Tàijí

(太極)

“Chinese philosophers speak of the origin of all created things under the name of tàijí. This is represented in their books by a figure, which is thus formed: On the semi-diameter of a given circle describe a semi-circle, and on the remaining semi-diameter, but on the other side, describe another semi-circle. The whole figure represents the tàijí, and the two divided portions, formed by the curved line, typify what are called the yīn (陰) and the yáng (陽), in respect to which, this Chinese mystery bears a singular parallel to that extraordinary fiction of Egyptian mythology, the supposed intervention of a masculo-feminine principle in the development of the mundane egg. The tàijí is said to have produced the yáng and the yīn, the active and passive, or male and female principle, and these last to have produced all things,” 257 The circle represents the origin of all created things, and when split up into two segments, it is said to be reduced to its primary constituents, the male and female principles.

The tàijí is said to be the essence of extreme virtue and perfection in heaven and earth, men and things. Speaking figuratively it is like the ridge-pole of a house, or the central pillar of a granary, being always in the middle of the building, and the whole structure on every side depends upon it for support.

From the tàijí, which may be called the Great Extreme or Ultimate Principle, composed of the YIN AND YANG (q. v.), springs the FIVE ELEMENTS (q. v.), which are the source of all things, and man, having been evolved from the union of the male and female principles, is enriched at his birth by the possession of the Five Virtues (五常), viz. : Benevolence (仁); Purity (義); Propriety (禮); Wisdom (智); and Truth (信).

The tàijí surrounded by the EIGHT DIAGRAMS (q. v.), is a common design of good omen, and is frequently painted above the doors of Chinese houses as a charm against evil influences (vide EIGHT DIAGRAMS, YIN AND YANG).

Tea

(茶)

The tea-plant, which is chiefly grown in Fukien, Chekiang, and Kuangtung, is not indigenous to China, and is said to have been imported in A.D. 543 by an ascetic from northern India, and in the ninth century it was in general use as a national beverage. Tea was first introduced into Europe towards the close of the sixteenth century by the Dutch.

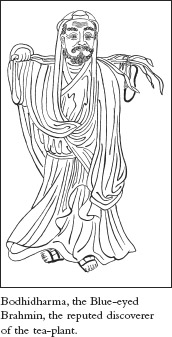

Bodhidharma, or Dá Mó (達摩), the Blue-eyed Brahmin, was an Indian Buddhist missionary of royal descent, who reached China in A.D. 526, and is regarded as the chief of the Six Patriarchs (六祖) of the Buddhist religion. He is identified by some with St. Thomas the Apostle. His doctrine was that perfection must be sought in the inward meditations of the heart rather than in outward deeds and observances, and his miraculous crossing of the Yangtze on a reed has formed the theme of many painters and sculptors. It is recorded that once when he sat in meditation, sleep overcame him; and on waking, that it might never happen again, he cut off his eyelids. But they fell on the earth, took root, and sprouted; and the plant that grew from them was the first of all tea-plants—the symbol (and cause!) of eternal wakefulness.

The word “tea” is said to be derived from the Fukienese pronunciation te, and “that excellent, and by all Physitians approved, China Drink, called by the Chineans Tcha, by other Nations Tay alias Tee,” was advertised for sale three centuries ago (in the Weekeley Newes, 31 January, 1606) at the Sultaness Head, a coffee house in Sweetings Rents, near the Royal Exchange, London. The Chinese term chá (茶), “tea,” is said to be identical with kûchá (苦 探), or tú (茶), “chicory,” often referred to in the Classics, but during the reign of a prince of the Hàn Dynasty the later name for tea was interdicted, and is now chiefly used to signify “poison”. The classical term míng (若) was introduced during the Táng Dynasty, and is still employed in literary composition; it originally denoted the late pickings of the tea-plant. Shè (藉) and chuân (碑) are other names for coarse teas. Lù Yû (陸 羽), who died in A.D. 804, was the author of the “Tea Classic” (茶 經), a famous work on Tea, and is worshipped by the tea-planters as their tutelary deity.

The time for sowing tea seeds is about the month of September. Holes are dug, each hole being about three feet square, and nine or ten seeds are planted in each hole. When the seedling has grown to the height of a few inches the planter clears away any grass that may be growing round it. . . . The best tea generally grows on high mountain peaks, where fogs and snow prevail, which gives a better flavour to the leaves.”258 “The tea-plant yields its first crop at the end of the third year, and thereafter three or four crops are taken annually. The first picking takes place while the leaf is still unfolded.”259

The tea-shrub of Central China is the Thea chinensis, or Thea viridis of the botanists, and the leaves are perhaps more lanceolate than those of the Thea Cantoniensis, or Thea assamica, of the southern regions. “As a result of long cultivation and promiscuous planting, there is hardly a tea garden but is mainly filled with hybrids between these two species.”260 “Both the green and the black, or reddish, varieties of tea-leaf may be produced from either plant. The leaves are picked at three or more occasions in the year, the first picking, which is the best, taking place in April. The leaves are slightly dried in the sun, crushed by the feet of coolies in tubs, in order to get rid of the useless watery juices, and to give a twist to the leaf. The leaf undergoes a series of heatings at a low temperature, is winnowed, picked and packed in lead-lined chests which are arranged in ‘chops’ of from four hundred to six hundred and fifty chests.”261

