Scroll

(幅)

The Chinese are past masters in the art of making scroll pictures and mottoes, a common form of ornamentation in every house throughout the country. Antithetical couplets, the wording of which is balanced with great precision, are written on red paper, and pasted on house-doors, in the belief that the revered character of holy and mystic origin will ensure continual happiness and prosperity to the household.

In Buddhism the scroll is the sacred text of the scriptures, and the store of truth. It is also the emblem of Hán Shān (寒山) a Chinese poet of the 7th century, and implies the unwritten book of nature. In former times books were made in rolls (vide WRITTEN CHARACTERS).

Seals

(圖章)

“Seals, among the Chinese, are made in many shapes, though the importance attached to them as attesting the validity of documents is hardly so great as it is among the Arabs and Persians. Motto seals are not uncommon, the characters of which are written in some one of the ancient forms, usually the zhuànzì (蒙字)—from this use called the seal character—and are generally illegible to common readers, and even to educated men, if they have not studied the characters. Seals containing names are more frequently cut in the common character, and ordinarily upon stone.”233 Wood, bone, ivory, crystal, china, glass, brass, and other substances are also employed, and the stamping-pad is generally composed of moxa punk or cotton wool mixed with bean oil and vermilion.

The examples illustrated will serve to exemplify the usual styles of cutting, and the sentiments commonly admired. The first three allude in their shape to the sentiments engraved thereon. The cash (the symbol of wealth) intimates that its possession is as good as all knowledge; the wine-cup refers to the pleasures of the wine bibber; and the new moon to the commencement of an affair, or the crescent-like eyebrows of a fine lady. The fourth is written in an ancient and irregular form cut in the style known as yïnzì (陰字), or female character, the fifth in a very square and linear form of the seal character cut in the style known as yángzì (陽字), and refers to the cosmogony of the Chinese, which teaches that heaven and earth produced man, who is between them, and should therefore be humble. In the sixth the characters with lines beneath are to be repeated, in order to complete the sentence. The characters of both the sixth and the seventh are zhuànzì of different ages; the latter approaches the original ideographic forms. In the eighth, which reads: “the sun among the clouds” (曰雲中), the middle character is a very contracted, running hand, while the other two are ancient forms.

Every Chinese official of any standing has had a seal of office since the establishment of the Sòng Dynasty, A.D. 960. The seals of the highest provincial officials were oblong and made of silver. Magistrates used square silver seals, and the lower official employed wooden seals. An official generally places his seal in the charge of his wife, as very serious consquences, entailing even dismissal from office, might result from its accidental loss. As the official seal denotes the power of authority, it has also come to be considered by the people as possessing potency for the cure of diseases, and impressions of such seals are sometimes torn from proclamations and other documents, and applied to sore places, ulcers, etc.

Secret Societies

(私會)

The numerous secret societies which have existed in China at various times have been formed chiefly for political, but sometimes also for religious, or personal reasons.

The chief of these organisations was the Triad Society (三合會), besides which may be mentioned the Vegetarians (喫素教), Elder Brothers (哥老會), Red Eyebrows (赤眉), Golden Orchid Sect (金蘭會), and the Boxers (義和拳).

The Triad Society was originally formed for the purpose of overthrowing the Manchus and restoring the Ming or Tartar Dynasty. In its complicated ceremonies of initiation many Buddhist and Taoist emblems are employed (vide Stanton: The Triad Society or Heaven and Earth Association, pp. 38 seq.).

The members of the Vegetarian Sect abstain from meat and put their hope in the Pure Land of the West (vide SHÂKYAMUNI BUDDHA).

The Elder Brothers base their society on the friendship of Liú Bèi (劉備), Zhāng Fēi (張飛), and Guān Yû (關羽), the three sworn brothers and heroes of the period of the Three Kingdoms.

The Red Eyebrows existed about the beginning of the Christian era and were originally a body of rebels who painted their eyebrows red.

The Emperor Asoka placed a great monolith called “The Pillar of Asoka” on the exact spot where the Gâutama Buddha was born, with the inscription “Here the Blessed One was born” and in 1895, Dr Führer—a noted archaeologist—discovered the pillar, when, by permission of the Maharajah of Nepaul, he was allowed to visit there.

The Golden Orchid Society is an association of girls sworn never to marry.

The Boxers were originally a society of women and youths who practised incantations and hypnotism and subsequently developed into an anti-foreign organisation.

There is said to be a considerable resemblance to Freemasonry in the ritual of many of the Chinese secret societies, which have always been under the ban of the law on account of their political or otherwise objectionable tendencies.

Seven Appearances

(七相)

The various emblematic and auspicious signs on the FOOTPRINTS OF BUDDHA (q. v.). They are the SWASTIKA, FISH, DIAMOND MACE, CONCH-SHELL, FLOWER-VASE, WHEEL OF THE LAW, and CROWN OF BRAHMA (q. q. v.).

Shâkyamuni Buddha

(釋迎牟尼)

“From Shâkya (one who is) mighty in charity, and muni (one who dwells in) seclusion and silence. The favourite name among the Chinese for the great founder of Buddhism.”234

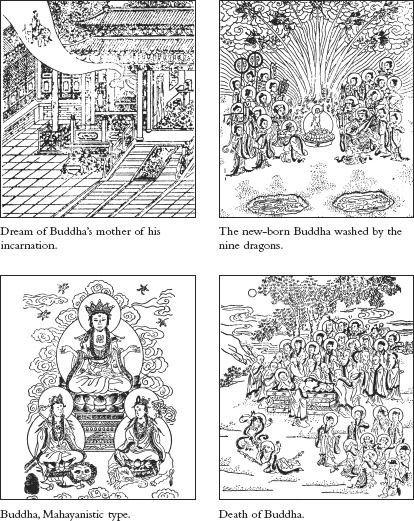

“Prince Siddartha, known as Shâkyamuni Gâutama Buddha, was born 624 B.C. at Kapilavastu (迴維羅衛)—‘the city of beautiful virtue’—on the borders of Nepaul (lat. 26° 46’N. and long. 83° 19’E), and died in his 80th year. He was the son of a king; but renounced the pomps and vanities of this wicked world to devote himself to the great task of overthrowing Brahmanism, the religion of caste.”235 His birthday is celebrated as a religious festival in China on the 8th day of the 4th moon. The traditional father of Buddha was the Brahman King Suddhodana (白淨王). His mother Maya (摩耶), or Maha-maya déva, was a daughter of Anjana or Anusâkya, King of the country of Koli, and Yasodharâ, an aunt of Suddhodana. There seem to have been various intermarriages between the royal houses of Kapila and Koli. At the age of fifteen the young Prince was made heir-apparent; at seventeen he was married to Yashodara, a Brahmin maiden of the Shakya clan, and his son Rahula was born in the following year.

According to the Lalita-Vistara, Shâkyamuni had “a large skull, broad forehead, and dark eyes; his forty teeth were equal and beautifully white, his skin fine and of the colour of gold; his limbs were like those of Ainaya, the king of the gazelles; his head was well shaped; his hair black and curly.” “The type of head conforms to fixed tradition regarding marks of identity (lakshanas)— e. g., eyebrows joined together; a bump of wisdom on the top of the head (ushnisha), covered in the case of the Bodhisattva by the high-peaked tiara; three lucky lines on the neck; the lobes of the ears split and elongated in a fashion still prevalent in Southern India; a mark in the centre of the forehead (urnã) symbolising the third eye of spiritual wisdom.”236 Representations of Buddha, though possessing these marks of identity, vary slightly according to the country in which they have been made, and show unmistakeable signs of national character. The deity is in fact an ideal racial type rather than an individuality.

