Falcon

(魔)

The Chinese designate eagles, falcons, and other raptorial birds by the term yïng, the written symbol for which on analysis is found to be a representation of one bird swooping down upon another.

“The Emperors of the Mongol Dynasty were very fond of the chase, and famous for their love of the noble amusement of falconry, and Marco Polo says Kublai employed no less than seventy thousand attendants on his hawking excursions. Falcons, kites and other birds of prey were taught to pursue their quarry, and the Venetian speaks of eagles trained to swoop at wolves, and of such size and strength that none could escape their talons.”87

These predatory birds provide a popular ornamentation for screens, panels, etc, and are regarded as emblematic of boldness and keen vision.

The Chinese have a superstitious belief that medical benefit is derived from the feathers of the tail, with which they rub children suffering from smallpox as a curative charm.

In the feudal age of China falcon-banners styled yú (旗) were borne in the chariots of the higher chieftains, and in parts of Turkestan to this day a living hawk is carried as emblem of authority.

Fan

(扇)

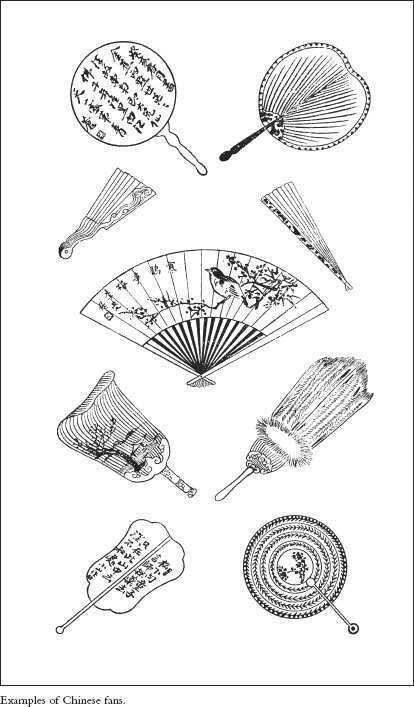

Fans have been used in China from ancient times; the round variety was popular in the Táng period, but the ordinary folding article (揺扇) was a Japanese invention introduced into China through Korea in the 11th century A.D. They are made in many different styles and form an excellent medium for the display of the artistic spirit of the Chinese. Circular fans are made of silk, paper, feathers, and from the leaves of púkuí (蒲藥) or Livistonia chinensis, a palm-tree grown in the lowlands of South China. Folding fans have horn, bone, ivory, and sandalwood frames. Ornamental varieties of mother-o’-pearl, tortoiseshell, lacquer, etc., command the highest prices.

The fan is carried in the sleeve or waistband, and besides its ordinary use, is also employed to emphasize special points of a speech, or to trace out characters in the air when the spoken word is not understood. “As there is fashion in all things, so fashion has decreed that women are to use one sort of fan, and men another. It lies principally in the number of ribs in the fans. A man’s fan may contain 9, 16, a very favourite number being 20 or 24 ribs, but a woman’s fan must not contain less than 30 ribs. Feminine figures may be freely introduced in the decoration of fans for women, but it would be considered in bad taste for an adult male to be seen with a fan with such decoration.”88 Different kinds are used at different seasons by all who can afford to pay for this form of luxury; and it is considered ridiculous to be seen with a fan either too early or too late in the year. They are made to serve the same purpose as an album among friends of a literary turn, who paint flowers upon them for each other and inscribe verses in what is sometimes called the “fan language.”89

“Fans are used in decorative art; papers for fans are printed, mounted, and framed as pictures; open-work spaces are left in walls of the shape. Even the gods and genii are sometimes represented with these indispensables of a hot climate, some of them being capable of all sorts of magic.”90

The fan is the emblem of Zhōnglí Quán (鍾離權), one of the EIGHT IMMORTALS (q. v.) of Taoism. A deserted wife is often metaphorically referred to as “an autumn fan” (秋後扇), since fans are laid aside at the end of summer.

Many of the artistes of the Sòng and later dynasties were fond of painting miniature landscapes and floral studies on fans. The handles of fans, i. e., the outer ribs, were also decorated with paintings and carvings; the wood for these handles was carefully selected. The hard surface of the bamboo made it a general favourite, but other rarer woods were also employed, especially those with a fine grain. Generally one surface of a fan and handle was embellished with painting, and the other with a specimen of fancy calligraphy. Thus a fan may display all the distinguishing characteristics of artistic production.

Feng Shui

(風水)

Feng Shui lit., wind and water, i. e., climatic changes said to be produced by the moral conduct of the people through the agency of the celestial bodies, is the term used to define the geomantic system by which the orientation of sites of houses, cities, graves, etc., are determined, and the good and bad luck of families and communities is fixed. The dousing-rod and the astrological compass are employed for this purpose. It is the art of adapting the abodes of the living and the graves of the dead so as to co-operate and harmonize with the local currents of the cosmic breath, the YIN AND YANG (氣 q. v.). By means of talismans and charms the unpropitious character of any particular topography may be satisfactorily counteracted. “It is believed that at every place there are special topographical features (natural or artificial) which indicate or modify the universal spiritual breath (qì). The forms of hills and the directions of watercourses, being the outcome of the moulding influences of wind and water, are the most important, but in addition the heights and forms of buildings and the directions of roads and bridges are potent factors. . . . Artificial alteration of natural forms has good or bad effect according to the new forms produced. Tortuous paths are preferred by beneficent influences, so that straight works such as railways and tunnels flavour the circulation of maleficent breath. The dead are in particular affected by and able to use the cosmic currents for the benefit of the living, so that it is to the interest of each family to secure and preserve the most auspicious environment for the grave, the ancestral temple, and the home.”91

The Feng Shui system is said to have been first applied to graves by Guō Pú (郭撲), a student who died in A.D. 324, and to house-building by Wáng Jí (王仮), a scholar of the Sòng Dynasty.“For a grave, a wide river in front, a high cliff behind, with enclosing hills to the right and left, would constitute a first-class geomantic position. Houses and graves face the south, because the annual animation of the vegetable kingdom with the approach of summer comes from that quarter; the deadly influences of winter from the north.”92

The symbolic figures, etc., on the roofs of buildings, the pictures of spirits on house doors, and the stone images erected before the tombs, are chiefly for the purpose of producing an auspicious aura in which the cosmic currents may generate for the creation of favourable Feng Shui for the benefit of the locality. (Vide also ASTROLOGY, CHARMS, DOOR GODS, DRAGON, etc.)

