THE TROUBLE WITH SUGAR BEETS, A MAN COULD NEVER FIND anyone to do the thinning.

For example, Potato Brumbaugh had learned that it was prudent to deep-plow his fields in late October, so that winter snow would water them and winter freezing aerate the compact soil and break up the clods. In March a brisk sequence of disk, harrow and drag would have the land moist, firm, level and ready to seed. And at this point the job looked easy.

Unfortunately, the seed of the beet was both small and unreliable. It would have been all right if Brumbaugh could plant one seed here and another twelve inches down the row, with a reasonable expectation that each would germinate and produce its one-pound beet, but that he could not depend upon, for the seeds were capricious; one would germinate properly and the very next one, alike in every outward aspect and nurtured in identical soil, would not.

So on April 25, when the likelihood of frost had diminished, he had to plant his sugar beets the way a housewife plants radishes: he sowed the seed heavily along the whole length of his rows, using about twenty-four times as many seeds as he really needed. This heavy overplanting was necessary to offset high losses in germinating and the early death of weak plants that did germinate; insects, weather and carelessness could cause losses as high as seventy percent.

On May 26, therefore, he had in his carefully tended rows not one plant every twelve inches, the way he wanted, but a continuous line of young plantlings, eight for every one he intended keeping. If all eight were allowed to mature, they would be so crowded that none would have space or food to produce a usable beet. So he had to do what the housewife did: take a long-handled hoe and chop away seven out of every eight plants, leaving one strong plant to produce its beet.

Blocking and thinning it was called, and tedious work it was, for it required a person to move slowly over the entire field, hour after hour, hacking away at the unwanted plants. No owner had the time to block his whole acreage by himself, for the job had to be done within a brief, specified period, lest the unwanted plants grow so tall that their roots would suck away the nutrition required by the one which had been selected to produce the beet.

A lot of men and women with hoes were needed to block a field properly, and they had to be reliable, for they were required to work fast and to exercise judgment.

“Some farmers block their plants ten inches apart,” Brumbaugh instructed the Italian immigrants who appeared by the trainload to work the beets, “but I like mine a little farther apart, about a foot. Keep this stick with you to show how far apart the plants should be.”

The Italians were excellent workers, with a sense of soil and a quick comprehension of what Brumbaugh wanted. They understood when he said, “I’ve been chopping beets so long, I can hack out the unwanted ones with one swipe of the hoe. More better you use two chops … like this.”

The Italians worked well, but wouldn’t stay on the job. They didn’t like transient work or the loneliness of sugar-beet plantations. Time and again a fine crew would spend one spring with Brumbaugh, but come late summer they would hear about the steel mills down in Pueblo and off they would go for work where they could have their own little house in an Italian community with its priest and a good restaurant, and the sugar beets would see them no more.

“Giuseppe,” Brumbaugh pleaded with the head of one family, “why can’t you stay north with me?”

“Ah, I like to be with the others. Some singing. A priest you can rely on. No, I’m going to Pueblo.” And off he went, leaving Brumbaugh with no one to block his beets, or thin them, or pull and top them at harvest.

German immigrants were arriving in New York about this time, so the beet farmers around Centennial paid the train fare for sixty families, and they were some of the best help Brumbaugh ever had. He enjoyed talking with them in German, even if they did laugh at his Russian pronunciation, but they posed a serious problem: they loved the land, and within two years of arriving at the Brumbaugh farm, they wanted land of their own, and left to grow their own beets.

The next experiment had a more fortunate outcome … at first. Brumbaugh, at his wits’ end, proposed to a group of his sugar-beet neighbors, “Why not the Russians? When I lived on the Volga they knew more about sugar beets than anyone.” So the community imported numerous German-Russian families—Emig, Krakel, Frobe, Stumpf, Lebsack, Giesinger, Wenzlaff—and when these sturdy men and women got off the train at Centennial they took one look at the spacious fields and knew intuitively that they had found a permanent home.

They were splendid people, hard workers, thrifty, intelligent. Ten minutes of instruction told them all they required about their new job, and when Brumbaugh saw them whisking down the rows, chopping out unwanted beets with one swipe, he knew he had solved his problem.

Not quite. The Volgadeutsch yearned for land even more than the Germans, and within eighteen months each family had begun to pay installments on a farm of its own, and with sorrow in his big square face Potato Brumbaugh watched them pack up their few belongings and leave.

He was cooperative. When Otto Emig informed him that he was buying the Stupple place, Brumbaugh said, “Karl, that farm’s too small to work profitably. You ought to pick up fifty more acres while you can.”

“I have no money,” Emig said.

“I’ll lend you some. I don’t want a good farmer like you to start on too small a plot.” In this way he helped some dozen of the Russians get their foothold, hardy men and women with large families who would lend much character to the northern plains. Strasser, Schmick, Wiebe, Grutzler—they all owed their mortgages to Potato Brumbaugh and they were grateful, but still Brumbaugh found himself with no one to block his beets.

He imported Indians from the reservation and they were all right during the spring when they could work with horses, but when it came time to hoe, they vanished. He tried impoverished white men drifting westward from states like Missouri and Kansas, but they stole, got drunk and trampled the young plants, leaving six-inch gaps in one row, fifteen in the next. They seemed determined to prove why they had become derelicts and why they would remain so.

“Get them out of here!” Brumbaugh thundered. “I’ll block the beets myself.” But when the useless drifters were gone and he attempted to farm the fields, he found that whereas he might be able to block a large field at the age of seventy-seven, he could certainly not take the next step and thin it too.

Thinning was the brutal part, the stoop-work. It required a man to bend over hour after hour, demonstrating judgment, accuracy and the ability to endure prolonged discomfort. Again the trouble lay in the seed, for instead of a single seed, beets have a cluster of from three to five enclosed in a hard, rough shell. When planted, the cluster produces not one plant, but three or four or five. The shell is too hard to be broken and no way has been found to encourage one of the plants to grow and the others to die.

“What you have to do,” Brumbaugh told his various workers, “is go down the row that’s been blocked and look at each of the bunches we’ve left standing. You’ll see that each bunch is really three or four or five plants. Each could produce a beet, but if they all did, none of the beets would be worth a nickel. So what I want you to do is leave the biggest plant and pull the others out. And be sure to get the root.”

He could not avoid this imprecision: “Guess the good one and kill the others.” In the end, it had to be a matter of personal judgment. With his practiced eye he could pick the strong plant, and had he the strength to thin his entire acreage, he would produce the best crop in Colorado, but this crucial task he had to leave to others—to the guesswork of untrained hands. He used to shudder when he saw them ripping out the good plant and leaving in its place another that could never produce a big beet.

“Can’t you see which the good ones are?” he used to rail at the thinners in the early days. He stopped when he realized that they couldn’t see, that to them one plant looked pretty much like another, and he began to wonder if the sugar-beet industry could survive when it had to depend upon such unreliable labor.

Yet he was gentle with his workers, for he knew that thinning beets was among the most miserable jobs on earth. Hour after hour, bent double, eyes close to the earth, back knotted with pain, knees scabbed where they dragged along the ground. He had great respect for a man, or more likely a child, who could thin beets properly, and he brooded about where he would find his next crop of workers.

It was his son, Kurt, now in his prosperous forties, who solved the problem. Kurt had become Colorado’s leading legal expert on irrigation; in Washington he had defended the state before the Supreme Court and in Denver had helped draft the state laws governing the use of water. Because of his knowledge he had been the logical lawyer for the sugar-beet financiers to look to after they had collected the large amount of capital required to launch Central Beet, for they intended to construct a many-tentacled company, with factories in all areas. In time this combine would dominate the western states.

A sugar beet was worthless until a sugar factory stood nearby. A mature beet was a heavy gray-brown lump of fiber hiding a liquid which with great difficulty could be made to yield crystallized sugar. In the late eighteenth century chemists in Germany, where there was no sugar cane, perfected an intricate method of making the beet surrender its sugar, but the industry had staggered along until Napoleon Bonaparte, faced by the loss of cane sugar due to the British blockade, decreed, “Let us have beet sugar!” and the French discovered how to provide it.

