiety that comes when I do not give in.

It’s me versus the OCD. Each time I listen to the OCD, it becomes stronger, and each time I don’t, I become stronger. I must handle the temporary anxiety that comes when I do not give in.

When I give into the anxiety, I am letting it run my life. When I don’t, I regain control and become free to live my life.

When I give into the anxiety, I am letting it run my life. When I don’t, I regain control and become free to live my life.

I cannot let OCD make decisions for me or control my life.

I cannot let OCD make decisions for me or control my life.

I cannot allow OCD to influence my behavior or my family’s behavior.

I cannot allow OCD to influence my behavior or my family’s behavior.

What would someone who is proactive do in this situation?

What would someone who is proactive do in this situation?

What is the proactive thing to do?

What is the proactive thing to do?

I cannot react to the anxiety and let it control my life.

I cannot react to the anxiety and let it control my life.

I’ve never regretted facing my fears.

I’ve never regretted facing my fears.

I’ve never regretted challenging the OCD.

I’ve never regretted challenging the OCD.

Once I prevent the ritual, after a few minutes, the urge is gone and I’m fine. The hardest part is not giving in at first.

Once I prevent the ritual, after a few minutes, the urge is gone and I’m fine. The hardest part is not giving in at first.

Thoughts have no power unless I give them power. Thoughts are just thoughts.

Thoughts have no power unless I give them power. Thoughts are just thoughts.

I can become an observer of my thoughts rather than a participant in them. I can see that it’s “just a thought.”

I can become an observer of my thoughts rather than a participant in them. I can see that it’s “just a thought.”

I have to disconnect from the content of my OCD thoughts. I must see them and label them as a “symptom of OCD” rather than real thoughts deserving of consideration.

I have to disconnect from the content of my OCD thoughts. I must see them and label them as a “symptom of OCD” rather than real thoughts deserving of consideration.

I have to “sit with” and tolerate the discomfort that comes from not giving into the OCD.

I have to “sit with” and tolerate the discomfort that comes from not giving into the OCD.

When I “sit with” and “tolerate” the discomfort, it goes away. Staying with the discomfort allows it to be metabolized.

When I “sit with” and “tolerate” the discomfort, it goes away. Staying with the discomfort allows it to be metabolized.

This is about tolerating negative emotions. I can handle whatever I feel. I don’t need to be overwhelmed by what I feel.

This is about tolerating negative emotions. I can handle whatever I feel. I don’t need to be overwhelmed by what I feel.

I have to tolerate the uncertainty of the situation and how I cannot know for sure. Some uncertainty is part of the normal life experience.

I have to tolerate the uncertainty of the situation and how I cannot know for sure. Some uncertainty is part of the normal life experience.

Courage comes after slaying the dragon. Once I face my fears, I will realize I can do it.

Courage comes after slaying the dragon. Once I face my fears, I will realize I can do it.

The goal is to not let any of these “thoughts” have any power in my life. This is about changing my relationship with my thoughts.

The goal is to not let any of these “thoughts” have any power in my life. This is about changing my relationship with my thoughts.

Once I get good at labeling the thought as OCD and not focusing on the content of the thought, it won’t bother me. I’m not afraid of the thought, and I don’t give it any power.

Once I get good at labeling the thought as OCD and not focusing on the content of the thought, it won’t bother me. I’m not afraid of the thought, and I don’t give it any power.

I have to expect that the thoughts will come up in my trigger situation. Expect it and plan how to respond to it without giving in.

I have to expect that the thoughts will come up in my trigger situation. Expect it and plan how to respond to it without giving in.

What can I do (what action can I take) in this moment to connect with something (an activity, a book, yoga, another person)?

What can I do (what action can I take) in this moment to connect with something (an activity, a book, yoga, another person)?

All of this self-talk is designed to give your child or teen a sense of what to say in response to the OCD. This is how your child can challenge and “talk back” to the OCD, and self-talk can be used during the exposures. Knowing what the OCD sounds like and how it comes up and seeing it as separate from himself make him better able to challenge it.