Fire

(火)

The written symbol for fire is a pictogram (像形) representing a flame rising in the centre with sparks on either side. It is used as the 86th radical for the formation of characters connected with light and heat.

Fire is emblematic of danger, speed, anger, ferocity, lust, etc., and is the second of the FIVE ELEMENTS (q. v.). The planet Mars is called the Fire Star (火星). The fierce Buddhist deities have their halo bordered by flames.

At Chinese New Year (過年), and also at the Feast of Lanterns (燈節), many beautiful coloured lanterns are to be seen, and numerous fire-crackers are exploded. The latter festival is held on the 15th of the 1st moon and dates from the Hàn Dynasty some two thousand years ago, being originally a ceremonial worship in the Temple of the First Cause (元始天尊).

Fire-crackers, Roman candles, Catherine wheels, rockets, etc., are made of crude gunpowder rolled up in coarse bamboo paper, with an outer covering of red—the colour of good omen. They are chiefly made in Hunan, Kiangsi, and Kuangtung. A feu de joie of squibs and cannon crackers is believed to disperse evil influences, especially when fired off in batches of three, one after the other; no doubt the three crackers are for the propitiation of the THREE PURE ONES (q. v.), or in honour of the Star-Gods of Health, Wealth, and Longevity. Fire-crackers are employed at all kinds of ceremonies, religious and otherwise, and are exploded as a farewell compliment on the departure from the locality of a popular person or a government official.

Crude gunpowder (火藥) has been manufactured by the Chinese since the seventh century, but was originally used only for fireworks. Guns, which were invented in Europe in A.D. 1354, were used in China from A.D. 1162. Cannon were employed by the Mongols in A.D. 1232. The Chinese hunter often fires from the hip, and generally uses a long muzzle-loading fowling-piece of antique pattern.

Effigies made of coloured paper are burnt at the grave-side in the hope that they will be translated into the spirit world for the assistance of the manes of the dead. These effigies replaced the original sacrifices of human beings and domestic animals formerly offered in connection with the honours paid to deceased celebrities.

The bride, on entering the house of her husband, is sometimes lifted over a pan of burning charcoal, or a red-hot ploughshare, laid on the threshold of the door by two women whose husbands and children are living. It is thereby intimated that she will pass successfully through the dangers of child-birth.

Fires are not generally used in Chinese houses except for cooking, but a brick stove-bed (坑), with a fire underneath, is used in the north. The source of illumination employed by the poorer classes is bean oil and candles made of white wax or vegetable tallow. The use of kerosene oil is now fairly general, and electric light has been installed in many places, though the plant is often very much overloaded and the current correspondingly weak. When lamp-posts were first erected in Shanghai the innovation was regarded as a harbinger of evil to the dynasty. If a “flower” forms on a burning lamp-wick, it may, according to its shape, imply that the wife is with child, that a guest is coming, or that someone is about to die. A couple of lanterns to hang at the gate or a pair of large red candles are considered to be auspicious gifts at a wedding, implying that the yáng (陽) or active principle of light will operate for the generation of plenteous offspring on behalf of the happy pair.“The candles in the bride’s room are supposed to burn all night; if one or both goes out it is a bad omen, foretelling the untimely death of one or both; on the other hand, if the candles burn out about the same time, it indicates that the couple will have the same length of life, and the longer the candles burn, the longer will the couple live. The candles must not melt and trickle down the sides, or that would resemble tears and be-token sorrow.”93