Because the beets were so heavy, and transporting them so costly, it was obligatory that the factory be near at hand, and it fell to a committee of three men in Central Beet to determine where the factories should be located. An engineer, a soil expert and Kurt Brumbaugh, as the irrigation man skilled in finance, visited every likely area from Nebraska to California, choosing sites. They made some mistakes, and lost thousands of dollars in the process, but mostly they chose well, and never did they select a better site than on that day in the spring of 1901 when they announced, “Our biggest plant in northern Colorado will be erected this summer in Centennial. A plant capable of slicing nine hundred tons of beets per day. When finished, it will be able to handle the entire crop from this area.”

The E. H. Dyer Construction Company of California moved in its skilled engineers and the Union Pacific started building a spur down which the beets would arrive and along which the bags of sugar would depart. It was a massive operation, located east of town on Beaver Creek, for the extraction process required much water.

When the factory was completed in 1902, and the first wagonloads of Potato Brumbaugh’s beets were delivered, the slicing began, then the carbonation process, then the crystallization. Soon across Centennial drifted the rich, distinctive smell of wet-pulp fermentation. Some citizens thought it acrid or even putrescent, and after a couple of seasons of sugar-making they left town, unable to stand the new odors. But most found it to be the smell of progress, a decent, earthy aroma of beets turning themselves into gold.

Messmore Garrett, who welcomed any scientific addition to the community, observed, “It’s an earthy smell … organic … crisp. I like it.” In time, most people living in Centennial grew to welcome the yearly arrival of the sugar smell. Charlotte Lloyd said, “It sort of cleans out the nose, like the smell of good manure. I feel better when the campaign starts.”

Mature sugar beets were harvested during October and early November, for they had to be out of the ground before the heavy frosts of late November. This meant that they began arriving at the factory about the first of October, with the slicing under way every day till the middle of February. This period was known as the campaign, and it was an exciting time in the beet country, for not only did the rich smell permeate the countryside, but the top ten farmers of each district were announced, and to be one of the top ten in Centennial was a coveted accolade in American agriculture.

Each farmer’s yield per acre was determined by taking the total weight of beets delivered to the factory, less the weight of dirt he had allowed to cling to his beets, less the weight of excess tops he had failed to chop off, divided by his total acreage. Toward the end of each year the officials at Central Beet announced their findings, after which the ten winners were photographed. Their pictures would appear in the Centennial paper, suitably captioned: “Our Top Ten, They Can’t Be Beet!” And then these leaders were feted at a large banquet in Denver.

In 1904 it was suspected that the Centennial championship would go either to Potato Brumbaugh, who had won the two previous years, or to Otto Emig, who had some good acreage along the Platte east of town. Brumbaugh growled, “If Emig wants to win, he’s got to do better than seventeen and a half tons to the acre.” Some listeners considered this boastful, and Emil Wenzlaff challenged him: “You never made seventeen and a half, Potato, and you know it.”

“Wait till you see the figures,” Brumbaugh said confidently. He was an old man now, and when he grinned at his competitors, his mouth was yellow and wrinkled at the corners. The other farmers could not believe that a man his age could have thinned so large a portion of his crop, for he was thickset, and bending must have been painful. However, since he could find no competent help, he had had no choice but to tend the fields himself.

As he compared notes with others who hoped for the championship, he invariably ended with one question: “What are we going to do about help?” He listened as the other farmers proposed various solutions: “More Germans, but this time get the dumb ones who don’t want to send their kids to school.” “Why not try the Indians again? They’re not doing anything up there on the reservation.” “What we need is someone who enjoys doing stoop-work and doesn’t want to buy his own farm.” But where to find such workers?

Otto Emig, whose beets looked the best of the lot, argued, “Central Beet would never have spent so much money building that factory if they didn’t have a plan in mind. They’ll find us workers somewhere.” The solution to this problem was to come from a man not associated with the factory.

Jim Lloyd, at Venneford, had been delighted with the arrival of the sugar factory, because it provided an alternative source of feed for his white-faced cattle. It was pulp that was important to him.

“I love to smell that pulp come out the chute,” Jim said. “I like the way my Herefords go for it.”

When the heavy sugar beet was sliced and pressed, and its precious liquid drained off, there remained a moist, grayish mass called pulp. It was an excellent fodder for cattle; especially when mixed with heavy black low-grade molasses, another by-product of the sugar process.

“Pulp and molasses!” Jim Lloyd said admiringly. “Whenever I cart a load of that up to the feed yards, you can almost see the Herefords spreading the news. They’d walk miles for it.”

Jim was therefore much concerned about keeping the Centennial factory operating, and he knew that without reliable help for the local farmers during the blocking and thinning seasons, the whole thing was going to go bust. Germans, Indians, Italians, Russians, poor whites—none of them was a solution. “We’ve got to find someone who can be trusted to thin properly and who’ll stay on the job.” He decided to talk to Kurt Brumbaugh about an idea he had.

In December heady news spread through Centennial. Otto Emig had apparently performed a miracle.

As soon as it became apparent that some farmer stood a chance of winning the championship, experts from the factory went to that man’s farm with a steel chain to measure the exact number of acres he had harvested, and the results at Otto Emig’s farm indicated that he had set a new record: “Seventeen point seven tons to the acre!”

Emil Wenzlaff carried the news to Brumbaugh. “That’s what he done, Potato.”

“He’s a good farmer,” Brumbaugh admitted grudgingly. He could not believe that Emig had done so well on those bottom lands. He must have fertilized each plant by hand.

Potato had enjoyed many successes in his life and it would have been generous of him to concede victory this year to Otto Emig, but he was a fearful competitor and at seventy-seven needed victory as keenly as he had at twenty-seven.

And then the final figures were released! In a long article in the Clarion, with photographs, it was revealed that Potato Brumbaugh had set a new record! Seventeen point nine tons to the acre, a figure so high the other farmers could scarcely believe it.

Of his victory Brumbaugh said, “The right soil, the right water, the right seed, this Platte Valley land can grow anything.”

“And the right thinning,” Otto Emig said generously.

“Where will we get our thinners next year?” Potato asked.

In late February 1905 Kurt Brumbaugh sprang his surprise. He announced that following a suggestion provided by Jim Lloyd, and as a result of extensive investigation, Central Beet had come up with the ideal solution to the problem. Its field men had located the world’s best agriculturists, men and women—and children, too—who could grow fuzz on a billiard ball. One hundred and forty-three of them would arrive on March 11 prepared to make the Platte Valley hum.

All the beet growers of the region were at the station when the train pulled in, and it was a day memorable in Colorado history. Down the iron steps leading from the cars came a timid, frightened group of men, women and children. They were small, thin, shy and dark. They were Japanese, and not one of them spoke a word of English, but the waiting farmers could see that they were a rugged people, with stout, bowed legs and hands like iron. If any people on God’s earth could thin sugar beets properly, these were the ones.

A representative from the Japanese consulate in San Francisco stepped forward, a bright young man in dark suit and glasses, and he said in precise English, “Gentlemen of Centennial and surrounding terrain. These are all trusted farm families. You can rely on them to work. In consultation with Mr. Kurt Brumbaugh of Central Beet, we have assigned them as follows.”

And he began to recite that extraordinary series of lyric four-syllable names: Kagohara, Sabusawa, Tomoseki, Yasunori, Nobutake, Moronaga. As he did so, the families stepped forward, shoulder to shoulder, and bowed low from the waist, even the smallest children. Each family was then assigned to one of the Russian farmers, a curiosity which the editor of the Clarion duly noted:

Yesterday at the Union Pacific station a miracle happened, an amazing event which could have occurred only in the United States, where people of diverse races and religions live together in perfect harmony. A group of one hundred and forty-three sons and daughters of the Sun Goddess arrived in our fair city and were promptly assigned to work with our finest Russian farmers, and this at a time when Japan and Russia are locked in mortal combat on the other side of the world. Since the Japanese speak no English and no Russian, they have placed themselves in the hands of their worst enemies. But such is the miracle of America that no one present at the station yesterday had the slightest fear that the local Russians would in any way treat their Japanese workmen poorly or with injustice.

The editor was right. This was a most happy union of Japanese who knew how to farm with Russians who loved the soil, and during that war-torn year, peace and amity reigned along the Platte, primarily because the Japanese were the best sugar-beet workers in the world.