“Stamping” It OCD

Once I have a sense of the different OCD thoughts the child has, I take a sheet of paper and write several of them down on different parts of the paper, leaving space between each. Then using a red Sharpie marker, I have them “stamp” the OCD thoughts by writing “OCD” over the thought, in big letters. When the thick red ink is written over the thought, it becomes hard to read what it says. Several clients have told me this is very helpful and that when they have a random OCD thought come up, they visualize “stamping” it with a big OCD stamp, enabling them to dismiss it. Once it’s accurately labeled, children can become good at dismissing it. We are not trying to forget about the thought; we are trying to label it so we can dismiss it as irrelevant (and as only a symptom of OCD).

Distraction

In the moments when your child is either too activated to use any of the CBT strategies or when doing E/RP, distraction can be useful, as it helps him refocus temporarily on something else. Then he can return to the E/RP a bit calmer and better able to tolerate the discomfort. For example, a child may have thoughts about something bad happening to a loved one and perform the compulsion of shaking his head or tapping his fingers or doing some concrete behavior, such as washing his hands, in response to the obsessive thought. He learns that this behavior is OCD and that he has to challenge it by not doing the compulsions. Knowing this is the treatment plan may create heightened anxiety about having the bad thoughts. Therefore, before he can do the challenge, he may need to do a little distraction first. Generally, we want distraction to be used momentarily, with the goal of doing the real OCD work once he has calmed down a bit. Distraction occupies the mind and gives the body the chance to slow down and be calmer. Here are some distraction techniques:

Use the ABCs to make lists: girls’ names (Alicia, Bonnie, Camryn, Denise, Emily) or boys’ names; fruit/veggies (Apple, Banana, Carrot, Date, Eggplant); cities/states/countries (Africa, Bethesda, Cuba, Delaware, Ethiopia); and so on. If the child is younger, she can just make a list for a category, without it being alphabetical.

Use the ABCs to make lists: girls’ names (Alicia, Bonnie, Camryn, Denise, Emily) or boys’ names; fruit/veggies (Apple, Banana, Carrot, Date, Eggplant); cities/states/countries (Africa, Bethesda, Cuba, Delaware, Ethiopia); and so on. If the child is younger, she can just make a list for a category, without it being alphabetical.

Lists of Five: five things that are green, five things in my backpack, five favorite books, five favorite musicians, etc.

Lists of Five: five things that are green, five things in my backpack, five favorite books, five favorite musicians, etc.

Playing a game or doing a puzzle such as a word search.

Playing a game or doing a puzzle such as a word search.

The distraction techniques should be easy to access and not require much in terms of effort or materials. Again, they are using it for just a short time period before doing the hard work of challenging the OCD. The reason for this is that we want your child to learn how to handle and tolerate the discomfort that comes from not engaging with OCD or its rituals. Avoiding the uncomfortable feelings is another form of avoidance and won’t allow her to truly overcome the OCD. She has to be able to tolerate the unpleasant emotions, such as the anxiety, and habituate to those feelings in order to not get triggered emotionally anymore.

When looking at the techniques described thus far, it may be a bit confusing about how they are used and fit together, and also how to negotiate the natural contradictions of, for example, uncertainty training and self-talk. Essentially, all of these strategies should be learned, as they each have their place at certain times:

Loop recordings and uncertainty training recordings are part of planned practices (“homework,” if you will) that the child does to desensitize to his OCD thoughts and intolerance of uncertainty. When practicing the recordings, the child should find a time when he is not currently being triggered by the OCD, if possible. Usually done at home, he finds 10–15 minutes a day to sit down and listen to the loop over and over; after 2–4 weeks, he should desensitize to the recordings and find them boring instead of anxiety-provoking. You may need to sit with him at first to get him used to it and to help him deal with the anxiety that surfaces from hearing the OCD thoughts (again, for the “need to confess” type, make sure that they have at least one recording that you never hear). The overarching goal of the recordings is to be okay with the upsetting or anxiety-producing thoughts or uncertainty.