“The adulterants of tea are extremely numerous, and the Chinese show great skill in this direction. Among adulterants that are used are the leaves of the ash, plum, dog-rose, Rhamus spp., Rhododendron ssp., and Chrysanthemum ssp., as well as tea stalks and paddy husks. The scented flowers of the Olea fragrans, Chloranthus inconspicuus, Aglaia odorata, Camellia Susanqua, Gardenia florida, Jasminum Sambac and other species, are used to give fragrance to inferior qualities. Sometimes the true tea is almost replaced by a factitious compound known as ‘lie tea’ which is composed of a little tea dust blended with foreign leaves, sand and magnetic iron by means of a solution of starch, and coloured with graphite, turmeric, indigo, Prussian blue or China clay, according to the kind of tea it is desired to simulate.”262 The leaves of the Sageretia theezans (積), together with those of the willow, poplar, and spiroea, provide the poor with passable substitutes for tea.

Brick tea (縛茶) is made of tea dust steamed and pressed into hard cakes. The Camellia oleifera (山茶) also belongs to the genus Thea (order Ternstroemiaceæ), and yields the so-called tea-oil (茶油), which is expressed from the seeds.

“Tea is described in the Bên Câo (本草), or Herbal, as cooling, peptic, exhilarating, rousing, both laxative and astringent, diuretic, emmenagogue, and, in large concentrated doses, emetic. Taken in large quantities for a long time it is believed to make people thin and anaemic. Weak tea is a favourite wash for bad eyes and sore places. Tea-seeds (茶子) are said to benefit coughs, dyspnoea, and singing in the head.”263

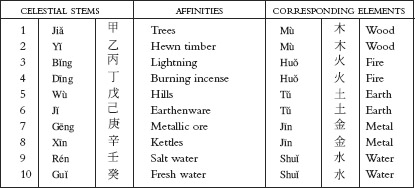

Ten Celestial Stems

(十天干)

The Ten Celestial Stems, shítiāngàn, are the ten primary signs which, when used in combination with the TWELVE TERRESTRIAL BRANCHES (q. v.), form the CYCLE OF SIXTY (q. v.); they form the masculine or primary, i. e, left hand column of the cycle. The following table shows their names, affinities, and corresponding elements (vide also FIVE ELEMENTS):

The first of the Twelve Terrestrial Branches is joined to the first of the Ten Celestial Stems until the last or tenth of the latter is reached, when a fresh commencement is made, the eleventh of the series of twelve branches (戌) being next appended to the first stem (甲). This system is applied to the numbering of hours, days, months, and years (vide also SUN and MOON). The application of the method to the successive days has been traced to Dà Náo (大燒), 27th century B.C., and the similar numbering of years is attributed to Wáng Mâng (王莽), 33 B.C., but signs of its employment at a somewhat earlier date have been discovered.

“The cyclical signs play a great part in Chinese divinations, owing to their supposed connection with the elements or essences which are believed to exercise influence over them in accordance with the order of succession represented above.”264

Thigh-bone Trumpet

(腿骨嗽八)

A trumpet made from a human thigh-bone, and used by the priests of Lamaism for the purpose of summoning the spirits.

In the preparation of these thigh-bone trumpets the bones of criminals or those who have died by violence are preferred. (Vide also SKELETON STAFF.)

Three Great Beings

(三 士)

士)

A well-known set of images is called Sān Dà Shì, or the Three Great Beings. These are three Bodhisattvas (Skt.), or Púsà (Chinese), namely Manjusri (Skt.) or Wéng Shü, Samantabhadra (Skt.) or Pû Xián, and Avalokitesvara (Skt.) or Kuan Yin.

The 83rd chapter of the popular work Xiùqiáofēngshényânyì (編橋圭可神演義) refers to this category of deities, and also to their power over the animal kingdom, or the forces of nature. (Vide separate articles under MANJUSRI, PU XIAN and KUAN YIN).

Three Pure Ones

(三清)

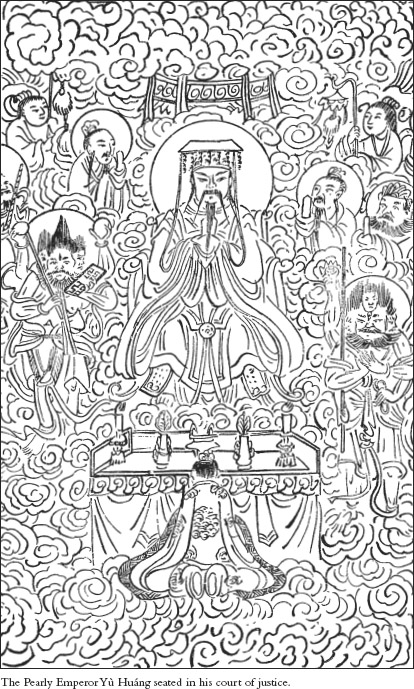

The Three Pure Ones are the deities of the Taoist trinity, and live in separate heavens. The supreme Master of the God is the Jade Ruler, or the Pearly Emperor, Yù Huáng (玉皇), who has been identified with Brahma and Indra, though the Buddhists claim that the Taoists have simply stolen their god Yù Dì. The second Pure One is Dào Jün (道君), of whom little is known beyond that he controls the relations of the YIN AND YANG (q. v.), or principles of nature, and dwells beyond the North Pole, where he has existed from the beginning of the world. The third is LAOCIUS (q. v.). Wayside shrines in honour of this trinity are perhaps more common than any others.

