CHAPTER 17

The word of God … meets the children of Ephraim like a bear in the way and a lioness in the woods.

Martin Luther

It was Alan Starr’s turn to play the midday Friday concert at Trinity Church in Copley Square.

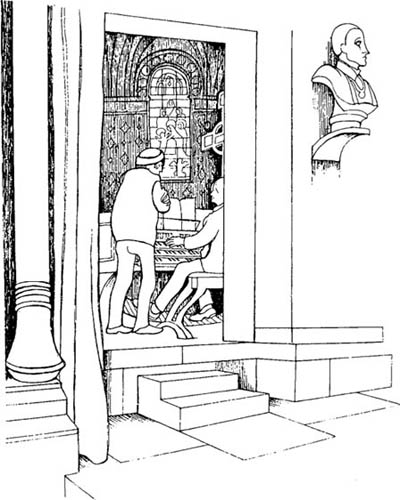

The electropneumatic organ was not to his taste, although it was an enormous one with seven thousand pipes. The console had a place of honor at one side of the broad chancel, below Henry Hobson Richardson’s golden walls and arching golden heavens. Beyond the chancel rose the massive piers supporting the giant tower. The decoration of the church was a combination of Byzantine mosaic and painted stencilling and sumptuous frescoes and brilliant stained glass, with a superimposed touch of Art Deco. Alan could never make up his mind whether it was a magnificent masterpiece or just plain awful. Its reputation was too august to question, its effect on the beholder too intimidating. BLESSING AND HONOUR AND GLORY AND POWER, thundered a legend high on the wall.

Now, sitting on the organ bench, Alan felt giddy, poised all alone in shimmering air. Beyond the railing he could see the entire audience, a slim scattering in a forest of oaken pews. In the last decade of the twentieth century few people attended organ concerts but other organists. All Alan’s friends were there—Pip Tower, Barbara Inch, Peggy Throstle, Martha Moore and Jack Newcomb—and some of the older professionals—Arthur Washington, Melanie Chick, Gilda Honeycutt.

And as always in the wintertime, a few street people had come in out of the cold. Alan was amused to see the three dingy derelicts he had met the other day in the company of little Charley—Tom, Dick and Harry. Tom was asleep, Dick was crouched over a comic book, Harry sat with bowed head.

Alan played Buxtehude and Franck. The thick, muffled quality of the organ was fine for the Franck, less fine for the Buxtehude, but the audience applauded politely as he finished the concert and came forward to the chancel rail to bow.

Then his friends walked up the chancel steps and clustered around the organ to praise his performance. “How’s the job search coming?” said Alan, making polite conversation with Pip Tower. “Are you still working at that hospital?”

Pip looked grave. “Oh, sure. I’m a lowly hospital orderly. I deliver X rays, I wash mattresses upon which people have gone to a better world, I bathe dead bodies. Super. And I just started working in a copy center at night.” He brightened. “I heard about the interim job at Commonwealth. I understand there’ll be auditions.”

“That’s right,” said Barbara Inch. “I’m going to try out too, but you’re a shoo-in. The rest of us haven’t got a chance.”

Pip looked at Alan anxiously. “What do you know about the committee?”

“Well, I suppose Mrs. Frederick’s in charge.”

“Oh, Jesus, she doesn’t know a fucking thing about music. What about you? Are you going to audition?”

“Me?” Alan laughed. “And compete with you? Heck, no. I’d have to be out of my mind.”

Barbara and Pip drifted away. Everyone else had vanished too. The vast acreage of pews was empty. Alan gathered up his music, but as he slid off the bench and stood up, he was surprised to find the man who called himself Harry slouching against the wall behind him.

He looked worse than ever. He had pulled off his knitted cap, and his thin hair stood straight up on end. His eyes were bleary and cunning. “You can do better than that,” he said. “The registration on the Buxtehude, it was pure shit.”

He lunged forward and switched on the organ. Alan looked on, flabbergasted, as Harry sat down and fumbled with the stops. He played a chord, and a threadlike Dulciana spiraled out of the organ and floated in a delicate veil over the dark spaces of the church.

Stunned, Alan listened as the gray man with the ruined face ran through the Buxtehude, then launched into a Bach fugue. His feet raced over the pedals in a monumental walking bass, and then with a surging combination of reed stops, his hands gave chase.

His touch was faultless. Without the evidence of his eyes Alan would have thought he was listening to James Castle’s perfection of pace and sparkling clarity. But here there was something more, something unleashed, something transfigured, something free and wild.

The last measures crashed out of the pipes and ricocheted from the golden walls and the mosaics of prophets and the glassy surfaces of the windows and the lofty curvatures of the barrel vaults, and died away at last after seven long seconds.

Awestruck, Alan leaned toward Harry and whispered, “What did you say your name was?”

Harry turned off the organ. The pneumatic wind died down. His small red eyes glanced at Alan, then darted away. “Oates,” muttered Harry. “Harold Oates. You might have heard of me.”

Alan gasped. “Oates, Harold Oates? But I thought you were—?”

“Dead?” Oates laughed. “Well, you’re right. I died a long time ago. What you see before you is a stinking corpse.” Sliding off the bench, he stood up.

Tom and Dick appeared from nowhere. “Don’t he play good?” said Dick.

“Gawd!” said Tom.

“AA, that’s what done it,” said Dick. “You should’ve seen him, last year when he first come. Welfare sent him. Tanked.” Dick waved his hand. “Tanked up to here. Really stewed. Tom, he brought him in.” Dick clapped Tom on the back. “Of course Tom’s mostly half-pissed himself.”

“Right,” said Tom. “Gawd!”

“But where have you been?” said Alan. “It must be twenty years since—you know, since you were giving regular concerts.”

“Dead,” said Oates again. “I told you.” He turned away and moved down the chancel steps with Dick and Tom.

Alan leaned over the railing. “How can I get in touch with you? Where do you live?”

“Among the lilies,” snarled Oates.