IF ANY SECTION OF THE UNITED STATES EVER ENJOYED A TRUE golden age, it must have been the cattle regions of the west in the early 1880s. There had been previous fine periods. The New England shipping industry in the 1840s had been magnificent, with whalers sailing distant seas and merchant vessels opening the Orient. The prosperity of cotton plantations in the early 1850s, when British markets were begging to buy, and slaves were docile and great ships from all parts of the world put in to rivers like the James and the Rappahannock to load bales, certainly deluded their owners into believing that cotton was king. And the hectic 1870s, when eastern manufacturers controlled the nation, sending their finished products out on the new railroads at huge profits, buying their raw materials cheaply from the south and west, working their labor fourteen hours a day and controlling the money market to suit their purposes, were a heyday long remembered.

But none of these earlier periods of exuberance surpassed the euphoria that settled over the west in the dazzling eighties. In those years winters were mild and cattle proliferated; investments in land produced enormous dividends; and citizens of all types saw before them a constantly expanding horizon. Like the men in earlier decades who had basked in the sun of fishing, or cotton, or manufacturing, the ranchers of the west truly believed that their golden age must continue forever, for if gold dazzles, it also blinds.

No group prospered more than those canny British who had long before spotted this part of the world as one ripe for development and hungry for investment. In later years it would be popular to lampoon these foreigners as “remittance men,” as if incompetent third and fourth sons were exiled to the west on small monthly payments to keep them out of trouble and, more important, out of sight. Many American dramatic companies, flitting from town to town on night trains, kept in their repertoire plays which made fun of these remittance men, relying on strange accents and unfamiliar customs to draw derisive laughter, but the truth was otherwise.

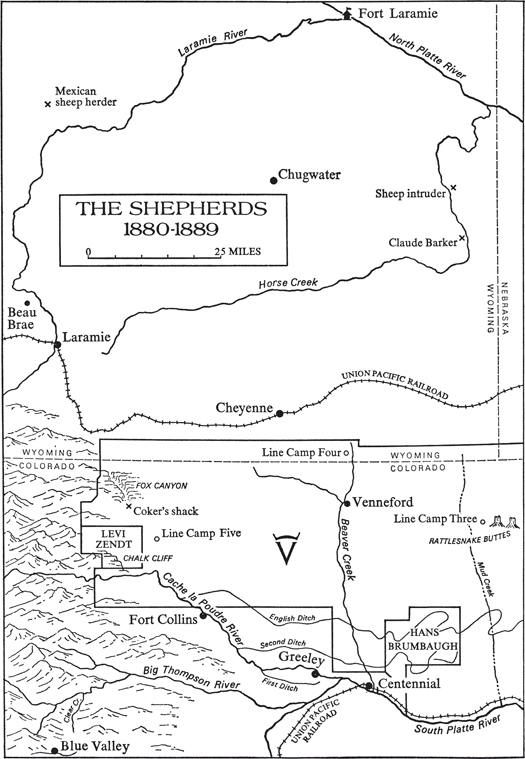

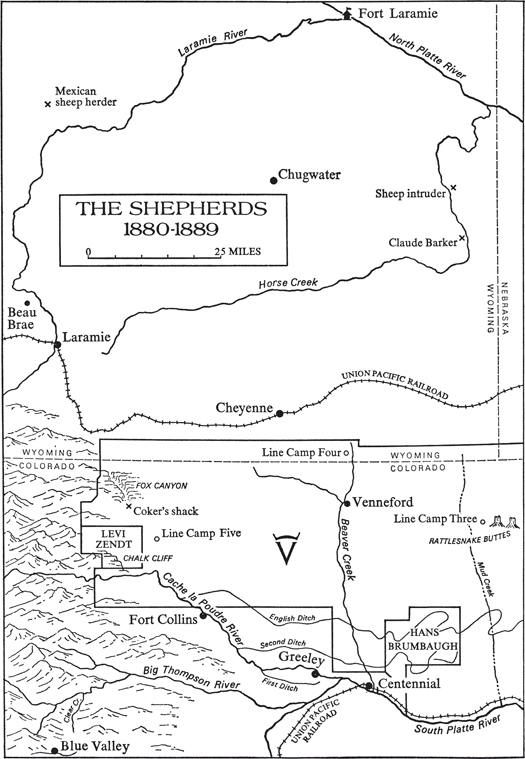

The sturdy merchants of Bristol sent out only first-class men to check on their considerable investments at the Venneford Ranch. The tight-fisted marmalade millionaires of Dundee did their best to run their great Chugwater Ranch effectively, and they did not dispatch nincompoops to do the job. In Texas the Matador Ranch, largest of all, was run primarily by shrewd investors from London, while over at Horse Creek the merchants of Liverpool were putting together a fine ranch under the leadership of Claude Barker. The most beautiful ranch of all, Beau Brae on the west bank of the Laramie River, was owned and managed by ultra-cautious Scottish businessmen from Edinburgh, and they intended to make money.

The Englishmen who supervised the railroads, protecting British investments there, were excellent people, and those who operated the mines were even better, for a more courageous type of man was required. The irrigation men were prudent, while those dealing primarily in land were bold. They brought their women with them, or sent for them after a short stay in America, and during these years along the Colorado-Wyoming border, English and Scottish patterns of life predominated. The land between the two Plattes could not properly be called an English colony, for the local political leaders were apt to be Dutchmen or tough-minded Kentuckians, but socially the area was an outreach of London-Edinburgh-Dundee-Bristol-Liverpool, and the hard-working Britishers were determined to enjoy themselves.

In September of 1880 a group of young American ranchers, educated at Harvard and Yale, accompanied Claude Barker of Wolf Pass on a ride down from Cheyenne to visit with Oliver Seccombe on a matter of some importance. Venneford was now almost a village, with sturdy buildings erected by the ranch carpenters and stonemasons. There were barns and corrals, of course, and a long, low range of sheds in which boss hands like Skimmerhorn and Lloyd worked, but the center of activity was the three-story red-stone Gothic mansion erected by the Seccombes. It was an imposing residence, resembling a castle on the upper reaches of the Rhine, and it became famous throughout the west.

Three rounded towers soared above the corners of the large house, with a four-sided battlement rising at the fourth corner. The roof contained eleven chimneys and was broken repeatedly by dormers. The ground floor was surrounded by a pillared veranda, while all doors leading into the house were made of heavy oak studded with brass fittings. It was possible to sleep eighteen guests in comfort, with four Negro servants to attend their needs.

“What we have in mind,” Claude Barker told the Seccombes, “is a club … a gentlemen’s club. We’ve selected a suitable corner in Cheyenne, and we’ll keep the membership exclusive. All of us here, plus a few others with the right kind of background.”

“What are you calling it?” Charlotte Seccombe asked.

“The Cactus Club,” Barker said.

“Oh, that’s delicious!” Charlotte cried, but her husband was more interested in the list of proposed members. They were all substantial cattlemen, except for the manager of the Union Pacific Railroad; of the initial twenty members, fourteen would be Americans, six British. Socially they were impeccable; in ranching, the most powerful.

“Will only twenty families be able to support such a club?” Seccombe asked warily. He and Charlotte were sorely overextended by the building of their mansion; true, she had put up most of the money, but he had had to sell off more Crown Vee stock to scrape up his share, and he did not relish the idea of added expense right now.

“We have a subsidiary list,” Bill Warsaw, one of the Americans, said, and he showed Seccombe forty additional names, some less glittering socially than the original but all capable of putting up large sums of money.

“These are great years for cattle,” Barker added enthusiastically. “Ranchers have money.”

“If you enlarge the list to include this second category,” Seccombe said, “we’ll come in.”

Papers of incorporation were filed on September 22, 1880, and the famous Cactus Club of Cheyenne was founded. It retained that name only briefly, for at an early meeting Seccombe proposed, “Cactus seems rather repelling. Let’s call it simply the Cheyenne Club,” and the change was made.

Its rules were rigid. They were patterned after the fine clubs in London, to which most of the British members belonged, and their purpose was to create an ambience in which a conservative cattleman could feel at ease, protected from grubby merchants, importuning businessmen and small-time farmers. Fireplaces in the various rooms were decorated with blue-and-white tiles depicting scenes and quotations from Shakespeare, and the members who occupied these rooms were expected to conform to the highest standards of decorum. Offenses which called for immediate expulsion included:

DRUNKENNESS IN THE PRECINCTS OF THE CLUB TO A DEGREE OFFENSIVE TO MEMBERS.

CHEATING AT CARDS.