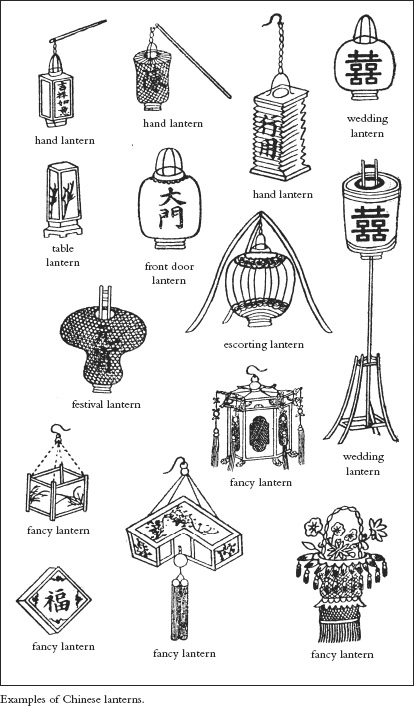

Lanterns play a prominent part in the social and religious life of the people.“Some of the lanterns are cubical, others round like a ball, or circular, square, flat and thin, or oblong, or in the shape of various animals, quadruped and biped. Some are so constructed to roll on the ground as a fire-ball, the light burning inside in the meanwhile; others as cocks and horses, are made to go on wheels; still others, when lighted up by a candle or oil, have a rotary or revolving motion of some of their fixtures within, the heated air, rising upward, being the motive power. Some of these, containing wheels and images, and made to revolve by heated air, are ingeniously and neatly made. Some are constructed principally of red paper, on which small holes are made in lines, so as to form a Chinese character of auspicious import, as happiness, longevity, gladness. These, when lighted up, show the form of the character very plainly. Other lanterns are made in a human shape, and intended to represent children, or some object of worship, as the Goddess of Mercy, with a child in her arms. Some are made to be carried in the hand by means of a handle, others to be placed on a wall or the side of a room. They are often gaudily painted with black, red, and yellow colours, the red usually predominating, as that is a symbol of joy and festivity. The most expensive and the prettiest are covered with white gauze or thin white silk, on which historical scenes, or individual characters or objects, dignified or ludicrous, have been elaborately and neatly painted in various colours. Nearly every respectable family celebrates the feast of lanterns in some way, with greater or less expense and display. It is an occasion of great hilarity and gladness.”94 “It is the frequent practice for people to make specific vows in regard to burning a lamp before some particular god or goddess, in a temple dedicated to the divinity, for a month or a year, for the night time only, or both day and night, during the period specified. They usually employ the temple keeper to buy the oil and trim the lamp. Sometimes people prefer to vow to burn a lantern before the heavens. The lantern is usually suspended in front of the dwelling-house of the vower. In such a case, it is trimmed by himself or by some member of his family. Many also make vows to the ‘twenty-four gods of heaven,’ or to the ‘Mother of the Measure,’ writing the appropriate title upon the lantern they devote to carrying out their vows.

“On the occurrence of the birthday of the god or goddess, the family generally presents an offering of meats, fish and vegetables. On the first and fifteenth of each month they regularly burn incense in honour of the divinity, whose title is on their lantern, before the heavens. The objects sought are various, as male children, recovery from disease, or success in trade.”95 (Vide also GOD OF FIRE, and THUNDERBOLT.)

Fish

(魚)

“Fish forms an important part in the domestic economy of the Chinese. Together with rice it constitutes the principal staple of their daily food, and fishing has for this reason formed a prominent occupation of the people from the most ancient times. The modes of fishing and implements used at the present day vary very little from those of the remote past; the simplicity of the former and the ingenious construction of the latter are as remarkable now as in days gone by. That fishing should be engaged in so extensively is easily explained. The coast line is long and tortuous; groups of islands, forming convenient fishing stations, are spread all along the mainland; swift streams and large lakes intersect the country, and a net of canals water the vast plains in all directions. All these circumstances serve to direct the attention of the people to the exploration of the waters. On the part of the Government no restrictions are laid on fishing grounds. Fishing is carried on all the year round, and no regulations hamper the fishermen in the use of their nets or lines; but each fishing boat must be registered where it belongs, and at fixed periods must pay a fee for a licence. A tax is also required for the privilege of fishing in the rivers and canals, space being allotted to each party in proportion to the payment made. During the spawning season fishing is not interdicted in the inland waters, and even on the high sea fishermen continue their operations—but with this difference, that smaller nets are made use of during this intermediary period than during the regular fishing season.”96

The commonest kinds of fish that serve as food in China are the carp, bream, perch, plaice, “white fish,” “blue fish,” mullet, pomfret, Sciaenidae fish, rock trout, scabbard fish, and eel. Crabs, shrimps, lobsters, oysters, clams, cockles, bêche-de-mer, cuttle fish, sea blubber, molluscs, turtles, etc., are also eaten. In fact, fishery products such as sharks’ fins, compoy, awabi, dried shrimps, and other similar preparations, are among the chief delicacies of the Chinese table. Some interesting details of the Chinese fisheries and methods of fishing are given in the Bulletin of the Chinese Government Bureau of Economic Information (經濟討論處), No. 25, Series 2, March 23, 1923, and also in the Author’s article “The Ningpo Fisheries,” in the New China Review, 1919, Vol. IV, pp. 385 seq.

From the aesthetic point of view fish are also much appreciated by the Chinese. Many beautiful and fantastic varieties of gold fish are reared in ponds and jars, this ornamental species having been introduced into Europe towards the end of the seventeenth century. Carp and perch are frequently depicted on Chinese porcelain.

The legendary Emperor Fú Yì (伏義), 2953–2838 B.C. is said to have been given his name, which means literally “Hidden Victims,” on account of the fact that he made different kinds of nets and taught his people how to snare animals and secure the products of the sea.

The fish is symbolically employed as the emblem of wealth or abundance, on account of the similarity in the pronunciation of the words yü (魚), fish, and yü (餘), superfluity, and also because fish are extremely plentiful in Chinese waters. Owing to its reproductive powers it is a symbol of regeneration, and, as it is happy in its own element or sphere, so it has come to be the emblem of harmony and connubial bliss; a brace of this is presented amongst other articles as a betrothal gift to the family of the bride-elect on account of its auspicious significance; as fish are reputed to swim in pairs, so a pair of fish is emblematic of the joys of union, especially of a sexual nature; it is also one of the charms to avert evil, and is included among the auspicious signs on the FOOTPRINTS OF BUDDHA (q. v.). “The fish signifies freedom from all restraint. As in the water a fish moves easily in any direction, so in the Buddha-state the fully-emancipated knows no restraints or obstruction.”97 The Buddhists consider great merit (福) accrues to those who release living creatures (放生) such as birds, tortoises, etc., bought for the purpose at religious festivals. A tank containing carp or gold-fish is generally to be found in the temple courtyard. “From the resemblance in structure between fish and birds, their oviparous birth, and their adaptation to elements differing from that of other created beings, the Chinese believe the nature of these creatures to be interchangeable. Many kinds of fish are reputed as being transformed at stated seasons into birds.”98 (Vide PENG NIAO).

The carp, with its scaly armour, which is regarded as a symbol of martial attributes, is admired because it struggles against the current, and it has therefore become the emblem of perseverance. The sturgeon of the Yellow River are said to make an ascent of the stream in the third moon of each year, when those which succeed in passing above the rapids of lóngmén (龍門) become transformed into dragons; hence this fish is a symbol of literary eminence or passing examinations with distinction.