To Potato Brumbaugh were assigned the Takemotos: father aged twenty-seven, mother aged twenty-five and strong as a Hereford, daughter aged seven, son aged six, son aged three. They rose before sunrise, had a meal of rice plus whatever they could find to go with it, and went out into the beet fields with the wife carrying a small basket containing cold rice balls, each with a sour pickled plum in the center, and a bucket of cold tea. They worked till dusk with a tenacity that Brumbaugh had not seen before.

Mother and father would take their hoes and start blocking, each to his own row. Behind Mr. Takemoto crawled his elder son, thinning the clumps. Behind Mrs. Takemoto crawled the seven-year-old girl, thinning her row. All day the baby watched the workers, pulling away any half-rooted plants they had missed. Since the parents could block a little faster than the children could thin, at the end of each row the elders would put down their hoes, drop to their knees and thin back down the row till they met their children. At each such meeting there would be a brief pause while the parents brushed away dirt from the round little faces or said something reassuring. Then it was back to the hoes and the thinning.

From March through October, there was no spoken communication between Potato Brumbaugh and this remarkable family. In pantomime he would show them what he wanted; after that they took charge, and by mid-September it was pretty clear that he stood a good chance of winning the championship again.

He told his son, “Kurt, the best thing you ever did for Central Beet was to bring in the Takemotos. One of them is worth six Russians. No wonder Japan won the war.”

And then he noticed two chilling things. The Takemotos were obviously acquiring money, and they were looking at land. How could they get hold of that much money? When Brumbaugh had allowed them a small plot by the river, he expected they would grow a few vegetables for their own use; instead, they had cultivated the land with extreme frugality, depositing on it all the Takemoto sewage, and were producing so many fine vegetables that Mrs. Takemoto was peddling the surplus through the village.

Where did they find time to do this? From sunup to sundown they worked in Brumbaugh’s fields, but they rose an hour early and in the darkness tended their vegetables, and in the moments after sunset they did not sit around resting after that day’s work. All five of them were down by the river, watering and hoeing and cultivating. When Brumbaugh indicated in sign language, “In America we don’t use human manure,” Mr. Takemoto replied in excited gestures, “In Japan we do, long, long time.”

“Well, quit doing it here!” Brumbaugh indicated, and they did. Each morning when they came to work and each night when they went home, the Takemotos carried a bag in which they gathered horse manure, or any other that had fallen, and their garden flourished.

On Saturday afternoons and Sundays, Mrs. Takemoto, accompanied by her son, who was picking up a few words of English, trailed through town, offering her enormous vegetables for sale and accumulating cash, which the family deposited at the local bank.

“They come in here every Saturday morning,” the banker told Brumbaugh, “and without saying a word they plop their money down and I give them a slip. He checks it and she checks it and then they check it a third time with me, and then they write something in their gobbledegook and they bow and go out.”

What really frightened Brumbaugh was that on Sundays the Takemotos, all five of them, inspected farms in the region. He saw them first one hot day in September, the father kneeling in the soil of the old Stacey place, the mother checking the irrigation gate, the children playing with stones. In August they were up at the Limeholder place at the end of the English Ditch, inspecting the soil and the water. Later he saw them at the abandoned Stretzel farm, beyond Otto Emig’s excellent land, and in October, when the beets were topped and delivered and Brumbaugh was on his way to another championship, the ax fell.

Takemoto and his wife, and the three children, appeared at the Brumbaugh ranch, bowing low. Mrs. Takemoto, who apparently handled the money, placed a bankbook before Potato, and by means of gestures easily understood, indicated that they had decided to buy the Stretzel farm. They sought help from him in arranging the legal details.

Brumbaugh was seventy-eight that October and he feared that he had not the strength to break in a new set of help or till the fields himself. He judged it terribly unfair that this family had stayed with him less than a year, and he needed them more now than he had in March. He was tired, and there had been frightening spells of dizziness. A prudent man would quit the farm and the irrigation board and retire to Denver to live in ease, but to Potato this was simply not an option. He loved the soil, the flow of water, even the sight of deer in the far fields eating their just share of the crops. He had taken this once-barren land and made a garden of it, plowing back year after year the beet tops which helped keep it strong. Some farmers, eager for the last penny, sold their beet tops to Jim Lloyd as forage for his Herefords, but Brumbaugh would not consider this. “The tops belong to the soil,” he told young farmers. “Plow them back and keep the land happy. Cart manure from the ranches. Everything depends on the soil.”

It had been Brumbaugh who devised the clever system of importing boxcar-loads of bat manure from the recently discovered deposits at the bottom of Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico. This new-type fertilizer was dry and compact and easy to handle. It was also preternaturally rich in mineral deposits; where it was used, crops grew.

Because of his own preoccupation with manure and its relationship to land, Brumbaugh had followed carefully the efforts of the Takemotos to enrich their soil, and whereas he had not always approved of their methods, he did applaud their determination. Therefore, when Takemoto sought his help in finding a farm for himself, Brumbaugh was ready to assist.

He loaded the family into a wagon and drove them to town. The banker, whose wife had for some time been buying vegetables from Mrs. Takemoto, said judiciously, “These people have a fine reputation, Potato. Look like top-quality risks. But they don’t begin to have enough money to make a down payment on the Stretzel place.”

Of the Takemotos, only the six-year-old son had acquired any mastery of English, and now he stepped forward as the interpreter. Jabbering in Japanese, he explained to his father that the banker could not lend the missing funds, then listened as his father spoke with terrible intensity.

Turning to the banker, the boy said, “He not want money you. He want money him,” and the child pointed directly at Brumbaugh.

“Me?” This was too much. The family was deserting him, and they wanted him to finance their flight. “No!” he roared. “You leave me alone … helpless. Then you want me to pay …”

When the child interpreted this, it had a profound effect on Mr. Takemoto. Ignoring the banker, he turned to face Brumbaugh and his eyes misted. He spoke directly to Potato in Japanese, as if he knew the Russian would understand, and he made walking gestures with his fingers, and after a while the child broke in and said, “We not leave you,” and he made the same walking gestures across the banker’s desk, saying, “We walk thin beets you. We walk thin beets us.”

Brumbaugh understood. This incredible family was proposing that for the next year they would work two farms—Brumbaugh’s during the good hours, their own during the dark—and to accomplish this they were prepared to trudge twice a day the miles between.

This was in the fall of 1905, when the Russo-Japanese bitterness had not yet subsided, but in Centennial the two men looked carefully at each other, an aging Russian who had known great success in this land, a bulldog little Japanese who longed for a chance to equal it, and each knew he could trust the other. If Takemoto said he would tend Brumbaugh’s beets, he would, and after a while the Russian said to the banker, “Call Merv Wendell in here,” and in a few minutes the prosperous real estate broker joined them.

“Merv,” Brumbaugh said, “two months ago you quoted me a price of four thousand dollars on the Stretzel farm. I offered you three-five, and you said you thought they’d take three-seven. Well, Mr. Takemoto here is offering you three-seven as of this minute, and, Merv, I don’t want him to suffer any fancy business at your hands.”

“Potato!” the real estate man cried in honest dismay. “Do you think for one minute …”

“I know what you tried with Otto Emig,” Brumbaugh cut in sharply. “No fancy charges this time. Three-seven.”

“Of course, of course!” Wendell agreed. “And you’re getting one of the best farms in the area,” he said unctuously to Takemoto.

“He don’t understand English,” Brumbaugh growled. “But I do. And you see he gets it, fee simple, by tomorrow night.”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Brumbaugh, yes, sir. And when you want to sell your place …”

“That’ll be many years, Merv.”

“We aren’t getting any younger, are we?”

“I am,” Brumbaugh said, and before he left the bank he signed Takemoto’s note for three thousand dollars. Looking down at the six-year-old child who had negotiated the deal in a language he had first heard only eight months ago, he thought, I’ve never felt safer about signing a note. If the old man can’t pay, the boy will.

Next morning he visited Kurt at the sugar factory and told him, “I want you to issue Goro Takemoto a contract for twenty-five acres of beets, and I want you to see that he gets some good seed.”

