ANY SEGMENT OF LAND—THE MOON, FOR EXAMPLE—CAN BE interesting of itself, but its greater significance must always lie in the life it sustains.

Toward dusk on a spring evening one hundred and thirty-six million years ago a small furry animal less than four inches long peered cautiously from low reeds which grew along the edge of a tropical lagoon that covered much of what was to be Colorado. It was looking across the surface of the water as if waiting for some creature to emerge from the depths, but nothing stirred.

From among the fern trees to the left there was movement, and for one brief instant the little animal looked in that direction. Shoving its way beneath the drooping branches and making considerable noise as it awkwardly approached the lagoon for a drink of water, came a medium-sized dinosaur, walking on two legs and twisting its short neck from side to side, as if on the watch for larger animals that might attack.

It was about three feet tall at the shoulders and not more than six feet in length. Obviously a land animal, it edged up to the water carefully, constantly jerking its short neck in probing motions. In paying so much attention to the possible dangers on land, it overlooked the real danger that waited in the water, for as it reached the lagoon and began lowering the forepart of its body so that it could drink, a fallen log which had lain inconspicuously half in the water, half out sprang into action.

It was a crocodile, well armored in heavy skin and possessed of powerful jaws lined with piercing teeth. It made a lunge at the drinking dinosaur, but it had moved too soon. Its well-calculated grab at the reptile’s right foreleg missed by a fraction, for the dinosaur managed to withdraw so speedily that the great snapping jaw closed not on the bony leg, as intended, but only upon the soft flesh covering it.

There was a ripping sound as the crocodile tore off a strip of flesh, and a sharp guttural click as the wounded dinosaur responded to the pain. Then peace returned. The dinosaur could be heard for some moments retreating. The disappointed crocodile swallowed the meager meal it had caught, then returned to its loglike camouflage, and the furry little animal returned to its earlier preoccupation of staring at the surface of the lagoon.

Its attention was poorly directed, for as it watched, it became aware, with a sense of terrible panic, of wings in the darkening sky, and at the very last moment of safety it threw itself behind the trunk of a ginkgo tree, flattened itself out, and held its breath as a large flying reptile swooped down, its gaping, sharp-toothed mouth open, and just missed its target.

Still flat against the moist earth, the little animal watched in terror as the huge reptile banked low over the lagoon and returned in what under other circumstances might have been a beautiful flight. This time it came straight at the crouching animal, but then, abruptly, had to swerve away because of the ginkgo roots. Dipping one wing, it turned gracefully in the air, then swooped down on another small creature hiding near the crocodile, unprotected by any tree.

Deftly the flying reptile snapped its beak and caught its prey, which uttered high shrieks as it was carried aloft. For some moments the little animal hiding in the ginkgo watched the flight of its enemy as the reptile dipped and swerved through the sky like a falling feather, finally vanishing with its catch.

The little watcher could breathe again. It was unlike the great reptiles, for they were cold-blooded and it was warm. They raised their babies from hatching eggs, while its came from the mother’s womb. It was a pantothere, one of the earliest mammals and progenitor of later types like the opossum, and it had scant protection in the swamp. Watching cautiously lest the flying hunter return, it ventured forth to renew its inspection of the lagoon, and after a pause, spotted what it had been looking for.

About ninety feet out into the water a small knob had appeared on the surface. It was only slightly larger than the watching animal itself, about six inches in diameter. It seemed to be floating on the surface, unattached to anything, but actually it was the unusual nose of an animal that had its nostrils on top of its head. The beast was resting on the bottom of the lagoon and breathing in this inventive manner.

Now, as the watching animal expected, the floating knob began slowly to emerge from the waters. It was attached to a head, not extraordinarily large but belonging obviously to an animal markedly bigger than either the first dinosaur or the crocodile. It was not a handsome head, nor graceful either, but what happened next displayed each of those attributes.

For the head continued to rise from the lagoon, higher and higher and higher in one long beautiful arch, until it stood twenty-five feet above the water, suspended at the end of a long and most graceful neck. It was like a ball extended endlessly upward on a frail length of wire, and when it was fully aloft, with no body visible to support it, the head turned this way and that in delicate motion, as if surveying the total world that lay below.

The small head and enormous neck remained in this position for some minutes, sweeping in lovely arcs of exploration. Apparently the small eyes which stood on either side of the projecting nose at the top of the skull were reassured by what they saw, for now a new kind of motion ensued.

From the surface of the lake an enormous construction began slowly to appear, an inch at a time, muddy waters falling from it as it rose. Slowly, slowly the thing in the lagoon came into view, until it disclosed a monstrous prism of dark flesh to which the prehensile neck was attached.

The body of the great reptile looked as if it were about twelve feet tall, but how far into the water it extended could not be discerned; it surely went very deep. Now, as the furry animal on shore watched, the massive body began to move, slowly and rhythmically. Where the neck joined the great dark bulk of the body, little waves broke and slid along the flanks of the beast. Water dripped from the upper part of the body as it moved ponderously through the swamp.

The reptile appeared to be swimming, its neck probing in sweeping arcs, but actually it was walking on the bottom, its huge legs hidden by water. And then, as it drew closer to shore and entered shallower water, there occurred a moment of marked grace and beauty. From the water trailing behind the animal, an enormous tail emerged. Longer than the neck and disposed in more delicate lines, it extended forty-four feet, swaying slightly on the surface of the lagoon. From head to tip of tail, the reptile measured eighty-seven feet.

Up to now it had looked like a long snake, floundering through the lagoon, but the truth was about to be revealed, for as the reptile advanced, the massive legs which had been supporting it became visible. They were enormous, four pillars of great solidity attached to the torso by joints of such crude construction that although the creature was amphibious, she could not easily support herself on dry land, where water did not buoy her up.

With slow, lumbering strides the reptile moved toward a clear river that emptied into the swamp, and now its total form was visible. Its head reared thirty-five feet; its shoulders were thirteen feet high; its tail dragged aft some fifty feet; it weighed nearly thirty tons.

It was diplodocus, not the largest of the dinosaurs and certainly not the most fearsome. This particular specimen was a female, seventy years old and in the prime of life. She lived exclusively on vegetation, which she now sought among the swamp waters. Moving her small head purposefully from one kind of plant to the next, she cropped off such food as she could find. This was not an easy task, for she had an extremely small mouth studded with minute peglike front teeth and no back ones for chewing. It seems incomprehensible that with such trivial teeth she could crop enough food to nourish her enormous body, but she did. It was this problem of chewing that had brought her toward the shore, this and one other strange impetus that she could not yet identify. She attended first to the chewing.

After finishing with such plants as were at hand, she moved into the channel. The mammal, still crouching among the roots of the ginkgo tree, watched with satisfaction as she moved past. It had been afraid that she might plant one of her massive feet on its nest, as another dinosaur had done, obliterating both the nest and its young. Indeed, diplodocus left underwater footprints so wide and so deep that fish used them as nests. One massive footprint might be many times as wide as the mammal was long.

And so diplodocus moved away from the lagoon and the apprehensive watcher. As she went she was one of the most totally lovely creatures so far seen on earth, a perfect poem of motion. Placing each foot carefully and without haste, and assuring herself that at least two were planted solidly on the bottom at all times, she moved like some animated mountain, keeping the main bulk of her body always at the same level, while her graceful neck swayed gently and her extremely long tail remained floating on the surface.

The various motions of her great body were always harmonious; even the plodding of the four gigantic feet had a captivating rhythm. But when the undulating grace of the long neck and the longer tail was added, this large reptile epitomized the beauty of the animal kingdom as it then existed.

She was looking for a stone. For some time she had instinctively known that she lacked a major stone, and this distressed her. She had become agitated about the missing stone and now proposed settling the matter. Keeping her head low, she scanned the bottom of the stream but found no suitable stones.

