CHAPTER 2

… the great and perfect wisdom of God in His marvellous work of music …

Martin Luther

Running up the dark steps of the Church of the Commonwealth, Alan Starr didn’t notice the baby at first, crawling up the stairs ahead of him, all by itself.

He was absorbed in the muffled sound of the organ leaking through the closed doors. There were awful irregularities within each rank. No one would be able to judge the new instrument until he himself had voiced nearly three thousand pipes, nicking apertures, adjusting tongues, tuning wires and resonators.

Even so, even unvoiced, the organ responded brightly to James Castle’s catapulting counterpoint. The driving sixteenth notes fell on Alan’s ears like rain in a dry land. He had been born with a thirst for harmonious noise, for “Rock-a-bye, Baby” and all that came after. The sound of the new organ from Marblehead was piercingly clear. The old organ had never sounded like this, in spite of its fourteen thousand pipes and its swarming electropneumatic imitation of all the instruments in the orchestra.

But perhaps only James Castle was good enough to coax this sort of brilliance from the new organ. Castle was in a class by himself. He was, after all, the most famous student of the legendary Harold Oates. Since Alan in his turn was Castle’s pupil, he sometimes imagined himself a kind of musical grandson of the great Oates.

“Is it true?” he had once asked Castle. “Did he really play like that? You know the way people talk.” Alan rolled his eyes comically upward. “They say he was divinely inspired by God.”

Castle had guffawed. “Divinely inspired? Harold Oates?” But then he grinned at Alan. “Well, who knows? Perhaps in his own way he was.”

Now, hurrying up the church steps in the dark, Alan almost stumbled over the baby. He stopped short and looked at it in surprise. It was crawling up the cold stone steps of the Church of the Commonwealth, slapping down a hand on the step above, hauling itself up on one knee, sitting down with a thump, reaching up to the next step.

The baby was alone. No one else was climbing the steps behind it, or watching it from the sidewalk. What was a baby doing on the street alone in the dark? “Look here,” said Alan, “where’s your mother?”

The baby paid no attention. It caught sight of a man walking a dog along the sidewalk. At once it turned around and started down the stairs again, making extraordinary speed. Transfixed, Alan watched it patter after the dog, which was tugging its owner across Clarendon Street toward the building excavation on the other side. The traffic slowed down, then charged forward.

“Hey,” said Alan. He galloped after the baby and snatched it up just as it put a hand down into the gutter. The cars rushed by, oblivious, while Alan stood on the curb, looking down at the child in his arms, breathing hard.

In the light of the street lamp he could see that it was quite a nice-looking baby with alert blue eyes. Its cheeks were plump and dirty, with clean streaks where tears had run down. Its face had a kind of hilarious expression.

Whose baby was it? Alan looked along the row of town houses and up and down the tree-lined park dividing the two lanes of traffic on Commonwealth Avenue. A few kids were moving past the marble bust of a long-forgotten mayor of Boston, heading for the bars on Boylston Street, their shoulders hunched against the cold. The baby’s mother was nowhere in sight.

Music flooded out of the church. Castle was trying the reed stops. Even through the closed doors the sound was thrilling—the brilliant clarion, the rampant trumpet.

Alan had an appointment with Castle. They were to spend the evening in a swift overview of all the ranks, and Castle was going to say exactly what tonal values he wanted, and Alan was going to write it down. He was late. What the hell should he do with the baby?

It occurred to him that its careless mother might be in the church, listening to the organ. Holding the baby with one arm, Alan walked quickly up the steps. He had never held an infant before, but there didn’t seem to be much to it. The baby fitted comfortably against his shoulder and chuckled in his ear.

He pushed open the door with one elbow, walked across the vestry and entered the sanctuary.

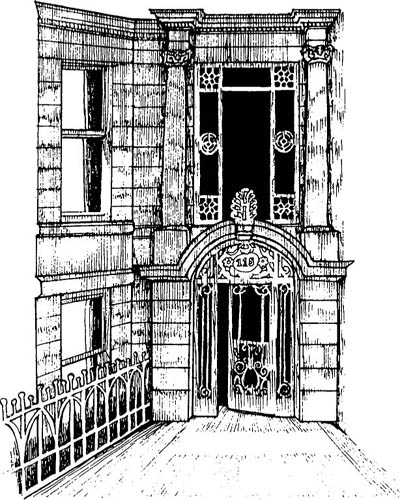

At once he was surrounded by the atmosphere of American Protestant holiness, circa 1887. The church had been built in obedience to the architectural ideals of John Ruskin. Ruskin’s lamps of Obedience! Truth! Power! Beauty! Life! Memory! Sacrifice! had shone upon the supporting pilings as they were driven into the damp silt and clay of the filled land of Boston’s Back Bay. The lamps had glistened on the rising walls of Roxbury pudding stone, on the checkered sandstone and granite of the tower, on the elaborate decoration of the interior. The winds of architectural fashion had long since blown out most of those noble lamps, one by one, but the usefulness of the building had not changed. It was still a sturdy and handsome structure, dark within, glowing with stained glass, gleaming with polished wood.