There are numerous legendary incidents connected with the Buddha who gave up kingdom, city, wife, and son to devote himself to the inculcation of his doctrines. He is said, on one occasion, to have plucked out his eyes to give to another; he cut off a piece of his flesh to ransom the life of a dove pursued by a hawk; he gave his body to feed a starving tigress; he flung an elephant over a wall, etc. (vide Spence Hardy: Manual of Buddhism). He appeared six times in the form of an elephant; ten times as a deer; and four times as a horse (vide also BODHI TREE, ELEPHANT, FOOTPRINTS OF BUDDHA).

The relics of his body after his death and cremation at Kusinara (180 miles N. W. from Patna, near Kusiah, about 120 miles N. N. R. of Benares, and 80 miles due east of Kapilavastu) were divided among the eight kings of Kusinara, Pâvâ, Vaisîlî, and other kingdoms, who erected topes, pagodas, stupas, and temples in which they were enshrined; many of the relics subsequently passed into China and Japan, and great virtue was ascribed to them.

“The Chinese language, although extremely rich in symbols to convey all sorts of ideas, did not contain a character or symbol that would convey their highest ideals of the Founder of the Higher Buddhism— the Mahayana. They therefore invented one composed of two symbols, 弗 not, and  which means man. They wrote the symbol for their ideal Founder thus 佛, pronounced fó, meaning that he is not human but Divine.”237

which means man. They wrote the symbol for their ideal Founder thus 佛, pronounced fó, meaning that he is not human but Divine.”237

Buddha is generally represented as enthroned on the Lotus, the three right hand fingers being lifted in blessing; “the head is ‘snail-crowned,’

i. e., with the characteristic spiral curls, an allusion to the beautiful legend current in India that one day when, lost in thought as to how to assuage the world’s woes, Buddha was oblivious of the Sun’s fierce rays beating on his head, the snails in gratitude to Him who loved and shed his blood for all living things, crept up and formed a helmet of their own cool bodies.”238 He is sometimes figured holding a weaver’s shuttle in his hand, symbolical of his passing backwards and forwards from life to life, as the shuttle is guided by the weaver’s hand. He is also sometimes shown in feminine form as the Goddess of Fertility, holding a pot of earth in his left hand, and a germinating grain of rice in the left. He is occasionally depicted with the symbols of learning (book) and courage (spear-head) emanating from his closed fists. On the temple altars the golden Buddha is seated in the centre; on his right is usually Ânanda, the writer of the sacred books of the religion, and on his left Kas’yapa, the keeper of its esoteric traditions. But sometimes the place of these two disciples is occupied by two other representations of Buddha, viz., Buddha Past and Buddha Future.

Shâkyamuni Buddha was not the only Buddha or enlightened one; other Buddhas, some of whom may have been adopted from the legends or beliefs of the many races with which the faith had come in contact outside India, also receive the prayers of the devout, for example, AMITÂBHA, MAITREYA BUDDHA (q. q. v.), etc. Every intelligent being who has thrown off the bondage of sense, perception, and self, and knows the utter unreality of all phenomena, is qualified to become a Buddha. Râhula (羅喉羅), the eldest son of Shâkyamuni, is to be reborn as the eldest son of every future Buddha.

Buddhism was introduced into China in A.D. 67. The fundamentals and basis of the religion may be summed up briefly as follows:

1. Misery invariably accompanies existence.

2. Every type of existence, whether of man or of animals, results from passion or desire.

3. There is no freedom from existence but by the annihilation of desire.

4. Desire may be destroyed by following the eight paths to Nirvâna.

5. The “eight paths” are attained by correctness in one’s views, feelings, words, behaviour, exertions, obedience, memory, and meditations.

The Buddhist scriptures are chiefly written in Sanskrit or Pâli, but printed explanations in colloquial Chinese are also obtainable. The Three-fold Canon (三藏), Sanskrit: Tripitaka, or “three baskets,” consists of the Sûtras (修多羅) or doctrinal records, the Vinaya (比尼), or writings on discipline, and the Abhidharma (阿比暴), or writings on metaphysics.

The Five Precepts of Buddhism, Sanskrit: Pancha Veramani (五戒) are:

1. Slay not that which hath life (不殺生).

2. Steal not (不 盜).

盜).

3. Be not lustful (不欲邪行).

4. Be not light in conversation (不妄欲).

5. Drink not wine (不飮諸酒).

“Buddhism not only introduced a whole world of alien mythology, which for centuries provided a favourite theme for Chinese painters, sculptors, and designers in every branch of Art, but it also directed the very expression of these new ideas along the lines of Western tradition. To the present day Graeco-Indian and Persian elements are found mingled with the purely native decoration.”239

There are many Buddhist monasteries in China, and also numerous nunneries, the latter being more common in the South. The monastery consists of a number of buildings and courtyards facing south with living-rooms, etc., on each side. There is something truly majestic in the appearance of the broad and massive temples, with the grand upward sweep of their heavily-tiled roofs and deep-shaded eaves, with an intricate maze of supports and carvings beneath; the whole sustained on colossal round posts locked and tied together by equally massive timbers (vide ARCHITECTURE). The first temple is called the Hall of the Four Great Kings (vide FOUR HEAVENLY KINGS), containing the images of those worthies, and also of MAITREYA BUDDHA, WEI T‘O and GOD OF WAR (q. q. v.). The second is the Precious Hall of the Great Hero (大雄寶殿) containing figures of SHÂKYAMUNI BUDDHA, sometimes accompanied by AMITABHA and MANJUSRI (q. q. v.) or some other. KUAN YIN (q. v.) has a shrine at the back of the altar facing north, and DI ZANG (q. v.) is also accommodated, while the EIGHTEEN LOHAN (q. v.) are seated along the sides. The third temple is the Fâ Táng (法堂), and is used for religious services.

The number of monks (和 ) in a monastery varies from 30 to 300 according to the size of the establishment. There are three ceremonies of initiation, the first being the admission as novice, the second the reception of the robes and bowl and pledge of obedience to the rules of the Pratimokoksha, and the third is the acceptance of the Bodhisattva’s commandments (受菩薩戒), or the 58 precepts of Brahma’s Classic (梵王經), when the candidate’s head is branded by lighting pieces of charcoal placed on the shaven pate.

) in a monastery varies from 30 to 300 according to the size of the establishment. There are three ceremonies of initiation, the first being the admission as novice, the second the reception of the robes and bowl and pledge of obedience to the rules of the Pratimokoksha, and the third is the acceptance of the Bodhisattva’s commandments (受菩薩戒), or the 58 precepts of Brahma’s Classic (梵王經), when the candidate’s head is branded by lighting pieces of charcoal placed on the shaven pate.

The primitive form of Buddhist doctrine is known as Hînayâna or xiâochéng (小乘), lit : “Small Coveyance,” also styled Theravada, or “School of Elders.” It is characterised by the presence of much moral asceticism and the absence of speculative mysticism. It was succeeded by an advanced phase of dogma called Mahâyâna, or dàchéng (大乘),“Great Vehicle,” with a less important link, Madhymâyanâ. While both sects claimed their doctrines to be the “vehicles” or means of arriving at Nirvâna (淫樂) or Salvation, the Mahâyânist creed is more emotional, ornate, and fanciful than the practical asceticism of the Hinayâna, and it advocates the power of human beings to actually become Bodhisattvas or divine beings by faith in Buddha. The two schools are sometimes spoken of as the Northern and Southern Buddhism.

