CHAPTER 78

We must read, sing, preach, write, and compose verse, and whenever it was helpful and beneficial I would let all the bells peal, all the organs thunder, and everything sound that could sound.

Martin Luther

“Mary, dear, that’s a stunning outfit. What do you call it?”

“It’s my new persona. I made it. I’m going to make a lot of them. I’ve solved my wardrobe problem at last.”

“Well, it’s just great. Really majestic and African or maybe Greek. This is who you really are, is it? You reached down deep within yourself and fumbled around and decided this is what you’re all about?”

“Oh, no. I was just lazy. I took a huge piece of fabric and cut a hole in the middle and left openings for my arms in the side seams. That’s all. It’s not a big statement, or anything like that. But I’m never going back to being ladylike. Never in all this world.”

It had been a year since the collapse of the vaulting. The cycle of church life went on, even while the rubble was cleared away and new concrete pilings were driven down with the tremendous earsplitting noise of the pile driver ramming them into the ground. As the new walls went up within the shell of the old, the school auditorium continued to house the ceremonials of the Church of the Commonwealth. There were weddings and funerals and the welcoming of new parishioners.

Helen Tower was one of the new members. Alan and Rosie introduced her to the church, they took her to concerts and museums and the zoo, she played with Charley, she gossiped with Rosie. Then Mary Kelly found a cooperative residence for people with miscellaneous nerve disorders, and at last Helen was able to move out of her mother’s house.

It wasn’t easy. Mrs. Tower needed someone to be indebted day and night to her bitter sense of sacrifice, and she was reluctant to let Helen go. It took the assistance of Mrs. Barker in the Department of Social Services to pry Helen free.

“My God,” she said to Mary, “how long has this been going on?” And she signed her name to the document with a sweep of her hand.

For Mrs. Barker the rescue of Helen Tower was one of her small successes. There were so many failures! That same afternoon she experienced another disappointment while preparing to inspect a foster home on lower Washington Street. A young woman with a familiar face was leaning in a doorway, and Mrs. Barker recognized Deborah Buffington, although her childish features were almost obscured by thick eye makeup and lipstick, her thin fair hair was frizzed into a giant aureole, and her skinny midriff was bare above a shiny tight skirt.

“Why, Debbie, hello,” said Mrs. Barker. “Do you live in this neighborhood now?” But she knew with a sinking heart that this wasn’t where Debbie lived, it was where she worked.

Debbie glanced at her ferociously, and walked away on tottering heels.

Mrs. Barker rolled her eyes to the sky above lower Washington Street, which was a washed-out blue, empty of clouds, sun, moon, and God. “Just another botchup by the Department of Social Services,” murmured Mrs. Barker to herself, and then she began wondering what was happening to Debbie’s daughter Wanda. Oh, God, she’d have to find out about little Wanda.

The new Church of the Commonwealth was dedicated on a Sunday morning in May, only eighteen months after the collapse of the old building. James Castle played a tremendous prelude, Martin preached, Barbara’s choir sang at the tops of their lungs, and the congregation stared around at the plain white walls and the broad windows of clear glass. Some people were pleased, others were disappointed.

“It’s so cold,” said Bill Foose. “No stained glass, no carving, no decoration.”

“I miss the way it used to be so spiritual and medieval,” complained Melanie Chick. “Now it’s so modern.”

Ken Possett was irritated. “Well, at least,” he said, “it won’t fall down.”

After the service Martin and Barbara Kraeger invited the Kellys over for a drink. It was their first wedding anniversary. “And we want to show you something,” said Martin.

Mary was curious to see their place on Dartmouth Street. She had visited it once with Homer during Martin’s bachelor days, when it had been bleak and shabbily comfortable. Now she was amused to find it just the same. Barbara too seemed to have little interest in interior decoration. But she was a good cook. There were tasty hot things to go with their drinks.

“Delicious,” said Homer, gobbling half a dozen. “You know I have to confess, Reverend Kraeger, your church services leave me in a condition of mortal starvation. You provide food for the soul, I suppose, not for the body, is that it? Why don’t the ushers pass around trays of snacks every time you make a point, up there in the pulpit? Now, tell us, what are we here to see?”

