No other city in Europe underwent such massive physical transformations in the 20th century as Berlin. Given a new shine around 1900, as the capital of the German Empire, the city was devastated in World War II, and then divided into two for nearly 45 years, a victim and a symbol of the Cold War. West Berlin was a capitalist outpost, with a sometimes tacky prosperity and wild nightlife; east of the Berlin Wall that ran across the middle of the city, the austere standards of the Communist bloc prevailed. Economic growth in both sectors attracted large immigrant communities: mostly Turks in the west, mostly Vietnamese in East Berlin.

Since the Wall came down in 1989 and Berlin was again declared capital of a united Germany an enormous amount has been spent on rejuvenating and unifying the city once again. Grand old museums in the former eastern sector have been lavishly renovated – making this one of the most museum-rich cities in Europe – and formerly run-down districts in the east have become newly fashionable, their old-style architecture and prices (still often lower than those further west) attracting artists, students and people working in the creative industries. Most of the Wall has been deliberately swept off the map. Making Berlin one integrated city, though, has been complicated, and plenty of traces of its disjointed personality remain, which all adds to its fascination.

One of the most striking things about modern Berlin is that it still has two – or even three – centres. In the east, on Alexanderplatz, the Fernsehturm (TV tower; daily), the city’s tallest structure and once the emblem of the “capital of the GDR”, marks the historical centre of Berlin – Berlin-Mitte – and the former hub of East Berlin. To the west, the blue Mercedes Star affixed to the Europa-Center marks the location of the Kurfürstendamm, the bustling heart of the western part of the city. And, in between, is the shiny modern architecture of the new shopping and entertainment centre around Potsdamer Platz, rebuilt from top to bottom since 1989.

The Reichstag.

Jon Santa Cruz/Apa Publications

Known locally as the Ku’damm, Kurfürstendamm, which means “The Electors’ Road”, used to be just a broad track leading out to the country, a bridle path for the bluebloods who rode out towards the forest at Grunewald to go hunting. Only with Germany’s rapid industrial expansion after 1871 did the street begin to take shape. Inspired by the Champs-Elysées in Paris, Bismarck decided that he wanted such a boulevard for the new capital of the Reich. Building work proceeded in “Wilhelmine” style: generous, ornate and florid, truly representative of the age.

By the 1920s, Kurfürstendamm had become the place where everything considered bohemian was on offer. The street was all but wiped from the map in World War II but, during the post-war years, it became a symbol of the prosperity of West Berlin and again acquired a dazzling nightlife. On the night following the collapse of the Wall, it was to Ku’damm that most East Berliners flocked.

At the eastern end of Ku’damm is Breitscheidplatz, with the ruins of the neo-Gothic Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche 1 [map] (Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church; daily) and its blue-glazed modern incarnation, raised in the 1960s amid the bomb-blasted ruins. A popular meeting place in summer is the Weltkugelbrunnen (1984), a vaguely globe-shaped fountain next to the Europa-Center 2 [map] shopping complex, with a huge range of shops, restaurants, bars and a noted cabaret theatre, the Stachelschweine. A lift goes up 20 storeys to a viewing platform. On nearby Wittenbergplatz is the stylish Kaufhaus des Westens (Department Store of the West), known as the KaDeWe, the only one of the city’s great department stores to survive World War II bombing.

Close by (Ku’damm 18–22) is the Neues Kranzler Eck mall (2000), a Helmut Jahn high-rise, with offices, stores and a wide plaza housing an aviary. The new complex incorporated older 1950s buildings, including the Café Kranzler, one of West Berlin’s most famous cafés in the Cold War era of the 1960s and 1970s. It’s now reduced to a smaller space, in the second-floor rotonda, but still has some of its 1950s decor. Behind the Zoologischer Garten station, on Jebensstrasse, the Museum für Fotografie (Museum of Photography; Tue–Sun) holds the Helmut Newton Collection, the legacy of the renowned photographer who died in 2004, and hosts excellent temporary shows.

In the side streets, called Off-Ku’damm, are some of the better restaurants, cafés and pubs; the city has more than 8,000 places to eat and drink. Close by, on Lehniner Platz, stands the avant-garde Schaubühne, a theatre built in the expressive style of the 1920s.

