IF IN THE YEAR 1844 A GROUP OF EXPERTS HAD BEEN COMMISSIONED to identify the three finest agricultural areas of the world, their first choice would probably have been that group of farms in the south of England, where the soil was hospitable, the climate secure and the general state of husbandry congenial. Here sturdy farmers, well versed in the ancient traditions of the countryside, raised Jersey cattle, plump black-and-white Hampshire hogs, rugged Clydesdales and poultry of the best breed.

The experts might also have selected that rare and rich band of black chernozem that stretched across southern Russia, especially in the Ukraine. Two feet deep, easy on the plow, and so fertile that it needed less than normal manuring, this extraordinary soil was unequaled and constituted an agricultural treasure which the serfs of the area had mined for the past thousand years without depleting it.

But whether the experts had chosen England or Russia, one area that would have had to be included was that fortunate farmland lying around the small city of Lancaster in southeastern Pennsylvania, at the eastern foothills of the Appalachians. For sheer elegance of land and profitability of farming, it stood supreme.

It was not flat land. There was just enough tilt to the meadows to prevent rain from gathering in the bottoms and turning the land sour. Nor was the topsoil unusually deep or easy to cultivate. If a man wanted to have a fine Lancaster farm, he had to work. But the rainfall was what it should be—about forty inches a year—and there was a change of seasons, with frosty autumns during which hickory nuts fell and snowy winters when the land slept.

The Lancaster farmer did not exaggerate when he boasted, “On this land a good man can grow anything except nutmeg.” And on all of it he could make a handsome profit, for his farm lay within marketing distance of Philadelphia and Baltimore. Corn, wheat, sorghum, hay, truck, tobacco and even flowers could be got to market, but it was the animals who prospered most and provided the best income, particularly cattle and hogs. Lancaster beef and pork were the standards of excellence against which others from less fortunate regions were judged.

In the divine lottery which matches men and soil—that chancy gamble which often places thrifty men on fields of granite and wastes good farms on incompetents content to reap whatever the wind sows—a proper match-up was made. Into Lancaster County, in the early years of the eighteenth century, came a body of well-trained peasant farmers fleeing oppression and starvation in Germany. Arriving mostly from the southern parts of that country, they brought with them a rigorous Lutheranism, which in its extremes manifested itself as the Amish or the Mennonite faith.

It was the Amish who determined the basic characteristics of Lancaster. They were an austere group who eschewed any display such as buttons or brightly colored clothes, and rejected any movement which might soften the harsh Old Testament pattern of their life. At the age of ten each Amish boy was married to the soil, and to it he dedicated the remainder of his life, rising at four, tending his chores before eating a gargantuan breakfast at seven, laboring till twelve, then eating an even larger meal which he called dinner. He worked till seven at night, ate a light evening meal called supper, after the tradition of Our Lord, and went to bed. He worshipped God on Sundays and in all he did, and when he was old enough to have a black buggy of his own and a brown mare to draw it, as he drove from Blue Ball to Intercourse, he would pause sometimes to give thanks that fate had directed him to Lancaster County, a land worthy of his efforts.

In most other parts of the world the Mennonites would have seemed impossibly rigid, but when compared to the Amish they were downright frivolous, for they indulged in minor worldly pleasures, were expert in conducting business and allowed their children other choices than farming. Some Mennonite children even went to school. But when they did farm, they did it with vigor and were wonderfully skilled in extracting from their soil its maximum yield. When this was accomplished, they became uncanny in their ability to peddle it at maximum profit. Mennonite women in particular were gifted at selling; they knew to the penny what they could demand of a customer, giving him in turn such a good bargain that he was likely to come back. Dressed in demure black jackets, black skirts, white aprons and white net caps, they were prepared to haggle a wagon driver into the ground and to extract the price they wanted, and if they lost a sale they grieved.

In January 1844 one of the most interesting spots in Lancaster County was the rural village of Lampeter. It had been named after a profane and riotous wagoner called Lame Peter who had used that particular spot as a depot when freighting farm produce to Philadelphia. In time all wagoners adopted the custom of laying over in Lampeter, and since they were a rough lot, the main thoroughfare of the village, with Conestogas hitched to every tree, became known as Hell Street.

“Meet you in Hell Street with bells on!” wagoners shouted as they departed Philadelphia on their way home, and when the long canvas-covered wagons jingled into Hell Street, pulled by six dappled horses, each with its canopy of bells—five on the first pair of horses, four on the second pair, three on the third pair—the street echoed with jollity. Many girls who had been leading drab lives on farms in other parts of the county gravitated to the inns that lined Hell Street to listen for the bells of the incoming wagoners.

On a Thursday afternoon, January fourth, a disgruntled wagoner approached Hell Street in silence. His horses lacked the twenty-four brass bells which a proper team of Conestogas should have, and loungers at the inn came into the street to mark this strange arrival. “He lost his bells!” one of the girls cried, and soon customers had left the bars to stand in the snow around the unhappy wagoner.

“How’ja lose yer bells, Amos?” a fellow teamster shouted.

“That damned left rear,” Amos replied, tying his lead horse to a tree. “Started to work loose east of Coatesville. Had to be pulled out.”

The Conestoga wagoning fraternity had strict rules: if a teamster got himself into such a predicament that he required help from another, he was obligated to give his rescuer a set of bells. This was the ultimate humiliation.

“You gettin’ another set of bells?” an innkeeper asked as Amos moved away from his horses.

“That I ain’t,” Amos growled. He was a tall, angular man with a mean scowl.

“You quittin’?”

“That I am,” he replied, and with this he rushed back to the offending Conestoga and began kicking the left rear wheel, at the same time shouting such curses as even Lampeter had not heard for some time. He grew purple in the face, throwing the vilest words he could think of until it seemed that he must scorch the canvas. With a final mighty kick he tried to knock the wheel into the next county, then stood with his arms folded, staring at the wagon and uttering a summary curse that repeated no single profanity but required a minute to discharge. Then, flinging his arms wide and surveying the crowd, “Anybody can have this bullshit wagon. I never want to see it again.” With that he stomped into the White Swan.

At the edge of the crowd, stamping his feet to keep warm while he watched this remarkable performance, stood a young Mennonite in black suit and flat-brimmed hat. He was twenty-four years old, stockily built, with a reddish beard that started at his ears and met in a neat line just at the edge of his chin. Since his face was already square, the fringe of beard made it look as if it had been framed.

Casually he inspected the abandoned Conestoga. It was old; he could see that. “Probably been used for forty years,” a farmer near him judged. “The paint’s wore somethin’ awful.” The original deep blue of the box had faded to a pastel, while the bright red of the wheels and tongue had become gray-orange. “That left wheel don’t look much,” the farmer said, kicking at it several times. “Lissen to it rattle.”

As they looked at the worn old wagon a tardy arrival from Philadelphia pulled his Conestoga into Hell Street. With one swift glance he perceived what had happened to his associate. “My God! Amos Boemer lost his bells,” he shouted, and a crowd left the White Swan to greet him.

“Jacob Dietz had to haul him out of a drift,” one of the crowd explained. “East of Coatesville.”

The new arrival walked around the old Conestoga, kicked at the wheel and said, “Told him he should get a new one. Told him last month.”

“Wagon’s for sale. If’n you want it.”

“Me? Want a used-up Conestoga?” He laughed and led the way into the White Swan.

The young man with the square beard was left alone in the snowy road. Moving slowly, he walked around the Conestoga, judging its condition, then started for home. He was headed east of town toward one of the finest farms in Lancaster County, just beyond the tollgate. It stood to the south of the road, down a lane marked by handsome trees, now bare of leaves.

From a long distance the stately stone barn—with its red-and-yellow hex signs to ward off evil—was visible, and in the cold moonlight the young man could see the proud name worked into the masonry:

JACOB ZENDT

1713

BUTCHER

As with any self-respecting Lancaster farm, the barn was six times the size of the house, for Amish and Mennonite farmers understood priorities.

As the young man walked down the frozen lane, his heavy shoes making the snow crackle, his attention focused mainly on the trees. Because hickory and oak were so vital in his business, he could spot even a young hickory at a hundred yards, marking it in his mind against the day when it would be old enough for him to harvest.

The Zendt farm contained many fine trees: there was the perpetual woods first harvested in 1701 when Melchior Zendt arrived from Germany; then there was the line of trees along the lane, planted by his son Jacob in 1714, and best of all, there was the miniature forest set out by Lucas Zendt in 1767. It rimmed the far end of the pond and was as fine a collection of maple, ash, elm, oak and hickory as Lancaster County provided. Each tree on the Zendt farm was a masterpiece, properly placed and flourishing.