Loop recordings and uncertainty training recordings are part of planned practices (“homework,” if you will) that the child does to desensitize to his OCD thoughts and intolerance of uncertainty. When practicing the recordings, the child should find a time when he is not currently being triggered by the OCD, if possible. Usually done at home, he finds 10–15 minutes a day to sit down and listen to the loop over and over; after 2–4 weeks, he should desensitize to the recordings and find them boring instead of anxiety-provoking. You may need to sit with him at first to get him used to it and to help him deal with the anxiety that surfaces from hearing the OCD thoughts (again, for the “need to confess” type, make sure that they have at least one recording that you never hear). The overarching goal of the recordings is to be okay with the upsetting or anxiety-producing thoughts or uncertainty.

Positive self-talk, on the other hand, is to be learned (and often memorized) during calm moments, but used during anxious ones, such as when doing E/RP. During the E/RP, the child says to herself something like, “I must face my fears. It’s just the OCD talking, and I don’t have to listen. It’s just a thought, and thoughts have no power.” Saying the self-talk allows her to be able to do the E/RP and face her fears without doing the compulsions. The self-talk, then, supports her and encourages her to manage the experience and make the necessary progress.

Positive self-talk, on the other hand, is to be learned (and often memorized) during calm moments, but used during anxious ones, such as when doing E/RP. During the E/RP, the child says to herself something like, “I must face my fears. It’s just the OCD talking, and I don’t have to listen. It’s just a thought, and thoughts have no power.” Saying the self-talk allows her to be able to do the E/RP and face her fears without doing the compulsions. The self-talk, then, supports her and encourages her to manage the experience and make the necessary progress.

“Stamping” the OCD should be introduced as an activity first. Then when the thoughts come up automatically, the child should either visualize stamping it or actually write it down and “stamp” it as “OCD.” If OCD thoughts come up and your child is telling you about them, you can prompt the strategy by starting to write the thoughts down. Then give your child a red marker to have her write over the OCD thoughts with a big “OCD” in red ink. Again, this may be done at random times and either during or not during E/RP.

“Stamping” the OCD should be introduced as an activity first. Then when the thoughts come up automatically, the child should either visualize stamping it or actually write it down and “stamp” it as “OCD.” If OCD thoughts come up and your child is telling you about them, you can prompt the strategy by starting to write the thoughts down. Then give your child a red marker to have her write over the OCD thoughts with a big “OCD” in red ink. Again, this may be done at random times and either during or not during E/RP.

Distraction, as explained above, is to be used temporarily to help him calm down or manage the anxiety that comes from doing the exposures. Once he feels stronger or calmer, then he can and should face the OCD head-on.

Distraction, as explained above, is to be used temporarily to help him calm down or manage the anxiety that comes from doing the exposures. Once he feels stronger or calmer, then he can and should face the OCD head-on.

Identify and Challenge Cognitive Distortions (Thinking Errors)

In addition to the common themes of OCD (overimportance of thoughts, desire for certainty), most people with OCD make several thinking errors. Identifying thinking errors is another step in challenging the OCD and making the OCD thoughts lose credibility. Here are the most typical thinking errors of OCD:

All-or-nothing thinking. Thinking in extremes, meaning that things are either perfect or a failure; there is no middle ground—it’s either one extreme or another. This inflexible style of thinking is often seen in perfectionism, where things have to be exactly as the person wants them to be and thinks they should be (and she can keep repeating and fixing until they are “right”), or else she is frustrated, anxious, or will avoid the activity or whatever it is that she sees as imperfect. It can also come up with cleanliness and germs, where the person is extreme about cleaning or sees an entire building as contaminated, instead of just one part (e.g., the bathrooms).

All-or-nothing thinking. Thinking in extremes, meaning that things are either perfect or a failure; there is no middle ground—it’s either one extreme or another. This inflexible style of thinking is often seen in perfectionism, where things have to be exactly as the person wants them to be and thinks they should be (and she can keep repeating and fixing until they are “right”), or else she is frustrated, anxious, or will avoid the activity or whatever it is that she sees as imperfect. It can also come up with cleanliness and germs, where the person is extreme about cleaning or sees an entire building as contaminated, instead of just one part (e.g., the bathrooms).

