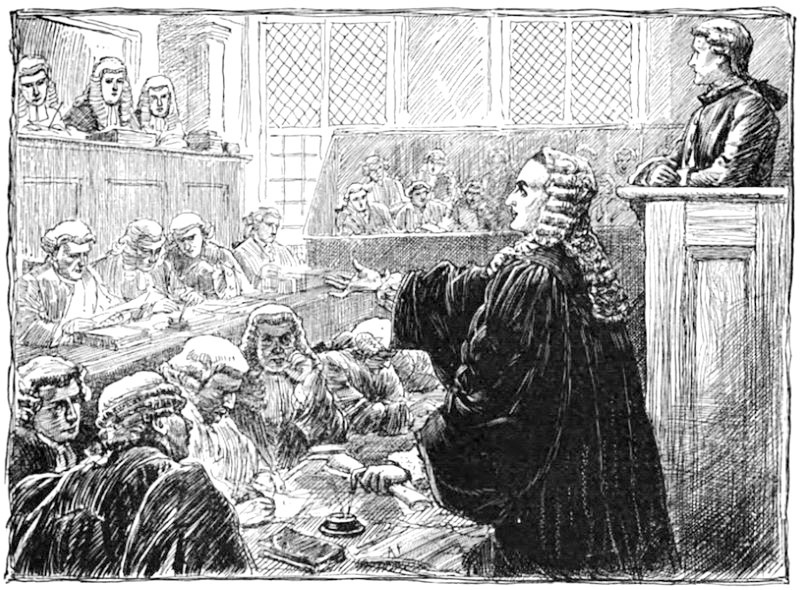

Andrew Hamilton, the attorney for John Peter Zenger, convinced a jury in New York in 1735 to rebel against the oppressive law of seditious libel and free the printer from jail. Their decision contributed to a broad recognition decades later that new safeguards were needed to protect press freedom.

