BY THE YEAR 1911 NORTHERN COLORADO HAD EVOLVED A SYSTEM of land use which had to be judged one of the most advantageous in the world. Had it been allowed to develop unimpeded from that time on, it would have converted this part of America into a preserve of beauty, ensuring a neat balance between the needs of man and the dictates of nature.

How appropriate it was. The vast plains were reserved for cattle, sixty or seventy acres to a cow-and-calf unit. It was true that barbed wire tended to enclose each man’s land, but since ranches ran to seventy and eighty thousand acres, an owner could ride many miles across his property without encountering a road, a house or a town. The range was shared by deer and antelope, but anchored the soil so that even the stiffest wind did little damage. Only thirteen inches of rain could be expected each year, barely enough to keep things going, and if a rancher allowed his stock to overgraze an area, it could take five or six years for the grass to recover.

Cowboys prospered on the plains and created their own culture. For example, Texas Red, one of the heroes of the 1887 blizzard, became so proficient with his lariat that the Crown Vee ranch issued challenges to the cowhands on neighboring spreads, and rustic competitions were held, often supplying contestants for the famous Cheyenne Frontier Days and those other rodeos which flourished throughout the west.

“Crown Vee also produced Lightning, the notorious bucking horse that succeeded in keeping riders off his back for nine years. Texas Red, the man who came closest to staying aboard for the regulation ten seconds, said of this cantankerous beast, “Never was a horse that could sunfish the way he did. Straight in the air, then roll over with his belly up, then down with all four legs thrashing and his backbone in a knot.”

The best thing about the ranches, however, was the careful superintendence they gave the range. “All in this world we got to sell,” Jim Lloyd often instructed his men, “is grass. The Hereford, handsome though he may be, is just a machine for converting grass into beef. If you look out for the grass, I’ll look out for the Herefords.”

There was a built-in conservatism in the rancher. He wanted things left as they were, with him owning his eighty thousand acres and with the government intruding as little as possible. All he wanted from Washington was free use of public lands, high tariff on any meat coming in from Australia or Argentina, the building and maintenance of public roads, the control of predators, the provision of free education, a good mail service with free delivery to the ranch gate, and a strong sheriff’s department to arrest anyone who might think of intruding on the land. “I want no interference from government,” the rancher proclaimed, and he meant it. In return, he would look after his grass, share some of it with the wild animals and protect one of the greatest natural resources of the nation—the open range.

The rancher’s partner, although any rancher would have been offended if someone had suggested that a Russian or a Japanese was his companion, was the irrigation farmer who took the lands along the rivers and cleverly led water onto them, creating gardens out of deserts and multiplying fiftyfold the value of the land in one summer. These men used small amounts of land for which the rancher could not profitably compete, and with sugar beets they brought into the community an assured supply of cash which helped maintain the services which only towns and villages could provide.

It was a fruitful symbiosis: the rancher utilizing land which got little rain and the irrigator concentrating on those marginal lands where irrigation could be utilized. Neither trespassed upon the other and neither tried to lure away the workers employed by the other. No self-respecting cowboy would chop sugar beets, while the average beet worker was terrified by a steer.

Like the rancher, the irrigator was a conservative and despised any intervention from government. What he wanted principally from Washington was the maintenance of a very high tariff against cane sugar, Cuban especially. Had there been a free sugar market in these years, the cane growers of the Caribbean could have supplied all of America’s needs, and at a much lower price than Central Beet, using beets, could have matched. The sugar-beet industry was not really feasible, economically speaking, but it was close enough to the margin to warrant the protection given it, and the one requirement for being a senator from Colorado was to have the muscle to keep a high tariff on cane sugar. Integrity, hard work and statesmanship were desirable, but familiarity with the sugar beet was essential.

The irrigator expected a few other services: a constant supply of immigrant labor from Mexico, protection against labor unions, a very low tariff on cheap nitrates from Chile, good roads from farm to factory, low railroad rates and an ample supply of currency, but for the most part the irrigation farmer considered himself an independent man who faced the risks of agriculture alone, and the character of a society depends more upon what men think of themselves than upon what they really are.