According to the BO GU TU (q. v.), fish are compared to a king’s subjects, and the art of angling to that of ruling. Thus an unskilled angler will catch no fish, nor will a tactless prince win over his people.

On account of various legends that letters have been found in the bellies of carp, etc., the fish is also an emblem of epistolary correspondence.

Five Elements

(五行)

The Five Elements are Water (水), Fire (火), Wood (木), Metal (金), and Earth (土). They are first mentioned in the classic Book of History (vide Legge: Shu Jing, II, 320, note). They are mutually friendly or antagonistic to each other (相生相勉) as follows:

Water produces Wood, but destroys Fire;

Fire produces Earth, but destroys Metal;

Metal produces Water, but destroys Wood;

Wood produces Fire, but detroys Earth;

Earth produces Metal, but destroys Water.

“Upon these five elements or perpetually active principles of Nature the whole scheme of Chinese philosophy, as originated in the 洪範, or Great Plan of the Shü Jïng, is based. The latter speculations concerning their nature and mutual action are derived from the disquisitions of Zōu Yân (驟衍) followed by the 五行志 of Liú Xiàng (劉向) and the 白虎通義 of Bān Gù (班固).”99

From the operation of the five elements, proceed the five atmostpheric conditions (五剩), five kinds of grain (五穀), five planets (五星), five metals (五金), five colours (五色), five tastes (五味), etc., each of which is governed by its appropriate element, and should not be rashly mixed together or disaster will ensue. The TEN CELESTIAL STEMS (q. v.) are also influenced by the elements.

“According to Zhú Xï, the five elements are not identical with the five objects whose names they bear but are subtle essences whose nature is however best manifested by those five objects.”100

The Spirits of the Five Elements are known as the Five Ancients (老五), who are also regarded as the Spirits of the Five Planets.

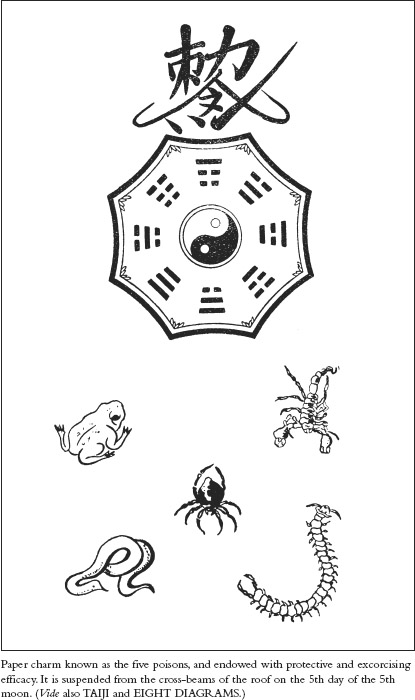

Five Poisons

(五毒)

The five poisonous reptiles, viz, the viper, scorpion, centipede, toad, and spider, a powerful combination which has the power to counteract pernicious influences. “Sometimes images of these reptiles are procured, and worshipped by families which have an only son. Pictures of them are often made with black silk on new red cloth pockets, worn by children for the first time on one of the first five days of the fifth month. It is believed that such a charm will tend to keep the children from having the colic, and from pernicious influences generally. They are often found represented on the side of certain brass castings, about two inches in diameter, used as charms against evil spirits.”101

A Tincture of the Five Poisons (五毒藥酒) is concocted by putting centipedes, scorpions, snakes, and at least two more kinds of venomous creatures into samshu. It is prescribed in catarrh, coughs, ague, and rheumatism. This potent spirit is placed in earthenware jars outside the shops of the well-to-do traders, to be taken by poor persons as a prophylactic remedy.

“The lizard (嫩虎) is sometimes included in the category of five poisonous insects. It is known as the Protector of the Palace for the following reason. If lizards are fed on vermilion and their tails cut off, and the blood of the latter rubbed on the wrists of the ladies of the harem, it can be proven whether they are virtuous or not. If they are virtuous the blood will not come off; if not, the blood will wash off! Perhaps this method was purposely devised by the eunuchs to frighten the ladies of the harem. In South China it is believed that if a lizard loses its tail—by casting—and the tail enters a person’s ears, that person will become deaf. In the North it is believed that if one takes a lizard’s tail and rubs it between the palms of the hands the latter will not perspire. And, worst of all, a lizard can crawl into the ear of a sleeping person and suck his brains! It is also believed that if a house-lizard comes into contact with food, it leaves a poisonous substance that will cause death.”102

Five Viscera

(五臓)

The Five Viscera are the HEART, LIVER, STOMACH, LUNGS and KIDNEYS (q. q. v.). They represent the emotional feelings (vide IDOLS, MEDICINE), and are said to be governed by the FIVE ELEMENTS (q. v.) as follows:

| FIVE VISCERA: | CORRESPONDING ELEMENTS: |

| Heart | Fire |

| Liver | Wood |

| Stomach | Earth |

| Lungs | Metal |

| Kidneys | Water |

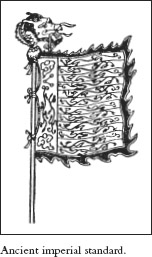

Flags

(旗)

Gay coloured standards, pennons, and streamers, have always been popular with the Chinese, who, like the Romans of old, were formerly accustomed to worship their military flags and banners.

According to the ancient “Book of Ceremonies” (禮記), “On the march the banner with the Red Bird should be in front; that with the Dark Warrior behind; that with the Azure Dragon on the left; and that with the White Tiger on the right; that with the Pointer of the Northern Bushell should be reared aloft in the centre of the host—all to excite and direct the fury of the troops.” (行前朱鳥後玄武,左 青龍, 而右白虎 ° 招搖在上, 急績其怒).103 Vide DRAGON, PHOENIX, TIGER, and TORTOISE.

