HE WAS A COUREUR DE BOIS, ONE WHO RUNS IN THE WOODS, and where he came from, no one knew.

He was a small, dark Frenchman who wore the red knitted cap of Quebec, and his name was Pasquinel. No Henri or Ba’tees or Pierre. No nickname, either. Just the three full syllables Pas-qui-nel.

He was a solitary trader with Indians, none better, and in his spacious canoe he carried beads from Paris, silver from Germany, blankets from Canada and bright cloth from New Orleans. With a knife, a gun and a hatchet for saplings, he was ready for work.

He dressed like an Indian, which was why men claimed he carried Indian blood: “Hidatsa, Assiniboin, mebbe Gros Ventre. He’s got Injun blood in there somewheres.” He wore trousers made of elk skin fringed along the seams, a buffalo-hide belt, a fringed jacket decorated with porcupine quills and deerskin moccasins—all made for him by some squaw.

As to where he came from, some claimed Montreal and the Mandan villages. Others said they had seen him in New Orleans in 1789. This was confirmed by a trader who worked the Missouri River: “I seen him in Saint Louis trading beaver in 17 and 89 and I asked him where he was from, and he said, ‘New Orleans.’ ” Both sides agreed that he was a man without fear.

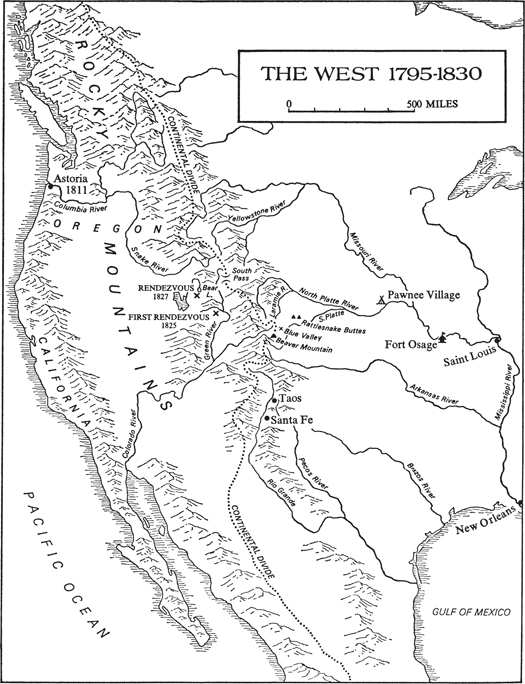

Early in December of 1795, in his big birch-bark canoe which he had been paddling upstream for five weeks, he appeared at the confluence of the Platte and the Missouri, determined to try his luck along the former.

The spot at which these rivers joined was one of the bleakest in North America. Mud flats deposited by the Platte reached halfway across the Missouri. Low trees obscured the shores, and swamps made it impossible for traders to erect a post. It was an ugly, forbidding place.

It was Pasquinel’s intention to paddle his canoe about five hundred miles up the Platte, reach there in midwinter, trade with whatever tribes he found, then bring the pelts down to the market in Saint Louis. It was a dangerous enterprise, one which required him to pass single-handed through Pawnee, Cheyenne and Arapaho country, going and coming. Chances for survival of a lone coureur were not great, but if he did succeed, rewards would be high, and that was the kind of gamble Pasquinel liked.

Pushing his red cap back on his head, he sang a song of his childhood as he entered the Platte:

“Nous étions trois capitaines

Nous étions trois capitaines

De la guerre revenant,

Brave, brave,

De la guerre revenant,

Bravement.”

He had paddled only a few miles when he realized that this river bore little resemblance to the Missouri. There progress depended solely upon strength of arm, but with the Platte he found himself often running out of water. Sandbars intruded and sometimes whole islands, which shifted when he touched them. Not only did he have to paddle; he had also to avoid being grounded on mud flats.

It’s only during the first part, he assured himself. Not enough current to scour the bottom.

But three days later the situation remained the same. He began to curse the river, setting a precedent for all who would follow. “Sale rivière,” he growled aloud in Montreal French. “Où a-t-elle passé?”

A cold spell came and what little water there was froze, and for some days he was immobilized, but this caused no fear. If he could not force his way upstream, he would look for Indians and trade for a few pelts.

Then the thaw came and he was able to proceed. To make a living trading for beaver it was necessary to be at the Indian camps in late winter, when the animals came out of hibernation, their fur sleek and thick. The same animal trapped in midsummer wasn’t worth a sou. Beaver trading was a winter job, and Pasquinel knew every trick the Canadians had developed for staying alive in freezing weather.

“Four Frenchmen can live where one Englishman would die,” they said in Detroit, and he believed it. He thought nothing of spending eight months alone in unexplored territory, if the Indians would allow him into their camps. If his canoe was destroyed, he could build another. If his stores were dumped, it didn’t matter, for he had invented a canny way of keeping his powder dry. But if Indians proved hostile, he stopped trading and got out. Only a fool would fight Indians if he didn’t have to.

Now he entered the land of the Pawnee, reputed in Saint Louis to be the most treacherous tribe. Fais attention! he warned himself, moving so stealthily that he spotted the Indian village before they saw him.

For one whole day he kept his canoe tucked inside a bank while he studied his potential foe. They seemed like those he had known in the north: buffalo hunters, a scalp here and there, low tipis, horses and probably a gun or two—everything was standard.

It was time to move. Methodically he laid out a supply of lead bullets, poured some powder, checked the oil patches required for tamping, and wiped the inside of his short-barreled fusil. His knife was in his belt and his hatchet close by. Taking a deep breath, he paddled his canoe out into the stream and was soon spotted.

Children ran down to the bank and began calling to him in a language he did not know. Grim-lipped, he nodded to them and they shouted back. Three young braves appeared, ready for trouble, and these he saluted with his paddle. Finally two dignified chiefs strode down, looking as if they intended to settle this matter. They indicated that he must pull his canoe ashore, but he kept to the middle of the river.

Angered, the two chiefs signaled a group of young men to plunge into the cold water and haul him ashore. Lithe bodies jumped in, walked easily to the middle of the river, and dragged him ashore. They tried to take his rifle, but he wrested it from them and warned in sign language that if they molested him, he would shoot the nearest chief. They drew back.

Then from the tipis came a tall, fine-looking chief with a very red complexion. Rude Water, they said his name was, and he demanded to know who Pasquinel was and what he was doing.

In sign language Pasquinel spoke for some minutes, explaining that he had come from Saint Louis, that he came in peace, that all he wanted was to trade for beaver. He concluded by saying that when he returned through Pawnee lands, he would bring Chief Rude Water many presents.

“Chief wants his present now,” a lieutenant said, so Pasquinel dug into his canoe and produced a silver bracelet for the chief and three cards of highly colored beads made in Paris and imported through Montreal. Genuflecting, he handed Rude Water the cards and indicated they were for his squaw.

“Chief has four squaws,” the lieutenant said, and Pasquinel brought out another card.

The parley continued all that day, with Pasquinel explaining that the Pawnee must be friends to the great King of France, but have nothing to do with the Americans, who had no king. Rude Water embraced Pasquinel and assured him that the Pawnee, greatest of the Indian tribes, were his friends, but that he must avoid the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who were horse stealers of the worst sort, and above all, the Ute, who were barbarians.

The desultory conversation resumed during the second day, with Rude Water inquiring as to why Pasquinel would venture into the plains without his woman, to which the Frenchman replied, “I have a wife … north, but she is not strong in paddling the canoe.” This the chief understood.

On the next day Rude Water still insisted on playing host, explaining that Pasquinel could not take his canoe up the Platte—too much mud, too little water. Pasquinel said he would like to try, but Rude Water kept inventing new obstacles. When Pasquinel finally got his canoe into the river, the entire village came down to watch him depart. Rude Water said, “When you come to where the rivers join, take the south. Many beaver.” The parting was so congenial that Pasquinel had to anticipate trouble.

He paddled upriver all day, suspecting from time to time that he was being followed. At dusk he pitched his tent ashore and ostentatiously appeared to sleep, but when darkness fell he slipped back to his canoe and lay in the bottom, waiting. As he expected, four Pawnee braves crept along the riverbank to steal his canoe. He waited till their probing hands were almost touching his.

Then, with fiendish yells and slashing knife, he rose from the bottom of the canoe, threw himself among the four, cutting and gouging and kicking. He was a one-man explosion, made doubly frightening by the dark. The four fled, and in the morning he continued upstream.