When he reached the farm buildings, the young man looked briefly at the huge barn, then at the small red building in which he worked, then at the even smaller one stained black from much smoke, then at the various snow-covered pigsties, chicken coops and corncribs. Finally, tucked in among the larger buildings, there was the house, a small clapboard affair. There was a light in the kitchen window, and pushing open the door, he saw that his mother was preparing supper while his oldest brother, Mahlon, read the Bible.

“Amos Boemer lost his bells,” he announced as he hung up his hat. “He cursed somethin’ awful.” His mother continued working and Mahlon kept to his Bible.

“I never heard cursin’ like that before,” the young man continued.

“God will attend to him,” Mahlon said in a deep voice, without looking up from his Bible.

“Got into a snowdrift east of Coatesville,” the young man said. There being no response, he went to the washstand and prepared for supper.

But as he washed his face Mahlon observed, “Amos Boemer is a blasphemous man. Little wonder God struck him down.”

“It was the left rear wheel.”

“It was the will of God,” Mahlon explained.

Now his mother lifted a heavy bell, ringing it for half a minute until the whole farm filled with sound. From the big barn came Christian, whose job it was to purchase hogs and cattle from surrounding farmers; on his ability to buy cheap at the right time depended the financial success of the family. From the pigsties came Jacob; it was his responsibility to see that there was a steady supply of pork. From a clean white building came Caspar; he did the butchering. Levi, the youngest brother, who had watched the arrival of the Conestogas, worked in the two smallest buildings, the red and the one stained black; his job was to make sausage and scrapple, and at this he was so proficient that Zendt pork products brought the highest prices in Lancaster. There was even talk of shipping them in to Philadelphia when the railroad was completed to Lancaster.

The four younger brothers, each with the stamp of Mennonite upbringing, took their places at the two sides of the long table. Their mother, now in her sixties, sat at the end nearest the stove so that she could attend to such cooking as continued during the meal, and at the other sat the oldest brother, Mahlon, a dark and gloomy man in his thirties, feeling the responsibility for this family now that the father was dead.

When the six were seated, they bowed their heads for grace while Mahlon reviewed the evil state of the world and asked for forgiveness for such sins as his four younger brothers had committed during the interval since dinner: “We are mindful of the fact that Brother Levi has been spending his afternoons on Hell Street, consorting in taverns and making acquaintances with the devil. Guide him to halt this infamous behavior and direct him to attend to his proper obligations.” Levi flushed and could feel the others looking at him from beneath lowered foreheads.

Mahlon had a long list of matters he desired God to take notice of, and at the end he repeated the rubric which had guided this family for the past hundred and fifty years: “Help us so to live in Thy light that our name shall be respectable in all its doings.” From the five listeners rose a fervent “Amen.”

It was curious that this supper table contained only one woman. Each of The Five Zendts, as they were called in Lancaster, was of marriageable age and each could be considered a catch. Many farm girls watched the Zendts, especially the four oldest; there was some talk that young Levi was not too stable.

But the Zendt family had always married late, when the stormy passions of youth had been suppressed and when the family as a whole had time to study contiguous farms to ascertain which had desirable fields that might accompany the girl of the family when she married. The Zendt farm had started with sixty acres in 1701 and now contained somewhat over three hundred, and you didn’t augment a farm that way by marrying the first girl who came along when you were twenty. You did it by patient acquisition, and if fate determined that you must marry a girl who lived in another part of the county, you sold off her dowry immediately and bought land touching yours. In 1844 there was no better farm in Lancaster County than the Zendts’, and with five marriageable sons, by 1854 it ought to be much better.

Mahlon, at thirty-three, had begun slowly to focus upon a certain girl who was likely to receive a substantial amount of land when her father died. He hadn’t divulged his decision to anyone yet, least of all to the girl, because a man didn’t want to rush into these things, but he kept his eye on her.

Tomorrow was Friday, the last of the three big days around which the Mennonite week revolved: Sunday for worship; Tuesday and Friday for market. At the conclusion of supper Levi shoved back his chair, saying brusquely, “I’m goin’ out to see the souse,” and when he was safely gone Mahlon told his brothers, “We must all watch Levi. He’s getting feisty.” The three other Zendts agreed. In their earlier days each of them had gone feisty at some time or other, had wanted to smoke tobacco, or taste beer at taverns along Hell Street, or ogle the girls, but each had suppressed these urges and had stuck to butchering. It was clear that now they would have to guide Levi through this dangerous period.

Out in the yard he lit a lantern and walked stolidly across the frozen snow to the small red building. Kicking open the door, he surveyed his little kingdom and found it in good order. The sausage machine was clean and placed against the wall. Six baskets of white sausage links were lined up and waiting. The twenty large flat scrapple pans were stacked, each filled nearly to the brim with a grayish delicacy hidden beneath a protecting layer of rich yellow fat. It, too, was ready. It was the souse that needed attention, and when he saw it still on the stove, he knew that he should have worked that afternoon instead of wandering down to Hell Street to watch the wagoners roar in.

Levi liked souse better than any of the other products he made, and he devoted extra attention to preparing it. Throughout the Lancaster area it was said, “For souse, Levi Zendt.”

He went to the stove and dipped a long-handled ladle into the simmering pot. The thirty-six pigs’ feet looked done. He picked up a bone from the ladle, and the well-cooked meat slid off.

“Good!” he said.

He lifted the kettle from the stove and with great skill extracted all the white bones of the hogs’ feet, being careful to leave in the gristle, for that was what made Zendt souse so delectable. He then returned the kettle of hog meat to the fire, tossing in six pounds of the best lean pork, well chopped, and six hogs’ tongues, also chopped. Throwing two chunks of wood into the stove, he allowed the mixture to cook while he prepared the broth which gave the souse its taste.

Extracting stock from the bubbling kettle, he poured it into a large crock to which he added twelve cups of the sourest cider vinegar the area could provide. “That’ll make ’em pucker,” he said. He then added twelve tablespoons of salt to give the souse a bite, three teaspoons of pepper to make it snap, and a handful of cloves and cinnamon bark to make it sweet. He placed the crock on the back of the stove, keeping it warm rather than hot. Twice he tasted it, smacking his lips over the acrid bite the vinegar and salt imparted, but he crushed two more cloves to give it better balance.

He now laid out twelve souse pans and placed in each of them round disks of the sourest Lancaster pickles and here and there a single small slice of pickled carrot. Then like an artist he adjusted various items to produce a more pleasing design.

After a few minutes he took the kettle of bubbling meat from the fire and with tongs began fishing out the larger pieces of meat, arranging them among the pickles and carrots in the bottom of the pans. It was here that Zendt souse achieved its visual distinction, because the meat came in two colors, white chunks from the fatty parts, red meat from the lean; he kept the two in balance, working rapidly, pulling up smaller and smaller pieces and distributing them evenly.

Finally, when little meat was left, he tipped the crock forward and strained the broth through a sieve, which removed the cloves and bits of cinnamon bark.

“Good!” he grunted.

With care he ladled the broth into the pans of meat, and he had calculated so neatly that when the last pan was filled, the kettle was empty. Before he had finished cleaning up, the gelatin from the hogs’ feet had begun to set. By morning the souse would be shimmering hard, filled with tender pork and chewy gristle, clean and sour-tasting.

Links of sausage, pans of scrapple, flats of souse, that’s what the people of Lancaster expected from the five Zendts and that’s what they got.

When he left the red building he poked his lantern into the small black building, where a flood of acrid smoke greeted him. Covering his nose, he looked up at the rafters where great sausage links hung suspended, brown from the penetrating hickory fumes. They looked just right, but nevertheless he squeezed an end to satisfy himself. It was hard and firm, with just a little grease running out. He smelled it. A strong aroma of burnt hickory, one of the most enticing smells in the world, reassured him.

“It’s ready,” he announced to his brothers as he rejoined them.

“We expected it to be,” Mahlon said. He had the Bible open and now asked his four brothers and his mother to join him in their nightly prayer. This being Thursday night, he intoned: “And help us, O Lord, to be honest men tomorrow and to give good measure and to behave ourselves as Thou wouldst have us, and may no one who comes to us feel cheated or robbed or in any way set upon.” It was a prayer his father had uttered when the boys were young, and his father before him.

Closing the Bible reverently, he said, “Breakfast at three, Momma,” and the five Zendts went to bed.

Friday for Levi was a day of joy. It was the end of the week and people coming to the market were apt to be in a happy mood, and the Stoltzfus bakery … In bed he hugged himself. He could visualize the double stall of the Stoltzfus bakery.

At three the heavy bell rang and the five boys came down to the hearty breakfast their mother had started preparing at two. Scrapple and sausage, a little smoked bacon and some pig’s liver and fried chicken, eighteen fried eggs with slabs of ham, some good German bread and two kinds of fruit pie, dried apple and canned cherry, and quarts of milk … that was the market-day breakfast for the Zendts.