THE COMMISSION OF AN ACT SO DISHONORABLE AS TO UNFIT THE GUILTY PERSON FOR THE SOCIETY OF GENTLEMEN.

In addition to these major abhorrences, the rules decreed, perhaps optimistically, that no wager of any description be made in the public rooms of the club, nor any loud or boisterous noise on the premises. In view of the ebullient nature of the younger members, and the burgeoning and heady state of the cattle industry, both a blind eye and a deaf ear became the distinguishing marks of the Rules Committee. But upon any palpable breach of social etiquette, particularly one that might reflect upon a member’s behavior toward the fair sex, the board showed no hesitancy in cutting the hair that held the Damoclean sword.

The cost of belonging to the Cheyenne Club was high, but membership ensured amenities. There were billiard rooms, games for cards, three tennis courts, access to a polo ground, a library stocked with books from Paris and London and an incomparable dining room supervised by chefs with international experience. The menus were extraordinary, and included the choicest viands and game from the region, fresh oysters from the Atlantic and fish from the Pacific, the finest cheeses and delectable fruits, a side table piled high with a Viennese pastry cook’s most mouth-watering confections, and a wine cellar that was to become the object of envy in many London clubs.

But what gave the Cheyenne Club its real significance was that from its rooms the government of the territory was dictated. Here all decisions were made relating to land ownership, the rights of irrigation, the laws for branding cattle, the regulations for banks. Wyoming Territory was a democracy; its constitution said so and it had a legislature to prove it, but the members of the legislature who mattered were all members of the Cheyenne Club, and what they decided at private caucus within the club mattered much more than what they said in open meetings of the legislature. Wyoming was a splendid, unpopulated state admirably suited for the running of cattle, and the membership of the Cheyenne Club proposed keeping it that way.

In protecting their interests they could be ruthless. Take the roundup law, for example. With nineteen-twentieths of the state an open range, cattle from one ranch could wander for a hundred miles without being detected, so when the cows had calves it was essential that some kind of general collection of animals be held, to enable each ranch to identify and brand its stock. Without this safeguard, a small-time rancher with a few cows and a flexible sense of property could round up cattle fifty or a hundred miles from any ranch headquarters and slap his iron on thirty or forty unbranded calves in no time, and after a few years of this he would wind up with a sizable herd, all reared by someone else.

“What kind of cattle do you figure is best for Wyoming?” a rancher asked one day at the Cheyenne Club.

“Without question, the Cravath breed.”

“Don’t believe I know it.”

“It was developed by Dan Cravath on his little place on the Laramie.”

“What are its characteristics?”

“Extreme fertility of the cow. Dan had only twelve cows bearing his brand, but every year they each had five calves. And this can be proved, because each year he branded sixty, sure as hell.” The members had to laugh over their wine and cigars, for all had been victimized by rustlers like Cravath.

To halt the depredations of such men, the big ranchers bullied the Wyoming legislature into passing a law without parallel. Henceforth it would be illegal for anyone except owners of the big ranches to conduct a roundup. At their roundups any calves not specifically belonging to one of the big ranches would be thrown into a common lot and sold, the proceeds to go for the hiring of officers to enforce the law. Thus big cattlemen like Oliver Seccombe and Claude Barker were legally deputized to police the range, to their own enrichment.

Now the little man like Dan Cravath, who had been running a few head on public property, would be squeezed out of business. Of course, Cravath was entitled to look on at the big roundups, but if his calves were not properly branded, they would be taken and sold. He would thus be paying the salaries of the officers whose job it was to drive him out of business, and the majesty of the state could be called upon by the big ranchers to toss him in jail if he protested.

The members of the Cheyenne Club did not abuse their privilege. A few difficult mavericks like Dan Cravath and Simon Juggers north of Chugwater were shot, but everyone knew that they had been stealing calves and it was conceded that the range was better off without them.

The members had a strong sense of stewardship where the range was concerned. They had opened it to cattle, cleared it of predators and supervised it, and whereas a distant government in Washington claimed to own it, effective ownership resided in these tough-minded men. At one hearing before the United States Senate, R. J. Poteet, the prominent rancher from Jacksboro, testified as follows:

LAMBERT: Tell us in your own words what a rancher means by the doctrine of contiguity.

POTEET: We’ve always held in Texas, and throughout the west generally, that a rancher has the right to run his cattle on any part of the open range that lays contiguous to his holding.

LAMBERT: Do you define contiguous as a matter of a mile or a hundred miles?

POTEET: Well, east and west, I’ve seen my cattle wander a hundred and fifty miles. North and south, they’ve gone halfway to Kansas, that’s better’n a hundred and sixty miles. And they did so because the open range was contiguous to mine.

LAMBERT: Aren’t you claiming, Mr. Poteet, that the range contiguous to your barn reaches from Canada to Mexico? (Prolonged laughter.)

POTEET: You know, young man, I’d never thought of it that way, but you may be right. I remember in 18 and 69 when I trailed a bunch of cattle from Reynosa in Old Mexico, across the Rio Grande and up to Miles City, Montana. Using the western trail, we traveled getting on for two thousand miles, and in all that time we crossed only two roads, the Santa Fe Trail along the Arkansas and the Oregon Trail along the Platte. We saw no fences, no gates, no bridges. We swam our cattle across so many rivers that my left point, fellow named Lasater, said, “Them critters has swum so much water, they’s growin’ webbed feet.” I guess our contiguous range did reach from Canada to Mexico, and it would be a good thing for this nation if it did so again.

Members of the Cheyenne Club quoted this testimony with approbation, for it represented their thinking.

The glory of the club was the social life that centered upon it. Charlotte Seccombe exclaimed one night, “At dinner this evening we had four peers of the realm sharing oyster stew with us. You couldn’t better that in London!”

And it wasn’t only Englishmen who graced the dining hall. The lovely Jerome sisters, daughters of a New York banker, came out from the east. Clara, the older, would marry Moreton Frewen, the Englishman who maintained his castle in northern Wyoming. Jennie, the younger, would marry Randolph Churchill and become the mother of the great Winston.

Bankers from all parts of the United States flocked into Cheyenne to look into the cattle business, and as they dined at the club and heard what the enterprising Englishmen were accomplishing, they felt an irresistible urge to invest their own funds, so that Boston financiers began to appear on British boards, and millionaires from Baltimore and fiduciary agents from Philadelphia, and in due time each of the new investors had to be initiated, to his sorrow, into the meaning of that subtle phrase book count.

Whenever John Skimmerhorn watched Oliver and Charlotte Seccombe hitch up their four bay mares for the drive to Cheyenne, he felt a pang of fear. “What’ll they buy this time?” he would mumble to himself. He did not begrudge the couple their mansion, although as an austere man he felt it pretentious, nor did he mind the extra work when delightful people like the Jerome sisters and their suitors stayed at the ranch. Indeed he told his wife, “It’s sort of fun to have dukes and earls on the place. Makes our cowboys spruce up a bit.”

What did worry him was the fact that each year Seccombe sold off more of the ranch’s basic stock. Each year the discrepancy between actual count and book count widened.

“Jim,” he asked Lloyd one autumn when the Seccombes were frolicking in Cheyenne, “how many breed cows do you estimate we have?”

“No one can say. They’re scattered …”

“How many? You’re a damned shrewd man, Jim, and I know you have your guess.”

“I’d say …” Jim stopped. He was thirty years old and most satisfied with his job. It was precisely how he wanted to spend his life, and he could look forward to many more years of employment. As he had neither wife nor children, the Venneford Ranch occupied his whole attention, and he would do nothing to endanger his position.

“You’re not puttin’ this down in a book somewheres, are you?” he asked suspiciously.

“Nope.”

“You’re not aimin’ to use it against Seccombe? Him spendin’ so much of the ranch’s money?”

“I’m asking your opinion!” Skimmerhorn snapped. “You run the cattle. I have the right to know.”

“Okay then,” Jim flashed. The two men were on tricky ground, and each knew it. As boss hand among the cowboys, Jim had to have a horseback opinion on everything, and he had one, but he did not want his information used to Seccombe’s disadvantage.

“If I was in court, properly sworn, I’d say we have about twenty-nine thousand, countin’ everything.”

“Book count says close to fifty-three thousand.”

“The book is wrong.” He was angry, both with the questioning and with the facts. For some time he had known that the books were badly inflated, and he also knew that sooner or later someone from Bristol would discover that fact, and there would be hell to pay.

“Jim, I’m on your side,” Skimmerhorn said placatingly.

“You don’t sound it.”

“What I think we should do is this. Every six months you and I will submit to Seccombe, in writing, our best guess as to the actual condition of the herd. Everything. New bulls, cows, calves, steers.”