The few towns that sprang up on the plains were geared to the needs of rancher and farmer. Banks, hardware stores, department stores and railroad stations adjusted to the cycle of the land. Each year, on November 13 and 14, the days prior to the issuance of sugar-beet checks, the community throbbed with excitement, and merchants totted up their account books to see what each farmer would owe when his check came through, and stores selling dresses redid their front windows. It was the same when one of the great ranches was shipping a trainload of cattle to Chicago; the whole railway system seemed to gird itself for that event, and men went to the station to see the stockcars loaded with steers.

This spacious way of life was possible only because the population of both the United States and Colorado was low. In 1910 the nation had 91,972,000 citizens, Colorado had 799,000, Denver had 213,000, Centennial had 1,037. A farmer could locate his beet field fifteen miles outside of Denver, and no one cared, because no one coveted his land. The Venneford Ranch was still allowed to keep hundreds of thousands of vacant acres, primarily because no one had visualized any better use for them than the running of cattle.

So for a few years around 1911, northern Colorado was as placid as it had ever been, and life in towns like Centennial was close to ideal. Then came Dr. Thomas Dole Creevey, and this agricultural stability was shattered.

Creevey was built like a duck, a round, chunky little man about five-feet-five with a large head and heavy glasses. He wore a suit which seemed too small and a vest whose two bottom buttons could not possibly fasten. He had unbelievable energy and an honesty which beamed from his animated face. Like most dedicated men, he had made one big discovery which consumed his life: he was a true believer, one who had seen the answer, and he had the power which such total dedication generates. Above all, he was a likable man whose enthusiasm infected his listeners. Men trusted Thomas Dole Creevey and were never abused in that trust. Of course, sometimes a farmer using his methods failed to duplicate his results, but even then they never charged him with fraud, because if they did, they knew that he could come onto their land and prove that what he had said was true.

He was a revolutionary, a man with a wildly disruptive idea, and when he put his plan into operation, the easy monopoly of rancherirrigator would no longer exist. It was natural, therefore, that the men who had been monopolizing the land feared him, for his announced mission was to challenge them.

In the small Iowa town of Ottumwa, Dr. Creevey was about to enter into his peroration. He was addressing an assembly of farmers who had gathered in the school auditorium to hear the new apostle of the west, and as he looked down into this collection of intelligent faces, this gathering of men who wanted to know the facts behind the rumors, he felt inspired, and whenever this happened he spoke in a lower voice than usual, allowing the force of his ideas to take the place of rhetoric:

For the past hundred years they have lied to you. They have said, “Everything west of the Hundredth Meridian is a desert.” This is not true, and I have proved it. In a few minutes we will lower the lights and I will show you what a man can grow on that desert. I will show you tall spires of corn, and huge potatoes, and fields of wheat unmatched.

It was the great Jethro Tull working in the fields of England in the years 1720–1740 who made the discovery upon which your future and mine depends, that whereas many crops can be grown with forty to sixty inches of rain a year, equally fine crops—not always of the same plants—can be grown by careful procedures where the rainfall is only twelve inches a year.

Here he explained how Jethro Tull had worked this miracle, and his words were so persuasive that the Iowa farmers began to be convinced, and Earl Grebe leaned over to Magnes Volkema and whispered, “Do you think it can be done?” They listened intently as Creevey explained how Tull’s principles could be adapted to states like Kansas and Colorado, and they experienced a flush of excitement when the doctor stopped dramatically and called to the auditorium janitor, “Bring in the stereopticon!”

The machine was set up and the lamp lit. Then, as the janitor inserted the hand-colored slides, Dr. Creevey showed the Iowa men what he had accomplished on a fourteen-inch-rainfall farm in western Kansas. It was a startling exhibition, a demonstration of how man’s ingenuity and perseverance could triumph over obstacles. There were scenes of the land before Dr. Creevey took over, and several photographs of contiguous land untouched by Creevey which remained as empty at the end of the experiment as at the beginning. Best of all were the autumn shots of the harvest he had made on this bleak soil: corn, wheat, potatoes, tomatoes and rich fields of lucerne.