After morning prayers they all crammed themselves full, for their work was hard and generated tremendous appetites, and when they had pushed themselves away from the table Mahlon said, “I see that Levi’s sleigh isn’t loaded yet.”

“I was waitin’ for the souse to harden,” Levi said.

“If it had been made on time, it would be hardened, yet,” Mahlon snapped.

“It’ll be loaded,” Levi said briskly. He would not allow Mahlon to spoil his Friday.

Harnessing his two gray-speckled horses, he brought his sleigh to the small red building and there he gently lifted the various pans and baskets, placing them just so in the sleigh. He then ran to the smokehouse and pulled down the long links of smoked sausage and scooped up four dozen fine smoked porkchops. These, too, he placed in the sleigh, then shouted, “Christian! Caspar! We’re off.”

The three stout brothers drove their sleigh in behind the one containing Mahlon and Jacob, and the procession started down the family lane, beneath the fine trees planted by Grandfather Lucas, and out onto the turnpike leading to Lampeter and on to Lancaster. At the tollhouse a grumbling old man appeared to collect the two pennies, after which Levi whipped up his horses and the Zendt boys were on their way to market.

As they drove down the silent white road they overtook other thrifty farmers on their way to market too. There were the Zuber brothers, noted for the vegetables they grew and the crocheted work their wives did. Coming down a lane west of Lampeter were the Mussers, the three women of the family in black dresses topped by delicate white caps of the filmiest net. They sold preserved goods, none better. The Schertzes and the Dinkelochers and the Eshelmans all fell into line, forming a caravan as rich as any that had ever crossed the sands of Persia, for they were taking to market the best that Lancaster County provided, and that had to be the best that the world produced at that time.

Through the darkness they went. It would take more than two hours to reach the center of Lancaster and the prudent farmers did not hurry their horses; they had no desire to jostle their produce or bruise it.

As day was beginning to break, the sleighs approached the town itself and entered the streets that soon would be filled with customers. But now they were still asleep and the sleighs passed the silent shops of Melchior Fordney the gunsmith, Caspar Metzgar the tailor, Philip Schaum the tinsmith and George Doersch, who worked in leather and bound books. Everyone in Lancaster was known by the work he did. Even two gentlemen who slept late that day had their proper signs out: Thaddeus Stevens, attorney; James Buchanan, lawyer.

Now the caravans began to break up. Smaller merchants, like the Musser women and the Eshelmans, who dealt in poultry, stopped before reaching the center of town and backed their sleighs against the open curb. There, along with scores of others from north and south, they would stand all day in the cold, selling to whoever came down the street.

Important merchants, like Zendt the butcher and Stoltzfus the baker, would ignore the curb sites and proceed directly to a cavernous, exciting building, where they would spread their wares. Only the most prosperous could afford to pay the rent for indoor stall space, the established farmers from Rohrerstown and Landisville and Fertility.

The five Zendts drove their two sleighs to the rear of the market, where the younger brothers began unloading while Mahlon and Christian hurried inside to arrange the stall in the clean, attractive way the Zendts had done for generations. The two brothers washed their hands and put on white coats; then they slipped on raffia wrist covers, and they were ready. With long-practiced skill they laid out the meats: the good steaks, the slabs of pork, the chopped beef, and inside a glass case the scrapple, golden yellow where the grease stood, rich meaty gray below, the sausage smoked or plain, and the trays of glistening souse.

As Levi lugged in his trays, his eyes kept hopping over the double stand opposite the Zendt location. There Peter Stoltzfus was opening a family stall which had almost as long a history as the Zendts’. Three generations had created a reputation for fruit pies and stollen, lebkuchen and shoo-fly and the best crunchy bread in the area. Stoltzfus himself was laying out large trays of gingersnaps and sugar cookies, enticingly arranged, and he waved a greeting to Levi.

“Spring’s comin’ yet,” he called.

“Good mornin’, Mr. Stoltzfus,” Levi replied. He was not really interested in the baker, but he deemed it prudent to keep on good terms with him.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the market scores of families were hauling in the myriad things that would soon be sold: large brown eggs, twelve cents a dozen; butter a deep yellow imprinted into blocks marked with flowers, nineteen cents a pound; apples of all varieties brought up from cold cellars, eighteen cents a peck; plucked chicken killed after midnight, twenty-four cents each; potatoes of the best variety, fifteen cents a peck; the largest turkeys, live and handsome, eighty-five cents; smaller turkeys, forty cents; lovely crocheted bedspreads, one dollar; a bucket of flowers grown indoors, twenty cents.

At Stoltzfus the baker’s, prices were slightly higher than at lesser shops, because his reputation was the best: a large mince pie, eighteen cents; a loaf of dark German bread, heavy and crusty, eight cents; gingersnaps with a real bite, three for a penny; chewy black-walnut cookies, ten for twelve cents; a three-tiered cake with lemon icing, twenty-five cents. And with every purchase a smile and a repeated thank you.

The Five Zendts kept their prices on the high side too. Their beef sold for five cents a pound, whereas at cheaper shops it could be bought for four or even three. Pork was a little higher, six cents a pound for unsmoked, seven cents for smoked, but it could be bought elsewhere for four cents. The three specialties that young Levi made were much prized by the Lancaster housewives: scrapple at five cents a pound, sausage at six, and a generous square of souse at four cents. On these prices the thrifty farmers of Lancaster County grew rich.

It was three minutes to seven, and soon the market would be jammed with eager housewives. Levi, hauling in a keg of pickled pigs’ feet, looked across at the bakery, and to his dismay, only Peter Stoltzfus stood behind the polished counter. Then the drapes at the rear parted and she appeared.

It was Rebecca Stoltzfus, eighteen years old and a dark, lovely girl. She had a breathtaking complexion and jet hair which she parted in the middle and wore in two braids over her shoulders. She had deep-set eyes and a firm chin. She wore a dark-brown blouse, pulled in tight at the waist, above a sweeping black skirt and black buttoned shoes. Like most Mennonite women, she wore a white apron and a lacy network cap with two strings hanging down over her shoulders; on hers the strings were white, signifying that she was not married. She had a distinct cupid’s-bow mouth which made her especially attractive, for it gave her the kind of pout that made men look twice. Her father appreciated the fact that in Rebecca he had an asset which would be perpetually helpful in his business, and he showed her off to best advantage.

Levi, hoisting the keg of pigs’ feet into position, felt his mouth go dry. During the past week he had been thinking of little but the Stoltzfus girl; in reality she was even more delectable than in his dreams. He tried to nod, but she was preparing the counter for the rush that now descended upon it.

The citizens of Lancaster swarmed into the market as if food were their sole preoccupation, which in a way it was, for no other region on earth ate as well as the Germans of this county. In the overloaded stalls they could find a hundred varieties of food from Kleinschmidt’s walnuts to Moyer’s apple butter to Hauser’s crisp celery, kept in the icehouse since last September. Special favorites were yellow noodles so thick you had to chew them and jars of crisp pickles.

Levi Zendt helped his brothers haul in replacements as Mahlon and Christian handed out wrapped packages. A housewife from Fertility stopped Levi and told him in a heavy German accent, “I always feel better when I buy from your brother Mahlon. He don’t use no air pump to make his meat look better’n it is. He sells chust as God made it.” She nodded her head knowingly at the stall of another merchant who had the habit of inserting a pump nozzle into his stale meat, injecting it with air to make it look firmer, then sealing the hole with tallow.

“Mahlon wouldn’t do that,” Levi assured her.

“I know,” she said warmly. She placed her hand on Levi’s and said, “God will look after honest men.” Levi thanked her and continued with his work.

The Zendts did deal honestly. Strict Mahlon would see the business perish before he would pump air into meat or chop old beef and sell it as new. He tested his scales as carefully as St. Peter is supposed to test his when weighing souls, and if he threw in no added chunks, as some butchers did, he took none away either.

As Levi worked, he kept his eye on the Stoltzfus bakery stall, and the wonderful manner in which Rebecca moved and smiled as she waited on customers created new excitement in his heart. He could scarcely wait till the noon bell rang.

It had been his custom, for as long as he had worked in the market, to have a simple dinner. His mother always packed two slices of dark German bread and gave him a hefty helping of cup cheese to go with it. He cut off a cube of his own souse, and from the Yoder stall he bought three cents’ worth of pudding. At the Stoltzfus bakery he always purchased two cents’ worth of cookies, and it was then that he had a precious chance to say a few words to Rebecca.