Jim nodded.

“We’ll give them to Seccombe. What he does with them is his business. But I think we’re obligated—”

“I’ve been doin’ it,” Jim broke in, and he went to his desk and produced a ledger with honest estimates. When Skimmerhorn studied it he had nothing to say. He thought some of the figures too pessimistic and with pen and ink altered them upward, initialing his estimates.

When he was through he looked up at Jim and said, “Sometimes I think you were lucky, Jim, not to get married. She’s killing him, that one.”

Jim flushed and looked away. It was clear to him that Oliver Seccombe was in way over his head, with the headquarters mansion a monstrous weight around his neck, but never once did Jim think that Seccombe would have been better off unmarried. When he watched Charlotte greet the boss with a kiss and when he saw how proud Seccombe was to introduce his wife to their guests, he knew that whatever cost the Englishman paid was worth it. He saw Charlotte as a high-spirited woman, never afraid of skittish horses, and God knows she spent a lot of money. But she was laughter and a bright breeze and the dip of a bird’s wing. And to Jim Lloyd, without a woman of his own, these things were more important than book count.

The reassuring success Potato Brumbaugh was having with his irrigated fields should have satisfied him, for his produce was bringing premium prices in Denver, but instead it exasperated him, for during every planting season and every harvest he compared the trivial portion of his irrigated land against the massive proportion of arid land, which produced nothing, and the imbalance infuriated him.

He made two experiments. First, he tried planting his arid land, but with a rainfall of less than fifteen inches a year, all he got was a luxuriant stand of foliage in May, when the last rains fell, and withered vegetables in September, when the land lay gasping in the sun. For three successive years he spent considerable money and effort, producing nothing except the hard-won conclusion that without irrigation his benchlands were useless, except to grow native grass for the grazing of cattle.

His second experiment proved what irrigation could accomplish. Purchasing six galvanized buckets from Levi, he plowed up a small corner of his dry benchland, planted it with varied crops, then directed his wife and children to haul water all summer to keep the plants alive. It was hard work, but in September the family had melons and corn and half a dozen other things that had been waiting only for water.

“The soil is even richer than down along the riverbed,” Brumbaugh said, and the idea that hundreds of acres of productive land were going idle grieved him, and he began to brood.

He stalked along the Platte, a stoop-shouldered man in his forties, powerful and with enormous energies. Catherine the Great had been wise to import such men to her wasteland along the Volga and the later Czars had been fools to let them go, for these were the kind of men who loved the soil, who lived close to earth, listening to its secrets and guessing at its next wants. It was inconceivable to Potato Brumbaugh that nature intended those superfertile lands to lie unused, and he tried to fathom ways to bring them under cultivation.

“There’s lots of water,” he grumbled as he watched the Platte flow past. “I could pump it up.” But he had neither the pump nor the power. “We could carry it up,” but even that year’s small experiment had exhausted the resources of five strong people.

He strode along the river for so long, and with such intensity, that he became the river. He moved with it, felt it in his bones. He sensed each nuance of the flow throughout the year and slowly he began to visualize this noble river as a unit, an exposed artery with channels flowing out and back in from all directions. It held the land together and made it viable.

One day he developed an image of himself standing on dry land and pulling the river and all its tributaries up by the roots, and what was left was an empty canal, and from that conceit he began to formulate his concept of the Platte.

“It’s not a river!” he told his family with excitement dancing in his eyes. “It’s a canal, put there to bring water to land that needs it. We could go into the mountains and force the lakes to empty their water into little streams, and they’d bring the water to the Platte, and the river would carry it right to us. We could dig our own lakes, down here on the dry land, and imprison the flood water that comes during the spring and release it later as our replenishment.” He was only a peasant, but like all men with seminal ideas, he found the words he needed to express himself. He had heard a professor use the words imprison and replenishment and he understood immediately what the man had meant, for he, Brumbaugh, had discovered the concept before he heard the word, but when he did hear it, the word was automatically his, for he had already absorbed the idea which entitled him to the symbol.

“The Platte is merely a canal to serve us,” he repeated, and with this basic concept guiding him, he directed his attention to the best way to use the beneficence the river provided. For three weeks he struggled with the problem, and then by a stroke of good luck he met some farmers in nearby Greeley who were grappling with the same problem, and together they saw what needed to be done.

Well to the west of Centennial rose a river which fed into the Platte, and it bore one of the most musical names in the west, Cache la Poudre. It had been named by some French trapper who had hidden his powder there during an exploration of the higher mountains, and its pronunciation had been debased to Cash lah Pooder. Usually it was known simply as the Pooder, and during the first years of the white man’s occupancy it had been ignored.

However, when farmers entered the area the Cache la Poudre assumed major significance, for it contributed to the flow of the Platte twenty-nine percent of the total. The Platte itself accounted for only twenty-two percent of its final flow, the rest coming from streams much smaller than the Poudre, and it did not take canny farmers like Potato Brumbaugh long to realize that in their Pooder they had a flowing gold mine.

Shortly after Brumbaugh tapped the Platte in 1859 for his small ditch, Greeley farmers took out from the south bank of the Poudre a small ditch, First Ditch, that irrigated the rich lands between the Poudre and the Platte, the ones lying close to the new town. This was a puny effort, not much larger than the private ditch dug by Brumbaugh, and it did nothing for the important accumulations of benchlands to the north.

It was Brumbaugh’s idea to cut into the north bank of the Poudre, far to the west, and to build a major canal, Second Ditch, many miles long, that would follow the contours of the first bench, bringing millions of gallons of water to dry lands, including his own. Some farmers in Greeley, called upon to share in the cost, predicted disaster and refused, but others recognized the potential value of such a project and subscribed their fortunes to its building.

Through the early years it was known as “Brumbaugh’s Folly,” for it cost four times what the Russian had predicted, and some estimates for siphons and conduits had to be multiplied seven and eight times, so that the cost of throwing water upon an acre of land rose appallingly, and many advocated that the wasteful project be abandoned. Banks would lend no more money and only the stubborn courage of men like Brumbaugh, his friend Levi Zendt and a few of the religious men of Greeley kept the ditch going.

“I can’t understand them,” Brumbaugh cried in frustration as one after another of his partners withdrew. “What if it cost ten times as much as I said? Does that matter? Suppose we get water on our dry land and each acre produces thousands of dollars? Who cares about original cost?”

It was the end product that mattered, always the end product. If fearful men had set out to build the Union Pacific, they would have quit, and if cowards had been called upon to pioneer an Oregon Trail across two thousand miles of unmarked land, they would have retired. But there were always men like Potato Brumbaugh who saw not the disappointing canal but the irrigated field, and if it cost an extra two thousand dollars to build the canal, that cost was nothing—it was absolutely nothing—if from it came water that ultimately would irrigate a thousand acres for a hundred years.

It was also Brumbaugh who visualized the great fishhook at the end of the Second Ditch. The canal had gone eastward as far as practical, but it still carried a good head of water, in spite of the smaller ditches draining from it, and Brumbaugh suggested, “Let’s lead it back west,” and he encouraged the surveyors to find new levels which would permit the water to return toward its point of origin.

“He’s takin’ the water back to use it over again,” cynics joked, and when Brumbaugh heard the jest and contemplated it, he realized how sensible the critics’ idea was, and out of his own pocket he employed a water engineer from Denver to study what actually happened to water diverted from a river, and the expert, after measuring the Platte and the Poudre at many sites, concluded that whereas Brumbaugh’s Second Ditch did unquestionably take out a good deal of water from the Poudre, seepage allowed more than thirty-seven percent to drain back into the Platte downstream. The water was used, but not used up, and the engineer calculated that with more thrifty procedures, as much as fifty percent of any irrigation water would find its way back to the mother river, available for use again and again.

“It’s what I said!” Brumbaugh cried with as much joy as if the returned water were coming back to his advantage. “The whole river is one system, and we can use it over and over.” He went from one community to another, expounding his views, showing farmers how the Platte could be plumbed as an inexhaustible resource, but one shrewd man in Sterling pointed out, “You say you send half the water back, and that’s true, but you also use up half, and if we keep using half of half of half, we dry up the river.”

“Right!” Brumbaugh shouted. “We use it up as it is now. But if we build tunnels up in the mountains and bring water that’s now wasted on the other side where it isn’t needed over to our side where it is …”

“Now he wants to dig under mountains,” one of the Sterling men said, and again Brumbaugh shouted, “That’s right. That’s just what I want to do. When the Platte flows past my farm I want it to be as big as the Mississippi, and when it leaves Colorado to enter Nebraska, I want it to be bone-dry. This valley can be the new Eden.”