With the introduction of the Mahâyâna system, the mysterious Nirvâna had, as a reward for virtue, been supplemented by a “Pure Land in the West” (西方淨土), Sanskrit, Sukhavati, where there is fullness of life, and no pain nor sorrow, no need to be born again, no Nirvâna even. This happy land is surrounded with a sevenfold row of railings, a sevenfold row of silk nets, and a sevenfold row of trees. “In the midst of it there are seven precious ponds, the water of which possesses all the eight qualities which the best water can have, viz., it is still, it is pure and cold, it is sweet and agreeable, it is light and soft, it is fresh and rich, it tranquilises, it removes hunger and thirst, and finally it nourishes all roots. The bottom of these ponds is covered with golden sands, and round about there are pavements constructed of precious stones and metals, and many two-storied pavilions built of richly-coloured transparent jewels. On the surface of the water there are beautiful lotus-flowers floating, each as large as a carriage-wheel, displaying the most dazzling colours, and dispersing the most fragrant aroma. There are also beautiful birds there, which make delicious, enchanting music, and at every breath of wind the very trees on which those birds are resting join in the chorus, shaking their leaves in trembling accords of sweetest harmony.”240 This abode of bliss was naturally more attractive than the abstract and uninteresting Nirvâna of the Hînayânists, which is described as “the state of a blown-out flame.”

It is a well-known fact that the principal religions of the world have borrowed largely from primitive beliefs and observances for the formulation of their ritual worship. Buddhism has much in common with Roman Catholic Christianity, having its purgatory, its Goddess of Mercy, and its elaborate machinery for delivering the dead from pain and misery through the good offices of the priests. Among other similarities may be mentioned celibacy, fasting, use of candles and flowers on the altar, incense, holy water, rosaries, priestly garments, worship of relics, canonization of saints, use of a dead language for the liturgy and ceremonials generally. The trinity of Buddhas, past, present, and future, is compared by some to the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. The immaculate mother of Shâkyamuni, whose name Maya is strikingly similar to that of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is also to be noticed, while Buddha’s temptation on Vulture Peak by Mara the Evil One, may also be contrasted with the similar temptation of our Lord. The eighteen Lohan (formerly less in number), or followers of Buddha, have also been compared with the twelve disciples of Christ, who was born 600 years later than Buddha. The worship of ancestors is in some measure akin to the saying of masses for the dead, and at one time the Jesuits considered it a harmless observance and tolerated it in their converts. Finally the Dalai Lama is a spiritual sovereign closely resembling the Pope.

Sheep

(羊)

The written symbol representing the sheep is a conventional picture, or birds’-eye view, of a ram, showing horns, feet, and tail.

The sheep or goat (called the hill-sheep) is the eighth symbolic animal of the TWELVE TERRESTRIAL BRANCHES (q. v.), and the emblem of a retired life. The lamb is the symbol of filial piety, as it is said to kneel respectfully when taking its mother’s milk. The goat is one of the six sacrificial animals and was undoubtedly known in China long before the sheep, which was a later importation called the “Hun-goat” (胡半). According to an ancient legend, five venerable magicians, clothed in garments of five different colours, and riding on rams of five colours, met at Canton; each of the rams bore in his mouth a stalk of grain having six ears, and presented them to the people of the district, to whom the magicians said: “May famine and dearth never visit your markets.” Having said these words they immediately disappeared, and the rams were changed into stone. Canton has therefore come to be known from this legend as the City of Rams (羊城).

The domestic sheep (綿羊) is the broad-tailed species, and is not so common as the goat (山羊) in the northern provinces. The long wool is shorn in some parts of China. The animals are chiefly fed on cut fodder owing to the scarcity of good grazing. The mutton is of good quality, and is consumed by Mohammedans, being only occasionally introduced at Chinese tables. The wild sheep (盤羊) has a ram’s head with long spiral horns, and a deer-like body. There are various species, e. g., Ovis argale, ranging over the Altai and Daurian Mountains; O. jubata, found in Mongolia, Shansi, and Hopeh; and O. nahura, a small animal which occurs in Kansu.

Shop-signs

(幌 )

)

The variety and effectiveness of Chinese sign-boards is well known, but the symbols and emblems which accompany them are also worthy of attention. Shop-signs are usually images or pictures of the articles sold and generally have a red pennon attached to them. They are of all shapes and sizes, fixed in stone sockets on the ground, hanging from the eaves of the roofs, painted on the walls, lintels and door-posts, or suspended from a pole protruding over the street. The sign-board sometimes sets forth the name and birth-place of the proprietor as well as his trade or profession.“The sign-boards are often board planks fixed in stone bases on each side of the shop-front and reaching to the eaves, or above them; the characters are large and of different colours, and in order to attract more notice, the signs are often hung with various coloured flags bearing inscriptions setting forth the excellence of the goods.”241 “Some of them are ten or fifteen feet high, and being gaily painted and gilded on both sides with picturesque characters, a succession of them seen down a street produces a gay effect. The inscriptions merely mention the kind of goods sold, and without half the puffing seen in Western cities.”242

The practice of persons keeping small tables, where money can be changed, is very common in China. “Those who are itinerant, usually provide themselves with a small table, about three feet long by fifteen inches wide, and establish it on the way-side, at the corners of the streets, before the temples, and in the markets; in short, wherever there is a thoroughfare, the money-changer is not far off. The strings of copper cash are piled on one side, often secured to the table by a chain, and the silver is kept in drawers, with the small ivory yard with which it is weighed, which is more peculiarly the implement of this profession. Their sign is a wooden figure carved in the form of a cylinder to represent a string of cash.”243

Shùn

(舜)

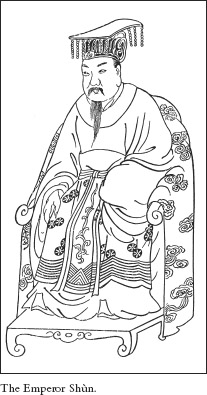

2317–2208 B.C. A native of Yú Mù (虞幕) in Honan. His father Gû Sôu (誓瞪), said to be a descendant of the Emperor Zhuān Xü (顕頑), having a favourite son by a second marriage, took a dislike to Shùn, and, assisted by his wife, made several attempts to kill him.

By his exemplary conduct towards his parents in spite of their ill-feeling, Shùn has since been included in the twenty-four historic examples of filial piety.

At the age of twenty he attracted the notice of the Emperor YAO (q. v.), who made him his heir, setting aside his own unworthy son, and giving Shùn his own two daughters Nǚ Yïng (女英) and É Huáng (娥皇) in marriage.

He was gifted with extraordinary mental and physical qualities, and was said to have had double pupils in his eyes, which no doubt added to his quick perception and ready grasp of the principles of good government. He received the title of Chóng Huā (重華), implying that he rivalled his predecessor Yáo in virtue. At his death he was canonised as Yú Dìshùn (虞帝舜).

Silk

(絲)

The written symbol in use to express the word “silk”—derived from the Chinese sï through the Latin sericum —is composed of the form sï (糸) in duplicate, consisting of sï (ム) repeated, derived from the figure of a silkworm coiled up in its cocoon, with three twisted filaments issuing thereform.

The silkworm is an emblem of industry and its product is symbolic of delicate purity and virtue. The art of sericulture originated in China, and Léi Zû (螺祖), or the Lady of Xïlíng (西陵氏), Consort of the Yellow Emperor, 2698 B.C., is said to have introduced the rearing of silkworms and the use of the loom.

“The name China is derived from sï which is the Chinese word for silk. All the names by which China was known to the ancients were also derived from that of the precious fibre. Seres, Tsin, Sinem, Sereca, and others all signify the land of silk. China is said to have an uninterrupted literary history which goes back to between two and three thousand years B.C., and in it there are many references to the silkworm, sericulture, silk weaving, and silk embroidery.”244

During the reign of the Yellow Emperor the annual festivals of agriculture and sericulture were first instituted. In these festivals, among other ceremonies, the reigning emperor ploughed a furrow, and the empress made an offering, at the altar of her deified predecessor, of cocoons and mulberry leaves.