The sugar industry was an ingenious interlocking arrangement whereby many disparate elements were forced to depend upon one another in creating a sophisticated whole. The factory could not exist without assurance that farmers would supply it with beets, and the farmers had no alternative but to sell their beets to the factory; there simply was no other market.

The interdependence went further. Land produced the beets, but the tops were plowed back to enrich that land. Extracting sugar produced the by-products of pulp and molasses, which could be fed to cattle, whose manure came back to keep the land productive.

Because of this interdependence, the industry found it logical to operate on a system of binding contracts, and each January the farmers waited anxiously for a visit from the company field man to sign that precious slip of paper which guaranteed that all beets raised on the allotted acreage would be purchased as from October 1, with the first payment coming on November 15.

With this contract the farmer could go to the Centennial Bank and borrow the money he needed for seeds in March, planters in April, thinners in May and his general expenses through October. Come November 15 his first check would arrive: twenty-five acres of beets, sixteen tons to the acre, six dollars a ton equals $2400.

The check was never made payable to the farmer. Invariably it read something like this: “Centennial Bank, Mervin Wendell, Otto Emig,” a shrewd precaution which ensured that the bank would recover its loan, Mervin Wendell would collect on his mortgage, and Otto Emig would receive whatever was left over.

The system was a tribute to intelligence: procedures were spelled out clearly, financed with adequate capital, and administered justly. But what Potato Brumbaugh, with his philosophical inclination, relished was the higher intricacy of beet production, for to him this proved the limitless capacity of man. One night when the Russian farmers were bemoaning the growing number of Japanese in business for themselves, he grew impatient: “Keep your eye on the beet. A hundred years ago it was a little round red thing that weighed three ounces. It was an annual, which meant that each year it produced the whole cycle: leaves, root, stalks, seeds, and it gave damned little sugar … less than one percent. Well, some smart Germans took that red thing and changed it to white. They multiplied the size until it weighed over a pound. They turned it into a two-year plant, big root this year. If replanted, seeds next year, which meant that all the first-year energy could go to making sugar. This increased the sugar content from less than one percent to fifteen percent and maybe pretty soon sixteen or seventeen. If men can do that to the beet, they’re smart enough to find us workmen to help grow it.”

It was a pretty speech, and it told the Russians things they hadn’t known before, but as Otto Emig whispered to Emil Wenzlaff, “You notice he didn’t say where we’ll find men for stoop-work when our Japanese leave.”

Everything was under scientific control except the one element which determined success or failure: where could the farmer find a labor force willing to do stoop-work without wanting to buy farms or educate children to the point where they no longer wished to thin beets? The whole intricate structure, so vital to the west, threatened to collapse around this insoluble problem.

And then one day Potato Brumbaugh rode up to Venneford to sell his crop of hay, and he warned Jim Lloyd, “After this year there may not be any hay for your Herefords.”

“Where you gonna sell it?”

“I may have to quit growing it.”

This improbable statement confused Lloyd, because he knew that a beet farmer had to grow hay; beets were so voracious in sucking minerals from the soil that no field could grow them continuously. If this was tried, the minerals would be used up, allowing sugar-beet nematodes and other insects to infest the field, stunting the beets or even killing them off. So when a provident farmer dug his beets in October, next year he planted that field in barley, then alfalfa for two years and then potatoes. Only in the fifth year would he dare to plant beets again.

This meant that a man would divide his farm into enough segments to practice this rotation, and the maximum land he could apply to beets in any one year would be one of those segments. The others had better be growing hay, or something like potatoes or barley. So if Brumbaugh intended to go on with beets, Jim knew he had to grow hay too, and he told Potato so.

“I mean I’m going to quit farming altogether,” Brumbaugh said. “I can’t find anyone to stay on the job, and neither can Emig or Wenzlaff.” He recounted for Jim his disillusioning experiences: “My Germans thinned beets two years, then bought their own farm. My Russians stayed eighteen months, and poooof! They had their own place. And those Japanese! they bought a farm in eight months. What we’ve got to find is someone who loves farming but hates farms.”

As Brumbaugh spoke these words, Jim was leaning on a gate to a field dotted with Crown Vee cows and their sleek, gentle calves. Even after all these years Jim was fascinated by the Hereford, constantly seeking to improve his herd, always trying to deduce why certain of these cows dropped strong calves.

“This bunch of calves from the same bull?” Brumbaugh asked.

Jim nodded. “That calf by the fence …” He never completed his sentence, because as he stared at the calf he remembered a day almost forty years before when he had known another calf—on the burning alkali flats east of the Pecos when he and R. J. Poteet were herding longhorns. A calf had been born and R. J. had ridden back to the drags and ordered them to kill it. Jim had been unable to do so. “I raise calves,” he had told Poteet, “I don’t kill ’em.”

And with the connivance of the chuck-wagon cook—what was his name, Mexican of some kind—he had saved the calf and later the cook had traded it to Mexican squatters farming land near the great Chisum ranch, and he could still see the joy shining in the eyes of those peons when they got their hands on that calf—the round, dark faces, the heavy black hair, the white teeth, the brown hands offering chili beans and chickens.

“I’ve got it!” he said. “Mexicans!”

South of the Rio Grande, known in Mexico as the Río Bravo, lay the huge state of Chihuahua, with its capital of the same name situated near the middle. One hundred and twenty-five miles west of the city rose the steep, dark mountains of the Sierra Madre, rich in gold and silver.

Dropping out of the mountains like a slim thread of spun silver came the Falls of Temchic, graceful and lovely in themselves but made more so by the valley into which they fell. The Vale of Temchic ran eastward from the mountains, a delicate enclave surrounded on three sides by rocky forms so unusual they seemed to have been placed in position by an artist. North of the Río Temchic stood the four guardian peaks: La Águila, El Halcón, El León, El Oso—Eagle, Falcon, Lion, Bear. Along the south side rose great masses of granite, looking like ships or sulking prehistoric animals.

For some three thousand years this valley had been the home of the Temchic Indians, a tribe of the Tarahumare, those slim, deerlike people who occupied the mountains, living with a minimal culture, so primitive were they. Old accounts claimed that the Temchics had been a handsome, gentle tribe, but this cannot be confirmed. Unfortunately, the valley they had chosen for their home contained one of the world’s major silver mines, and although they never discovered how to mine the ore, Spaniards exploring the region in 1609 did, and the Temchics were promptly rounded up, forcibly converted to Christianity and pressed into an underground slavery so terrible that by the year 1667 not a single Temchic existed, either above ground or below.

Legend said that the silver of the waterfall fell an equal distance into the earth, where it crystallized into a rich vein penetrating deep. Certainly the Temchic mines reached far down, and to bring the ore to the surface was always a problem. Long, slim tree trunks were let down into the bowels, and bare cross beams about three feet wide were nailed to the trunks, forming a suicidal ladder without railing or protection and rising almost vertically.

Up these dreadful ladders the Temchics had been forced to climb, lugging enormous baskets of ore. Year after year they lived underground, and their death knell sounded in vanishing screams as they plunged one after the other, weak and unsteady, from the tall ladders. “The last Temchic died yesterday,” the report of 1667 related, “but we have the consolation of knowing that they all died Christians.”

The vale was lovingly referred to as Temchic plateada—Silvery Temchic—and when the original Indians were gone, the Spanish operators of the mines corralled the gentle Tarahumare from the Sierra Madre, but they perished at an appalling rate, so that it was scarcely economical to continue using them. One Spanish engineer reported to Madrid: “They take one look at the deep pit and the ladders and fall to their death. I do not believe they fall through vertigo. I believe they throw themselves into the pit rather than work in darkness when they have been accustomed to the mountain peaks.”

Their place in the valley was taken by that strange and often beautiful race of mestizos—part Indian, part Spaniard—which would come to be known as Mexican. By no means could they be called Spaniards, for that blood had been seriously diluted, but on the other hand, they were not Indians, either, for a semi-European culture had displaced the Indian language, the Indian religion and the Indian way of doing things.