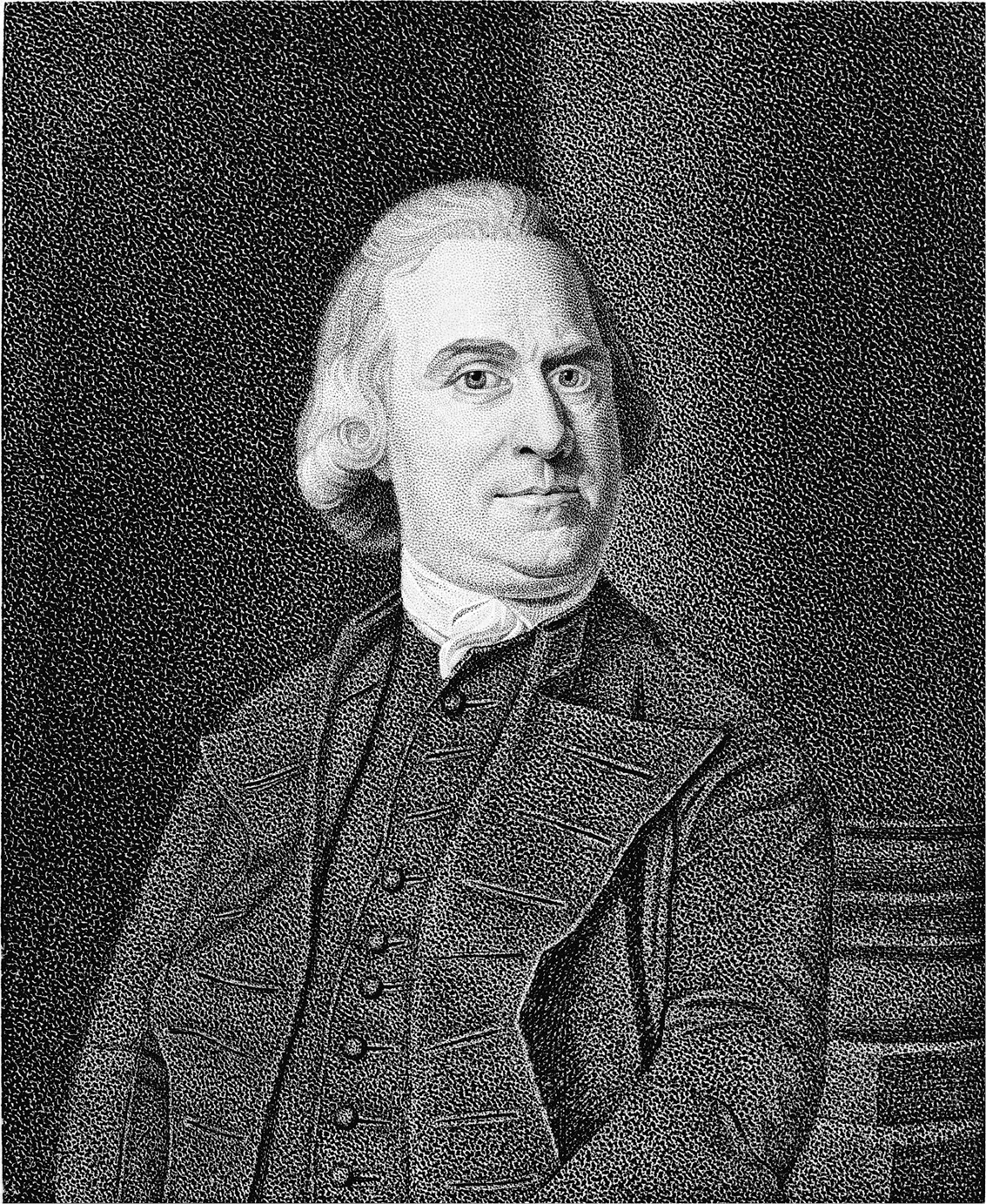

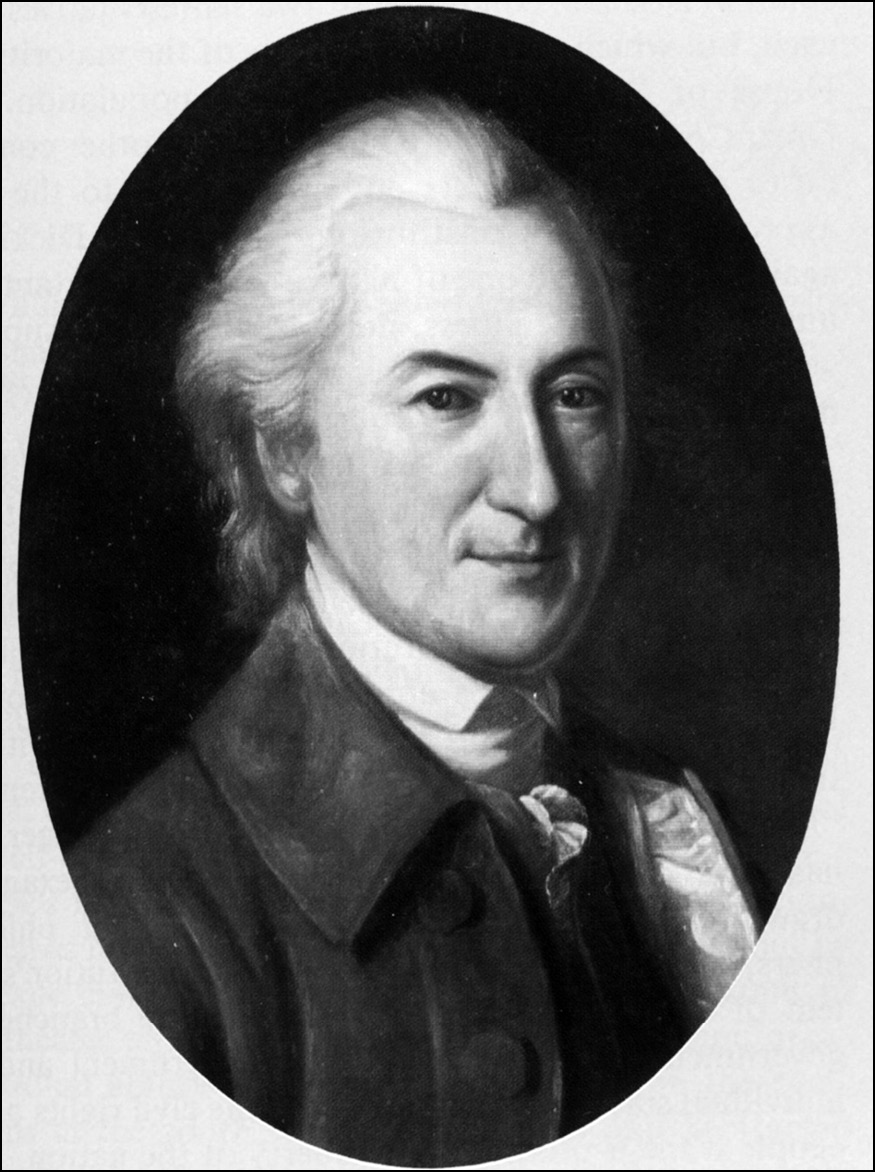

Samuel Adams helped organize resistance in Boston to onerous British regulations. He wrote patriotic letters and essays, some in the radical Boston Gazette, under numerous pseudonyms. (Charles Goodman, engraver, from a portrait by John Singleton Copley / Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

