CHAPTER 31

By these monstrosities I am driven beyond modesty and decorum.

Martin Luther

Like Alan Starr, Mary Kelly was rummaging through her closet. In her case it was a matter of finding a new persona. She had sent away to the Morgan Memorial her jacket with the silver buttons, the one that was so much like Mrs. Frederick’s, along with her pleated skirt and her shoes with the pompoms. Everything else in the closet now seemed suspect. Her entire wardrobe was excessively respectable.

Abandoning the closet she looked through her dresser drawers and pulled out a snaky black garment and a pair of black tights. On the floor of Homer’s closet she found a pair of black sneakers that had once belonged to her nephew John. As a last touch she twisted a red bandanna around her forehead.

In the meantime Homer was on the phone, trying to find the cranny of the Boston Police Department in which Rosalind Hall’s burned pocketbook was lurking, along with its identifying credit cards and driver’s license. After eight calls, he succeeded.

“The faceless bureaucracy has yielded up its secrets,” he told his wife as she came out of the bedroom. Then his jaw dropped. “My God, woman, what’s that?”

Mary hunched down and hurried past him, heading for the kitchen. “Oh, it’s just my new outfit.”

“My dear, you look like a pirate.”

“Good. Just so I don’t look like that woman at church the other day. You know, Mrs. Frederick.”

“My dear, if there’s anyone on earth you do not resemble, it’s Mrs. Frederick.”

“Will you be ashamed to be seen with me?”

“Good Lord, no. My insane wife, I’ll say, and everyone will nod their heads and smile and be kind to me, saddled as I am with an unsuitable mate.”

“Oh, Homer, you do see, don’t you? You see what I mean?”

“Of course I do, my darling.” Homer embraced her. “And I don’t care what you wear. You always outqueen everybody else, just by being yourself. Damn them all.” He backed off and looked at her again. “It’s true, you look really swashbuckling. All you need is a cutlass. Do you want to come with me?”

“Oh, no, thank you, Homer.” Mary made nervous dashes around the room, collecting coat, bag, car keys. “I’m going to lunch with Ham Dow. He’s invited some of the women faculty to lunch.”

“You’re having lunch with the president of Harvard?”

Mary looked down at herself again. “Oh, don’t worry. Professor Dalhousie will be wearing her shroud, like Emerson’s aunt, and Jane Plankton will be there in a velvet gown, the one that trails along the floor, and Julia Chamberlain will be wearing something smashing. I couldn’t wear my prim little Johnny Appleseed outfit in that company. Thank God, I’ve burst out of my chrysalis at last.”

“Well, congratulations, Mary dear. The butterfly flaps her wings.”

The Evidence Locker for the Boston Police Department was housed in a building on Berkeley Street. Homer found the right door and walked in and put his hands on the counter and smiled ingratiatingly at the police officer in charge, a shapeless woman with dull eyes and a gray face.

Her voice was flat. “You got a form?”

“Yes, I do.” Homer produced his request for AUTO FIRE 986702, Exhibit H, Rosalind Hall, deceased victim; handbag. The form was signed by Francis Xavier Powers, District Attorney of Suffolk County.

“Just a minute.” The woman strolled out of the room with the form. From the next office he could hear her in lively conversation. She had been on a winter cruise. There had been dancing and shuffeboard, a shipboard romance. Homer heard envious squeals. At last the gray woman came back and dumped a large plastic bag on the counter. A tag was attached, CHAIN OF POSSESSION OF EVIDENCE, with the signatures of the several officials through whose hands it had passed.

“Don’t touch,” she warned him, withdrawing a flattened black object. “I got to do all the handling. Like, nobody else is allowed.”

The pocketbook belonging to Rosie Hall had once been brown, but now it was black. Most of the leather surface had been scorched. The gray woman reached in and drew out the contents, one article at a time. They were blackened but recognizable.

“May I see what’s in the wallet?”

The woman shrugged and raised her eyebrows. She pulled open the billfold carefully, displaying scorched twenty-dollar bills, a couple of fused plastic credit cards and a warped driver’s license. The sober face of Rosalind Hall was dimly visible on the license.

“What’s in the zippered bag?”

“It’s just cosmetics. I already looked.”

“Please may I see?”

The woman was displeased. She tugged back the zipper with a petulant motion and shook out the contents with a violent gesture.