Catastrophizing. Visualizing the worst-case scenario and thinking the worst is going to happen. This typically comes out as “What if . . .” thinking. The child may hear of a risk and overestimate the severity of it and the likelihood of it happening. For example, a child may hear that someone got hurt while skiing and then worry that she or a loved one will also get a head injury and become brain damaged when skiing. This thinking error creates a lot of avoidance and overreactive behavior.

Catastrophizing. Visualizing the worst-case scenario and thinking the worst is going to happen. This typically comes out as “What if . . .” thinking. The child may hear of a risk and overestimate the severity of it and the likelihood of it happening. For example, a child may hear that someone got hurt while skiing and then worry that she or a loved one will also get a head injury and become brain damaged when skiing. This thinking error creates a lot of avoidance and overreactive behavior.

Selective attention. Paying attention to certain information that confirms one’s belief while ignoring evidence that contradicts the belief. The child may think that eating meat can cause you to die, citing examples of a few outbreaks of E. coli where a few people died; however, she won’t consider how many people eat meat every day and are fine.

Selective attention. Paying attention to certain information that confirms one’s belief while ignoring evidence that contradicts the belief. The child may think that eating meat can cause you to die, citing examples of a few outbreaks of E. coli where a few people died; however, she won’t consider how many people eat meat every day and are fine.

Shoulds. Making rules about how things should be. With OCD, these rules tend to be exaggerated and very strict; for example, “I should not pray for my family at the same time as when I’m praying for someone who is sick.”

Shoulds. Making rules about how things should be. With OCD, these rules tend to be exaggerated and very strict; for example, “I should not pray for my family at the same time as when I’m praying for someone who is sick.”

Magical thinking. Thinking some things, such as numbers, are lucky, while other things are unlucky. The person may do things in “fours,” such as picking the fourth tissue or the fourth book in the row. She may see something as a bad sign or bad luck and then avoid it because of that belief.

Magical thinking. Thinking some things, such as numbers, are lucky, while other things are unlucky. The person may do things in “fours,” such as picking the fourth tissue or the fourth book in the row. She may see something as a bad sign or bad luck and then avoid it because of that belief.

Superstitious thinking. Thinking that by doing something, you will cause or prevent something from happening. For example, the person may tap each foot twice and feel that it will keep his family safe, or he may touch every surface in the room with the belief that it will lead to a good outcome or prevent a bad one.

Superstitious thinking. Thinking that by doing something, you will cause or prevent something from happening. For example, the person may tap each foot twice and feel that it will keep his family safe, or he may touch every surface in the room with the belief that it will lead to a good outcome or prevent a bad one.

Thought-action fusion. The child believes that if he has a thought or an urge to do something, then it will cause him to do it. For example, he will believe that thinking about hurting a sibling will cause him to do to it, and then he won’t trust himself to be alone with his sibling. Or that just thinking about not turning off the oven means he will end up leaving it on, which will end up starting a fire.

Thought-action fusion. The child believes that if he has a thought or an urge to do something, then it will cause him to do it. For example, he will believe that thinking about hurting a sibling will cause him to do to it, and then he won’t trust himself to be alone with his sibling. Or that just thinking about not turning off the oven means he will end up leaving it on, which will end up starting a fire.

Thought-event fusion. The child believes that if he has a thought about something happening, then it will cause it to happen or means it already happened. One example of this may be a child having the image of stepping on an animal, then thinking this image means it happened and that he needs to go back and check.

Thought-event fusion. The child believes that if he has a thought about something happening, then it will cause it to happen or means it already happened. One example of this may be a child having the image of stepping on an animal, then thinking this image means it happened and that he needs to go back and check.

In challenging the thinking errors, the child should learn which ones he uses most often and then come up with a new way of thinking in response. The goal is also for the child to eventually minimize the automatic thought by saying, for example, “Oh, there I go again, catastrophizing.” With repeated practice of challenging the thinking errors and developing new behaviors in response to triggers, the brain learns new associations (and old associations get replaced, becoming obsolete). Basically, the thinking errors are like habits, and the child needs to learn new habits (new associations). As your child’s parent, you can point out when you make thinking errors to normalize it and model being open to coming up with new, more flexible ways of seeing a situation (many of us do all-or-nothing thinking). The self-talk statement of “what would someone without OCD (or anxiety) think in this situation?” is a great way of minimizing the thinking error’s validity.