They were Mexicans, a new breed and a stalwart one. They were people capable of enormous effort when they saw it was needed, capable of either a compelling gentleness when generously treated or savage retribution when outraged. Many bloodlines converged in them: in Mexico’s colonial period the land contained about 15,000,000 Indians; among them came 300,000 Spaniards and 250,000 blacks from Africa, and out of this mix arose the Mexican. Since the Spaniards were dominant, and since only they had the guns and books and churches, the culture quickly became predominantly Spanish: language, military organization, religion, ways of doing business were all Spanish, so it was understandable that the new people should boast, “Somos españoles,” but they were not. They were Mexicans, and often the Spanish blood was a mere trickle.

On the other hand, since the Spaniards killed off a large percentage of the Indians and since they subjugated the blacks unmercifully, in large parts of Mexico a Spanish culture did prevail, and it was not preposterous for people there to claim somos españoles. But it was more accurate to speak of the entire population as mestizo. Certainly, in the Vale of Temchic in the year 1903 the thin, underpaid workers were considerably more Indian than Spanish.

They worked like mules. Some of the miners would be underground for days at a time. They ate little, for they were paid little. They were lashed and beaten as few workers in the world were in this relatively humane period, and when in desperation they went to the authorities for relief, they were repulsed by rural police, who took positive delight in shooting them, and by the parish priest, Father Grávez, who explained that it was God’s will that they should work in the mines and that if they agitated for higher wages, they would displease both God and Don Luis. The latter was the more important.

General Luis Terrazas owned Chihuahua, not only the city, but the entire state. Starting in 1860, he had led a minor military assault against an undefended building, and as a consequence, had ordained himself colonel. With four thousand dollars he bought himself a ranch comprising seven million acres on which he ran cattle ultimately worth twenty-five million dollars. With this as his leverage, by the year 1900 he owned three banks, four textile mills, numerous flour mills and sixteen other critical businesses with a cash value of more than twenty-seven million dollars. He also owned the Temchic silver mine, and his managers would be very angry if the miners interrupted production, thus causing him to lose income. The managers, therefore, instructed the rural police to gun down any troublemakers, and warned Father Grávez that Don Luis expected the priest to keep the valley peaceful.

It was by nature peaceful. On each side of the tumbling Río Temchic, small huts, not much larger than doghouses, lined the stream. Up the slopes, set well back from the mule trails, stood the commodious white houses of the German and American engineers who operated the mines for General Terrazas. As a result of some historical accident, all the American families came from one small region in Minnesota, and they were treated so generously by Terrazas that they came to think of themselves as his chosen agents and fell into the habit of brutalizing the Mexican workmen almost as severely as did the rural police.

“They’re really nothing but animals,” the American engineers were fond of saying as they supervised a work schedule of fourteen hours a day, seven days a week. “When they do get off work, all they do is run to their huts and womanize. They don’t need extra time.”

In some respects the American wives were worse than their husbands, monopolizing the time of the miners’ wives, using them as servants and paying them seventy-five cents a week for working ten hours a day, seven days a week. “It takes four of them a whole day to do what one white woman would do in fifteen minutes,” the wives told each other in justification, “and if you don’t watch them, they’ll eat you blind.”

Even so, Temchic was a place that people loved. It was an enclave protected from snow in winter and from extreme heat in summer. It could have been an ideal setting for the establishment of a mestizo paradise, except that silver lay hidden, and the engineers wanted it. Things would have continued to go well, thanks to the surveillance of the rural police and the church, if it had not been for a lean, long-legged, mean-visaged troublemaker whom the miners followed, but whom the engineers named contemptuously Capitan Frijoles, Captain Baked Beans, the Windy One. “I wish the rurales would gun him down,” the principal engineer said when he heard that Frijoles was talking again of a strike. “What the hell does the man want?”

What Frijoles wanted was one day off a week, no more than twelve hours’ work in the mines each day, more food, and a doctor for women who were having babies.

Captain Mendoza of the rurales visited Frijoles and warned him, “Such talk is revolutionary. If I hear you make such claims—ever again—you’ll be taken care of.”

Father Grávez also visited Frijoles and explained to him that “God gives each of us our work to do, Capitan, and your work is to bring silver out of the earth. God watches what you do. He knows your excellence and one day He will reward you. Also, General Terrazas needs the silver for the good works he does in Chihuahua.”

This line of reasoning impressed Frijoles at the moment, but later when he tried to recall one good thing General Terrazas had ever done for the people of Chihuahua, he could think of nothing. The general spent his money on big houses and bigger ranches and automobiles for his many children and trips to Europe and the entertainment of European businessmen and the paying of bribes to politicians in Mexico City. “Perhaps,” Frijoles told his fellow workers, “when he’s finished with all that, one of these days he’ll get around to us.” The miners suspected, from past experience, that this might take a long time.

So the agitation continued, and people in power resolved to destroy this troublesome Frijoles. The rural police saw him as a growing danger, and Captain Mendoza gave the simple order, “Shoot him.” The engineers saw him as a disturbance in their good relations with General Terrazas, and they agreed, “Get rid of him.” Father Grávez, and especially his superior, the cardinal in Chihuahua, saw Frijoles as an attack upon the order of the church, and both said, “He must be disciplined.” General Terrazas saw him clearly as the opening wedge of all kinds of demands from workers who wanted to work only seventy-two hours a week, and he passed the word, “Eliminate him.” And in Mexico City, President Porfirio Díaz, an old dictator aware that tremors in the north were beginning to threaten his beloved country, saw in Frijoles, the long-legged revolutionary up north, a portentous threat to the stability of the nation. “Kill him now!” the old man advised, for he had learned to recognize an enemy when he saw one.

On a bright day in February, Captain Mendoza personally led a band of his rurales, hardened men accustomed to shoot without asking questions, into the village of Temchic, intending to arrest Frijoles. On the way back down the valley the revolutionary would be set free, and the gunmen, fourteen of them, would shoot him down, “as he was trying to escape.” This Ley de Fuga, the Law of Flight, saved both jail and court costs.

“Don’t shoot him here,” Captain Mendoza instructed his men. “It always makes the women scream, and we don’t want any agitation.”

As he entered the town he stopped at the office of the engineers and assured them, “You’ll have no more trouble with Frijoles,” and they thanked him, for engineers the world over wanted workmen to tend their jobs, work long hours and keep their mouths shut. “We’ll have him out of here in fifteen minutes,” Mendoza assured them.

It was a long fifteen minutes. Frijoles, anticipating that his enemies might strike, had prepared his cohorts for this day, and now as Mendoza and his henchmen turned the corner leading to the mine, they were met by a fusillade which killed the captain and three of his lieutenants. A pitched battle ensued, and when the rurales ran back down the valley, they left seven of their men dead on the banks of the Temchic.

A convulsion swept Mexico. This was revolution, the defiance of established authority, and all responsible people in the nation recognized the danger. An army battalion from Chihuahua was dispatched to Temchic, but was ignominiously defeated by Frijoles and his resolute miners. A new army was convened at Durango, with reinforcements moving in from Torreón, and this, too, was defeated. Generals long accustomed to terrifying farmers on open land discovered that they could not throw unlimited forces against Temchic, because they couldn’t be crowded into the narrow defile. This time it was seventy soldiers against seventy miners, and the latter were fighting for their homes and a new way of life.

The war strung out from February till October, with the miners organizing their village as a redoubt capable of withstanding almost any assault. The American engineers and their families were sent down the valley under armed escort, and were now in Chihuahua city, giving interviews which explained that Frijoles and his gang were insane demons bent on destroying Mexico. The Germans were gone too, all except one quixotic young man who elected to stay with Frijoles and the miners. “We’ll take care of him when this is over,” the other Germans said, and they assured General Terrazas that it would soon end, because, as they explained, “Frijoles isn’t even educated.”

Then, in late October, a very brave young captain named Salcedo grew impatient with the pusillanimous behavior of the fat generals and devised a daring plan for climbing the Sierra Madre and sweeping down from the west while the generals moved up the valley and in from the flanks. The plan worked, and by the end of October the revolution at Temchic was doomed.

At this point the men around Frijoles made a desperate decision. He must escape—somehow he must get out of the valley to lead the revolution in other parts of the country. They had no doubt that the evil old order whereby one man could own seven million acres of land and dispose of it as he wished would vanish. They would be dead, but in that new day men and women would not work fourteen hours a day, seven days a week. So they devised a plan whereby four of them would set up a diversion to distract Captain Salcedo. They could not hope to escape; surely they would be shot—but their deaths would provide Frijoles with a chance to scurry into the mountains and on to the real revolution which lay ahead.