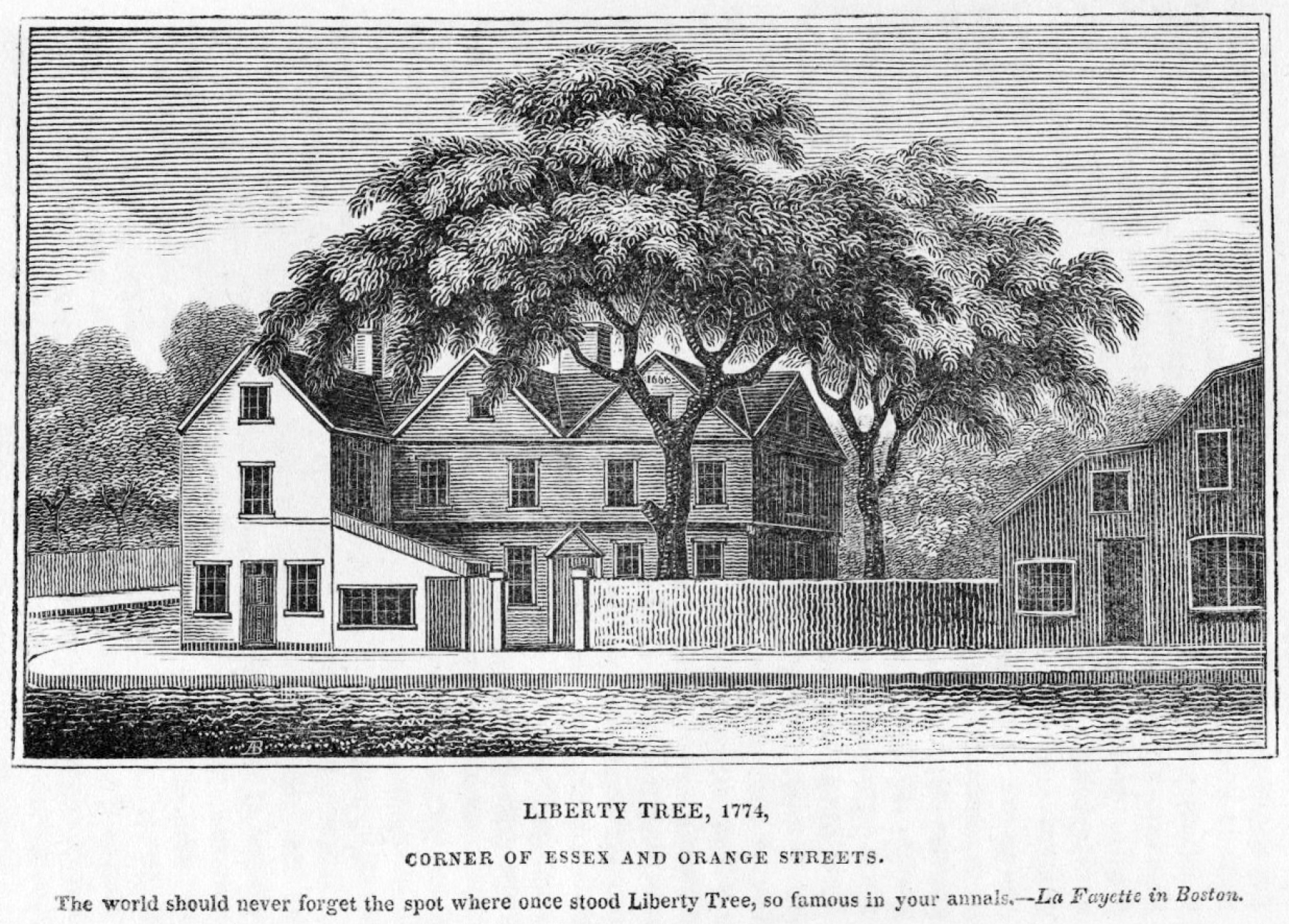

The Liberty Tree on the main road into Boston became the rallying point for loud demonstrations—often including effigies hanging from branches—against British regulations imposed on the colonies. The use of liberty trees and liberty poles spread throughout the colonies, part of an outpouring of symbolic speech that enlarged the public sphere of political expression. (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

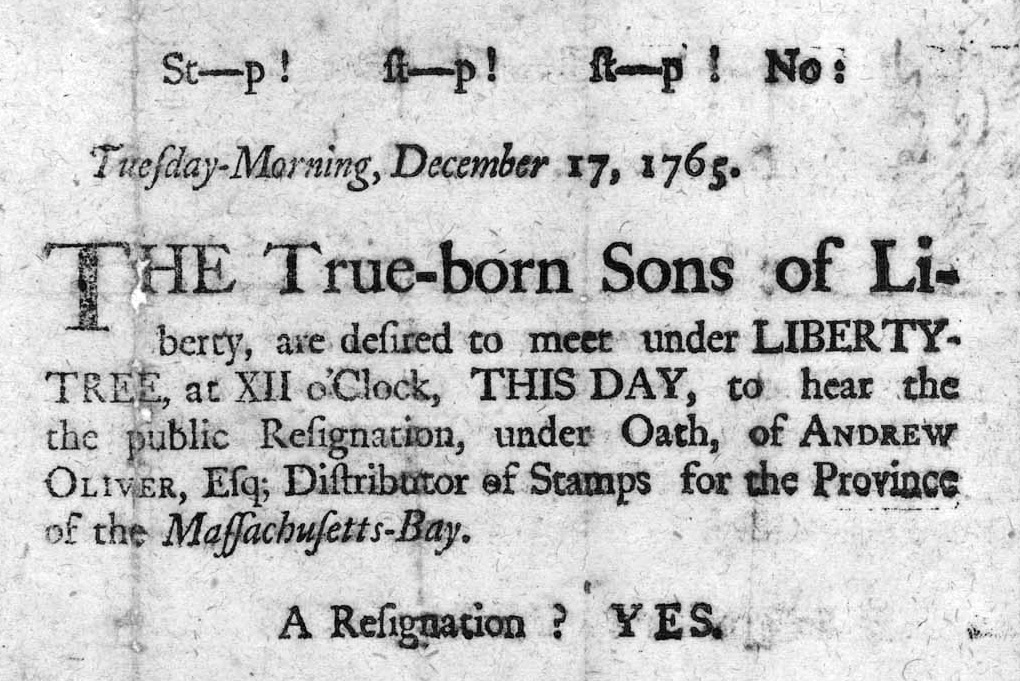

Distributed throughout Boston, this broadside called people to the Liberty Tree on December 17, 1765, to hear the besieged stamp distributor renounce his appointment. (Massachusetts Historical Society)

