IN SPRING OF THE YEAR 1851 AN EXCITING RUMOR SPREAD across the western plains. Comparing partial information, men convinced themselves that portentous things were afoot.

The rumor started in Washington and moved swiftly out to St. Louis, where it was further augmented. By the time it reached St. Joseph it was raging like a prairie fire, and the farther westward it went, the more alluring it became.

“Yessir,” a mountain man affirmed at the Pawnee village, “the U.S. gov’mint is finally gonna grasp the bull by the horns.”

“And do what?” a suspicious trapper from Minnesota asked.

“We’re gonna have a great meeting … all the tribes on the plains … and we’re gonna settle once and for all who owns what.”

A chief of the Pawnee, hearing this heady talk, asked, “Great White Father, he come? Make peace?”

“He wouldn’t come hisself,” the mountain man explained, “but he would sure send his commissioners and Indian agents. It’s gonna be peace.”

The news sped along the Platte as fast as men could ride, and nowhere did it create more commotion than at Fort Laramie, where a small detachment of one hundred and sixty soldiers under tall, prim Captain William Ketchum, accepted responsibility for the safety of an empire. A trader bringing in six wagons of goods for Mr. Tutt, who ran the sutler’s store, reported, “I heard for sure it’s gonna happen. Mebbe two hundred, three hundred Indians brought to this fort—right here—for one great powwow.”

“We couldn’t handle three hundred Indians,” Ketchum protested. “Look at us!” He pointed to one of America’s most curious military establishments: within a curving sweep made by the Laramie River stood an old adobe fort long used by fur traders and emigrants. Since it was obviously inadequate and probably indefensible, new buildings were being erected along the sides of an impressive parade ground, but at this moment only two were in operation—the sutler’s store at the far end and the residential building, a two-storied plantation affair that looked as though it belonged in Virginia. Ultimately, plans called for a palisade to enclose the area, with two tall towers at the diagonal, but it certainly did not exist now, a fact of which Captain Ketchum was painfully aware. Pointing once more to the empty, unprotected space, he complained, “We could not defend ourselves. It would be a massacre.”

“Well,” the trader said enthusiastically, “here’s where they meet. Three hundred of ’em. Gonna settle all territorial claims. Peace for all time is what Washington wants.” And with this he led his wagons to the sutler’s, where the long-needed goods were unloaded.

Captain Ketchum was worried. Sending his orderly to fetch Joe Strunk, long-time mountain man serving as guide and interpreter, the captain said with some bitterness, “Word from St. Louis is that three hundred Indians will be convening here … peace treaty of some kind.” Obviously he did not relish the idea.

“They’d overrun us,” Strunk protested. When he had first heard that the United States was building a fort at Laramie he was pleased. It would help police the various trails that were beginning to crisscross the west. But if the government wanted a real fort in this territory, with no support for six hundred miles, it ought to be a protected fort, not a large open space.

“If the redskins got started, it could be a massacre,” he said dolefully.

“My very words!” Ketchum said.

“They been talkin’ peace for the last ten years,” Strunk observed, “and we got more war across the prairies now than ever before.”

This was not correct. In the middle years of the nineteenth century more than 350,000 emigrants moved along the Platte River from the Missouri to the Pacific, and the bulk passed through Indian lands without encountering difficulty. Something less than one-tenth of one percent of the travelers were slain by Indians—fewer than three hundred—whereas many times that number were killed by their own rifles, or the rifles of friends fired accidentally, or the gunplay of criminals who had joined the procession.

There have been few mass migrations in history so peaceful, and no previous instance in which people of one race passed through lands held by another with such trivial inconvenience. For this good record the Indian was mostly responsible, for it was his willingness to abide the white man that allowed the two groups to coexist in such harmony.

“What we got,” Strunk explained, “is petty warfare. Crow against Sioux. Shoshone against Cheyenne.”

“And we also have Broken Thumb,” Ketchum said with some distaste as he pointed to a tall, rangy Cheyenne in his mid-thirties who lounged insolently outside the gates of the old fort. “Broken Thumb!” he called. “Come over here.”

Slowly the chief detached himself from the Indians with whom he had been talking and very slowly walked the considerable distance from the adobe fort to the new white building. He moved as if he were coming to a fight, a scowl marking his broad, dark face, a gun cradled in his arms. Among the tribes he was a disrupting influence, for he was burdened with a bitter knowledge: he understood what was happening to his people in an age of change.

When he had approached near enough for Ketchum and Strunk to see the contorted right hand from which he took his name, he uttered one word in Cheyenne, “What?”

“Great White Father says he wants peace,” Strunk said in the same language. “You want peace?”

Broken Thumb stared at the mountain man, then at the captain, and waved his right hand. It had been crushed when he fell under the wheels of an emigrant wagon while stealing food. “What is it you call peace?” he asked. “You give us firewater to drink, and we become a nation of foolish men.” Here he danced a few steps, imitating a drunken Indian. “And while we are drunk you take our women and drive away our buffalo. Once they were more plentiful than our ponies … here where the two rivers meet … now where have they gone?”

“Two years ago you brought in thirteen thousand robes,” Strunk reminded him. “Mr. Tutt gave you many goods—scarlet cloth, beads, looking glasses, that gun you have.” He snatched it to point out the mark on the stock.

Broken Thumb grabbed the gun back and said harshly, “And this year, what robes? Where have the buffalo hidden? Like us, they cannot stand the white man’s ways and have left their old grounds.”

When this was translated, Ketchum assured him, “They’ll come back. I’ve seen a hundred thousand buffalo along this river, and we’ll see them again.”

“If we could have peace,” Strunk asked, “would you want it?”

For a moment the Cheyenne’s broad face relaxed, and he looked at his two interrogators with the eyes of a man willing to negotiate difficult matters. “We can have peace,” he said quietly, “if the commissioners come here like men and settle the four big problems …” The amiability vanished and he growled, “But the commissioners never come. Only soldiers. Only fighting.”

“Ask him … suppose the commissioners really did come? What four problems?”

Broken Thumb considered for a moment and concluded that he was being subjected to a trick. For years the Indians had sought a meeting with the Great White Father, one where they could smoke the calumet and talk about the prairies and the buffalo and the roads that crossed their lands. They no longer had hope that such a meeting could be arranged. And now Broken Thumb turned abruptly away. “No more talk,” he said in English. With that he strode from the fort, mounted his pony and splashed his way across the Laramie River toward the area where his tribe was encamped.

Then, in early summer, real news reverberated from the Missouri to the Rockies: “Yessir, a huge assembly of chiefs at Fort Laramie. End of August. All questions to be settled.”

Trappers employed by Pierre Chouteau and Company in St. Louis, lean hard-bitten men who dressed like Indians and fought them when necessary, penetrated to the Pawnee, the Cheyenne, the Arapaho, the Comanche and the Kiowa with the reassuring news: “Great White Father sends greetings. You come to powwow, he bring many presents.”

To the northern tribes that clustered along the Missouri—the Mandan, the Hidatsa, the Arikara—went a remarkable emissary, one of the bravest men to operate throughout the region, Pierre Jean De Smet, a Jesuit priest from Belgium, whose word was accepted by all the tribes. “It will be a famous gathering,” he told them in the many languages he knew. “The Great Father is sending rich presents, and if you come to Fort Laramie, all things that worry you will be settled.” It was largely due to his persuasiveness that the northern tribes began to weigh the unlikely possibility that real peace might be at hand.

To the fort at Laramie came the most reassuring messenger of all, a major in the United States Army serving as Indian agent with specific powers to set the vast operation in motion. He arrived one July morning, accompanied by seven cavalrymen and a charming woman in her thirties, all of whom had ridden hard from St. Joseph.

“Great news!” the major called before dismounting at the entrance to the fort. “A treaty to be signed!” When he got off his horse the soldiers at the fort saw that he limped noticeably in his left leg and they judged that this was not the result of some temporary soreness but a permanent thing.

Captain Ketchum came out to greet the arrivals, but before amenities could be concluded, the major cried, “It’s done, Captain! The treaty’s to be signed here.”

“What’s this about a treaty?” Ketchum asked.

“Supreme Court says the Indian tribes are nations. With nations you have treaties.”

Ketchum frowned and asked, “How many extra soldiers will they send me?”

“Cheer up! There’s talk of a thousand new men. Twenty-seven wagons of gifts for the tribes. Two commissioners and God knows how many interpreters.”

“How many Indians are we to expect?”

“Depends on what luck Father De Smet has. Could go as high as six hundred.”