Only the lamp of Truth still flared up now and then, flickering brightly enough to fill the pews on Sunday mornings and brim the collection plates with dollar bills. The preaching, of course, had changed. The mild and respectable Protestant faith that had established the parish as a denomination unto itself in the middle of the nineteenth century had drifted farther from orthodoxy every year. The present pastor, Martin Kraeger, had started his ministerial life as a Lutheran, but he had grown farther and farther away from his background. Now what was he? A lapsed Lutheran, an occasional Transcendentalist, a moderate Unitarian, an unsilent Quaker and a wry Existentialist, with a few molecules of contemplative Buddhism thrown in. His congregation accepted the intellectual jumble. They seldom examined their pastor’s tissue of beliefs, or attempted to unravel one piece of patchwork from another.

Alan walked up the center aisle, holding the baby, inhaling the scent of extinguished candles, the leathery smell of the old Bible on the pulpit, the stuffing in the pew cushions, the lingering fragrance of perfumed sopranos and clean-shaven tenors. There was still a hint of scorching in the air, a sharp recollection of the fire that had burned the balcony and destroyed the old organ and taken the life of the sexton, old Mr. Plummer.

Alan winced as he caught the acrid scent, remembering the anguished look on the face of Martin Kraeger the morning after the fire. Alan had been called in at once, to assess the damage to the organ. He had examined it in the presence of Kraeger, James Castle and Edith Frederick, church treasurer Kenneth Possett, and the chief from the local fire station on Boylston Street.

Kraeger’s ugly face had been a study in wretchedness. He kept saying, “It was my fault.” He had been smoking carelessly, he said, up there in the balcony, talking to Castle. And there had been lighted candles all over the place for the evening wedding. Had old Mr. Plummer extinguished them all? Were some of them still burning under the balcony when Kraeger left at midnight with Castle? Only a few hours later it had gone up in flames.

Kraeger had already confessed his fault to the firefighters as they dragged their hoses around the burning building. He had confessed it to the people watching the fire as they stood gaping behind a rope barrier. He had told the reporter from the Globe and the kids with the video camera from Channel 4. All New England had seen him the next morning on the local news. There he was in person, weeping over the burned body of Mr. Plummer. It was a gruesome and pitiful picture. “Entirely unfit for children,” complained a committee of mothers in a letter of protest.

Alan had seen the episode on the morning news while he hauled on his clothes to go to the church. He had raced up Beacon Hill and down again from his room on Russell Street, and gasped his way across the Public Garden and arrived at the Church of the Commonwealth out of breath. Inside the sanctuary he found the others standing around the organ in the half-ruined balcony. As an organ student of James Castle’s, Alan already knew Reverend Kraeger and Mrs. Frederick. Church treasurer Kenneth Possett was new to him, and the chief of the local fire department, and another stranger who came puffing up the balcony stairs, stumbling over the charred remains of chairs recently occupied by the choir.

It was a tall man in a rumpled shirt. “My God,” said the man, “what a disaster. It’s hard to believe a careless cigarette could have done all this.”

“Oh, there you are, Homer.” Kenneth Possett introduced Homer Kelly to Martin Kraeger, Mrs. Frederick, James Castle, the fire chief, and Alan Starr. “Homer’s an old friend of mine. Right now he’s teaching at that ancient institution of higher learning across the river, but he used to be a policeman. I thought he might be able to help us figure out what happened.”

“It’s not just a question of cigarettes,” said the chief, turning to Homer. “It was candles too. That wedding, they had candles all over the place last night. It’s a wonder there’s any churchgoers left in the world, the way they go out of their way to burn themselves up with candles. Electricity, Jesus! You’d think Thomas Alva Edison never got born.”

“It was all my fault,” murmured Martin Kraeger. His exhausted face was still black with smoke. His hands were wrapped in bandages.

The fire chief looked at him grimly and said nothing, remembering the insane way Kraeger had rushed into the building at the height of the blaze to look for the missing sexton, endangering the lives of the firefighters who had to drag him out again—as if they didn’t have enough to do, saving the rest of the building, watering down the blowing embers, watching the roofs of the neighboring town houses. The man was a maniac.

Ken Possett turned to Castle. “The point is, what are we going to do about the organ? Can anything be salvaged? Is it a total loss?”

And then Castle turned to Alan, the visiting expert. Alan had already made up his mind. He had glanced at the scorched façade pipes and opened the narrow door to the chamber where the others were massed in their thousands upon thousands. Everyone else looked at him too, and he shrugged his shoulders. “It’s totaled, I’m afraid. Oh, you might salvage a few of the smallest metal flue pipes, but most of them are a dead loss. The wooden flues are wrecked, the solid-state control board is a mess, and the console”—Alan gestured helplessly at the blistered keyboards, the scorched rows of stop knobs—“well, you can see for yourselves, there’s nothing left.”

“All those pipes,” whimpered Ken Possett, “fourteen thousand pipes, you’re telling us they’re all gone?”

“Well, say, thirteen thousand nine hundred of them. I’m sorry.”