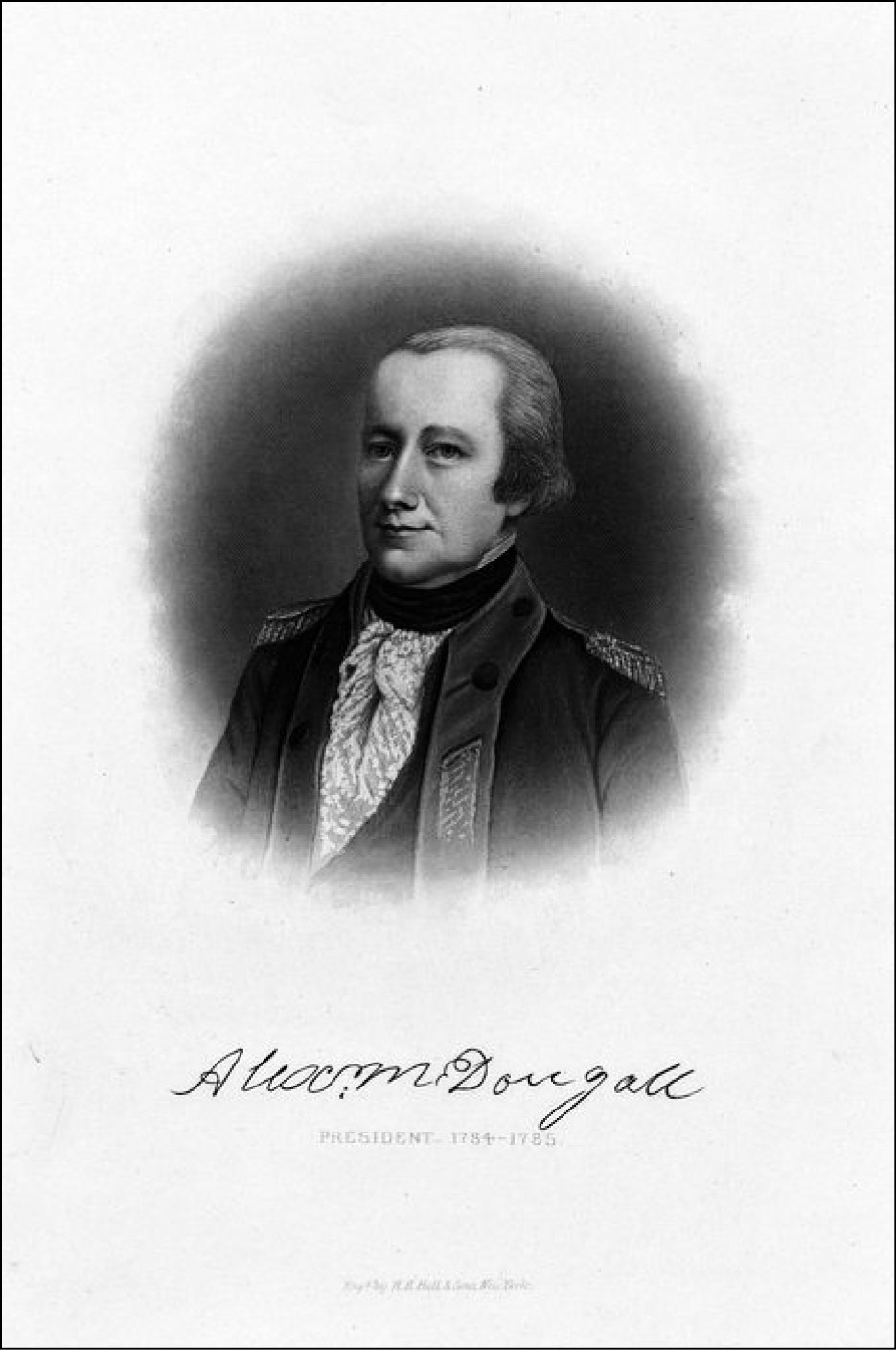

Alexander McDougall, a New York merchant, was jailed on seditious libel charges. The Sons of Liberty orchestrated a campaign that made him famous throughout the colonies as a martyr for press freedom. (Engraved by H. P. Hall and Sons / Courtesy of Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library)