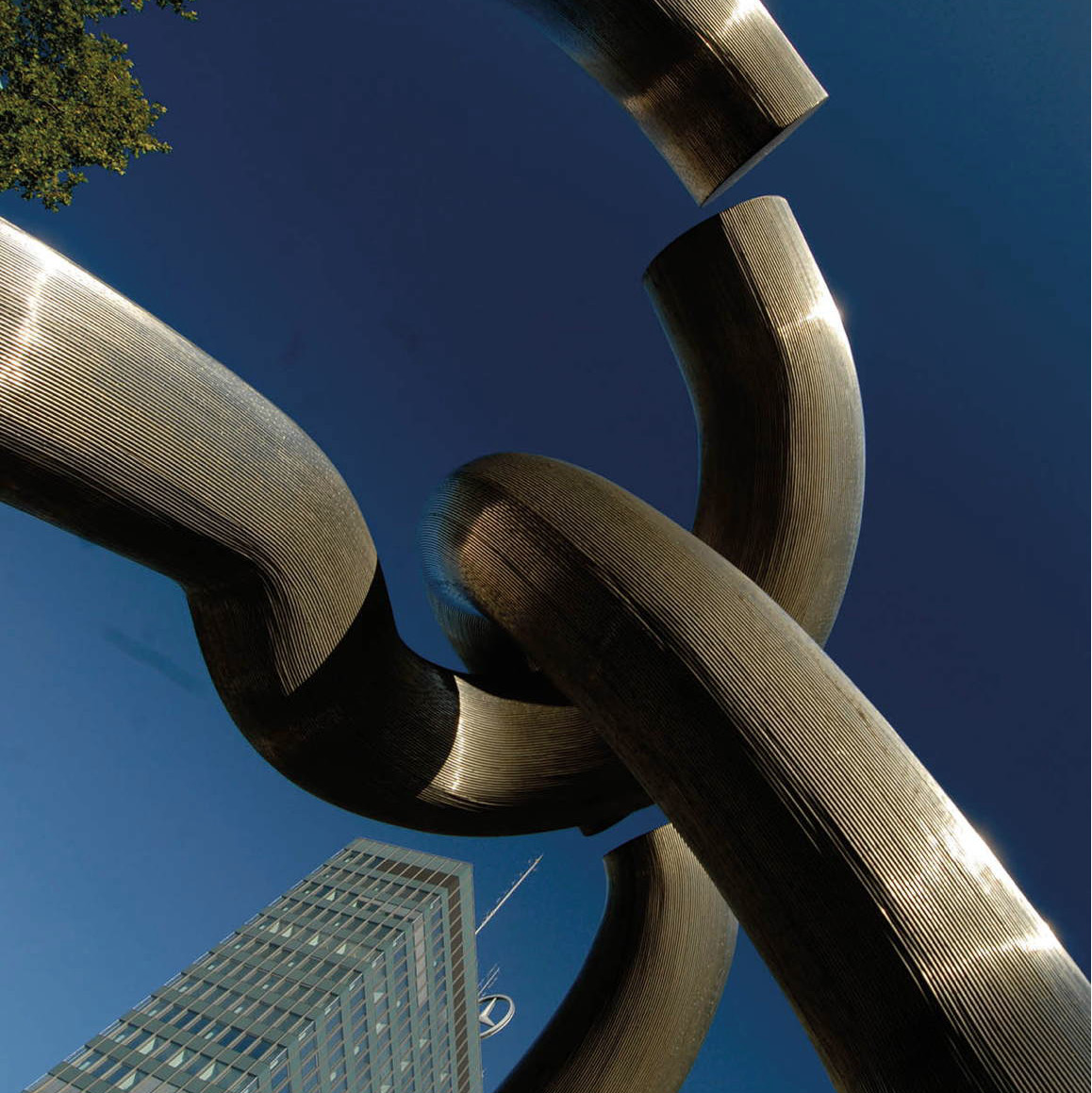

The Berlin Sculpture.

Tiergarten and the Culture Forum

In the middle of the city is the 212-hectare (525-acre) Tiergarten, a wonderful park where many Berliners spend time at weekends. The Zoo Berlin 3 [map] (daily) is in its westernmost corner. One of the largest in the world, it is home to around 14,000 animals. In the centre of the Tiergarten, the 67-metre (223ft) Siegessäule or Victory Column 4 [map] was built in 1873 to commemorate the Prussian victory over the Danes in 1864. From here there is a grand view down to the Brandenburg Gate.

Tip

In a city with such a complex and changing history as Berlin, tours with guides who really know its obscure corners are particularly useful. New Berlin Tours (www.newberlintours.com) offer a very popular free walking tour and others on particular subjects such as the Alternative scene or “Red Berlin”. Insider Tours (www.insidertour.com) include Jewish Berlin, the Third Reich and the Cold War among their themes.

Just south of the Tiergarten, the Kulturforum is dominated by the Philharmonie 5 [map] concert hall, home of the Berlin Philharmonic. Designed in geometric, modern style in the 1960s to replace an older hall destroyed in 1944, the Great Hall is famous for its superb acoustics, and the building also contains the Kammermusiksaal for chamber-music recitals. There are also several major museums in the Kulturforum (all Tue–Sun), among them the Musikinstrumentenmuseum, with more than 2,500 musical instruments; the Neue Nationalgalerie 6 [map] (New National Gallery), Mies van der Rohe’s minimalist glass-and-steel structure, which displays the work of Kokoschka, Dix, Picasso, Léger, Magritte and many other modern artists; and above all the Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery), one of the world’s finest collections of European art from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, which showcases masterpieces by Dürer, Cranach, Brueghel, Vermeer, Caravaggio and Rembrandt.

