CHAPTER 50

I may compare the state of a Christian to a goose, tied up over a … pit to catch wolves.

Martin Luther

“What do you think,” Homer asked Mary, “should I slick down my hair and part it in the middle and wear thick glasses, like an undertaker in the movies?”

“No, no, they’d catch on right away. Undertakers don’t really look like that. They’re ordinary people. It’s a service industry, like running a garage or fixing teeth.”

Homer was ready for a day of body snatching. With the help of George Bienbower’s electronic home-publishing equipment he had acquired a piece of paper with the logo of a phony funeral home printed at the top. And then genial Boozer Brown had loaned him his hearse.

It was luxurious. The shock absorbers made a smooth ride, the engine was almost inaudible. Homer sang all the way to Boston about his merry Oldsmobile, although actually it was a Buick.

At the Mallory Institute of Pathology he drove into the parking lot and paused to scan the situation. Another hearse was standing beside a big open door. Homer thought it best to wait until it was gone, fearing the driver might engage him in shop talk. “Hey, fella, have you tried the Wozzick system yet? You know, the new way of congealing the vitals? Recommended in Mortician’s Monthly?” “Sorry,” Homer would have to say, flapping his hands, “I’m just transport. I deliver stiffs, that’s all. Don’t ask me.” But it would look bad. Homer turned off the engine and hid his face in the Boston Globe.

Not until the other hearse left the parking lot did Homer drop the newspaper and back Boozer’s limo around so that the rear end faced the door, which was now closed. He got out and rang the bell.

Someone flung up a window and said, “Just a sec, okay?” The window crashed down. An attendant in a green cotton jacket stood looking at him. “Who you here for?”

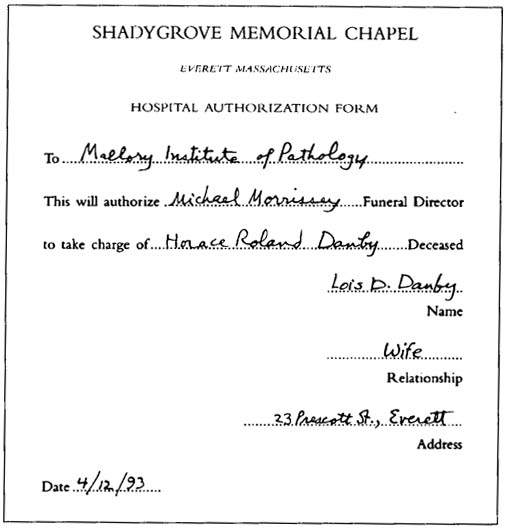

Homer looked at his phony release order. The name Horace Roland Danby had appeared in yesterday’s obituaries. Wordlessly he held out the piece of paper, which was artfully decorated with some of George Bienbower’s cleverest oversize fonts.

The attendant snatched the piece of paper and raced away down a sloping corridor, a long sad tunnel leading to the room where the bodies were stacked in refrigerated drawers. Homer had seen it. The room was windowless and lined with tile. He opened the back doors of the hearse and flicked a speck from the floor of the interior. Before long the attendant was back, rolling before him a gurney on which lay an object loosely wrapped in cloth. He brought it to a stop at the door and whisked another piece of paper out of his pocket.

Homer took it carelessly as though after tedious years of cadaver transport, glanced at it, scribbled his name at the bottom, and handed it back.

“Give me a hand, okay?” said the attendant.

“Oh, sure.” Homer got a grip on the wrapped feet. He was shocked by the chill, which sucked the warmth from his fingers. Shivering, he dropped the feet and backed away. “Look, never mind. I just wanted to find out if I could extract a corpse with phony papers. My name’s Kelly, Homer Kelly. I’m investigating a criminal matter.”

“Jesus Christ!” The attendant in the green jacket dropped the other end of the body, and it flopped back on the gurney. He snatched the release from his pocket and threw it at Homer. “Oh, God, don’t tell anybody. Jesus, don’t let my supervisor know.”

“Oh, don’t worry. It’s okay. This is a private investigation. I’m not part of any police department or anything like that.”

Without another word the attendant whirled the body around and raced back down the corridor, propelling the gurney before him in the dark satanic tunnel, pursued by all the devils of hell.

Homer drove away through the unlovely streets of Roxbury, remembering once again that the university where he taught and the suburb where he lived and the handsome streets of the Back Bay were merely a thin skim over the deep waters of the inner city. His unease was a typical sickness of the suburban soul in its genteel isolation from the dangers of urban life—We’re sorry, of course, really sorry, but it’s not our fault, is it? Well, maybe it is our fault, but we don’t know what to do about it, and anyway we’re busy. He drove for miles, gradually cheering up as countryside succeeded city, aware that his guilt would soon vanish.