He had gone about fifty miles farther westward when he became aware that he was again being followed. Pawnee, he concluded. Same men.

So once more he laid out his bullets and honed his knife. He judged that if he could repel them one more time, they would leave him alone. He traveled carefully, avoiding mud flats and staying away from shore. He was watchful whenever he knelt to drink or stopped to relieve himself. It was an ugly, difficult game, which the Pawnee stood every chance of winning.

The showdown came at dawn. He had slept in the canoe, lodged against the southern shore, and was bending over to retrieve his paddle when a Pawnee arrow struck him in the middle of his back. A torturing pain coursed down his backbone as the slim arrow tip struck a nerve, and he might have fainted except for the challenge he had to meet.

Ignoring his wound, he grabbed for his fusil, raised it without panic, took aim and killed one of the braves. Ice-cool, he swabbed the barrel, poured his powder, inserted the patch, put in the ball, tamped it down, took aim and killed another. Methodically, while the blood ran down his back, he reloaded, but no third shot was required, because the Indians recognized that this tough little stranger had great magic.

That long winter’s day, with the low sun beating into his canoe, was one Pasquinel would not forget. Reaching blindly behind his back, he tugged at the arrow, but the barbed head had caught on bone and could not be dislodged.

He tried twisting the shaft, but the pain was too great. He tried pushing it in deeper, to get it past the bone, but produced a pain so excruciating that he feared losing consciousness. There was no solution but to leave the arrowhead imbedded, with the shaft protruding, and this he did.

For two days of intense pain he lay in his canoe face down, the arrow projecting upward. At intervals he would sit upright and try to paddle his canoe upstream, his back reacting in agony with each stroke but with the canoe moving ever farther from the Pawnee.

On the third day, when he was satisfied that the arrow was not poisoned and when the point was beginning to adjust to his nerve ends and muscles, he found that he could paddle with some ease, but now the river vanished. It contained no water deep enough for a canoe, and he had no alternative but to cache his spare provisions and proceed on foot.

The digging of a hiding place for the canoe called into play new muscles, and their movement caused new pain, which he alleviated by rotating the shaft until the flint accommodated itself. In one day he finished his job. Then he was ready to resume his journey afoot.

Like all coureurs, he used a stout buffalo-hide headstrap for managing his heavy burden. Passing the strap across his forehead, he allowed the two loose ends to fall down his back, where he fastened them to the load he had to carry. Normally his pack would have rested exactly where the shaft of the arrow protruded, so he had to drop the load several inches, allowing it to bounce off his rump.

In this manner he trailed along the Platte to that extraordinary place where the two branches of the river run side by side, sometimes barely separated, for many miles. There, lucky for him, he met two Cheyenne warriors and in sign language explained what had happened at the Pawnee camp. They became agitated and assured him that any man who fought the Pawnee was a friend. Placing him on his stomach, they tried to rip the arrow out by brute force, but the barbs could not be dislodged.

“Better cut it off beneath the skin,” they said.

“Go ahead,” Pasquinel said.

They handed him an arrow to bite on, then cut deep into his back, and after protracted sawing, they cut off the shaft. Within ten days Pasquinel was able to hoist his burden up from his rump and place it over the scar, where it rode not easily but well. Occasionally, as he hiked, he could feel the arrowhead adjusting itself, but each week it caused less pain.

He reached a Cheyenne village in late February 1796 and traded his bangles and blankets for more than a hundred beaver pelts, which he wadded into two compact bales. Wrapping them in moist deerskin which hardened when it dried, he produced packets like rock.

He now divested himself of every item not crucially needed, fastened the buffalo strap across his forehead and suspended the two bales from it. They weighed just under a hundred pounds each. His essential equipment, including rifle, ammunition, hatchet and trading goods, weighed another seventy pounds. Pasquinel, twenty-six years old that spring, and still suffering the ill effects of his wound, weighed somewhat less than a hundred and fifty pounds, yet he proposed to walk two hundred miles to where his canoe was cached.

Adjusting the huge load as if he were going to carry it from house to barn, he satisfied himself as to its balance and set forth. He created an extraordinary image: a small man, five-feet-four, with enormous shoulders and torso, gained from endless paddling, set upon matchstick legs. Day after day he trod eastward, keeping to the Platte and resting occasionally to drink from its muddy bed. He had to guard against wolves, lurking Indians and quicksand. Sometimes, to relieve the pressure on his temples, he squeezed a thumb beneath the buffalo band across his forehead.

He ate berries and a little pemmican he had made during the winter. He deemed it wise not to pitch camp and cook an antelope, for his fire might attract Indians. The worst of the journey, of course, was the spring insects, but he grew accustomed to them at his eyes, taking consolation in the fact that when summer came their numbers would diminish.

As he shuffled along, he muttered old songs, not for their words, which were trivial, but for their consoling rhythms, which kept him moving:

“My canoe is made of fine bark

Stripped from the whitest birch.

The seams are sewn with strong roots,

The paddles carved from white wood.

“I take this canoe and embark

Down the rapids, down the turbulence.

See how it speeds along

Never losing the current.

“I have traveled along great rivers, the whole St. Lawrence,

And have known the savage tribes and their various tongues.”

On one especially trying day he chanted this song for eight hours, allowing its monotony to pull him along. At dusk a pack of wolves came to the opposite bank for water. They must have recently feasted on a deer, for they looked at Pasquinel, drank and ambled off. This caused him to break into a silly song much loved by the coureurs:

“On my way I chanced to meet

Three cavaliers with horses neat.

Oh, you still make me laugh.

I’ll never go back home.

I have great fear of wolves.”

In this way he trudged back to where his canoe lay hidden, and when he got there he sighed with relief, for he suspected that he could not have held out much longer; the burden was simply too great. He rested for a day, then dug the canoe out and ate ravenously of the stored food. Tears did not come to his eyes, for he was not an emotional man, but he did give thanks to La Bonne Sainte Anne for his survival.

He loaded his canoe with the rest of the food and the two hundred and sixty pounds he had been carrying and climbed in, but within that day he discovered that the Platte had so little water he could not move. Disgusted, he got out and started pushing the canoe from behind, and in this way struggled down the middle of the river for about a hundred miles. There the water was only inches deep and he was faced with a difficult decision.

He could either abandon the canoe and resume portaging his pelts all the way to the Missouri, or he could camp where he was for six months and wait for the river to rise; he chose the latter. He built himself a small camp, to which Cheyenne reported from time to time, seeking tobacco. Thus the long summer of 1796 passed, and he lived well on antelope and deer, with now and then a buffalo tongue brought in by the Cheyenne. Twice he visited one of the Cheyenne villages and renewed acquaintance with the two braves who had cut the arrow from his back. One of their squaws was so convinced she could work the flint to the surface—she had done this for her father—that Pasquinel submitted to the ordeal, but she succeeded only in shifting the area of pain.

When the river finally rose, Pasquinel bade farewell to the Cheyenne and resumed his trail eastward. “Be careful of the Pawnee,” his friends warned.

“Rude Water is still my friend,” he assured them.

“With him be most careful of all,” they said.

When he reached the Pawnee lands, Rude Water greeted him as a son, then set eight braves to wrecking his canoe, stealing his rifle and running off with the precious bales of pelts. Unarmed and without food, Pasquinel was left alone, a hundred and fifty miles from the Missouri.

He did have his knife, and with it he grubbed roots and berries to keep alive. He walked by night, relieved in a sardonic way that he no longer had to carry his packs. By day he slept.

But he by no means intended merely to escape to the Missouri, there to be picked up by some passing white men. He was at war with the whole Pawnee nation and was determined to recover his pelts. He calculated that the Indians would appreciate their value and try to make contact with traders, and that the meeting place might be the confluence of the Platte and the Missouri.

When he reached that forbidding spot he made no effort to hail any of the Company boats he saw floating along with their own cargoes of skins. Instead, he hollowed out a hiding place among the roots of trees and waited. Two weeks passed, then three, and no Pawnee. It didn’t matter. He had time. Then in the fourth week he saw two canoes coming down the Platte, heavily laden. As he spied on them he felt a surge of excitement, for there were his pelts, just as he had wrapped them.

His joy was premature, for it looked as if the Indians intended paddling all the way to Saint Louis to dispose of their treasure. The two canoes entered the Missouri River, hesitated, and came back to the Platte. Pasquinel was much relieved when the Pawnee moved ashore and set up camp. They were going to wait for a downriver boat.