The strategy succeeded, and by dawn Frijoles was far into the mountains. When he stopped to rest on a log beside the river, he could hear in the distance the cannonade of government troops overrunning his village. When he chanced to look up he saw a file of nearly naked Tarahumare Indians passing, thin, swift runners from the highest mountains, and his eyes filled with tears of rage. For a moment he looked at them as they ran, silent men confused by the appearance of a stranger in their land, and he wondered why over the past generations the miners and the Indians had not somehow united in a common struggle for justice, and then the shadowy Tarahumare were gone, and he realized that never in the history of Mexico could such a union have occurred, for the Indians were Indians and the miners were Mexicans, and there was no chance of mutual understanding.

When Temchic was subdued—with German and American engineers reinstalled in their big houses—a matter of discipline arose. Nineteen of the rebellious miners had been captured alive, along with three women who had supported them, and it was decreed in Mexico City that they should be publicly shot as a warning to other potential troublemakers. Then someone had the creditable idea that it would be better if the doomed men and women were executed not by soldiers or rurales, who did a good deal of that sort of thing, but by ordinary villagers from the region, as if to show the world that sensible Mexicans shared no part of the miners’ revolution and did indeed reject it.

Captain Salcedo, who had emerged from the final assault as some kind of national hero, was therefore commissioned to move into a village of farmers three miles down the valley and conscript a firing squad. In the selecting he was to be assisted by Father Grávez, whose church stood in the village and who could identify the men best suited for such service.

Like Temchic, Santa Ynez clung to the sides of the river, but there the resemblance stopped. Its houses were the white adobe habitations of men who worked the soil, and not the dark hovels of miners. Nor could it boast commodious houses on the hill, for no Germans or Americans would want to bother with its meager riches. It did, however, contain one spot of excellence that surpassed anything the mining town could provide, the Spanish colonial church of Santa Ynez with its two historic doors.

They were massive and made from wood which Tarahumare Indians had lugged down from the Sierra Madre. They had been carved by some forgotten priest who had learned his art in Taxco to the south, and depicted two scenes from the life of Saint Agnes, as she was known in Europe, the saint whose holy day came on January 21, when nights were bitter chill, as the poet Keats had said in his poem.

The left door showed Ynez, the radiant child of thirteen, holding in her right hand a sword, the instrument by which she was martyred, and at her feet a protecting lamb which signified the purity of her life. The right door showed her entering into her heavenly marriage with Jesus. But it was the combination of these two doors, each complementing the other, that epitomized the town’s youthful innocence. It was a clean town, perched high in the Sierra Madre and protected on three sides by the pinnacles of those mountains.

It was a village to be loved, especially on the saint’s day, when the population convened in darkness to sing before the doors of the church. All waited in silence, watching eastward for the first rays of the sun. When it appeared, farmers’ voices joined with those of their wives and children in the traditional birthday song, “Las Mañanitas,” honoring the little girl they loved:

“This is the birthday song

Sung by King David.

Because this is your day,

I sing it to you.

If the night-watch at the corner

Wants to do me a favor,

Let him dim his lantern

While I whisper my love.”

“We need one reliable man to act as sergeant,” Captain Salcedo explained as he marched into the village with the priest. He was a trim man, with a small mustache and highly polished brown German boots which made a formidable impression on rural people.

“Tranquilino Marquez,” the priest said without hesitation. “Solid man, twenty-three years old, married to a good woman named Serafina, with two children.”

“He won’t give us trouble?” Salcedo asked. “No speeches or anything like that?”

“Tranquilino?” Father Grávez asked. “Utterly reliable. Works his small plot. Pays his rent to General Terrazas like a good citizen.”

Captain Salcedo summoned Tranquilino, and when the young farmer stood before him, taller than average, thin-faced, barefoot, straw hat deferentially in hand, the officer knew intuitively that here was the stolid, obedient type that made Mexico strong. “You’re a fine-looking man. You’re to stand at the right end,” he said enthusiastically. “Sort of a sergeant. I’ll give the command but you’ll see that your men are in line.”

“To do what?” Tranquilino asked.

“Oh! We’re executing the rebels. You’ve fired a gun, of course?”

“Yes. But I don’t want to shoot …”

“It’s your duty! You don’t want rebels destroying your farm … your family?”

“I sell corn to those miners.”

“Tranquilino! Mexico must rid itself of these criminal men. Explain it to him, Father.”

So Father Grávez took Tranquilino aside and explained everything in clear, simple terms: “The mines belong to a good man, Tranquilino. General Terrazas does many fine things for Mexico, and if we allow strikers to steal his silver …”

“They didn’t take silver.”

“Of course not. But when a workman strikes and doesn’t produce what he’s supposed to produce, it’s the same as stealing. He deprives General Terrazas of things that are rightfully his.”

This made sense, and what Father Grávez said next made even more sense. “It’s just as if you lived on land belonging to the general and you refused to grow corn for him. Wouldn’t that be stealing from him?” Tranquilino had to agree that it would be, and never in his life had he stolen from anyone or given the rurales cause to discipline him.

Step by step Father Grávez explained why it was necessary for the farmers of Santa Ynez to shoot the miners of Temchic, and in the end Tranquilino was convinced. Those men who had listened to Frijoles were a menace to Mexico and had to be exterminated.

But when Father Grávez took Tranquilino to headquarters, the head of the American engineers came into the room where Salcedo was choosing his firing squad and said, “We’re still short eleven men in the mines. We’d better take a dozen or so of these farmers and convert them to miners,” and Father Grávez, always subservient to the authorities, said, “There’s no better man in the region than Tranquilino here,” and the engineer turned to Tranquilino and said, “Good. You can start in the mines right after the executions.”

“It’s an opportunity,” Father Grávez explained. “You’re given your food and you don’t have to farm any more.”

Tranquilino wanted to say, “I like to farm. I don’t want to work down in a mine and never see the sun.” But he sensed that if he said this, with Captain Salcedo and the engineer and Father Grávez listening, he would be in serious trouble. Things were happening too fast, and he wanted to talk with Serafina, who understood complexities better than he, but instead he was handed a gun and marched up the valley to Temchic, where two dozen other confused farmers had assembled, and he heard Captain Salcedo saying, “Men, you are to line up on Tranquilino here. He’s your sergeant.”

And they lined up, that bright, hot October morning, and the nineteen rebels were led out, ordinary men like Tranquilino, and behind them came three women with rags tied across their lips, for women are apt to scream, and the farmers heard Captain Salcedo giving directions: “We’ll shoot them in batches of six. Now, men, when I give the word ‘Fire’ you’re to shoot at the prisoner opposite you. Right at his heart.”

On the first fusillade all the farmers fired at the prisoners standing toward the ends of the line, with the result that two men in the middle were left standing. Captain Salcedo had to leave the firing squad, march across the open space, and kill the survivors with his revolver, standing very close to them and shooting into their faces.

The second time the same thing happened, and after Salcedo had fired point-blank at the two surviving miners, he berated the farmers, telling them that they would make a sorry lot of soldiers. He explained that he would now divide the firing squad into six groups, each being responsible for the execution of one of the miners. “And this time, if one of those six men over there is left standing, I personally will shoot the lead man in the squad that was responsible.” He stalked down the line, punching his forefinger at each of the six leaders, striking Tranquilino first. There could be no doubt that Salcedo meant what he said, and this time there were no survivors.

“Good!” he congratulated the farmers. “Now bring on the last man and two of the women.”

When the trio was moved into position against the wall, Tranquilino saw with relief that his group would be responsible for the man. He could not fire at a woman, and apparently some of the other farmers felt the same way, for their bullets went high, very high, leaving pockmarks in the wall and one defiant woman standing. In her anguish her bandage had slipped loose, and she started cursing Salcedo and the engineers, and in the end Salcedo had to shoot her in the face.

Grimly he returned to the farmers. “This last one is Frijoles’ wife. She was worse than he was. If there is one bullet high on that wall, I’ll bring in soldiers and shoot the lot of you. Now get ready.”