“We’ll need more than a thousand extra soldiers,” Ketchum began. Then, realizing how rude he was being, he said, “I haven’t welcomed this charming lady to our fort.”

“My wife, Lisette Mercy.”

Before the captain could reply, Lisette had dismounted and grasped him by the hand. “Think nothing of ignoring me.” She laughed. “Maxwell’s always that way.” And she moved graciously onto the porch of the new building. “Shall we be staying here?” she asked.

“Yes,” the captain stammered. “We’ll …”

“Good!” And with that she returned to her horse and started unpacking her gear.

“Give the lady a hand,” Ketchum called, but before any of his men could reach her, she had her small bags unfastened and on the ground.

“I shall love it here,” she said enthusiastically. “I can see the Indians, now, hundreds of them … on all those hills.”

This was a most unfortunate image, and Captain Ketchum winced. He did not relish the touchy prospect of having six hundred Indian braves on those hills when he might have only two companies of dragoons and one of infantry to defend the place, protect the incoming caravans and serve the commissioners. As soon as he and Mercy sat in his quarters he said, “I need assurances, Mercy. Will there be at least a thousand new men?”

“Unquestionably!” Mercy replied.

“And there will be twenty-seven wagonloads of gifts? We have practically none left, and Indians will not accept any agreement unless it’s solemnized with gifts.”

“I saw the wagons at Kansas City. Knives, guns, food, everything.” He broke into laughter. “And an amazing special gift for the chiefs. Every time I think Washington is filled with imbeciles, someone there comes up with an idea that dazzles me.”

“What is it?” Ketchum asked suspiciously.

“You’ll be astounded,” Mercy said. He then turned to more serious matters. “We’ve sent word to all the tribes. Canada to Texas. We want to build one treaty that will encompass everything.”

“Will they all send representatives?” Ketchum asked.

“That’s what I’m to find out. Where are the Arapaho and Cheyenne camping?”

Captain Ketchum sent for Strunk and asked, “Where are the tribes right now?”

“Last we heard, Oglala Sioux west of the fork. Shoshone far to the west of Laramie Peak. Cheyenne down at Horse Creek, the Arapaho at Scott’s Bluffs …” He was prepared to list six or seven more locations, but Mercy had heard enough.

“Could Strunk and I ride down to the Cheyenne … right now?”

“Of course,” Ketchum agreed, and a party of nine was organized.

“You can show Lisette where to put our things,” Mercy said as he transferred his saddle to a fresh horse.

“Where’d you get the limp?” Ketchum asked professionally.

“Chapultepec,” Mercy said without emotion. “With General Scott.”

“Was it bad … down there?”

“Oh, you’d go for days with no action—never see a Mexican—then they’d dig in at some spot of their own choosing, and it would be lively hell.”

“They fight well?”

“Everyone seems to fight well on his own terrain.”

“Doctors can’t do anything for the leg?”

“The hip. No, I’ll be a major the rest of my life. Crippled … and damned fortunate to be alive.” With this he leaped into his saddle as easily as if his hip were sound, and set out for Horse Creek.

The party rode east along the Platte for thirty miles to where Horse Creek began to join the larger stream, and some miles to the south they found the tall, neat tipis of the Cheyenne, arranged, as always, in circles. It was a beautiful, orderly community, with the side flaps of the tipis raised to facilitate the circulation of summer air, and it bespoke the solidity of this tribe.

“Where’s Broken Thumb?” Strunk asked in Cheyenne.

“That tipi,” a boy replied, and the men rode there.

Only Strunk and Mercy dismounted; the seven soldiers remained on guard, their rifles at the ready across their saddles.

When Major Mercy stooped to enter the tipi he could not immediately adjust his eyes to the darkness, but after a few moments he saw confronting him five Indians informally dressed, and out of the shadows loomed the faces of the men who would determine Indian activity in this region for the next fourteen years.

In the middle sat a man Mercy already knew—a man with a dark scar down his right cheek and the tip of his left little finger missing. It was his own brother-in-law, Jake Pasquinel, now forty-two years old and tense with the disappointment which comes at that age when a man realizes he has made too many wrong choices. Instead of staying with the Arapaho, among whom he might have achieved real leadership, he had drifted from tribe to tribe, learning many languages badly, fit only to serve as interpreter to men who were far less capable than he. Like all half-breeds he stood with one foot in the Indian world, one in the white man’s, and at ease in neither. He was trusted by no one, and suspicion was so constant that he had grown to doubt himself.

To his left, and in the seat of prominence, sat Chief Broken Thumb, twisting the ends of his braids with thumb and finger as if preparing to confront the white man with his string of grievances. Even sitting, he was a tall, impressive man, thirty-five years old and a proved warrior of many coups. Mercy, seeing him for the first time, said to himself, He’s like one of those volcanoes in Mexico. You see the ice in the eyes and can be sure the fire smolders below.

The man on Pasquinel’s right looked quite different—shorter, much less aggressive and apparently more introspective. He had a most handsome face, lean and hawklike, with prominent nose, exaggerated cheekbones and deep lines cutting vertically down both cheeks. His eyes were deeply recessed and very dark, and his whole appearance was given a somewhat grotesque touch by the fact that he wore a white man’s type of hat with moderate brim and very tall crown. It made him look unbalanced, as if both it and the head that wore it were too large for the body that supported them. He did not wear his hair in braids, like the others, but cut straggling-short about his shoulders. The conversation would be far advanced before this reticent chief, then in his forties, would speak, and when he did, it would not be in Cheyenne.

Now Broken Thumb prepared a calumet, keeping it on his knees while he mixed tobacco and kinnikinnick in prescribed amounts. When the pipe was filled and lit, he held it extended at arm’s length to the four compass points, then placed his right hand, palm up, at the extreme end of the bowl, drawing his fingers slowly back along the three feet of stem till they reached his throat. There, with a motion parallel to the earth, he brought his hand across his throat, signifying that what he was about to say was sacred and true. This was the oath of the Indian, the solemn promise of the pipe.

As the calumet passed to the other chiefs, Broken Thumb indicated that Mercy was free to speak, and the captain asked, “Have the messengers come from the Great White Father?”

“They came,” Broken Thumb replied cautiously, pinching his braids.

“And they told you that we can now have peace … forever?”

“They told us.”

“And will you send chiefs to our meeting?”

This was the difficult question, the one on which so much depended, and the three other chiefs sat silent, waiting for Broken Thumb to voice their thinking. Reaching for the calumet, he puffed slowly, then held it in his lap, cradled in both hands. Slowly, but with increasing fervor, he gave the Indian’s answer to the white man’s overture. It was a long speech and was interpreted by Strunk into English, and then by Pasquinel into an Indian language for the benefit of the silent chief to his right.

The White Father wants peace, so that he can send his traders safely through our lands. Of course he wants peace, so that thousands of wagons can cut trails. He wants peace so that his people can kill the buffalo and trap the beaver. But does he want peace strongly enough to deal with us honestly on the matters that divide us?

Here Major Mercy interrupted, intending to ask what the complaints were, but Broken Thumb silenced him imperiously, and spoke with heightened intensity, outlining their grievances. “Long time ago the white men who came across our land were good people. They wanted to build homes. They had their children with them. There was some fighting, but never much, and there was respect. But in the last two years, a different kind of men. Ketchum says ninety thousand came, and all they wanted was gold. Mean, hungry men with no women, no children. They shoot our people for no reason, the way they shoot antelope. They burn our villages for no reason, the way you burn the nests of hornets. They are ugly men, who have only war in their hearts, and we shall give them war.”

He referred this matter to the other chiefs and two of them supported him enthusiastically, with cries of “War! War!” Mercy noticed that the chief in the hat remained quietly brooding in the shadows.

“When the Great White Father determined on war with Mexico,” Broken Thumb continued, “he sent his soldiers across our land, and when they found no Mexicans along the southern river, they wanted to fight us and they killed many of our people. It was not we who started war, Mercy, it was you. We know that you were with the soldiers, because our braves saw you, and now you come here to talk with us of peace. We talk of war!”

Again the two Cheyenne chiefs echoed the defiance, and Mercy sat silent, staring at the floor in humbleness of spirit, because what Broken Thumb said was true. He had marched with his men from Independence along the Arkansas River and down into Texas and Mexico, and in their boredom the men had started shooting down Indians as if they had been turkeys, and villages were burned and squaws violated, and only the iron resistance of men like Mercy had prevented the affair from becoming a total massacre. He suspected that if the Indians knew he had been along, they also knew that it was he who was primarily responsible for halting the disgrace.