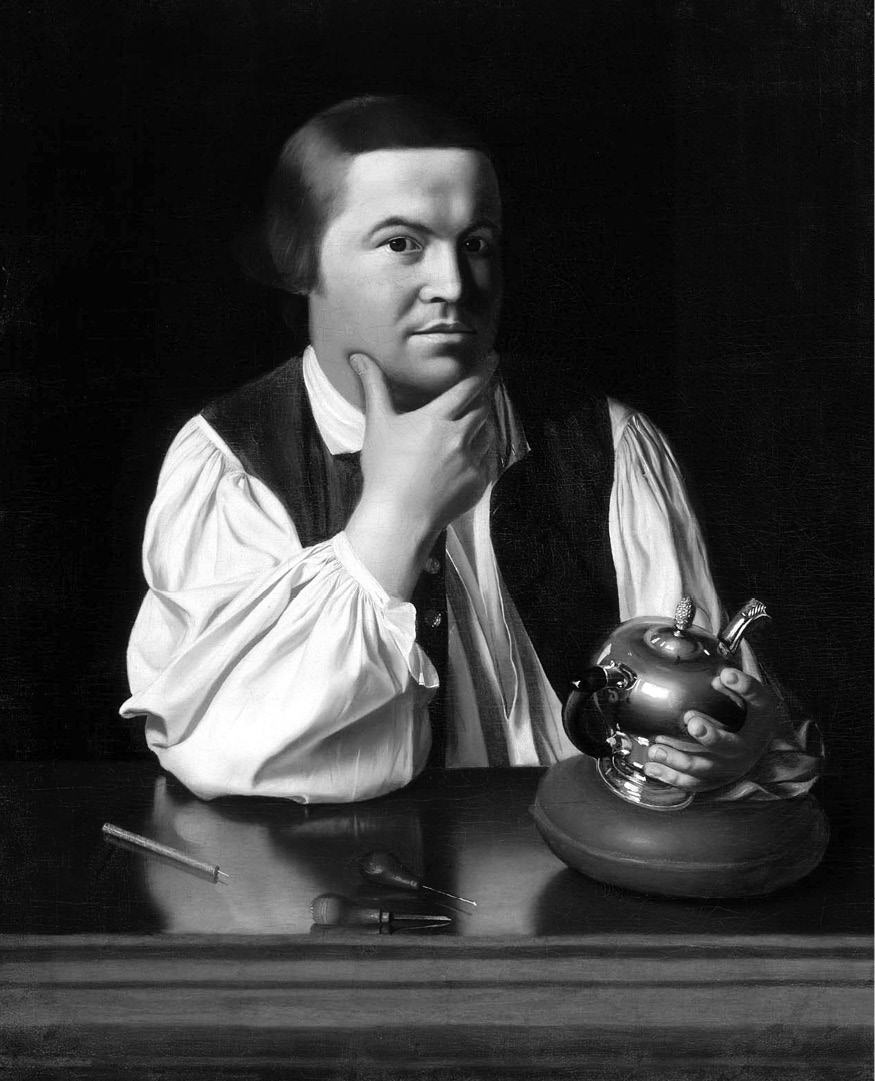

Paul Revere lent his skills as an engraver to the patriot cause and produced illustrations that were more powerful as political commentary than many written works. They reached the public through newspapers and broadsides. (Portrait by John Singleton Copley / Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

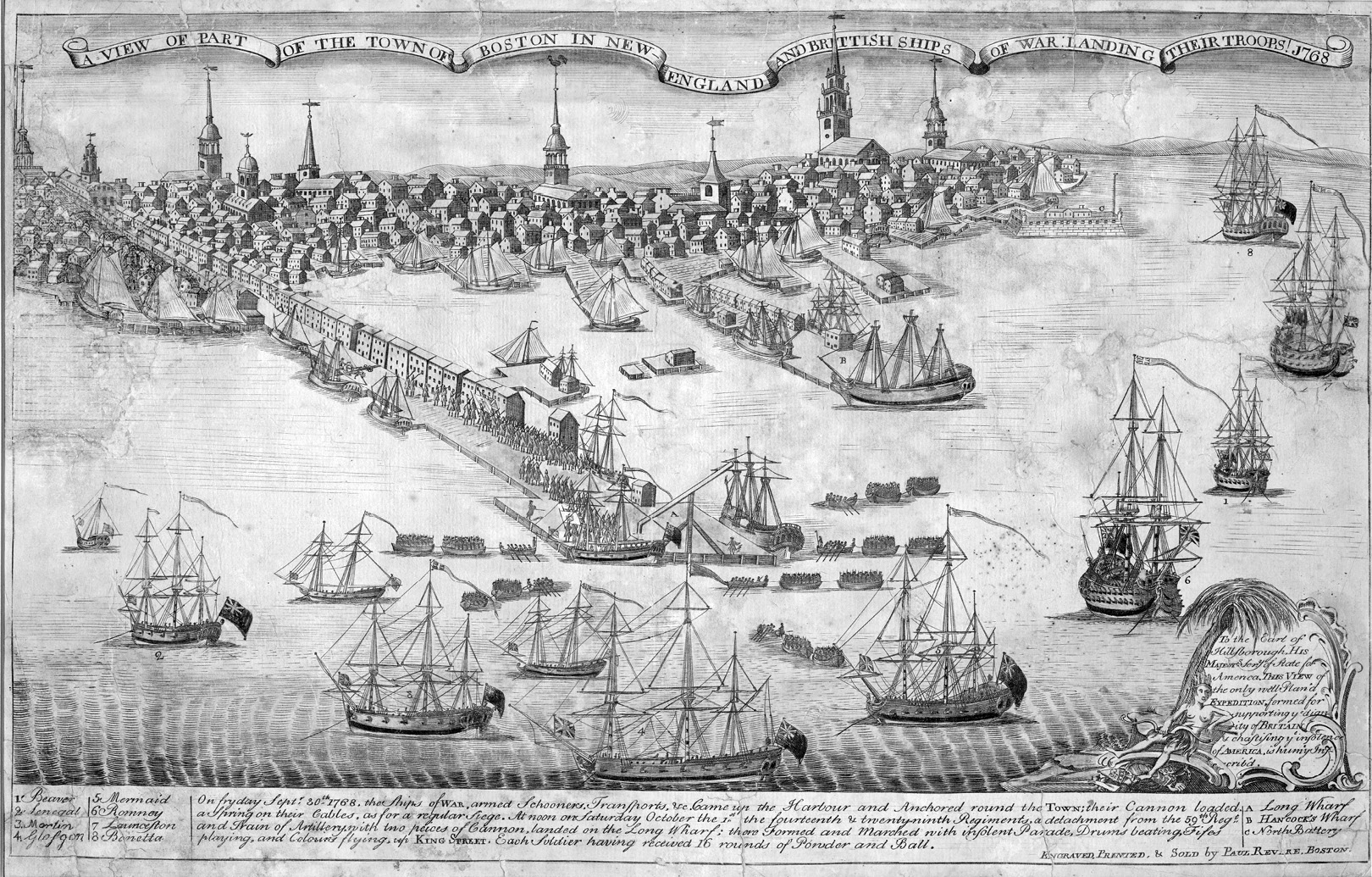

Paul Revere’s three engravings expressed his narrative of British oppression—military occupation (above) leading inevitably to a bloody confrontation and the deaths of civilians (following pages). Here, Revere depicted powerful British warships in 1768 overwhelming Boston, portrayed as a sleepy, innocent town dominated by church steeples. British soldiers are shown landing in the town to begin an occupation that culminated in the Boston Massacre. (American Antiquarian Society)