The woman stood with her feet apart, her back pressed against the wall. She was mute, but her fiery eyes blazed curses at her executioners, reminding them of empty bellies and years lost in the mines. Before Captain Salcedo could give the order to fire, Tranquilino Marquez threw down his gun, uttering just one word, “No,” and like falling stalks of wheat the other rifles fell into the dust.

In a rage Captain Salcedo rushed across the open space and executed Frijoles’ wife. Then he stormed back and would have shot Tranquilino, but the thin-faced farmer was saved by Father Grávez, who stepped before him in intercession, saying, “He’s a good man, this one. Spare him.”

As the twenty-two corpses were hauled away, Tranquilino Marquez walked down the valley like a ghost. The echo of his rifle still sounded in his ears, the staccato fire of Captain Salcedo’s fierce revolver. He heard the woman screaming, and the saving voice of Father Grávez. But most of all he heard those terrible words which sentenced him to a life underground: “He can start in the mines right after the executions.” They would be coming for him soon and he hurried his steps.

He started running, and when he reached his adobe at the far end of Santa Ynez, he burst into the room, threw his arms about his young wife and cried, “They’re coming after me.” Serafina Marquez had watched the executions from the crest of a small hill and had seen her husband throw down his rifle, and then after Father Grávez saved his life, she had seen Captain Salcedo talking agitatedly with the new captain of rurales, and it was clear to her that the captain was ordering the policemen to arrest Tranquilino as a troublemaker and shoot him as he tried to escape. She had already decided what must be done.

“You must go north, Tranquilino.”

“Where?”

“Go over the fields and catch the train at Guerrero. This instant!”

“Go where?”

“Cross the Río Bravo. There’s always work across the river.”

“The children?”

“We’ll stay here. We’ll do.”

“But—Serafina!”

“Go!” she screamed. And in three minutes she had packed him a parcel of food and given him all the money they had saved. “You can send us some when you find work. The way Hernandez does with his wife.” And she shoved him out the door.

It was not a minute too soon, for down the Vale of Temchic came the rurales, asking directions to the home of Tranquilino Marquez, troublemaker.

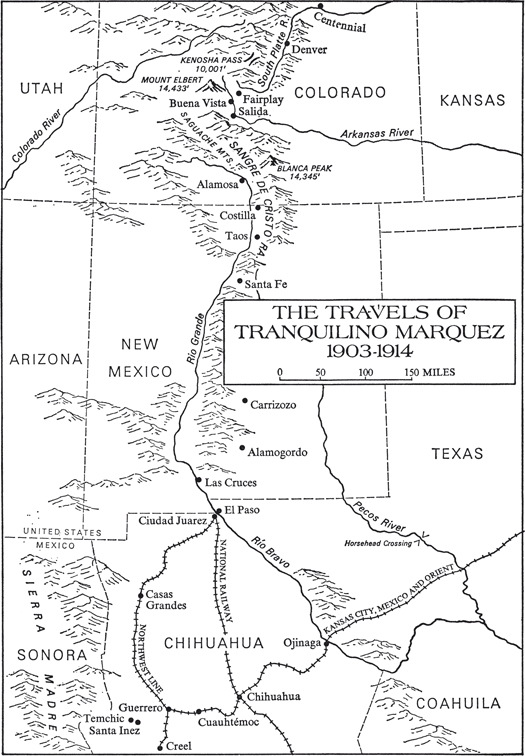

One of the notable features of northern Mexico was the network of plodding railroads which crisscrossed the area. In Chihuahua one improbable line called the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient entered from southern Texas to peter out at a railhead hundreds of miles short of its announced destination at the Pacific Ocean.

The main line ran north from Chihuahua to the border city of Ciudad Juarez, where a bridge carried it into El Paso. A third line was the most interesting, and the one destined to be a focus of history in this period. It, too, ran from Chihuahua to Ciudad Juarez, but along a route well to the west, through such picturesque towns as Cuauhtémoc, Guerrero and Casas Grandes, which had been an important center a thousand years ago, with ancient pyramids and ruined streets still proving how great the pre-Columbian Indians had been.

It was for this Northwest Line that Tranquilino Marquez headed, traveling mostly at night. He came at last to the vicinity of Guerrero, where he hid for two days, finally slipping into town at dusk to buy much-needed food. That night he traveled north to where the railroad stopped to take on wood for its furnaces and water for its boilers, and there, where no guards watched, he climbed beneath one of the freight cars and fastened himself to the iron rods that ran the length of the car. In this precarious way he rode to Casas Grandes, where some farmers headed for the United States detected him.

“Come on!” they whispered, kneeling to see how he had kept himself from the wheels.

“We ride inside!” one of the men said in a low voice, and they dragged him out and showed him how to force open doors on the freight train.

“At Ciudad Juarez we climb down before the police catch us, and an hour later we’re across the border.”

In those days no papers were required to move from Mexico into Texas, but as the men prepared to cross the river the leader warned them, “If they ask you, say we’re on our way to Arizona.” Tranquilino asked why, and the man said, “In Texas they hate Mexicans, and if they think we’re staying there … trouble. So we always say Arizona. In Arizona they don’t give a damn what happens.”

At the northern end of the bridge a jaded customs official asked the men, “You bringin’ any guns?” They were obviously bringing nothing but their clothes, so he let them through, for at that time the United States needed field workers.

Some of the immigrants headed northeast to the prosperous parts of Texas, and a few went directly west to Arizona, en route to California, but one who had been north before took Tranquilino aside and whispered, “The good jobs are in New Mexico. You stay with me.”

There followed one of the quietest periods of Tranquilino’s life. From October 1903 till March 1904 he wandered north through the majestic state of New Mexico, seeing roads and valleys of a beauty he could not have imagined, with fields leading gently up the sides of mountains until snow-covered crests were reached. Always he was in the companionship of men who spoke Spanish, and although the only jobs he could find were menial, they did pay cash, and he learned the sweet secret of Mexicans who worked in the United States:

“In any town, Tranquilino, you can go to the post office and tell the man ‘Giro postal,’ and you give him your money and he gives you a piece of paper which you send to your wife. He’ll write her name on the envelope and she’ll get the money.”

For six months he went from one post office to the next, asking for the giro postal, and without once knowing whether she received the money or not, he sent Serafina and the children every penny he earned, taking out only what he needed for the most meager necessities. Las Cruces, Alamogordo, Carrizozo of the beautiful hills, Encino, Santa Fe, Taos, Costilla—in each town the postmasters sold him the “giros” and addressed his letters, as they did for hundreds of other workers.

New Mexico was so elegant a state, and so congenial to Mexicans, that he thought of living there permanently—bringing his wife and children north to build a home somewhere in the Santa Fe area if he could get a job on one of the ranches, but in March 1904 this dream was postponed when a man came to the area around Costilla, asking, “Any Mexicans here want a real fine job growing vegetables at Alamosa … up in Colorado?” And he offered such phenomenal wages—four dollars a week besides food and lodging—that Tranquilino and several others jumped at the chance.

They were taken by wagon north to where Blanca Peak guarded the road, then west to the irrigated lands around Alamosa, where Tranquilino saw that magnificent valley reaching off to the north, with the Sangre de Cristo mountains to the east and the Saguache peaks to the west. He felt privileged to work in Alamosa, where numerous storekeepers spoke Spanish, and he began to think that Colorado was an even better place than New Mexico, until he became aware that many citizens of the small city cursed Mexicans, and accused them of all sorts of evil.

Certain Americans in western states, having lost their Indians and with few blacks at hand, naturally turned to hating Mexicans, and they devised many tricks to torment the dark-skinned strangers. The sheriff in Alamosa arrested Mexicans for even the most trivial offenses, and judges sentenced them harshly and without the semblance of a trial. Storekeepers charged them higher prices than they charged white customers, and there were many places like barbershops and restaurants into which a Mexican could not go. Their money was welcome, but they were not.

But even after three ugly brushes with the law over charges he could not understand, Tranquilino, a quiet man seeking to avoid trouble, told his Mexican jailmates, “It could be worse. If I wasn’t here, I’d be down in the silver mines at Temchic, or more likely dead.” And he gained a reputation in Alamosa as a reliable man. He was the first at work, the last to leave, and he never lost his good humor.