And then Mrs. Frederick stepped gallantly forward. “My mind is made up. The Church of the Commonwealth must have a magnificent pipe organ. Jim, I want you to pick the best in the world. It will be my gift to the church, in memory of Henry.”

Afterward Alan tried to picture Jim’s face—had there been a sly look of triumph? He couldn’t remember. He had been too interested himself in the idea of the new organ. He had wanted to nudge Castle and say, “Marblehead, right?”

But Castle did not need to be told. Next day Alan accompanied him to Marblehead and showed him the organ that had been ordered and cancelled by a failing church in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. And then it had taken the people in Marblehead only a few months to adjust it to Castle’s specifications.

And here it was, ready for tuning and voicing, Mrs. Frederick’s magnificent new tracker organ, with casework of cherry and three thousand five hundred seventy new pipes rising in tiers beside the stained-glass window of Moses and the Burning Bush. For the next few months its destiny was up to Alan Starr.

The baby was beginning to squirm. Alan jiggled it up and down, and walked along the center aisle until he could look back up at the balcony and see Castle at the organ console. There he was, high above the rows of pews, his back to the pulpit, the pipes rising around him.

The fugue came to an end. Castle lifted his hands from the keyboard and held up one finger. Alan was silent, listening. The baby listened too. “Four seconds,” said Alan.

Castle turned on the bench and looked down at him gleefully. “Four, right. Four seconds of reverberation. Pretty good. If we took out all the pew cushions we’d probably get five. Hey, what have you got there? Is that yours?”

“No.” Alan bounced the baby in his arms. “I found it outside on the steps.” He looked around. “I thought its mother might be in here someplace.”

“The baby was on the steps? You mean all by itself?” Castle got up and leaned over the railing to take a look. “Babies shouldn’t be left alone. Good Lord.”

“I think it’s going to sleep. Wait a minute. I’ll be right up.” Reaching into a pew he tumbled the cushion to the floor, then lowered the baby onto it and latched the pew door. “How’s that?”

“Looks okay to me, but what do I know about babies? Hey, did you bring the extra stop knob?”

“Sure.” Alan galloped up the steps to the balcony and took the blank stop knob out of his pocket. “What do you want it for?”

“Divine inspiration.” Castle took the stop knob and tried it in the empty space above Spitzflute and Octave on the panel for the Great organ. “Put it right here.”

“What do you mean, put it there? You want to add another rank? Good grief, you don’t start with a stop knob, for Christ’s sake.”

“No, no, I don’t want it connected to anything in particular. Just directly to God, that’s all. It’s for divine inspiration. I want you to paint DIV INSP on it. So I can give it a yank whenever I lose touch with whatever the hell’s going on in the service. You know, whenever Kraeger mumbles in his beard or my page turner drops the music.”

“Oh, right, good idea. Every organ should have a knob like that.”

They got to work. Castle went through the ranks for the Great division, and went on to the Choir, the Positive, the Swell, the Pedal. Alan took notes.

“When are the thirty-two-footers coming?” said Castle, using both feet to send a deep Bourdon fifth shuddering through the building.

“Soon, I hope. Hey, what’s that squeal?”

“God, it must be a cipher.” Castle turned around on the bench. “Oh, no, it’s not. It’s your little friend. The baby’s awake.”

Alan raced down the balcony stairs and picked up the baby just as it flung one leg over the arm of the pew. In another moment it would have fallen into the aisle. At once it stopped crying and smiled at him.

“Cute little critter,” said Castle, looking down from above. “Maybe it lives around here. Did you try the house next door?”

“No. Good idea.” Alan bounced the baby gently. “Look, the job should take me three or four months, if the thirty-two-foot pipes get here soon. But I’ll have the Great division done by the end of January. Mrs. Frederick wants to have a celebration. Can you find something to play on a single manual? Something really—what was the word—glorious?”

Castle turned away and shuffled his music. “Oh, that’s right, the end of January. Yes, yes, she told me. Oh, sure, there’ll be no problem finding the music. But I won’t be here. It will have to be somebody else. I’m going away for a while.”

“You won’t be here?”

“My mother’s ill. Very ill. I haven’t seen much of her in the last few years, and it’s high time I tried to be a dutiful son. Look, why don’t you take over the performance for the celebration? You’re the best student I ever had—next to Rosie, of course.”

“Rosie? Oh, of course, Rosie. I keep hearing about the magnificent Rosie.”

“You never met Rosie?” Castle laughed. “You sound envious. Well, you should be. She’s damned good.”

“Look, I’m sorry about your mother. Couldn’t you come back just for a day or two, to play the concert yourself?”

Castle picked up his music and stood up. “I think not.”

“Too bad. People aren’t going to be happy when I show up instead of you.” Alan shouldered the baby and began walking down the aisle.

“Oh, Alan,” said Castle softly, looking down over the balcony railing. “Goodbye. I probably won’t see you again. Before I go, I mean.”

“Oh, well, have a good trip. I hope your mother’s better soon. So long.”

Outdoors the December night was chill. Alan carried the baby past the church, and past the church office building next door. The next edifice in the block-long row of town houses was a five-story brownstone.

He stopped and stared at it in surprise. The front door was wide open.