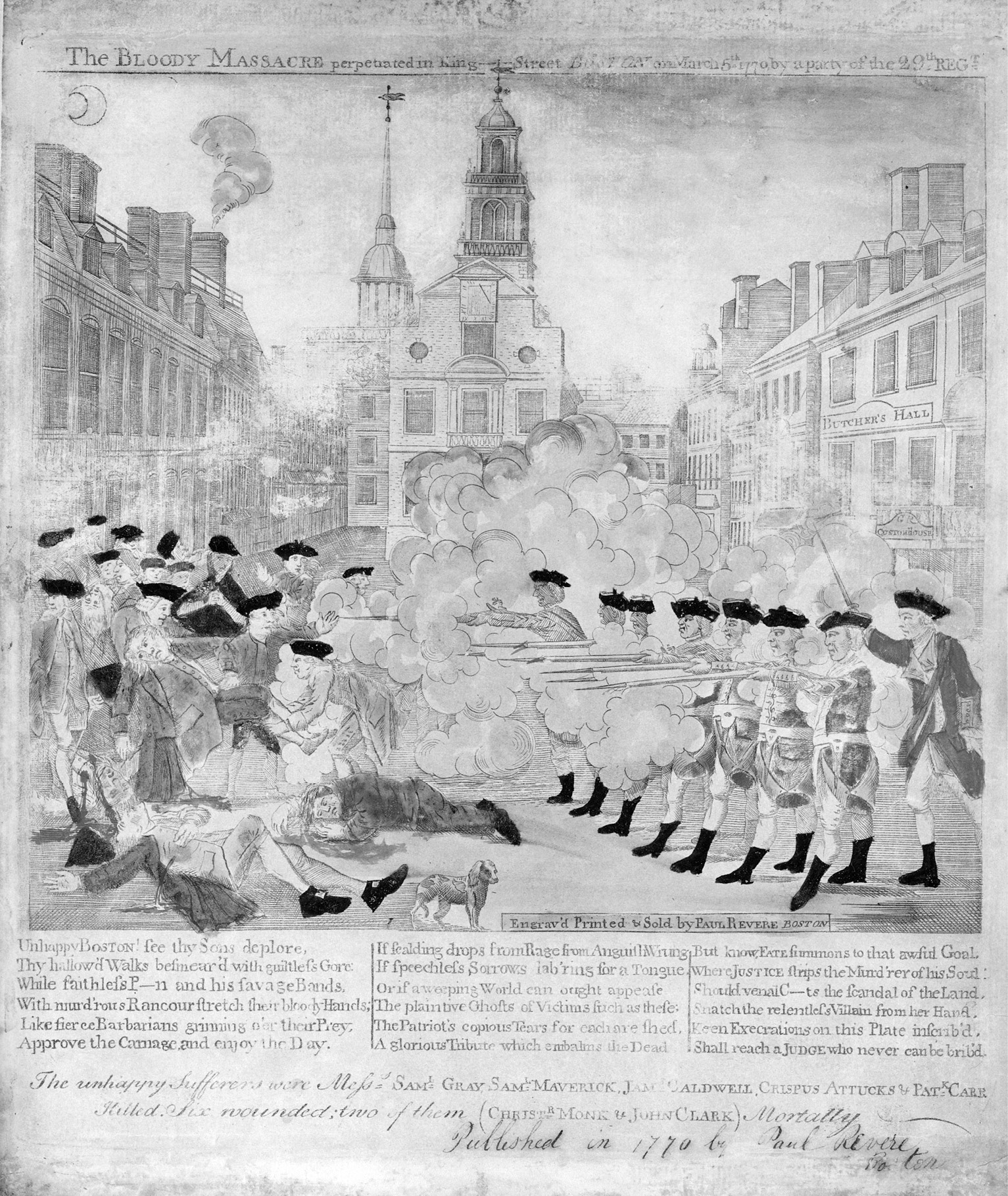

Paul Revere’s engraving defined the shootings of March 5, 1770, as the “Bloody Massacre” and was potent propaganda in turning the colonies against Britain. (Library of Congress)

Paul Revere’s drawings of coffins representing citizens killed in the Boston Massacre resounded throughout the colonies, driving home the consequences of a standing British army in their midst. (American Antiquarian Society)

John Dickinson energized the patriot cause by writing some of the most influential essays on the rights of the colonists. But in the end he could not bring himself to sign the Declaration of Independence. (Portrait by Charles Wilson Peale / Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park)