The stereopticon was turned off and the lights turned up. In his final exhortation he addressed the farmers with honesty and common sense:

You saw the corn. I raised it with my own hands, but I must warn you that corn is not a good dry-land crop. If you are set in your ways and insist upon growing corn and feeding it to your hogs, do not move west. I doubt that potatoes are an appropriate crop, either. But if you want to raise wheat, for which there will always be an unlimited market of hungry humans, then the west is your destination. If you want milo for tilth, and lucerne for your neighbor’s cattle, then the free west is the place for you.

But, gentlemen, do not come west unless you want to work. Do not join me if you want to plow your field once and let it go at that. If ample rain has made you lazy, stay home. Because on those fields only the man who works from sunrise to sunset can make his fortune.

I said fortune, and I mean fortune. Every man in this room is entitled by law to 320 acres of God’s finest dry-land farm. All you have to do is go there, register your claim in the land office and go to work. I can hear you asking, “What’s in it for him?” and I’ll tell you what’s in it for me. I am employed by the railroad and by a consortium of real estate companies who own land in the west, and after you’ve taken your homestead and got your hands on some land, we will sell you additional land, the best in the area, for eight dollars an acre. What are you paying for land in Iowa? One hundred and fifty dollars an acre, and most of you can’t afford to own your own farms. Come west with me and for one-twentieth as much you’ll be twenty times wealthier.

He spoke with conviction, and when he came to his conclusion, many of his listeners leaned forward:

When I say “Come with me,” I mean it. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. With the assistance of the Rock Island Railroad, which wants to see the west developed as much as I do, I am going to invite two men from this audience to visit my demonstration farm to see for themselves what can be done. All they have to pay, and I mean all, is their meals on the train and in the hotel. And if their wives pack them a big enough lunch, they won’t even have to spend that. Now, whom do you nominate to come out with me and make the report?

Amid good-humored banter, Grebe and Volkema were selected, and were handed passes from Ottumwa, Iowa, to Goodland, Kansas. A few days later they disembarked into a forbidding wonderland. When Dr. Creevey piled them, and one hundred and twenty-nine other visitors, into the railroad’s autobuses and drove northward, they were appalled by the bleak aspects of the land: no trees, no streams, no signs of rain.

In the bus Earl Grebe sat near Dr. Creevey, and found himself confused: on the one hand, he could see the arid quality of the area to be tilled and knew from his Iowa experience that only a miracle would permit wheat to be grown here; but on the other hand, he was subjected to the wild enthusiasm of the round little agriculturist: “When I see land like this, gentlemen, my heart explodes. What a challenge! What a promise! I assure you that I can take land exactly like this and make it produce twenty-six bushels of wheat to the acre.”

“Have you ever done it?” Grebe asked.

“Done it? I’m doing it now. That’s what I’m taking you to see.”

“On land like this?”

“Not as good as this. Gentlemen, within the hour you will see my miracle. You will see the Word of God come down to earth and made real. I started dry-land farming on that sacred Sunday morning when I was staring out the church door at the bleak and empty plains of my youth. Nothing grew on those plains, and I heard the minister reading from the Book of Genesis, ‘And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.’ And the word of God descended upon me at that moment, and I understood.”

Grebe was looking at Dr. Creevey as these words were spoken, and he observed the sincerity in the man’s face. Then Creevey added, “And subdue it! That is what God wants us to do with this land, and I shall show how each of you can go forth and subdue your portion.”

When the autobuses drove into the yard of Dr. Creevey’s experimental farm, the visitors knew that they were in a special place, for the farm machinery was clean and the barns were in order. But the group did not linger there, for Dr. Creevey was eager for them to wander over his fields and see for themselves what could be accomplished with dry-land farming.

They walked several miles. Some fields were fallow, some were growing grains Grebe did not recognize, and some were about to be plowed. The pattern bore no relationship to what an Iowa farmer would be doing with his land in September, and Grebe quickly realized that if anyone were to dry-farm, he must listen to the experience of someone like Creevey, because this farm in western Kansas was flourishing. Much more of it lay fallow than would be permitted in Iowa, but the fields that were working were performing miracles.