Chinese designs on silk are characterized by a natural treatment of flowers and other objects, and also of many frequently-repeated symbolic forms.

“The sericultural industry is pursued universally among the Chinese, but with the exception of main silk centres, the work is not attended to with any considerable zeal. Again, outside of Kwangtung and Kwangsi, the industry is pursued as a side business of farmers, and consequently run on a small scale.”245

White silk is spun by the cultivated caterpillar Bombyx mori, which feeds on mulberry-leaves, wild silk of a brownish colour is reeled from the cocoons of the Tussah or Antheraea mylitta, which feeds on Manchurian oak-leaves, and a yellow variety is produced in Szechuan. The mulberry trees are planted round the edges of fields devoted to grain and other crops, or are grown on the raised embankments which separate the paddy-fields. Heavy damage is inflicted upon the silkworms by the Merococcus, causing a disease which develops in the worms just before they begin to cocoon. If diseased worms were discarded, and the eggs scientifically developed, a larger yield of better quality silk would undoubtedly result. The Yangtze valley is certainly capable of five times its present production. The International Sericultural Association, however, renders valuable assistance by the distribution of healthy selected stock-worms. Dr. Vartan Osiglan’s super-size worm, which—according to the Illustrated Review, Atascadero, California, January, 1921—spins a cocoon containing 1,800 yards of silk in any of eighteen different natural colours graduated by its diet, might with some advantage be introduced into China.

Silk is the premier article among the exports of the country. With the adoption of modern methods and steam filatures in all the leading centres, the quantity and quality of this important product would be very greatly improved.

“China was, no doubt, the first country to ornament its silken web with a pattern; the figured Chinese silks brought to Constantinople were there named ‘diapers,’ but after the 12th century, when Damascus became celebrated for its looms, the name of damask was applied to all silken fabrics richly wrought and curiously designed, and Chinese figured silks were included under this class. The designs used in weaving and embroidery are of varied character and can be traced back to very ancient times—the silk weaver is the most conservative of artisans and continues to use all the old patterns.”246

Silver

(銀)

The written symbol for this metal, which is an emblem of brightness and purity, is described as consisting of the form gên (良), obstinate, and jïn (金), metal, because it is so difficult to find in China. Argentiferous galena occurs, however, to some extent in Yunnan, Kuangsi, Kueichow, and Szechuan. Importations are made from India.

The use of silver as a measure of value became common under the Míng Dynasty in the form of shoe-shaped ingots (元寶) or xìsï (細絲). Dollars and subsidiary coinage are produced in the various mints. Before a silver ingot has solidified in the mould it is lightly tapped, when fine silk-like lines appear on the surface of the metal. The higher the “touch” (色) or purity of the xìsï, the more like fine silk are the markings on its surface. Those ingots may be of any weight from 1 to 100 ounces.

A silver locket is sometimes suspended from a child’s neck to protect it from evil influences. The milky way is poetically styled the “silver river” (銀河), the moon, the “silver sickle” (銀釣), or “silver candle” (銀燭), and the human eye, the “silver sea” (銀海).

Skeleton Staff

(骸骨棒)

A staff of wood or bone in the form of a conventional skeleton, and used by the Lama priests in their devil worshipping ceremonies (vide Illustration under LAMAISM).

Skull-cup

(顧杯)

A libation cup fashioned from a human skull, Sanskrit, Kapãla. Used in Lamaism on the altars of the fiercer deities. It is usually mounted on a brass stand and filled with samshu, or rice-spirit (vide Illustration under LAMAISM).

Snake

(蛇)

The written symbol representing the snake is compounded of the form chóng (虫), reptile or worm, and tuó (它), hump-backed, which is derived from the figure of a cobra rising on its tail with dilated neck and darting tongue.

The serpent is one of the symbolic creatures corresponding to the sixth of the TWELVE TERRESTRIAL BRANCHES (q. v.), and is the emblem of sycophancy, cunning, and evil, while at the same time it is regarded with feelings of awe and veneration owing to its supposed supernatural powers and its kinship with the benevolent dragon. It is said to be very unlucky to injure a snake which has made its domicile below the floor of one’s house; while to purchase a snake that has been captured, and liberate it, is considered a good deed that will not go unrewarded. The Chinese believe that elfs, demons, and fairies often transform themselves into snakes. The Buddhist priests occasionally harbour snakes around their temples.

According to one of the fables in the Shān Hâi Jïng (山海經), there was once a snake in Szechuan which devoured elephants and took three years to disgorge their bones. Pythons measuring upwards of 20 feet in length are, however, found in the far south of China. The most common snake is the harmless Columbrine, which is chiefly found under the floors of Chinese houses. Dilapidated graves afford seclusion for many of these reptiles. There are not many poisonous varieties, though the cobra is occasionally seen in the south, and certain species of vipers occur in various parts. Snakes are offered for sale as food in many cities and the poisonous kinds are sold to the druggists for the manufacture of medicines. The Chinese have various herbal remedies for snake-bite, and the mashed head of the reptile is sometimes applied to the wound as a poultice, on the principle of “the hair of the dog.”

Snare

( )

)

Sanskrit Pãsa. A symbol of Siva, Varuna, and Lakshmi, employed in Lamaism. Its purpose is to rescue the lost or bind the opponents. It consists of a cord or chain with knots or metal knobs at each end (vide Illustration under LAMAISM).

Spear

(矛)

Many different varieties of long pointed weapons were employed by the Chinese until comparatively recent times in warfare and hunting. The long spear, curved lance, tiger-head hook, moon-shaped sickle, javelin, long shuttle, toothed spike, and halberd were commonly used in ancient times.

A spear or lance is one of the weapons or insignia of some of the Buddhist and Taoist divinities. It sometimes has a red pennon or tassel attached to it near the point (vide TRIDENT).

Spiritualism

(招魂術)

Communication with the souls of the departed has been practised by the Chinese from remote ages, both by means of automatic writing and with the aid of a psychic medium. The methods adopted are similar in many cases to those employed in other countries, and the science is, as in the western world, generally connected with religious observances. Spiritualistic seances, during which darkness seems to be indispensable, are frequently held in temples under the auspices of the priests, who are often gifted with pronounced psychic powers. Women, owing to their temperamental and emotional nature, are also often found to possess skill in this respect, and there are certain varieties of spiritualistic medium known as mâjiâo (馬 ), guòyïn (過陰), línggü (靈姑), etc., who work themselves into frenzies or fall into trances, under the influence of which they profess to be able to communicate with the spirit world.

), guòyïn (過陰), línggü (靈姑), etc., who work themselves into frenzies or fall into trances, under the influence of which they profess to be able to communicate with the spirit world.

It is only natural that, since ANCESTRAL WORSHIP (q. v.) is so firmly established in China, there should be a strong desire on the part of the living to profit by the counsels of the dead. Divination has been practised for centuries by means of the system known as fúluàn (扶乱) or planchette, when a forked stick, with a projecting style or point, is grasped by two men standing back to back, and characters are traced legibly on a table covered with sand, placed before the shrine of a god, forming an appropriate response to any question that may have been put to the oracle. A brush pen suspended by a hair, and resting on a piece of paper, is also employed for the same purpose.

A number of inscribed bones unearthed in Honan are said to have been used for purposes of divination (vide illustration under WRITTEN CHARACTERS). In ancient times the shell of the tortoise was heated and the future divined from the fissures thus created (占卜), while fortune-telling by the casting of lots (抽籠), and the working out of horoscopes (算卦) is common at the present day.