They waited. He waited. And one day down the Missouri came a pirogue bearing an improvised sign Saint Antoine. As soon as the Pawnee saw it they paddled out to flag it down. They had beaver, much beaver.

“Throw ’em aboard,” the rivermen cried.

While they haggled over price, Pasquinel swam into the middle of the stream, came silently onto the Pawnee canoes, turned one over and began slashing with his knife, killing two Pawnee. In the confusion the rivermen saw a chance to make off with the pelts, so they began firing point-blank at the surviving Indians.

Pasquinel swam alongside the boat, shouting in broken English, “Thees my peltries!” He was about to climb aboard when one of the rivermen had the presence of mind to club him over the head with an oar. He sank in the river.

He drifted face down, afraid to show signs of life lest they shoot at him, and after they disappeared around the bend he swam ashore. Shaking himself like a dog, and pressing water from his buckskin, he looked for a place to sleep. His canoe, his rifle, his store of beads and his pelts were gone: “Two years of work, I got one knife, one arrowhead in the back.”

He would not give up. If by some miracle he could reach Saint Louis before the pirates sold his furs, he might still reclaim them, and on that slim chance he acted.

He slept a few hours, then rose in the middle of the night and began running along paths that edged the river. When he reached the spot at which the Missouri turned for its long run to the east, he sought out a Sac village and traded his knife for an old canoe. With only such food as he could collect along the banks, he paddled tirelessly toward the Mississippi, hoping to overtake the robbers.

The day came when he detected a new odor, as if the Missouri were changing character, and in spite of his disappointment at not catching up with the pirates, he felt a rush of excitement. He paddled faster, and as he turned a final bend he saw before him the great, broad expanse of the Mississippi, that noble river flowing south, and he remembered the day on which he first saw this stream, far to the north. He had decided then to explore it all, and in the pleasure of meeting an old friend, he forgot his anger.

The Missouri ran much faster than the Mississippi and carried such a burden of sand and silt that it spewed a visible bar deep into the heart of the greater river; as Pasquinel rode the current far toward the Illinois shore, he could see that delicate line in the water where the mud of the Missouri touched the clear water of the Mississippi. For twenty miles downstream this line continued, two mighty rivers flowing side by side without mingling.

Rivermen said, “The Mississippi, she’s a lady. The Missouri, he’s a roughneck, plunging at her with muddy hands. For twenty miles she fights him off, keeping him at a distance, but in the end, like the mayor’s daughter who marries the coureur, she surrenders.”

When Pasquinel reached the calmer waters of the Mississippi he turned his canoe southward, and within the hour saw the sight which gladdened the hearts of all rivermen: the beautiful, low, white walls of Spain’s San Luis de Iluenses, queen of the south, mistress of the north and gateway to the west. When the little town first hove into view Pasquinel halted for a moment, lifted his paddle over his head, and giving the town its French name, muttered, “Saint Louis, we are coming home … empty-handed … for the last time.”

In that critical period in central North America a thousand small settlements were started, and some by the year 1796 had grown like Saint Louis into prosperous towns with nine hundred citizens, but most of those would subsequently languish. Saint Louis alone would grow into one of the world’s great cities. Why?

Brains. When Pierre Laclède, the Frenchman who started the settlement in 1764, did preliminary exploring to find a perfect site, he naturally chose that spot where the Missouri empties into the Mississippi; logic said that with two rivers the location had to be ideal, except that when he investigated the spot he found mud and brush twenty feet high in the trees. That could only mean floods and he abandoned that spot in a hurry.

Accompanied by his thirteen-year-old assistant, he moved a little farther south and found another attractive site, but it, too, had straw in the branches, so he continued to move south, league by league, and at the eighteenth mile he found what he was looking for: a solid bluff standing twenty to thirty feet above water, with two secure landing places upstream and down. This location provided everything needed for the growth of a major settlement: river port, lowlands for industry, higher sites for homes, fresh water, and to the west an endless forest.

Brains had done it. When other settlements along the Missouri and the Mississippi were under water during recurrent floods, Saint Louis rode high and clear. When other harbors silted up, the river scoured the waterfront at Saint Louis, keeping it clear of sand, so that commerce could continue. In 1796 no one could predict whether it was to thrive or not, but as Pasquinel paddled his canoe into the landing, he was satisfied on one point: “This is the best town on the river.”

As soon as he landed he started asking in French, “Have you seen the pirogue, Saint Antoine?” A fur buyer said, “Yes, it was sold for lumber.”

Pasquinel ran to the southern end of town, where a carpenter from New Orleans bought boats as they finished their run and broke them up for timber. Saint Antoine? “Yes. Broke it up two weeks ago.” Where did the men go? “Who knows? They sold their pelts and they’re gone.” Where are my pelts? “Part of some shipment on its way to New Orleans.” Bitter and without a sou, he moved about the town, cursing Indians and rivermen alike.

Saint Louis would have a confused history, owned by France, then Spain, then France again, then America. Officially it was now Spanish, but actually it was French. Indeed, even the Spanish governor was sometimes a Frenchman, and all of the businessmen. The latter fairly well controlled the fur trade, for they received licenses and monopolies from the Spanish government in New Orleans to trade on this or that river, and it was to them that individuals like Pasquinel had to look for both their financing and their legal permission to trade.

There was a Company, run by a combine of wealthy citizens; there were also private entrepreneurs who were granted monopolies and who then outfitted coureurs, and Pasquinel had worked for one of them. But after the present disaster this gentleman showed no further interest in sinking additional capital in such a risky venture. Pasquinel therefore moved from one French license holder to the next, trying to cadge money to outfit his next expedition: “You buy me a canoe, some silver, beads, cloth … I bring you plenty peltries.” No one was interested: “Pasquinel? What did he bring back last time? Nothing.”

Along the waterfront a riverman told him of a doctor who had recently fled the revolution in France: “Dr. Guisbert. Very clever man. He can cut that arrowhead out of your back.” He went to see the newcomer, an enthusiastic man, who told him, “On your trips you should read Voltaire and Rousseau. To understand why we no longer have a king in France.”

“I know nothing of France,” Pasquinel said.

“Good! I’ll lend you some books.”

“I can’t read.”

Dr. Guisbert inspected his back, moving the flint with his fingers, and said, “I’d leave it alone.” As Pasquinel replaced his shirt, Dr. Guisbert gave the flint a sudden push with his thumb, but the trapper barely winced. “Good,” Guisbert said. “If you can stand the pain, it’s doing no damage.”

He liked the spunky coureur and asked, “Where’d you get that wound?” Pasquinel haltingly began to explain, and Guisbert became so interested in beaver pelts and Cheyenne villages that the conversation continued for some time, with the doctor saying impulsively, “One of my patients is a merchant who has a trading license from the governor. Perhaps we can form a partnership, we three.”

And so, staked with the doctor’s money and under the protection of the merchant’s license, Pasquinel prepared once more for the river.

He bought himself a new rifle, twice the trade goods he had had before, and a sturdy canoe. At the wharf Dr. Guisbert told him, “You wonder why I risk my money? When I pushed that arrowhead deeper into your back, I know it hurt very much. A man doesn’t learn to bear pain like that without having courage. I think you’ll bring back pelts.”

On New Year’s Day, 1797, Pasquinel reappeared at the Pawnee village to settle affairs with Chief Rude Water: “If you send your braves to attack me this time, I will kill them and then kill you. But that won’t happen, because you and I are trusted friends.” A calumet was smoked, and he told Rude Water, “Last year we fight. Frenchmen run off with pelts. This year we friends.” Again the calumet was smoked, and Pasquinel concluded the deal: “I come back, I give you one pelt in five.”

Rude Water assigned four braves to escort Pasquinel to the point where the Platte ran out of water, and there they helped him cache his canoe, bidding him good luck as he departed for alien country.

That winter he traded well with the Cheyenne, but when he had assembled two bales of pelts, a Ute war party stumbled upon him and decided this was a good chance to grab a rifle. For two days he defended himself and was able to survive only because the Ute did not learn quickly how long it took him to reload. In the end one daring brave dashed in, touched him with his coup-stick and retreated, claiming victory. This satisfied the Indians and they withdrew.

This year, remembering the torture of that previous portage, he had planned to lug the pelts downstream one bale at a time: take the first bale down, cache it, come back for the second; cache it, then proceed with the first in a continuing operation. But with the Ute on the move, he judged that he must not risk so prolonged an operation, and he loaded himself as before.

