CHAPTER 51

… truth goes a begging.

Martin Luther

Coming from his apartment on Dartmouth Street, Martin always entered the church by the basement door on the alley. It had been painted royal blue as a welcome to the mothers and children of the daycare center, which now occupied the three bright rooms so recently brought to life by Donald Woody.

Through the open door of the biggest room came a babble of cheerful voices, the sound of small children singing. Kraeger nodded through the door at Ruth Raymond. To his surprise she glowered at him and turned her back.

Upstairs he found Barbara Inch rushing along the corridor. Seeing him, she stopped so quickly her hair swung forward and her skirt swirled around her knees. “Oh, good morning,” said Barbara.

Kraeger stopped too. “How are the Good Friday rehearsals coming along? What about Oates? Is he cooperating?”

Barbara grinned. “If I don’t watch out, he’ll steal the show.”

Kraeger took a shortcut through the kitchen, and there he had to stop and pass the time of day with Marian Beggs and Jeanie Perkupp, because they were old stalwarts who had been part of the congregation since long before his time. This morning they were preparing coffee and bouillon for newcomers.

“Oh, Martin,” said Jeanie, “I wish you’d try one of these macaroons.” She held out a plateful. “They came out a wee bit limp.”

Kraeger took one. “They taste fine to me. Delicious.” Then he had a thought. “How many macaroons have you people made for this church? I mean in all the years you’ve been coming here? And cookies and so on? Make a wild guess.”

There were protests and bursts of laughter as they tried to calculate. It turned out that Jeanie’s entire record was some thirty thousand, Marian’s forty-five.

“And if you took everybody else’s and added them in,” said Martin, “it would mount up to half a million. That’s what’s held this place together all these years, not bricks and mortar. Not those rock-solid pilings under the church. Macaroons, cakes and pies. It gives me an idea for a sermon.”

“Oh, Martin,” said Marian impulsively, “I want you to know I’m on your side.”

“So am I,” cried Jeanie.

Martin was surprised and pleased by these testimonials. But then his lifted spirits were dispelled by church treasurer Ken Possett, who was waiting for him in Loretta Fawcett’s empty cubbyhole outside his office. Loretta was taking her sick cat to the vet. “Oh, Martin,” said Ken gravely, “I’d like to speak to you.”

If Martin had a taskmaster in the congregation, an authority figure towering over him, it was Kenneth Possett. Ken was a sturdy old parishioner like Marian and Jeanie. He was one of the staunchest contributors to the budget, he had chaired many an annual canvass and moderated innumerable annual meetings. He had been head of the search committee that had chosen Martin Kraeger from a long list of applicants. As the congregation had changed in the last thirty years from a parish of wealthy local residents to a mixed and transient population of students, professionals, suburbanites and street people, Ken had kept up. He had even adapted to the idea of a Tuesday evening service for gays and lesbians, and a pastoring group for sufferers from AIDS. His wife Dulcie was another pillar of the church, and their children were active in the youth group. Ken had earned his authority, and Kraeger had often bowed to it in the past. This morning it nearly knocked him down.

“Of course,” he said, “come on in.” He pretended to unlock his door, because Ken would be shocked to think he ever left it open.

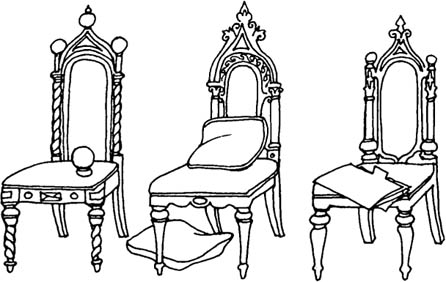

Ken sat down in one of the six massive chairs. He had bad news. An anti-Kraeger group, he said, was forming in the congregation.

“Oh,” said Kraeger, the light dawning, “is that what those two women were saying in the kitchen? They said they were on my side. You mean there’s another side?”

“I’m afraid so.” Ken looked at him solemnly and began listing their grievances. “First, the fire in the balcony that killed Mr. Plummer. You said it was your fault. Some people still hold a grudge.”

Kraeger’s bravado vanished. “Of course they do,” he said, wincing. “I don’t blame them.”

“Second, your support for Harold Oates, who is manifestly a dangerous vandal. A lot of people think he should be locked up, or at least no longer permitted to perform on our valuable new organ at sacred services.”