For the last three weeks he had been planning a bold move, to ask her to eat her dinner with him, and now as twelve approached he got everything in readiness. At the Yoder stall he studied the enticing array of puddings: creamy rice pudding with raisins, good chewy bread pudding, cherry pudding with toasted crumbs on top and a delicious apple pudding rich with cinnamon.

“So today what?” Mrs. Yoder asked.

“Cherry,” Levi said, and she dished him out a most generous helping, providing a glass dish and a spoon which he would later return.

He then moved to the Stoltzfus stall, but was dismayed when Peter Stoltzfus stepped forward to wait on him. After a moment of panic Levi said, “I wanted to see Rebecca.”

“Becky!” Stoltzfus shouted so everyone could hear. “Levi Zendt to see you.”

With a gentle flowing movement that melted Levi’s heart, she left her end of the counter and came down to wait on him, the strings of her cap framing her beautiful face. “Today, gingersnaps?” He nodded and she counted them out.

He pushed his pennies toward her and gulped, “Rebecca, how about dinner with me today?”

She looked up brightly, as if she had been expecting just such an invitation, and smiled so that all her teeth showed. “Yes!” she said. “Wait’ll I fetch my coat.”

She disappeared for a moment, then called to him from a rear exit. He would have preferred slipping out the back entrance, but without his being aware of what she was doing, she maneuvered so that he had to take her directly past the Zendt stall. There, behind the counter, stood Mahlon, staring darkly at his younger brother. Levi did not see this, for he was stumbling along, trying to avoid the sly looks of keepers in the other stalls.

They went out into the snowy town and found a bench by the courthouse. For as far as they could see, the streets of Lancaster were filled with sleighs backed into the curbs, and Rebecca said, “It’s lucky our stalls are inside. Much warmer, eh!” He nodded.

Then she saw his food, that strange combination of souse and cup cheese, and she was about to comment on it when he said, “You ever tasted my mother’s cup cheese? Best in Lancaster.”

Taking a corner of his black bread, he spread it copiously with a yellowish viscous substance that one would not normally identify as cheese; it was more like a very thick, very cold molasses, and it had a horrific smell. Rebecca was not fond of cup cheese; it was a taste that men seemed to prefer.

“Poppa likes cup cheese,” she said with a neutral look on her pretty face.

“You don’t?” Levi asked.

“Too smelly.”

“That’s the good part.” He put the piece of bread to his nose, inhaling deeply. He knew of few things in the world he liked better than the smell of his mother’s cup cheese. By some old accident the German farmers of Lancaster County had devised a simple way of making a cheese that smelled stronger than limburger and tasted better. He ate her piece, his own, what was left and then licked the container. When he got to his cherry pudding, he offered Rebecca some, and this she accepted.

“Amos Boemer lost his bells yesterday,” he said as they finished.

“He did?”

“He cursed like I never heard before.”

“Maybe that’s why he lost them.”

“No. Snowdrift east of Coatesville.” He called it Coates-will.

Rebecca was obviously bored with the dinner, and after a little desultory conversation, said, “I must get back to help Poppa.” Patting him on the arm in a way that sent shivers through his whole body, she pirouetted away. When she reentered the market, she brought herself to Mahlon’s attention again, smiling at him more directly than a mere greeting would have required.

When Levi got back to the stall, Mahlon was dark with rage and would not even allow him to wait on customers while he, Mahlon, had his dinner. Levi, unable to guess what had gone wrong, went back to the sleighs and talked with the brothers working there.

At the end of the day, in accordance with a custom long observed by the Zendts, Mahlon and Christian set aside those bits of meat they would not be taking home, and these they chucked into baskets for the orphan asylum. When the market closed at five, these baskets were placed in Levi’s sleigh and it was his job to deliver them, while the other four brothers rode home together.

But this night, as the sleighs left, Rebecca Stoltzfus impetuously broke away from her father and jumped in with Levi. “I’ll help you deliver the gifts,” she cried, and Levi, in a state of euphoria, drove her past his startled brothers.

They rode out to the edge of town, to the orphanage supported by the women of St. James’ Episcopal Church; there he found the mistress waiting for him, attended by the girl-of-all-duties, Elly Zahm, who was directed to take the baskets into the kitchen.

“I’ll help,” Levi suggested, but the mistress would not allow this.

“You’ve done enough, bringing the meat. Elly can lug it.”

As the sleigh was leaving the orphanage to enter upon the dark street leading back into town, something happened that Levi Zendt would never comprehend as long as he lived. The nearness of this friendly and beautiful girl and the fact that she had chosen to ride in his sleigh got possession of him, and he started to wrestle with her, trying to steal a kiss. He was rough and awkward, and when she coyly pushed him away, he tore her dress. It was an appalling performance, and she began to scream and leaped from the sleigh. Girls from the orphanage, hearing her cries, ran out to see what had happened.

She fell sobbing into the arms of Elly Zahm. “He’s awful!” she whimpered. Then she managed to faint.

By Saturday morning the news had spread throughout Lancaster and had made its way to Lampeter and along Hell Street to the Zendt farm. When Mahlon heard it he had to sit down. He could not believe that a brother of his … He felt sick. Then, in a towering rage, he went to the door and screamed, “Levi! Come here!”

All morning young Levi had been expecting such a summons. He had fled deep into the smokehouse, attending to the dirtiest work on the farm, cleaning out the flues, hoping thus to escape attention. Pretending not to hear, he continued to work furiously, but soon the door to the house was jerked open and Mahlon’s wild voice shouted, “Come out, you son of the devil!”

In an agony of shame Levi crept slowly down from the flues and along the lines of curing hams and sausages. When Mahlon saw him, black as the fiends of hell, the older brother made as if to strike him, but Levi, anticipating this, grabbed a heavy bar used for moving hams, and brandished it.

“He’s gone crazy!” Mahlon shouted. “He’s attacking me.”

“I’m not,” Levi said stolidly. “You’re attackin’ me.” But he kept hold of the bar.

The other three Zendts ran up and disarmed Levi. They pulled him into the kitchen and forced him into a chair. Standing around him like a congregation of Old Testament judges, their beards giving them a look of great dignity, they waited for Mahlon to speak.

“You pig!” he roared, thrusting his face into Levi’s. “You child of the devil.”

Levi did not consider himself either a pig or a son of Satan. He was a young man caught up in feistiness, and even though he was confused, he understood that Rebecca Stoltzfus would not have climbed into his sleigh if she had not wanted to. It was in this moment of stubborn confusion that Levi Zendt, twenty-four years old, decided that he would not allow his brothers to bully him.

“I did nothin’ evil,” he protested.

That he would dare to argue back when he had obviously done something very evil enraged his brothers, and they closed in upon him so menacingly that their mother started to object: “Now boys! If Levi says …”

“Stay out of this, Momma!” Mahlon warned, and he indicated that Jacob should take the old lady from the kitchen.

When Jacob returned, the four brothers hammered at Levi in unison—shouting that he had taken leave of his senses, that he had humiliated them, disgraced the family name. “Everyone in Lancaster’s talking about it,” Jacob said bitterly.

For some strange reason Levi replied, “You haven’t been to Lancaster. I saw you workin’…”

The introduction of logic into such a situation infuriated the Zendts, and burly Caspar charged closer as if to strike his brother, but an anguished cry from Mahlon diverted him. “Didn’t you know,” he asked his youngest brother, “that I was planning to speak to the Stoltzfus girl myself?”

Levi looked up to see his tall brother’s face contorted with shame and anger and hatred, and the younger man began to realize what had happened. Mahlon, thirty-three years old, had finally settled on a girl of good family and with substantial land holdings, but being a cautious man, he had not wanted to commit himself precipitately. He had therefore merely indicated his intentions to the girl, then drawn back … to study, to reconsider all angles. And the girl had grown impatient and had used Levi to stir the pot. How well she had succeeded.

“Mahlon was intending to ask the Stoltzfus girl,” Christian explained, in case that fact had escaped the culprit, and in the next half hour each of the brothers repeated that a great wrong had been done Mahlon, the head of the family. No one ever called the girl Rebecca. To them she was merely the Stoltzfus girl, the property of Stoltzfus the baker and heiress to the Stoltzfus acres.

Finally Mahlon handed down the verdict: “You can never work at the market again, that’s clear. You stay here and tend your duties and at the end of the day you come into the market and clean up.”

“How’ll I get in?” Levi asked, always the practical one.

“You’ll walk,” Mahlon said. “We’ll leave you a sleigh for the cleaning up.”

“You were a disgrace to the family,” Christian said bitterly.

Then Mahlon added, “And on Tuesday you’ll ride in with me and you’ll apologize to Peter Stoltzfus … and the Stoltzfus girl. Where everybody can see.”