For thirty-two days he staggered down the river, his muscles bulging, his eyes nearly popping from his head. When he reached the hiding place for his canoe, he was in better condition than when he started. Placing the freight in his fragile craft, he pushed it downstream across the sandbars of summer. He had covered less than a hundred miles when he saw with quiet joy four Pawnee braves approaching to help.

Standing ankle-deep in the Platte, he hailed them. “Many furs,” he said in sign language.

“Big happening!” they said in sign, pointing downstream toward their village. “We have white man.”

“Who?” They could not explain except to say, “Red hair, red beard.”

As they neared the village Chief Rude Water came to greet them, holding in his hand a buffalo thong, the far end of which was attached to the neck of a tall red-bearded young white man about nineteen years old. With a neat flick of the halter, Rude Water tossed him forward so that he stood facing Pasquinel, and in this unusual manner the coureur met Alexander McKeag.

“Depuis combien de temps êtes-vous ici?” Pasquinel asked.

“Six months,” McKeag replied in broken French, using a low, gentle voice. “Captured tryin’ to go upstream … to trade for beaver.”

“Il y a des castors là-bas,” Pasquinel said.

He showed Rude Water the two heavy bales and reminded him that one-fifth of the pelts belonged to the Pawnee, but when the braves started to rip the bales open, Pasquinel shouted for them to stop. He then tried to explain in sign that it would be more profitable to the Indians if they allowed him, Pasquinel, to sell the pelts in Saint Louis.

“I speak Pawnee,” McKeag interrupted quietly.

“Tell him he’ll get more goods.”

In this way Alexander McKeag, refugee from a tyrannical laird in the Highlands of Scotland—whom he had clubbed over the head with a knotted walking stick—started his career as interpreter. He convinced Chief Rude Water that the Indians would profit if they allowed Pasquinel to represent them in Saint Louis, whereupon Rude Water asked, “How do we know he will bring the goods back?”

When this was translated, the Frenchman said, “I am Pasquinel. I came among you unafraid.”

The pact was sealed with a calumet, and after Pasquinel had smoked his share, he stepped to McKeag and untied the buffalo thong. “Dites-leur que vous êtes mon associé,” he said, and in this way the partnership was formed.

Their first venture was a dandy. Pasquinel huddled with Rude Water and said, “Remember those rivermen? Killed your braves. Stole our pelts.” Rude Water did remember. “They ought to be coming back down the river about now. Lend me some braves who can swim.”

A war party of nine canoed down to the Missouri and camped there for some weeks, watching several fine boats drift past, Saint Geneviève, Saint Michel, laden with pelts from the Mandan villages.

And then the boat they waited for appeared, long and ragged, like the Saint Antoine, with the same rough men lounging with rifles, waiting for something to shoot at.

“Maintenant,” Pasquinel whispered to McKeag. “Vous partez. They won’t know you.”

So McKeag pushed his canoe into the Missouri and called, “Hey there! Passage to Saint Louis? I have pelts.”

The boat slowed. The man at the rudder fanned water and another with a pole worked against the current. The leader studied McKeag, saw he was under twenty, and cried cheerfully, “Sure. Throw the pelts up.” One of the men slipped to the rear, taking a heavy oar with which to knock McKeag senseless once the pelts were aboard.

As the rivermen reached for the bales, Pasquinel put a bullet through the head of the leader. With terrifying calm he handed the smoking rifle to a Pawnee helper, took McKeag’s rifle and drilled a bullet into the man lurking with the oar. He then reached for a third gun, but by this time the Pawnee braves were climbing aboard the flatboat, where the remaining crew were massacred. Young McKeag, who had never seen Indians lift a scalp, was shaking by the time Pasquinel got aboard.

“I didn’t think we’d kill them,” he said softly.

Pasquinel said, “L’année dernière ils ont essayé de me tuer.”

“How do you know they’re the same men?” McKeag asked.

“That one I know. That one too. The others? Mauvais compagnons vous apportent de la mal chance—Bad companions bring bad luck.”

Young McKeag was impressed by the assurance with which Pasquinel operated; the Frenchman was only eight years older, but he always seemed to know what to do. “Throw the bodies overboard,” he told the Pawnee, and after McKeag interpreted this, he added, “Tell them they can have anything on the boat they want.” McKeag protested that he and Pasquinel could use some of the gear, but the Frenchman snapped, “I want it to look as if pirates had struck,” and he smiled thinly as the braves did their ransacking. When the Pawnee headed their canoes back toward the Platte, McKeag started to wash down the decks, but Pasquinel stopped him: “I want blood to show—especially the hair—when we talk to the soldiers in Saint Louis.”

Pasquinel defeated and Pasquinel victorious were two different men. This year he brought the pirogue with its cargo of furs to the Company landing like a Roman proconsul returning from Dacia. Seeking out the merchants who had invested in the pirogue, he described the savage attack by the Pawnee, the scalping of the crew, McKeag’s bravery and his own gunning down of the Indian miscreants. He displayed the matted hair, the blood, and bowed gracefully when they applauded his defense of their property. He turned his own bales over to Dr. Guisbert.

He began to enjoy himself in Saint Louis. Without money Pasquinel had been withdrawn; with it he became a robust, singing drunk. The lonely discipline of the prairie vanished and he spent his profits lavishly, for the sheer love of spending. He financed vagrants for explorations they would never make, and paid off old debts with bonuses.

After two months of this, he was broke. Sobering up, he applied to Dr. Guisbert for his next advance. The doctor had been expecting the call and did not flinch when Pasquinel said, “This year, twice as much. I have a partner now.”

He and McKeag paddled slowly upstream with enough trade guns for Chief Rude Water to drive the Arapaho and Cheyenne clear off the plains. At the village McKeag saw the white men’s scalps and felt sick, but Pasquinel told him, “The coureur, he ends as a scalp. Vous peut-être, et moi aussi.”

The winter of 1799 was the one they spent at Beaver Creek, meeting for the first time Lame Beaver of the Arapaho. It was that winter, too, when McKeag performed the impossible, learning a little Arapaho so that he could later serve as interpreter for them.

They formed a strange pair, this short stocky Frenchman and this slim red-bearded Scot. Each was taciturn when on the prairie; neither pried into the affairs of the other. Without commenting on the fact, McKeag had now heard Pasquinel tell others that his wife was in Montreal, Detroit and New Orleans, and he began to suspect that there was none. It would never have occurred to him to ask outright, “Pasquinel, you married?” for that would be intrusive.

When McKeag developed into a competent shot, Pasquinel taught him the one overriding secret of successful trading: “Keep your powder dry.”

“How do you do that when the canoe upsets?”

“Simple. You buy your powder, then you buy your lead for the bullets. With the lead you make a little keg … very tight lid … wax on top … sealed in deerskin.”

“Why not buy the keg?”

“Ah! That’s the secret. You make the keg out of just enough lead to be melted into bullets for the powder. When the powder’s gone, the keg’s gone.”

He taught McKeag how to use the two-ball mold into which the melted lead was poured to produce good bullets; he gave a further exhibition of his resourcefulness when the Scotsman broke the wooden stock on his rifle. To McKeag it looked as if his gun was ruined, for he could not fit it against his shoulder or take aim, but for Pasquinel the problem was simple.

He fitted the three pieces of wood together, then steamed a chunk of buffalo hide until it was gelatinous. With a bone needle and elk sinew he sewed the skin as tightly as he could about the broken wood, but McKeag tried it and said, “Still wobbles.”

“Attends!” Pasquinel said, and he placed the rifle with its pliable buffalo patch in winter sunlight, and as the moisture was drawn out, the skin tightened, becoming harder than wood, until the stock was stronger than when McKeag bought it.

One sun-filled morning in May, as they were wandering together north of Rattlesnake Buttes looking for antelope, McKeag had a flash of insight: it occurred to him that he and Pasquinel were the freest men in the world. They were bound by nothing; they owed no one allegiance; they could move as they wished over an empire larger than France or Scotland; they slept where they willed, worked when they wished, and ate well from the land’s bounty.

As he looked at the boundless horizon that lovely day he appreciated what freedom meant: no Highland laird before whom he must grab his forelock. Pasquinel was subservient to no Montreal banker. They were free men, utterly free.

He was so moved by this discovery that he wanted to share it with Pasquinel. “We are free,” he said. And Pasquinel, looking to the east, replied, “They will be moving upon us soon.” And McKeag felt a shadow encroaching upon his freedom, and after that day he never felt quite so untrammeled.