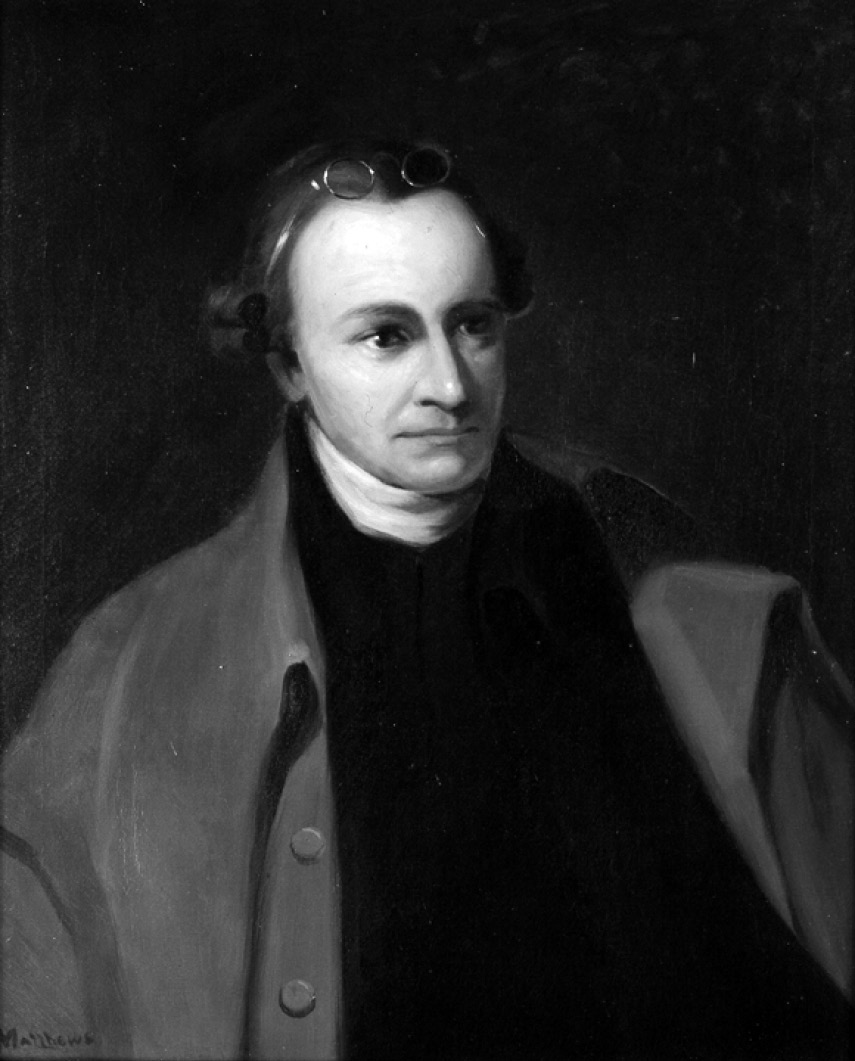

Patrick Henry brought forceful oratory to his opposition to the Constitution. The Virginia ratifying convention, though, narrowly approved the Constitution despite his strenuous arguments against it. Vigorous political speech during the ratification period signaled the founding generation’s embrace of robust expression. (George Bagby Matthews after portrait by Thomas Sully / Courtesy of the United States Senate)

John Adams wrote approvingly of vigorous dissent during the troubles with Britain, but as president he signed the odious Sedition Act to punish his political opponents. (Pendleton lithograph of portrait by Gilbert Stuart / Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