“The belief in spirits and in a future state generally has prevailed in China from the earliest ages, though not in any way recognised by Confucianism which preserves an agnostic attitude towards all spiritual questions. A heaven and a hell were introduced by the Buddhists, and borrowed by the Taoists as a defensive measure against their more attractive rival. The popular belief now is that there is a world of shades, an exact model of the present life, with penalties and rewards for wicked and deserving persons.”247 An exhaustive account of Chinese demonalatry is given in de Groot’s Religious System of China. For descriptions of Heaven and Hell (vide LAOCIUS, SHÂKYAMUNI BUDDHA, and YAMA).

There is a Chinese theory that the animus (魂) can issue from the body during the state of trance or coma, leaving the body sustained by the anima (魄). Clairvoyantism (神視力), mesmerism (符), and palm-istry (相手法) are commonly practised to discover that which is beyond the reach of human ken. Auto-hypnosis (工夫), or a system of exercises for the production in oneself of abnormal psychic conditions (ecstacy, etc.), is practised by the Taoists. The original organisation of the Boxers employed hypnotic methods to produce enthusiasm and insensibility to pain.“We read how the Emperor Wû Dì of the 2nd century B.C., when he lost a favourite concubine whose beauty was such that ‘one glance would overthrow a city, two glances a State,’ engaged a magician to put him in communication with her departed spirit.”248

Spleen

(脾)

The spleen is regarded by the Chinese as one of the emotional centres of the body, and a man’s disposition is said to be regulated by it. It is reverenced as one of the EIGHT TREASURES (q. v.) or Eight Precious Organs of Buddha, and is sometimes called sân (傘), when it symbolises the sacred UMBRELLA (q. v.) of the Buddhists.

This organ is said to correspond to the element earth, and with the stomach has the office of storing up; the five tastes emanate from the spleen and the stomach.

Stars

(星)

The Chinese records show remarkable acquaintances with stars, and many curious theories are based thereon. That the mysteries of human life, the differences between people and their fates should be connected with the equally inexplicable but regular movements of the beautiful orbs in the sky, cannot be wondered at.

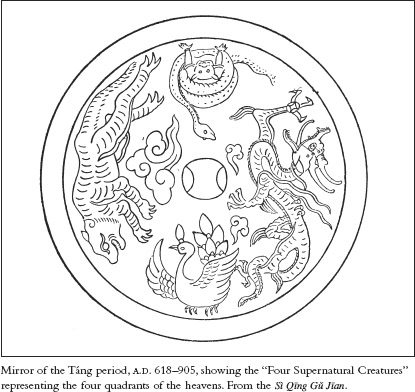

“The division of the celestial sphere into twenty-eight constellations was conceived more than 3,000 years ago, for it is mentioned in the Chou Ritual. The character 括 used for these constellations is taken to mean the ‘mansions’ or ‘resting-places’ of the sun and moon in their revolutions. Seven of these stellar ‘mansions’ were allotted to each of the four quadrants of the vault of heaven. The quadrants were associated with four animals, often called the ‘Four Supernatural Creatures’ (四神), which maintain their importance and exert an influence over national life to the present day, especially in the domain of geomancy.... The ‘Azure Dragon’ (青龍) presides over the eastern quarter, the ‘Vermilion Bird’ (朱鳥)— i. e. the Chinese phoenix—over the southern, the ‘White Tiger’ (白虎) over the western, and the ‘Black Warrior’ (玄武)— i. e. the tortoise—over the northern. From an analogy between a day and year, it can be understood how these animals further symbolised the four seasons. The morning sun is in the east, which hence corresponds to Spring; at noon it is south, which suggests Summer. By similar parallelism the west corresponds to Autumn, and the north to Winter.”249

The stars are grouped under the twenty-eight constellations or asterisms, also know as gōng (宮), as follows:

1. 角. Jiâo, the Horn, consisting of four stars, in the form of a cross, viz., Spica, Zeta, Theta, and Iota, about the skirts of Virgo. Represented by the Earth Dragon. Element, Wood.

2. 冗. Kàng, the Neck, four stars in the shape of a bent bow, viz., Iota, Kappa, Lambda, and Rho in the feet of Virgo. Represented by the Sky Dragon. Element, Metal.

3. 氏. Dî, the Bottom, four stars in the shape of a measure, viz., Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Iota, in the bottom of Libra. Represented by the Badger. Element Earth.

4. 房. Fáng, the Room, four stars nearly in a straight line, viz., Beta, Delta, Pi, and Nun, in the head of Scorpio. Represented by the Hare. Element, Sun.

5. 心. Xïn, the Heart, three stars, viz., Antares, Sigma, and Tau, in the heart of Scorpio. Represented by the Fox. Element, Moon.

6. 尾. Wêi, the Tail, nine stars in the shape of a hook, viz., Epsilon, Mim, Zeta, Theta, Iota, Kappa, Lambda, and Nun, in the tail of Scorpio. Represented by the Tiger. Element, Fire.

7. 算. Jï, the Sieve, four stars in the form of a sieve, viz., Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, and Beta, in the hand of Sagittarius. Represented by the Leopard. Element, Water.

8. 斗. Dôu, the Measure, six stars in the shape of a ladle, viz., Mim, Lambda, Rho, Sigma, Tau, and Zeta, in the shoulder and bow of Sagittarius. Represented by the Griffon. Element, Wood.

9. 牛. Niú, the ox, six stars, viz., Alpha, Beta, and Pi, in the head of Aries, and Omega, with A and B in the hinder part of Sagittarius. Represented by the Ox. Element, Metal.

10. 女. Nǚ, the Girl, four stars in the shape of a sieve, viz., Epsilon, Mim, Nin and 9, in the left hand of Aquarius. Represented by the Bat. Element, Earth.

11.  . Xü, Emptiness, two stars in a straight line, viz., Beta in the left shoulder of Aquarius, and Alpha in the forehead of Equleus. Represented by the Rat. Element Sun.

. Xü, Emptiness, two stars in a straight line, viz., Beta in the left shoulder of Aquarius, and Alpha in the forehead of Equleus. Represented by the Rat. Element Sun.

12. 危. Wēi, Danger, three stars in the shape of an obtuse-angled triangle, viz., Alpha in the right shoulder of Aquarius and Epsilon or Enif, and Theta in the head of Pegasus. Represented by the Swallow. Element Moon.

13. 室. Shì, the House, two stars in a straight line, viz., Alpha or Markab, in the head of the wing, and Beta or Sheat, in the leg of Pegasus. Represented by the Bear. Element, Fire.

14. 璧. Bì, the Wall, two stars in a straight line, viz., Gamma, or Algenib, in the tip of the wing of Pegasus, and Alpha in the head of Andromeda. Represented by the Porcupine. Element, Water.

15.  . Kuí, Astride, sixteen stars, said to be like a person striding, viz., Beta, or Mirac, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Nim, Nun, Pi in Andromeda, two Sigmas, Tau, Nun, Pi, Chi, and Psi, in Pisces. Represented by the Wolf. Element, Wood.

. Kuí, Astride, sixteen stars, said to be like a person striding, viz., Beta, or Mirac, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Nim, Nun, Pi in Andromeda, two Sigmas, Tau, Nun, Pi, Chi, and Psi, in Pisces. Represented by the Wolf. Element, Wood.

16. 宴. Lóu, a Mound, three stars in the shape of an isosceles triangle, viz., Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, in the head of Aries. Represented by the Dog. Element, Metal.

17. 胃. Wèi, the Stomach, three principal stars in Musca Borealis. Represented by the Pheasant. Element, Earth.

18. 晶. Mâo, seven stars in Pleides. Represented by the Cock. Element, Sun.

19. 畢. Bì, the End, six stars in Hyades, with Nim and Nun of Taurus. Represented by the Raven. Element, Moon.

20. 背. Zï, to Bristle up, three stars, viz., Lambda and two Phi, in the head of Orion. Represented by the Monkey. Element, Fire.