This forced her to move upstream, the delicate motion of her body conforming to the shifting bottom as it rose slightly before her. Now she came upon a wide selection of stones, but prudence warned her that they were too jagged for her purpose, and she ignored them. Once she stopped, turned a stone over with her blunt nose and scorned it. Too many cutting edges.

Her futile search made her irritable and she failed to notice the approach of a rather large land-based dinosaur that walked on two legs. He did not come close to approaching her in size, but he was quicker of motion, and had a large head, gaping mouth and a ferocious complement of jagged teeth. He was a meat-eater, always on the watch for the giant water-based dinosaurs who ventured too close to land. He was not large enough to tackle a huge animal like diplodocus if she was in her own element, but he had found that usually when the large reptiles came into the stream, there was something wrong with them, and twice he had been able to hack one down.

He approached diplodocus from the side, stepping gingerly on his two powerful hind feet, keeping his two small front feet ready like hands to grasp her should she prove to be in weakened condition. He was careful to keep clear of her tail, for this was her only weapon.

She remained unaware of her would-be attacker, and continued to probe the river bottom for the right stone. The carnivorous dinosaur interpreted her lowered head as a sign of weakness. He lunged at the spot where her vulnerable neck joined the torso, only to find that she was in no way incapacitated, for when she saw him coming she twisted adroitly, and presented the attacker with the broad and heavy side of her body. This repulsed him, and he stumbled back. As he did so, diplodocus stepped forward, and slowly swung her tail in a mighty arc, hitting him with such force that he was thrown off his feet and sent crashing into the brush.

One of his small front feet was broken by the blow and he uttered a series of awk-awks, deep in his throat, as he shuffled off. Diplodocus gave him no more attention and resumed her search for the right stone.

Finally she found what she wanted. It weighed about three pounds, was flattish on the ends and both smooth and rounded. She nudged it twice with her snout, satisfied herself that it was suited to her purposes, then lifted it in her mouth, raised her head to its full majestic height, swallowed the stone and allowed it to slide easily down her long neck into her gullet and from there into her grinding gizzard, where it joined six smaller stones that rubbed together gently and incessantly as she moved. This was how she chewed her food, the seven stones serving as substitutes for the molars she lacked.

With awkward yet attractive motions she adjusted herself to the new stone, and could feel it find its place among the others. She felt better all over and hunched her shoulders, then twisted her hips and flexed her long tail.

Night was closing in. The attack by the smaller dinosaur reminded her that she ought to be heading back toward the safety of the lagoon, back where fourteen other reptiles formed a protective herd, but she was kept in the river by a vague longing which she had experienced several times before, but which she could not remember clearly. She had, like all members of the diplodocus family, an extremely small brain, barely large enough to send signals to the various remote parts of her body. For example, to activate her tail became a major tactical problem, for any signal originating in her distant head required some time to reach the effective muscles of the tail. It was the same with the ponderous legs; they could not be called into instant action.

Her brain was too small and too undifferentiated to permit reasoning or memory; habit ingrained warned her of danger, and only the instinctive use of her tail protected her from the kind of assault she had just experienced. As for explaining in specific terms the gnawing agitation she now felt, and which had been the major reason for her leaving the safety of the herd, her small brain could give her no help.

She therefore walked with splashing grace toward a spot some distance upstream. How beautiful she was as she moved through the growing darkness! All parts of her great body seemed to relate to one central impulse, gently twisting neck, stalwart central structure, slow-moving mighty legs, and delicate tail extending almost endlessly behind and balancing the whole. It would require far more than a hundred million years of experiment before her equal would be seen again.

She was moving toward a white chalk cliff which she had known before. It stood some distance in from the lagoon, sixty feet higher than the river at its feet. Here, back eddies had formed a swamp, and as she approached this protected area, diplodocus became aware of a sense of security. She hunched her shoulders again and adjusted her hips. Moving her long tail in graceful arcs, she tested the edge of the swamp with one massive forefoot. Liking what she felt, she moved slowly forward, sinking deeper and deeper into the dark waters until she was totally submerged, except for the knobby tip of her head which she left exposed so that she could breathe.

She did not fall asleep, as she should have done. The gnawing insatiety kept her awake, even though she could feel the new stone working on the foliage she had consumed that day and even though the buzzing of the day insects had ceased, indicating that night was at hand. She wanted to sleep but could not, so after some hours the tiny brain sent signals along the extended nerve systems and she pulled herself through the swamp with noisy sucking sounds. Soon she was back in the main channel, still hunting vaguely for something she could neither define nor locate. And so she spent the long tropical night.

Diplodocus was able to function as capably as she did for three reasons. When she was in the swamp at the foot of the cliff, an area that would have meant death for most animals, she was able to extricate herself because her massive feet had a curious property; although they made a footprint many inches across as they flattened out in mud, they could, when it came time to withdraw them from the clinging muck, compress to the width of the foreleg, so that for diplodocus to pull her huge leg and foot from mud was as simple as pulling a reed from the muck at the edge of the swamp; there was nothing for the mud to cling to, and the leg pulled free with a swooshing sound.

Diplodocus, “double beams,” was so named because sixteen of her tail vertebrae—twelve through twenty-seven behind the hips—were made with paired flanges to protect the great artery that ran along the underside of the tail. But the vertebrae had another channel topside, and it ran from the base of the head to the strongest segment of the tail. In this channel lay a powerful and very thick sinew which was anchored securely at shoulder and hip and which could be activated from either position. Thus the long neck and the sweeping tail were the progenitors of the crane, which in later time would lift extremely heavy objects by the clever device of running a cable over a pulley and counterbalancing the whole. The pulley used by diplodocus was the channel made by the paired flanges of the vertebrae; her cable was the powerful sinew of neck and tail; her counterbalance was the bulk of her torso, and all functioned with an almost divine simplicity. Had she had powerful teeth, her neck was so excellently balanced that she could have lifted into the air the dinosaur that attacked her in the way the claw of a well-designed crane can lift an object many times its own apparent weight. Without this advanced system of cable and pulley, diplodocus could have activated neither her neck nor her tail, and she could not have survived. With it, she was a sophisticated machine, as well adapted to her mode of life as any animal which might succeed her in generations to come.

The third advantage she had was remarkable, and raises questions as to how it could have developed. The powerful bones of her legs, which were under water most of the time, were of the most heavy construction, thus providing her with necessary ballast, but those that were higher in her body were of successively lighter bulk, not only in sheer weight but also in actual bone composition, and this delicate construction buoyed up her body, permitting it almost to float.

That was not all. Many fenestrations, open spaces like windows, perforated the vertebrae of her neck and tail, thus reducing their weight. These intricate bones, with their channels top and bottom, were so exquisitely engineered that they can be compared only to the arches and windows of a Gothic cathedral. Bone was used only where it was required to handle stress. No shred was left behind to add its weight if it could be dispensed with, yet every arch required for stability was in place. The joints were articulated so perfectly that the long neck could twist in any direction, yet the flanges within which the sinews rode were so strong that they would not be damaged if a great burden was placed on neck or head.

It was this marvel of engineering, this infinitely sophisticated machine which had only recently developed and which would flourish for another seventy million years, that floated along the shore of the lagoon that night, and when the little mammal came out of its nest at dawn, it saw her twisting her neck out toward the lagoon, then inland toward the chalk cliff.

Finally she turned and swam back toward the swamp at the foot of the cliff. When she reached there she sniffed the air in all directions, and one smell seemed familiar, for she turned purposefully toward fern trees at the far end of the swamp, and from them appeared the male diplodocus for which she had been searching. They approached each other slowly, poling themselves along the bottom of the swamp, and when they met they rubbed necks together.