From the Hàn to the Qïng Dynasty the Imperial coat of arms consisted of a pair of dragons fighting for a pearl, and the National Flag (國旗) was emblazoned with the device of the five-clawed dragon in variegated colours with the red sun or jewel on a yellow ground. At the inauguration of the Republic, however, the use of the imperial dragon as a national emblem was discontinued and the Republican Flag was devised. This was a five-coloured flag (五色旗), the different coloured bars being emblematic of the Five Clans (五族), viz.:

red for Manchuria, yellow for the Chinese,

blue for Mongolia, white for the Mohammedans, and black for Tibet. This flag was flown over government buildings, and two crossed Republican flags were depicted on official noticeboards (招牌) in place of, as formerly, the tiger’s head design. The present national flag, introduced in 1928, consists of a red field with a white sun on a blue ground in the left top quarter. Long embroidered banners, Sanskirt, Dvaja, are employed in processions of a religious nature.

There was a movement for the independence of Manchuria early in 1932, and the flag designed for the use of the new state, Manchukuo (滿州國), has four stripes of red, blue, white, and black in a square at the upper right hand corner, signifying bravery, justice, purity, and determination respectively, while the yellow ground symbolises unification.

Flowers

(花)

An extraordinary devotion to flowers has prevailed from early ages among the Chinese, who are skilled horticulturists. The flowers of blossoming trees, appearing at the end of winter on the leafless branches, are particularly cultivated. Many flowering plants are said to have originated in China. The Emperor Wû Dì (武 ), of the Hàn Dynasty, established a botanical garden at Zhângān in 111 B.C. In planning a garden the Chinese is actuated by the desire to reproduce as closely as possible the innumerable natural scenes so dear to the heart of a refined scholar. Hills, streams, and bamboos are essential features. The best site is an uncrowded part of the city, near the wall, so that the garden will contain some rising ground on which winding paths may be constructed and pavilions erected at suitable points of vantage. Ornamental rocks of grotesque shape are much admired, and stunted trees are planted here and there, while shady pools containing lotus flowers and gold-fish, and spanned by miniature bridges with carved balustrades, are also desirable.

), of the Hàn Dynasty, established a botanical garden at Zhângān in 111 B.C. In planning a garden the Chinese is actuated by the desire to reproduce as closely as possible the innumerable natural scenes so dear to the heart of a refined scholar. Hills, streams, and bamboos are essential features. The best site is an uncrowded part of the city, near the wall, so that the garden will contain some rising ground on which winding paths may be constructed and pavilions erected at suitable points of vantage. Ornamental rocks of grotesque shape are much admired, and stunted trees are planted here and there, while shady pools containing lotus flowers and gold-fish, and spanned by miniature bridges with carved balustrades, are also desirable.

Artificial grottoes and rounded openings in walls, with suitable mottoes engraved or painted above them, are often to be seen. There are many historic gardens in China. Soochow, Hangchow, and Wusih are famous for gardens of great beauty. There is a celebrated garden in Shanghai known as the Yú Yuán (愚園), or Garden of Ease, in which are pavilions, terraces, rocks, and pools. A Chinese garden generally occupies a small space in comparison with western gardens, with their extensive lawns, wide herbaceous borders, and elaborate parterres. It is not considered correct to monopolise too much ground, as it might be more economically utilized for purposes of agriculture—the most important business of life.

Each flower in China has its appropriate meaning and purpose. The principal varieties are treated separately in this glossary, and their emblematic significance is also fully dealt with.“It is currently believed that every woman is represented in the other world by a tree or flower, and that consequently, just as grafting adds to the productiveness of trees, so adopting a child is likely to encourage a growth of olive branches.”104

The Taoist Goddess of Flowers is known as Huā Xiān (花仙). She is generally represented accompanied by two attendants carrying baskets of flowers (花藍). The flower-basket is the emblem of Lān Câihé (藍采和), one of the EIGHT IMMORTALS (q. v.) of Taoism. A festival of flowers is held in certain parts of China on the 12th day of the 2nd moon.“The women and children prepare red papers, or silk favours of various colours, and on the appointed day suspend them on the flowers and the branches of flowering shrubs. The women and children then recite certain laudatory and congratulatory sentences, and prostrate themselves. By this worship it is supposed that a fruitful season can be assured.”105 “The head-dress of married females is becoming, and even elegant. In the front, a tube is often inserted, in which a sprig or bunch of flowers can be placed. The custom of wearing natural flowers in the hair is quite common in the southern provinces, especially when dressed for a visit. The women of Peking supply the want of natural by artificial flowers.”106 Ornamental pots containing artificial flowers made of paper, silk, or jewels of various colours with leaves of green jade are sometimes seen in Chinese houses.

A common term for China is the Flowery Land (花國). The floral kingdom supplies the Chinese with many of their finest designs in decorated textiles, porcelain, carpets, etc. Representations in flowers in architecture, painting, etc., are often so highly conventionalized, and the colouring so untrue to nature, that it is often difficult to determine the particular species intended. They are drawn as viewed from above, in accordance with the general rules of art. A particular flower is almost invariably drawn with a particular bird. Thus the longtailed birds such as the phoenix, peacock, fowl and pheasant have the peony; the duck, the lotus; the swallow, the willow; quails and partridges are generally depicted with millet; the stork and pine, as emblems of longevity, naturally go together. The bamboo, pine, and prunus are known as the three friends, because they keep green in cold weather, and are therefore frequently grouped together. Various flowers and fruit blossoms are often used to symbolize the twelve months of the year, e. g., in the following order: prunus, peach, peony, cherry, magnolia, pomegranate, lotus, pear, mallow, chrysanthemum, gardenia and poppy. The following have been selected to represent the four seasons: the tree-peony for spring, the lotus for summer; the chrysanthemum for autumn; and the prunus for winter. (Vide also TREES, and separate notices of various flowers and trees.)