Yù Huáng is said to have been the son of an Emperor called Qïng Dì (清帝), whose consort Bâo Yuèguāng (寶月光) implored the gods to grant them a child. Her prayers were accepted and “when the birth took place a resplendent light poured forth from the child’s body, which filled the country with brilliant glare. His entire countenance was super-eminently beautiful, so that none became weary in beholding him. When in childhood he possessed the clearest intelligence and compassion, and taking the possessions of the country and the funds of the treasury, he distributed them to the poor and afflicted, the widowers and widows, orphans and childless, the houseless and sick, halt, deaf, blind and lame. Not long after this the demise of his father took place, and he succeeded to the government; but reflecting on the instability of life, he resigned his throne and its cares to his ministers, and repaired to the hills of Buming, where he gave himself up to meditation, and being perfected in merit ascended to heaven to enjoy eternal life. He however descended to earth again eight hundred times, and became the companion of the common people to instruct them in his doctrines. After that he made eight hundred more journeys, engaging in medical practice and successfully curing the people; and then another similar series, in which he exercised universal benevolence in hades and earth, expounded all abstract doctrines, elucidated the spiritual literature, magnanimously promulgated the renovating ethics, gave glory to the widely-spread merits of the gods, assisted the nation, and saved the people. During another eight hundred descents he exhibited patient suffering; though men took his life, yet he parted with his flesh and blood. After this he became the first of the verified golden genii, and was denominated the pure and immaculate one, self-existing, of highest intelligence.”265

Yù Huáng has also been taken to be the subject of a nature myth, on account of the meaning of the names of his parents (vide supra), viz., “Brilliance” and “Moon-light”, or the sun and the moon, whose union symbolizes the revival of spring.

Thunderbolt

(箭石)

Sanskrit Vajra. The Thunderbolt is the emblem of the divine force of Buddha’s doctrine which shatters all false beliefs and mundane wickedness (vide DIAMOND MACE). The emblem representing the Thunderbolt is often grasped in the hand of Buddhist images (vide Illustration under LAMAISM).

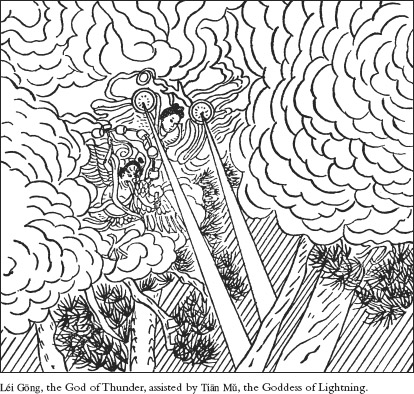

Thunder occurring in unusual and unseasonable times is considered by the Chinese as ominous of some political change, such as a revolution, etc. Wicked persons are said to be killed by the God of Thunder (雷公), and the Goddess of Lightning (電母) flashes light on the intended victim to enable her colleague, the God of Thunder, to launch his deadly bolt with accuracy (vide also GOD OF FIRE). The God of Thunder is “almost the only Chinese mythological deity who is drawn with wings. The cock’s head and claws, the hammer and chisel, representing the splitting peal attending a flash, the circlet of fire encompassing a number of drums to typify the reverberating thunder and the ravages of the irresistible lightning, present a grotesque ensemble which is quite unique even among the bizarrerie of oriental figures.”266 He was originally represented, in the 1st century B.C., according to Wáng Chōng (王充) in his Lùn Héng (論衡), as a strong man, not a bird, with one hand dragging a cluster of drums, and brandishing a hammer with the other. His present birdlike form would appear to have been evolved through the medium of Buddhism, from the Indian Garuda, a divine being, half man and half bird, having the head, wings, beak and talons of an eagle, and human body and limbs, its face being white, its wings red, and its body golden. The Garuda served as an aerial courser for the Hindu God Vishnu. The “Thunderer” also bears some resemblance to the Indian God Vajrâpani who in one form appears with Garuda wings.

Thunderbolt-dagger

(雷電刀)

Sanskrit, Phurbu. A dagger of wood or metal to stab the demons. The central portion is in the form of a vajra —thunderbolt (vide DIAMOND MACE, THUNDERBOLT), which is the part held in the hand, and the hilt-end is terminated either by a fiend’s head, or by the same surmounted by a horse’s head, representing the horse-headed tutelary devil of Lamaism, Tamdin, Sanskrit, Hayagriva. This emblem of authority is seen in the hands of Buddhist and Lama deities (vide Illustration under LAMAISM).