The Kulturforum stands just west of Potsdamer Platz 7 [map]. Under the Weimar Republic this was one of the great hubs of Berlin, the busiest traffic junction in Europe and the location of the most opulent hotels and department stores. The division of 1945, however, cut straight across the giant square, and its conversion into a desolate wasteland was confirmed when the Wall was laid across it in 1961. It was here that important guests such as US presidents were brought to see the Wall, from a special viewing platform. Consequently, after reunification Potsdamerplatz became the foremost centre of projects to rebuild and reunite Berlin, Europe’s largest and most prestigious development site. Now unrecognisable from its 1989 emptiness, the square is ringed by sleek, ultra-modern giant buildings by famous contemporary architects, such as the Daimler-Benz complex by Renzo Piano and Richard Rodgers. The Panoramapunkt (daily) on the 24th floor of the Kolhoff Tower building is a viewing platform from where you can marvel at the scale of reconstruction in the new Berlin.

On the eastern edge of the Tiergarten is the Reichstag 8 [map], built in the late 19th century in Neo-Baroque style, which is once more home to Germany’s national parliament, the Bundestag. Damaged by the infamous Reichstag Fire in 1933, the building was a primary target of Soviet troops as they advanced into Berlin in 1945. By the battle’s end the interior was completely gutted, although the massive outer walls still stood. During the years of division it was only partially restored. Then, after reunification, it was comprehensively rebuilt to a design by British architect Norman Foster, with an entirely new structure inside the original walls. Its most striking feature is the spectacular glass dome, with a spiral ramp from where visitors can watch parliamentary proceedings, leading up to a roof garden with great views across Berlin (daily; advance booking required).

Children at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Former East Berlin

Since its inauguration in 1791, the Brandenburger Tor 9 [map] (Brandenburg Gate), between the Tiergarten and central Berlin’s grand boulevard, Unter den Linden, has been a symbol of the fate first of Prussia, then of Germany. Napoleon marched through it on his way to Russia, and sent back to Paris the gate’s crowning ensemble, the Quadriga (the goddess Victory on her horse-drawn chariot). In 1814, the Quadriga was brought back in triumph by Marshal Blücher. Kings and emperors paraded here; the revolutionaries of 1918 streamed through it to proclaim the republic; and it was where the Nazis staged their victory parades. After 1945 it stood on the line between East and West Berlin.

After the Wall came down, the Gate became a symbol of the hopes of a united Germany, and is again the favoured setting for public events. New York architect Peter Eisenman’s striking Holocaust memorial, a vast “field of stelae” titled the Denkmal für die Ermordeten Juden Europas (Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe) ) [map] lies to the south of the gate.

The Berlin Wall

For a quarter-century (1963–89), the Berlin Wall was the city’s grimly defining feature. Today, virtually nothing of it is still standing. Visitors who want to see what little remains can visit important stretches along Niederkirchnerstrasse, between Potsdamer Platz and Checkpoint Charlie; along Spree-side Mühlenstrasse, at the East Side Gallery, in the Friedrichshain district; and along Bernauer Strasse, in Mitte. None of these gives the complete picture of the Wall, with its death-strip, watchtowers and surprising depth, but they do afford a small insight into what it was like. Elsewhere, there are some odd bits and pieces here and there, and a line of double cobblestones running through the city, in some places supplemented by memorial plaques, shows where the once formidable barrier stood.

Beyond the Gate you enter former East Berlin. Immediately on the other side is Pariser Platz, another square that has been thoroughly rebuilt with emphatically modern structures such as the DZ Bank, by US architect Frank Gehry. The Hotel Adlon, one of the city’s most historic hotels, was also rebuilt. The most Prussian of Berlin’s streets, Unter den Linden, lined with linden (lime) trees, leads east from here towards the heart of Old Berlin, Berlin-Mitte.

Curiously, East Berlin contained much of the city’s grandest architecture. The imposing Neoclassical structures of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841) around Unter den Linden testify that Berlin was once among the most beautiful of European cities. Some maintain that the Schauspielhaus theatre on the Gendarmenmarkt ! [map] is Schinkel’s finest building, and the square is aesthetically perfect. Others say the Neue Wache (New Guard House) on Unter den Linden is Schinkel’s best. Since 1993 this building has been the Central Memorial of the German Federal Republic for the Victims of War and Tyranny, and contains an enlarged version of the bronze Pietà, from 1937, by Käthe Kollwitz.

