CHAPTER 13

I should have no compassion on these witches; I would burn all of them.

Martin Luther

The door of Bowdoin Manor was open. The hall smelled of lavatory disinfectant. Alan wandered past a Pepsi machine and a row of doors, listening for children. All was silent. He climbed the worn rubber treads of the steep stairs. At once he was rewarded with the sound of a television and a crying child behind the first door. A slip of paper was taped to the door, with the name Deborah Buffington scribbled on it in pencil.

He knocked. The cries increased. In a moment the door opened a crack. It was still held by a chain. A thin child with a sharp face looked out at him. “What do you want?”

It wasn’t a child, it was the girl who had been pushing the stroller. Alan was ready with his story. “I’ve come to see Charles Hall. I’m a friend of the family.”

“Oh, sure, a friend of the family! An inspector, you mean, from Social Services. Well, I’m busy right now.”

“No, no. My name’s Alan Starr. I just want to see the baby.”

The pale eyes narrowed. “Are you the father?”

“No, no, the father’s dead. I told you, I just want to see the baby.” He had to speak up because the television was making a racket and Charley was bellowing.

The girl did not unchain the door. She stared at him sourly. “Why would you want to see the baby? What the hell for?”

Exasperated, Alan tried to explain. “I’m just interested in him, that’s all. I was the one who found him on the side-walk after his mother disappeared. I’m fond of him. I just want to be sure he’s all right.”

The girl was insulted. “Why shouldn’t he be all right?” She turned her narrow face aside and shouted, “Shut up. Just shut up.” She had been driven past some point of endurance. Relenting, she wrenched at a bolt, pushed back a bar, undid the chain and opened the door.

At once Alan went to Charley, lifted him out of his playpen and held him at arm’s length. Charley stopped crying with a final hiccuping sob, and smiled.

A scrawny little girl in pink tights stared at Alan, then turned back to the tumbling cartoon animals on the television screen. Excited music scrambled around the room.

“He knows you,” said the foster mother in surprise, folding her skinny arms across her chest.

“Of course he knows me. We’re old buddies.” Alan held Charley against his shoulder and looked anxiously at the girl. “How’s he doing?”

“Who, him? Oh, Jesus, like he eats everything in sight.”

“No, I mean, how are his spirits? Having his mother disappear like that, it must be hard on a little guy.”

“Oh, Christ, he never stops crying. God.”

“Well, you can’t blame him.” Alan kissed Charley’s damp cheek.

“And he’s stupid,” said the girl vindictively. “He doesn’t even talk or walk.”

“Well, isn’t he pretty young for talking and walking?”

“My daughter Wanda”—the girl jerked her head at the pale child in front of the TV—”she’s been walking since she was a year old, and talking too.”

Alan wanted to stick up for Charley’s intelligence, but he didn’t know anything about babies. “Well, he looks pretty smart to me,” he said lamely.

“Well, he’s not. He’s probably retarded. I’ll bet his mother left because she couldn’t take it any more. God!”

“Look,” said Alan, anxious to give Charley a vacation from this poisonous atmosphere, “may I take him for a walk?”

It was obvious that the girl was torn. How could she let a stranger go off with the child entrusted to her care? On the other hand, with Charley out of the house she’d have a few moments of peace. Alan watched her wrestle with her conscience. Lighting a cigarette, she hurled the match into the sink, took a deep drag and opted for peace.

On the street, with Charley snugly tucked into the stroller, Alan made for 115 Commonwealth Avenue. They were going home. It was a long walk, but it never occurred to him to take the baby anywhere else. He wanted to surround him with his old familiar life and show him his mother’s face on the wall.

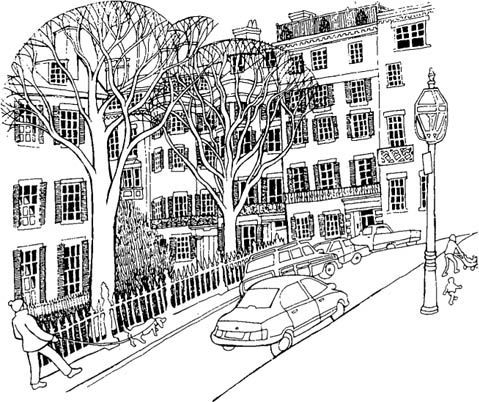

Up the hill they rushed toward the State House with its gold dome, and turned left on Myrtle Street. Alan bounced the stroller past a mattress leaning against a street lamp and a burlap bag that looked as if it might contain body parts, then turned onto Joy Street. Here seediness gave way to intense refinement and Bostonian charm, at—God!—how much per month?

The ascent was steep. Alan had to drag the stroller behind him all the way up to Mount Vernon Street at the crest of Beacon Hill, but from there it was downhill all the way. The stroller jounced on the cold bricks of Louisburg Square and raced past the shops on Charles Street. As they crossed the Public Garden, Alan ran the little stroller around the Ether Memorial on two wheels, and the baby squealed with joy.

In the alley behind 115 Commonwealth he had to face the problem of getting the baby over the wall. The problem was solved at once. There was a woman in Rosie’s garden, a thin old lady with dyed black hair. She was manipulating a trash barrel, dragging it through the open gate into the alley.

She recognized the baby at once. “Oh, it’s little Charley!” she cried with delight. Bending down, she cuddled his face with her hands. “Such a lamb. Where is your sweet mama, Charley dear?” She stood up and looked sadly at Alan. “Such a tragedy, that sweet girl! You’re taking care of him now? How nice that he has a foster father!”

Alan cobbled up a lie. It was remarkable how easily it came to him. “No, no, I’m not the foster father. I’m just a friend of Rosie’s. I thought I’d keep an eye on the baby, and bring him back home now and then. My name’s Starr, Alan Starr.”

The old woman put out her hand. “Doris Garboyle.” Mrs. Garboyle’s eyes were enmeshed in wrinkles, but they were clear and frank.

“Oh, yes, Mrs. Garboyle. You’re a housemother here, isn’t that right?”

“Upstairs, yes. The ground floor is all Rosalind’s. She grew up here when it was a real house. An elegant home.” Mrs. Garboyle sighed, and a tear ran down one cheek. “Have you heard anything from the police?”

“Not a thing.”

“Well, I hope they find her soon.” Mrs. Garboyle leaned down and kissed Charley. “This little chickabiddy needs his mother.”

“Is it all right if we go in? The police gave me a key to the back door.” Once again Alan was surprised at his easy disregard for the truth. “Oh, Mrs. Garboyle, I don’t suppose you have an extra key for the gate?”

“Of course, dear! I’ll get one at once. I’ve got four or five extras.” She hurried ahead of him, hugging her skinny arms to her sweater in the cold. The back entry was open. Mrs. Garboyle bustled through the second of the inner doors, and Alan caught a glimpse of the hall he had entered with the wandering baby on that eventful night before Christmas. “Back in a minute,” promised Mrs. Garboyle, closing the door behind her.

Alan unlocked Rosie’s back door and dragged the stroller into her apartment. At once he picked up Charley and carried him to the picture on the wall. Charley’s education began at once. “Look, Charley, there’s your mama. See Mama? That’s Mama, Mama, Mama!”

The truth was, Alan felt a parental sense of competition with little Wanda, who had walked and talked when she was only twelve months old. By God, he’d teach Rosie’s infant son to talk.