Metacognitive Therapy

Metacognitive therapy (MCT), developed by Dr. Adrian Wells (2011), is a type of cognitive therapy that offers a great deal to those with OCD. There are two main techniques of MCT: one you want to know about and use with your child (detached mindfulness) and the other (attention training technique) that you should know exists as a potential resource if needed.

Detached mindfulness. This strategy is designed to change one’s relationship with his thoughts. It teaches your child how to become aware (or mindful) of and separate (or detached) from his thoughts. The goal is to learn how to become an observer of one’s thoughts, rather than a participant in them. When you can see the thought as “just a thought” and nothing else, and also remind yourself that thoughts have no power unless you give them power, it allows for a different experience of the thoughts. It also makes it easier to not focus on the actual content of the thought and instead see the thought as a symptom of OCD. When your child “participates” in the thoughts, he gives the thoughts attention, credibility, and value, and engages in behaviors in response to them. When he switches into “observer” mode, he can see the thoughts as they are, without reacting to the actual content of the thought (therefore, no participation). This is how he will change his relationship with his thoughts (so the thoughts don’t have any power). The purpose of detached mindfulness is to help your child reclassify, or recategorize, the OCD thoughts as “symptoms of OCD” rather than real thoughts deserving of consideration.

So, how can your child learn detached mindfulness? The method I use is to write 10 different thoughts on 10 different sheets of paper. Of the 10 thoughts, seven are neutral, nonanxiety-provoking/non-OCD thoughts (N), two are OCD thoughts (OCD), and one is an untrue thought (U). I mix them together, putting them in the following order: N, N, N, OCD, N, N, U, N, OCD, N. Here is an example of 10 thoughts in sequence:

1.My favorite season is summer. I love the feeling of being at camp. (N)

2.I can’t wait to have winter break—we are going to Florida, and I’m so excited. (N)

3.I love the pizza at Pizza CS—it’s so delicious! (N)

4.What if that cupcake has dirty germs and makes me sick and I throw up? (OCD)

5.I’m thinking of joining the environmental club at school. (N)

6.I hope to move up to my next belt in Tae Kwon Do this month. (N)

7.I’m wearing neon yellow socks. (U)

8.I love my brother—we have so much fun playing together. (N)

9.What if I got the flu from sitting next to that girl whose sister had the flu, and now it’s on my clothes? (OCD)

10.Art is so much fun—the teacher really comes up with great projects. (N)

After the 10 thoughts are written and organized in the order outlined, I have the child read the 10 thoughts three times in a row (quickly) and then say aloud: “I can see these are just thoughts. Whether they are true or not, anxiety-provoking or not, they are just thoughts. Thoughts have no power unless I give them power.” The child then practices this 1–2 times a day every day for a few weeks, depending on the severity of the OCD (sometimes he will do it for longer). At any point, he can substitute the OCD thoughts for different ones to keep it current (if the thought he wrote down is no longer a trigger, for example). With practice, this will help your child become an observer of the thoughts and learn to not respond to them. He doesn’t have to fear the thoughts anymore. Also, the content becomes less relevant, because he sees that all of the thoughts have the common element of being thoughts, so the specifics are not important. A 13-year-old with severe OCD with whom I worked practiced this technique and had the greatest feedback, demonstrating his mastery. He said: “I think I got it. Now, when the terrible thoughts come up, I see them as if they are being typed out on a screen in front of me; I cannot really read them or know them, but I see it as just the OCD and it doesn’t bother me anymore.” This is the goal!