The other visitors were equally impressed, and all wanted to hear Dr. Creevey’s secrets. So after their inspection they assembled in one of the barns, where a blackboard was set up before rows of benches, and when they were settled, a representative from the Rock Island Railroad rose, and with a piece of chalk in his hand, said, “Gentlemen, I am going to place upon this board the one irrefutable fact about this wonderful farm you have just inspected.” With that he wrote a huge 14. “There it is, gentlemen, the basic fact you must remember as long as you are with us. On this land, only fourteen inches of rain falls a year. We have no irrigation, no tricks. Only the genius of this man, Dr. Thomas Dole Creevey.”

The little doctor walked to the board, his vest unbuttoned and his eyes flashing. “I affirm,” he said in his lowest voice, “that any man in this room who follows the principles I have delineated can move onto any land in the west, if it have topsoil and at least twelve inches of rainfall a year, and duplicate what you have just seen.”

Bursting with enthusiasm, he jumped around before the blackboard, jabbing his right forefinger into the faces of men in the front row as he laid forth the ten principles which would revolutionize the west.

“One, the whole secret is to catch, store and protect from evaporation whatever rain falls on your land.

“Two, you can never catch and store enough in one year to grow a good crop. Therefore, you must allow about sixty percent of your land to lie fallow. If you’ve been farming eighty acres in Iowa, plan to farm at least three hundred and twenty out here. And allow most of it to rest and accumulate water.

“Three, you must know your soil. Don’t move a foot west of Iowa without an earth auger. It looks like this and enables you to bore beneath the surface and see what’s going on. How deep the topsoil is, how wet.

“Four, keep a mulch of some kind on your fields throughout the year, for this will prevent what moisture you do get from evaporating. You must never allow even one drop of rain to escape.

“Five, whenever it rains you must do two things. Fall on your knees and thank God. Then jump up, harness your horses to the disk and turn the field over while the last drops are falling. This will throw a mulch that traps the water. If you wait till tomorrow before you disk, half the water will evaporate.

“Six, plow in the fall. If you keep a small family garden, you will naturally want to plow that in the spring, but plow your big fields in October and November.

“Seven, plow at least ten inches deep. Then disk. Then harrow.

“Eight, plant your wheat only in the fall. Plant only Turkey Red.

“Nine, after a field has lain fallow for a year, it’s a fine idea to raise a crop of lucerne or milo and plow it under. This roughage aerates the soil, adds nitrates and enriches.

“Ten, farm every day of your life as if next year would see the drought.”

As he finished his decalogue he clasped his hands in front of his round belly and bowed his head. He knew that he was asking inexperienced men to engage in a dangerous gamble, and some would be so faltering in courage that they would fail; for them he felt deep sadness. But he also knew that some of his listeners were men of determination like the pioneers who had settled this land originally; for them he felt an abounding joy. They were about to enlist in a great adventure, and he knew they could succeed.

In the quiet barn he delivered his challenge: “I do not offer you men an easy life. I offer you riches if you will work. I do not promise your wives a life of ease. I do promise them partnership in the last great challenge of this land. And to husband and wife I offer that divine promise so beautifully expressed in Isaiah 35:

The wilderness and the solitary place shall be glad for them; and the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose. It shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice even with joy and singing … Strengthen ye the weak hands, and confirm the feeble knees … for in the wilderness shall waters break out, and streams in the desert. And the parched ground shall become a pool, and the thirsty land springs of water …

In the next three days Dr. Creevey demonstrated each of his principles, showing how to use the earth auger and the mulch and the system of summer tillage. Since it did not rain during their visit, one morning he said, “We shall make believe that rain falls at ten o’clock, because you must fix in your minds what to do when it does.”

So at ten a small sprinkler was hauled onto one of the fallow fields, and four horses dragged it back and forth for an hour to show how far the water would penetrate. As soon as they left, Dr. Creevey shouted, “Rain’s over!” and he hitched four other horses to his disk and proceeded to turn over barely four inches of the moistened soil, throwing it to the bottom of the furrows where its water content would be protected from evaporation. He then unhitched his team, fastening them to a harrow, with which he smoothed the roughened field. In this way the rainfall was conserved.