“And you must stop selling whiskey to our people,” Broken Thumb continued. “Mercy, what you are doing is contemptible.” In this sentence Broken Thumb used an Indian word Strunk did not know, and there was much discussion as to its translation. It was Mercy who suggested contemptible and when this was translated as without honor, the chiefs agreed. “Because at Fort Laramie the other day I stole a bottle of the real whiskey you drink among yourselves, and it was good to taste. These chiefs have tasted it,” and to Mercy’s astonishment he produced a half-filled bottle of whiskey imported from Scotland, which he asked Mercy and Strunk to taste, and it was the best. “But for us you sell this!” And he produced another bottle, filled with Taos Lightning, and he asked the white men to taste it, and when they refused, well aware of what it was, he thundered in English, “You drink! Goddamn, you drink!” Mercy took a small taste, and it would have been revolting even had he not known its components.

“Contemptible,” Broken Thumb said with deep bitterness. “For a small drink of this,” he said with scorn, “you charge two buffalo robes. With this you take away our squaws and make our children poor. Mercy, are you proud that when your soldiers with their rifles cannot defeat us in battle, you bring this among us to destroy us?”

He put away the bottles, being careful to cork the Scotch, and came to his final point. “Mercy, you must do something about the sickness, the one you call cholera. It has been so terrible among us. At the Mandan villages they were twelve hundred last year, and this year they are less than forty. White Antelope here has lost six members of his family. Tall Mountain has lost four. My wife and two children are dead. You have brought a terrible illness among us, Mercy, and we must have help.”

“It has killed us too,” Mercy said quietly, and he asked Strunk to inform the chiefs of the tragedies of recent years, of whole families of emigrants wiped out in an afternoon—a man would be driving his oxen, would feel nausea and would cry, “The fever!” and even his wife would shun him, and within four hours he would die, with the knowledge that four hours later his wife and children would be dead too. When Strunk finished his narration, Mercy said, “I have ridden this summer from the Missouri River to Fort Laramie and never was I out of sight of some grave. It has been as hard on us as on you.”

“Where did you bring it from, Mercy, you white people?”

“From out there,” he said, pointing to the west, “from across the great water.”

“Will it go on and on and on?”

“It will end,” he assured them. It had to end. It could not continue like this forever, or the world would be wiped away. A man required assurance that when he rose in the morning he would retire at night, barring some fearful accident against which there could be no reasonable defense. But to rise with the daily expectation that fever would strike, and that a few hours later he would be dead, was too much. “It will end,” he repeated, “for you and for us.”

“Will you send medicine?”

“At the forts there will be doctors.”

“Forts?” Jake Pasquinel interrupted.

“Yes, when we have the treaty, the Great Father will need five or six forts … here and there … you know …”

“I do know,” Broken Thumb said coldly. “You will have many forts, and they will require many soldiers, and the soldiers will need many women, and there will be many bottles of whiskey, and while we are drunk in our tipis you will kill the buffalo.” Here he passed into a kind of trance, and he spoke as if he were seeing a tormenting vision of the future: “And when the buffalo are gone, we shall starve, and when we are starving, you will take away our lands, the tipis will be in flames and the rifles will fire and we will be no more. The great lands we have wandered over we will see no more.”

“No more,” White Antelope repeated, and the words seemed to inflame Broken Thumb, and he became a man of iron.

“No!” he shouted. “We want no powwow … no peace … no surrender. It will be war, Mercy. I have prayed to the sacred medicine arrows and I know this to be true. I shall kill you and you shall kill me.”

He passed from reason into a frenzy, throwing himself about the tipi and waving his mangled hand in Mercy’s face, and with a wild gesture he grabbed the calumet and shattered it against a tipi pole. “It is war!” he shouted, his broad face dark and distorted, his braids shaking like snakes.

It was now that the chief in the hat began to speak. From the shadows he reached out a hand and pulled Broken Thumb down beside him, quietening him and saying in Arapaho, “No, it will not be war. If the Great Father wants to talk with us one more time, and if he sends a messenger like Mercy to assure us that this time the talk is serious, then we will meet with him. We will come to Fort Laramie and we will listen and try to fathom what he has in his heart. Like my friend Broken Thumb, I know that the treaty will be made and then broken. I have no hope that the white man can ever say something and mean it, because we never deal with the same white man. One makes the treaty, and he goes. Another comes, but he never heard of the treaty. With us it is different. When the calumet passes, every Arapaho now and to be born is bound.”

When this was interpreted, the chiefs assented, and the speaker continued: “Still we must try. So to you, Broken Thumb, I say, ‘The Cheyenne will go to Fort Laramie,’ and to you, Mercy, I say, ‘Tell the Great Father that Our People are willing to talk with him one more time, because we truly desire peace.’ ”

The speaker was Lost Eagle, chief of Our People, who were camped this summer farther to the east. He had come to discuss with the Cheyenne the message from St. Louis, and for two days he had been arguing, with Pasquinel as his interpreter, that the only hope for the Indian was a lasting treaty with the white man, one that would give the white man freedom to traverse Indian lands and the right to establish forts, and give the Indian a confirmation of his ownership of the land. He was a persuasive arguer, a man who had a view of the future quite different from Broken Thumb’s.

His words commanded attention, for he was known as a man dedicated to bringing his people safely through the troubled years that loomed ahead. He was the grandson of Lame Beaver, whose many coups filled the chronicles of Our People.

He now turned to Broken Thumb and said, “Friend, we stand—you and I—at the edge of a precipice like the ones our fathers used to stampede the buffalo over. But we must not allow ourselves to be stampeded. The white man’s bad medicine has struck us hard. The buffalo are no longer easy to locate. Strangers build forts and farms on our land, and we face many decisions. You are the bravest man I know, Broken Thumb, and often have I followed you to war against Comanche and Pawnee.”

Here he bowed gravely to the Cheyenne warrior, his tall-crowned hat dipping down to hide his face. “But with our few guns we cannot fight the white man with his cannon. If he loses a hundred men, he sends back east for replacements, but if you Cheyenne lose a hundred, where will you find their replacements? You have seen the thousands who have crossed our prairie, and more come at us every year.”

He paused to allow this reasoning to sink in, then asked for a new calumet, and with it took a special oath that what he was about to say was true: “If the white man wants to cross our land, he will do so, whether we give him permission or not. If his sons want some of our land to farm, they will take it, either with our permission or with a gun. I say, let us go with Mercy, who is our friend, and listen to what he has to say.”

As he spoke these conciliatory words, Mercy noticed that his interpreter, Jake Pasquinel, was becoming more and more impatient with the tenor of the message, and it appeared to Mercy that Jake was about to explode, but before anything could happen, White Antelope of the Cheyenne said solemnly, “Lost Eagle, you have never given us bad counsel. How soon will the meeting be?”

Before Mercy could respond, Pasquinel leaped from his seat, flung his arms in the air and shouted in Cheyenne, “Don’t listen to this old woman!” Rushing up to Broken Thumb, he grabbed him by the right arm and pleaded, “Lost Eagle is a fool. The real Arapaho want war … like the real Cheyenne.”

“What’s he saying?” Mercy asked Strunk, and the mountain man replied, “He wants the Cheyenne to ignore Lost Eagle. Wants them to go to war.”

“Jake!” Mercy cried. “You’re talking nonsense!”

The half-breed turned in a flash to confront Mercy, and cried in Cheyenne, “He comes begging you to attend his meeting. Don’t go. The Oglala aren’t going. Neither are the Pawnee.”

“Why are you trying to stop them?” Mercy asked angrily.

“Because you white men will use the meeting to steal from us … more land … more rights.”

“No, Jake. I promise you, this is to be an honest meeting. You and I will be equal. We will listen …”

Pasquinel thrust his face close to Mercy’s and said, “Equal? You will always have the cannon.”

“Jake,” Mercy said softly. “Quiet down. You know the meeting will take place. Lost Eagle has said so.”

“Him!” Jake exploded. “He speaks for no one.”

Now Lost Eagle rose to stand beside Mercy and face the three Cheyenne chiefs. In the next decades his grave, impassive face, topped by the tall-crowned hat, would be painted by four white artists and photographed by many daguerreotypists, so that the deep lines down his cheeks would become familiar across the country, and he would represent the archetypal Indian chief, the man of unshakable integrity.

Asking Strunk to interpret, he said, “We will come to Fort Laramie, and the Cheyenne will come too, and so will Jake … to help us. And when the paper is ready, Broken Thumb and I will sign it side by side.” Then he added with visible sadness, “And we shall do this thing because there is nothing else we can do.”

“Do you trust the white man?” Jake yelled at him.