Kraeger opened his mouth in protest, but Ken held up another finger. “Third, political preaching. Some people complain there’s too much of it. They come to church for spiritual comfort, they say, not to be harangued.”

Kraeger smiled. This one was easy. “I cannot deny that I have been more vehement than is seemly. They ought not to have stirred up the dog.”

“What?”

“Martin Luther. That’s what he said when people told him he should stop shaking his fist at Leo the Tenth.”

Ken shook his head in warning. “It’s no joke, Martin.”

“Of course not. But all members of the clergy worth their salt run into the same thing.” For a moment a note of bitterness edged Kraeger’s voice. “There are people like that in every congregation. They want everything sunshiny. They don’t want to hear about other people’s problems. They don’t understand that the future is made out of wretched material”—Kraeger waved his arms and thought up crazy examples—“like lost hubcaps and sticky sandwich wrappers and mildewed Bibles and the disreputable causes of long-dead men and women.”

Ken stared at him blankly, and Kraeger went on wildly, reciting a hymn by James Russell Lowell about truth being forever on the scaffold and wrong forever on the throne, but fortunately it was the scaffold that swayed the future, because God was standing in the shadow keeping watch above his own. Then he shook his head sorrowfully. “The trouble is, maybe God isn’t keeping watch at all. Half the time the scaffold tumbles down and the hanged men fall into the pit and so do the women.” Kraeger stopped ranting, and made a gesture like brushing away a fly. “Listen, let those people who want spiritual solace go to Annunciation. Things are pretty soulful over there.” It was the wrong thing to say, and Kraeger knew it.

“Love it or leave it?” said Ken. “You don’t mean that, Martin?”

“No, of course not. But I’m not going to stop preaching the way I do. The soul isn’t some little closed-up walnut inside you. It’s part of a whole world of trouble.”

“Fourth”—Ken held up another relentless finger—“Dora O’Doyle. She has been identified. It seems she’s a notorious prostitute. You wrote out a check for nine hundred and fifty dollars to a prostitute.”

Kraeger stared at him, speechless. It came to his lips that it was not he who had engaged the woman’s services but Harold Oates, but he quelled the impulse just in time. It wouldn’t help matters to have another cause of complaint against Oates. “Look, Ken, you don’t think I’d pay a prostitute on a check labeled Church of the Commonwealth and have it turn up among your cancelled checks? It was supposed to be for Oates’s dental work, I tell you.”

“It did not reach the dentist.”

“No, that’s true. I paid the dentist’s bill a second time myself, later on. But at the time this woman told me she was the dentist’s accountant. Do you mean the whole congregation thinks I consort with prostitutes?”

“Fifth—”

“Oh, good God, what else?”

Ken spoke with extreme distinctness, separating the syllables. “Child mo-les-ta-tion.”

Kraeger laughed in disbelief. “What are you talking about?”

“Your former wife accuses you of molesting your daughter.”

“Pansy? She says I molested Pansy?” Kraeger laughed again. “You don’t really take that seriously?”

Ken spoke with distaste. “I don’t know anything about these things. But one reads about it in the papers. It seems to be fairly common.” Ken looked accusingly at Kraeger.

“But she’s only four years old. She’s my daughter. How could I do such a thing? What exactly does she say I’m supposed to have done to Pansy?”

Ken’s mouth worked. The details were apparently too repulsive to say aloud. “I think you’d better ask your ex-wife.”

Kraeger sat stricken in his chair, and Ken Possett said a grim goodbye. He did not say, “Carry on, old man,” or “We’ll work it out together,” and therefore Martin knew what a dangerous gulf had opened in his congregation. Was Ken Possett on the other side? If Ken were to come out against him, Martin Kraeger’s time at the Church of the Commonwealth would soon be finished.

Alone in his office, he fumbled blindly for the morning mail. Among the appeals for charity he found an envelope with a menacing return address, Pouch, Heaviside and Sprocket. With a sinking heart Kraeger recognized those pitiless extortionists, his wife’s divorce lawyers.

He tore open the envelope and found a summons to an arraignment for child molestation.

He called his ex-wife. “Kay, for heaven’s sake, what the hell are you doing? You know I never did a single damned thing to Pansy.”

“Oh, no? Well, Pansy and I know better. You’re an animal, a beast.”

“Oh, come on, Kay, be reasonable. I can’t believe this. What am I supposed to have done?”

“My attorney has instructed me not to speak to you on this or any other matter,” said his ex-wife, slamming down the phone.