“When I plow this field in October,” he told the men confidently, “and plant it with Turkey Red, I am assured a crop, even if no moisture falls during the winter, for I have trapped the moisture down there and it lies waiting. The only thing that can injure me is a sudden hailstorm.”

At the end of his exposition he placed before his visitors his farm accounts for the past five years, and they could see for themselves what he had accomplished on this Kansas farm, on the one near Denver, Colorado, and on the one in California. There were the rainfall records; there were the crops harvested; there were the funds deposited in the bank. One hundred and thirty-one farmers were satisfied that it could be done, and more than ninety were prepared to follow in his footsteps. Their plows would tear apart the sleeping west. Of the ten principles Creevey had expounded, nine would have permanent applicability; only one was defective, and this only because he had failed to take into consideration the interaction between it and a natural phenomenon which swept the plains at rare intervals.

During the first twenty years of his experiments, the nature of this fatal deficiency would not become apparent, but when it did, it would come close to destroying a major portion of the nation.

On the train back to Ottumwa, Earl Grebe was preoccupied with the task of convincing himself that he ought to leave his farm in Iowa and take the risk of dry-land farming farther west. He was a cautious man, and the idea of leaving the fields on which he had been raised was distressing, but since he had worked them for some years without moving any closer to ownership, he was receptive to any solution which promised improvement. Magnes Volkema was certain that Colorado was the answer.

“Look at the pictures,” he told Grebe. “Same kind of land, same kind of results.”

They studied the sixteen-page pamphlet which Creevey had distributed as they boarded the train. It detailed the rich future that awaited any man who bought a dry-land farm in the vicinity of Centennial, Colorado. The wheat was tall. The furrows were straight. The pages were filled with photographs of expensive homes that had been built by enterprising men and women who had moved west. Pages of statistics showed what the rainfall was and how long the growing season, but the persuasive portion of the brochure came in the words of the man who had compiled it. The photograph showed a frank, sincere businessman in a dark suit, sitting at his desk beneath a shiny new sign which said:

Slap Your Brand on a Hunk of Land

MERVIN WENDELL

RANCHES AND ESTATES

Wend Your Way to Wendell

Below the reassuring portrait were the words: “In 1889 I arrived in Centennial penniless, but through the prudent purchase of irrigated farmland, I now own the palatial residence portrayed on the opposite page. You can do the same with your dry-land farm.” The photograph showed a fine new mansion at the corner of Eighth Avenue and Ninth Street, with Mervin Wendell standing on the lower step and looking up fondly at his handsome wife on the porch. It exuded success and stamped Real Estate Agent Wendell as a man to be both trusted and emulated.

Grebe and Volkema were particularly interested in the map of the region open to the lucky families who moved west, for it showed where the proposed new town would be located. “Line Camp,” the brochure said, “soon to be the Athens of the west. The school will be housed in this fine building, facing this edifice in which the civil officials will maintain their headquarters.” The photograph showed the two stone buildings built there by Jim Lloyd back in 1869. They were sturdy and clean and the years had not marked them. They sat solidly upon the plains, lending an impression of permanence and promise.

“The land office will be housed here,” the brochure promised, “and all you have to do is go onto the prairie, locate the 320 acres you prefer, and claim it for your own. Three years to a day from the moment you step foot on your chosen land, it’s yours, and you’ll have a paper signed by the President of the United States to prove it.”

“Can you imagine owning 320 acres like the ones Dr. Creevey had?” Volkema asked. “A man could make his fortune on that.”

Grebe was looking at the photograph of a dry-land farm operated by a man named John Stephenson, who, the caption maintained, had come to Centennial penniless in 1908, had purchased some land from Mervin Wendell and now lived in a palatial home. The land looked good and the wheat was tall.

“He wouldn’t dare lie about this, would he?” Grebe asked suspiciously.

“No! When we get to Centennial and ask, ‘Where is Stephenson’s farm?’ Mr. Wendell’d be in real trouble if there wasn’t any such farm. This is real, Earl. People are making their fortune out there, and you and I ought to be part of it.”