To accomplish what he had in mind, Brumbaugh had to devise a miracle which would have disheartened a lesser man. “What do you want to do?” a lawyer asked him one day. “Change the laws?”

“That’s exactly what I want to do,” Potato cried. And with the assistance of an impecunious but brainy lawyer from the Greeley colony, he set out to do it.

The law governing rivers, Riparian Rights, had accumulated through several thousand years of experience in countries of ample rainfall like England, Germany and France. The law was clear, and fair, and simple: “If a river has historically run first past the farm of A and later past the farm of B, A is allowed to do nothing which will diminish the flow of the river as it passes B.” This was a perfect law for the governance of the flour mill that A proposed building. He was free to lead the river down a millrace, and over his mill wheel and have the water do his work, just so long as he saw that the other end of the millrace returned to the river, so that the level when it passed B was in no way impeded. It was also an ideal law when B was a fisherman and used his portion of the river only for catching salmon; it was essential that the river keep to its proper level, and A was permitted nothing that might modify that level.

The average rainfall in the parts of England where Riparian Rights were codified was more than thirty-five inches a year, and a farmer’s big problem was getting excess water off his land. He had no reason for stealing any of it from the river, and if all lands throughout the world enjoyed thirty-five inches of rainfall a year, Riparian Rights would serve handsomely.

But what to do in a country like the drylands of Colorado, where the average rainfall was under fifteen inches a year? Here a river was exactly what Potato Brumbaugh said—an exposed artery determining life and death. To take a few inches of the Platte and lead it onto arid land, making that land blossom, was not stealing. It was something else not yet defined by law.

“We must have a new law,” Brumbaugh grumbled month after month, and in time he found in a small Greeley law office a man who saw even more clearly than he that a new land required a new law. Joe Beck was a Harvard graduate who had never been able to earn a nickel, because he was always heading off into strange directions. Brumbaugh, when he first saw Beck, knew that here was his man, and he offered him a solid fee.

“Change the law,” he told Beck. And the seedy lawyer proceeded to do so.

He devised a brilliant new concept of a river, taking most of his ideas from Brumbaugh’s apocalyptic visions: “The public owns the rivers and all the water in them. The use of that water resides in the man who first took it onto his land and put it to practical purposes. If A lives at the head of the river and has watched it flow past year after year without putting it to any constructive use, and if B lives far down the river and at an early date conceived a plan for using it constructively, then A cannot at some late date step in and divert the river so that B no longer has the water he used to have … First-in-time, first-in-right.”

It was called the Colorado Doctrine of Priority of Appropriation, and it never caught on in states like Virginia and South Carolina, with their myriad rivers and plentiful rainfall like Europe’s, but the arid western states adopted it, because they knew there could be no alternative. Rivers existed to be used, every drop of them, and they were best used in orderly procedures.

Encouraged by this victory, Brumbaugh reached out to all portions of the Platte, visualizing new ways of using the water effectively. He followed the Poudre to its source, then climbed over the mountains and down into the valleys that fed the Laramie River, which flowed north into Wyoming.

“What a waste!” he muttered as he watched the clear, icy water leaving Colorado. He saw how easy it would be to dig a diversionary tunnel—“Fifty thousand dollars,” he told Joe Beck, falling short in his estimate by two hundred thousand—and through it divert millions of gallons of water now being wasted on Wyoming drylands.

“That goddamned Russian is a menace!” the farmers of Wyoming and Nebraska growled, and they hired their own lawyers to fight him. These men told the courts, “Leave these matters to Brumbaugh and he wouldn’t allow a drop of water to flow out of Colorado.”

The accusation was just. He wanted to divert every drop of water falling west of the mountains into the Platte, then use every gallon for irrigation in Colorado. In time even the judges of the United States Supreme Court would have to wrestle with his visions, and a lawyer from Wyoming would ask the Court, “What is this man trying to do? Restructure the whole west?”

If the question had been put to Brumbaugh, he would have replied, “Yes. The only task big enough for an honorable man is the restructuring of his world.” He would not have understood the word restructure when the lawyer first threw it at him, but he would have caught the meaning quickly, for long ago he had developed the concept.

One afternoon he took his son Kurt aside and said, “Report to Joe Beck in Greeley tomorrow and start to read law.” His son, then eighteen, demurred on the grounds that he wanted to work the farm, but Potato saw the future clearly: “The man who knows the farm controls the melons, but the man who knows the law controls the river.” And it was the river, always the river, that would in the long run determine life. So Kurt Brumbaugh mastered the nuances of law regarding rivers, especially the Platte, and in time he was arguing his father’s cases before the Supreme Court.

Potato himself kept to his farm, and when he saw that the water provided by the Second Ditch was fully utilized, he combined with some far-seeing Greeley men to build a Third Ditch, but this time his vision exceeded his capacity, and he ran out of money. He and Joe Beck tried to tap every bank in Chicago and New York. “All we need is four million dollars,” Brumbaugh said disparagingly, but it was not forthcoming, so he took passage on a Cunard liner and went to London with various introductions obtained through the good offices of Seccombe. After two days of hectic oratory, Potato got his money. When he first saw the sweet, clear water running onto his land from the English Ditch, he had another idea: “In Russia on land like this we grew sugar beets. Why can’t we grow sugar beets here?” And he put in motion a whole new set of headaches for the local farmers.

In 1881 a revolutionary change came over Centennial. For the past twenty years the citizens had been calling for a railroad to build its track into the town, but they had been ignored. The Union Pacific, in its thrust westward from Omaha to bind the nation together, had pulled a rather neat trick: along its entire route only two large centers of population existed, Denver and Salt Lake City, and it managed to miss both.

From the earliest days people knew that the Union Pacific ought to build a shortcut from Julesburg along the Platte to Denver, but this the railroad refused to do. “If a man wants to travel from Omaha to Denver,” said the managers of the road, “let him ride our line to Cheyenne and take the other road down to Denver. As for shipping cattle, to hell with cattle.”

But now the rival Burlington Railroad announced plans to build a new line directly to Denver, through the vacant land well south of the Platte, and suddenly the Union Pacific burst into all kinds of energy. Starting from the parent line at Julesburg, the rails were thrust westward at a galvanic rate: ten, eighteen, twenty-two miles a day. Skilled construction crews who had learned their jobs elsewhere, the Irish and the Chinese, moved in with practiced skill and fairly skimmed the tracks across the prairie. Like a great centipede the rails jumped westward.

When the railhead reached Centennial, citizens watched the laying of tracks with as much excitement as if it were a circus, and three local girls ran off with members of the construction gang. Hans Brumbaugh’s younger daughter, a flaxen-haired woman of twenty-three, was more prudent, and when the surveyor attempted to seek her favors, she insisted upon marriage.

The tracks ran along the north bank of the Platte, and formed a fine, solid edge to the town. The railway station became the focus of civic life, with several trains a day in each direction and a telegraph office from which messages of grave import could circulate throughout the town. Social life centered on the Railway Arms, the large hotel which the railroad built adjacent to its station.

On land donated by Levi Zendt, architects who had built other such establishments along the Union Pacific swept into town and in a few breath-taking months erected a major hotel, with many rooms, three different dining areas and a long bar. It cost the railroad $18,000 to build, and in 1883 alone it made a profit of $31,000.

Centennial was now linked to all the major cities in America, and the Venneford Ranch could ship its cattle direct to whatever market it deemed best. Boxcars of goods could be imported, and few men or women in town would forget the excitement that arose when word flashed that a cattleman named Messmore Garrett was bringing in four boxcars of steers which he proposed running on the open range.

“There is no open range,” men said. “Venneford has it all.”

“They don’t own it. It’s open if’n this guy Garrett can get to it.”

“How in hell’s he gonna get to it, answer me that.”

“He wouldn’t be comin’ if’n he didn’t have an idea on that score.”

The telegram said simply:

BAGBY CENTENNIAL

ARRIVING THURSDAY FOUR CATTLECARS OF STOCK

MESSMORE GARRETT

CARY MONTANA

So when the freight pulled in on Thursday afternoon, most of Centennial was at the station to see who would be handling the Garrett steers. The train whistled twice east of town, then chugged in and came to a halt. Mailbags were thrown down and messages exchanged, but the citizens focused their attention on four boxcars, from the first of which stepped a slim cattleman in his late thirties. He wore the customary large hat, but even so, women could see that his hair was slightly graying. His eyes were deep-set and commanding, and he walked with a firm step as he strode forward, extending his right hand and introducing himself. “I’m Messmore Garrett. Who’s here to help unload my stock?”

