CHAPTER 19

The Holy Spirit is a fierce thunder-clap against the proud.

Martin Luther

Alan felt like a fool for letting the great Harold Oates slip through his fingers. Why had he let him go? He should have run after him when he walked out of Trinity Church. Alan suspected it had been some kind of unconscious snobbery on his part, Oates had looked so sleazy and weird.

He had to be found. Alan tried the phone book, but of course it contained no entry for Harold Oates. He sat on his bed and stared at the telephone. There were now two voids in his life. Rosie Hall and Harold Oates.

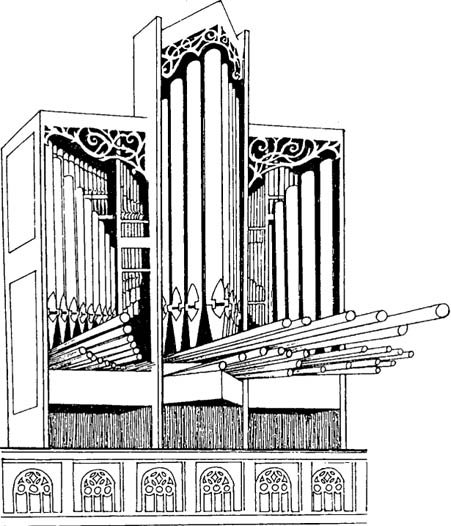

But next day Oates turned up in the Church of the Commonwealth while Alan was experimenting with one of the newly voiced ranks of pipes in the Great division, the four-foot Clarion. He had set up a voicing machine in the balcony, a shelf of slots with a keyboard, so that he could sometimes work without a partner.

He set the smallest pipe in one of the holes and listened to it. Was it out of tune? The whole rank was apt to go sour in wet weather.

Fortunately the winter had continued to be cold and dry. People were complaining about the lack of snow. Ski resorts were desperate, farmers were afraid of an entire winter without moisture, nurserymen dreaded the drying out of their stock.

Alan romped through the merry allegro from an organ concerto by Handel. The Clarion sounded fine, a little strident and nasal the way it should. When he rollicked through the last measures, he heard a dry clapping from the floor below. He turned to see Harold Oates looking up at him.

“What else can it do?” said Oates.

Alan wanted to cheer, but he was afraid to spook the elusive master. “Come on up and take a look.”

Oates came. He looked worse than ever in a too-large overcoat and a too-short pair of trousers. But his clothes were not the problem. Oates could be fitted out by Louis or Brooks Brothers, and he would still look gross. His face was a study in decrepitude. Twenty years of heavy drinking had dulled his small eyes and sunk them into their sockets. The skin of his face drooped in swags and pouches. Even his balding forehead looked odd, flushed with patches of color as red as his nose.

Alan wanted to kneel at his feet. He merely slid over casually on the bench as an invitation.

For two hours they experimented with the new organ. Oates muttered and said little, but his eyes glittered, and his combinations of stops were clever, startling, a revelation.

“Fucking thing’s got no bottom,” complained Oates.

“Most of the sixteen-footers are still in the shop. Wait till you hear the thirty-two-foot Contra Bombarde.”

“What’s this here?” growled Oates, putting a dirty finger on the knob labelled DIV INSP.

“Oh, that. It was Castle’s idea. Divine Inspiration. It’s just a joke.”

Oates uttered a sharp bark of laughter, which brought on a fit of coughing. He coughed and coughed. His coughs were terrible hacking explosions. In dismay Alan leaped up to find a glass of water. The man seemed to be expiring before his eyes.

But Edith Frederick stood at the top of the stairs, looking shocked. “Is he all right?” she whispered.

Oates stopped coughing. His face was purple, his eyes streaming. He glowered at Mrs. Frederick and wiped his nose on his sleeve.

“Oh, Mrs. Frederick,” said Alan nervously, “I’d like you to meet my friend Harold Oates, the—ah—distinguished organist.”

“How do you do, Mr. Oates,” said Edith. Her tone was frosty. It was clear that she had never heard of him.

Oates leered at her, then pulled out a couple of stops and played a deep blatting chord like a Bronx cheer.

Alan closed his eyes and Edith scuttled down the balcony stairs.