21. 參. Shēn, to Mix seven stars, viz., Alpha, or Betelgeux, Beta or Rigel, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, and Kappa, in the shoulders, belt, and legs of Orion. Represented by the Ape. Element, Water.

22. 井. Jîng, the Well, eight stars, viz., four in the feet and four in the knees of Gemini. Represented by the Tapir. Element, Wood.

23. 鬼. Guî, the Imp, four stars, viz., Gamma, Delta, Eta, and Theta, in Cancer. Represented by the Sheep. Element, Metal.

24.  . Lîu, the Willow, eight stars, viz., Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Rho, Sigma, and Omega in Hydra. Represented by the Muntjak. Element, Earth.

. Lîu, the Willow, eight stars, viz., Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Rho, Sigma, and Omega in Hydra. Represented by the Muntjak. Element, Earth.

25. 星. Xïng, the Star, seven stars, viz., Alpha, Iota, two Taus, Kappa, and two Nuns, in the heart of Hydra. Represented by the Horse. Element, Sun.

26. 張. Zhāng, to Draw a Bow, five stars in the form of a drawn bow, viz., Kappa, Lambda, Mim, Nun, and Phi, in the second coil of Hydra. Represented by the Deer. Element, Moon.

27. 翼. Yì, the Wing, twenty-two stars in the shape of a wing, all in Crater and the third coil of Hydra. Represented by the Snake. Element, Fire.

28.  . Zhên, the Cross-bar of a carriage, four stars, viz., Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon, in Corvus. Represented by the Worm. Element, Water.

. Zhên, the Cross-bar of a carriage, four stars, viz., Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon, in Corvus. Represented by the Worm. Element, Water.

The above characters are applied in regular order to the days of the lunar month. Four of them, viz., 房 (No. 4),  (No. 11), 昂 (No. 18), and 星 (No. 25) always mark the Christian Sabbath, and are denoted by the character 密, the days of the sun or “the ruler of joyful events” traced to the Persian mitra, while the others designate the week days respectively. It may be noted that the Chinese term xïngqï (星期), or “star period,” is applied to a lucky day appointed for a wedding, and is also used in the sense of “week” or “Sunday.”The constellations are further divided into four quadrants (四宿) vide supra —of which the Azure Dragon comprises Nos. 1 to 7, the Black Warrior 8 to 14, the White Tiger 15 to 21, and the Vermilion Bird 22 to 28 (vide also Giles: Chinese English Dictionary, Pt. 1, pp. 26–7).

(No. 11), 昂 (No. 18), and 星 (No. 25) always mark the Christian Sabbath, and are denoted by the character 密, the days of the sun or “the ruler of joyful events” traced to the Persian mitra, while the others designate the week days respectively. It may be noted that the Chinese term xïngqï (星期), or “star period,” is applied to a lucky day appointed for a wedding, and is also used in the sense of “week” or “Sunday.”The constellations are further divided into four quadrants (四宿) vide supra —of which the Azure Dragon comprises Nos. 1 to 7, the Black Warrior 8 to 14, the White Tiger 15 to 21, and the Vermilion Bird 22 to 28 (vide also Giles: Chinese English Dictionary, Pt. 1, pp. 26–7).

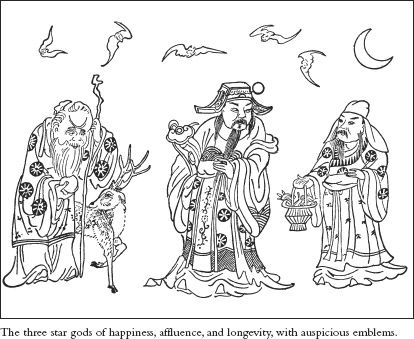

The Great Bear occupies a prominent position in the Taoist heavens as the aerial throne of their supreme deity, Shang Di, around whom all the other star-gods circulate in homage. The Northern Dipper (北斗), a group of stars in Ursa Major, is frequently worshipped by the Chinese on the fourteenth or fifteenth day of the eighth month, together with the Southern Dipper (南斗) in the southern heavens. They are also styled shòuxïng (壽星) and lǜxïng (祿星) respectively, and represent the Gods of Longevity and Wealth.

In this ceremony a rice measure (斗), half filled with rice and decorated on the exterior with stars, is placed in a perpendicular position, and at each of the four corners is placed some utensil, e. g., a pair of scales, a foot measure, a pair of shears, and a mirror, an oil lamp standing in the centre of the rice measure. The table also bears candles and sticks of incense. The object of the worship (拜斗) is to ensure longevity and affluence. The “Mother of the Measure” (斗拷), or the Queen of Heaven (天后), the Buddhist Goddess Martichi (摩禾支)—sometimes represented with eight arms, which are holding various weapons and religious insignia—who dwells among the stars that form the Dipper in the Constellation of the Great Bear, is also worshipped, chiefly by sailors (vide QUEEN OF HEAVEN). Taoist priests are called upon to officiate, which they do by ringing bells, reciting formulas, walking slowly round the table, and bowing towards it. Various dishes of food are also offered up on the table or altar. The Chinese say “rice is the staff of life, so the rice measure is the measure of life.”The Chinese word for “measure” has the same sound as a constellation, which probably accounts for the connection between the two.250

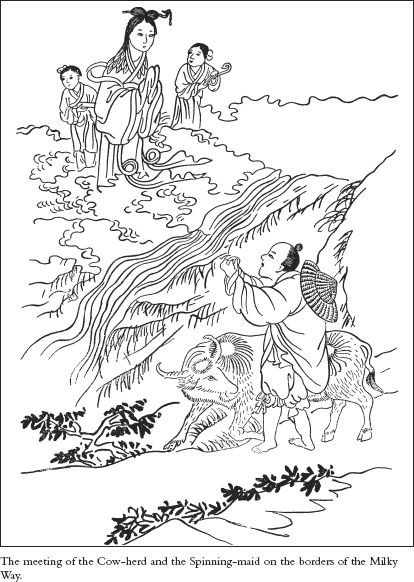

A remarkable legend is related by the philosopher Huái Nánzî (淮南子) in connection with the stars Vega in the constellation Lyra, and Altair in Aquila. In this story Qiān Niú (牽牛), the Cow-herd (Altair), has an affinity for Zhï Nǚ (織女), the Spinning-maid (Vega), and at one time when they were visiting the earth they were married. Afterwards they returned to heaven, but they were so happy with each other that they refused to work. The King and Queen of Heaven were angry at this, and decided to separate the two: so the Queen “with a single stroke of her great silver hair-pin, drew a line across the heavens, and from that time the Heavenly River has flowed between them, and they are destined to dwell forever on the two sides of the Milky Way. Their evident affection and unhappy condition moved the heart of His Majesty, and caused him to allow them to visit each other once each revolving year, on the seventh day of the seventh moon. But permission was not enough, for as they looked upon the foaming waters of the turbulent stream they could but weep for their wretched condition, for no bridge united its two banks, nor was it allowed that any structure be built which would mar the contour of the shining dome. In their helplessness the magpies came to their rescue. At early morn on the seventh day of the seventh moon, these beautiful birds gathered in great flocks about the home of the maiden, and hovering wing to wing above the river, made a bridge across which her dainty feet might carry her in safety. But when the time for separation came, the two wept bitterly, and their tears falling in copious showers are the cause of the heavy rains which fall at that season of the year.”251 It is said that there are no magpies to be seen on the seventh day of the seventh moon, as if any refuse to go to Heaven to help build the bridge they are afflicted with scabies. The two small stars close to Vega are twins, the children of the Spinning-maid and the Cow-herd, and from time immemorial it has been known that the Yellow River is a prolongation of the Milky Way, the waters of which are soiled by earthly contact and contamination. The Spinning-maid is revered as the patroness of embroidery and weaving.