Watchers looked at the various experienced cowboys and were astonished when none of them stepped forward. Instead, Amos Calendar shuffled to the front, wiped his nose with the back of his sleeve and said, “I’m Calendar.”

“Bagby hire you?”

“He did.”

“Glad to see you. Let’s drop those chutes.”

Calendar went to one of the cars, which had now been detached from the rest of the train, and threw a chute into position. Someone inside the car slid the door open, and from a crowd of cowboys came the awed cry, “Jesus Christ! Sheep!”

Down the ramp ran hundreds of woolly sheep, dirty from their long ride, inquisitive and hungry. One ram ran to where the cowboys stood, and they recoiled from it as if it were a rattler. “Get away from me!” one of the cowboys yelled, almost as if he were a woman, but the ram pushed on, brushing against the cowboy’s leg. As it pressed onward, the man gave it a mighty kick in the head, all the time cursing as only a cowboy could. “The damned thing touched me,” he told his mates with obvious revulsion.

By nightfall word had sped across northern Colorado and well into Wyoming, carrying the dismal news that sheep had entered the cattle country. John Skimmerhorn, appalled at the event, cabled Bristol:

PERKIN EIGHTEEN HUNDRED SHEEP INVADED OUR RANGE STOP ADVISE IMMEDIATELY

SKIMMERHORN

The answer was brief: GET THEM OFF. In fact, it was the only sensible answer that could be given, for it was an established fact that cattle and sheep could not use the same pasture.

“The sheep is a filthy beast,” cowboys averred that night as they tried to get the smell of the new arrivals from their nostrils. “A steer won’t touch grass that sheep have walked over. The woollies leave a smell. Christ, I can smell it now.”

“What’s worse,” another said. “The sheep crops the grass so close, a cow can’t get nothin’ for two years after.”

“It ain’t only that,” the first cowboy said. “The sheep has a sharp hoof, and he cuts the grass below the stem, right down into the root.”

“Mostly, though, it’s the smell,” a third man said. “My uncle could walk into a restaurant and if they’d cooked mutton within three months, he could smell it. Cattle ain’t dumb. They know that smell kills.”

So the war began. In self-protection against the woollies the cattlemen felt they had to drive the sheepmen off the range, and they were ruthless in their determination. At the Cheyenne Club the big ranchers compared notes, and some thought the way to protect the range was to shoot the sheep from ambush, but others reported success from clubbing them to death after dark. One rancher along the Laramie River got his cowboys to herd the woollies over a precipice. “We killed more’n a thousand that way,” he said.

But others preferred poisoning. “Usin’ saltpeter or blue vitriol on the grass,” a Chugwater man said, “takes care of a hell of a lot of sheep and you don’t lose any cattle.”

Claude Barker, a notably serene man, said little about the problem, but when sheepmen invaded his range, two of them were shot, leaving one survivor to drive the remnants of the herd back north.

On the Venneford Ranch the problem became acute. Oliver Seccombe was on his way to England when Messmore Garrett arrived with his first four loads of sheep, and decisions had to be left to Skimmerhorn, who used every device he could think of short of murder to dislodge the sheep. He had no success. Calendar moved the first flock onto the range east of Rattlesnake Buttes, and Buford Coker, the South Carolina Confederate, led a large bunch to Fox Canyon northwest of Line Camp Five.

Skimmerhorn was restrained in dealing with the two intruders because he knew them both, had served with them on the Texas cattle drive. He liked Coker and had a grudging respect for Calendar’s ability to protect himself. “One thing I’ve got to warn you about,” he told his cowboys at a meeting convened to deal with the trespassers. “Those two men know how to shoot. Calendar especially isn’t going to be scared by threats of gunplay. You behave yourselves.”

The well at Fox Canyon was poisoned and quite a few of Coker’s sheep died before he could rescue the others. Calendar’s flock was attacked by a running pack of savage dogs who had been maneuvered into the area by men on horseback. Calendar coolly shot most of the dogs, but only after they had done much damage. Grass in the draw which was used as a corral was set afire from all directions, and some two hundred sheep burned to death, but Calendar and Coker stuck to their job, and Messmore Garrett shipped in more sheep.

He was a resolute man. At the local bank, where the tellers found it repugnant to serve him, he deposited ten thousand dollars and let it be known that he wished to buy land for a sheep ranch, his own headquarters, that is, while he ran his sheep on the public domain.

“It’s a goddamned disgrace,” the banker said at a dinner held by cattlemen in the Railway Arms. “That range has been out there for a thousand years, and the only person who has cared for it in all that time is the cattleman. Legally I suppose it belongs to the government. But it’s our range. That damned Messmore Garrett better not try to buy land from me.”

The cattlemen were especially outraged when employees of Garrett rode in to the land office and signified their intention of taking up homesteads. “You know it ain’t for them!” they exploded. “It’s just Garrett tryin’ to get aholt of some land. Sure as hell, the day they prove it up, they’ll turn and sell to him. The law oughta stop them.”

Three members of Garrett’s family applied for homesteads, but their papers were lost. They applied again, but a lawyer intervened on behalf of the local citizenry to fault one of the applications, and the two others had to be sent to Kansas City for verification. They, too, were lost.

Garrett made no public complaint. He hired a Denver lawyer who had fought such cases for years, and with glacierlike pressure that expert tied up some parcels of land from which Garrett could, although with difficulty, organize and run his sheep ranch.

The big breakthrough came when the lawyer filed papers at the courthouse for the purchase of two thousand acres of land at Chalk Cliff from Levi Zendt.

The whole pressure of the cattle industry fell on poor Levi, and his store was set on fire, the second time he had suffered this incendiary form of debate. The fire was extinguished, not by the fire company, whose members refused to fight any fire on property belonging to a sheepman, but by Garrett and his friends. Next day the Clarion reported:

The store of Levi Zendt, who seems to prefer the company of sheepmen to that of honest men, caught fire. Unfortunately, it was put out. We remind our readers who have the welfare of this region at heart that this is the same Levi Zendt who protected the Pasquinel brothers when they were burning and murdering along the Platte. People from Pennsylvania seem to require a lot of learning.

Zendt ignored both the fire and the news report, but when a group of cowboys wanted to know how he could sell decent land to a sheepman, he told them, “Indians sold me that land, to help me get started. I allowed Venneford to use it, to help them get started. I sold Brumbaugh other land, to help him get started. And you’re damned fools to ask such a question.”

They reported this at the ranch, and Skimmerhorn rode down from headquarters to reason with Levi. “It’s criminal to bring sheep onto a cattle range,” the foreman argued. “They destroy. They use up. They’re no better’n a bunch of hoofed locusts.”

Levi countered that in his life—he was now sixty-two—he had seen many new ideas evolve and always men said they destroyed the world as it had been. “Maybe the endless range that you know, John, is a thing of the past. Maybe you ought to buy some of that barbed wire I have and fence your land and know what you’re doin’.”

“But, Levi, you own shares in Venneford. You’re cutting your own throat.”

“I don’t think too much of your cattle shares, John.” And onto the table he tossed the contract he had made with Messmore Garrett, giving him land for his sheep. “Fact is, John, I’d like to sell my Venneford shares. If you know anyone who wants to buy them.”

Skimmerhorn did. Next day Jim Lloyd appeared at the store and said, “Mr. Zendt, I hear you got some Venneford shares for sale.”

“I sure do.”

“I’d like to buy ’em.”

“You’d be a lot smarter buyin’ sheep shares. I could get you some.”

Jim drew back, aghast. “I’m a cattleman. I run cattle.”

“If you know what you like, stick to it,” Levi said. “You can pick up my Venneford shares at the bank.” Then, lowering his voice, he said, “Lucinda and I have been wondering—do you ever hear anything about Clemma?”

“Never,” Jim said.

“No more do we,” Levi said. Then, briskly: “Jim, you’d be doin’ this part of the country a service if you warned your cowboys to leave Coker and Calendar alone. Those men have only so much patience.”

“They’re not my cowboys,” Jim protested. “The troublemakers are comin’ down from Wyoming.”

“Better warn ’em to stay home, Jim. There’s gonna be trouble else.”

The warning was to no avail, and three nights later someone got among the Calendar sheep and clubbed more than a hundred to death, breaking their heads open with violent, shattering blows.