Martin grinned at him. “Walter Wigglesworth’s book. They found it in the cornerstone of the old building when they cleared out the last of the rubble.”

“Behold!” said Barbara. She heaved a large box onto the table and lifted the lid.

“Good heavens,” said Mary. “There it is, Divine Inspiration, just like the book in the painting.”

“Yes,” said Martin. He stroked the cover. “The painting’s torn to shreds, but at least we’ve got the book.”

“Well, what do you think?” said Homer eagerly. “Is it really inspiring? Is it full of spiritual secrets, you know, from one clergyman to another?”

“Oh, it’s inspiring, all right.” Barbara laughed. “See for yourself.” She lifted the heavy book and dumped it carefully in Mary’s lap.

Mary turned the pages slowly. “Oh, dear, I’m afraid it’s mostly Ella Wheeler Wilcox and James Gates Percival and Edith Matilda Thomas. How disappointing.” She shook her head, and dropped the book onto Homer’s knees.

Homer too was stunned. “Seated one day at the organ, I was weary and ill at ease, and my fingers wandered idly over the noisy keys—My God, I’d forgotten all about ‘The Lost Chord.’ You know, Martin, somehow I don’t think this stuff is quite right for you.”

“Well, apparently it was just right for Walter Wigglesworth. One glance at his precious book and glory descended.”

“I guess the moral is,” said Barbara, “one person’s inspiration is another person’s—”

“Hogwash,” suggested Homer.

“Crap,” offered Mary.

Martin laughed. “So what am I going to do for inspiration now? I’ll have to go right back to the Bible and all my old standbys.”

“Henry Thoreau might come in handy now and then,” suggested Homer primly.

“Oh, sure, and Jim Castle’s music, naturally, but the trouble with music is, you can’t take out a tidy quotation and repeat it in the middle of a sermon.”

“No, that’s right,” said Homer. “Music just gives you a sort of general unspecified, amorphous, inchoate jolt of something sort of shapeless and unorganized and vague and—”

“But sometimes,” objected Barbara, “it can be ecstatic and organized at the same time. I mean—”

“Right,” said Martin, “it’s the language of the soul, sort of. It’s not something you can put into words. It’s really kind of—”

“Wonderful,” said Mary, “and of course you can put words to it, and then sometimes even the dumbest words are transformed into something that’s really—”

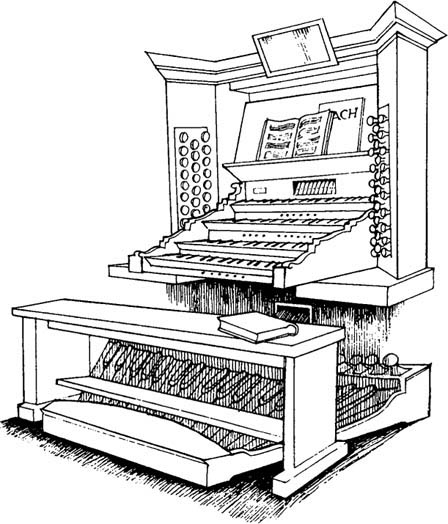

They gave up trying to define the inspirational nature of music. It didn’t matter. Whatever it was, the organ from Marblehead provided it in the rebuilt Church of the Commonwealth, Sunday after Sunday, with its two thousand seven hundred and sixty pipes of wood and metal.

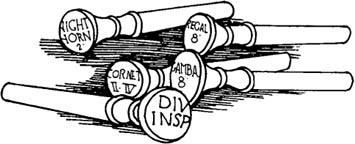

Castle called it glory, and perhaps it was. At any rate the Contra Bombarde bawled and bellowed, the Rohrpipe hooted, the Cymbal squealed, the Trumpets blared their fanfares, the eight-foot Diapason did the solid work of holding it all together in a harmony, perhaps, of the spheres, and the DIV INSP stop knob continued to be connected to nothing, to nothing on earth at all.