She came close to him, and the little mammal watched as the two giant creatures coupled in the water, their massive bodies intertwined in unbelievable complexity. When he rutted he simply climbed on the back of his mate, locking his forepaws about her, and concluded his mating in seven seconds. The two reptiles remained locked together most of the forenoon.

When they were finished they separated and each by his own route swam away to join the herd. It consisted of fifteen members of the diplodocus family, three large males, seven females and five young animals. They moved together, keeping to the deep water most of the time but never loath to come into the river for food. In the water they poled themselves along with their feet barely touching bottom, their long tails trailing behind, and all kept in balance by that subtle arrangement of bone whereby the heaviest hung close to the bottom, allowing the lighter to float on top.

The family did not engage in play such as later animals of a different breed would; they were reptiles and as such were sluggish. Since they had cold blood with an extremely slow metabolism, they needed neither exercise nor an abundance of food; a little motion sufficed them for a day, a little food for a week. They often lay immobile for hours at a time, and their tiny brains spurred them to action only when they faced specific problems.

After a long time she felt another urge, positively irresistible, and she moved along the shore to a sandy stretch of beach not far from the chalk cliff. There she swept her tail back and forth, clearing a space, in the middle of which she burrowed both her snout and her awkward forelegs. When a declivity was formed, she settled herself into it and over a period of nine days deposited thirty-seven large eggs, each with a protective leathery shell.

When her mission ashore was accomplished, she spent considerable time brushing sand over the nest with her tail and placing with her mouth bits of wood and fallen leaves over the spot so as to hide it from animals that might disturb the eggs. Then she lumbered back to the lagoon, soon forgetting even where she had laid the eggs. Her work was done. If the eggs produced young reptiles, fine. If not, she would not even be aware of their absence.

It was this moment that the furry animal had been watching for. As soon as diplodocus submerged herself in the lagoon, he darted forth, inspected the nest, and found one egg that had not been properly buried. It was larger than he, but he knew that it contained food enough for a long time. Experience had taught him that his feast would be tastier if he waited some days for the contents to harden, so this time he merely inspected his future banquet, and kicked a little dirt over it so that no one else might spot it.

After the thirty-seven eggs had baked four days in the hot sand, he returned with three mates, and they began attacking the egg, gnawing with incisors at its hard shell. They had no success, but in their work they did uncover the egg even more.

At this point a dinosaur much smaller than any which had appeared previously, but at the same time much larger than the mammals, spotted the egg, knocked off one end and ate the contents. The pantotheres were not sorry to see this, for they knew that much meat would still be left in the remnants, so when the small dinosaur left the area, they scurried in to find that the broken eggshells did yield a feast.

In time the other eggs, incubated solely by action of the sun, hatched, and thirty-six baby reptiles sniffed the air, knew by instinct where the lagoon lay, and in single file, they started for the safety of the water.

Their column had progressed only a few yards when the flying reptile that had tried to snatch the mammal spotted them and with expert glide swooped down, catching one in its beak, taking it to its hungry young. Three more trips the reptile made, catching an infant diplodocus each time.

Now the small dinosaur that had eaten the egg also saw the column, and he hurried in to feed on six of the young. As he did so, the others scattered, but with an instinct that kept them moving always closer to the lagoon. The original thirty-seven were now down to twenty-six, and these were attacked continuously by the rapacious flier and the carnivorous dinosaur. Twelve of the reptiles finally reached the water, but as they escaped into it a large fish with bony head and jagged rows of teeth ate seven of them. On the way, another fish saw them swimming overhead and ate one, so that from the original thirty-seven eggs, there were now only four possible survivors. These, with sure instinct, swam on to join the family of fifteen grown diplodocuses, which had no way of knowing the young reptiles were coming.

As the little ones grew, diplodocus herself had no way of knowing that they were her children. They were merely reptile members that had joined the family, and she shared with other members of the herd the burden of teaching them the tricks of life.

When the young were partly grown, their thin snakelike bodies increasing immensely, diplodocus decided that it was time to show them the river. Accompanied by one of the adult males, she set out with the four youngsters.

They had been in the river only a short time when the male snorted sharply, made a crackling sound in his throat, and started moving as fast as he could back to the lagoon. Diplodocus looked up in time to see the most terrifying sight the tropical jungle provided. Bearing down upon the group was a monstrous two-legged creature towering eighteen feet high, with huge head, short neck and rows of gleaming teeth.

It was allosaurus, king of the carnivores, with jaws that could bite the neck of diplodocus in half. When the great beast entered the water to attack her, she lashed at him with her tail and knocked him slightly off course. Even so, the monstrous six-inch claws on his prehensile front feet raked her right flank, laying it open.

He stumbled, righted himself and prepared a second attack, but again she swung her heavy tail at him, knocking him to one side. For a moment it looked as if he might fall, but then he recovered, left the river and rushed off in a new direction. This put him directly behind the male diplodocus, and even though the latter was retreating as fast as possible toward the lagoon, the momentum of allosaurus was such that he was able to reach forward and grab him where the neck joined the torso. With one terrifying snap of the jaws, allosaurus bit through the neck, vertebrae and all, and brought his victim staggering to his knees. The long tail flashed, but to no avail. The body twisted in a violent effort to free itself of the daggerlike teeth, but without success.

With great pressure, allosaurus pushed the giant reptile to the ground, then, without relinquishing its bloody hold, began twisting and tearing at the flesh until the mighty teeth joined and a large chunk of meat was torn loose. Only then did allosaurus back away from the body. Thrusting its chin in the air, it adjusted the chunk of meat in its mouth and dislocated its jaw in such a way that the huge morsel could slide down into the gullet, from whence it would move to the stomach, to be digested later. Twice more it tore at the body, dislodging great hunks of meat which it eased down its throat. It then stood beside the fallen body for a long time as if pondering what to do. Crocodiles approached for their share, but allosaurus drove them off. Carrion reptiles flew in, attracted by the pungent smell of blood, but they too were repulsed.

As allosaurus stood there defying lagoon and jungle alike, he represented an amazing development, as intricately devised as diplodocus. His jaws were enormous, their rear ends lashed down by muscles six inches thick and so powerful that when they contracted in opposing directions they exerted a force that could bite through trees. The edges of the teeth were beautifully serrated, so they could cut or saw or tear; sophisticated machines a hundred and forty million years later would mimic their principle.

The teeth were unique in another respect. In the jaw of allosaurus, imbedded in bone beneath the tooth sockets, lay seven sets of replacements for each tooth. If, in biting through the neck bones of an adversary, allosaurus lost a tooth, this was of little concern. Soon a replacement would emerge, and behind it six others would remain in line waiting to be called upon, and if they were used up, others would take place in line, deep within the jawbone.

Now allosaurus lashed his short tail and emitted growls of protest. He had killed this vast amount of food but could not consume it. Other predators appeared, including the two smaller dinosaurs that had visited the beach before. All remained at a safe distance from allosaurus.

He took one more massive bite from the dead body but could not swallow it. He spit it out, glared at his audience, then tried again. Covered with sand, the flesh rested in his gaping mouth for several minutes, then slid down the extended neck. With a combative awk-awk from deep within his throat, allosaurus lunged ineffectively at the watchers, then ambled insolently off to higher ground.

As soon as he was gone, the scavengers moved in—reptiles from the sky, crocodiles from the lagoon, two kinds of dinosaurs from land and the unnoticed mammals from the roots of the ginkgo tree. By nightfall the dead diplodocus, all thirty-three tons of him, had disappeared and only his massive skeleton lay on the beach.

Wounded diplodocus and the four young dinosaurs that had witnessed this massacre now swam back to the lagoon. In the days that followed, she began to experience the last inchoate urge she would ever know. Sharp pains radiated slowly from the place where allosaurus had ripped her. She found no pleasure in association with the other members of the herd. She was drawn by some inexplicable force back to the swamp at the chalk cliff, not for purposes of recreating the family of which she was a part but for some pressing reason she had never felt before.

