CHAPTER 40

Though earth all full of devils were,

Wide roaring to devour us;

Yet have we no such grievous fear,

They shall not overpower us.

Hymn by Martin Luther

Homer Kelly ran into Alan Starr in the Boston Public Library. Alan was hunched over a table in the reading room. Books lay beside him, but he wasn’t taking notes. He was writing to Rosie Hall in her notebook, writing about music.

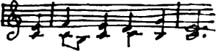

Have you ever read what Schweitzer says about the way Bach uses certain patterns to express specific emotions? One of the motifs I like best is the use of dissonance at the end of a piece, resolved in harmony, as in O Sacred Head:

Those dissonant notes send shivers up my spine, and then it’s so great when they smooth out in a major chord. It’s sort of like banging your head against a stone wall because it feels so good to stop.

Alan leaped in his chair when Homer Kelly touched his arm. Guiltily he slapped Rosie’s notebook shut and stood up, knocking over the chair. In the vast spaces of the reading room with its lofty barrel-vaulted ceiling, the crash echoed and re-echoed, and heads looked up from the other end of the room a quarter of a mile away.

Homer righted the chair and took Alan’s arm and led him away into the Delivery Room, where books could be requested and where they sometimes, hours later, arrived. Pale scholars leaned on the counter, worn down by years of waiting.

“Listen,” said Homer, “I’ve been thinking about pairs of things.”

The Delivery Room was resplendent with blood-red marble. Alan stared at the mural over the fireplace, a languid procession of Pre-Raphaelite noblewomen. Vaguely he remembered that they had something to do with the quest for the Holy Grail. “Pairs of things?”

“Two fires, the one at the church and the car fire, and two disappearances, Rosie’s and Castle’s.”

“Castle’s! But he didn’t disappear. His mother—”

“Is ill, or so he gave everyone to believe.” Homer looked at Alan gravely over his half-glasses, while ghostly scholars shuffled by, pursuing Holy Grails that were missing from the shelf or stolen by unscrupulous students or loaned to greedy professors with extended borrowing privileges.

“But it was overdue a month ago,” whimpered an untidy man, who looked as if he had been sleeping in the library and hadn’t eaten for a week. Homer gripped Alan’s arm again and urged him out into the golden ambience of the great stair hall.

“What do you mean,” said Alan, “gave everyone to believe? Why would Castle lie about his mother being ill?”

“Well, it’s interesting that his departure nearly coincided with Rosie’s. And we don’t know where he is, any more than we know where she is.”

Alan looked at the stone lions resting halfway down the stairs. They were gazing sleepily into nothingness, remote and disinterested in all human concerns, like those gods that created the world and abandoned it to its fate. “Well, you know, I’ve thought about that. I wish I knew more about Jim Castle. Martin Kraeger told me something sort of weird about him. He dropped in on him last Thanksgiving, and it was really embarrassing because he walked in on a screaming session. Castle’s mother—you know, the mother who’s supposed to be so sick—was there and she was really yelling, and there was this sick sister on the couch, and a bunch of other embarrassed relatives standing around. Martin left right away, and he never did find out what it was all about.”

“Strange, the ways of families,” said Homer. “You’d think a fine musician like Castle would come from a really supportive household.”

“Like Bach’s family,” agreed Alan. “You know, the whole family all singing and playing instruments together.”

“But it doesn’t always work that way. Sometimes the family is a barrel of snakes, and the poor little genius has to escape and make his own way.” Homer looked at Alan and added softly, “Could Castle have been in love with Rosie? You know, a teacher in love with his student? It’s happened plenty of times before.”

“God, I don’t know. I guess I thought he was more interested in men than in women. Most male organists are gay. It’s just a fact. I don’t know why the hell it’s true, but it is.”

“Do you have any reason for thinking he wasn’t heterosexual?”

“Oh, I guess I thought he liked me. He was very kind to me, and once—well, once he put his arm around me kind of, you know, lovingly, after I played something for him. I was too surprised to respond. Anyway, I didn’t, and that was all there was to it.”

Homer sat down on the marble balustrade and folded his arms. “Well, suppose he was heterosexual after all, and in love with Rosie? Do you think he might have carried her off by force, leaving her child behind and a pool of blood on the floor?”

Alan smiled and shook his head, telling himself once again that the idea was ridiculous. “I certainly don’t think so.” Then he remembered something he had forgotten. “Two fires, you said. Listen, he was in a fire before.”

“Castle was in a fire?”

“He told me about it. His hand was bandaged afterward. He couldn’t play for a week or two. His whole house burned down. It’s one of those town houses near Louisburg Square, and the fire shot up the staircase in the middle of the night, so he was lucky to get out alive.”

“When was that?”

“Oh, a couple of years ago.”

“He owned the house?”

“Right. He collected a lot of insurance, but not until he hired some expensive lawyer to sue the Paul Revere Insurance Company.”

“Three fires then, but possibly unrelated. Of course I’ve heard a rumor that Castle had a motive for setting fire to the balcony of the Church of the Commonwealth.”

“You mean, to burn up the old organ on purpose? That’s absurd. He’d never do a thing like that.”

“Tell me, was Castle a smoker? Was he smoking along with Kraeger on the night of the fire?”

“He might have been, I don’t know. He used to smoke, I remember that. But I’m pretty sure he gave it up.”

Homer clapped Alan on the arm and said goodbye, then walked down the marble stairs and out into Copley Square. Before heading for the subway he paused to admire the bronze figures of Art and Science, graceful maidens in classical draperies seated on either side of the library steps.

It occurred to him as he boarded the Green Line that the city was full of allegorical women. It had been a fixation with painters and sculptors at the turn of the century. Jammed into the crowded subway car, grasping a pole, hurtling through the dark in the direction of Park Street, Homer wondered about Alan’s idealized allegorical woman, Rosie Hall. It was true, her picture looked noble enough, but maybe she wasn’t the goddess Alan thought her. Maybe she was nothing but a selfish young woman who had left her poor child in the lurch.

And maybe she wasn’t anything at all, because perhaps—indeed probably—Rosalind Hall was dead.

Homer shuffled out of the car at Park Street in a thick mass of students and commuters. He was reminded of the snakes he had been talking about with Alan, the seething mass from which a talented person could sometimes escape. Where in the whole sprawling universe was James Castle? And where was the family of snakes, slimily crawling over each other?

“Oh-ho, Miss High and Mighty, now you’re not going to speak to me either! I see, it’s a conspiracy. You and Sonny, taking sides against me!”

“Oh, God, Mother, will you let her alone?”

“All I’m doing is following doctor’s orders. Can’t you see she needs a sedative?”

“Oh, no, oh, please, please, no!”

“Helen, you’ll do as I say! You need a sedative and I need a rest. Come on, open your mouth!”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake, can’t you see she doesn’t want it?”

“Helen, hold still!”