In the fall of 1799 Dr. Guisbert staked them for an exploratory trip up the North Platte. It was a difficult journey, past strange formations and along lonely stretches of near-desert. They saw congregations of rock which resembled buildings in some dream city. They saw needles, and passes between red cliffs, and long defiles through ghostly white mountains.

“Impossible country,” McKeag said one evening as they camped among strange towers.

“Il y a des castors,” Pasquinel replied.

When they left the area of monuments they entered territory occupied by a tribe of Dakota, and the Indians sent braves to notify them that they could not continue their march. Pasquinel directed McKeag to say, “We shall continue. Trading beaver.”

The Dakota, furious at their insolence, withdrew behind a small hill, and Pasquinel warned McKeag, “Tonight we fight for our trade.” And he showed the young Scot how best to prepare for an Indian fight: “Be ready to kill or be killed. Then see that it doesn’t happen.”

Just before dusk the Dakota swept in on horseback, with every apparent intention of destroying the two intruders. “Don’t fire!” Pasquinel warned McKeag. But Pasquinel did. He sent a bullet well in front of the warriors. Then he took McKeag’s gun and sent one harmlessly behind. The Indians wheeled, came roaring back, and this time Pasquinel held his fire altogether. One Dakota touched McKeag, then off they stormed, shouting and kicking their horses.

Next day Pasquinel calmly packed his gear, stowed his rifles and led the way upriver. At the Dakota camp he conducted powwow with the chiefs, giving them presents and assuring them there would be more on the return trip. No word was said of the attack the previous night or of the bullets fired.

When the traders were safely out of Dakota territory, Pasquinel said, “If you give an Indian a fair chance, you can avoid killing.” He paused. “In years to come those braves will sit around the campfire and tell about the coup they made on the two white men … the whistling bullets.” He smiled sardonically, then added, “And you will sit in Scotland and tell of the tomahawks and the arrows.”

In this manner they made their way among the various tribes. At each step they were surrounded, though they could not see them, by thousands of courageous Indians who could have destroyed them. There were skirmishes, but if they held firm and did not run, they were allowed to move westward.

The skirmishes were testings, like the ancient war parties the Arapaho had sent against the Pawnee and the Pawnee against the Comanche. They were moves in an elaborate game by which the white man probed and the Indian reacted, and when word passed through the tribes, “Pasquinel, he can be trusted,” it was better than a passport. A multitude of coureurs from Montreal, St. Louis and Oregon would in the years ahead traverse Indian country, and for every man who was killed, six hundred would pass in safety.

Pasquinel and McKeag decided to winter at one of the loveliest spots in all America, that trim peninsula formed where the North Platte was joined by a dark, swift river sweeping in from the west. In later years it would be called after a French coureur de bois who had once trapped with Pasquinel, Jacques La Ramee. No finer river crossed the plains; deep and clean, the Laramie formed a haven for beaver. Wild turkey nested and deer came to feed. Ducks sought refuge, and elk. Buffalo used it as their watering spot, and on dead branches, brown-gray hawks stood guard.

In that winter of 1800 the team acquired six bales of superior peltries and were about to head south when a band of Shoshone attacked. The Indians were driven off, but returned to lay siege. A desultory gunfight occurred, but nothing much would have happened except that one Shoshone dashed into camp, astonished McKeag by counting coup on him, and the Scotsman reached for his gun, whereupon the Indian struck him with a tomahawk, gashing his right shoulder.

The wound festered. McKeag became delirious, and any thought of his lugging bales east that June had to be abandoned.

In lucid moments, when McKeag comprehended the dangerous position in which he had placed his partner, he urged Pasquinel to move out: “Begone with you. I’m bound to die.” Pasquinel did not bother to answer. Grimly but with tenderness he tended his stricken partner.

The wound worsened. It became repulsive and threatened death; its smell contaminated the hut. In one of his lucid moments McKeag begged, “Cut it off.” Pasquinel replied, “If you had no arm, how would you fire a gun?”

By mid-July it appeared that McKeag was doomed; again he pleaded with Pasquinel to amputate the arm, and again the Frenchman refused. Instead, he took his ax, chopped a mass of fine wood and built a fire. When it crackled, he plunged the ax in, allowing it to become red-hot. Without warning, he slammed the incandescent metal against the corrupt shoulder, pinning McKeag to the paillasse as he did so.

There was a stench of burning flesh, a sound of screaming. Pasquinel maintained pressure on the ax until he judged that he had done enough. This drastic treatment halted the corruption; it also permanently destroyed some of the muscles in McKeag’s right arm. Henceforth it would be cocked at the elbow. When he realized what Pasquinel had done, or rather not done, he ranted, “Why didn’t you cut it off altogether?” He lapsed into delirium and would probably have died had not Lame Beaver’s band of Arapaho wandered by on the prowl for buffalo.

When women from the camp saw McKeag’s condition they knew what had to be done, and they sent girls into the stream beds, looking for those plants which were effective in poultices, and soon the swelling subsided.

“Bad scar,” Blue Leaf told McKeag in Arapaho as she tended him.

“He’ll use his arm,” Pasquinel asserted when this was translated.

One morning while three Arapaho women were watching him—and thinking he was asleep—they began women’s talk about the various braves in camp, and in the robust manner of Indian women, who were never intimidated by their men, they began discussing the sexual equipment of the braves, pointing out any conspicuous deficiencies. Such talk disturbed McKeag, who had been reared in a strict Presbyterian home, and he became even more uncomfortable as the gossip grew rowdier, with even Lame Beaver’s capacity reviewed and found wanting.

At this point Blue Leaf came in and the women stopped their talking, but she could guess what the subject of their conversation had been. “This one speaks our language,” she reminded them, and the three watchers moved to the bed to see if McKeag was awake, and when they were satisfied that he was not, they resumed their chatter and one said that she had seen him when she bathed him and that he seemed even poorer than one of Our People. Blue Leaf silenced them and drove them from the lodge; then she roused McKeag to poultice his shoulder.

Among the Indian girls who gathered medicinal plants was Clay Basket, then eleven and promising to be as pretty as her mother. During the long afternoons she sat with McKeag, learning a little English. She warned him not to call her father chief, for he had never been one. She tried to explain why, but could not make herself clear. Instead, she fetched the buffalo hide which recounted his many coups, and there McKeag saw the Arapaho version of Lame Beaver’s invasion of their tipi two years before. Looking at the impressive record of Lame Beaver’s feats, he told Clay Basket, “Your father chief … big chief,” and she was pleased.

It was now too late for the traders to return down the Platte, so they prepared to winter at the confluence, strengthening the walls of their hut and making pemmican. McKeag was too weak to hunt, nor was it known whether he would ever be able to fire a gun again, for his shoulder remained a gaping wound. He stayed in the lodge, doing what work he could and talking with Clay Basket about why the Cheyenne were trusted allies and the Comanche wicked enemies.

One afternoon Pasquinel returned with an antelope. He was in an evil mood and with a curse threw the animal at McKeag’s feet. Then he grabbed McKeag’s rifle and pointed to the stock that he had mended with buffalo hide.

“Goddamn! Same thing your shoulder!” He searched for English words, found none, and in frustration, resorted to a method of direct communication which shocked the Indian girl. Pulling his right arm far back, he struck McKeag in the wounded shoulder so forcefully that he knocked him down. Before McKeag could regain his feet, he struck him twice more, then thrust the gun at him, shouting, “Use it. Take gun. Goddamn, use it.” With that he shoved McKeag from the hut.

McKeag, followed by Clay Basket, walked to the banks of the river, and with considerable pain, placed the gunstock against his right shoulder, but he could not muster the strength to lift his hand to the trigger. Sweat stood on his forehead, and against his will, for he did not want an Indian child to see him cry, tears filled his eyes. “It’s too much,” he groaned.

He would have halted the experiment at that point, but Clay Basket now understood what Pasquinel intended. Either McKeag must learn to function again, or die during the winter. She forced him to lodge the rifle once more against his shoulder. Then taking his right hand in hers, she slowly raised his arm, breaking the scar tissue, until his hand touched the trigger. He bit his lip, held the hand there for some seconds, then let it fall.

Again and again Clay Basket forced the hand up, and there the lesson ended for that day. McKeag refused to speak to Pasquinel, who ignored him.

On the third day Clay Basket lifted the hand easily into position, and when she was satisfied that McKeag could do this by himself, she took the rifle from him, swabbed it, poured in some powder and inserted a ball, as she had learned to do. Ramming the load home, she thrust the gun back into his hands and said, “Now.”