For nine days she delayed heading for the swamp, satisfying herself with half-sleep in the lagoon, poling herself idly half-submerged from one warm spot to another, but the pain did not diminish. Vaguely she wanted to float motionless in the sun, but she knew that if she did this, the sun would destroy her. She was a reptile and had no means of controlling body heat; to lie exposed in the sun long enough would boil her to death in her own internal liquids.

Finally, on the tenth day she entered the river for the last time, stepping quietly like some gracious queen. She stopped occasionally to browse on some tree, lifting her head in a glorious arc on which the late sun shone. Her tail extended behind, and when she switched it for some idle purpose it gleamed like a scimitar set with jewels.

How beautiful she was as she took that painful journey, how gracefully coordinated her movements as she swam toward the chalk cliff. She moved as if she owned the earth and conferred grace upon it. She was the great final sum of millions of years of development. Slowly, swaying from side to side with majestic delicacy, she made her way to the swamp that lay at the foot of the cliff.

There she hesitated, twisting her great neck for the last time as if to survey her kingdom. Thirty feet above the earth her small head towered in one last thrust. Then slowly it lowered; slowly the graceful arc capsized. The tail dragged in the mud and the massive knees began to buckle. With a final surge of determination, she moved herself ponderously and without grace into a deep eddy.

Its murky waters crept up her legs, which would never again be pulled forth like reeds; this was the ultimate capture. The torn side went under; the tail submerged for the last time, and finally even the lovely arc of her neck disappeared. The knobby protuberance holding her nose stayed aloft for a few minutes, as if she desired one last lungful of the heavy tropical air, then it too disappeared. She had gone to rest, her mighty frame imprisoned in the muck that would embrace her tightly for a hundred and thirty-six million years.

It was ironic that the only witness to the death of diplodocus was the little pantothere that watched from the safety of a cycad tree, for of all creatures who had appeared on the beach, he was the only one that was not a reptile. The dinosaurs were destined to disappear from earth, while this little animal would survive, its descendants and collaterals populating the entire world, first with prehistoric mammals themselves destined to extinction—titanotheres, mastodons, eohippus—and subsequently with animals man would know, such as the mammoth, the lion, the elephant, the bison and the horse.

Of course, certain smaller reptiles such as the crocodile, the turtle and the snake would survive, but why did they and the little mammal live when the great reptiles vanished? This remains one of the world’s supreme mysteries. About sixty-five million years ago, as the New Rockies were emerging, the dinosaurs and all their immediate relations died out. The erasure was total, and scholars have not yet agreed upon a satisfactory explanation. All we know for sure is that these towering beasts disappeared. Triceratops with its ruffed collar, tyrannosaurus of the fearful teeth, ankylosaurus the plated ambulating tank, trachodon the gentle duck-billed monster—all had vanished.

Ingenious theories have been advanced, some of them captivating in their imaginativeness, but they remain only guesses. Yet because the mystery is so complete, and so relevant to man, all proposals merit examination. They fall into three major groups.

The first relates to the physical world, and each argument has some merit. Since the death of the dinosaurs coincided with the birth of the New Rockies, there may have been a causal relationship, with the vast lowland swamps disappearing. Or temperatures may have risen to a degree that killed off the great beasts. Or plant life may have altered so rapidly that the dinosaurs starved. Or the disappearance of the extensive inland sea changed water relationships and dried up lagoons. Or mountain building somehow involved loss of oxygen. Or a combination of changes in plant food doomed the reptiles. Or a single catastrophic sun flare burned the dinosaurs to death, while the mammals, with their built-in heat-adjusting apparatus, survived.

The second theory is more difficult to assess, because it deals with psychological factors, which, even though they may be close to the truth, are so esoteric that they cannot be quantitatively evaluated. Classes of animals, like men, empires and ideas, have a predestined length of life, after which they become senescent and die out. Or the dinosaurs had overspecialized and could not adapt to changes in environment. Or they became too large and fell of their own weight. Or they reproduced too slowly. Or their eggs became infertile. Or carnivores ate the vegetarian dinosaurs faster than they could reproduce and then starved for lack of food. Or for some unknown reason they lost their vital drive and became indifferent to all problems of survival.

The third combines all the reasons that relate to warfare between a declining reptilian world and a rising mammalian one. Mammals ate the eggs of the dinosaurs at such a rate that the reptiles could not keep producing enough to ensure survival. Or mammals of increasing size killed off the smaller reptiles and ate them. Or mammals preempted feeding grounds. Or mammals, because of their warm blood and smaller size, could adjust more easily to the changes introduced by the mountain building or other environmental shifts. Or a world-wide plague erupted to which the reptiles were subject while the mammals were not.

For each of these theories there are obvious refutations, and scholars have expounded them. But if we reject these proposals, where does that leave us in our attempt to find out why this notable breed of animal vanished? We must know, lest the day come when we repeat their mistakes and doom ourselves to extinction.

The best that can be said is that an intricate interrelationship of changes occurred, involving various aspects of life, and that the great reptiles failed to accommodate to them. All we know for sure is that in rocks from all parts of the world there is a lower layer dating back seventy million years in which one finds copious selections of dinosaur bones. Above it there is an ominous layer many feet thick in which few bones of any kind are found. And above that comes a new layer often crowded with the bones of mammal predecessors of the elephant, the camel, the bison and the horse. The dead reach of relatively barren rock, representing the death of the dinosaurs, has not yet been explained.

Long after they disappeared, and after man had risen to the point where he could search out the fossilized skeletons of the dinosaurs, it would become fashionable to make fun of the great reptiles which had vanished through some folly of their own. The lumbering beasts would be held up to ridicule as failures, as inventions that hadn’t worked, as proof that a small brain in a big body makes survival impossible.

Facts prove just the opposite. The giant reptiles dominated the earth for one hundred and thirty-five million years; man has survived only two million and most of that time in mean condition. Dinosaurs were some sixty-seven times as persistent as man has so far been. They remain one of the most successful animal inventions nature has provided. They adjusted to their world in marvelous ways and developed all the mechanisms required for the kind of life they led. They are honored as one of the world’s longest-lived species, and they dominated their vast period of time just as man dominates his relatively brief one.

Fifty-three million years ago, while the New Rockies were still developing and long after diplodocus had vanished, in the plains area, where the twin pillars formed, an animal began to develop which in later times would give man his greatest assistance, pleasure and mobility. The progenitor of this invaluable beast was a curious little creature, a four-legged mammal, for the age of reptiles was past, and he stood only seven or eight inches high at the shoulder. He weighed little, had a body covering of part-fur, part-hair and seemed destined to develop into nothing more than a small inconsequential beast.

He had, however, three characteristics which would determine his future potential. The bones in his four short legs were complete and separate and capable of elongation. On each foot he had five small toes, that mysteriously perfect number which had characterized most of the ancient animals, including the great dinosaurs. And he had forty-four teeth, arranged in an unprecedented manner: in front, some peglike teeth as weak as those of diplodocus; then a conspicuous open space; then at the back of the jaw, numerous grinding molars.

This little animal made no impression on his age, for he was surrounded by other much larger mammals destined for careers as rhinoceroses, camels and sloths. He lived carefully in the shady parts of such woods as had developed and fed himself by browsing on leaves and soft marsh plants, for his teeth were not strong and would quickly have worn down had they been required to eat rough food like the grass which was even then beginning to develop.

If one had observed all the mammals of this period and tried to evaluate the chances of each to amount to something, one would not have placed this quiet little creature high on the list of significant progenitors; indeed, it seemed then like an indecisive beast which might develop in a number of different ways, none of them memorable, and it would have occasioned no surprise if the little fellow had survived a few million years and then quietly vanished. Its chances were not good.