“No, but we have no other choice. We must trust and hope that this time …” His voice trailed off. Then he took Mercy by the hand and said, “Tell the Great Father that we will be there.”

And as Mercy left the tipi the three crucial figures created such a vivid image that it would persist in his mind forever: Broken Thumb, conservator of the old traditions, in his role as leader, twisting his right braid with the damaged thumb of his right hand; Lost Eagle, the man who had a clear vision of what the future was to be like, standing silent, the lines of his face darkened by shadow; Jake Pasquinel, on whom fell the burden of comprehending both worlds, moving in violent agitation from chief to chief, trying to convince them of the danger to which they had committed themselves.

Mercy and Strunk rode back to the fort in confusion. They had been asked to believe that one man, Lost Eagle, could prevail against four. They were to report that the two key tribes, the Cheyenne and Arapaho, would attend in spite of the fact that Pasquinel had reported a rumor that the Pawnee were not coming.

“What do you think?” Strunk asked.

“If Lost Eagle is the grandson of Lame Beaver, as he says he is, the Arapaho will attend,” Mercy said.

When they reached the fort they found bad news awaiting them. Messengers from the Comanche, the great tribe of the south, had ridden in to say contemptuously, “White man never keeps promises. Why should we waste our horses on so dangerous a trip? And why bring our good horses among those great thieves, the Shoshone and Crow? We will not come.” And that afternoon messengers from the Pawnee reported to Captain Ketchum, “We already have peace with white man. We will not bring our horses among the Sioux.”

With the commissioners from St. Louis on their way, plus the twenty-seven wagons of gifts coming up from Kansas City, Ketchum was discouraged. On the one hand he did not relish the idea of having five or six hundred warlike Indians pressing in upon his half-fort, but on the other, he could not afford to have the proposed meeting collapse before it started, for he commanded the area, and such failure could only mean a black mark on his record. He therefore summoned Major Mercy, Joe Strunk and his lieutenants to a conference in the new officers’ quarters, and was mildly surprised when Mrs. Mercy attended, too.

Lisette Bockweiss Mercy was thirty-six, a woman of great charm, much like her mother, now dead. A tall, exuberant person, she found it easy to accommodate herself to frontier inconveniences; while her husband had been negotiating with Broken Thumb, she had been captivating Fort Laramie. Already her steadfast friend was Mr. Tutt at the sutler’s store, who confided the standard complaint about the post: “You freeze all winter, sweat all summer, and are bored all year. If I have to stay here two more years, I believe I’ll go crazy.”

“Nonsense,” she told him. “My father pitched his camp right where you’re standing, and spent a whole year with just one other man.”

“Your father!” Mr. Tutt repeated incredulously. “I thought you grew up in Boston.”

“You give me a gun and a horse,” she teased, “and I’ll bring you in a buffalo.”

Now, at the conference, she gave sound advice: “Why not send down to Zendt’s Farm to get that marvelous old Indian expert, Alexander McKeag, and send him among the tribes? He speaks all the languages and he could persuade them.”

“McKeag must be in his seventies,” Strunk protested, his pride wounded by the suggestion that some other mountain man might do the job better than he.

“Seventy or not,” Lisette said, “he’d be most useful.”

So it was agreed that Major Mercy would ride down to the South Platte and speak with McKeag and such tribes as they could conveniently reach on the way back. “I’m especially eager to get the Shoshone here,” Ketchum said. “They’ve been fighting everybody.”

But before Mercy could depart, the first good news broke. “Here come the Oglala chiefs,” shouted the lookout, and everyone watched with apprehension as they forded first the Platte, then the Laramie. In grave silence they came to the adobe fort, bowed ceremoniously from their caparisoned horses and said, “The Oglala will come.”

“Thank you!” Captain Ketchum said. He invited them to dismount and led them to his quarters in the new building. “There will be many presents,” he promised them. “You will go home with peace—peace for all the tribes.”

This phrase disturbed the Oglala. “We will not come if the Shoshone come,” they said solemnly.

“Oh, but the Shoshone must come,” Ketchum said briskly. “Translate that for them and explain why.”

Strunk did his best, stressing the indestructible brotherhood that existed among the tribes. At the end he was sweating, and the Oglala said, “If the Shoshone come, we will kill them all.”

“Oh, hell!” Ketchum groaned. “Mercy, get out of here and pick up what’s-his-name. McCabe? Ask him if he thinks the Shoshone and the Sioux can meet together.”

So Maxwell Mercy, attended by four good riflemen, rode south to Zendt’s Farm, where he found only sorrow. Three weeks before, cholera had carried off both Alexander McKeag and his Indian wife, Clay Basket.

“In the morning McKeag was as well as I am,” Levi Zendt said with obvious grief. “A chill. Nausea. Horrible death. Next morning Clay Basket began shaking. We buried them both down by the river.”

Mercy was deeply saddened by such sudden death, even though a few days before he had rationalized it to the chiefs. He walked down to the river and knelt by the circle of stones marking the graves. He said a short prayer for the quiet Scotsman who had contributed so much to the west. Without rising, he turned toward the mound that covered the Indian woman who had married Lisette’s father; he remembered her as she was when she helped run the post at Fort John, soft-spoken and capable. She had been the dutiful wife of two quite different men and had been loved by each. How many squaws, he thought as he prayed, had served in this silent manner, bearing half-breed sons like the Pasquinel brothers and lovely, dark-skinned daughters like Lucinda.

“I hope the treaty we devise will prove good to women like you, Clay Basket,” he said aloud, and on her grave he placed a clump of sage, the only flower growing in midsummer, and scarcely a flower at all.

Lucinda, now twenty-four and at the height of her beauty, volunteered the idea that Levi should go north to act as interpreter, and she showed no fear about running the farm alone. “I’ve got the children to keep me busy, and we have three Pawnee who’ll stay as long as I feed them.”

As the two men, brothers-in-law of a sort, rode west they talked, and Zendt said, “My wife’s half-Indian, and I try to understand what’s happenin’, but sometimes I’m plain confused. All day I hear white men complain about the shiftless, no-good Indian. Won’t work for a livin’. Isn’t fit to own land. And then I look at the land after the white men pass through. What they don’t want they just junk beside the trail. Their dead animals decay till the stench fills the prairies. And I say that in some things that count, the Indian is a damn sight better than the white.”

Mercy was inclined to agree, and was prepared to say so when Zendt added, “I can’t figure you out, Mercy. You could have a fancy life back east, but here you are, workin’ for this treaty like you were an Indian.”

Mercy rode in silence for some time, looking at the prairies as they swept to the northern horizon, then to the mountains emerging in the west, and finally he said, “Simple. I love this land. Loved it the first time I saw it, with you and Elly.” The name recalled painful memories and he said, “She was the soul of the west.”

Levi said nothing, and after a while Mercy snapped his fingers and said briskly, “What you say about the settlers is true, Levi. A grubby lot. But it’s them, not the goldminers, who’ll build this land. And when they do, they won’t want Indian war parties raiding through their fields or buffalo tearing down their fences. They’re going to come … can’t stop them. The enemy of the tipi is not the rifle. It’s the plow.”

“Can the same land hold a farmer and an Indian?”

“My hope is that with this treaty we’ll be able to arrange a truce. Land along the Platte for the white farmer. Empty lands like this for the Indian and his buffalo.”

“You think land like this can ever be farmed?” Zendt asked.

“Never. This is desert. And I think that if we can arrange a treaty now, rather than wage a war against the Indians five years from now, it’ll cost our government a lot less money in the long run.”

“You’re not interested in the money,” Zendt countered.

“I’m interested in justice,” Mercy said. “You and I have each been close to death, and that clears the air of petty ideas like money and advancement.”

Zendt accepted this as the statement of a reasonable man, and they rode westward into Shoshone country, where they consulted with Chief Washakie, who said that he would not take his braves into the heart of Sioux country, for the enmity between the two tribes had been marked by constant skirmishes and many deaths.

“It is this that we want to end,” Levi explained in broken Ute, a language close to that used by the Shoshone, and he explained with Mercy’s help how Fort Laramie would be neutral territory, a safe place for all the tribes to congregate.

“The Sioux will kill us if we venture onto their land,” Washakie repeated.

“It is nobody’s land,” Levi insisted. “The Cheyenne will be there …”

“They’re worse than the others,” Washakie protested.

But Mercy moved in with compelling reasons. “There will be much food at the treaty,” he said. “There will be many presents from the Great Father in Washington. Do you want to deprive your people of this bounty?” When Zendt translated this, Washakie’s face broke into a smile and he said, “If there are to be presents, we will have to come,” and on the spur of the moment Mercy thought to ask, “We? How many?”