“I can’t,” McKeag protested, refusing to accept the gun.

“Now,” she cried.

She badgered him into taking the gun and raising it into firing position. Slowly she brought his right hand to the stock, placing his forefinger on the trigger. “Now,” she said softly.

Apprehensive of the pain that was about to strike him, McKeag could not pull the trigger. Clay Basket looked at him with pity, thinking of how her father had hung suspended by his breast for a whole day. When it was apparent that McKeag was not going to fire, she raised herself on her toes, placed her small finger over his and gave a powerful jerk backward.

With a shattering explosion the gun fired. She had poured enough powder to fill a cannon, and when Pasquinel rushed from the lodge, all he could see was a cloud of black smoke and McKeag on the ground.

His wound was opened by the recoil, but Blue Leaf stanched the flow of blood with wet leaves. A week later, when scar tissue had barely begun to form, Clay Basket had McKeag out again with the gun. “This time I load,” he said, but when he actually held the stock against his shoulder, the pain was too much. So once again the girl slipped her finger over his and pulled the trigger. When he voluntarily reloaded and fired again, she was so proud of his courage, she shyly pressed her lips against his beard.

It was now time for the Arapaho to move on, to locate one more herd whose meat would sustain them through the winter. Lame Beaver came by to say farewell, and Blue Leaf, stately as a spruce, assured McKeag that his shoulder was now mended. Clay Basket, bright in beads, gently touched their faces and told them in English, “I know you come back.”

The snows came and winds swept down from the north. The river froze and even deer had trouble finding water. From aloft eagles inspected the camp, and the two men sat in their lodge and waited.

There were days, of course, when the winds ceased and the sun shone as if it were summer. Then the partners, naked to the waist, worked outdoors. In their lodges the beaver began to stir, as if this were spring, and elk grazed in the meadows.

But such interludes were followed by storms and temperatures thirty degrees below zero. For three weeks that February the men were snowed under: drifts came clear across their lodge, and like animals they had to burrow out. This caused no concern; they had a comfortable supply of meat and wood. For water they could melt snow—God knows, there was enough of it.

They had no books … no loss … neither could read. They had no work, no place to go, no problem but survival. So there, deep beneath the snow, they waited. For five hundred miles in any direction there were no white men, unless perhaps some stubborn voyageur from Detroit had holed up in some valley to the north, like them, awaiting spring.

Occasionally they talked, but mostly they sat in silence. Already they had six bales of beaver, worth at least $3600, plus prospects for six more during the coming season. They were rich men, if they could sneak the pelts back through the Indian country.

On the rare occasions when they did speak they used a strange language: French-Pawnee-English. McKeag’s native tongue was Gaelic, a poetic language spoken softly. When he uttered words it was with a certain shyness; Pasquinel was more glib. But even so, whole days passed with hardly a word being said.

Then the snowfall diminished and drifts began to melt. Mountain streams grew strong and the river became a torrent. Beaver in their lodges began to stir and moose dropped last year’s antlers. Buffalo pawed at the earth and wild turkeys came down from their winter roosts. During warm spells rattlesnakes emerged from deep rocky crevices. One day when the full wonder of spring was about them, Pasquinel said, “We trade six weeks, go home.”

As they were returning down the Missouri, along that endless east-west reach the river takes before it enters the Mississippi, their rhythmic paddling was interrupted by the appearance of a solitary man bringing a canoe upstream and shouting their names: “Pasquinel! McKeag! Great news for you.”

Sweating with nervousness, he pulled his canoe alongside theirs and introduced himself: “Joseph Bean, Kentucky.” His attention focused immediately on the bales, and he said, “What good luck I bring you. I act as agent for Hermann Bockweiss.” He stopped, as if this startling information carried its own interpretation.

“Qui est-il?” Pasquinel asked.

“Silversmith from Germany. Makes wonderful trinkets for the Indian trade.” Pasquinel shrugged his shoulders, and Bean continued frenetically: “Came to Saint Louis last January. Heard you were the best trader on the river. Says he will advance the money for your trips.”

Pasquinel replied brusquely, “No need. I work Dr. Guisbert.”

“Aha!” the American cried. “That’s just it! Dr. Guisbert … his partner died and he moved to New Orleans for a rich life downriver.” He explained the new situation in Saint Louis: Pasquinel would deliver Guisbert’s pelts to the German, who would sell and send Dr. Guisbert …

On and on Bean went, an irritating man, perspiring constantly, but so insistent that the traders had to consider this invitation. When they finally landed at Saint Louis they saw gleaming down at them from the shore the round, plump face of Hermann Bockweiss, silversmith, lately from Munich.

He occupied the house formerly owned by Dr. Guisbert, and in the rooms that had once been devoted to medicine he plied his delicate trade. Using silver imported from Germany and brought up the Mississippi from New Orleans, he fabricated not only the trinkets so loved by the Indians but also the ornate jewelry desired by women as far north as Detroit.

His own childlike enthusiasm enabled him to predict what gleaming device would catch an Indian’s fancy. It was he who invented the ear wheel for the squaws, dainty pendants enclosing tiny wheels which revolved, and silver-inlaid tomahawks for the braves. He offered a set of five half-moon pins for women and three wide bands for the upper arm of a man. His specialty was the fish-eyed brooch, an ordinary flat pin upon which he had deposited a score of small, glistening beads of silver; his most impressive item was the silver-chased peace pipe, a stunning affair adorned with pendants of multicolored beads.

At the same time this canny German realized that in the long run his profits would have to come from whatever trade he established with the local gentry, and he had real skill in combining the demands of French elegance with the sturdy approach to silver design he had learned in Bavaria. Indeed, a Bockweiss piece tended to become an heirloom, a subtle blending of two cultures.

His relationship with Pasquinel was interesting. Since Saint Louis still had fewer than a thousand inhabitants, there was no public hotel, and coureurs from the west had to find such lodging as they could in private homes. Most families did not care to board the filthy and profane men, but Bockweiss insisted that Pasquinel and McKeag accept his hospitality. He had two daughters, Lise, the strong-minded one, and Grete, the coquette, and he convinced himself that one day the coureurs would become his sons-in-law. Normally a father in Saint Louis would have preferred his daughters to marry more substantial types, say, established businessmen, but Bockweiss had not made the long journey from Munich to Saint Louis because he was cautious. He was a romantic who relished the idea of probing unsettled prairies and saw that McKeag and Pasquinel fitted the pattern of his new country. So the coureurs moved in to rooms above the shop, and Bockweiss noticed with gratification that Lise was developing an interest in Pasquinel, while Grete confided that she thought McKeag congenial.

There was competition. Local girls, spotting the way Pasquinel spent his money buying presents for anyone connected with the fur trade, thought he might make a good husband. He was generous. He was entertaining. In looks … well, he was small but he was not ridiculous. Best of all, he seemed to be lucky.

They made known their interest, but Pasquinel excused himself, as he always did, on grounds that he already had a wife in Quebec. He was willing to give them money, pay for their drinks and bed with them as chance provided, but he could express no interest in marriage.

Lise Bockweiss was not so easy to dispose of. She was a solid, forthright girl with all the domestic qualifications a husband might expect. She also had a sense of humor and could appreciate the comedy in watching the New Orleans French girls trying to catch this elusive trader. She was taller than Pasquinel but she had the knack of making him seem important when she was with him, and from time to time even Pasquinel had the fleeting thought: This one could make “une bonne femme.”

The four ate together frequently, but between Grete and McKeag little was happening. He was timorous with ladies and blushed as red as his beard when pretty Grete teased, “I’ll bet you have a squaw hidden upstream.” It was not long before young Grete concluded that there was little future for her in wooing McKeag, and she turned her attentions to a shopkeeper who appreciated her.

It was more difficult for Pasquinel to evade Lise. For one thing, her father took a heavy-handed interest in the courtship; he was aware that Lise was seriously considering the coureur and he did not propose to let the Frenchman slip away. Bockweiss could not believe Pasquinel’s vague talk of having a wife. He persuaded the coureur to visit with him in his shop, and in the process of explaining how he cast his jewelry he found opportunity to speak of his daughter: “That one has a solid head on her shoulders. A man would always be proud of that one.”

The silver reached him in ingots, which he melted in a small furnace activated by an arm-powered bellows: “Lise’s mother taught her how to cook … good.”

When the silver assumed liquid form, he poured it meticulously into molds shaped like butterflies, or wheels, or arm bracelets: “It’s no easy thing to bring two daughters all the way from Germany, but when they are both angels, especially Lise, it’s worth it.”