Tiger

(虎)

Tigers were very common in ancient times, and are still to be found in Kuangtung, Kuangsi, Fukien, Kiangsi, and Manchuria. The largest variety runs to twelve feet in length.

The written symbol for this animal consists of the radical hû (虎), which is the representation of the tiger’s stripes, while the form ér (ル), man, below, implies that the beast rears up on its hind legs like a human being erect.

“The tiger is called by the Chinese the king of the wild beasts, and its real or imaginary qualities afford them matter for more metaphors than any other wild animals. It is taken as the emblem of magisterial dignity and sternness, as the model for the courage and fierceness which should characterize a soldier, and its presence or roar is synonymous with danger and terror. Its present scarceness has tended to magnify its prowess, until it has by degrees become invested with so many savage attributes that nothing can exceed it. Its head was formerly painted on the shields of soldiers, on the wooden covers of the port-holes of forts to terrify the enemy, on the bows of revenue cutters, and embroidered upon court robes as the insignia of some grades of military officers. The character hû has been numbered as one of the radicals of the language, and the words comprised under it are nearly all descriptive of some quality appertaining to the tiger.... Virtues are ascribed to the ashes of the bones, to the fat, skin, claws, liver, blood, and other parts of a tiger, in many diseases; the whiskers are said to be good for toothache. . . . In the days of Marco Polo, the multitude of tigers in the northern parts of the empire rendered travelling alone dangerous.”267

“Just as the dragon is chief of all aquatic creatures, so is the tiger lord of all land animals. These two share the position of prime importance in the mysterious pseudo-science called FENG SHUI (q. v.). The tiger is figured on many of the most ancient bronzes, and its head is still reproduced as an ornament on the sides of bronze and porcelain vessels, often with a ring in its mouth. It frequently appears in a grotesque form which native archaeologists designate a ‘quadruped’ (獸). The tiger symbolises military prowess. It is an object of special terror to demons, and is therefore painted on walls to scare malignant spirits away from the neighbourhood of houses and temples.”268 The shoes of small children are often embroidered with tiger’s heads for the same reason. The God of Wealth is sometimes represented as a tiger, and tiger gods are also to be found, chiefly in Hanoi and Manchuria, where the animals are most plentiful. In former times Chinese soldiers were occasionally dressed in imitation tiger-skins, with tails and all complete. They advanced to battle shouting loudly, in the hope that their cries would strike terror into the enemy as if they were the actual roars of the tiger.

“According to the astrologers, the star (a. of Ursa Major) gave birth by metamorphosis to the first beast of this kind. He is the greatest of four-footed creatures, representing the masculine principle of nature, and is the lord of all wild animals (山獸之君). He is also called the King of Beasts (獸中王), and the character 王 (King) is believed to be traceable upon his brow. He is seven feet in length, because seven is the number appertaining to yáng, the masculine principle, and for the same reason his gestation endures for seven months. He lives to the age of one thousand years. When five hundred years old, his colour changes to white. His claws are a powerful talisman, and ashes prepared from his skin worn about the person act as a charm against sickness. Bái Hû (白虎), the White Tiger, is the name given to the western quadrant of the Uranosphere and metaphorically to the West in general.”269 The title of White Tiger was bestowed on the canonized Yin Zhengxiu, a general of the last Emperor of the Yïn Dynasty. His image may be seen at the door of Taoist temples.

The tiger represents the third of the TWELVE TERRESTRIAL BRANCHES (q. v.). This animal is said by Chinese writers “to eat its victims by the Chinese calendar, and to have the power of planning out the country round its lair, to be visited according to a fixed system. If it leaps up three times at its prey, and fails, it withdraws. Its victims become devils after digestion, but the flesh of the dog is said to intoxicate this catlike creature. Bad smells, such as burnt horn, are said to scare it away, and the hedgehog, or tenroc, is said to be able to get the better of it.”270

According to the Chinese belief, the spirit of a person eaten by a tiger urges the beast to devour others; those who have met a violent death may return to the world, if fortunate enough to secure a substitute. According to Kāng Xï’s dictionary, when a tiger bites a man in such a way that death ensues, the man’s soul has no courage to go elsewhere, but regularly serves the tiger as a slave, and is called a zhàng (虎經

死。魂不敢他 適。輒線事虎 。名 曰恨 。). The same idea of seeking a substitute (討替) is the explanation of the objection by supersitious persons to save a drowning man, lest they themselves should be dragged down as a substitute by the spirit of one previously drowned there, who, it is supposed, is endeavouring to secure a substitute and thereby effect his own escape.

死。魂不敢他 適。輒線事虎 。名 曰恨 。). The same idea of seeking a substitute (討替) is the explanation of the objection by supersitious persons to save a drowning man, lest they themselves should be dragged down as a substitute by the spirit of one previously drowned there, who, it is supposed, is endeavouring to secure a substitute and thereby effect his own escape.

Toad

(暇膜)

Frogs and toads are very common in China, especially in the irrigated paddy-fields where they combine to produce a vociferous chorus during the breeding season in the early summer.