A comet is a very unlucky omen; and the appearance of Halley’s comet in 1910–11 brought with it a great deal of unrest and fear. The people believe that it indicates calamity such as war, fire, and pestilence (vide also ASTROLOGY).

Stomach

(胃)

One of the Five Viscera (五藏), viz., heart, liver, stomach, lungs, and kidneys. The stomach is regarded by the Chinese as the seat of learning and repository of truth, and is reverenced as one of the EIGHT TREASURES (q. v.) or Eight Precious Organs of Buddha, and is sometimes called guàn (確), when it symbolises the sacred JAR (q. v.) of the Buddhists.

Stone

(石)

The written symbol for the word stone, which represents radical 112, comprises the character kôu ( ), depicting a fragment of rock detached or fallen from a cliff (厂). It is the emblem of reliability and hardness.

), depicting a fragment of rock detached or fallen from a cliff (厂). It is the emblem of reliability and hardness.

Stone abounds in southern and western China, and marble, granite, sandstone, and limestone are all used for building purposes in a rough as well as in a dressed state, while pulverized stone is used for making toothpowder and cosmetics. Stone monuments, archways, artificial rockwork, and architectural reliefs are sculptured with great skill by the Chinese, who thus display their artistic and symbolic designs with striking effect.“Ornamental walls are frequently formed of large slabs set in ports, like panels, the outer faces of which are beautifully carved with figures representing a landscape or a procession.”252 The stone-cutter produces large numbers of monuments and statues for public and private use, and for placing at the grave.

The carving and cutting of semi-precious stoneware is carried out with great accuracy and artistic finish. Jade, agate, cornelian, lapis-lazuli, malachite, coral, fluorspar, and crystal are cut into figures, while Shansi amethyst and turquoise matrix are made into beads and pendants. Juvenile workers are largely employed as apprentices, and can be seen at their rough lathes, hollowing out agates, etc., in preparation for the external working of the piece. Natural markings in the stone are invariably adapted for the cutting of leaves and floral sprays, etc., in order to enhance the beauty of the article, and no effort is spared in utilising the grain and markings to the best effect. A design may often take several months to work out satisfactorily. A rough-shaped stone might suggest, for example, a dragon, on account of its peculiar shape; it may have an awkward shaped top, which, however, must not be cut away or wasted; the part at the top may suggest a hill, so the dragon is carved coming round a hill, and any natural markings in the hill can be cut in relief as dwarf shrubs, rocks, or any other motifs which will appear to be suitable to the engraver. The designer’s motto might well be “Artistry, but Economy.”

The practice of burying figures of stones, clay, metal, etc., with the dead is of great antiquity. They were generally in the shape of servants, concubines, horses, etc., and were interred with the dead primarily for superstitious reasons relating to the invisible powers of evil and the means of controlling them, in fact with fetish worship, and secondarily in connection with the honours paid to deceased celebrities by the sacrifice of human beings and domestic animals to attend them in the land of shadows (vide DEATH). Stone statues (石象) of men and animals were erected before the tombs of Chinese Emperors and high officials for the same reasons as the figures were placed with the corpse; effigies made of coloured paper are now also burnt at the graveside. Sacrifices of animals at the grave have been carried out from time immemorial, but living sacrifices were not introduced until life-size images of human beings had first been erected before the grave and their miniature counterparts interred with the body. Some of the ancient stone figures and bas-reliefs found in China reveal traces of Indian or Grecian origin, while others are purely Chinese in conception. If extensive excavation was not impeded for reasons of FENG SHUI (q. v.), no doubt many interesting sculptures would be unearthed, which would be highly important from an archaeological standpoint (vide also JADE).

Mount Tài (泰山), in Shantung, has the epithet of “eminent” attached to it as it is the most famous of all the mountains of China. A stone from this sacred mountain is believed to have the power to ward off demons, though any local stone may be employed. The following inscription is cut upon it: “This stone from Mount Tài dares to oppose” (泰山石敢當), and it is sometimes erected at sharp turnings of the road where evil influences are considered likely to strike against it. No doubt the origin of the motto is partly due to the security offered by Mount Tài in times of flood and Yellow River disaster in Shantung, and to its former use in the worship of the sun.

Stone Chime

(磐)

The stone chime is a musical instrument of percussion, consisting of a plate in the form of an angle or T-square, made of jade or other stone and sometimes of bronze.

It is employed in the hymnal service in honour of Confucius, which takes place in Spring and Autumn. It is one of the EIGHT TREASURES (q. v.), and is sometimes carved on the ends of rafters, etc., when it represents the word of the same sound, qìng (慶), meaning felicity (vide MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS).

Sü Shì

(蘇車式)

Commonly known as Sü Dōngpō (蘇東坡). A celebrated poet and statesman of the Sòng Dynasty, who lived from A.D. 1036–1101. He filled various official positions including that of President of the Board of Ceremonies. His poems and essays are of considerable merit, and are published to this day under the title of 東坡全集.

Sun

(日)

“The Sun, defined by the  文 as corresponding to 實 that which is solid or complete, and hence the symbol of the sovereign upon earth. The great luminary is represented as the concreted essence of the masculine principle in nature 陽 and the source of all brightness. From it emanate five colours. It is 1,000 li in diameter, 3,000 li in circumference, and suspended 7,000 li below the arch of the firmament. The 山海經 asserts that the Sun is the offspring of a female named Yì Hé (義和).”253 There is a legend to the effect that the chariot of the Sun is harnessed to six dragons driven by the Goddess Yì Hé.

文 as corresponding to 實 that which is solid or complete, and hence the symbol of the sovereign upon earth. The great luminary is represented as the concreted essence of the masculine principle in nature 陽 and the source of all brightness. From it emanate five colours. It is 1,000 li in diameter, 3,000 li in circumference, and suspended 7,000 li below the arch of the firmament. The 山海經 asserts that the Sun is the offspring of a female named Yì Hé (義和).”253 There is a legend to the effect that the chariot of the Sun is harnessed to six dragons driven by the Goddess Yì Hé.

A fabulous being known as Yù Huā (驚 ) is said to dwell in the Sun, and in the language of Taoist mysticism the name of the Sun is Yù Yí (變儀). According to ancient Chinese philosophy Heaven is round and Earth is square. The sun, moon, and stars, which were worshipped in former times, are known as the Three Luminaries (三光), or the Three Regulators of Time (三辰). A common colloquial term for the sun is tàiyáng (太陽), or Great Male Principle, and the term rì (日), derived from an archaic figure depicting a dot within a circle, is not only applied to the sun, but also in the sense of one revolution of that body, or a day.

) is said to dwell in the Sun, and in the language of Taoist mysticism the name of the Sun is Yù Yí (變儀). According to ancient Chinese philosophy Heaven is round and Earth is square. The sun, moon, and stars, which were worshipped in former times, are known as the Three Luminaries (三光), or the Three Regulators of Time (三辰). A common colloquial term for the sun is tàiyáng (太陽), or Great Male Principle, and the term rì (日), derived from an archaic figure depicting a dot within a circle, is not only applied to the sun, but also in the sense of one revolution of that body, or a day.