Attention training technique. This is the second of the MCT techniques that I use, and due to its time-intensive nature, I tend to use it as a last resort. However, I have found it to be extremely helpful, and it is also well-supported by research. Attention training technique (ATT) is a 12-minute audio recording that is listened to while staring at a dot on the wall; ideally, the child or teen listens to the 12-minute long practice twice a day. The audio recording script (which is printed in Dr. Wells’s book Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression and also found on the MCT Institute website; see references) instructs the child to focus on different sounds, then to switch his attention from one sound to another, and then to count all the sounds he hears at the same time (during which all of the previous sounds occur at the same time). With repeated listening, your child is trained to easily switch from one thought (sound) to another, which addresses the common problem of being stuck, or locked into, a thought. Dr. Wells (2011) considered OCD to be a “cognitive attentional syndrome” in which the person’s attention gets stuck on an unwanted or anxiety-inducing thought. The techniques of MCT have the goal of getting the person unstuck and free from the cycle of rumination.

Understanding the OCD Cycle

In addition to all of these techniques to help with the thoughts component, it is important for the child to gain a thorough understanding of the OCD cycle. Understanding the cycle will help her to externalize the OCD and lead to greater awareness of the OCD. As you see her getting triggered and performing the rituals, it can help to point out and even write out the cycle so she can gain more insight into the pattern. For instance, you can discuss the trigger, her interpretation or thought, how she felt, and what she did in response.

Addressing the Behavior Component

The behavioral manifestations of OCD include compulsions, rituals, and avoidance behavior. Additionally, children with OCD often seek reassurance (usually from a parent or caregiver) and ask a lot of questions. If the child with OCD is unable to avoid a trigger, he will endure it with quite a bit of distress and may do a compensatory ritual later on. If unable to perform a compulsion, he may become agitated.

Compulsions and rituals can be obvious or subtle. Most parents are surprised to discover the extent of the compulsions and how much mental space they occupy for the child. When learning the OCD cycle, the child sees the connection between triggers, thoughts, anxiety, and rituals (compulsions). The compulsions are typically performed in response to an obsessive thought, image, or urge, and they offer immediate relief for your child. This immediate relief ends up ensuring long-term OCD (so it’s short-term relief, long-term OCD). A primary goal in therapy is for your child to understand that when the compulsion is prevented, the immediate relief is replaced with short-term anxiety; however, with regular practice of preventing the compulsion, the child overcomes the OCD. So short-term relief is traded for long-term relief and success. It’s traded for freedom. This is important because the child will need to have a rationalization to rely on for why she is going to purposely cause anxiety and discomfort for herself. Tolerating the discomfort is the key and is necessary for success; it’s about facing your fears and staying with it, despite the unpleasant experience.

It is important for children and teens to understand the face your fears mindset and why it is a necessary part of the treatment process. The compulsions, rituals, and avoidance all strengthen the OCD. When your child learns to adopt the “face your fears” mindset, and understands that it is “me versus OCD,” he can start to challenge these behaviors. Exposure/Response Prevention is the choice strategy to helping the child with OCD. This is the “facing your fears” part, and it involves purposely exposing the child to a trigger situation and then teaching him how to prevent doing the ritual or compulsive behavior. An important principle to keep in mind when doing E/RP is something I borrow from a type of therapy called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)—the “acceptance” part, which means

opening up and making room for painful feelings, sensations, urges, and emotions. We drop the struggle with them, give them some breathing space, and allow them to be as they are. Instead of fighting them, resisting them, running from them, of getting overwhelmed by them, we open up to them and let them be. (Harris, 2009, p. 9–10)

The child has to learn how to “sit with” and tolerate the discomfort that comes from not performing the rituals or typical response to the trigger. Learning how to deal with the uncomfortable feelings, and seeing that after a while, the anxiety goes down and the urge to perform the ritual goes away, is a necessary component. Habituation occurs when the child stays in the situation long enough to get used to it. This is why the practices should gradually build up to being longer in duration, so the habituation happens. The child also needs to be able to realize that she can actually prevent herself from doing the ritual and that she is capable of facing her fears. It is not until she learns how to face her fears and tolerate the resulting anxiety that she will have the confidence to do so again and again (remember, courage comes after slaying the dragon). This is a boost to her self-esteem and a real triumph over the self-doubt that results from the OCD and is how she will overcome it.