“All of us,” Washakie said. “If it’s a decision affecting all our tribe … all of us.”

“How many?” Mercy asked weakly.

“We are fourteen hundred,” Washakie said, and by the time Mercy and Zendt left the area, the Shoshone were starting to collect food and some were folding their tipis.

When Mercy got back to Fort Laramie he found it in turmoil. One of the commissioners had reached the fort early with disastrous news. “Tell him,” Captain Ketchum directed, and the official from Washington took the major aside and recited a doleful story, whose potential for tragedy he did not even yet appreciate: “The government allocated fifty thousand dollars for this treaty. Just for the Indians. But instead of commissioning the goods in St. Louis, as we’ve done for all previous treaties, some clerk decided to buy them this time in New York. Cheaper. And in New York some other clerk decided that while we said the goods had to be in St. Louis on July 1, he felt that July 18 would be just as good, and then he found he could save a little more by using a slower railroad, so maybe they won’t get here till September.”

“I left St. Louis early,” the commissioner explained. “Had some work to do with the Sac and Fox, and when I finally got to Kansas City the presents had arrived, and I thought, ‘They’ll make it in time,’ but I was there for six days and the wagons hadn’t moved a foot.”

“What did you do?”

“Raised hell. Got them started.”

“When will they be here?”

“They’re promised for September 15. Probably get here by October 15.”

“You’ll dispatch a messenger to Kansas City. Tonight.”

“We’ve done so,” the commissioner said lamely. “Believe me, it was the contractors who are at fault in this dreadful thing. We commissioners know better.”

Mercy went to the window and pointed to the meadows beyond the parade grounds, where Indian tipis were already beginning to appear. “Commissioner,” he said quietly, “they’re beginning to gather. God alone knows how many will be there, but if they don’t have food—Look! We have only a hundred and sixty soldiers in this garrison, with a thousand more on their way …”

The commissioner coughed. “Major, I’m to advise you on that, too. The War Department has changed its mind. It needs the promised men elsewhere.” He paused and said, “Your thousand men are not coming.”

“How many are?”

“Thirty-three dragoons. Escort for the main negotiators.”

Major Mercy left the window and sat down. “You mean we have thousands of Indians congregating here—most of them braves, eager for a fight—and we have to do with a hundred and sixty men plus a handful of dragoons?”

“That’s right.”

“Oh, Jesus!” He stormed from his quarters and ran across the parade ground to the old adobe fort, where Captain Ketchum was meeting with his staff and the mountain men.

Before Mercy could explode, Ketchum asked soberly, “How many Shoshone are coming?”

“One thousand four hundred.”

Ketchum added some figures and reported, “That makes over seven thousand for sure, as of this moment, and we haven’t heard from the Crow, the Assiniboin or the Hidatsa.”

“You mean ten thousand Indians are coming to this fort?” Mercy asked.

“At least. More like eleven thousand … twelve thousand.”

“And we have a hundred and sixty effectives?”

“Plus the commissioners … the mountain men … and the dragoons!”

“Tell me,” said the commissioner, who had followed Mercy across the grounds, “how did this miscalculation occur?”

“You tell him, Zendt,” Ketchum directed, and Levi asked an Oglala chief to join them. The chief said in broken English, “White man always say ‘Chief, do this’ or ‘Chief, make your tribe do that.’ Same like Great White Father. But Indian chief nobody. He my uncle, my cousin. Nobody tell him, ‘Chief, you big man now. You run tribe.’ He run tribe just so long he do what we want. My uncle, he chief and he have some good ideas, some bad. He talk, we listen, we do. He good man, but he nobody.”

“Don’t you choose a chief?” the commissioner asked. “Well, for life?”

The young Oglala laughed. “Chief he lose teeth, he can’t bite buffalo, he finish.”

“What does this have to do with ten thousand Indians?” the commissioner asked.

Zendt replied, “Just this. You can’t go to the Oglala and tell them, ‘Send us your chiefs,’ because if the chiefs are going to talk about something that affects the whole tribe, the whole tribe will come along. A chief is not a senator. Like the brave says, he’s only as good as his teeth. Or as long as he gives sound advice.”

“What will we do?” the commissioner asked Captain Ketchum.

“I don’t know what we’ll do,” Ketchum said. “A handful of men against ten thousand Indians … no food … no gifts. But I can tell you what I’m going to do.”

“What?”

“Pray.” And as he looked out from the fort he saw the tribes from the north drifting in, and no chief rode alone. He was accompanied by his entire tribe, including the children, the dogs and especially the horses—thousands of them.

In all previous American history there had been nothing like the gathering at Fort Laramie that summer, and in the decades to follow there could be nothing to equal it, for in those later years the Indians would be dispersed, and they would lack ponies and tipis and eagle feathers for their war bonnets. But in late August of 1851 they stood at the apex of their power, and as they assembled from all points they were majestic.

First the mighty Sioux came from the northeast, the many tribes glistening in paint and feathers. They had small horses and rode them moderately well; their grandeur lay in the terrible intensity with which they pursued an objective, whether peaceful or warlike. They were the powerful Indians, willing to engage eight different enemy tribes at once, and when they came into camp they brought with them an ancient insolence. Each tribe had its special characteristics—Brulé, Oglala, Minniconjou, Hunkpapa—but all were members of the same warlike society. In their center rode their principal chiefs, who bore aloft an American flag awarded them at some earlier treaty.

From the northwest came the Assiniboin, slim men unbelievably attuned to their horses. They rode like centaurs, man and horse united in one flesh, moving together in subtle grace. To see them coming across an open prairie was to see motion and dust and waving grass frozen together for a moment, then dissolving as the procession came closer. These Indians wore no headdresses; their dignity resided in their solemn character, bred in remote canyons far from the white man.

Up the Platte came the Cheyenne, tallest of the tribes and incomparably the noblest in appearance. They rode their horses well, sat like graven images, with their right hands on their hips, and impressed the assembly with the beauty of their headdresses and the fineness of their garments. They were the nobility of the plains, the men of arrogance and self-assurance. For two hundred years they had defended themselves against any combination, and now they rode as if they possessed the prairies. In war they fought with unparalleled courage, and no other tribe in the Platte region had done more to protect the plains from desecration. Their six leading chiefs—Broken Thumb, Bear’s Feather, White Antelope, Little Chief, Rides-on-Clouds and Lean Bear—created a powerful impression of dignity as they rode into camp, for they were tall, slim, handsomely groomed, and their war bonnets were made of finest eagle feathers set in a stout gold-colored webbing decorated with quills. Each chief, because of his raiment, seemed mightier than he was; they formed a compelling phalanx as the sun struck them from the left, their bronzed faces moving in and out of shadow. Behind them, in strict military array, rode the younger chiefs, some almost naked, some in garb only slightly less imposing than their elders’. In the rear, guarding the folded tipis and the children, came the women, tall and dignified, prepared to support their chieftains in whatever decisions were reached.

From the north came the strangers, the Mandan, the Hidatsa and the Arikara, who had come only because of the assurances given by Father De Smet. They were ill-at-ease, so far south, but they came seeking protection from emigrants who were beginning to traverse their lands. They were shorter than the plains Indians but in some ways more knowing, for they had been in contact with the white man since the days of Lewis and Clark.

From the west came the strangest contingent, a small group of one hundred and eighty-three dark-skinned Shoshone, moving cautiously, each with a loaded rifle across his arms. Their arrival created a storm of excitement, and Joe Strunk shouted to the soldiers, “Watch out for trouble!”

What had happened was this. When the Shoshone left camp in western Wyoming, all fourteen hundred set forth. Their interpreter was Jim Bridger, bravest of the mountain men and one of the most canny; their chief was Washakie, who would play a notable role in subsequent history, and under the leadership of these two men they felt so secure that they traveled for some time in company with a wagon train led by white men, but as they moved eastward, a Cheyenne war party struck from the north, killing a Shoshone chief and his son.

Bridger was appalled at this breaking of an understood truce, and Chief Washakie announced that if there was to be a renewal of ancient Cheyenne-Shoshone warfare, his tribe would refuse to move any farther east. A compromise was struck whereby the women and children were sent back to camp while Washakie led the warriors of his tribe to the meeting, provided military escort were assured from Fort Laramie.