When the silver cooled, he used delicate files to remove any excess, catching it for reuse later. Then he took the pieces to a buffer wheel, turned by a foot pedal, and as he pumped he said, “A man with a good business like you ought to marry. I myself plan to marry again next year, but of course, finding a good woman isn’t easy.”

He now took the pieces and began the delicate etching and decoration which made a Bockweiss silver piece so desirable. He had large, fat fingers which seemed unsuitable for intricate work, but he used his tools with such skill that he could carve almost any design: “Pasquinel, let me be frank. I sell a piece like this for ten dollars. I’m going to be a wealthy man. With my daughters, especially Lise, I can afford to be generous. You would have a fixed home here in Saint Louis. A fixed home is something.”

As the time approached for the traders to return to their rivers, Lise Bockweiss took over where her father had stopped. She gave a dinner to which Pasquinel was invited and showed him concentrated attention, after which her father took the Frenchman aside and said, “As long as the world lasts, women will want jewelry and Indians will want trinkets. You do the trading. I’ll make the silver. It will be a good partnership.”

He continued expansively: “And as your partner, Pasquinel, I would be very happy … that is … should you at some point in time wish to join my family.” This was said with Germanic gravity and with such obvious regard for Lise’s welfare that not even Pasquinel could treat it jokingly. A proposal was being made, one most advantageous, and he was forced to give it attention.

McKeag, watching this from a comfortable distance, since Grete was no longer applying pressure on him, saw that his partner was being maneuvered into marriage, and he began to take seriously Pasquinel’s repeated statements that he had a wife somewhere else, Montreal or New Orleans or Quebec. He was not surprised, therefore, when Bockweiss invited him to the shop one day to speak of this matter, but he was taken aback when he found Grete’s shopkeeper there, accompanied by a blonde from New Orleans.

“Herr McKeag,” Bockweiss said bluntly, “this young lady has told us that your partner Pasquinel has a wife in New Orleans. What of that?”

McKeag took a deep breath, looked first at the girl, then at the shopkeeper, and said, “Pasquinel jokes about this … to keep from getting trapped. One time he says he has a wife in Montreal, another time Quebec. I suppose he said New Orleans too.”

Bockweiss laughed nervously, but with obvious relief. The blonde, however, felt that she had been insulted and was not disposed to let the matter drop. “He told me nothing. I heard it from a New Orleans girl. When I told her that I liked Pasquinel, she said, ‘No good. He has a wife in New Orleans.’ ”

“Did she know the wife?” Bockweiss asked.

“How do I know?”

“You could ask her.”

“Ask? Ask? She’s gone.”

The meeting was inconclusive, and Bockweiss, feeling an impropriety in having raised such a question about a potential son-in-law, yet wanting reassurance as a father, suggested that perhaps McKeag might want to question his partner, but at this the Scotsman rebelled. Blushing deeply, he fumbled, “I wouldn’t know … I couldn’t.”

So the businessman was deputized to interrogate Pasquinel, and it was a futile interview. The little Frenchman laughed and said, “This town is too much. I better get back to the Indians.”

“But do you have a wife in New Orleans?” the man pressed.

“No.”

After this reassurance the Bockweiss family concluded there was no impediment. Plans went forward for a wedding, even though the groom had not said definitely that he was entering into the union, and finally Bockweiss put the matter to him bluntly: “Can we have the wedding before you go back to the plains?”

“Yes.”

It was a charming affair. Normally the local French would have ignored such a wedding, but the Bockweiss family came from South Germany, an area friendly to France, and in addition, were Catholic, which made them doubly welcome in the community. At the celebration, Bockweiss and his daughters made a favorable and lasting impression on the inhabitants, while Pasquinel, looking very short and muscular beside his taller German wife, behaved himself, and the approving news was flashed through the crowd: “He’s turning over whatever savings he has to his wife. Bockweiss has acquired a grant of land from the governor, and she’s building a big house.” Before the coureurs left Saint Louis, the new bride assured McKeag, “We’ll always keep one room for you,” but when the canoe was heading west the Scotsman thought, One more freedom gone.

In the late summer of 1803, as they came down the Platte from Rattlesnake Buttes with seven bales of beaver, they heard at the Pawnee village news that was doubly sad. Chief Rude Water had been slain by an Arapaho war party: “Big devil Lame Beaver, he staked himself out. Shot Rude Water.”

“Pasquinel!” McKeag called. “You hear that? The Arapaho who helped us up north, Lame Beaver. He killed Rude Water.”

“What happened to Lame Beaver?”

McKeag translated this for the Pawnee, and they replied, “We killed him.”

Pasquinel shook his head sadly. “Deux braves hommes … morts. Dommage, dommage.”

Then the Pawnee continued with additional information that proved even more startling: “Lame Beaver killed Rude Water only because he used special bullets.” And they showed Pasquinel the two bullets.

“They’re gold!” Pasquinel cried, letting them drop heavily into a cup.

McKeag interrogated the braves for nearly an hour, trying to determine how Lame Beaver could have obtained gold bullets, and in the end it was agreed that he must have located a lode. Where? No one knew. When? It must have been after the winter when the Arapaho helped cure McKeag’s shoulder, because that year there was no evidence of gold bullets.

“Where did he go that winter, after he left us?” Pasquinel asked.

“After buffalo,” McKeag answered. “Don’t you remember? They said, ‘We’ve got to find one more herd before winter’? That’s what they said.”

“Are there any mountains north of that river?” Pasquinel demanded.

The question was interpreted for the Pawnee, who answered, “No. Flat. Flat.”

Pasquinel became obsessed with Lame Beaver and his gold bullets. Somewhere this clever Indian had found gold. The trick now was to determine where. Guidance could come only from Blue Leaf; she would know where her husband had found his treasure, so during the forthcoming season they would seek her out and extract the secret. In the meantime, they would carry the two gold bullets to Saint Louis and sell them for the Pawnee.

Unfortunately, when he reached home, Pasquinel’s preoccupation with the bullets diverted his attention from the inventive work his wife had completed during his absence. Applying the funds he had left with her, plus others she had wheedled from her father, she had purchased a lot on the residential Rue des Granges. It commanded a comprehensive view of the town; it seemed above the river yet part of it. Here she had built a good stone house with a porch on four sides. The house contained many features suitable for dwelling along the edge of a German forest, yet its outward appearance was completely French, built only of such materials as a frontier town could provide. If a needed brick or fabric was unobtainable, she turned up some ingenious substitute.

And she was the major adornment of the house, a large, capable young woman with zest for whatever was happening in the world. If persons of importance passed through Saint Louis to the western frontier, she wanted to know them, to talk with them of their prospects. In the winter of 1804, for example, she entertained frequently for Captain Meriwether Lewis and his assistant, Lieutenant William Clark, as they prepared an expedition to explore the upper Missouri River, and perhaps points farther. But her special guest was Captain Amos Stoddard, who had been sent to Saint Louis by President Jefferson on a mission of peculiar delicacy. He and his aide, Lieutenant Prebble, made her house their virtual headquarters, and conversation was good.

Pasquinel fitted easily into such entertaining. He was a rough, convivial host, and what he lacked in social grace, he made up for with tales of his adventures on the prairie. Such guests as joined the parties liked to talk with him of Indians, and he expounded views which were more readily accepted by his French listeners than by Captain Stoddard and his aide. “I have one rule,” Pasquinel often said. “Never fight the Indian if you can avoid it. Never betray him in a trade. Bring him to you by faithfulness.”

It was remarkable that the French, who had followed these precepts in Canada, would enjoy three hundred years of amiable relations with their Indians, while the Americans, who were sure the ideas were wrong, would breed only agony with theirs. Perhaps it was because the French wanted trade; the Americans, land.

Lieutenant Prebble voiced the prevailing view: “We found in Kentucky—and everywhere else, for that matter—that the only reasonable way to handle an Indian is to kill him. Trust? He doesn’t know the meaning of the word. I say thank God there’s a wilderness out there where decent white men will never want to live. I say let’s throw every damned Indian into that desert and let them keep it till hell freezes.”

In February, after one such dinner, Lise told her husband and her father that she was pregnant, and they had a private celebration, to which they summoned McKeag, who was alone in his room. There was laughter and prediction as to what the boy would be, assuming, as Pasquinel did, that it would be a boy. Bockweiss suggested that he become a silversmith, to keep the profitable business going, and to everyone’s surprise, Pasquinel agreed. “Keep him in Saint Louis,” he said forcefully. “Never let him work the rivers.”