Now Levi dropped his face in his hands, mumbling, “I don’t want to go back.”

“I’m sure you don’t,” Mahlon shouted, his pride burning, “but it’s the only way this family can redeem itself. Your apology to the whole market.”

That first Saturday was hell. Levi returned to the smokehouse, finding both refuge and consolation in its murky depths. With studied care he picked the choice pieces of hickory, placing them individually on the smoldering fire and allowing the smoke to pass over him as if it could purify him of the heavy stain he bore.

At dinner he could not face his brothers again; he walked alone through the grove of leafless trees and muttered to himself, “This is the only place that makes any sense.” Then he visualized himself apologizing to Peter Stoltzfus while Rebecca looked on, and he was so smothered in shame, it seemed to him that even the trees turned away from him.

In the afternoon his mother came out to the sausage machine, bringing a jar of cup cheese and some bread. She told him, “Mahlon’s awful hurt. You must forgive him.”

Without relishing it, he slowly ate the cup cheese, licking it off his fingers and listening as his mother said, “It don’t matter, what happened with the Stoltzfus girl. I knew she was a little flirt the first time I met her. Peter Stoltzfus spoils her crazy, and I hope Mahlon don’t marry her. Maybe you done us all a good.”

Sunday was worse. His brothers insisted that he attend church, to let the community view his disgrace, and he had to tag along, sitting in the family pew and feeling the hot stares of the Mennonites, each of whom had heard of what was now being called his assault on the Stoltzfus girl.

“Rape,” a father whispered to his daughters in the row behind. “The work of the devil here in Lampeter.”

At the close of service he had to run the gantlet of condemnatory glances as Mahlon and Christian paused to explain in loud voices that the whole family was ashamed of what had happened—mortified, Mahlon said—and that Levi was going to apologize to the Stoltzfus girl and her father on Tuesday.

The ugly part came at dinner, when Reverend Fenstermacher and his acidulous wife, Bertha, appeared at the Zendt kitchen for their customary free meal. The minister was considerate enough to say to Mahlon, “I know I’m expected at dinner, but in view of the tragedy that’s overtaken your family, perhaps …” He hoped with all his heart that Mahlon would not cancel the invitation.

And Mahlon said, “You must come! Maybe you can throw some light into his dark soul.” This pleased the Fenstermachers enormously, because they knew how good Mrs. Zendt’s cooking was.

In Lampeter the Zendts were known as one of the typical merchant families that kept the best for the market and served the nubbins at home. In a sense this was true. Mahlon never handed his mother any choice piece of beef or the best apples from the orchard; they were reserved for the families of James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens. Mrs. Zendt got only the second or third best for family use, but she was such an exceptional cook that from nubbins she produced better results than others did with the best. And when the preacher came, she outdid herself.

It was a splendid board she laid that day. Both the table and the stands along the wall were jammed with the best German dishes. She had never subscribed to the old rule that a table must contain seven sweets and seven sours, but she did believe in a generous variety. For meats she had beef pot roast and frizzled dried-beef gravy, pork loin and leftovers from the last ham. For fowl she had a delicious roast hen and a rooster boiled for many hours and served with dumplings. For vegetables she had whipped white potatoes and candied yams, tomatoes and peas, scallions grown indoors, and lettuce with hot bacon dressing. She had five kinds of sours: onions, red-beet eggs, pepper cabbage, chow-chow and plain cucumber. She had four kinds of sweets: applesauce rich and brown, pickled pears, canned peaches and a rich cherry preserve. To start with she had soup with rivels, of course, three kinds of bread, and to close the meal four pies: apple, cherry, lemon meringue and wet-bottom shoo-fly, Mrs. Zendt’s specialty made with molasses and cinnamon bread crumbs.

Reverend Fenstermacher, surveying the feast with long-practiced eye, noticed that she had no cake.

When the eight were seated, Mahlon looked to the preacher, and Reverend Fenstermacher was ready. He had been pondering all day what he ought to say when he dined with the Zendts, and his mind was clear. Surveying the bowed heads, he cried in strong German, “O Lord, we have within our midst this day a sinner, a most grievous sinner, a man who has descended to the level of the beasts, nay, lower.”

That was the opening. From there he reviewed Levi Zendt’s pious upbringing, the sterling character of his father and his mother, who, praise God, was still with us this day, and especially his Grandfather Zendt, who would be suffering tortures in heaven as he contemplated the disgrace brought upon his family by his grandson, Levi. Reverend Fenstermacher pronounced it Lee-wy, and it was repeated several times until it did sound like the name of a depraved man.

In the midst of his discourse Reverend Fenstermacher used a provocative phrase: he said, “A man like this should go and live amongst the savages.” The prayer ended on a hopeful note, Reverend Fenstermacher thought, for he did hold out reassurance of salvation if Leewy spent the next forty years of his life in dutiful repentance, as he, Fenstermacher, was convinced he would.

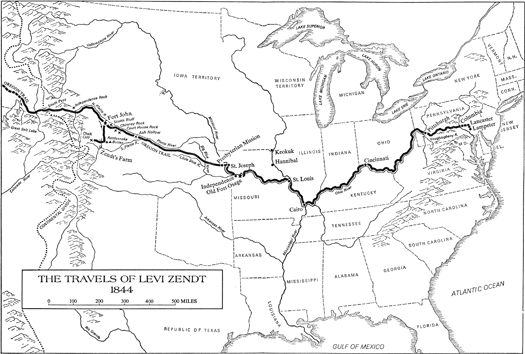

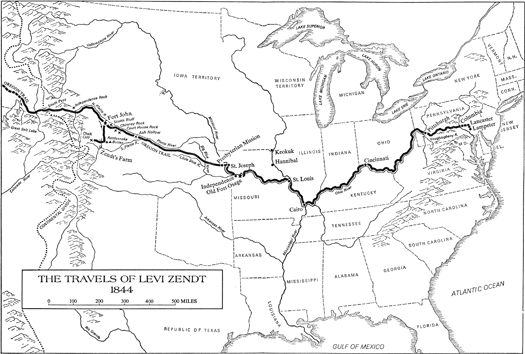

All Levi remembered of the prayer was the part about going and living amongst savages, and while the others ate voraciously, he kept his square, stubborn face looking down, refusing food, and thinking of a name he had recently learned: Oregon. At the market one day he had heard men from Massachusetts talking; they had traveled all the way to Lancaster to purchase two wagons. They had said, “We’re heading for Oregon. It’s the new world. Great quantities of free land occupied only by savages.”

He had not been sure where Oregon was, but when another group of men and women appeared in Lancaster buying wagons and Melchior Fordney rifles, he had asked them when they stopped at the Zendt stall for smoked meats, “Where’s Oregon?”

“Two hundred and fifty days from here, heading westward all the time. But it’s a great country. Malachi here went there by boat. He’s our captain.”

Oregon of the savages! Oregon of the free land, the new life!

On Tuesday at eleven, when the market was jammed, both with normal customers and with sensation-seekers who had heard that Levi Zendt was going to apologize in public, stern Mahlon led his youngest brother through the mob and up to the counter of Peter Stoltzfus. In a loud voice he cried, “Brother Stoltzfus, here is a man who wishes to speak with you.”

Peter Stoltzfus, dressed in white apron, leaned over the edge of his stall and glowered at the man who had tried to rape his daughter. “Becky, come here!” he called, and from between the curtains masking the back of the stall Rebecca Stoltzfus appeared, so fresh and beautiful in her carefully pressed clothes and so neat in her little white cap with the dangling strings that the onlookers gasped to think that a human beast had tried to defile her. Several women, imagining that they had once looked like that, started to weep.

There was an awkward silence, whereupon Mahlon jabbed Levi in the back and the latter began to speak, in a whisper so low that no one could hear. “Speak up!” several men shouted.

“I am sorry, Baker Stoltzfus …” Levi simply could not go beyond that, and Mahlon grew tense with rage at this new humiliation.

The impasse was ended by Peter Stoltzfus, who leaned down from his stall and punched Levi so solidly in the nose that the young butcher staggered backward, tripped over Mahlon’s foot and fell flat on his bottom. The crowd cheered and a man’s deep voice shouted, “Give him another, Peter.”

That was the end of the apology. Mahlon, filled with disgust, abandoned his brother, and the other Zendts returned to their own stall, nodding approvingly across the aisle to Peter Stoltzfus and his daughter. Rebecca stayed at the counter, receiving the condolences of numerous women, and after a protracted moment on the floor, where he was too humiliated even to rise, Levi Zendt pulled himself together, rubbed his nose where Stoltzfus had thwacked him, and left the market.