So the two men studied the seductive publication, and the more they saw, the more convinced they became, so that by the time their train reached Ottumwa they were not reporters, they were missionaries, and each man went home to talk to his wife and neighbors.

Alice Grebe was a tall, thin young woman of twenty-two. She had been reared on a farm east of Ottumwa, one of seven children of deeply religious parents, and Earl had met her at church. He had courted her over a period of three years, and when he formally proposed, at first her parents seemed reluctant to let her go, even though their home was crowded. But her father and older brother launched an inspection of Earl’s life and came away satisfied that he was worthy to join their God-fearing family.

The wedding had taken place only the year before, with three members of Earl’s family in attendance and nineteen of Alice’s. As she stood before the minister she looked more dedicated than radiant, for she was not a beautiful girl. Her quality lay in her capacity for work and her desire to found a Christian home. The women of Ottumwa who watched as she pledged her vows concluded that here was a girl who would give her husband little trouble and much support. She was, indeed, an ideal wife for a young farmer, and the fact that she preferred rural life enhanced this promise.

This first year of marriage had been close to perfect, because each honestly sought to be a good partner; their only disappointment stemmed from Earl’s inability to acquire a farm of his own. Iowa prices were simply too high, and the young couple had to content themselves with leasing a farm owned by a banker in town. They inspected several farms up for sale but could not meet the required down payments and had resigned themselves to working for others when Dr. Thomas Dole Creevey arrived in town.

Alice Grebe had been the first to see the announcement and it had been she who had encouraged her husband and Magnes Volkema to attend the first night’s lecture. On the second night, when Dr. Creevey promised to get down to specifics, she and Vesta Volkema had sat near the front, and it was partly because of their visible enthusiasm that the audience had nominated their husbands to take the trip west to investigate Creevey’s experimental farm.

“It’s all he promised,” Earl reported as they sat together after supper. “Look at these photographs of the land we get free in Colorado.” When she saw the alluring pamphlet, and the friendly countenance of the real estate man who was volunteering to help them acquire land around the new town he was planning, she experienced the same excitement that had gripped her husband when he had first seen the publication.

“It looks just fine,” she said, turning the pages.

“You wouldn’t believe what Dr. Creevey accomplishes on land just like this,” Earl said, and he went on to explain Turkey Red, that fine winter wheat imported from Russia, and the clever new ways of trapping moisture.

She was not listening. Her eye had fallen upon the one photograph Mervin Wendell had fought against including in his pamphlet. “You’ve got to show them what the land looks like,” the railroad agent had insisted. “I don’t want women looking at those bleak empty spaces,” Wendell had said with the prescience that marked his dealings. “You show a bunch of Iowa women those prairies, and they’ll panic.” Against his better judgment the dry-land photograph had been included, and now as Alice Grebe looked at it, she had a premonition of the loneliness she could expect and the dread silence at night with no human being within earshot, and she was no longer sure they should embark on this adventure.

“Are you all right?” Earl asked, seeing her grow pale.

“Of course,” she said weakly. “It looks to be wonderful land.”

“I want to move west,” he said. “I want to work where I can own my own place.”

It was the timeless cry of the man who dreamed of moving on, of leaving old patterns which circumscribed less venturesome men. It had been voiced at every stage of American development and had motivated the most diverse types of men: the renegade trapper, the devoted Mormon, the feckless son, the daring entrepreneur, the young woman without a man or a prospect of one, the housewife who wanted better things for her husband. It was the authentic vision of the pioneer American, the dream of freedom and more spacious horizons.

In the early years of the twentieth century this eagerness to move westward reached its height. New immigrants from Europe who did not wish to be trapped in city slums caught the train to Chicago and from there to the wheatfields of Dakota and Minnesota. Old residents of the Atlantic seaboard who sensed that this might be the last chance for a man to live more freely heard of unclaimed lands in Colorado and Montana and made the break. Young ministers, middle-aged hardware merchants and old roustabouts joined the movement, while a score of different railroads sent persuasive men into all towns preaching the doctrine of free land in the west. It was a conscious movement and the people who participated were among the finest and strongest citizens America had yet produced.