The curious thing about this little forerunner of greatness is that although we are sure that he existed and are intellectually convinced that he had to have certain characteristics, no man has ever seen a shred of physical evidence that he really did exist. No fossil bone of this little creature has so far been found; we have tons of bones of diplodocus and her fellow reptiles, all of whom vanished, but of this small prototype of one of the great animal families, we have no memorials whatever. Indeed, he has not yet even been named, although we are quite familiar with his attributes; perhaps when his bones are ultimately found—and they will be—a proper name would be “paleohippus,” the hippus of the Paleocene epoch. When word of his discovery is flashed around the world, scholars and laymen in all countries will be delighted, for they will have come into contact with the father of a most distinguished race, one which all men have loved and from which most have profited.

Perhaps thirteen million years after “paleohippus” flourished, and when the land that would contain the twin pillars had begun to form, the second in line and first-known in this animal family appeared and became so numerous that in the land about the future pillars hundreds of skeletons would ultimately be laid down in rock, so that scientists would know this small creature as familiarly as they know their own puppies.

He was eohippus, an attractive small animal about twelve inches high at the shoulder. He looked more like a friendly dog than anything else, with small alert ears, a swishing tail to keep insects away, a furry kind of coat and a longish face, which was needed to accommodate the forty-four teeth, which persisted. The teeth were still weak, so that the little creature had to content himself with leaves and other soft foods.

But the thing that marked eohippus and made one suspect that this family of animals might be headed in some important direction was the feet. On the short front feet, not yet adapted for swift movement, the five original toes had been reduced to four; one had only recently disappeared, the bones which had once sustained it vanishing into the leg. And on the rear foot there were now three toes, the two others having withered away during the course of evolution. But the surviving toes had tiny hoofs instead of claws.

One could still not predict what this inconspicuous animal was going to become, and the fact that he would stand second in the sixty-million-year process of creating a noble animal seemed unlikely. Eohippus seemed more suited for a family pet than for an animal of distinction and utility.

And then, about thirty million years ago, when the land that was to form the twin pillars was being laid down, mesohippus developed, twenty-four inches high at the shoulders and with all the basic characteristics of his ancestors, except that he had only three toes on each of his feet. He was a sleek animal, about the size of our collie or red fox. The forty-four teeth kept his face long and lean and his legs were beginning to lengthen, but his feet still contained pads and small hoofs.

Then, about eighteen million years ago, a dramatic development took place which solved the mystery. Merychippus appeared, a most handsome three-toed animal forty inches high, with bristly mane, extended face and protective bars behind the eye sockets.

He had one additional development which would enable the horse family to survive in a changing world: his teeth acquired the remarkable capacity to grow out from the socket as they wore down at the crown. This permitted the proto-horse to quit browsing on such leaves as he found and to move instead to grazing on the new grasses that were developing on the prairies. For grass is a dangerous and difficult food; it contains silica and other roughnesses that wear down teeth, which must do much grinding in order to prepare the grass for digestion. Had not merychippus developed these self-renewing grinders, the horse as we know it could have neither developed nor survived. But with this almost magical equipment, he was prepared.

These profound evolutions occurred on the plains that surrounded the site of the twin pillars. There on flat lands that knew varied climates, from tropical to sub-arctic, depending upon where the equator was located at the time, this singular breed of animal went through the manifold changes that were necessary before it stood forth as an accomplished horse.

One of the biggest changes in the antecedents of the horse appeared about six million years ago, when pliohippus, the latest in the breed, evolved with only one toe on each foot and with the pads on which his ancestors had run eliminated. It now had a single hoof. This animal was a medium-sized beautiful horse in almost every sense of the word, and would have been recognized as such, even from a considerable distance. There would be minor refinements, mostly in the teeth and in the shape of the skull, but the horse of historic times was now foreshadowed.

He arrived as equus about two million years ago, as splendid an animal as the ages were to produce. Starting from the mysterious and unseen “paleohippus,” this breed had unconsciously and with great persistence adapted itself to all the changes that the earth presented, adhering always to those mutations which showed the best chance of future development. “Paleohippus,” of the many capacities, eohippus of the subtle form, merychippus with the horselike appearance, pliohippus with the single hoof—these attributes persisted; there were dozens of other variations equally interesting which died out because they did not contribute to the final form. There were would-be horses of every description, some with the most ingenious novelties, but they did not survive, for they failed to adjust to the earth as it was developing; they vanished because they were not needed. But the horse, with its notable collection of virtues and adjustments, did survive.

About one million years ago, when the twin pillars were well formed, a male horse with chestnut coloring and flowing tail lived in the area as part of a herd of about ninety. He was three years old and gifted with especially strong legs that enabled him to run more swiftly than most of his fellows. He was a gamin creature and had left his mother sooner than any of the other males of his generation. He was the first to explore new arrivals on the prairie and had developed the bad habit of leading any horses that would follow on excursions into canyons or along extended draws.

One bright summer morning this chestnut was leading a group of six adventurous companions on a short foray from the main herd. He took them across the plains that reached out from the twin pillars and northward into a series of foothills that contained passageways down which they galloped in file, their tails flowing free behind them as they ran. It was an exhilarating chase, and at the end of the main defile they turned eastward toward a plain that opened out invitingly, but as they galloped they saw blocking their way two mammoths of extraordinary size. The great smooth-skinned creatures towered over the horses, for they were gigantic, fourteen feet tall at the shoulders, with monstrous white tusks that curved downward from the head. The tips of the tusks reached sixteen feet, and if they caught an adversary, they could toss him far into the air. The two mammoths were imposing creatures, and had they been ill-disposed toward the horses, could have created havoc, but they were placid by nature, intending no harm.

The chestnut halted his troop, led them at a sober pace around the mammoths, coming very close to the great tusks, then broke into a gallop which would take him onto the eastern plains, where a small herd of camels grazed, bending awkwardly forward. The horses ignored them, for ahead stood a group of antelope as if waiting for a challenge. The seven horses passed at full speed, whereupon the fleet antelope, each with a crown of four large antlers, sprang into action, darting after them.

For a few moments the two groups of animals were locked in an exciting race, the horses a little in the lead, but with a burst of speed the antelopes leaped ahead and before long the horses saw only dust. It had been a joyous race, to no purpose other than the challenge of testing speed.

Beside the grazing area on which the antelope had been feeding there rested a family of armadillos, large ratlike creatures encased in collapsible armor. The horses were vaguely aware of them but remained unconcerned, for the armadillo was a slow, peaceful creature that caused no harm. But now the round little animals stopped searching for slugs and suddenly rolled themselves into a defensive position. Some enemy, unseen to the horses, was approaching from the south and in a moment it appeared, a pack of nine dire wolves, the scourge of the plains, with long fangs and swift legs. They loped easily over the hill that marked the horizon, peering this way and that, sniffing at the air. The wolf serving as scout detected the armadillos and signaled his mates. The predators hurried up, inspected the armor-plated round balls, nudged them with their noses and turned away. No food there.

With some apprehension, the horses watched the nine enemies cross the grassland, hoping that they would pass well to the east, but this was not to be. The lead wolf, a splendid beast with sleek gray coat, spotted the horses and broke into a powerful run, followed instantly by his eight hunting companions. The chestnut snorted and in the flash of a moment realized that he must not lead his six horses back into the canyons from which they had just emerged, for the two mammoths might block the way, allowing the dire wolves to overtake any straggler and cut him down.

So with an adroit leap sideways he broke onto the plains in the direction the antelope had taken and led his troop well away from their home terrain. They galloped with purpose, for although the dire wolves were not yet close at hand, they had anticipated the direction the horses might take and had vectored to the east to cut them off. The chestnut, seeing this maneuver, led his horses to the north, which opened a considerable space between them and the wolves.