The Chinese do not appear to distinguish very clearly between the frog and the toad. The spawn of the frog is believed to fall from heaven with the dew, and hence the frog is called the “heavenly chicken” (天雞). It is used as an article of diet. A kind of medicine, said to be similar in its physiological action to digitalis, is obtained from the Chinese toad, Bufo asiaticus, in the following manner. The toad is held firmly in one hand, while the biggest wart-like swelling just behind the eye is touched lightly with a hot iron, whereupon a whitish juice is exuded by the toad. This is scraped off and put on to a glass plate, and another toad is taken and the operation repeated, till there is a good supply of the white juice. This is then allowed to evaporate slowly to a powder, which is used to make up into pills and solutions as a heart remedy.

As in the other countries, many stories and superstitions have been connected with the toad, owing no doubt to its weird and warty appearance, and the length of its life, which may extend to thirty or forty years. The three-legged toad of Chinese mythology is said to exist only in the moon, which it swallows during the eclipse. It has therefore come to be the emblem of the unattainable. The legendary Chieftain Hòu Yì (后拜), circa 2500 B.C., obtained the Elixir of Immortality (無死之藥) from Xï Wáng Mû (西王母); Cháng É (婦 娥), his wife, stole it and fled to the moon, where she was changed by the gods into a toad (膽餘), whose outline is traced by the Chinese on the moon’s surface. Liú Hâi (劉海), a Minister of State of the 10th century A.D., was a proficient student of Taoist magic. He was said to possess a specimen of the mystical three-legged toad, which would convey him, like Bucephalus, to any place he wished to go. Occasionally the creature would escape down the nearest well, but Liú Hâi had no difficulty in fishing it out by means of a line baited with gold coins. He is popularly represented with one foot resting on the toad, and holding in his hand a waving fillet or ribbon upon which five gold cash are strung. This design is known as “Liú Hâi sporting with the Toad” (劉海戲膽), and is regarded as most auspicious and conducive to good fortune, the three-legged toad being also considered to be the symbol of money-making. Another version of the story is that this toad lived in a deep pool and exuded a poisonous vapour which injured the people. Liú Hâi is said to have hooked the ugly and venomous creature with a gold cash and destroyed it. Hence this legend points the moral that money is the fatal attraction which lures men to their ruin.

Zhāng Guólâo (張果老), one of the EIGHT IMMORTALS (q. v.) of Taoism, is sometimes depicted riding on a colossal batrachian. An ancient form of Chinese script is known as the Tadpole Character (嫩虫斗字), so called from its resemblance to tadpoles swimming about in water.

Tortoise

(龜)

The written symbol for this reptile is a pictogram showing the snakelike head above, the claws on the left, the shell on the right, and the tail below (vide Illustration: “The Evolution of Chinese Writing,” under WRITTEN CHARACTERS).

“Tortoises are kept in tanks in Buddhist temples, and it is considered very meritorious to feed them, or to add to their number by purchasing them alive from the stalls of the street, where they are constantly exposed for sale as food. When a tortoise is thus purchased, a hole is made in the shell, and a creature with several such holes, often filled with rings, is much prized for medicinal purposes. Jelly made from the plastron, or the powdered shell made into pills or mixed up in cakes, is reputed to be tonic, cordial, astringent, and arthritic, and very useful in diseases of the kidneys.”271 Tortoiseshell (批壇) is chiefly obtained from the hawk’s bill turtle (Chelonia imbricata), which is found in the Malay Archipelago and the Indian Ocean, and imported for carving and inlaying purposes at Canton. The soft-shelled fresh water turtle, Trionyx sinensis, is a common article of diet. The Large-headed Tortoise, Platysternum megacephaluf, is found in South China. The Chinese employ the tortoise to open up gutters and drains, as it is fond of burrowing in the earth. The tortoise is “vulgarly known (1) as wángbā (王八), from a nickname given by the people of the village to Wang Jian, who after a youth spent in violence and rascality, became the founder of the Earlier Shu State, dying A.D. 918; or (2) as wàngbā (忘八), ‘the creature that forgets the eight rules of right and wrong— viz., politeness, decorum, integrity, sense of shame, filial piety, fraternal duty, loyality and fidelity (禮義廉恥孝梯忠信)—from a superstitious belief in the unchastity of the female. Hence, wángbā is a common term of abuse, equivalent to cuckold.”272