Alice Grebe stifled her fears. If her husband longed to hazard new fortunes, like the hero of a book she had just finished, she must encourage him. And in the last days of summer, 1911, two families from Ottumwa reported to the station for the journey west: Earl and Alice Grebe and a crafty older pair already familiar with emigration, Magnes and Vesta Volkema, accompanied by their two teen-age children. A few men in the crowd that bade them farewell said, “I wisht I was younger so’s I could go along,” and Vesta Volkema told some of them, “You’re younger right now than I am.”

They went to Omaha, and caught the train there which would take them to Centennial, where Mervin Wendell would be waiting. And as they sat in the coach through the long night while the train crept westward through Nebraska and across the border into Colorado, they talked of their bright future.

“It’s a new start,” Alice Grebe said with an animation she did not wholly feel. “Like the ox-cart women of a hundred years ago. It’s really quite thrilling.”

“It’s a chance to pick up a few easy dollars,” Vesta Volkema said. “I want to get hold of as much land as possible as quick as possible. Sell at a profit. Then on to California.”

“I see it as an opportunity to establish a home,” Alice Grebe said. “Our own town … maybe watch one of our sons become mayor.” She leaned forward as she spoke, as if eager to begin this new contest with the land, and once she reached out to touch her husband’s hand, reassuring him that she was ready for whatever the new challenge presented. “I can hardly wait to see our new home,” she said.

“Our families will build the church,” Alice said prophetically. “And we’ll put our books together to build a library.”

“You’re looking too far ahead,” Vesta teased. “What I’d like to see is a good grocery store.”

“We’ll get one,” Alice said. She had been valedictorian of her class in Ottumwa, a very bright girl who should have gone on to college, her teachers said. She read books by Upton Sinclair and visualized an always-better society. In her graduation address she had declaimed: “We are the builders of tomorrow. We are the new pioneers.” At the time she drafted those words she had been only vaguely aware of their import, but now as the train rattled toward Denver and the great mountains she felt as if she were the very spirit of a pioneer movement, and she reveled in the excitement of what lay ahead.

“It’s so thrilling!” she whispered to Vesta. “There can’t be another pair on this train as fortunate as we.”

But when dawn broke and she saw those interminate plains west of Julesburg, those prodigious reaches of loneliness, gray-brown to the horizon without tree or shadow, the enormousness of their adventure overcame her, and she fell into such a trembling that Vesta had to grasp her hands and quieten her.

“Earl! Come here!” Vesta called, and when Grebe sat with his wife he said, “She’s only nervous,” but Vesta sized the situation up more accurately. “She’s pregnant,” she said matter-of-factly, and when she confronted Alice, the girl confessed that she had known for several weeks but had told no one lest the trip west be canceled.

“It’s an omen,” Earl told the group. “Just like the Bible says: ‘Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.’ Those are the first words God ever spoke to man.” He sat with Alice’s hand in his and looked out at the lonely land. “We shall multiply,” he said, “and we shall subdue.”

Mervin Wendell rose early that morning. In the years when he sold irrigated farmland, he had learned to be at the station whenever settlers arrived, for he had found that in their first hours in Centennial they were likely to require his reassurance in a variety of ways, and if he signed them up early, they stayed signed. Now that he was trying to peddle drylands, it was even more important. He therefore shaved by the new electric light which graced his mansion, then doused himself with real French eau de cologne shipped in from Boston. He trimmed the hair about his ears, using his wife’s scissors, and slipped into his western outfit: whipcord trousers, Texas boots adorned with silver, pale-blue shirt with string tie, a wide-brimmed hat. Reviewing himself in the mirror, he felt satisfied that his figure was as good as ever and his jaw line still firm and in its way commanding.

The Negro cook waited with Mervin’s regular breakfast: sourdough pancakes, two eggs, three strips of bacon and a pot of hot coffee without cream or sugar. He liked the batter for his cakes to be kept watery, so that the resulting cakes were thin and very brown on each side. “Thick pancakes that taste like a blotting-paper sandwich are not my style,” he explained, and this morning they were done his way.