As they ran to their own safety, they passed a herd of camels that were slower-moving. The big awkward beasts saw the apprehension of the horses and took fright, although what the cause of the danger was they did not yet know. There was a clutter on the prairie and much dust, and when it had somewhat settled, the horses were well on their way to safety but the camels were left in the direct path of the nine wolves. The lumbering camels ran as fast as they could, scattering to divert attack, but this merely served to identify the slowest-moving and upon this unfortunate the wolves concentrated.

Cutting at him from all sides with fearful teeth, the wolves began to wear him down. He slowed. His head drooped. He had no defense against the dire wolves and within a few moments one had leaped at his exposed throat. Another fastened onto his right flank and a third slashed at his belly. Uttering a futile cry of anguish, the camel collapsed, his ungainly feet buckling under the weight of the wolves. In a flash, all nine were upon him, so that before the horses left the area, the camel had been slain.

At a slow walk they headed south for the hills that separated them from the land of the twin pillars. On the way they passed a giant sloth who stood sniffing at the summer air, dimly aware that wolves were on the prowl. The huge beast, twice the size of the largest horse, knew from the appearance of the horses that they had encountered wolves, and retreated awkwardly to a protected area. An individual sloth, with his powerful foreclaws and hulking weight, was a match for one wolf, but if caught by a pack, he could be torn down, so battle was avoided.

Now the chestnut led his horses into the low hills, down a gully and out onto the home plains. In the distance the twin pillars—white at the bottom where they stood on the prairie, reddish toward the top, and white again where the protecting caps rested—were reassuring, a signal of home, and when all seven of the troop were through the pass, they cantered easily back to the main herd. Their absence had been noted and various older horses came up to nuzzle them. The herd had a nice sense of community, as if all were members of the same family, and each was gratified when others who had been absent returned safely.

Among the six followers accompanying the chestnut on his foray was a young dun-colored mare, and in recent weeks she had been keeping close to him and he to her. They obviously felt an association, a responsibility each to the other, and normally they would by now have bred, but they were inhibited by a peculiar awareness that soon they would be on the move. None of the older animals had signified in any way that the herd was about to depart this congenial land by the twin pillars, but in some strange way the horses knew that they were destined to move … and to the north.

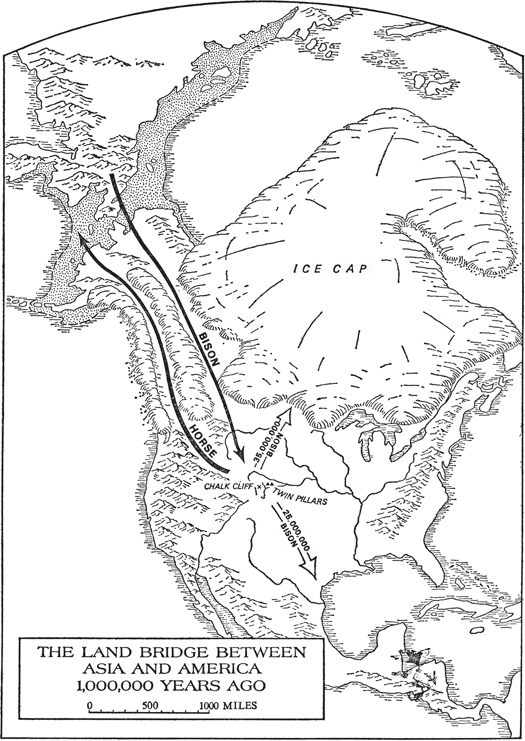

What was about to happen would constitute one of the major mysteries of the animal world. The horse, that splendid creature which had developed here at twin pillars, would desert his ancestral home and emigrate to Asia, where he would prosper, and the congenial plains at the pillars would be occupied by other animals. Then, about four hundred thousand years later, the horse would return from Asia to reclaim the pastures along the river, but by the year 6000 B.C. he would become extinct in the Western Hemisphere.

The horses were about to move north and they knew they could not accommodate a lot of colts, so the chestnut and the mare held back, but one cold morning, when they had been chasing idly over the plains as if daring the dire wolves to attack them, they found themselves alone at the mouth of a canyon where the sun shone brightly, and he mounted her and in due course she produced a handsome colt.

It was then that the herd started its slow movement to the northwest. Three times the chestnut tried unsuccessfully to halt them so that the colt could rest and have a fighting chance of keeping up. But some deep instinctive drive within the herd kept luring them away from their homeland, and soon it lay far behind them. The dun-colored mare did her best to keep the colt beside her, and he ran with ungainly legs to stay close. She was pleased to see that he grew stronger each day and that his legs functioned better as they moved onto higher ground.

But in the fifth week, as they approached a cold part of their journey, food became scarce and the wisdom of this trek, doubtful. Then the herd had to scatter to find forage, and one evening as the chestnut and the mare and their colt nosed among the scrub for signs of grass, a group of dire wolves struck at them. The mare intuitively presented herself to the wolves in an effort to protect her colt, but the fierce gray beasts were not deluded by this trick, and cut behind her and made savage lunges at it. This enraged the chestnut, who sprang at the wolves with flashing hoofs, but to no avail. Mercilessly, the wolves cut down the colt. His piteous cries sounded for a moment, then died in harrowing gurgle as his own blood drowned him.

The mare was distraught and tried to attack the wolves, but six of them detached themselves and formed a pack to destroy her. She defended herself valiantly for some moments while her mate battled with the other wolves at the body of the colt. Then one bold wolf caught her by a hamstring and brought her down. In a moment the others were upon her, tearing her to pieces.

The whole group of wolves now turned their attention to the chestnut, but he broke loose from them and started at a mad gallop back toward where the main herd of horses had been. The wolves followed him for a few miles, then gave up the chase and returned to their feast.

Mammals, unlike reptiles, had some capacity for memory, and as the trek to the northwest continued, the chestnut felt sorrow at the loss of his mate and the colt, but the recollection did not last long, and he was soon preoccupied with the problems of the journey.

It was a strange hegira on which the horses of Centennial were engaged. It would take them across thousands of miles and onto land that had been under water only a few centuries earlier. For this was the age of ice. From the north pole to Pennsylvania and Wisconsin and Wyoming vast glaciers crept, erasing whatever vegetation had developed there and carving the landscape into new designs.

At no point on earth were the changes more dramatic than at the Bering Sea, that body of ice-cold water which separates Asia from America. The great glaciers used up so much ocean water that the level of this sea dropped three hundred feet. This eliminated the Bering Sea altogether, and in its place appeared a massive land bridge more than a thousand miles wide. It was an isthmus, really, joining two continents, and now any animal that wished, or man, too, when he came along, could walk with security from Asia to America—or the other way.

The bridge, it must be understood, was not constructed along that slim chain of islands which now reaches from America to Asia. Not at all. The drop of ocean was so spectacular that it was the main body of Asia that was joined substantially to America; the bridge was wider than the entire compass of Alaska.

It was toward the direction of this great bridge, barely existent when the true horse emerged, that the chestnut now headed. In time, as older horses died off, he became acknowledged leader of the herd, the one who trotted at the head on leisurely marches to new meadows, the one who marshaled the herd together when danger threatened. He grew canny in the arts of leadership, homing on the good pastures, seeking out the protected resting places.

As the horses marched to the new bridge in the northwest, to their right in unending progression lay the snouts of the glaciers, now a mile away, later on, a hundred miles distant, but always pressing southward and commandeering meadowlands where horses had previously grazed. Perhaps it was this inexorable pressure of ice from the north, eating up all good land, that had started the horses on their emigration; certainly it was a reminder that food was getting scarce throughout their known world.