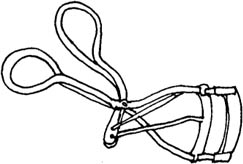

A fragrance of cheap perfume rose from the heap of cosmetics, mingled with the acrid smell of scorching. Homer was baffled. He could recognize the lipsticks, the melted comb and the cracked mirror, but what were all the other things? There were flat round containers, small square boxes, cylinders and pencils, and a device like an instrument of torture.

“What’s that?”

“That? It’s an eyelash curler.”

“An eyelash curler?” Homer was stunned. “How does it work?”

The woman came to life. “Wait a sec. There’s one in my bag.” She turned away swiftly, took a shiny pocketbook from the drawer of her desk, reached in, pulled out a nearly identical cosmetic case, and emptied it on the counter next to Exhibit H. Picking up her eyelash curler in one hand and a pocket mirror in the other, she crimped the pale lashes on her upper lids until they stood straight up, kinked at right angles.

“Good Lord.” Homer waved a hand at all the rest. “Could you demonstrate these too?”

“Well, okay.” She got to work with a will. The subject of cosmetics was the woman herself. It was something she was interested in. She jabbered, explaining. “First you got your foundation cream—then your powder—your blusher—your eyebrow pencil—your eyeliner—your eye shadow—your mascara. You got two kinds of lipstick, see? Like, you put this one on first, and then you frost it with the other one.”

Homer watched like a neophyte in a temple to an unknown god. In five minutes the gray woman had transformed herself into a white and pink doll with phosphorescent lips like the mouth of a corpse and eyes like bugs with a thousand legs. She was a work of art.

Humbly Homer thanked her and went away. Heading for Storrow Drive he pulled over impulsively and parked on Clarendon Street beside the Church of the Commonwealth.

He found Alan Starr in the vestibule with his nose pressed against the glass doors of the sanctuary. “Baptism,” he explained. “Always some goddamned interruption.”

Homer looked too. “Ugly little kid,” he said. “Not like our Charley.”

Alan grinned at him. “Just what I was thinking myself.”

“Look here,” said Homer, “I’ve just come from the Temple of Cosmetic Craftsmanship, and I want to tell you all about it.”

“The temple of what?”

“Evidence Locker, Boston Police Department. Rosalind Hall’s burned pocketbook, I’ve just seen it.” Homer told Alan about the credit cards, the driver’s license, the money, the cosmetic case with its contents—the eyelash curler, the mascara, the eyebrow pencil.

“But that’s ridiculous,” said Alan. “Rosie would never have used all that stuff.”

“Ah,” said Homer, looking at him wisely, “I thought you might say that. But you never met the woman. How do you know what she would do?”

“Well, just look at her photograph,” said Alan angrily. “She’s not wearing a lot of trashy stuff. I can’t believe she wore makeup. Give her credit for some consistency.”

Yesterday Homer would have agreed with him. But this morning his wife had driven off to Cambridge completely transformed, a new woman. He shook his head doubtfully. “Well, I don’t know. I just don’t know.”

“Oh, Homer, for Christ’s sake, it’s just like the car radio. That didn’t fit Rosie either. She would never have tuned to that station, and she would never have worn all that stuff on her face. And Charley saw her, don’t forget that. She’s still alive, I tell you. Somebody wants us to believe she’s dead.”

The baptism was over. Martin Kraeger came out into the hall, nodded at Homer, and held the door open for the mother, the father, the baby, the sister, the brother, the grandparents and godparents. Everybody was smiling. Even the ugly infant was smiling, surrounded by a whole population of parents and well-wishers—unlike poor handsome little Charley, bereft of loving relations.

Homer walked back to his car. Idly he glanced at the excavation across the street from the church. Nothing seemed to be happening down in the hole. The machinery sat motionless.

The truth was that the hotel project was in serious trouble. Things had gone from bad to worse. The majority stockholder in the realty trust had suffered an apoplectic stroke. All hell had broken loose. The other members of the board were bickering among themselves, unable to make a decision while his life hung in the balance. In the meantime the arrangement with the contractor had been slyly cancelled and a new document signed, awarding the job to the brother of an alderman. There were suits and countersuits, restraining orders, fistfights, court appearances for assault lodged by both sides.

The job engineer didn’t give a damn. He was busy with another dirty job, way down Route 95, building a slurry wall, only there’d been hell to pay from the beginning. The clamshell bucket busted its teeth on a boulder, and then the concrete refused to sink to the bottom of the slurry and had to be pumped out again, and the pump got choked and jammed, and the whole thing was a bag of shit.

The buried sump pump under the excavation of Clarendon Street and the switch that had been left on instead of off were the farthest things from his mind.