To start, I have the child list her trigger situations, and I convert them into specific practices. For example, a trigger might be using public bathrooms, so the specific practice would be “walk into a public bathroom and touch the faucet with your hands.” Once we have created a list of as many trigger situations, she can come up with, she puts them in order from easiest to hardest. I will have her look at the list and say “Okay, which is the easiest one to do?” and she will put a “1” next to it, then “Which is the hardest one on this list? The one you couldn’t imagine doing?” and for a list of 22 items, she will put a “22” next to that one. Then she goes from there, ordering each item with a number in between. Using the list, we create a “ladder”: On a poster board, I draw a ladder with rungs and write each situation on a step, with the easiest one at the bottom and the hardest one at the top. As she starts facing her fears, I put stickers on the ladder (up to two for each step: one on the left side once she has practiced that step once, and a second sticker on the right side once she has mastered the step from repeated exposure and it has now become part of her normal repertoire of behavior). This tracks her progress and rewards her success. (By the way, I use stickers with my adult clients as well, so I consider it an “all ages” practice.)

The following is a sample of a ladder (again using Ali’s case of OCD); the hardest items are on the top and easiest ones are on the bottom:

| (top) | Wear boots and walk on the grass/dirt without going back to check if you stepped on a bug or animal. |

| Wear flip-flops and walk on the grass/dirt without going back to check if you stepped on a bug or animal. | |

| Wear boots and walk on the grass/dirt after seeing a bug in the grass without checking the bottoms afterward. | |

| Wear boots and walk on the grass/dirt without checking the bottoms. | |

| Wear boots and walk on the grass/dirt (can check bottoms). | |

| Wear boots when walking outside without checking the bottoms. | |

| Wear boots when walking outside (can check bottoms). | |

| Wear flip-flops and walk on the grass/dirt without checking the bottoms afterward. | |

| Wear flip-flops and walk on the grass/dirt (can check bottoms). | |

| Don’t put milk out for the cat. | |

| Put milk out for the cat once a week. | |

| Put milk out for the cat every 3–4 days. | |

| Put milk out for the cat every other day. | |

| (bottom) | Come home and don’t tell Mom about anything you stepped on or where you walked. |

You will notice that we broke larger steps into smaller ones, all of which made the exposure work possible and manageable for Ali. I also reminded her that we would go at her own pace, and as long as we were moving forward by doing some practice, she would make progress. I tend to gently push my clients to work on the steps and do as many of them as possible. With Ali’s case, we did all of the exposures together, except for not telling her mother and the ones involving the cat. And to help prepare her for not telling her mom, we made a recording of about 3 minutes of her talking about her day at school and what she was looking forward to at school, none of which involved talking about where she stepped or walked. Her mom played this recording once Ali got in the car for the drive home from school; this allowed Ali to disrupt the ritual and replace it with a different dialogue. She used self-talk cards to help with doing the cat practices. By doing the other steps with her, I was able to help her manage the discomfort and prompt her to think differently about the OCD. In addition, my presence increased her sense of accountability to do the steps, and I was able to remind her of the value of doing the E/RP in the moment.

There are three keys to facing one’s fears: repetition, frequency, and prolonged time. The child repeats each step over and over until he masters it; the practices should occur frequently together (every day if possible); and the child needs to stay in the situation for a prolonged period of time for habituation to occur.