According to the “Book of Rites” (禮記), the unicorn, phoenix, tortoise, and dragon are “the four spiritually endowed creatures”(四靈). The tortoise is sacred to China, and is an emblem of longevity, strength, and endurance. It was said to be an attendant of PAN GU (q. v.) when he chiselled out the world. Under the name of the “Black Warrior” (玄武) it presides over the Northern Quadrant of the uranoscope and symbolises winter.“The tortoise symbolises the universe to the Chinese as well as the Hindus. Its dome-shaped back represents the vault of the sky, its belly the earth, which moves upon the waters; and its fabulous longevity leads to its being considered imperishable.”273 “The guï or tortoise is the chief of all shelly animals,‘because its nature is spiritual.’The upper vaulted part of its shell (蔡), says the Bên Câo (本草), has various markings corresponding to the constellations in the heavens, and is the yáng ; the lower even shell has lines answering to the earth, and is the y ï n (vide YIN AND YANG). The divine tortoise has a snake’s head, and a dragon’s neck; the bones are on the outside of the body, and flesh within; the intestines are joined to the head. It has broad shoulders and a large waist; the sexes are known by examining the lower shell. The male comes out in spring, when it changes its shell, and returns to its torpid state in the winter, which is the reason that the tortoise is very long-lived. Chinese authors describe ten sorts of tortoise; one of them is said to become hairy in its old age, after long domestication. Another has its shell marked with various lines resembling characters, and it is the opinion among some of the Chinese that their writing was first suggested by the lines on the tortoise shell (vide EIGHT DIAGRAMS), and the constellations of the sky. The shell was employed in divination and fortune-telling.”274

“Divers marvellous tales are narrated with regard to its fabulous longevity and its faculty of transformation. It is said to conceive by thought alone, and hence the ‘progeny of the tortoise,’ knowing no father, is vulgarly taken as a synonym for the bastard-born. A species of the tortoise kind is called biē (籠), the largest form of which is the yuán (電), in whose nature the qualities of the tortoise and the dragon are combined. This creature is the attendant of the god of the waters (河伯使者), and it has the power of assuming divers transformations. In the shape of the tortoise is also depicted the bïxï ( ), a god of the rivers (河神), to whom enormous strength is attributed; and this supernatural monster is frequently sculptured in stone as the support of huge monumental tablets planted immovably as it were, upon its steadfast back. The conception is probably derived from the same source with that of the Hindoo legend of the tortoise supporting an elephant, on whose back the existing world reposes.”275

), a god of the rivers (河神), to whom enormous strength is attributed; and this supernatural monster is frequently sculptured in stone as the support of huge monumental tablets planted immovably as it were, upon its steadfast back. The conception is probably derived from the same source with that of the Hindoo legend of the tortoise supporting an elephant, on whose back the existing world reposes.”275

The “Record of Science’ (格物志) puts the age limit of the tortoise at 1,000 years. Wáng Chōng (王充), however, states in his “Lùn Héng ” (論衝), “When the tortoise has lived 300 years, it is no bigger than a coin, and may still walk on a lotus leaf; when 3,000 years old, its colour is blue with green rims, and it is then only one foot two inches in size” (龜生三百

如錢。游於蓮葉之上。三千

如錢。游於蓮葉之上。三千 色青邊綠。巨尺二寸).

色青邊綠。巨尺二寸).

It is said that the wooden columns of the Temple of Heaven at Peking were originally set on live tortoises, under the belief that as these animals are supposed to live for more than 3,000 years without food and air, they are gifted with miraculous power to preserve the wood from decay.

Trees

(樹)

Although a poetic appreciation of the beauty of trees and the luxuriance of their flowers and foliage has always been a characteristic of the Chinese people, yet, on account of the necessity for the provision of abundant fuel, and the high cost of wood as a building material, a continual process of deforestation has greatly reduced the timber supply of the country. The philosopher Mencius said, “The trees of the Ox Hill were once beautiful. Being situated, however, on the borders of a large State, they were hewn down with axes and bills; and could they retain their beauty?. . . It looks barren now, and people think it was never finely wooded, but is this the natural state of the hill?” (孟 日°牛山之木嘗美矣。以其效

日°牛山之木嘗美矣。以其效 於國斧斤伐之°可以爲美乎°

於國斧斤伐之°可以爲美乎° 見其濯濯也°以爲未嘗有林焉°此豈山之性也哉). The “Book of Poetry” (詩經) contains an ode referring to the period of Wên Wang (a contemporary of Saul), and the sentiment expressed is reminiscent of Morris’ lines beginning “Woodman, spare that tree!”:

見其濯濯也°以爲未嘗有林焉°此豈山之性也哉). The “Book of Poetry” (詩經) contains an ode referring to the period of Wên Wang (a contemporary of Saul), and the sentiment expressed is reminiscent of Morris’ lines beginning “Woodman, spare that tree!”:

“O fell not that sweet pear-tree!

See how its branches spread;

Spoil not its shade,

For Shào’s chief laid

Beneath it his weary head.”

(蔽甫甘棠 ° 勿剪勿代 ° 召伯所 )

)

In spite of this injunction the tree has completely vanished, not even leaving a legend as to where it may once have stood. Lord Shào dispensed justice out in the open beneath the trees, which was held sacred for some time after his death.

The general destruction of forests bears fruit in the train of calamities due to flood, or drought, consequent on the removal of Nature’s covering of the earth. Of recent years, however, the Chinese government has recognised that forestry is of prime importance, and has taken steps to check the wholesale demolition of the trees of the country.