That night, at five, he loaded the sleigh with the leftovers and drove out to the orphan asylum, where the mistress called him a human beast, directing him to unload the stuff and begone. But as he was working alone, Elly Zahm, the factotum, came to help him. She was a scrawny child, sixteen years old, an orphan whom it had been impossible to place in any private home. She knew how to work and was industrious; normally she should have been picked up as a maid-of-all-duties, but she was so unappealing in appearance, with straggly hair and thin face, that no one wanted her.

She lifted a basket that would have taxed a man, and Levi said, “Leave that one for me,” but she already had it indoors.

“I heard what they said about you and the Stoltzfus girl,” she said with precise accent. “I can’t believe it.”

Even here! His face grew a deep red and his hands trembled. Was it to be like this the rest of his life: “What about you and the Stoltzfus girl?” Leaving the baskets behind, he leaped into the sleigh and whipped the horses through the asylum gate.

Wednesday and Thursday were days of deepest anxiety. The Mennonites of Lancaster County were a lusty lot; they were by no means prudish, and their language could be most robust, with words that would have shocked ordinary Baptists or Presbyterians. They particularly liked to use barnyard terms, which made a Lancaster County saloon a rather lively spot, with constant reference to bowel movements, urination and sexual intercourse. It was not through prudishness that the Mennonites turned their back on Levi Zendt; it was because tradition required that sexuality be expressed in words rather than actions. For one Zendt boy to break out of the restraints that had bound the other four was intolerable and a menace to the whole community.

Therefore, without a formal vote, the Mennonites decided to shun him. From that moment he became an outcast. He could not attend church, nor speak with anyone who did. He could not buy or sell, or give or take. He could converse with no man, and the idea of striking up a friendship with any woman was beyond imagination.

“They’re shunnin’ Levi Zendt!”

“About time. That animal.”

On Friday, when he walked from the farm to Lancaster, no passer-by would offer him a ride. The black sleighs skidded past as if he were a pariah. And when he reached the market, none of the merchants would talk with him. At the end of the day he loaded the gifts and drove out to the edge of town, where the mistress of the orphanage refused to speak to him, but Elly Zahm appeared as usual to help him unload.

“I hear they’re shunning you,” she said. He was too anguished to reply, and she said a most peculiar thing: “They’ve been shunning me all my life.”

The words made him look up. For the first time he saw this skinny, unlovely child whose hands were so red from overwork and whose eyes seemed so very old. He could say nothing, and left as abruptly as he had the previous time.

But as he drove through the gathering dusk and approached Lampeter, he pulled up at Hell Street and went boldly into the White Swan. “Is Amos Boemer here!”

The bartender nodded toward a corner, where the tall wagoner sat in a stupor. Levi went over to him, shook him and asked, “Amos, you want to sell that Conestoga?”

Amos tried to clear his eyes, saw only a dim shape, and mumbled, “I wanta give the bullshit thing away.”

“How much?”

Now the wagoner’s head cleared. “That wagon was made by Samuel Mummert. Paradise. 1818. It cost two hundred dollars. It’s a great wagon.” He tried to stand but could not. “A man would be crazy to sell that wagon.”

“How much?” Levi asked.

“Twenty dollars and you can kick that bullshit thing all the way to Philadelphia. It ain’t worth a nickel.” He fell forward, but as Levi continued to pester him he rose, stared at the intruder and demanded, “Ain’t you the Zendt boy? Goin’ around rippin’ the clothes off decent girls. Get the hell out of here.” He pushed Levi toward the door, cursing him savagely long after he had departed.

Two weeks later, when the snow was gone, Levi walked down to Hell Street, ignoring the stares that marked his passage. He went to the White Swan and again rousted Amos Boemer from his corner. “I want to buy your Conestoga,” he said.

“I’m not sure I want to sell. That’s a very good wagon.”

“I know. I want to buy it.”

“Twenty dollars and it’s your’n.”

“Here’s the twenty dollars,” Levi replied, offering him money saved from his wages.

“It ain’t got no bells.”

“I don’t need bells.”

In that way Levi Zendt became owner of a Conestoga a quarter of a century old. It had been built with great care by one of the best workmen in the area, and had seen much good service on the Philadelphia freight route. It had suffered no broken boards; its toolbox and wagon jacks were usable, and its lazyboard worked. The twenty-four bells were gone, it was true, but where Levi was thinking of going, bells were not desirable.

To haul the wagon he would need six horses, and he had but two, a pair of sturdy grays. During the following week he bought two additional grays from a farmer in Hollinger, but told him to keep them until called for. The farmer said that he would need pay for their boarding, and being in an amiable mood, said, “You hear of the city feller who wanted to board his horse and he asked his friends what he ought to pay and they said, ‘The price ranges from one dollar a month to fifty cents to two bits, but whatever you pay, you’re entitled to the manure.’ So this city feller goes to the first farmer, and the farmer says, ‘One dollar,’ and the city feller says, ‘But I get the manure?’ The farmer nods, and at the next place it’s fifty cents, and the city feller says, ‘But I get the manure?’ and the farmer nods. At the third farm two bits and the same story, so the city feller says, ‘Maybe I can find a place that’s real cheap,’ and he goes to a broken-down farm and the man says, ‘Ten cents a month,’ and the city feller says, ‘But I get the manure?’ and the farmer says, ‘Son, at ten cents a month they ain’t gonna be any manure.’ ” The farmer laughed heartily. Levi forced a smile and walked back to his farm.

He now had four grays, and he knew where he would get the other two. He would “borrow” them from his brother Mahlon.

It would be impossible, of course, to go west or anywhere else without one more essential item. He would need a gun. For a Lancaster man to move even across his own farm without a gun was unthinkable. The so-called Kentucky rifle, which had played so powerful a role in the War of Independence and had practically decided the War of 1812, was in truth a Lancaster rifle, invented and perfected in the smithies and shops of this town. Now, in days of peace, the Lancaster gunsmiths made the best hunting rifles in America, and their finest products rivaled those of Vienna.

Levi had never owned a gun. He was a good shot but so far had always used his brothers’ guns, and now he faced a dilemma. He had the money, but how could he, under penalty of shunning, march into the shop of Andrew Gumpf or one of the Dreppard brothers and try to do business with them, they being such good churchmen? He devised various stratagems but none seemed practical. He really was an outcast.

Then he thought of Melchior Fordney, who made a very good gun but who was somewhat out of favor with the decent people of Lancaster because he had up to now refused to marry his housekeeper, a Mrs. Tripple, whom they suspected of living with him carnally, without sanctification by the church. Fordney was a strong-minded individual, and if anyone in Lancaster would sell Levi a gun, it would be he.

So on the first of February, Levi quietly slipped out to where Fordney had his gunsmith’s shop. An automatic bell jangled as he opened the door and a pleasant woman in black dress and white apron but without white cap appeared: “Mr. Fordney? He’s workin’ in back. I’m Mrs. Tripple.”

“Came to see about a gun,” Levi said, almost aggressively.

Mrs. Tripple was accustomed to country lads who took the offensive in such matters, and she said easily, “You wait chust there. I’ll call the mister.”

In a moment Fordney appeared, a brawny man with great square shoulders and features to match. “Now what is it?”

“I want a good rifle.”

“How much you prepared to pay?”

“I could go as high as twelve dollars … but only for a good one.”

“For twelve you get a good one.” Brushing aside two rifles that lay on his workbench, he said, “Those two, five dollars each, but you wouldn’t like ’em.”

Levi hefted one, found it balanced too heavily toward the stock, and said, “That one I wouldn’t like.”

“You noticed?” Fordney laughed. “A little wood heavy. Now, I have a fine rifle over here, but it’s eighteen.”

“Too much,” Levi said. In the rack he noticed an older gun with a most handsome curly-maple stock, well worked with brass fittings. Fifty-five inches long and with an octagonal bluish barrel and a ramrod of well-used hickory, it was a fine weapon, almost the epitome of a Lancaster rifle. Unfortunately, it still carried the old flintlock mechanism.

“Can I see that one?”

“That’s a very special gun,” Fordney said.

“Would it cost too much?”

“No. I could let you have that’n for twelve dollars. But it’s flintlock, as you can see. Made it for a man nineteen years ago.”

Fordney pulled the rifle down and showed Levi the date etched into the top of the barrel: “M. Fordney. 1825.” Levi took the gun, fitted it to his shoulder, and said, “I never felt a better.”

Fordney watched him handle the piece and liked the way he used it. “Aren’t you the young Zendt fellow?” Levi blushed. “The one they been shunnin’?” He called Mrs. Tripple and told her, “This here’s young Zendt. The colt that acted up with the Stoltzfus girl.”

“She needed some acting up with,” Mrs. Tripple said, returning to her kitchen.

“So the rifle’s yours for twelve dollars.”