Captain Ketchum, striving desperately to maintain peace, sent Strunk and Mercy to the Cheyenne, exacting from them a solemn promise that they would not further molest the Shoshone, and White Antelope and Broken Thumb gave the assurance, and enforced it. “No war from us,” Broken Thumb promised several times, and in proof of his good will he told Strunk, “When Shoshone reach camp, we will give them a feast … and make them presents they will treasure.” Mercy shook hands with the Cheyenne chiefs and reported to Ketchum, “With the Cheyenne there will be no trouble. Broken Thumb has said so, and he keeps his word.”

“Go back and assure the Shoshone,” Ketchum directed, so Mercy rode out with Strunk, and in a mountain pass to the west they found the warriors, tense and suspicious. “This is to be a convention of true peace,” Mercy assured Bridger, and when this was translated for Washakie, that great chief said grudgingly, “We will try.” So the Shoshone, led by Washakie on a white horse, with Mercy, Strunk and Bridger at his side, rode cautiously toward the vast encampment, their horses eager to leap forward into battle if necessary, their weapons ready for the command to charge. But when they saw the multitude, and the manner in which Sioux camped by Assiniboin, they relaxed, and in the end they pitched their tipis next to those of their mortal enemy, the Cheyenne.

And from the southwest, when the others had gathered, came the poets of the prairies, the tall, quiet, hesitant Arapaho, less arrogant than the Cheyenne, less imposing than the Sioux. They were handsome men, grave of countenance and stately of mien; they were the philosophers, the artists, the ones who listened when the others spoke, but they were men and women of terrible determination, and if necessary, were willing to hazard their future and the future of their children’s children. They were not a tribe to be trifled with, these Arapaho, for they were men and women gifted with an inner dignity that had never so far been subdued. Their chiefs—Eagle Head, Lost Eagle, White Crow, Cut Nose, Little Owl—were sedate men who had come to reason with the White Father, to advise him of their problems and to seek accommodation.

When the tribes were assembled and the days of adjustment completed, the discussions were about to begin when a scout shouted from the northwest sector, “Here they come! My God, look at ’em.” Riding from the west, with the morning sun striking their faces, came an enormous contingent of three thousand Crow, whom many considered the ideal braves. They were not so dark as some of the other tribes; they were a moody people, vacillating between gravity and exhilaration, and were reported by traders who had dealt with them to be of unusual intelligence. They were a mighty nation, prowling the northern Rockies and holding tenaciously to valleys which had long been theirs.

“They know horses!” the professional soldiers cried admiringly, for although the Crow had ridden eight hundred miles, they now spurred their horses to a canter and they came across the prairie like waves coming to shore. In the forefront rode four chiefs, resplendent in costumes not known among the watching tribes: nine strings of cowries about their necks, long strands of elk bones falling from their temples, breastplates from which dangled scores of ermine tails, and most conspicuous, their hair standing upright in huge pompadours, kept in place by gum from spruce trees.

The four chiefs rode silently, looking straight ahead, but behind them came other braves looking warily from side to side, for they were entering alien land where they might be attacked at any moment. In the center of the horde rode the women, beautifully garbed, while along the flanks, on small black-and-white ponies, rode the boys nine and ten years old, fully prepared to engage the enemy.

At a signal from one of the chiefs, a band of cavalry broke from the rear and thundered to the fore, two hundred men nearly naked, riding their horses savagely. Then, to the surprise of the watchers, each man, keeping one leg wrapped about the saddletree, leaned far down on the right flank of his galloping horse, leaned under the neck and fired a salute from an old flintlock rifle.

Before the crowd could respond, the three thousand Crow reined in their horses, slowed them to a walk, and with the sun exploding on their tired and dusty faces, broke into the song of their nation—a moving chant which told of far mountains—and their voices filled the morning air.

The first decision reached by Ketchum and the commissioners was a sensible one. They convened with Mercy, Zendt, Strunk and Bridger, and asked, “How many Indians have we on our hands?”

“I’d say about fourteen thousand,” Mercy replied.

“And how many horses?”

“Maybe thirty thousand,” Zendt estimated.

“Impossible,” Ketchum growled.

“Couldn’t be less than twenty-seven thousand,” Bridger said.

“We can’t feed that many horses,” Ketchum wailed. “What can we do?”

Mercy told the commissioners, “When I visited the Cheyenne a month ago I found them camped south of Horse Creek. About thirty-five miles down the Platte. Big meadows, good grass.”

The commissioners asked Bridger what he thought of the place, but he had not come that way. Strunk said, “Enough grass down there to feed sixty thousand.” Ketchum looked skeptical.

So the decision was announced that all Indians plus a negotiating team would head southeast along the Platte to more adequate pasturage, and the vast assemblage prepared to make the move, which all approved. One hundred and seventy soldiers would go along, leaving a handful to guard the fort that night. But before they left, there was an auspicious sign. Chiefs Broken Thumb and White Antelope walked on foot to the camp of the suspicious Shoshone, where the former said, “Brothers, we have been at war too long. Our braves did wrong when they killed your people one moon past, and we offer you our friendship.”

Chief Washakie accepted the gesture and embraced the two visitors, whereupon White Antelope said, “We have come to invite you to a feast—all of you to be our honored guests,” and he led the eighty-three Shoshone across the parade grounds and into the heart of the Cheyenne camp, where a generous feast of deer had been laid out, and word passed through all the camp, Indian and white alike, that the Shoshone and the Cheyenne were feasting in brotherhood, and from each tribe certain chiefs filtered into the Cheyenne camp to see for themselves this miracle, and they arrived in time to see Chief Broken Thumb direct his squaw to rise from her place and walk over to Chief Washakie and present him with the two scalps the Cheyenne had lifted from the dead Shoshone, and as she surrendered them, Broken Thumb said, “We honored these trophies as memories of a good battle. Now we hand them back to you as proof of our lasting friendship.” And through the camp there were sounds of approbation.

Next morning the monumental procession got under way, this single largest assembly of Indians ever, riding into the sunlight, sometimes in single file, at other times six and eight abreast—Crow and Brulé, Arikara and Oglala, side by side in an amity they had never known before. The line of march, broken here and there by small contingents of American soldiers, stretched out for fifteen miles, and as he saw them go, Captain Ketchum whispered to one of the commissioners, “If those Indians got it in their minds, they could wipe us out in ten minutes.”

Fortunately, the Indians had other things in mind, for as the column approached the new campgrounds Major Mercy, riding with the Shoshone, saw bands of Sioux and Cheyenne women rushing ahead to a small plateau overlooking the confluence of the two streams, and there, without consulting the white men present, they swung into confused action, lugging in many poles and unfurling buffalo robes.

“What in hell are they doin’?” Strunk asked, and Mercy looked around till he found Jake Pasquinel.

“Our contribution,” Pasquinel replied, and the men watched in awe as the women constructed a ceremonial bower decorated with flowers, and an amphitheater area in which the formal discussions would be held. It was a creation lovely in appearance, totally Indian in concept and exactly right for the purpose at hand. As with many Indian designs, the amphitheater opened to the east so that evil spirits which might be planning to disturb the debate could escape; the good spirits, of course, would remain behind to guide the deliberations.

Two soldiers, watching the women scrambling up the poles to lash down the last buffalo robes, were astonished that they could work so fast. “Beat any men I saw in Boston,” one said.

The spirit that emanated from the discussions was as felicitous as the building in which they were held. Probably never in the history of the United States would a plenary session of any kind be convened in which such abundant good will would be manifest. The white men honestly wanted to reach a treaty that would be just and permanent. The Indians sought with open hearts to arrange land and rights in such a way that all could live honorably. The discussions of minor points were conducted, and some of the speeches which were recorded would have done justice to Versailles or Westminster.

It was a Crow chief, Brave Arm, who set the pattern for Indian comment: “Great Leader, we have ridden many days to hear your speech. Our ears have not been stopped. They have been open, and we begin to feel good in our hearts at what they hear. We came hungry, but we know that you will feed us. As the sun looks down upon us, as the Great Spirit watches me, I am willing to do as you tell me to do. I know you will tell me right and that what you direct will be good for my people. We regard this as a great medicine day when our pipes of peace are one and we are all at peace.”

Major Mercy, speaking for the United States government, said, “I am directed by the Great White Father in Washington to invite a chief from each of your nations to travel to his home to meet with him. He wants you to ride your horses down to the Missouri River, where a boat will be waiting for you. From there you will go to St. Louis, where you will see our finest city in the west. Then you will board a train and ride across our great country to Washington, where he will talk with you and give you his own solemn promise that this peace is forever, that the lands you get now are yours for as long as the waters flow and the grass shall grow. So as we talk during these last days, each tribe must be thinking, ‘Which of our chiefs do we want to send to Washington to meet the Great Father?’ And on the last day you shall tell us, and we will all start for Washington together.”