In the golden summer of 1883 Chief Lost Eagle, then a frail old man of seventy-three, had his third and last portrait made standing beside a President of the United States. In 1851 he had stood with Millard Fillmore following the great treaty of Fort Laramie, and ten years later he had been photographed with Abraham Lincoln. Now Chester Arthur was vacationing in Yellowstone Park, in an effort to bring the needs of that noble area to the attention of the nation at large. Such a trip into wilderness was a daring venture, requiring the services of seventy-five cavalrymen, many teamsters and scouts, and one hundred and seventy-five pack animals. In passage the President proposed to stop over at the Indian reservation in northwestern Wyoming.

There he met the famous Shoshone chieftain Washakie, who had a grievous complaint, lodged with vigor and ancient contempt: “Why did the Great White Father allow the Arapaho to trespass onto my reservation?”

President Arthur looked to one of his aides for explanation, but none was forthcoming, and Washakie, now a man in his eighties, continued: “You know the Arapaho eat their dogs. You know we have fought them for a hundred years.”

Here an aide informed the President that the Ute, of which the Shoshone were a segment, had indeed fought the Arapaho for a century, and it was true that the Arapaho did eat dogs. “Disgusting,” the President said.

The protest continued for some time, after which a scout was found who could explain: “The Arapaho have no right to be here … none at all. They were expelled from their reservation in Colorado and taken to the Dakotas, but they didn’t like it there.”

“Who required that they like it?” the President asked.

“So when food ran out, they were allowed to come down here.”

“They should be sent back,” the President snapped.

“But they’ve been moved around too much, sir.”

The President agreed to listen to the Arapaho side of the story, and Chief Lost Eagle was brought to see him. He presented a pathetic figure, a withered little old man in a tattered army uniform, with a big bronze medal about his neck and on his head a silly high-crowned hat, a turkey feather sticking up from the band. He was bowlegged from years in the saddle and he spoke in a high voice.

“We have traveled far,” he said, “and at last we have a home. We wish to stay.”

“What’s the medal?” Arthur asked, and General Phil Sheridan, a man who hated Indians and who had coined the classic phrase “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” moved forward to inspect the bronze.

“President Buchanan,” Sheridan reported, repressing a snigger.

The entourage moved in, each man wanting to be photographed with the funny little Indian, and he posed for some time, realizing that his appeal to the Great Father had not been taken seriously. “If I could speak with the President again,” he pleaded, but the cavalrymen kept pressing in to have their pictures taken, and by the time Lost Eagle was able to break away, the President had gone.

“Over here! Over here!” the scouts were calling in Shoshone, and Lost Eagle, who did not understand that language, was left alone until a soldier started pushing him. “Over here, Grandpa,” and he was maneuvered into a group containing Washakie and the other Shoshone.

“Arapaho,” one of them muttered, but now the photographer was shouting at them to remain very still, and he had barely taken the picture when a wild shout arose from a distance and a group of young Indian braves galloped onto a large open field, where President Arthur sat under a canopy. It looked as if the young men were going to attack the President, but at the last moment, from another corner of the field, a company of cavalrymen, led by a boy blowing a bugle, rushed forward to engage the Indians in mock battle. There was a furious discharge of blank ammunition, with horses whinnying and eleven Indians, trained for the purpose, falling off their horses and sliding in the dust as if they had been killed. After ten minutes of shouting and fine horsemanship and an infinity of firing, the brave cavalrymen drove the Indian savages from the scene and saved the President.

The young Indians who participated were congratulated by both President Arthur and General Sheridan for their fine riding, after which they were allowed to get mildly drunk. Senator George Vest, of Missouri, and Robert Lincoln, son of the late President, agreed that it had been a memorable display, and then the last of the joking cavalrymen insisted upon being photographed with Chief Lost Eagle, and again he patiently posed while the group made fun of him.

Of all the men who were photographed that day, the chief’s life had come closest to the American ideal, closest in observing the principles on which this nation had been founded. He was immeasurably greater than Chester Arthur, the hack politician from New York, incomparably finer than Robert Lincoln, a niggardly man of no stature who inherited from his father only his name, and a better warrior, considering his troops and ordnance, than Phil Sheridan. His only close competitor was Senator Vest, who shared with him a love of land and a joy in seeing it used constructively.

But the group laughed at him, would not listen to his petition, and failed even to realize that he was presenting them with a grave moral problem, not of much magnitude, but perhaps of greater intensity for that reason. By the time the presidential party left Wyoming, Chief Lost Eagle was dead.

The coming of the railroad affected the white man as profoundly as the horse had changed the Indian. For example, in the early summer of 1884 Levi Zendt was confounded by a telegram which the stationmaster handed him:

ARRIVING UNION PACIFIC FRIDAY AFTERNOON TO STUDY INDIAN TRIBAL LAW

CHRISTIAN ZENDT

In confusion he showed the message to Lucinda, who asked, naturally, “Who’s he?”

“I don’t know. I had a brother Christian. He bought cattle and was so stupid he never heard of an Indian, let alone law.”

“Could it be his son?”

“Nobody ever told me who has sons.”

Lucinda decided it must be one of Levi’s nephews, most likely a son of Christian. He was probably studying law somewhere and had caught on to some fancy idea about Indians. Having suggested this, she became grave: “Should I leave while he’s here?”

“No!” Levi exploded. “Why should you?”

“I am Indian.”

“That’s what he’s comin’ out to study. Cutthroat Indians. Let him see a real one.”

“What about my brothers.”

“Look!” He pulled his wife by the arm. “When they kicked me out of Lancaster my family thought me worse than your brothers. I was lower than a murderer. They’ve got no right to be put off their feed by Pasquinels.”

“Does your family know that I’m your wife?”

“I haven’t told ’em.”

“I think I’d better go to Denver.”

“You stay here. It’s time they knew.”

So when the afternoon train chugged in from Julesburg, with many of the townfolk at the station, for its arrival was still a novelty, Levi and Lucinda were there to greet Christian Zendt, whoever he was. Down the steps, carrying a small carpet suitcase, came a tall, blond, square-faced boy about twenty-three years old.

“You must be Uncle Levi,” he said brightly, with an unpretentious grin. “And this is Mrs. Zendt.” Then he looked at her closely and asked, “Are you a real Indian?” And when she nodded graciously, he cried, “This is better than I’d hoped for. It’s truly wonderful!”

All the way to the farm he talked like a magpie. Graduated from Franklin and Marshall. Yes, son of Christian Zendt, but he was dead now. Three years ago. Enrolled in the law school at Dickinson. Yes, the other three brothers were still living, all with kids. His mother had been one of the Mummerts of Paradise …

“The old wagon makers!”

“The same.”

“Did Mahlon marry?”

Yes, but very late. He courted the Stoltzfus girl for about fifteen years. He was afraid to marry, right out like that, and she was afraid to lose him, because he was the only man her age left, and she lost her looks and every Tuesday and Friday they stared at each other across the market, she in her stall selling baked goods and he in his selling meat and both families getting richer, and finally the three brothers got together and said he had to marry her, it was unfair otherwise, and he took to his bed with fear, so Christian and the other two brothers went to the Stoltzfus girl and proposed for Mahlon, and they were married, “And when I last saw them, they stood side by side in the meat stall and one of the Stoltzfus boys had taken over the bakery.”

“Any children?”

“One every year for five years.”

The more Levi and his wife saw of this ebullient young man, the more they liked him. He sat enraptured as she told how her uncles had tied buffalo skulls to their backs and had danced in swirling dust until the thongs broke through their back muscles. She told also of her brothers and how they had escaped the massacre, and Levi shared the pain when Christian broke in: “Dear God, Aunt Lucinda! You don’t mean Skimmerhorn set up the guns on purpose and mowed them down?” She said that was exactly what she meant.

He had a wonderful freedom from false nicety. “Tell me about the deaths of your two brothers. We hear a lot about them back east. I never dreamed they were my uncles!”

She laughed bitterly, then told how one had been hanged, how the other had been shot in the back by Frank Skimmerhorn, and how Levi, defying local hatreds, had buried them both. They talked a good deal about tribal law, and Levi was astounded at how much his wife knew. Her knowledge was not codified—that would be the task of trained men like Christian—but it hung together, and for the first time Levi understood that Indians were governed by customs as rigid as those which bound the Mennonites of Lancaster County.

One night Lucinda told Levi, “It’s not proper, a young man like this talking with us all night. He ought to be meeting some of the girls.” When Levi saw how easily this youngster of twenty-three handled the young ladies and with what grace he bandied their flirtations, he recalled his own barbarity at that age.

When the time came for Christian to return to Dickinson, four Centennial families with daughters sought to give him farewell parties, and he accepted, kissing the girls and their mothers goodbye. At the station he told Levi, “You should visit the family. I’m sure they’d welcome you.”