At home he found his wife bowed over her books. “It worked,” he said, tearing off his jacket. “He swallowed it, the guy at the morgue. He handed over the body, never questioned a thing. I almost came home with it. We could have propped it in the yard like a piece of garden sculpture. The point is, somebody else could have swiped a body and nobody would have made a fuss. How do you like that?”

“Well, good for you,” said Mary, but she didn’t look pleased. “Homer, something else has happened. Charley’s disappeared. Alan called and told me. The baby’s gone.”

Homer gasped. For a moment they looked at each other, and then both of them said, “Rosie.”

Homer dumped his jacket on a chair and wrenched at his tie. “Well, there you have it, the doting mother after all. We’ve been wondering how she could endure being separated from her child, if she was alive. Well, now that’s no longer an issue.”

Mary slammed the book shut and stood up. She was wearing an old-fashioned pair of golfing knickers. “Exactly. Who else would kidnap a baby?”

“Oh, any number of people. Some young couple desperate to adopt a child. Or somebody in the business of supplying babies to couples like that. Or some affection-starved old lady on the street. They’re always extracting infants from baby carriages.”

“But Homer, Charley wasn’t snatched from a baby buggy. Somebody entered the foster mother’s apartment on Bowdoin Street and took him away, leaving Debbie’s little three-year-old behind—Debbie was AWOL.”

“Good Lord. So the next question is, how did Rosie know where to find him? That woman at Social Services, Mrs. Barker, she said people were phoning about him, only she wouldn’t ever tell them anything.”

“Maybe she finally did. I’ll call and find out. Maybe she’ll talk to me this time.”

“After lunch?” pleaded Homer. “I’ve been all over the East Coast this morning without a bite to eat. Take pity on a starving man.”

“Look in the fridge,” said Mary heartlessly. “There’s all kinds of stuff in there. Liverwurst, cheese. Take a look.”

When the phone rang in Mrs. Barker’s office, she was interviewing a pregnant teenager and the teenager’s mother. The mother looked more like the teenager’s sister.

“I want to keep the baby,” wept the teenager.

“An abortion, Sandra,” said her mother firmly. “You’re only fourteen.” She turned to Mrs. Barker. “Tell her. She’s only fourteen.”

The phone rang again. Mrs. Barker sighed and reached for it, staring at the mother and daughter. She felt like Solomon giving judgment. If she agreed with the daughter, another wretched child would be born into an unstable family to be reared in bad circumstances and end up a costly burden to the state. If she sided with the mother, a human being would be denied existence, and who could tell what sort of flower might have blossomed from this unlikely ground?

Mrs. Barker held the phone against her breast for a moment and closed her eyes, remembering a Right to Life poster she had seen somewhere, THE LIFE YOU SAVE MAY SAVE THE WORLD. It was sheer sentimental nonsense, but still—“Hello? Marilynne Barker speaking.”

“Mrs. Barker? My name’s Mary Kelly. My husband and I are investigating a recent case of kidnapping.”

“A kidnapping? What kidnapping?”

“Yesterday. A ward of the state was stolen from a foster mother named Deborah Buffington.”

“Oh, yes, of course. You mean Charley Hall.” Mrs. Barker shook her head despondently and looked at the fourteen-year-old in front of her, whose pink cheeks were trickling with tears. “That child has been a problem from the beginning.”

“Can you tell me, Mrs. Barker, whether or not you’ve given out his address to anyone recently?”

“Oh, yes, I’m afraid I have. Normally we never give out addresses unless we’re positive the person has some legitimate connection. I refused the information several times, but then when someone called claiming to be a doctor, I told him. Well, what could I do? He said the child was in danger of suffocating from a collapsed lung. Naturally I gave him the address. And next day the child was gone. I blame myself. Although I must say Deborah Buffington is a careless creature. We’ve crossed her off our list.”

“Do you know the name of the doctor?”

“Oh, it wasn’t a real doctor. The real doctor’s in Spain. The whole thing was just a ruse to get the baby’s location out of me. Unfortunately it worked.”

“Thank you, that’s a big help.”

Mrs. Barker returned to her clients. “Look, honey,” she said to Sandra, “I’m afraid your mother’s right. Wait till you’re a little older and can give a baby a proper family life. You should be enjoying yourself now, going to school and having fun with your friends.”

“You see, Sandra?” said her mother. “I told you, you’re too young.”

Sandra began to sob in earnest. “I want to keep the baby! I want to keep the baby!”

Mrs. Barker put her head in her hands and closed her eyes.