One year, as the herd moved ever closer to the beginning of the bridge, the horses were competing for food with a large herd of camels that were also deserting the land where they had originated. The chestnut, now a mature horse, led his charges well to the north, right into the face of the glacier. It was the warm period of the year and the nose of the glacier was dripping, so that the horses had much good water and there was, as he had expected, good green grass.

But as they grazed, idling the summer away before they returned to the shoreline, where they would be once more in competition with the camels, he happened to peer into a small canyon that had formed in the ice, and with four companions he penetrated it, finding to his pleasure that it contained much sweet grass. They were grazing with no apprehension when suddenly he looked up to see before him a most gigantic mammoth. It was as tall as three horses, and its mighty tusks were like none he had seen at the pillars. These tusks did not stretch forward, but turned parallel to the face in immense sweeping circles that met before the eyes.

The chestnut stood for a moment surveying the huge beast. He was not afraid, for mammoths did not attack horses, and even if for some unfathomable reason this one did, the chestnut could easily escape. And then slowly, as if the idea were incomprehensible, the stallion began to realize that under no circumstances could this particular mammoth charge, for it was dead. Its frozen rear quarters were caught in the icy grip of the glacier; its front half, from which the glacier had melted, seemed alive. It was a beast in suspension. It was there, with all its features locked in ice, but at the same time it was not there.

Perplexed, the chestnut whinnied and his companions ambled up. They looked at the imprisoned beast, expecting it to charge, and only belatedly did each discover for himself that for some reason he could not explain, this mammoth was immobilized. One of the younger horses probed with his muzzle, but the silent mammoth gave no response. The young horse became angry and nudged the huge beast, again with no results. The horse started to whinny; then they all realized that this great beast was dead. Like all horses, they were appalled by death and silently withdrew.

The chestnut alone wanted to investigate this mystery, and in succeeding days he returned timorously to the small canyon, still puzzled, still captivated by a situation that could not be understood. In the end he knew nothing, so he kicked his heels at the silent mammoth, returned to the grassy area, and led his herd back toward the main road to Asia.

It must not be imagined that the horses emigrated to Asia in any steady progression. The distance from the twin pillars to Siberia was only 3500 miles, and since a horse could cover twenty-five miles a day, the trip might conceivably have been completed in less than a year, but it did not work that way. The horses never chose their direction; they merely sought easier pasturage and sometimes a herd would languish in one favorable spot for eight or nine years. They were pulled slowly westward by mysterious forces, and no horse that started from the twin pillars ever got close to Asia.

But drift was implacable, and the chestnut spent his years from three to sixteen in this overpowering journey, always tending toward the northwest, for the time of the horse in America was ended.

They spent four years on the approaches to Alaska, and now the chestnut had to extend himself to keep pace with the younger horses. Often he fell behind, but he knew no fear, confident that an extra burst of effort would enable him to regain the herd. He watched as younger horses took the lead, giving the signals for marching and halting. The grass seemed thinner this year, and more difficult to find.

One day, late in the afternoon, he was foraging in sparse lands when he became aware that the main herd—indeed the whole herd—had moved on well beyond him. He raised his head with some difficulty, for his breathing had grown tighter, to see that a pack of dire wolves had interposed itself between him and the herd. He looked about quickly for an alternate route, but those available would lead him farther from the other horses; he knew he could outrun the wolves, but he did not wish to increase the distance between himself and the herd.

He therefore made a daring, zigzag dash right through the wolves and toward the other horses. He kicked his heels and with surprising speed negotiated a good two-thirds of the distance through the snarling wolves. Twice he heard jaws snapping at his forelocks, but he managed to kick free.

Then, with terrible suddenness, his breath came short and a great pain clutched at his chest. He fought against it, kept pumping his legs. He felt his body stopping almost in midflight, stopping while the wolves closed in to grab his legs. He felt a sharp pain radiating from his hind quarters where two wolves had fastened onto him, but this external wolf-pain was of lesser consequence than the interior horse-pain that clutched at him. If only his breath could be maintained, he could throw off the wolves. He had done so before. But now the greater pain assailed him and he sank slowly to earth as the pack fell upon him.

The last thing he saw was the uncomprehending herd, following younger leaders, as it maintained its glacial course toward Asia.

Why did this stallion that had prospered so in Colorado desert his amiable homeland for Siberia? We do not know. Why did the finest animal America developed become discontented with the land of his origin? There is no answer. We know that when the horse negotiated the land bridge, which he did with apparent ease and in considerable numbers, he found on the other end an opportunity for varied development that is one of the bright aspects of animal history. He wandered into France and became the mighty Percheron, and into Arabia, where he developed into a lovely poem of a horse, and into Africa, where he became the brilliant zebra, and into Scotland, where he bred selectively to form the massive Clydesdale. He would also journey into Spain, where his very name would become the designation for a gentleman, a caballero, a man of the horse. There he would flourish mightily and serve the armies that would conquer much of the known world, and in 1519 he would leave Spain in small, adventurous ships of conquest and land in Mexico, where he would thrive and develop special characteristics fitting him for life on upland plains. In 1543 he would accompany Coronado on his quest for the golden cities of Quivira, and from later groups of horses brought by other Spaniards some would be stolen by Indians and a few would escape to become feral, once domesticated but now reverted to wildness. And from these varied sources would breed the animals that would return late in history, in the year 1768, to Colorado, the land from which they had sprung, making it for a few brief years the kingdom of the horse, the memorable epitome of all that was best in the relationship of horse and man.

It would be dramatic if we could claim that as the horse left America he met on the bridge to Asia a shaggy, lumbering beast that was leaving Asia to take up his new home in America, but that probably did not happen. The main body of horses deserted America about one million years ago, whereas the ponderous newcomers did not cross the bridge which the horses had used—for it closed shortly after they passed—but a later bridge which opened at the same place and for the same reasons about eight hundred thousand years later.

The beast which came eastward out of Asia had developed late in biologic time, less than two million years ago, but it developed in startling ways. It was a huge and shaggy creature, standing very high at the shoulder and with enormous horns that curved outward, then forward from a bulky forehead that seemed made of rock. When the animal put its head down and walked resolutely into a tree, the tree usually toppled. This ponderous head, held low because of a specialized thick neck, was covered with long, matted hair which itself took up much of the shock when the beast used its head as a battering ram. Males also grew a long, stiff beard, so that their appearance at times seemed satanic. The other major characteristic was that the weight of the animal was concentrated in the massive forequarters, topped by a sizable hump, while the hindquarters seemed unusually slender for so large a beast. The animal, as it had developed in Asia, was so powerful that it had, as an adult, no enemies. Wolves tried constantly to pick off newborn calves or superannuated stragglers, but they avoided mature animals in a group.

This was the ancestral bison, and the relatively few who made the hazardous trip from Asia flourished in their new habitat, and one small herd made its way to the land about the twin pillars, where they found themselves a good home with plenty of grass and security. They multiplied and lived contented lives to the age of thirty, but their size was so gigantic and their heavy horns so burdensome that after only forty thousand years of existence in America, during which time they left their bones and great horns in numerous deposits, so that we know precisely how they looked, the breed exhausted itself.

The original bison was one of the most impressive creatures ever to occupy the land at twin pillars. He was equal in majesty to the mammoth, but like him, was unable to adjust to changing conditions, so like the mammoth, he perished.

That might have been the end of the bison in America, as it was the end of the mammoth and the mastodon and smilodon, the saber-toothed cat, and the huge ground sloth, except that at about the time the original bison vanished, a much smaller and better-adapted version developed in Asia and made its own long trek across a new bridge into America. This seems to have occurred some time just prior to 6000 B.C., and since in the span of geologic time that was merely yesterday, of this fine new beast we have much historic evidence. Bison, as we know them, were established in America and one herd of considerable size located in the area of the twin pillars.