Tree-worship was widely spread throughout China in ancient times, as is evidenced by the reluctance of the people to cut down trees in the neighbourhood of temples and graves, and the fact that a shrine to some local god is often placed at the roots or in the fork of a tree remarkable for its size and beauty. It is believed that the soul of the god resides in the tree, which is therefore held to be sacred, and if dug up or cut down, the person doing so is liable to die. “Orthodox Buddhism decided against the tree-souls, and consequently against the scruple to harm, declaring trees to have no mind nor sentient principle, though admitting that certain devas or spirits do reside in the body of trees and speak from within them.”276 Binding trees with garlands, and decorating their branches with lanterns, is part of the old tree-worship, the tree being also a phallic emblem. Reference to trees that bleed, and utter cries of pain or indignation when hewed down, occur very often in Chinese literature. China is not unique, however, in superstition regarding trees; in England the elder trees of Sussex, which used to be sacred to Pan in pre-Christian times, must never be cut down, and the result is that they grow in many inconvenient spots. Tamarisks, which flourish along the southern coast, are never brought into the house, and tamarisk hedges are left untrimmed, a relic of the ancient Egyptian belief that tamarisks grew over the grave of Osiris. Many forms of tree worship survive, the decoration of houses with holly at the Christmas season being one of them, and in many parts of England there is a strong superstition that hawthorn blossoms will cause death if brought indoors.

Magic virtues are ascribed to certain trees and plants. The leaves of the zhōngkuí (終奏), a kind of mallow, were reputed to have the power of warding off demons. A bunch of Artemisia (艾), a handful of the sword-shaped sweet flag— Acorus calamus (水葛蒲)—or a spray of willow leaves, is hung over the doors of houses to disperse evil influences on the 5th day of the 5th moon, the anniversary of the day when the rebel Huáng Cháo (

), who captured Chángān in A.D. 800, gave orders to his soldiers to slay all the inhabitants except certain favoured ones who exhibited a bunch of leaves at the door.

), who captured Chángān in A.D. 800, gave orders to his soldiers to slay all the inhabitants except certain favoured ones who exhibited a bunch of leaves at the door.

There are said to be eight trees called qiān ( ) or yàowáng (藥王)— the King of Drugs—in the moon, the leaves of which confer immortality on those who eat them. According to the Buddhist sutras a similar tree (藥 王 之 樹) grows in the Himalayas, and possesses the virtue of healing all diseases. A cassia-tree (桂) is also said to grow in the moon, and a man named Wú Gāng (

) or yàowáng (藥王)— the King of Drugs—in the moon, the leaves of which confer immortality on those who eat them. According to the Buddhist sutras a similar tree (藥 王 之 樹) grows in the Himalayas, and possesses the virtue of healing all diseases. A cassia-tree (桂) is also said to grow in the moon, and a man named Wú Gāng ( 剛), having committed an offence against the gods, was banished to the moon and condemned to the endless task of hewing down the tree. As fast as he dealt blows with his axe, the incisions in the trunk closed up again. Immortality is also the reward of these who eat of this tree (vide MOON).

剛), having committed an offence against the gods, was banished to the moon and condemned to the endless task of hewing down the tree. As fast as he dealt blows with his axe, the incisions in the trunk closed up again. Immortality is also the reward of these who eat of this tree (vide MOON).

The Chinese believe that if the Ailantus (臭捲) grows too high, the family living in the same courtyard will have bad luck. A mulberry should not be planted in front of a dwelling-house, nor a willow at the back, because sāng (桑), mulberry, has the same sound as sàng (喪), sorrow, and the willow, being symbolic of frailty and lust, may exercise an unhealthy influence on the ladies who generally occupy the rear apartments. The lilac, or dïngxiāngshù (丁香樹), should not be grown in a private residence, because dïng (釘) is also a nail, which implies family strife, friction, etc., amongst the womenfolk of the household. The cïméi (束梅) or wild rose, owing to its thorny nature, is also under a ban, because it may be a thorn of dissension in the family. Flogging is said to be necessary for a date-tree to keep it in order, and if the root of a grape-vine happens to shoot beneath the house it is said to be an omen of death. The cactus, xiānrénzhâng (仙人掌), literally the “fairy’s hand,” is considered unlucky to women who are about to bear children. A strip of red cloth of paper is often attached to a tree in order to prevent it from injury by the spirits of evil, who always avoid that particular colour of happiness and good fortune.

A conventional leaf resting on a fillet constitutes one of the EIGHT TREASURES (q. v.), used for ornamental purposes on porcelain, etc., and as an emblem of felicity. The cotyledon, or opening seed, is also a symbol of the germ of life. “All flesh is grass,” which, when found in abundance as a decorative motive, is supposed to represent the people.

The principal species of Chinese trees are treated separately in this book, and their respectively emblematic significances have also been fully dealt with.

Trident

(三股杖)

Three-pronged spears were formerly used by the Chinese in war and hunting. They are still used in processions, and may be seen in the hands of the Taoist idols. The Indian form of trident, Sanskrit, Trisula, is sometimes decorated with a miniature carved skull, or various religious emblems, and, when held in the grasp of the Buddhist deities, is regarded as the insignia of power and authority (vide SPEAR and Illustration under LAMAISM).