Flute

(笛)

The dí or transverse flute, is “a bamboo tube bound with waxed silk and pierced with eight holes, one to blow through, one covered with a thin reedy membrance, and six to be played upon by the fingers.”107 Another variety of flute, known as the xiāo (蕭), is of “dark brown bamboo, measuring about 1.8 foot in length, said to have been invented by Yē Zhòng (耶仲) of the Hàn Dynasty. It has five holes above, one below, and another at the one end, the other end being closed.”108

The flute is the emblem of Hán Xiāngzî (韓湘子), one of the EIGHT IMMORTALS (q. v.) of Taoism, and sometimes of Lán Câihé (藍采和), another of that ilk. The marvellous skill with which Xiāo Shî (蕭史)—6th century B.C.—performed upon this instrument, accompanied by his wife Nōng Yù (弄玉), is said to have “drawn phoenixes from the skies.” (Vide MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS.)

Fly-whisk

(塵尾)

Sanskrit, Chauri. Properly made of the tail of the yak, Tibetan ox (梨牛), but also composed of white horse hair or vegetable fibre, fixed to a short handle of plain or carved wood, and carried by the Buddhist priests as a symbol of their religious functions, and to wave away the flies which, according to the tenets of their creed, they may not kill. As the herd of deer was said to be guided by the movements of the yak’s tail, so the sages of China are often depicted with this sign of leadership, and it is an item of the paraphernalia of Buddhism and Taoism. It is also called 塵土拂 or 拂繩.

Buddha said: “Let every Bhikchu have a brush to drive away the mosquitoes.”“In Buddhism it signifies obedience to the first commandment—not to kill. In Taoism it is regarded as an instrument of magic. Its origin is India. Many Buddhist images are represented holding it.”109

Footprints of Buddha

(佛足跡)

When Buddha felt, in 477 B.C., that the time of his Nirvana (淫樂)— the state of complete painlessness which was his highest goal—was approaching, he went to Kusinara and stood upon a stone with his face to the south. Upon this stone he is said to have left the impression of his feet, Sanskrit, S’ripada, as a souvenir to posterity. These impressions were subsequently reproduced in carved stone and religious paintings, and may be met with in temples in India, China, and Japan. A stone marked with Buddha’s footprint is preserved in the Tiāntāi Monastery (天台寺), which is situated on the Western Hills near Peiping. On the footprints are various emblematic and auspicious designs sacred to Buddhism; they are known as the SEVEN APPEARANCES (七相) (q. v.). The stone bearing the footprints, also known as the “Buddha-foot stone,” is not always cut out of a single block of stone, but is sometimes composed of fragments cemented together in an irregular shape and capped with a heavy slab of granite, on the polished surface of which the design is engraved.

In some cases, on the instep is a triple Lotus (Tri-râtna, or “Three Treasures”), which springs from a Triscula or Trident, which rests on a small mystic Wheel (Châkra) on the heel, and symbolizes the Three Buddhas of Past, Present and Future, i. e., AMITÂBHA, KUAN YIN and MAITREYA (q. q. v.). The Vinâya-sutra says that the marks on the sole of Buddha’s foot were made by the tears of the sinful woman, Amrapati and others, who wept at Buddha’s feet, to the indignation of his disciples.

Four Heavenly Kings

(四大天王)

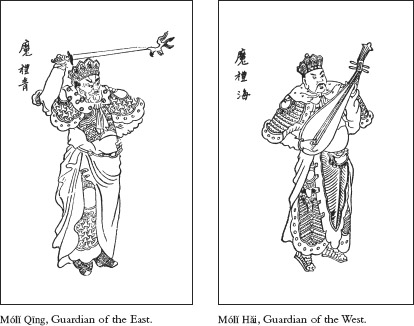

The Heavenly Guardians or Deva Kings, Sanskrit, Chaturmaharajas or Lokapalas, the Kuvera of Brahamanism, were four Indian brothers. They are also called the Diamond Kings (四大金剛). “These four celestial potentates are fabled in later Buddhist tradition as ruling the legions of supernatural beings who guard the slopes of Paradise (Mount Meru), and they are worshipped as the protecting deities of Buddhist sanctuaries. Bù Kōng (不空)—a Cingalese Buddhist, is said to have introduced their worship in the 8th century A.D.”110 They protect the world against the attacks of evil spirits, and their statues, gigantic in size, are to be seen at the entrance to Buddhist temples, two on each side.

“They stand each on the prostrate body of an evil demon—alert and ready to ward off all vices and wickedness which might threaten the men of faith and the countries where righteousness prevails; and in the powerful muscular tension of face, body, and limbs, the invincible will and tireless energy of each are vigorously portrayed.”111 Their names and characteristics are as follows:

1. The Land-Bearer (持國), Skt. Dhrtarãstra (提頭賴托), Guardian of the East; also called Mólî Qïng (魔禮青). He has a white face, with a ferocious expression, and a beard the hairs of which are like copper wire. He carries a jade ring, and a spear. “He has also a magic sword, Blue Cloud, on the blade of which are engraved the characters dì, shuî, huô, fēng (Earth, Water, Fire, Wind). When brandished it causes a black wind which produces tens of thousands of spears, which pierce the bodies of men and turn them to dust. The wind is followed by a fire, which fills the air with tens of thousands of golden fiery serpents. A thick smoke also rises out of the ground, which blinds and burns men, none being able to escape.”112 He is the eldest of the four Kings.

2. The Far Gazer (廣目), Skt. Virûpaksha (耻樓博乂), Guardian of the West; also called Mólî Hâi (魔禮海). He has a blue face and carries a four-stringed guitar, at the sound of which all the world listens and the camps of his enemies take fire.