It was late winter when a seven-year-old male of this herd shook the ice off his beard, hunched his awkward shoulders forward as if preparing for some unusual action, and tossed his head belligerently, throwing his rufous mane first over his eyes and then away to one side. He then braced himself as if the anticipated battle were at hand, but when no opponent appeared, he quit his performance and went about the job of pawing at the snow to uncover grass that lay succulent and sweet below.

He stood out among the herd not only for his splendid bulk but also for his coloring, which was noticeably lighter than that of his fellows. He comported himself not with dignity, for he was not an old bull, but with a certain violent willingness; he was what might be called a voluntary animal, eager for whatever change or accident might befall.

For reasons which he could not clearly understand but which were associated somehow with the approach of spring, he started on this wintry day to study carefully the other bulls, and when occasion permitted, to test his strength against theirs. The two- and three-year-olds he dismissed. If they became testy, which they sometimes did, a sharp blow from the flat of his horn disciplined them. The four- and five-year-olds? He had to be watchful with them. Some were putting on substantial weight and were learning to use their horns well. He had allowed one of them to butt heads with him, and he could feel the younger bull’s amazing power, not yet sufficient to issue a serious challenge but strong enough to upset any adversary that was not attentive.

There were also the superannuated bulls, pitiful cases, bulls that had once commanded the herd. They had lost their power either to fight or to command and dragged along as stragglers with the herd, animals of no consequence. They grazed about the edges and occasionally, when fighting loomed, they might charge in with ancient valor, but if a six-year-old interposed himself, they made a few futile gestures and retreated. In earlier years they had suffered broken bones and shattered horn tips and some of them limped and others could see from only one eye. Some of them had even been attacked by wolves, if the wolves caught them alone, and it was not uncommon to see some old bull with flesh wounds along his flanks, filled with flies and itching pain.

The old bulls could be ignored. They were tolerated, and on some long march they would fall behind and fail to climb a hill and the wolves would close in and they would be seen no more.

It was the bulls nine and ten years old that caused perplexity, and these Rufous studied meticulously. He was not at all confident that he could handle them. There was one with a slanting left horn; he had dominated the herd three years ago, and even last year had been a bull to conjure with, for he had massive shoulders which could dislodge an opponent and send him sprawling. There was the brown bull with the heavy hair over his eyes; he had been a champion of several springs and had only a few days ago given Rufous a sharp buffeting. Particularly there was the large black bull that had dominated last spring; he seemed quite unassailable and aware that the others held him in awe. Twice in recent weeks Rufous had bumped against him, as if by accident, and the black bull had known what was happening and had casually swung his head around and knocked Rufous backward; this black bull had tremendous power and the skill to use it.

As spring approached and the snows melted, disclosing a short, rich grass refreshed by moisture, the herd began to mill about as if it wished to move to other ground, and one morning as Rufous was grazing in the soft land between the twin pillars, with the warm sun of spring on his back, one of the cows started nudging her way among the other cows and butting the older bulls. This was the cow that made important decisions for the herd, for although the commanding bull disciplined the herd and stood ready to fight any member at any time, he did not direct them as to where they should move or when. It was as if the lead bull were the general in battle, the lead cow the prime minister in running the nation.

She now decided that it was time for her herd to move northward, and after butting others of her followers, she set out at a determined pace, leaving the twin pillars behind. She headed for a pass through the low chalk hills to the north, then led her charges up a draw to the tableland beyond. There she kept the herd for several days, after which she led them slowly and with no apparent purpose to the river that defined this plateau to the north. Testing the water at several places, she decided which crossing was safest and plunged in.

The water was icy cold from melting snow, but she kicked her legs vigorously, swimming comfortably with the current and climbing out at last to shake her matted hair, sending showers of spray into the sunlight. From the north bank she watched with a leader’s care as older cows nudged yearlings into the river, then swam beside them, keeping the younger animals upstream, so that if the current did overcome them, they would bounce against their mothers and thus gain security for the next effort.

When the main body of the herd was safely across, the old bulls grudgingly and sometimes with growls of protest entered the river, swimming with powerful kicks as the water threw their beards into their faces. When they climbed onto the north bank they shook themselves with such fury that they produced small rainstorms.

Rufous was one of the last to cross, and he did so carefully, as if studying this particular crossing against the day when he might have to use it in some emergency. He did not like the footing on the south bank, but once the lead cow was satisfied that the cows and calves were safely across, she ignored whatever bulls were left behind and set out purposefully for the grazing lands to which she was leading her herd.

When she reached this spot, less than a hundred miles from the twin pillars, she stopped, smelled the ground to assure herself that it was good, then turned the leadership of the herd back to the bulls, assuming once more the passive role of merely another cow. But if any decision of moment were required, she would again step forth and assert herself, and when she grew too old to assume this task the responsibility would pass to some other strongly opinionated cow, for the leadership of a large group was too important to be left to males.

It was now spring and the calving season was at hand. The sun would rise, as on a normal day, but some cow would experience a profound urge to be by herself, and she would move with determination toward some unknown objective, and if any other cow, or even a bull, tried to interpose, she would knock the offender aside and pursue her course. She would seek some secluded area, even if it were only behind the brow of a low hill, and there she would lie on the ground and prepare for the birth of her calf.

This year a small black cow left the herd as soon as the new grounds were reached, for her time was at hand. As she passed two old bulls they nuzzled her as if to ask what she was about, but she repelled them brusquely and sought a spot not far from the river where trees gave her some protection. There she gave birth to a most handsome black bull calf, and as soon as he appeared she began licking him, and butting him with her head and goading him to stand alone. She spent two hours at this task, then began mooing softly as if to attract the attention of the others, but when they ambled over to inspect her new calf, nudging it with their snouts, she made short and ineffectual charges at them, as if to prove that the calf was hers.

Among the bison that came to inspect the new calf was Rufous, and his nosy intrusion was an error he would regret. The newborn calf liked the smell of Rufous and for a few moments rubbed its small head against his leg. Some intuition told the calf that there would be no milk in that quarter, and he returned to his mother. But the damage had been done.

Now came the days which would be most crucial in the life of this little bison. Within a brief period it had to imprint on its mind the image of its mother, her smell, her feel, the taste of her milk, her look, the sound of her call. Because if it failed to make this indelible and vital connection, it might become unattached when the herd moved and be lost in the strangling dust. If this happened, it would survive only a few hours, for the wolves and vultures, seeing its plight, would close in.

Therefore the mother cow was careful to allow it to nuzzle her, to taste her milk, to smell her urine and to hear her cry. She attended the calf constantly, and when it moved among the other calves that were being born at this time she tried to train him to respond to her cry.

But the calf had proved its inquisitiveness by making friends with Rufous shortly after its birth, and it continued this behavior, moving from one adult to another and failing to establish an indelible impression of its own mother. She tried frantically to correct this defect, but her baby bull would wander.

One of its strongest memories was of the smell of Rufous, and as the days progressed it tried to associate more with the bull and less with its mother, trying even to get milk from Rufous. This irritated the bull, who knocked the confused infant away. The little fellow rolled over in the dust, got up bewildered and ran after another adult bull.

At this point, a fairly large herd of strange bison from the north moved onto the feeding ground, and there was a general milling about of animals, so that the baby bull became lost at the edge of the swirling crush. The two herds were excited enough by their chance meeting, but now they detected strange movement to the west, and this triggered precipitate action on the flank, which quickly communicated itself to the mass. A stampede began, and those calves which had been strongly imprinted by their mothers performed miraculously: no matter how swiftly their mothers ran nor how deftly they dodged, the calves kept up with them stride for stride, their little noses often pressed against their mothers’ flanks.