CHAPTER 42

If you think rightly of the gospel, do not imagine its cause can be accomplished without tumult, scandal, and sedition.

Martin Luther

Harold Oates brought home to his room from the Church of the Commonwealth one of the four-foot Gemshorn pipes, because that dumb kid Alan Starr hadn’t got it right, and now you couldn’t do a damn thing about it without a blowtorch.

He put the pipe down on his bed and looked at the propane torch he had picked up in a hardware store. How did the fucking thing turn on? Oates fiddled with the knob. At once a blast of blue fire squirted out of the nozzle and ignited the window curtain.

Martin Kraeger was sacrificing his Tuesday afternoon to promoting the welfare of Harold Oates. He usually devoted the afternoon to putting together rough notes for a sermon. During the rest of the week a rash would break out in his mind and some of the notes would develop growths and warts, which would effloresce and expand over half a dozen sheets of paper.

But it was the only time available for obeying Edith Frederick’s demand that he talk all his fellow clergymen into arranging concerts for Harold Oates.

“And be sure to inquire about practice time,” Edith had said. “Alan told me their pipe organs must be made available ahead of time. And keys! He’ll need keys to every single church.”

So Martin put aside his infant sermon and called the music directors at Emmanuel and Trinity, the rectors at Advent and St. John the Evangelist, the ministers at Old South, Arlington Street, King’s Chapel, First Baptist and the Church of the Covenant, the presiding priest at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, and the First Reader at the Mother Church of Christian Science.

He was almost totally successful. Nearly all of them were willing to fit a concert by Harold Oates into their schedules of spring activities. Even the cleaning woman at the Church of the Annunciation was enthusiastic. “I’ll tell Mr. Baxter,” she said. “I was there the other day, at that concert in your church. That Harold Oates, he’s just fabulous.”

But the consequences of Kraeger’s success in arranging concerts were not entirely happy. Within a few weeks there were querulous complaints.

“He was practicing when the wedding party arrived,” reported the music director at Trinity. “He refused to leave. We had to pick him up bodily and deposit him on the sidewalk.”

“He’s sleeping in the pews,” said Ronald Baxter, the rector at Annunciation. “We can’t have that.”

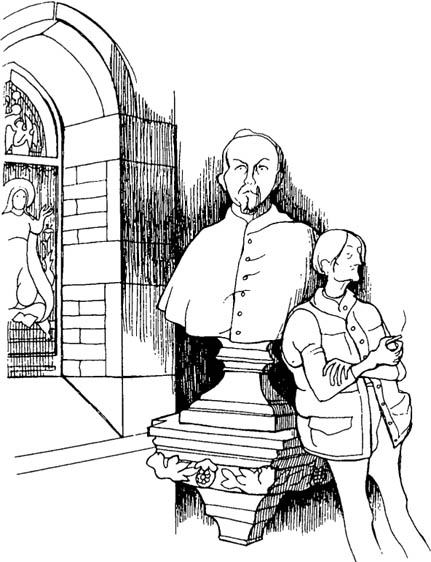

“I caught him smoking in the Lady Chapel,” said the assistant rector at Advent, “leaning against the bust of Bishop Grafton. His shirtsleeve was on fire.”

“He invaded the chancel during Communion,” reported the rector at Emmanuel. “We thought he was taking the wafer, like everybody else, but instead he snatched the cup from the celebrant and drank it down. I was horrified, I can tell you. The man must be mad.”

“He drank the wine?” said Martin Kraeger. “That’s bad news. He’s supposed to be on the wagon.”

Kraeger decided to speak to Oates when he next appeared at Commonwealth to rehearse the St. John Passion with Barbara Inch’s choir. On the next Saturday morning he sat in a pew, waiting, while Oates played a continuo accompaniment and the choir took all the blame for the crucifixion upon themselves:

My own misdeeds were far more

Than grains upon the seashore,

Than multitudes of sand.

’Twas my misdeeds that maimed Thee

With agonies that shamed me,

As though they came by mine own hand.

“Don’t screech, sopranos,” said Barbara. “One doesn’t screech a confession. Listen to the altos. Humility, that’s what the altos have got. Good for you, altos.”

It was a strange doctrine of faith, thought Martin Kraeger, that God’s son should suffer a gruesome death in order to give human sinners a chance at paradise. He himself did not believe the doctrine, but Johann Sebastian Bach had been a devout follower of Martin Luther, and he had certainly believed it, and then he had poured all the intensity of his belief into his music. It didn’t matter a damn whether he was right or wrong.

The rehearsal was over. Martin climbed up into the balcony and congratulated Barbara Inch. “The choir sounds wonderful. You certainly do a good job.” She seemed absurdly pleased.

He took Harold Oates aside. “Look, Harold, we’ve done our damnedest to work up a concert schedule for you, but you’re undercutting our best efforts. You can’t interrupt services. You can’t sleep all night in another church.”

Oates glowered at Kraeger. “Well, where the hell am I supposed to sleep?”

“Well, why not go home and sleep in your own bed?”

“Oh, shit, they threw me out of there. Lousy place, anyway.”

“They threw you out? Why did they throw you out?”

“Fire hazard. They told me I was a danger to public safety. Thought I’d burn down the house.”

“Fire hazard? What were you doing?”

“Repairing a four-foot pipe. It was Starr’s fault. He got the voicing stretched too far. I had to use a blowtorch to get it right. Curtains caught fire. My landlady blew a gasket, called the fire department, threw me out.”

“Well, damn it, Harold, now we have to find you another place. Listen, if you’re going to sleep in a pew, sleep here.”

Glumly he went back upstairs to his office to find Loretta Fawcett slapping down the mail on his desk. “I’m afraid some of this is old,” said Loretta. “I was so busy finishing my needlepoint pillow. You know, the broccoli. Now I’m starting the cabbage.” Loretta went back to her desk, and Martin sifted grimly through the mail.

It was the usual thing, appeals for the homeless, the starving, the addicted, the orphaned, the lost. This morning the wretchedness of the world’s condition fell on his shoulders like cobblestones. At the bottom of the pile he found a week-old letter from his ex-wife, and he winced. Kay didn’t write often, only when she wanted to announce some weird grotesquerie. This one was hard to figure out:

This time you’ve gone too far. I am going to sue.

What was that all about? Martin shrugged and threw the letter in the wastebasket. To his surprise, tears were brimming under his eyelids.