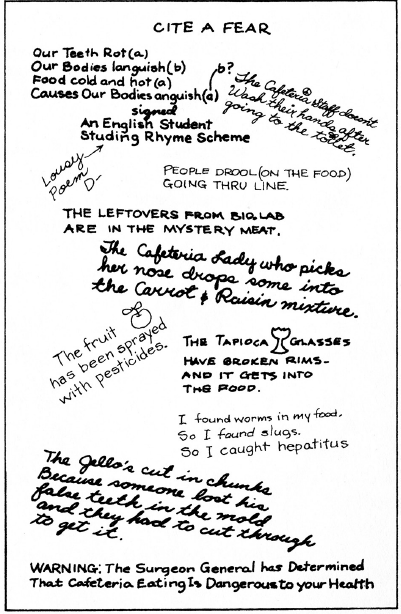

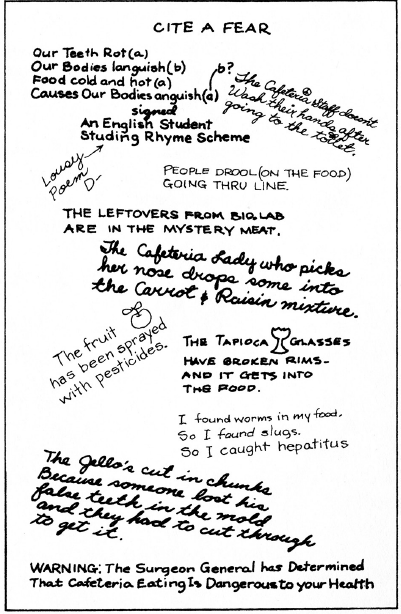

That’s as far as CITE A FEAR got. We put up a large piece of brown paper on the wall by the cafeteria entrance, and the kids started writing on it.

Beasley pulled it down. He also gave detention to one kid he caught writing on it, Pete. Pete wrote the terrible poem but he shouldn’t have gotten detention. He got the rhyme scheme almost right.

Personally I think that Pete carried the protest a bit too far, lying down on the floor and yelling stuff like, “I regret that I have but one life to give for my stomach.” “Don’t shoot till you see the whites of their bread.” And “Ask not what your food service can do for you—but what you can do for your food service.”

Anyway now he’s a martyr for the cause. He’s got two days of detention and has to write a poem apologizing.

The boycott’s working. Only about ten kids cross the cafeteria line.

We were going to have picket lines and carry signs but decided that we could get into trouble for that, and there was no need to do it.

Not buying food was enough. The cafeteria was stuck with about eighty billion hot dogs (you know the kind—they float them in water with little globs of grease) and beans (the pale orange ones with watered-down sauce). Some of the stuff they could freeze, but a lot of it they couldn’t.

It’s really wasteful to throw it away with people starving in the world, but I’m sure they’d die of malnutrition from our cafeteria food anyway.

The cafeteria workers come out, look at all the kids eating homemade lunches, and shake their heads.

Beasley walks in, looks like he’s going to say something but doesn’t, and storms out.

We go on with our classes, but somehow cafeteria is what everyone focuses on, the kids at least.

Some teachers ignore the whole thing. Others like Mr. Cohen, the Civics teacher, use it to teach us history or literature. They talk about Henry David Thoreau, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr., all people who protested without use of violence.

The boycott goes on for three days.

My father and I continue to make extra lunches.

My mother calls every night, and I try to tell her what’s going on, but she’s kind of wrapped up in her own problems and just wants me to listen.

I try not to think about her too much and try to concentrate on the boycott. That’s a lot easier to deal with.

It’s fun. We all trade our lunches with each other. Some of the kids are bringing great food. I eat tofu, alfalfa sprouts, and mung bean salad. And a sandwich made of pickled herring and radishes. Never again will I eat a sandwich like that.

By the end of the third day Beasley makes an announcement over the loudspeaker.

“All students willing to work on a committee to change school menus are invited to a meeting next Tuesday night. Interested parents are also invited. Please plan to buy lunches again. We will do our best to serve food that meets your requests, within reason.”

The cheering can be heard all over the school.

We won the battle, fair and square.

Nobody really even lost, because the food will be better for everyone.