“Hello, Mr. Adams! Yes, Mr. Adams! Right away, Mr. Adams.” He did not behave in this manner because he was subservient. He did so because he was glad to have a job, because he was grateful for the raise to five dollars a week, which enabled him to send even more money to his wife in Santa Ynez.

Some of his fiery companions chided him with being afraid to stand up for his rights, but he told them, “I have all the rights I need. I stay away from the sheriff and I haven’t been in jail for eight months.”

He was now in his third year of sending money back to Mexico, and he still had not learned whether his wife was getting it or not, so in October, when the crops were in, he told Mr. Adams, “I’m going down to Chihuahua,” and Mr. Adams, not unhappy to have one less hand to worry about through the workless winter, told him, “A fine idea, Tranquilino, and next spring your job will be waiting.”

There was a train to El Paso, and for a small fare he was able to ride to the border. There he walked over the bridge and was greeted amiably by the Mexican officials. “Santa Ynez,” he told them, and a lieutenant said in reply, “Watch yourself, my friend, and stay clear of the revolutionaries who are pestering that region.”

“I just want to see my wife,” Tranquilino said. “I haven’t heard from her in three years.” He went out to the yards of the Northwest Line, where scores of other men coming home from the United States were waiting to catch a boxcar heading south.

On the way to Guerrero, Tranquilino learned for the first time of the serious troubles erupting throughout Mexico, and he heard firsthand reports of how Colonel Salcedo, the hero of Temchic, was dominating the area, a cruel man in leather puttees who shot field workers if they uttered a word against General Tarrazas or President Díaz.

But he also heard romantic tales of Capitan Frijoles, who was hiding somewhere in the Sierra Madre, tormenting the government troops with audacious sorties, and he felt a sense of elation to think that the rebel, whom he had never seen, was still alive.

Then, when the train was well south of Casas Grandes, Tranquilino had his first experience with real revolution. Someone had mined the tracks of the Northwest Line, and although the engine passed over the dynamite safely, along with the car that carried the wood for the furnace, the following cars were ripped apart, killing the men riding within, leaving Tranquilino’s car edging the fiery spot.

Survivors climbed down to survey the wreckage, and soldiers moved in from a headquarters to the south. Everyone was placed under arrest, and later in the day Colonel Salcedo, now in full control of his district, stormed onto the scene and began questioning suspects. Man after man told the same story: “I am coming home from work in Texas, Mi Coronel,” and it was obvious that they were telling the truth.

Salcedo grabbed Tranquilino roughly, stared at him without recognizing him and snapped, “You? What’s your story?”

“I’m coming home from Colorado.”

“Where’s that?”

“North of Texas.”

“Where are you going?”

Tranquilino was on the verge of saying “Santa Ynez,” but he judged correctly that this might arouse suspicions or even a recollection of the insurrection which had occurred there. “I’m getting off at Guerrero,” he said, and Salcedo passed on.

The colonel’s men, however, identified three revolutionaries, who were lined up against a wall and shot. “Let that be a lesson to you men coming back to Mexico.” And after a while the track was mended and the train resumed its way to Guerrero, where Tranquilino left it, heading overland on foot for the beautiful Vale of Temchic.

As he passed the four guardian peaks and entered the southern end of Santa Ynez, children began to yell, “Tranquilino Marquez is coming home!” And a crowd surrounded him and boys yelled, “Victoriano! It’s your father!” And a shy, small child whom Tranquilino did not recognize stepped forward, wearing good clothes that his father had paid for with the giros postales, and the two stared at each other like strangers.

It was a prolonged, gentle visit. The children looked healthy; Serafina had spent her money wisely. In a box she had each of the envelopes from the strange towns: Alamogordo, Carrizozo, Taos, Alamosa. A neighbor who could read had deciphered the names for her, and she had said, “They sound like towns in Mexico.”

Father Grávez was pleased to see Tranquilino and told him, “You are a man of some nobility—alguna nobleza—because for three years you have never once failed to send money to your family. There are others …”

Tranquilino discovered that he enjoyed talking with the padre. “Is it true,” Grávez asked, “that in Estados Unidos you work only six days a week and have part of Saturday off?” When Tranquilino explained the working conditions and the availability of medical services for everyone … “You have to walk four miles to the doctor and if you have the money, you must pay,” he explained, “but when Guttierez lost a leg, nobody charged him anything and an Anglo woman in Alamosa gave him crutches.”

“It should be that way,” Father Grávez said.

Tranquilino asked the priest whether it would be a good idea to take Serafina and the children to Colorado, and Grávez said, “No, women and children should stay close to their church,” and Tranquilino argued, “They don’t blow up trains in Colorado,” and Father Grávez admitted with some sadness, “Perhaps the time may come when you will have to take your family north. But not yet.”

As the weeks passed, with only vague echoes of the trouble in the north, Tranquilino discovered anew what a jewel he had in Serafina Gómez. She had a disposition like the clotted milk he ate in Alamosa, gentle, lambent, always the same. In her youth she had worked in the fields like a burro, and now, even though Tranquilino supported her well, she continued to work as hard, but for different and larger purposes. She tended the sick and cared for children whose fathers were killed in the mines. She helped at the church and was called upon by Father Grávez in any emergency. Mexico had millions like her, if it ever discovered a way to release their energies, but for the present, they slaved in mining towns like Temchic or tended gardens in small villages like Santa Ynez.

She was embarrassed when she told Tranquilino that she was pregnant. “You won’t be here to see the baby,” she said, and in the intimate conversation which followed she whispered a secret to her husband: “When you were gone and no money had arrived and we were near to starvation, for everyone was afraid to befriend us, a man crept to the door at night bringing us food and a few pesos. Who do you think it was?”

Tranquilino named three of his friends, but it had not been they. “It was Frijoles,” she said. “He came to bless you for refusing to shoot his wife. I hid him for three days.” Nothing more was said, but now the revolution seemed very close to the Marquez family.

It was an easy trip back. He crossed the border in the last week of 1905, worked in Carrizozo a few days, then drifted up to Taos, then on to Alamosa, but when he reached there, he found that Mr. Adams had already hired a full complement, so he wandered north to Salida, where he tried to find work on a lettuce farm, but they didn’t need anyone, so he went over the mountains to Buena Vista, where he lodged with a Mexican family and worked on the road for a couple of weeks. After this he went on to the high town of Fairplay, where he tried to find odd jobs.

There he met a fellow Mexican who was living in Denver—Dember, the man called it—“best city in the world,” and in the wake of this man’s enthusiasm he continued his way east across the great mountains and came at last to that final ridge from which the traveler could look down on the city of the high plains.

Denver! What a mecca for the Mexican worker! Here, in the winter months when work in the fields had ended, men gathered from all parts of Colorado, and when the snow fell deep in the streets and avenues, the Mexicans huddled together with good songs and beer and dances and toasted tortillas and talk of home.

Denver! It was a city perched a mile high, loved by ranchers who brought their cattle to the winter show, loved by lonely men out on the drylands who came in for a good steak dinner, but loved especially by the Mexicans, who could lose themselves in the small streets where Spanish was spoken.

“This is ten times better than Chihuahua city,” Tranquilino told the men he was drinking with.

“You ever been to Chihuahua?” one asked.

“No. But this is better.”

He spent two months in Denver, earning money at eight different jobs. But life in the golden city was expensive, and he found himself with little left over to send south. Then one night in a cantina where there was much singing, he met Magdalena, a young woman of twenty-two who could have had any man she wanted, and she invited him to live with her. She had a job in a restaurant and together they could eat well.

“Why me?” he asked in real perplexity.

“Because you’re good-looking … and kind,” she said. “I’m tired of fighters. You’re like your name. It would feel good to come home to a man like you.”

She was altogether different from Serafina, whom he never mentioned. Magdalena had a turbulence of spirit, a wildness in her love-making. She liked to be with men, but she was afraid of them and was at ease only with Tranquilino. When it came time to pay the rent for their room, she discovered that he had been sending giros postales to his wife in Old Mexico, and instead of becoming angry, she kissed him feverishly, crying, “That’s why I need you, Tranquilino. Because if I was your wife and you were away, you’d send me money, too.”