“I’m not so sure. I’m still the outcast.” He was standing with his arm about Lucinda as he added, “Don’t tell them I married an Indian. They wouldn’t understand.”

“I never see them.”

“You don’t?”

“No, when I wanted to go to college they raised Cain, Mahlon worst of all. Even my father ridiculed me. To hell with them all.”

When the train chugged in from Denver, Lucinda kissed her nephew goodbye and said, “Come back. Come often. Lots of people in this town would be pleased to see you, Levi and me most of all.”

He swung onto the train, blew kisses at the girls—and returned to his studies. Three times that winter Lucinda brought up the question of Levi’s going back home for a short visit. Each time he said, “Not unless you come too,” and she replied, “Lancaster’s not ready for an Arapaho Indian.”

So he dropped the matter, but she raised it a fourth time: “A man ought to see his kin. Levi, you can’t imagine how you perked up when Christian was here. You have a right to know how the trees are doing.”

Often through the years he had wondered how those stately trees had grown, and whether the barn still sat with its hex signs among the meadows, but before he could respond, she made another comment even more compelling: “I cannot forget that when they left Jake Pasquinel’s body on the gallows, you stepped forward to claim it, because he was my brother. From that day I would have walked through hell for you, Levi. A man ought to stick with his kin.”

She bought him a large suitcase and some new clothes. She purchased the ticket, Centennial to Omaha to Chicago on the Union Pacific. Change stations at Chicago for Lancaster on the Pennsylvania. She took him down to the station an hour early and introduced him to others who were going as far as Chicago. But she would not accompany him.

The trip was so uneventful. He could not believe that he had once struggled for a half year to cover the same distance, and on Wednesday morning when the train pulled into the cavernous station at Lancaster, he was awed by the change, but then he saw his three bearded brothers waiting for him, and time seemed not to have touched them. Mahlon, still tall and dark, had acquired neither weight nor congeniality. He looked as if he were there to collect the remaining eighty-eight dollars Levi owed him for the stolen horses. Jacob looked pretty much the same, and Caspar, who did the butchering, was the powerful man he had been forty years ago. To the farmers of Lancaster the passage of years meant little; they tended their business and allowed others to worry over intrusions like the Civil War and financial panics.

The brothers remarked on Levi’s lack of beard and congratulated him on having been able to manage a train trip all the way from Colorado. They piled him into a wagon pulled by two handsome bays and off they went to Lampeter, where Levi discovered that Hell Street was quieter now, but as they approached the ancient lane and the tall trees, he saw that the farm was unchanged. There stood the towering barn with its colorful hex signs and the reassuring pronouncement:

JACOB ZENDT

1713

BUTCHER

The lovely trees were more stately and the little buildings were just as he had left them. He wondered how many miles of sausage and acres of scrapple had come from that red shack since he left.

“We have a stall in Philadelphia now,” Caspar explained. “We take the train to Reading Terminal. Very large business.” Levi was pleased to hear the Pennsylvania German accent again: werry larch busy-niss.

At the house, so small when compared to the barn, Levi met the Zendt wives, and there was Rebecca Stoltzfus, totally changed. She was plump and white-haired and very stolid. Only the cupid’s-bow mouth was the same, and in her expanded face it looked rather ridiculous. He held out his hand and she shook it formally.

“Things are good at the market,” she said.

“Who’s runnin’ the bakery?” he asked.

“My brother,” she said.

The Zendt women had a traditional family dinner waiting, a display of food that staggered Levi, who recalled the many years he had lived on pemmican and beans. The table and the groaning sideboards contained a full seven sweets and seven sours, eight kinds of meat, three kinds of fowl, and six kinds of cookies, including the ones whose memory had tormented him when he was starving: crunchy black-walnut made with black molasses.

He wondered if any people were entitled to so much food, so much of the world’s goodness. And as he surveyed the farm and saw the ample supply of water and the infinity of trees and the lush grass where one acre would support a cow, he was struck with how easy life was in Pennsylvania and how brutally difficult in Colorado, where you had to dig a ditch twenty miles before you could tease a little water onto your land.

It was the trees that moved him most deeply. He loved to walk in the woods or sit at the picnic area in the grove: Yes, that’s a hickory. How many of them I chopped down to fuel the smokehouse. And the oaks, they haven’t grown an inch in forty years. And the good maples and the ash and the elm. We had a treasure here and never knew it.

On Friday evening the children found him sitting beneath the trees, tears in his eyes. “You feeling tired, Uncle Levi?”

“I was thinkin’ of the time I needed a tree to save my wagon,” he told them. “And I had to walk many miles to find one.” They knew he had to be lying.

At family prayers Levi was astonished, there could be no other word for it, by the minute detail with which Mahlon told God what to do. At each grace the tall, acidulous man would direct God’s attention to evildoers, to men who had stolen money from the bank, to girls who were misbehaving, and Levi began to understand why so much violence had been permitted in Colorado. With God kept so busy in Lancaster prying into petty problems, how could He find time to watch over real crimes like those of the Pasquinel brothers and Colonel Skimmerhorn?

From time to time the family dropped discreet questions about his experiences in the west. They knew that the girl he had abducted from the orphanage at gunpoint had died.

“Killed by a rattlesnake,” Levi said without inflection.

“Any children?”

“She was about to have one when she died.”

“Did you remarry?”

“Yep.” He let it go at that.

By Saturday it was obvious that Levi Zendt was not happy at the family farm and that his brothers were ill-at-ease with him. He did not belong to the family, and no one was grieved when he announced that on Monday he would head back for Colorado. “Chicago, then St. Joseph, Missouri. There’s a stage that runs out of there along the old road that Elly and I took in the Conestoga …”

“That would be interesting,” Caspar said frigidly.

At Sunday dinner the Zendt women put on a lavish display, not only to send Levi west on a full stomach but also to welcome Reverend Fenstermacher—son of the older preacher—on his regular eating visit. Levi dreaded the prospect, but the minister proved much different from his self-righteous father.

“Forty years ago, when I bought my rifle from Melchior Fordney, he boasted that you could fire one of his percussion guns three times in two minutes,” Levi said.

“That was my brother. He died at Antietam.”

“Was the war hard on Lancaster?”

“On boys like my brother … very hard.”

Fenstermacher offered a grace marked by a deep sense of God’s benign presence and the fellowship that sprang from it. At the end he pointed to the table and said to Levi, “Your family intends that you shall not forget the bounty of Lancaster.”

Levi put his fork down and said, “It’s strange, but when we were starving on the plains I never once thought of a dinner like this. I thought only of special things. The bite of sour souse, the rich stink of cup cheese, and black-walnut cookies. Does the souse still sell well?”

“Better than ever,” Mahlon said, “especially in Philadelphia. Caspar’s wife makes it now, same way you did.”

Then, for some perverse reason, Levi decided to show his family their sister-in-law. Coughing, he produced a photograph of Lucinda, one in which she looked very dark. He said, “You haven’t seen my wife,” and passed it to his left. He could tell who was holding the picture by the look of shock that came over each face. Finally the Stoltzfus girl said, hesitantly, “She’s very … western.”

“She’s an Arapaho.”

“What’s that?” Caspar asked.

“Indian. She’s half-Indian.”

This was greeted with gasps, which Levi ignored, directing his attention to the meats. From somewhere came the question, “What’s her name?”

“Lucinda McKeag.”

“Doesn’t sound Indian. Sounds Scotch.”

“That wasn’t her real name. McKeag picked up her mother when her father died, and she went along.”

There was enough in that sentence to preoccupy the Zendts for some moments, after which Levi volunteered, “Her real name was Pasquinel.”

This information was greeted by silence, during which Reverend Fenstermacher knitted his brow. At last he asked quietly, “Was she related to … Wasn’t there a Pasquinel family we read about?”

“There was. The old fellow was a mountain man. His sons were known as the Pasquinel brothers.”

“Those?” several voices asked almost tremulously.

“Yep. Lucinda’s brothers were a mean pair. They hanged one. Shot the other in the back.”

“The half-breed murderers?”

“The Indians suffered more murders than they committed, but the Pasquinels were killers.” Levi helped himself to apple butter and preserved cherries. “I had the unpleasant job of cutting the older boy down from the gallows. At the time I thought it was merciful he was dead, but reflectin’ on what we did to his tribe, I’m not so sure we hung the right people.”

Reverend Fenstermacher coughed, but Levi was started and nothing, not even food, could stop him. He told of the Indian fights, of the years of drought, of locust swarms, of the gold-mining camps. Every incident he referred to was alien to the Zendts, and in a way ugly, but as he unfolded the epic of life in the west it began to acquire a certain grandeur, and the very magnitude of it made them at least listen with respect.