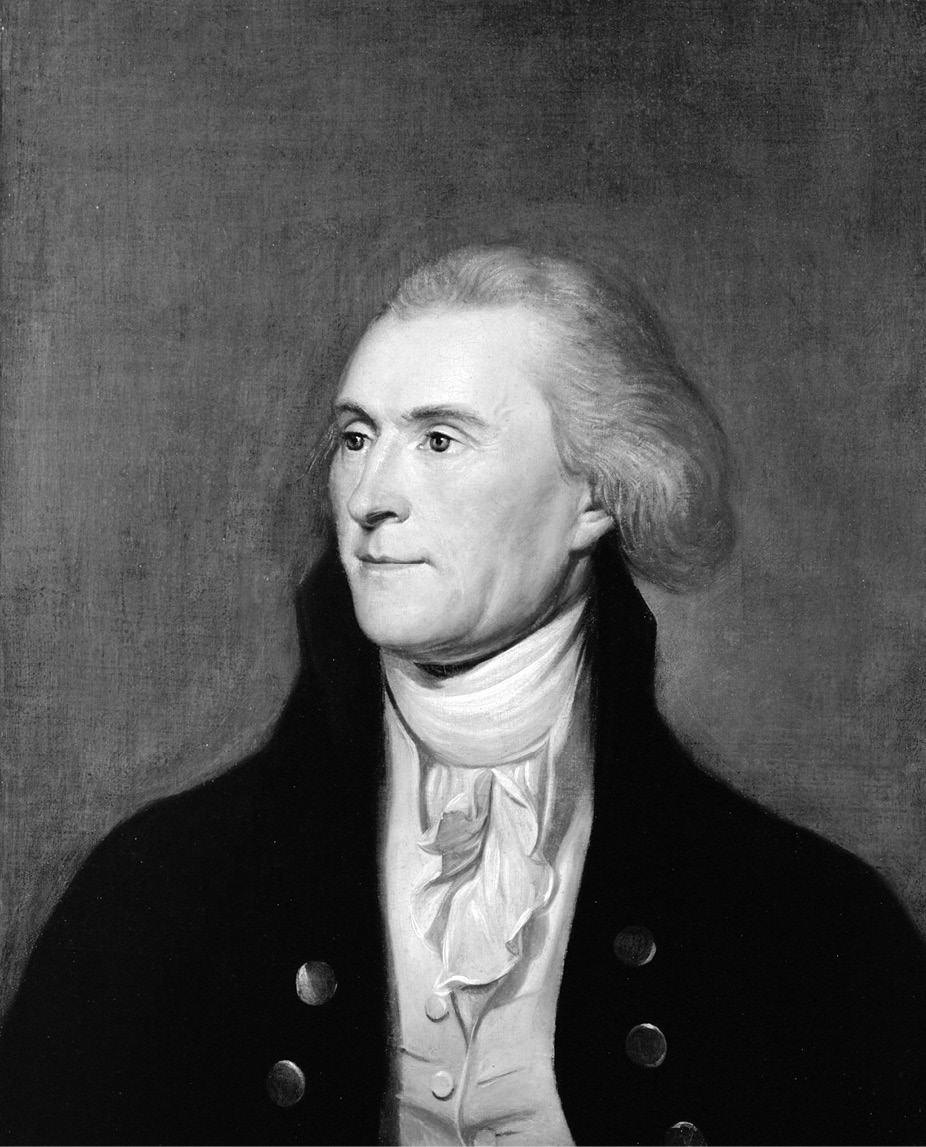

As vice president, Thomas Jefferson worked in secret alliance with James Madison to oppose the Sedition Act of 1798, the cudgel that the Adams administration used against dissidents. He had earlier helped convince Madison to support a constitutional amendment protecting the freedom of speech and press. (Portrait by Charles Wilson Peale / Courtesy of the U.S. Department of State)

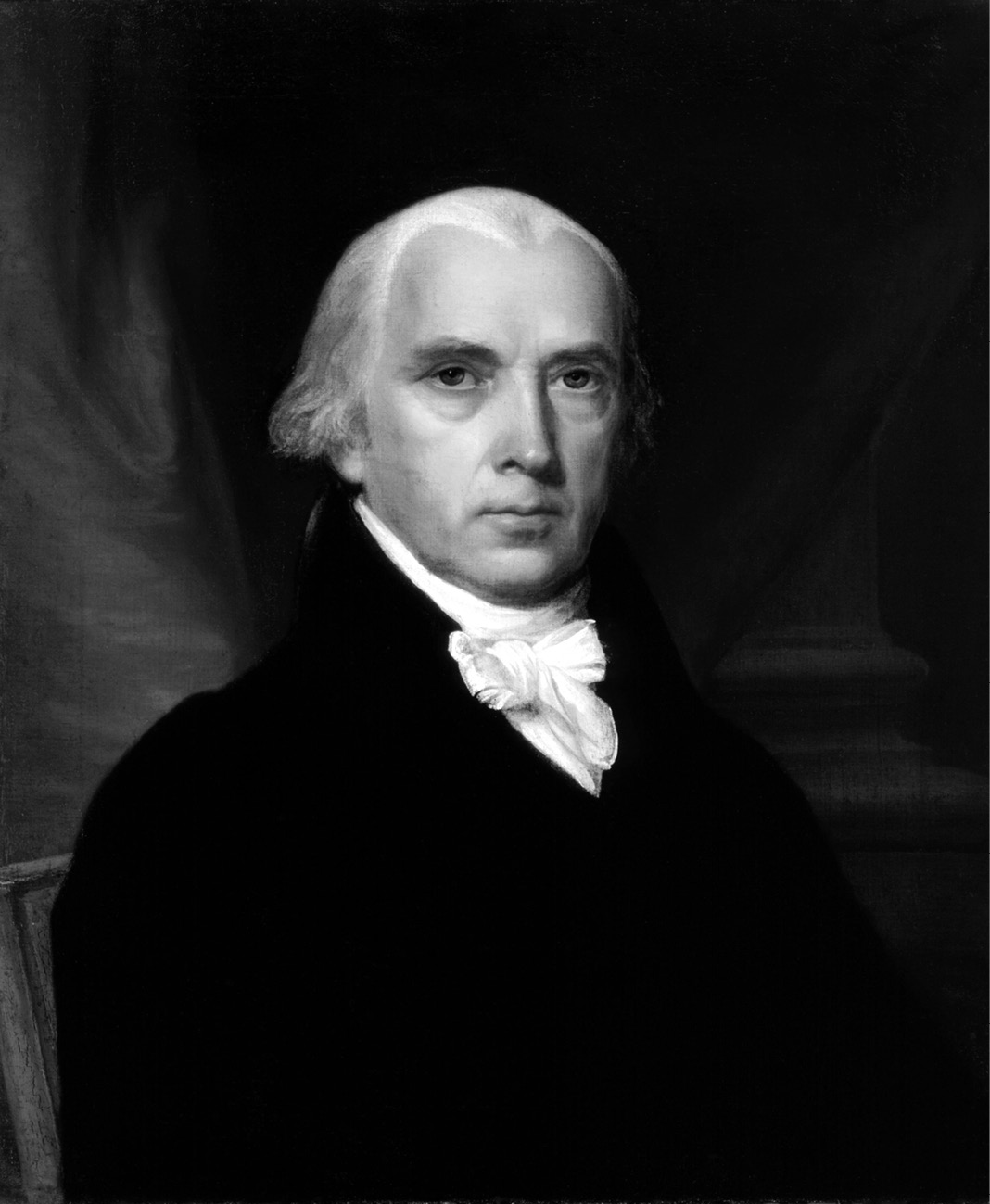

James Madison, the primary author of the First Amendment, wrote a resounding defense of the freedom of speech and press in 1800 in response to the Sedition Act. He tied freedom of speech and press to the needs of a self-governing society. (Portrait by John Vanderlyn / Courtesy of the White House Historical Association)