It was Lost Eagle who summed up the Indian position, and he did so with the full approval of the Cheyenne and the Sioux and the Crow, for he was known among them as a judicious man: “It is not for us to tell the Great White Father how we judged his words. You men of the army who have met with us, you commissioners who have smoked the pipe with us, you must tell him how you found us. Were we just in the discussions? Did we listen when you explained why you had to have certain trails? Did we suggest places where you could build your forts? Speak of us as you saw us during these days. And when you have done that, speak also of three things that will exist as long as the sun shines. We must have buffalo, for without food our bodies will perish. We must be permitted to ride the open prairie without the white man’s trails cutting us off from old grounds, for without freedom our spirits will perish. And we must have peace. The Crow is willing to sit here with the Sioux. The Cheyenne meet here with the Shoshone. And all assemble with the white man as their brother. We shall have peace.”

While the chiefs were occupied with such discussion, their tribesmen were engaged in lively social activity. Tribal animosities were ignored as one group after another organized feasts and conducted dances. With sophisticated sign languages, tribes swapped stories of bravado and escapades on the plains. The beat of tom-toms sounded through the day and long into the night, with as many as forty or fifty celebrations under way. In normal times such echoes would have sent a spasm of dread down the spines of white listeners, but now they attended the dances and sometimes joined in beating the drums offered them.

The only deterrent to festivity was a lack of food. The wagons were still delayed on their snail-like crawl from Kansas City, and meat became so scarce that the northern Sioux sent bands of young men into the distant Black Hills to hunt, and they returned with some buffalo, but not enough to feed the hungry mob. So the Indians took recourse in the dog feast, from which most of the whites politely excused themselves.

Once a cur had been killed, by being hanged, it was put on a fire and singed. When the skin was scraped clean, the carcass was dressed, cut up and put into a large copper kettle, where it was boiled until the bones were easily removed. Then it was flavored with prairie herbs and dried plums, becoming a succulent dish which the plains tribes considered a delicacy. After observing a sequence of such feasts, Father De Smet noted in his diary: “No epoch of Indian annals shows a greater massacre of the canine race.”

The lack of food distressed Captain Ketchum, who warned the commissioners, “If those damned wagons don’t get here soon, these Indians will begin to starve. And if I am forced to inform fourteen thousand betrayed Indians that there are no gifts, either …” He coughed. “Gentlemen, I would advise that on this night you write very tender letters to your wives.”

He dispatched Joe Strunk eastward to check on the wagons, but two days later the mountain man returned, glum. “No wagons in sight,” he said, and Ketchum instructed the commissioners, “Make your speeches longer.”

Attention was diverted from this lack of food by Broken Thumb, who assembled one hundred of the finest Cheyenne horsemen, telling them, “We shall remind the white man that while we talk of peace, we remain ready for war. And if he has plans to trick us again, let him know what waits.”

Dressed in war regalia, the hundred braves mounted their ponies and came thundering into the open space before the assembly area, where the negotiators were meeting. There they began a series of intricate and wild maneuvers. The men were armed, some with lances, some with guns, the rest with bows and arrows. Upon the hips and shoulders of each horse were painted indications of the coups that rider had won: a scalp was signified by a red hand, while a horse that had been stolen cleanly in a foray against the enemy was marked by a black horse’s hoof.

Under Broken Thumb’s direction, the Cheyenne engaged in a maneuver of which they were particularly proud. Congealing in what seemed a hopeless mass of confused horses and riders, they fired their guns aimlessly and shot arrows into the air until Broken Thumb uttered a loud war cry, whereupon one group of riders from the center pushed out to form a circular ring of protection about the whole. Then, with bloodcurdling screams, the horsemen exchanged places, those on the outside turning inward and those on the inside bursting through, each missing the other by inches, an intricate, endlessly moving design.

A principal delight of the gathering was Lisette Mercy. The Indian women were pleased that a white woman had seen fit to attend, and each day they gathered to inspect her. Lisette was a pretty woman whose light hair and many petticoats enthralled the squaws. On some days as many as a hundred would draw their fingers down her delicately rouged cheeks to see if the color would come off. They pried into her petticoats as if they were badgers inspecting a cave. And if she had permitted, they would have plucked her bald on the first day; unfortunately, some squaws had pulled out a few hairs and all felt that they were entitled to do likewise.

Lisette reacted to the encampment as only the daughter of someone like Lise Bockweiss Pasquinel could have done. Since food was scarce, she rode back to the fort to collect all the candy, tobacco and flour she could, plus as many jars of vermilion as Mr. Tutt had in his sutler’s shop. When she returned she delighted the children by drawing red circles on their cheeks. She sang old French songs and in the evening talked with the chiefs, congratulating them on how well things were going.

Because she was a Pasquinel, the Indians thought of her as their special friend, and she was often called upon to calm her half brother Jake when he agonized over the treaty provisions. When he was with her he dropped the rhetoric of war, but voiced a despair that was even more compelling.

“This hasn’t been a bargaining, Lisette. It’s been a present handed to the white man. He takes what he wants and then gives us back what is already ours. If we voice any doubts, he buys off the old chiefs with baubles and trinkets. In the end, you watch. He’ll have everything and we’ll have nothing.”

He was a tormented man: “You and Mike and I have the same father. With you—yes, and with Max too—I can be at peace, but never with the other whites. When I was a boy they gave me this scar. And don’t be fooled by Mike. He plays the clown and tries to pretend there’s some way out, but when we talk at night he knows our destruction is inevitable.”

During the closing days of the meeting, no one was busier than Father De Smet. Day and night he rushed from one group to another, baptizing babies at a rate not equaled since the days of Galilee: Indians, half-breeds, whites who had been long in the mountains, he baptized them all. He would accept people of any age or any condition, promising each an equal share of God’s beneficence. One night, following a day during which he had been especially active, he wrote a report to his superiors:

During the two weeks that I have passed in the plain of the Great Council, I paid frequent visits to the different tribes and bands of savages, accompanied by one or more of their interpreters. These last were extremely obliging in devoting themselves to my aid in announcing the gospel. The Indians listened eagerly to my instructions. They besought me to explain baptism to them, as several had been present when I had baptized several half-breed children. I complied with their request, and gave them a lengthy instruction on its blessings and obligations. All then entreated me to grant this favor to their infants. Among the Arapaho, I baptized 305 little ones; among the Cheyenne 253; among the Oglala 239; and among the Brulé and Osage Sioux 280; in the camp of Painted Bear 53.

Shortly after he baptized the Arapaho children they fell ill, and the tribe concluded that his religion was false. But among the Sioux he had enormous success, for his description of heaven, where good people go, and hell, where evil ones reside, was much to their liking, for as one chief explained, “It will be fine to be in heaven and not have to bother about white men, who will all be in hell.”

In spite of Jake Pasquinel’s doubts, the terms of the treaty were as just as could have been devised, and for once, all Indian tribes were treated fairly. An effective basis for lasting peace was achieved, one binding not only white and Indian but also each Indian tribe in its conduct with its neighbors. The government gained what it had always wanted: the right to build forts, establish roads and maintain the peace. In return, it bound itself to protect Indians against depredations by whites, while the Indians were obligated to make restitution for any wrongs committed by them.