He himself spent the winter interrogating voyageurs as to where gold might be found, but none of them knew. He asked Captain Lewis, who said, “There’s no gold in America.” Lieutenant Prebble gave him a book on the subject, but of course, he couldn’t read.

On March 9 of that year Pasquinel and the other Frenchmen in Saint Louis watched approvingly as Captain Stoddard engineered a comical, warm-hearted charade. He had been ordered by President Jefferson to inaugurate United States rule in the sprawling Louisiana Purchase recently acquired from Napoleon of France. But there was a complication.

Since Spain had never got around to relinquishing control of the area to France, as she had been obligated to do by one of those treaties which periodically ended European wars, Saint Louis was still Spanish, and French authorities could not legally hand it over to America. It was Stoddard who devised the ingenious stratagem whereby everything could be set right.

“The top Spanish officer in the area must formally cede this domain to the top French officer in the area,” he suggested. “Then the French officials can, with propriety, yield the territory to the United States.” Few proposals in the brief history of Spain’s San Luis de Iluenses had been more enthusiastically received, and through the streets ran Pasquinel, shouting, “Tomorrow we shall all be French again.”

But there was another difficulty. In the entire area there was no Spanish official; strange as it may seem now, the only Spanish officer in the territory was Charles de Hault de Lassus, a French lieutenant who happened to be serving as the Spanish governor of Upper Louisiana, and if he was required to represent Spain in this transfer, where could a French officer be found to represent the Emperor Napoleon? Captain Stoddard was not only resourceful, but also gallant, and he volunteered to fill the breach: “For this one day I designate myself as the legal representative of his august majesty the Emperor of France, and on his exalted behalf I shall accept the transfer.”

So on the morning of March 9 a varied crowd surrounded the governor’s residence, a squat building on Rue de l’Eglise marked by a flagpole. First in attendance were the Indians assembled from four neighboring tribes to witness the celebration: Delaware, Shawnee, Abnaki, Sac. It was a cold day and they stood in buffalo robes, turning their heads sharply whenever cheers or guns exploded. Second came the French contingent, led by Captain Stoddard, eleven men, including Pasquinel, in Sunday clothes. Third were a few casual Americans, quite dirty and out of place. And finally there was Governor de Lassus, a Frenchman making believe he was a Spaniard in this gracious puppet play.

Very proper and grave, he stepped into the street as drums beat and fifes whistled. At his signal, the Spanish flag was slowly lowered while the battery on the hill thundered an eleven-gun salute. The ensign was folded and retired, with no one shedding a tear, since there were few Spaniards in town.

But now things changed. The new flag of France, Napoleon’s tricolor, was briskly unfurled, attached to the halyards and run up the pole. Many guns were fired and fifes played martial airs. Captain Stoddard, loyal emissary of Napoleon, accepted the transfer and led the French contingent in cheers, with Pasquinel tossing his red cap in the air, and for twenty-four glorious hours Saint Louis was again French.

That day and all that night Pasquinel toured his old haunts, declaring, “Je suis Français. Je serai toujours Français. A bas l’Amérique.” In the morning, bleary-eyed and sad, he invited half a dozen equally depressed Frenchmen to his home on Rue des Granges for breakfast, after which he trooped back to the governor’s residence and stood with tears in his eyes as De Lassus, once more a French lieutenant, turned the region over to Captain Stoddard, once again the loyal representative of President Jefferson.

Out of decency a member of the committee cried, “Three cheers for the United States!” but to his embarrassment no one responded. Pasquinel spoke for the citizenry when he said, “I’d like to cut my throat.”

That autumn, immediately after his son was born, he and McKeag set off for the Platte, with Pasquinel determined to find the Arapaho gold mine. Wherever they went, he asked for news of Lame Beaver’s family, but it was not until June of 1805 that they came upon a Cheyenne war party whose members knew what had happened.

“Blue Leaf is dead. Snow.”

“Dead!” Pasquinel erupted. “She was too young.”

“She’s dead.”

“The girl? Clay Basket?”

“We don’t know.”

It was here that Pasquinel announced a decision which gave McKeag his first intimation that ultimately there must be trouble in Saint Louis. The Frenchman said, “I’m not going back this summer. I’m going to stay here until I find that gold.” McKeag tried to argue that this was inhuman, seeing as how Lise had just had a baby, but Pasquinel replied brusquely, “Bockweiss will look after her. He’ll always look after her, that one.”

Accordingly, Pasquinel cached their pelts, his preoccupation with gold having prevented the partnership from accumulating more than two bales, then led the way over a wide scatter of abandoned campgrounds and empty river basins. The Arapaho seemed to be hiding, maliciously: they were not at Beaver Creek or at Rattlesnake Buttes or at that fine spot where the rivers met. Winter approached and the traders camped at some nondescript place, not even bothering to build a proper shelter.

They did not return to Saint Louis during all of 1805, wasting their time looking for the gold, but in April of 1806 a Ute war party passed on its way to steal horses from the Pawnee, and they advised him that as they came out of the mountains, they had seen signs that a band of Arapaho had moved into Blue Valley.

“Où est-ce?” Pasquinel asked with unconcealed agitation.

A Ute pointed toward the mountain up whose side climbed the stone beaver and said in sign, “Stream right, stream left.”

Pasquinel and McKeag first saw Blue Valley during an April storm. Rain swept in from the mountain and the area was covered with mist, but as they progressed the sun came out in explosive splendor, and they saw a compact meadow bisected by a stream of crystal water, with many aspen trees to the right and a mass of dark spruce to the left, each needle clean and shining.

“A place for gold,” Pasquinel said, but McKeag just looked. He saw the trees, the lovely sweep of the meadow and the myriad beaver lodges.

“We could trade here for years,” he said, but Pasquinel was not listening.

“This has to be where he found the gold,” he said.

They saw a modest trail leading into the heart of the valley and deduced correctly that this must be where the Ute war party had passed. Following it for about a mile, they saw farther ahead where the Arapaho were camped; running forward to identify himself, Pasquinel saw with delight that this was the band to which Lame Beaver had belonged. When they met the chief, they said they were sorry that Lame Beaver was dead.

“He staked himself out. He wanted to die.”

“Blue Leaf?”

“Her time to die.”

They asked where the Arapaho got their bullets, and the chief showed them a sheet of lead and his bullet mold. Pasquinel asked casually if he could see some of the bullets, and the chief summoned a squaw and commanded her to show the ones she had made that day. They were lead.

As Pasquinel hefted them, McKeag saw Clay Basket coming down the valley. She was now sixteen, tall, shy, but deeply interested when children cried that the white men had come back. When she saw them she stopped, smoothed down her elk-skin dress and adjusted the quills about her neck. Her black hair fell in two braids, and she seemed somewhat pale from the effects of winter, but she was even more bright-eyed than she had been as a child. Walking gravely to McKeag, she placed her hand softly on his right shoulder and asked in English, “Good?”

He thumped his shoulder and replied, “Good.” Pointing to Pasquinel, he said, “He fix.” He delighted the Indians by taking off his shirt and showing them the clever device that Pasquinel had fashioned from buffalo hide, a kind of armor which fitted over his damaged shoulder, enabling him to jam the rifle butt against the hardened hide and fire without fear of the kickback. Clay Basket touched the harness and approved.

May and June of that year were the happiest months Pasquinel, McKeag and Clay Basket had shared. The valley was superb, but the weather had grown so warm that passing Indians no longer had pelts. There was no specific reason for the white men to linger, but Pasquinel still did not know where the gold was, and he did not propose leaving until he found out. He became so attentive to Clay Basket that the Arapaho women, shrewd detectives where sex was concerned, deduced that although it was Pasquinel who had fallen in love with her, it was McKeag she had chosen for her mate.

They were confirmed in their judgment when a young brave who up to now had assumed that he would marry Clay Basket picked a fight with McKeag. It was settled when the Scotsman gave the young man a buffalo robe. Here was an opening for McKeag to pursue his suit, if he wished, but as the women had expected, he did nothing.

In midsummer Pasquinel asked one of the women, “What will Clay Basket do?”

“Difficult,” she replied. “Poor girl, she loves Red Beard.”

“Will she …”

The woman laughed. “Red Beard will never take a wife. Everybody knows that.”

“Then what?” Pasquinel asked.

Again she laughed. “Clay Basket will marry you. Next moon.”