3. The Lord of Growth (增長), Skt. Virûdhaka (耻樓博乂), Guardian of the South; also called Mólî Hóng (魔禮紅). He has a red face and holds an umbrella, called the Umbrella of Chaos, formed of pearls possessed of spiritual properties. At the elevation of this marvellous implement universal darkness ensues and when it is reversed violent thunder-storms and earthquakes are produced.

4. The Well-Famed (多聞), Skt. Vaisravana (耻沙門), Guardian of the North; also called Mólî Shòu (魔禮壽). He has a black face and “has two whips and a panther-skin bag, the home of a creature resembling a white rat, known as Huahu diao. When at large this creature assumes the form of a white-winged elephant, which devours men. He sometimes has also a snake or other man-eating creature, always ready to obey his behests.”113 He also carries a pearl in his hand.

There is a Taoist quartette of these deities named Li, Ma, Chao, and Wên, who are represented as holding a pagoda, sword, two swords, and a spiked club, respectively. They are said to have given military assistance to the Emperor at various times during the Táng and Sòng Dynasties.

Four Treasures

(四寶)

The four precious articles, or “Invaluable Gems” (無價之寶) of the literary apartment (文房), i. e., ink, (墨) paper (紙), brush-pen (筆), and ink-slab (硬).

Chinese ink in solid form—erroneously called Indian ink—decorated with all manner of symbolic devices, is chiefly made in Anhui of lampblack mixed with varnish, pork fat, musk (or camphor), and gold-leaf. Besides being used for writing the Chinese character, believed to be of mystic and sacred origin (vide WRITTEN CHARACTERS), if rubbed on the lips and tongue it is considered a good remedy for fits and convulsions.

Paper, which was originally fabricated from the bark of trees and the cordage of old fishing-nets, is now made from rice-straw, reeds, wood-pulp, rags, etc. It is said to have been originally invented by Caìlún (蔡倫), a native of Guìyáng (桂陽). Chief Eunuch under the Emperor Hé Dì (和帝), of the Eastern Hàn Dynasty; he died in A.D. 144, and was canonised as the god of the paper-makers, who worship him on his birthday. So useless did this strange invention seem to the people of that remote age that, use what means he might, Caïlún was unable to find a market for his discovery; he therefore eventually had recourse to a deception which proved so successful that not only did he establish a demand for his production, but also formed the precedent for a custom which has been universally observed throughout the country. Caïlún consented to feign death and, no doubt after the proper ceremonies had been carried out, was duly buried. Lest he should actually die and ruin his scheme, a hollow bamboo pole was struck in the ground over his mouth through which he could still breathe. When his friends and neighbours were all assembled they were told that if the “money” made of the despised paper was burnt at his grave they might buy back his life. When a sufficient amount was deemed to have been thus consumed he was exhumed and his living body shown to the astonished mourners. When, some years later, Caïlún actually died, he was counted a rich man, and the belief that imitation paper “money” burnt over the grave will buy back life, if not for another spell in this world, at least as a spirit in the next, of the departed, has been held throughout the land from his day to this. Paper images and charms are burnt to him on his birthday. Paper images and charms are burnt to the souls of the dead, and paper amulets against disease are often set on fire, and the ashes taken in wine or tea for curative or demon-expelling purposes (vide CHARMS).

Mêng Tián (蒙括) is credited with the introduction of the Chinese brush-pen, which is made of sable, fox, or rabbit hairs, set in a bamboo holder. He died in 209 B.C., and is worshipped on his birthday by the pen-makers as their patron saint. The written paper is carefully burnt by devout persons.

The ink-slab is made of stone or paste, and is used for triturating the solid ink, and thus preparing it for writing purposes. It contains a well for the water, into which the ink is dipped before rubbing it on the stone to form a writing fluid. Ink-slabs are often beautifully carved, and some are made from ancient bricks stamped with the builder’s date (vide WATER POT).

Fowl

(雞)

The fowl is the tenth symbolic animal of the TWELVE TERRESTRIAL BRANCHES (q. v.). Its various designations 燭夜, 司晨, etc., mostly refer to its crowing, which is said to be regularly all through the day as well as at dawn. The Chinese pay special and superstitious regard to the crowing of cocks, while the crowing of a hen is believed to indicate the subversion of a family and is an emblem of petticoat government.

The flesh of the male bird is said to be injurious, probably on account of the fact that the cock is used in oaths and sacrifices and is not to be slain on ordinary occasions. Blackboned fowls are called yàojï (藥雞) and are much prized for making soup for persons suffering from consumption and general debility. Cordial, tonic and many other fanciful properties are accorded by the Chinese to the yolk and albumen of the egg, which they compare to the sky and the soil of the universe, respectively. A kind of pepsine is prepared from the gizzard, called 雞 金 or 肺皮. Many distinctions are made between the colour and sex of the birds, as to their suitability, or otherwise, for particular kinds of diseases. Preparations of the male bird are prescribed for female patients, and vice versa.

金 or 肺皮. Many distinctions are made between the colour and sex of the birds, as to their suitability, or otherwise, for particular kinds of diseases. Preparations of the male bird are prescribed for female patients, and vice versa.