“I don’t know how to work a flintlock.”

“Hold your horses. I’ll change the flintlock to percussion.”

“You will!” Levi’s voice proved the delight he felt at the prospect of getting such a gun. He put it to his shoulder again and asked, “Is this gun as good as it feels?”

“One of the best I ever made. Man used it six years, then traded it back to me for a percussion. Stupid ass. I told him I could switch it to percussion, but he said, ‘I don’t never want nothin’ that’s been altered.’ So now you get a bargain.”

He told Levi to come back later, but the young man replied, “I’m not doin’ anything,” and Fordney, realizing that he had nowhere to go, said, “You can watch,” and he rummaged among his boxes to find the bits of gear that would be required to switch the old flintlock over to a new percussion-cap mechanism. Placing each item on the bench before him, he took the beautiful gun he had made so long ago and began disassembling it.

He unscrewed the frizzen spring and removed the frizzen altogether. He dispensed with the flash pan, too, and the hammer that had held the flint. Then with a hard black gum mixed with metal filings, he packed the screw holes and sanded them over. With a file he enlarged, ever so gently, the touch hole and rammed in a graver which would thread it. Into this hole he screwed the drum, adjusting the nipple so that the hammer would strike properly.

Testing the new mechanism many times to see that all parts functioned, he then grabbed a handful of percussion caps—little forms of powder that looked like a man’s top hat—and motioned Levi to follow him outdoors. They went to a field, where Fordney swabbed the bluish barrel, poured in the right amount of powder, pushed down the greased patch to form a bind, inserted the ball and then placed the percussion cap on the nipple. Handing the gun to Levi, he said, “Hit the tree over there,” and Levi placed the stock against his shoulder, felt the sleek brass inlays and sighted along the barrel. Squeezing the trigger with gentle, even pressure, he heard the hammer trip, caught a glimpse of it descending on the percussion cap, saw the momentary flash and felt the powder inside the barrel explode, sending the bullet in a revolving motion straight and true to the limb he had aimed at.

Fordney said, “The Fenstermacher boy, that’s the preacher’s son, he told me he could load and fire a gun like that three times in two minutes. I didn’t believe him, but he could.”

Levi fired two more shots and then Fordney tried his hand. It was a good gun, subtly balanced, beautifully crosshatched at the wrist. In some respects it was better now than when it had first been sold, for the curly maple was seasoned and the barrel had nested with no chance of gaps.

Fordney handed the gun formally to Levi and said, “None better. Oh, I have some for twenty or twenty-five, but only because the brassware comes from Germany. This one, all Lancaster.”

As they walked back to the shop Fordney said, “I’d ask you if you wanted to work with me, seein’ as how you like guns, but I suppose you’ll be headin’ west.” Levi felt it prudent to say nothing, and Fordney added, “I should have gone west … years ago.”

Levi smuggled his rifle home and hid it behind the sausage machine. He now had a good Conestoga, four excellent gray horses and two of Mahlon’s he intended to borrow. He had a vague plan of hooking up with the next caravan of people moving west. He would tolerate Lancaster and Lampeter no more. Even if they relaxed the shunning, which they probably would in the spring, he would not live down his disgrace.

He went about his work as industriously as ever, grinding the pork, mixing it with herbs and cramming it into the holder on the sausage machine. When it was filled to the top, he attached one end of a cleaned hog’s gut to the spout on the machine, then by cranking a large wheel which operated a screw, he applied pressure on the ground meat and slowly it forced its way into the farthest knotted end of the intestine. When the skin was filled to bursting, he took the open end off the machine and tied it in a tight knot, giving him eight to ten feet of the best sausage. Later, when it had set, the length would be cut to selling size.

He made his scrapple with added care, as if he were just learning the trade, cooking the pig scraps and the cornmeal for hours, spicing them just right and pouring the hot liquid into small deep pans, where a good inch of yellow pork fat would gather on top, airproofing the scrapple so that it could be kept for three months.

He was a good butcher, and he assumed that when he got to Oregon he would continue making scrapple and sausage and souse. There won’t be many out there can make any better, he thought.

Each Tuesday and Friday he walked the long distance into Lancaster to clean up the market and drive the scraps out to the orphanage, and on the fourth week after shunning started, he asked Elly, “Why did they shun you?”

“I have no parents. They called me a bastard.”

“That’s not your fault.”

“They let on as if it was.”

“How’d you get here?”

“They found me on the church step.”

He said no more that day, but when the other Zendts were in church, he walked down to the grove of trees and sat for a long time in silence. He straddled the trunk of a fallen oak and looked carefully at each part of the handsome farm his family had accumulated, one building at a time, one field patiently after another. There was no better farm in Lancaster County and he knew it, but it had grown sour—it had grown so terribly sour.

He covered his square, beard-trimmed face in his hands. He was not a man to allow tears, but he did sigh deeply and mutter, “I will stand no more. On Tuesday morning I will leave this place.”

At the big Sunday dinner he ate as if he had been starving for a week, taking big helpings of everything and ending with two kinds of pie, shoo-fly, whose sticky bottom he loved, and cherry, the best of all. He was congenial to everyone, and on Monday he volunteered to help his mother make cup cheese, a fact which startled her; when he got to Oregon he wanted to know how it was made.

He noted carefully as she took a couple of gallons of milk and cream that she had allowed to sour and put it on the stove to heat. “Don’t boil it … ever,” she warned. “Just hot enough to ouch your finger.”

He was disappointed when all she did was strain off excess water and place the curds in a bag. “What happens next?” he asked.

“Oh, tomorrow you can help me again. I crumble the curds and rub in this much soda, and we’ll put it in a crock. It’ll sour and smell and become runny. Then it’s ripe, so you set the crock in hot water till it’s warm again, and you stir in some salt and a little water with a squirt of vinegar in it.” She hefted the dripping bag onto a peg over the sink and said, “Tomorrow you can help me finish.”

Tomorrow he would not be here.

On Tuesday at three in the morning he helped load the Zendt wagons with the last batch of souse and scrapple and sausage he would make. He watched his four brothers drive off to town, and as soon as they were gone he went inside and kissed his mother goodbye. She guessed that he might be running away; his interest in cup cheese had been so unusual that she had tried to fathom why. She knew. She asked, “Where you goin’?” He replied with another kiss and went out to get his gun and his two horses. He also took the two belonging to Mahlon, plus whatever harness was needed.

He drove the four horses down to the White Swan and hitched them to the Conestoga. He left Hell Street in darkness, driving over to Hollinger to pick up the two horses boarding there. “That’s a fine team of six,” the farmer said approvingly. “Almost looks as if you’d matched ’em.” As Levi harnessed them to the Conestoga, completing his team, the farmer asked, “You’re the Zendt boy. Ain’t they shunnin’ you?”

“No more,” Levi said.

By back roads he drove past Lancaster and out to the orphanage. Pulling up outside the gate and hitching his lead horse to a tree, he started toward the house, but remembered his valuable gun lying unprotected in the wagon. Grabbing it, he went inside and bellowed, “Elly! Elly Zahm! Come down here!”

It was barely dawn but the work girl was up and busy at her chores. She appeared with her arms wet and her skirt tied behind her knees. Her scrawny face was red and her hair unkempt. As soon as she looked at Levi she knew that some powerful thing was afoot, and she was in no way perturbed when he said, “Get your things. We’re goin’ west.”

It took her three seconds—one, two, three—to know that her destiny required her to join this man, and his gun and his wagon, and his waiting horses. She had no conception of what was being asked of her, but she knew that there could be no viable alternative. She dashed inside the orphanage and grabbed the few things that belonged to her.

A girl shouted, “He’s taking Elly Zahm … with a gun.”

The mistress, not yet dressed, hurried to the front door in her gown, and with one glance, apprehended what was happening. “Elly!” she screamed. “Come back here.”

“I am never coming back,” the thin girl said stubbornly.

“That man’s a monster.”

“I’m going,” Elly cried, clutching her good dress in her arms as she hurried toward the Conestoga.

“Shall I fetch the police?” one of the girls shouted.

“No!” the mistress snapped. “He’d kill us all. Let her go. She’s nothing but a whore. Just like her mother before her.”

And that would have been the benediction with which Elly left the orphanage had not a tall, lively girl, blond and quite pretty, broken from the crowd of watchers, running to Elly and thrusting into her hand a small bag of carefully saved coins.

“Laura Lou Booker,” the mistress screamed, “come back here! You’re as bad as she is!”

Ignoring the command, the tall girl clasped Elly, kissing her fervently on the cheek. “You’re escaping for all of us,” she whispered, and when Elly tried to return the precious money, Laura Lou kissed her again, whispering, “Remember what we said. A wife must have a little money of her own.”