There are a few additional mindsets that can be helpful to offer children as they are doing the exposures. First, I like to talk about the concept from the well-known childhood story We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, where the father and his children travel through obstacles, and for each one, there is no way out but through: “We can’t go over it. We can’t go under it. Oh no! We’ve got to go through it!” (Rosen & Oxenbury, 1997, pg. 2). This echoes the “acceptance” part of tolerating the discomfort and reinforces the idea that the only way to get out of OCD is to actually go through facing one’s fears. Second, I like to explain the difference between being proactive and reactive; in the 2014 book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens by Sean Covey (the son of Stephen Covey, who wrote The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People)—a book I often recommend to clients 12 and up—it is explained that reactive people make decisions based on how they feel, while proactive people make decisions based on their values. OCD, by nature, encourages children to be reactive: They make decisions and their behavior is based upon their feelings (anxiety, uneasiness, discomfort, sense of doom). When we help them identify with the value of overcoming OCD and being liberated from its control, they can use that to guide their behavior. Facing one’s fear is being proactive. You can offer up a simple analogy to explain proactive and reactive: When it comes to homework, your child may not feel like doing it, and if he skips it, then he will have been reactive because he let his feelings decide. However, if he recognizes that he doesn’t feel like doing his homework, but really values coming to school the next day prepared and showing respect to his teachers, etc., then he will do the homework even though he doesn’t feel like it. In other words, the feelings are still there, but they don’t decide or influence the behavior; the child isn’t organized by his feelings. The behavior and the decision of what to do is guided by the person’s values. For the child with OCD, we want to him to value overcoming it and becoming free of its control over his life. Third and lastly, I like to think about giving in or not giving in to the rituals as accumulating savings in a bank account. Each time the child does a ritual, he uses some of the savings, and this also results in not adding more money to the account. Each time he prevents a ritual, he preserves the money. Each time he purposely faces his fears and does E/RP practice, he adds more money to the account. So, there is merit in not giving in and even more merit to practicing on purpose. For some kids, it’s useful for them to see it this way, and this can help them be more committed to not doing the rituals. Also, sometimes they aren’t ready to fully face their fears but were able to prevent a ritual, and we want them to feel good about this and see it as an accomplishment. They might feel that they weren’t able to do an exposure, but they still did something hard by not doing the ritual (they preserved the money).

Another important factor in working with the behavioral component is helping the child find the right balance when it comes to something that may be a ritual but is also something she still has to do. For example, when it comes to handwashing, the child with OCD who has excessive handwashing (typically resulting in dry, cracked skin) still needs to wash her hands every day. She can’t completely avoid washing her hands, yet she almost can’t trust her own judgment about when it’s appropriate to wash, because it is too heavily influenced by the OCD. In this case, we want to give the child clear rules and set times when she should wash her hands, and help her to only wash her hands at those times. So, it might be that she only washes her hands before meals and after she uses the bathroom. (At the same time that she is learning these guidelines, she is also doing E/RP focused on handwashing: She may have steps on eating with unwashed hands, using the bathroom and only quickly rinsing with water, or using a portable toilet and not washing hands at all afterward.) But the guidelines of when to wash her hands on a day-to-day basis should reflect what “someone without OCD would do,” and it should never result in dry, cracked skin.

Another example is the child who has food allergies but also OCD; he has a similar dilemma in that he needs to engage in avoidance behaviors for his health and safety—he cannot touch nuts, for example—yet it may be extreme in that he won’t touch a countertop that was touched by someone who had eaten a handful of nuts yet has no nut pieces on it. The fear of surfaces and doorknobs that he worries may have been touched with nuts will mostly likely never result in an allergic reaction (always check with an allergist first, of course, but from my multiple collaborations with allergists and from having a son with nut allergies, I have been informed that these rather benign behaviors typically never result in a contamination). The balance here, again, is that he has to avoid contamination with his allergen, but he doesn’t have to avoid being around someone who has eaten nuts, or touched a surface after handling nuts, for example.

Finally, an essential part of addressing the behavioral part of OCD is working to eliminate accommodations made by family members. The goal is to integrate steps to reduce and eventually stop family accommodations into the ladder. For example, there could be steps to challenge a rigid bedtime routine of saying, “I love you” in a certain way, and the parent receives guidance on how to modify the routine. We will focus specifically on family accommodations in Chapter 6.

We’ve now gone through the treatment protocol for overcoming OCD. Again, this is all based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is solidly supported by research as the best and most effective approach for treating OCD. In addition to these techniques, there are also pharmacological options. I prefer that a child or teen receive a proper course of CBT before considering medication; however, many children are prescribed medication as a place to start. The most common medications used to treat OCD are SSRIs (such as Prozac and Zoloft). Benzodiazepines and antipsychotics may also be used. More information on medication options, including those used for PANDAS/PANS, is discussed in Chapter 5.