“The red crow with three feet is the tenant of the solar disc, and is the origin of the triquetra symbol of ancient bronzes. Huái Nánzî, who died 122 B.C., grandson of the founder of the Hàn Dynasty and an ancient Taoist votary, says that the red crow has three feet because three is the emblem of the masculine principle of which the sun is the essence; the bird often flies down to Earth to feed on the plant of immortality.”254

The self-styled First Emperor (始皇帝), 259 B.C., offered sacrifices to the following Eight Gods (八神); 1, Lord of Heaven (天主); 2, Lord of Earth (地主); 3, Lord of War (兵主); 4, Lord of the Yang Principle (陽主); 5, Lord of the Yin Principle (陰主); 6, Lord of the Moon (月主); 7, Lord of the Sun (曰主); 8, Lord of the Four Seasons (四時主). The ceremonial worship of the firmament was last carried out by President Yuán Shìkâi (袁世 ), who unsuccessfully attempted to restore the Imperial form of government in 1916.

), who unsuccessfully attempted to restore the Imperial form of government in 1916.

It is believed that the Luó hou xïng (羅膜星) is an unlucky star which tries to devour the sun at the time of the eclipse. The evil spirit of this star is said to have retarded the birth of SHÂKYAMUNI BUDDHA (q. v.) for six years. The temple drums and gongs are loudly beaten and crackers exploded to prevent this demon from devouring the sun. An eclipse of the sun (曰食) was believed to bring about a loss of virtue on the part of the Emperor, of whom that luminary was the emblem.

Sometimes an enormous red sun is depicted on the “shadow wall” (影壁), placed before the gate of an official building as a bar to all noxious influences. Being typical of the pure and bright principle yáng, it daily suggests to the inmates of the establishment the desirability of pure and just administration (vide BEAST OF GREED, YIN AND YANG).

The Chinese year is divided into twenty-four solar terms or periods (氣), corresponding to the day on which the sun enters the first and fifteenth degree of one of the zodiacal signs. To each of these an appropriate name is given, as shown in the following table. Their places in the lunar calendar will change every year, but in the solar year they fall nearly on the same day in successive years. When an intercalary month occurs, they are still recorded as usual; but the intercalation is made so that only one period shall fall in it. The equinoxes and solstices, and some of the festivals, are regulated by the solar periods, some of which contain fourteen, and others sixteen days, their average length being fifteen days.

The sundial is symbolic of virtuous government. It is useless when obscured by clouds, so the ruling power is without effect if evil counsel intervenes. As the sun shines on high and low alike, the people should, similarly, be impartially treated.

Swallow

(燕)

The Chinese term for the swallow is a pictogram, or conventional representation of the bird, showing head, body, wings, and tail (vide Illustration: The Evolution of Chinese Writing, under WRITTEN CHARACTERS).

Hirundo gutturalis is the common house swallow so numerous in central and northern China. The Striped Swallow (花燕) or H. nipolensis and the Reed Swallow (盧燕) are also found, but the celebrated birds’ nest soup is made from the gelatinous nests of the Sea Swallow (海燕), or H. esculenta from the Malay Archipelago.

Peking (Peiping) is known as the City of Swallows (燕京) on account of the numbers of these birds which nest in the ancient buildings of the capital.“The coming of swallows and their making their nests in a new place, whether dwelling-house or store, are hailed as an omen of approaching success, or a prosperous change in the affairs of the owner or occupier of the premises.”255 Women’s voices are compared to the twittering of swallows, while the fragile nest of the bird (燕 ) is metaphorically applied to positions of insecurity and danger.

) is metaphorically applied to positions of insecurity and danger.

Swastika

( 字)

字)

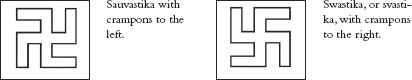

The fylfot, or swastika, is of great antiquity and is common to many countries. It was the monogram of Vishnu and Siva in India, the battle-axe of Thor in Scandinavian inscriptions, and a favourite symbol with the Peruvians. In China and Japan it would appear to be a Buddhist importation, though it may possibly be a variation of the meander (vide DIAPER PATTERNS). This emblem is to be seen on the wrappers of parcels, on the stomach or chest of idols, on the eaves of houses, on embroidery, and many other objects.

It has its crampons directed towards the right, but another form  , called Sauvastika, is directed to the left. The former is said to be the first of the 65 auspicious signs on the footprint of Buddha, and the latter the fourth. It is said by some authorities to have been impressed by each toe of the Buddha. Sometimes these toe impressions are represented by flowers or flames (vide FOOTPRINTS OF BUDDHA).

, called Sauvastika, is directed to the left. The former is said to be the first of the 65 auspicious signs on the footprint of Buddha, and the latter the fourth. It is said by some authorities to have been impressed by each toe of the Buddha. Sometimes these toe impressions are represented by flowers or flames (vide FOOTPRINTS OF BUDDHA).

The term Swastika, or Svastika, is derived from the Sanskrit su “well” and as “to be,” meaning “so be it,” and denoting resignation of spirit. It is styled the “ten thousand character sign,” wànzì (萬字), and is said to have come from Heaven. It is described as “the accumulation of lucky signs possessing ten thousand efficacies.” It is also regarded as the symbol or seal of Buddha’s heart (佛心印), and is usually placed on the heart of SHÂKYAMUNI BUDDHA (q. v.) in images of pictures of that divinity, as it is believed to contain within it the whole mind of Buddha (vide HEART). It appears as an ornament on the crowns of the Bonpa and Lama deities of Thibet. It may, after all, be nothing more or less than a variety of the MYSTIC KNOT (q. v.).

“According to Burnouf, Schliemann, and others, the Swastika represents the ‘fire’s cradle,’ i. e., the pith of the wood, from which in oldest times in the point of intersection of the two arms the fire was produced by whirling round an inserted stick. On the other hand, according to the view most widespread at the present day, it simply symbolises the twirling movement when making the fire, and on this, too, rests its application as symbol of the sun’s course.”256 The Latin cross, 十; the Greek Tau,  ; the St. Andrew’s cross, ×; the “Mirror of Venus,”

; the St. Andrew’s cross, ×; the “Mirror of Venus,”  ; the “Key of the Nile,”

; the “Key of the Nile,”  etc. are also said to have been borrowed from the same source, i. e., the Aryan or Vedic sun and fire worship. The Swastika is sometimes represented in a circle, and this circle undoubtedly symbolises the sun, while the crossing lines are also emblematic of the rays of that luminary. It is frequently employed in ornamental border designs, in carpets, silk embroideries, carved woodwork, etc.

etc. are also said to have been borrowed from the same source, i. e., the Aryan or Vedic sun and fire worship. The Swastika is sometimes represented in a circle, and this circle undoubtedly symbolises the sun, while the crossing lines are also emblematic of the rays of that luminary. It is frequently employed in ornamental border designs, in carpets, silk embroideries, carved woodwork, etc.

A number of bronze and brass crosses about the size of belt buckles have been unearthed in the Ordos district of North China. These tokens are nearly all different, and chiefly take the form of the Christian cross, though the swastika is also in evidence in many of them. It is possible that they may have had a religious significance, or that they were used as military medals, secret society emblems, or merely as amulets of good fortune.

Sword

(劍)

In ancient times there were many celebrated swordsmiths in China, the best known being Chï Yóu (蛋尤), 2600 B.C., and Gān Jiàng (干將), who lived in the State of Wû in the 3rd century B.C., and is said to have forged various “magic” swords of steel, which were regarded as supernatural because they were so much sharper than the bronze weapons previously used in warfare. There is a rock in Jiāxìng (嘉興) apparently divided into two sections, concerning which tradition says that Gān Jiàng there tried the metal of his blade by splitting the stone asunder.

In Buddhism, the sword, Sanskrit Adi, is emblematic of wisdom and penetrating insight, and its purpose, in the hands of the deities, is to cut away all doubts and perplexities and clear the way for knowledge of the truth. In Taoism it is symbolic of victory over evil, and is the emblem of Lû Dòngbïn (呂洞賓), one of the EIGHT IMMORTALS (q. v.), who, armed with his magic sword, traversed the earth subduing the powers of darkness.