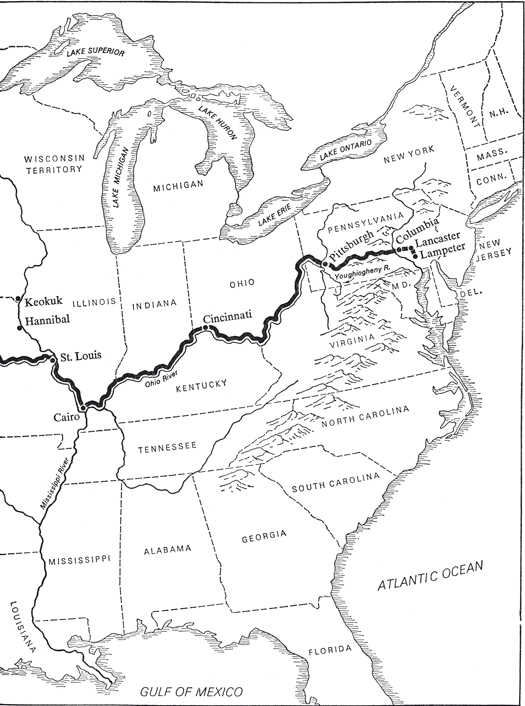

Clutching the few dollars, Elly Zahm, sixteen years old, walked resolutely through the gates of the orphanage and climbed into the Conestoga. Levi Zendt, his Melchior Fordney rifle in his left hand, called to his six horses and headed out of Lancaster for the last time.

It was only twelve miles to Columbia, where the famous bridge waited to lift them across the mighty Susquehanna, but because the six grays were new to the wagon and to each other, the going was slow. They did not reach the river till nightfall, and when they did the tollgate was closed. This required that they sleep on the eastern bank, and as the stars appeared, Elly faced the first crisis of her long trip west.

“We cannot share the wagon till we’ve been married,” she said. “I’ll sleep under that tree.” Taking a blanket, she prepared to do so.

This Levi would not permit, for he realized that as a gentleman he must allow her to have the wagon, but she had a practical mind and said, “You must guard the wagon. Our things are there.” And she slept beside the Susquehanna.

In the morning Levi asked, “Would you like it if we found a preacher on the other side?”

“Very much,” she said. “I want no bastards.”

Levi hitched up the horses and got the Conestoga into line for the crossing. The man in the wagon ahead turned out to be a German on his way to Illinois, and as they waited he came back to talk with the runaways. “In our schoolbooks in Germany we had pictures of this bridge,” he said, pointing to the engineering marvel. “Longest bridge of its kind in the world.”

Levi was impressed that so great a thing could have existed so close at hand without his having known of it. He told the man, “In Germany you have pictures of Lancaster, and in Lancaster we have pictures of Germany,” but Elly pointed out, “This isn’t Lancaster. It’s Columbia.”

The fee to cross, for a wagon with six horses, was one dollar, which Elly thought excessive, but the German called back, “For two dollars such a bridge would be cheap.” And they entered upon the very long covered bridge, with its two separated tracks plus a third for persons walking their horses.

When the heavy wagon reached the western end of the bridge Elly said, “The minister in that church ought to be up by now,” so at half past seven in the morning they rousted out Reverend Aspinwall, a Baptist minister, who said, “I couldn’t possibly marry you without knowing who you are. You’d have to show me a proper clearance from your church and then get a legal license at the courthouse in York.”

“How far’s York?” Levi asked, and Reverend Aspinwall said, “Twelve miles,” and Levi said, “That’d take all day.” Elly began to cry, and when Aspinwall asked why, she told him, “Always they called me a bastard. I don’t know whether that’s right, because I had no parents. But my children won’t have that name.”

“They mustn’t,” Aspinwall said. “Can’t you ride into York for your license?”

“We cannot,” Levi said sternly.

“No, I suppose not,” the minister said. He blew his nose and considered the matter. “Tell you what,” he said. “There is such a thing as marriage-in-common. You announce to the world that you’re going to live as man and wife, and if you have two witnesses …”

“Where would we get witnesses?” Elly asked.

Reverend Aspinwall, looking at her unprepossessing face, doubted that she would ever again find a man who might want to marry her. If it were to be done, it had better be done now. Coughing, he said in a low voice, “Mrs. Aspinwall and I would be your witnesses.”

He called his wife and said, “Mabel, these young people don’t begin to have their papers in order. But they must be married now.”

Mrs. Aspinwall stared at Elly’s middle and could see no visible evidence of need. How thin the girl is, she said to herself.

“So I wondered if you and I could serve as witnesses to their intention?”

“Certainly.” She took Elly’s hand and said, “A girl needs someone to stand with her, doesn’t she?”

Taking a position in front of his desk and with no Bible, Reverend Aspinwall said, “In the eyes of man and in the presence of God these two young people …” He stopped, looked at Levi and said, “I don’t believe I have your name.”

“Levi Zendt.”

Reverend Aspinwall gasped. “Aren’t you the young man who tried to …” He could not force himself to say the word.

“It did not happen that way,” Elly interrupted.

“I heard all about it. The Stoltzfus girl. I know Peter Stoltzfus.”

“It did not happen,” Elly said stubbornly.

“How could you know whether it happened or not?” Reverend Aspinwall asked sternly. “Has he raped you, too. Is that why you …”

“I know it didn’t happen because I followed the sleigh,” Elly cried.

“Why would you follow a sleigh? At night?”

“Because I love him,” she said. “Because I’ve always loved him. Because he’s the only man in this world who has ever been nice to me.” She broke into tears.

Mrs. Aspinwall tried to take the sobbing girl to her bosom, but Elly tore herself away and confronted the minister. “I saw the whole thing. She flirted with him something awful. She teased him about never going with girls. She was to blame. She did it all.”

There was a moment of embarrassed silence, during which the minister blew his nose and his wife tried to comfort the girl. After coughing several times, Reverend Aspinwall resumed: “In the presence of God these two young people, Levi Zendt and Elly—your name, child?—Elly Zahm announce their intention to be husband and wife. In the presence of two witnesses, that is.” He coughed again, then dropped into his ministerial voice and prayed: “God, have tenderness toward these children. Cherish them. Help them, for they are going into territories they do not know. Keep them in Your love.”

With that he raised his hands to indicate that the service, such as it was, had ended, but Elly asked, “Do we get a paper?”

“Not from me,” Reverend Aspinwall said. “This isn’t a formal marriage, you know. And he’s outcast from his own church. I cannot lend it the appearance …” He hesitated in embarrassment.

“I can,” Mrs. Aspinwall said.

She went to her husband’s desk and took a sheet of paper on which his name and the address of his church had been imprinted. On it she wrote in bold letters:

On this day Levi Zendt and Elly Zahm appeared before my husband and me and in the sight of God Almighty announced their intention of living together as man and wife, in the state of Holy Matrimony.

Witness

Mabel Aspinwall

February 14, 1843

She handed the paper to her husband, indicating where he was to sign, and with visible reluctance he did so.

“How much?” Elly asked.

“No, no!” Aspinwall protested.

“Here,” she said, handing him one of Laura Lou’s dollars. “It makes it more proper.” She folded the paper neatly, tucked it in her dress, and the trip west was begun.

The journey to York was spent in getting to know the horses. The two lead ones were Levi’s own, and they responded well to his directions. The two nearest the wagon were Mahlon’s, and Levi had a pretty good understanding of what they might do, but the two bought horses in the middle posed some problems, for they did not feel comfortable working behind the lead pair and showed their uneasiness at every turn in the road by pulling against the traces.

Patiently Levi corrected their fractiousness, and at last he had the satisfaction of feeling them working together. “This is gonna be a great team,” he told Elly, who watched with pride as the six handsome grays moved stolidly forward, pulling the heavy wagon with no apparent strain.

About halfway to York, Levi got his first jolt. A traveler coming eastward stopped to admire the horses and said with visible conviction, “Neighbor, if you’re plannin’ to go over them mountains ahead, I’d shed myself of that Conestoga and get me a smaller rig.” When Levi argued against this, the traveler said, “Hell, man, you ain’t usin’ half that wagon. You don’t need one that big and you’re just pullin’ dead weight. Ain’t fair to the horses.”

This charge cut Levi, for if there was one thing he tried to be, it was considerate of his horses. He discussed the matter with Elly, and to his surprise she sided with the stranger. “It is half empty,” she said.

“Day’ll come we’ll need it,” Levi said stubbornly.

“You’re gonna kill your horses,” the stranger repeated, cracking his whip as he moved eastward to the Columbia bridge. When he was gone Levi mumbled, “You see his horses, Elly? They need rest and a good washin’-down, but he has time to lecture me.”