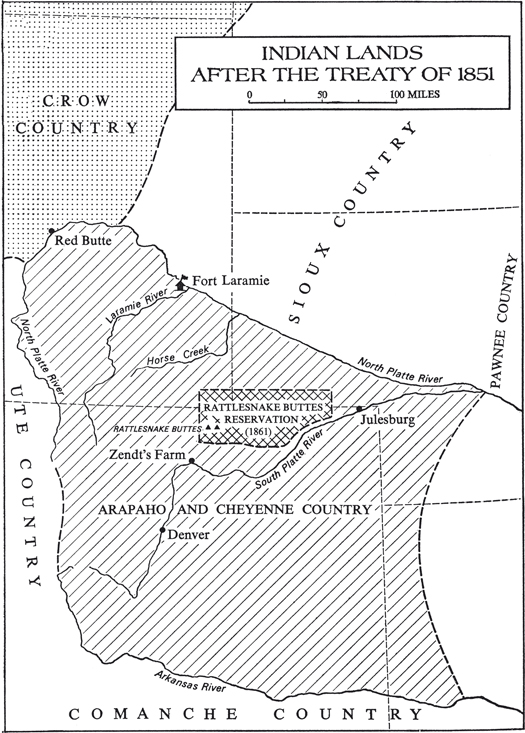

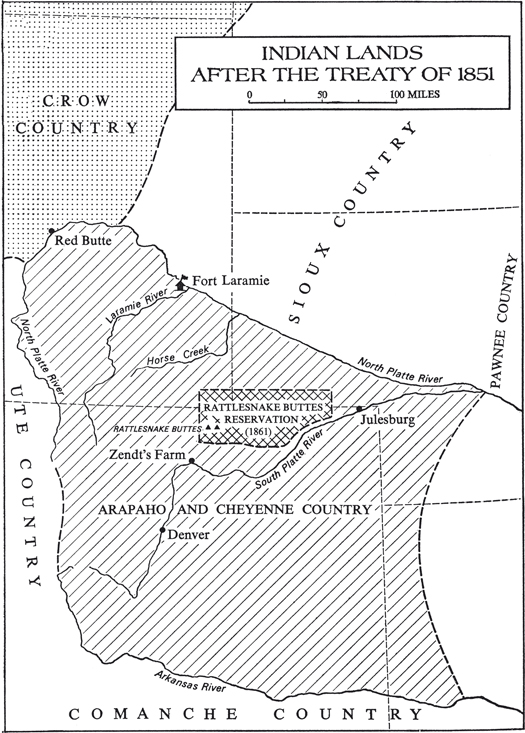

The government promised to pay the total Indian community an annuity of fifty thousand dollars for fifty years, which the government considered an honorable offer which compensated them for losses so far incurred. A notable feature was a plan whereby the prairie was cut into large segments and allocated to individual tribes, with the understanding that a hunting party from another tribe could follow buffalo wherever they went. Boundaries for the northern tribes were set by Father De Smet, who was acceptable to all, and the southern lines were drawn by Major Mercy and Levi Zendt, who awarded the Cheyenne and Arapaho a generous territory:

Commencing at the Red Butte, or the place where the road leaves the north fork of the Platte River; thence up the north fork of the Platte River to its source; thence along the main range of the Rocky Mountains to the headwaters of the Arkansas River; thence down the Arkansas River to the crossing of the Santa Fe road; thence in a northwesterly direction to the forks of the Platte River, and thence up the Platte River to the place of beginning.

This meant that 6400 Indians now owned in perpetuity some ninety thousand square miles, or more than fifty-seven million acres. Thus each Indian received fourteen square miles, or about thirty-six thousand acres for a family of four. In later years this Cheyenne-Arapaho allocation would support more than two million white men who, because they understood agriculture and manufacturing, would earn from it a good living.

Why was so much potentially valuable land given to the two tribes in 1851? Simply because both groups involved in making the treaty had false understandings of the land they were dealing with. Still prisoners of the mistaken concept promulgated by Major Mercy, whites believed the plains to be a desert which could not be farmed; Indians were convinced they were useful only for the buffalo. As always, when the significance of a natural resource is misunderstood, any land settlement must end in disaster.

Only two men refused to lose their senses in the general euphoria that marked the final days of treaty-making. The first was Chief Broken Thumb, who knew that no white man could possibly honor a treaty that surrendered lands so spacious. “Go home in peace,” he told his young braves sardonically, “but prepare for war. The treaty will soon be broken and soldiers will march out from the forts we have given them.” Seeking Lost Eagle, he called for Jake Pasquinel to translate, and warned, “Go to Washington, little brother, and humble yourself before the Great White Father, but as you go, remember that when the time comes for you to collect the promised money, there will be a different father, and when you petition him for your annuity, he will cry, ‘Who is this fool, Lost Eagle? Never saw him before.’ And there will be no buffalo and no money and no peace, and on that day you will follow me to war. As this campground now gives off a mighty stench from all of us gathered here, so, too, will this treaty.”

The other cynic was Jake Pasquinel, for when Broken Thumb finished speaking, he said on his own, “Lost Eagle, you are a great fool. When we came here Captain Ketchum promised us two things. Food and presents. Do we have either? You foolish man, they have broken your treaty before it even started.”

Lost Eagle did not know how to answer his critics. He, more than any other Cheyenne or Arapaho, had persuaded the two tribes to accept the new order, but even before the smoke had left the calumet, the first promises seemed to be broken. Still he had faith, and he said, “If a man like Major Mercy breaks his word, there is no meaning in the world. We will get our presents.”

And he moved among all the tribesmen, advising them to stay at Fort Laramie a few days longer. “The presents will be here. Major Mercy said so,” and then he went to the major and said, “Broken Thumb and the others are growing desperate. They are hungry,” and Mercy promised him, “The food will come.”

And then, after three days of miserable waiting, a scout came roaring in from the east with tremendous news: “Twenty-seven wagons! Half a day’s journey to the east!”

An escort of two thousand Indians fanned out across the plains, and when they saw the loaded wagons, their hubs dragging dust, a soaring hope rose in the hearts of all men, for this was a good omen.

It required the chiefs three days to unload the wagons and distribute the presents: tobacco, coffee so highly treasured, sugar, warm blankets from Baltimore, Green River knives, beads sewn on cardboard from Paris, dried beef, flour, jars of jam and preserves. Feasts were held at which Father De Smet said prayers and men ate till they were sick.

But the real gifts came on the final day! Then Captain Ketchum summoned the principal chiefs and told them, “The Great White Father in Washington loves his children, and when they have worked wisely with him, he gives them gifts which make them part of his family. To each of you chiefs who have signed the treaty he sends a uniform … a full uniform of his army … you are now all army officers.”

And from the bales Mr. Tutt broke forth a series of resplendent uniforms, complete with shoes, cap, sashes and swords. A captain’s uniform, “Better than mine,” Ketchum pointed out, went to each of the minor chiefs. For the major chiefs there were the starred uniforms of a brigadier general. And for Washakie of the Shoshone, Lost Eagle of the Arapaho and three others, there were the costly uniforms of major general, the epaulettes shimmering in gold.

At Captain Ketchum’s request, the chiefs donned the uniforms, and although some did not exactly fit, the new officers made a fine display, except that before they could line up for a dress review, an Oglala Sioux who had been sent south to scout for meat reported: “Buffalo on the South Platte!” and the newly commissioned officers dashed off toward Rattlesnake Buttes.

Levi Zendt followed them south at his own pace, satisfied that when they had made their kills they would bring the skins to Zendt’s Farm for trading. They did. But the profit that resulted caused no joy, for his attention was diverted by a letter from the east.

Lampeter, Penna.

The Five Zendts

Brother Levi,

I received your letter with the $12 to buy a Fordney gun, yours having been stolen, but there is nothing I can do to help you now, as God has seen fit to visit Lancaster and strike down the blasphemer who lusts after evil ways.

Four times our church directed Melchior Fordney either to marry the woman with which he was living in lust and four times he laughed at the elders. Four times too many for God’s patience.

So John Gaggerty, acting on behalf of God, took a broadax and went for sinner Fordney and chopped him down, severing his head, and then he went after the scarlet woman Mrs. Trippet and chopped her down too, slaying her in the scene of her sin. Thus does God revenge himself on the infidel.

I am shamed to report that the courts in Lancaster saw fit to condemn that good man Haggerty for what he done and they hanged him in Lancaster jail. Many good people are outraged, but the courts in Lancaster often seem to do the work of the devil.

Since Fordney is dead, I am applying your $12 against the value of the two horses you stole from me. Your debt is now $88.

Your loving brother in God,

Mahlon Zendt

When Levi finished reading, he told Lucinda, “Michael Fordney was one of the best men I knew in Lancaster.” And as he compared the gunsmith with his own brothers, he became increasingly irritated. “Damnit,” he stormed. “I have four brothers back there, and you’d think Mahlon would tell me whether they were married or had children or what.”

“You never sent him news about yourself,” Lucinda teased.

“But I’m the one away from home. He didn’t even tell if Momma is still livin’,” and he thought of the farm and the trees and the little buildings in which he had made souse and smoked hams, and he was overcome with homesickness.

Then he laughed at himself and rose and walked around the table to kiss Lucinda. “What I really wanted to know, if I told the truth, is did he marry the Stoltzfus girl? The mean pig, he didn’t even tell me that.”

And suddenly the concerns of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, seemed far away. Here in the west the future of a great part of the nation was being determined, yet his petty-minded brothers knew nothing of it. “We can draft a good treaty,” Levi growled as he wadded up the letter, “but when those Lancaster lawyers James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens get through with it in Congress, it won’t amount to much.” He saw that treaties were made by men of vision like Major Mercy and administered by mean-spirited men like Mahlon Zendt, and he saw little likelihood that any good would come from this particular one.