Twelve Ornaments

(十二章)

Many of the designs employed in the decoration of textile fabrics are undoubtedly of great antiquity. Among the earliest is a group of symbols known as the Twelve Ornaments, which signified authority and power, and were embroidered on vestments of state. They are as follows:

ON THE UPPER ROBE

1. 日 The SUN (q. v.) with a three-legged raven in it.

2. 月 The MOON (q. v.) with a hare in it, pounding the drug of immortality.

3. 星辰 The STARS (q. v.). Similar groups of three stars occur in Orion, Musca, Draco, etc.

4. 山 The MOUNTAINS—regarded with great appreciation by the Chinese, who hold some of them as sacred.

5. 龍 The examples of the DRAGON (q. v.).

6. 華蟲 The PHEASANT (q. v.).

ON THE LOWER ROBE

7. 宗葬 Two GOBLETS, with an animal on each.

8. 池遂 A spray of PONDWEED.

9. 火 Flames of FIRE (q. v.)—one of the FIVE ELEMENTS (q. v.).

10. 粉米 Grains of RICE (q. v.).

11. 髓 An AXE (q. v.).

12. 献 The figure YA 亞, said to be two 已 jî (self) back to back. Also described as the upper garment, which is cut square and hangs down back and front.

According to the Shü Jïng (書經), the Twelve Ornaments were referred to by the Emperor Shùn (舜) as being ancient even at that distant date—more than 2,000 years B.C. “I wish,” said the Emperor,“to see the emblematic figures of the ancients: the moon, the stars, the mountain, the dragon, and the flowery fowl, which are depicted on the upper garment; the temple-cup, the aquatic grass, the flames, the grains of rice, the hatchet, and the symbol of distinction, which are embroidered on the lower garment; I wish to see all these displayed with the five colours, so as to form the official robes; it is yours to adjust them clearly.”277 “Considering his ministers as his feet and hands, he was particularly anxious that the executors of his commands should be trustworthy and zealous. To remind them of their duty he pointed out to them symbols in their robes of state. Some had a sun, moon, and stars embroidered upon them. This, he said, points out the knowledge of which we ought to be possessed in order to rule well. The mountains indicate the constancy and firmness of which we stand in need; the dragon denotes that we ought to use every means to inspire the people with virtue; the beauty and variety of the colours of the pheasant remind us of the good example we ought to give, by practising the various virtues. In the upper robe, we behold six different kinds of embroidery, which are to remind us of the virtues to be engraved on our breast. The vase, which we are used to see in the hall of the ancestors, is a symbol of purity and disinterestedness; the fire, of zeal and love for virtue; the rice, of the plenty which we ought to procure for people; the hatchet is a symbol of justice in the punishment of vice; and the dresses, Fo and Fuh, are symbols of the discernment which we ought to have of good and evil.”278

Only the Emperor had the right to wear the complete set of twelve emblems painted or embroidered on his robes of ceremony.“The hereditary nobles of the first rank were restricted from the sun, moon, and the stars; those of the next two degrees were further restricted from mountains and dragons; and by a continually decreasing restriction five sets of official robes were made to indicate the rank of the wearers.279 These archaic figures are often found on porcelain and other works of art. “The two fû are among the commonest. The axe (髓) may be taken as the emblem of a warrior, but the original meaning of the other 職 is doubtful. It is used at the present day to signify ‘embroidered.’”280

Twelve Terrestrial Branches

(十二地支)

The Twelve Cyclical Signs, or Duodenary Cycle of Symbols, forming the feminine or secondary, i. e., right hand column of the CYCLE OF SIXTY (q. v.).

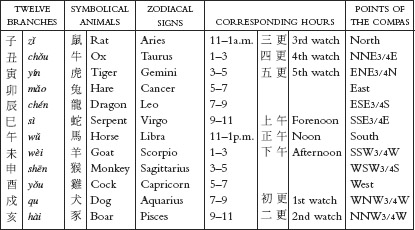

They are employed for chronological purposes and used to designate the hours, days, months, and years, being usually symbolised by twelve different animals (十二獸) or affinities (相屬), each of which is supposed to exercise some influence over the period of time denoted by the special character which the animal represents, as will be seen in the following table.

“The first explicit mention of the practice of denoting years by the names of animals as above is found in the history of the Táng Dynasty, where it is recorded that an envoy from the nation of the 酷蔓斯 (Kirghis?) spoke of events occurring in the year of the hare, or of the horse. It was probably not until the era of Mongol ascendancy in China that the usage became popular; but, according to Zhào Yì (趙翼)— A.D. 1727—traces of a knowledge of this method of computation may be detected in literature at different intervals as far back as the period of the Hàn Dynasty, or second century A.D. The same writer is of the opinion that the system was introduced at that time by the Tartar immigration.”281 Professor Chavannes has written a learned article to prove that the group known as the Twelve Animals was borrowed from the Turks, and was used in China as early as the first century of the Christian era (vide T‘oung-Pao, Vol. VII, 1906).

The zodiac of twelve is common to many nations of the East.“Every Chinese knows well under which animal he was born. It is essential that he should do so, for no important step throughout life is taken unless under the auspices of his particular animal. Indeed, this mysterious influence extends even beyond his life, and is taken into consideration in the disposal of his corpse.”282