The cock (公雞) is the chief embodiment of the element yáng (陽), which represents the warmth and life of the universe. It is supposed to have the power of changing itself into human form, to inflict good or evil upon mankind. The Chinese ascribe five virtues to the cock. He has a crown on his head, a mark of literary spirit; and spurs on his feet, a token of his warlike disposition; he is courageous, for he fights his enemies; and benevolent, always clucking for the hens when he scratches up a grain; and faithful, for he never loses the hour. The picture of a red cock is often pasted on the wall of a house in the belief that the bird is a protection against fire. As ghosts disappear at sunrise, the cock is supposed to drive them away by his crowing; hence a white cock is sometimes placed on the coffin in funeral processions to clear the road of demons.“The Chinese say that one of the three spirits of the dead comes into the cock at the time of meeting the corpse, and that the spirit is thus allured back to the residence of the family. Some explain the use of a purely white cock to the exclusion of any other coloured cock on such occasions, by saying that white is the badge of mourning; others, by saying that the white cock is a ‘divine’ or spiritual fowl.”114 No doubt, however, its white colour is emblematical of purity of heart. It was the custom for the bride and bridegroom to eat white sugar cocks at the wedding ceremony.“A white cock is said to be a protection against baneful astral influences and to be the only capable guide of transient spirits. In this connection one is reminded of a custom observed by modern Jews, viz., the substitution of a cock for the scape-goat as a means of expiation. The sins of the offerer are said to be transferred to the entrails of the fowl, and these are exposed upon the house-top, to be carried away by birds of the air.”115 Cock-fighting (闘雞) was practised in China some five hundred years ago.

A cock and a hen standing amid artificial rock-work in a garden of peonies is a common pictorial design symbolizing the pleasures of a country life. A fowl on the roof of a house is regarded as a bad omen, and it is very unlucky it is thunders while a hen is sitting on eggs.

Fox

(狐涯)

The fox, especially Vulpes tschiliensis, is very common in North China. Canis hoole is found in South China, Canis corsac in Mongolia and Vulpes lineiveenter in the mountains of Fukien. Foxes are sometimes seen emerging from old coffins or graves in the country, and are, therefore, regarded as the transmigrated souls of deceased mortals.

“The fox is a beast whose nature is highly tinged with supernatural qualities. He has the power of transformation at his command, and frequently assumes the human shape. At the age of 50 the fox can take the form of a woman, and at 100 can assume the appearance of a young and beautiful girl, or otherwise, if so minded, of a wizard, possessing all the power of magic. When 1,000 years old, he is admitted to the Heavens and becomes the ‘Celestial Fox.’The Celestial Fox is of a golden colour and possesses nine tails; he serves in the halls of the Sun and Moon, and is versed in all the secrets of nature. The Shuōwēn Dictionary states that the fox is the courser upon which ghostly beings ride; he has three peculiar attributes, viz., in colour he partakes of that which is central and harmonising (i. e., yellow); he is small before and large behind, and at the moment of death he lifts his head upwards. The 名山記 states that the fox was originally a lewd woman in times of old. Her name was Zî (紫) and for her vices she was transformed into a fox.”116

“The superstition about demons appearing in a form something like a fox (狐涯精) is very wide-spread. The creature has a man’s ears, gets on roofs, and crawls along the beams of houses. It only appears after dark, and often not in its own shape but as a man or beautiful girl to tempt to ruin. Numberless stories of the foxes as girls are found in light literature. People live in great fear of them, and immense sums of money are expended to keep on good terms with them by offerings, incense, meats, tablets, etc. They often possess a man, who then commits all manner of extravagances and claims to be able to heal disease. Some wealthy people ascribe all their good fortune to their careful worship of the fox.”117 No doubt these magic powers were ascribed to the animal on account of its cunning and stratagem. The fox is regarded by the Chinese as an emblem of longevity and craftiness.

Wayside shrines, dedicated to the fox, are often found in the country, and this creature is believed to be acquainted with all the secret processes of nature he is invoked both for the cure of disease, and also as god of wealth. The clay images of the fox-spirit in the shrines are generally in the shape of a richly-dressed official with a fox-like cast of eye, accompanied by his wife, a pleasant-looking elderly lady.

“Foxes are regarded as uncanny creatures by the Chinese, able to assume human shapes and work endless mischief (chiefly in love affairs) upon those who may be unfortunate enough to fall under their spell. In some parts of China, it is customary for mandarins to keep their seals of office in what is called a ‘fox chamber’ (狐仙模); but the character for fox is never written, the sight of it being supposed to be very irritating to the live animal. A character 胡, which has the same sound, is substituted; and even that is divided into its component parts 古 and 月, so as to avoid even the slightest risk of offence. This device is often adopted for the inscriptions on shrines erected in honour of the fox.”118 “In the course of official business, a great number of documents are accumulated in the archives of the Yamen. Sometimes these are urgently required and the person in charge is unable to find them. He then lights some sticks of incense and prostrates himself beseeching the help of the fox god. Shutting up all the windows and doors, he leaves the room for a time. Returning after an interval he will find, it is said, thanks to the kindly help of the fox god, one volume or packet sticking out beyond the others; this will be the manuscript or volume he is in search of.”119

Many interesting fox legends are to be found recorded in Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, by Professor H. A. Giles, who obtained his material from the Liao Zhai Zhi Yi, written by Pu Songling in the 7th century A.D.

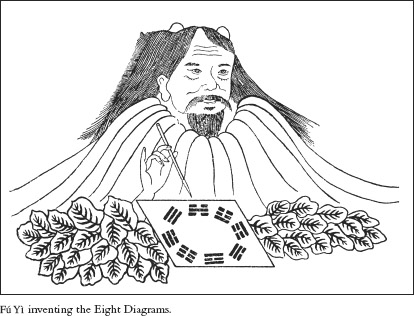

Fú Yì

(伏義)

2953–2838 B.C. The first of the Five Emperors of the legendary period, also known as 包義氏 and 太吴.

He is said to have been miraculously conceived by his mother, who, after a gestation of twelve years, gave birth to him at Chengji in Shensi. He taught his people to hunt, to fish, and to keep flocks. He showed them how to split the wood of the 桐 tóng tree, and then how to twist silk threads and stretch them across so as to form rude musical instruments.

From the markings on the back of a tortoise he is said to have constructed the EIGHT DIAGRAMS (q. v.), or series of lines from which was developed a whole system of philosophy, embodied later on in the mysterious work known as the Canon of Changes. He also invented some kind of calendar, placed the marriage contract upon a proper basis, and is even said to have taught mankind to cook their food.”120