One comment on the sun dance reminded him of young Christian Zendt, and prompted him to say, “You ought to get that boy back here. He may prove to be the best Zendt of all.”

As the meal ended, Mahlon said unctuously, “Reverend Fenstermacher, since it may be a long time before we see our brother again, would you please give our family a special blessing!” The reverend, having anticipated such an invitation, had certain things he wanted to say.

“Dear God, Who watches over us, You have heard me say a hundred times in church, ‘God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform.’ Nothing in my experience has been more mysterious than the manner in which You took Brother Levi west and placed him among the Indians and gave him an Indian wife and Indian brothers. You chose him from among the five Zendt brothers to do Your work on the frontier, and he has done it well. He has been our emissary, and we have all been remiss in not sending him money to aid him when he needed it. We have kept our love from him. We have not even bothered to acquaint ourselves with what he was doing. God, forgive us for our indifference.

“But Levi was in error, too. He did not share with us his adventure in settling the wilderness. He did not report to us either his struggles or his victories. Especially was he afraid to bring his wife Lucinda here to visit with his family, afraid lest we embarrass her because she was Indian. Does he think we are so poor in spirit? When he returns home let him tell his wife that we send her our love, that we know her as our sister and that our home is her home, now and forever. Does he think that we do not know tragedy also? The Civil War that struck so many families here was just as deep a sorrow to us as the Indian wars were to him. We are all Your children, God. Truly, we are brothers in Your family and as we share our tragedies so we share our triumphs, and it is love that binds us together. Amen.”

There wasn’t much the Zendts could say after that. It was obvious that any preacher who would insult the richest Mennonite family in Lampeter, and at their own table, had no bright future in the Lancaster area, and the goodbyes after dinner were restrained. Levi went down to the grove, to sit among the trees, and it occurred to him that just as the Arapaho had dragged buffalo skulls through the dust, punishing themselves, so white men dragged behind them enormous skulls of another kind. The Indians were smart enough to allow their burdens to rip free; the white man seldom did.

The return to Lancaster had been unbearably painful. He had not said a dozen words to Rebecca Stoltzfus, the girl who had changed the direction of his life; he knew no more about her now than when he stepped off the train. He had discussed nothing of gravity with Mahlon, who seemed as distasteful now as he had forty years ago. He had not even been gracious enough to ride in to Philadelphia to see the family stall in Reading Station, because he had been so wrapped up in his own memories that he didn’t really care what was happening to the family.

It had been a terrible mistake to come here, and he left without being able to improve relations with his family in the way Reverend Fenstermacher had hoped. He was not sorry to go, and the Zendts were even less sorry to see him board the train.

At St. Joseph, Levi changed to the stagecoach, which would take him slowly west; and as the ferry carried them across the Missouri, he relived the journey of forty years ago. He felt he had been correct in leaving Lancaster, for now he knew that nothing had changed in the intervening years: he had found no significance other than tables piled ridiculously high with food. And as they chugged along, everything he saw added to his excitement—the muddy river, the black boys along the waterfront, the creaking ferry, the brooding threat of Kansas, the highway west. How he wished that Elly and proper Captain Mercy and bright Oliver Seccombe were with him now, just starting out with their teams. Even crafty Sam Purchas—he would want Sam too.

But after the coach was well into Kansas and had climbed past the Presbyterian mission, it came to the Big Blue, and Levi called to the driver to stop, and he climbed down to inspect this puny creek, this mere trickle of water in August, and he was aghast to think that this miserable pencil line across the landscape had once been a forbidding torrent where he had nearly lost his wagon and his wife.

It was incredible. Memory was playing him false. Then the image of the buffalo skulls returned, and he visualized himself dragging across the prairies his painful burdens of remembrance. But his robust sense of reality reasserted itself, and he began to laugh at himself. “I missed the whole point!” he cried. “My brothers were uneasy because they feared I was comin’ back to claim my share of the farm. It’s part mine, but let ’em keep it.” He continued laughing. “Never once did they ask about the dinosaur. Biggest thing ever discovered in the west. Must have been in the Lancaster papers.” He shook his head and chuckled. “They’d have asked about the dinosaur if it was something good to eat.”

When he climbed back into the coach a man from Nebraska, staring at the river, said, “Hell, you could spit across that,” and Levi laughed and told him, “Not in the spring of ’44, my friend.” And heavy skulls tore from the sinews of his mind, and he told the man, “Right now, though, you’re right. A good man could spit across it.”

When Levi reached Centennial, neighbors persisted in questioning him about the east, and at first he rebuffed them, but finally he spoke for all westerners when he said, “Back east, wherever you look, you see something. The world crowds in on you. I can’t tell you how homesick I got for the prairies, where a man can look for miles and not see anything … not feel crowded. Out here the human being is important … not a lot of trees and buildings.”

Other people were also returning from their travels. When Oliver Seccombe came home with his wife after their six months in England, he found Venneford Ranch in trouble. On the extreme outer edges, over toward Nebraska, squatters were building sod huts on the open range which had long been preempted by Crown Vee cattle. Along the Platte, immigrants from states like Ohio and Tennessee were taking out formal homesteads, as if by doing so they could gain access to the range. Committees were actually visiting the ranch headquarters to see about buying ranch land for the building of small towns.

“We need towns in this state,” they argued, and Seccombe told them, “Not on our land you don’t.”

Worst of all, the sheepmen led by that damned Messmore Garrett were more and more digging in and running their sheep on what had always been considered cattle territory. The situation was becoming intolerable, and on his first day home Seccombe ordered Skimmerhorn and Lloyd to ride out with him to warn Garrett’s men: “Vacate or suffer the consequences.”

They rode east to where Amos Calendar had parked his lonely wagon—bed, commissary, refuge from storms for months on end—and it was some time before they could find the lean Texan. He rode toward them with his rifle across his saddle and grunted a meager hello to Skimmerhorn and Lloyd.

“I’m Oliver Seccombe,” the Englishman said. “You’re trespassing with your sheep. This is cattle country.”

“It’s open range,” Calendar said.

“I’m warning you to get your sheep out of here.”

“I’m stayin’ till Mr. Garrett tells me to move.”

A dog now ran up, a collie-type with white and black hair. “Good-looking dog,” Seccombe said. “You ought to get him out of here, where he’ll be safe.”

“Rajah’s safe anywhere,” Calendar said slowly. “Long as I got my Sharps.”

The ranchers were getting nowhere with this difficult man, but Seccombe was determined to deliver the warning: “If you don’t move the sheep, Calendar, we’ll move them for you.”

“You tried that before and failed.”

Seccombe flushed. “What do you mean by that?”

“Them gunmen who tried to kill me didn’t come from Brazil.”

“Are you suggesting that I …”

“I ain’t suggestin’ nothin’. I’m simply tellin’ you that if any of you sonsabitches fire at me, I’m gonna fire back.”

“Let’s get out of here,” Seccombe said, spurring his horse and starting west.

They headed for Line Camp Four, among the piñons, and as they rode Skimmerhorn said, “I better explain Buford Coker, Mr. Seccombe. He’s a hot-tempered Confederate from South Carolina. He’s not like Calendar at all. As you’ve seen, Calendar likes being alone. Coker don’t. He’s gone in to Cheyenne and spent a lot of time at Ida Hamilton’s House of Mirrors, and last time I saw him he’d persuaded one of the girls, Fat Laura …”

“I’ve heard of Fat Laura,” Seccombe said.

“Well, you’ll find Fat Laura in the sheep wagon with him. Or maybe in a shack. Coker’s building himself a shack at Fox Canyon.”

“Building!” Seccombe exploded. “That’s cattle country. We let him build, we’ll have half the sheepmen in the west …”

Coker was building. He and Fat Laura had hired two men to come down from Cheyenne and build them a substantial shack at the mouth of Fox Canyon. It was not elegant, but it was sturdy, and when Seccombe saw it he wanted to shout, “Skimmerhorn! Have that thing torn down!” for it was a visible warning of what would happen across the range if corrective steps were not taken, and quickly.

At the door of the new house stood Fat Laura, a Virginia woman in her late twenties and obviously a graduate of Ida Hamilton’s academy. In her teens she must have been pretty in the buxom, bucolic way that cowboys appreciated, but ten years of hard life and constant movement from one brothel to the next could not be disguised, and the accumulation of forty pounds gained through the only activity she really enjoyed had made her a slattern. She was six inches taller than Coker and thirty pounds heavier, and why he had associated himself with her remained a mystery.