On the left (going east) are the monumental buildings of the Staatsbibliothek (State Library) and the Humboldt University. Opposite the university, in the old Opern Platz, now Bebelplatz, the Nazis burnt 20,000 books in 1933. The square, planned by Frederick the Great, is graced with splendid structures. There is the Baroque Zeughaus @ [map], the old arsenal, now the Deutsches Historisches Museum (daily), covering German history from earliest times; the Staatsoper (Opera House) directed by Daniel Barenboim, the Alte Bibliothek (Old Library) and St Hedwig’s Cathedral, modelled on the Roman Pantheon, combine to create a harmonious architectural masterpiece.

Tip

The website www.museumsinsel-berlin.de has information in both German and English on how the master plan for the museums on Museum Island is progressing; visit www.smb.museum for information on special exhibitions, opening times and charges at all Berlin’s major public art museums.

Museum Island

Museumsinsel £ [map] (Museum Island) is one of the world’s finest museum complexes, with collections that include everything from ancient artefacts to early 20th-century art. Before 1989 its five museums were neglected; some had not been restored since World War II. This is another part of Berlin that has received massive attention since reunification, and visitors benefit from long-drawn-out renovation programmes that are only now coming to fruition, and in some cases will not be entirely finished until 2015. It requires a day, at least, to visit all the museums (all open Tue–Sun).

The Altes Museum (Old Museum) is another of Schinkel’s masterpieces. Its Neoclassical rooms house superb Greek, Roman and Etruscan antiquities, in a new display unveiled in 2011. The Pergamon Museum contains one of Berlin’s most remarkable treasures, a section of the Pergamon Altar (180–159 BC), controversially taken from the ancient Hellenic city in Turkey after excavations in 1878. The museum also has large Islamic collections. The Bode-Museum, with late Roman and Byzantine art, is in a splendidly restored building next to the River Spree, but one of the island’s jewels is the Neues Museum (New Museum, though it first opened in 1855). This had been virtually a ruin since 1945, until another comprehensive reconstruction project was begun, incorporating the remains of the original building, under British architect David Chipperfield. It now provides a stunning setting for its celebrated Egyptian and ancient artefacts, especially a famous bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti.

Lastly, the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery) was the first building on Museum Island to be renovated (1998–2001). Its impressive collection of 19th–20th century paintings is particularly strong in German artists like Caspar David Friedrich or Max Liebermann, but also includes French artists such as Manet.

Just south of Museum Island is Berliner Dom $ [map] (Berlin Cathedral), built in 1894 as “the chief church of Protestantism”.

New Berlin

Around Mitte are the once shabby districts of former East Berlin that became centres of alternative culture in the 1990s, and are now being gentrified. The neighbourhood around Hackescher Markt and north into Prenzlauer Berg is now one of the liveliest in the city, with a thriving art scene and cafés, restaurants and clothes shops. On Oranienburger Strasse, the Neue Synagoge % [map] was the grandest Jewish temple in Europe when it was built in 1866. Almost destroyed by Nazi attacks and World War II bombing, it was extensively renovated in the 1990s and now again houses a functioning synagogue and the Centrum Judaicum (Jewish Centre; Sun–Fri) museum. To the northwest on Invalidenstrasse is the most cutting-edge of Berlin’s post-reunification museum schemes, the Hamburger Bahnhof-Museum für Gegenwart ^ [map] (Museum for the Present; Tue–Sun), the former Hamburg railway station, transformed into a dynamic space for the showing of contemporary art by figures such as Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol and Anselm Kiefer, as well as spectacular temporary exhibitions.

Kreuzberg, south of Mitte, is known as a rough-and-ready district that has also been a centre of the immigrant – mainly Turkish – communities, the punk and radical music scene, and gay Berlin. As in other old districts, this bohemian atmosphere had led it to become more gentrified and upmarket in recent years. Within it is one of the great must-sees of modern Berlin, the stunning Jüdisches Museum & [map] (Jewish Museum; daily). In an extraordinary jagged-walled building by architect Daniel Libeskind, the museum presents 2,000 years of Jewish history in highly imaginative displays, with immensely powerful memorials to the Holocaust. A tunnel leads to a lovely green space, the Garden of Exile.

Charlottenburg Palace, built in the 18th century.

Jon Santa Cruz/Apa Publications

Charlottenburg

West of the city centre is the impressive Baroque Schloss Charlottenburg * [map] (Charlottenburg Palace; daily). Built in 1695 as a country house for Sophie Charlotte, grandmother of Frederick the Great, it was extended in the 18th century. Across from the beautiful palace grounds are the Bröhan Museum (Tue–Sun), a lovely collection dedicated to Art Nouveau, Art Deco and other early 20th-century decorative arts, and the Berggruen Museum, a modern art gallery currently closed for restoration.