When he had eaten, he went upstairs to kiss his wife goodbye, advising her, “I’m hauling our first load of homesteaders out to Line Camp, and I won’t be back till late. Each man will want to tramp over his land, and I’ll be busy.”

He went downstairs and climbed into his new six-seater Buick, which he idled for some minutes before venturing out onto Eighth Avenue. The quiet purr of the motor pleased him, and slowly he engaged the clutch, releasing it with skill so that the gears meshed properly. With a restrained touch on the horn, he announced without ostentation that Centennial’s leading citizen was about to move down the street.

On this morning he was to experience a nasty shock, for when he reached the station he found Jim Lloyd and Old Man Brumbaugh already there, and he discovered that they proposed addressing the new settlers as they left the train.

“What about?” he asked with visible dismay.

“About land,” Brumbaugh said shortly.

“What about it? They homestead legally. I sell them additional land, which I own. What’s wrong about that?”

“The use of the land,” Brumbaugh said with impatience. “Have you no conscience?”

“It’s good land for wheat,” Wendell said pugnaciously, glaring at Brumbaugh. “It’s been proved you can grow wheat out there.”

“The sod crop,” Brumbaugh said contemptuously. “Any soil in the world will produce a crop first year the sod’s broken. You know that.”

“It’s the years that follow the sod crop that will break these people’s hearts,” Jim Lloyd broke in. “What are they going to do, Wendell, when those roaring winds blow out of the Rockies? You’ve seen what they can do to irrigated farms. What in hell would they do to dry-land crops?”

Wendell licked his lips and asked placatingly, “What kind of speech will you make to our visitors?” He did not try to override his two antagonists; from past experience he had learned that where land was involved, these men could be difficult. However, he did keep stored in the back of his mind a strong telling point against them, and if they tried to make real trouble for him, he intended using it.

“We’re going to warn the newcomers to go back home,” Brumbaugh growled. “We don’t want them to commit suicide on this barren land.”

“You’ve done pretty well on ‘this barren land.’ ” He mimicked Brumbaugh’s pronunciation, and the old Russian grew angry.

“I had water,” he said, turning away from Wendell and leading Jim Lloyd to a different part of the station platform.

They were talking together when the train pulled in, and they watched as this batch of families that Wendell had assembled from all parts of the nation came hesitantly down the steps. They were a handsome lot, men and women in their late twenties and thirties mostly, skilled farmers ready for the new challenge. Potato Brumbaugh felt his heart warming to these adventurous people, especially the women, on whom the terrors of the new life would fall so heavily. “Tears come in my eyes when I see them,” he told Lloyd. “The government should prevent this.”

One of the couples overheard this remark, and the woman shivered at the words and drew her husband closer to her.

“You settling here?” Brumbaugh asked them.

“Yes,” the husband said.

“What’s your name?”

“Grebe. Earl Grebe.”

“Listen to an old man, Earl …” Before he could issue his warning Mervin Wendell’s clear, reassuring voice sounded through the morning air.

“Over this way, ladies and gentlemen. I’m Mervin Wendell, the man who’s been writing to you, and I’ve rented these automobiles to carry you to your new homes.”

He moved in deftly, a figure of distinction and reassurance, saying precisely those things which the new families wanted to hear: “The land commissioner is in his office at Line Camp. He has plats of the new town we are going to build. More important, he has the surveyors’ maps showing the townships and the sections from which you can choose free land.” As he reminded them of the opportunity they faced, his voice assumed a kind of grandeur, and he held out his hands like an Old Testament figure leading his people toward a promised land.

The effect was somewhat destroyed, however, by Potato Brumbaugh, who muscled his way to the head of the crowd, seeking to warn them against the mistake they were making: “Good farmers, listen to me. You cannot make a living on the drylands. Men tried in the eighties.”

“They did not try Dr. Creevey’s new method,” Wendell said coldly.

“You’ll get good crops the first year, and you women will think you’ve found a paradise.”

“They have,” Wendell broke in.

“But that’s just the sod crop, and you know it. Think ahead to the dry years.”

“If we plant the way Dr. Creevey told us,” an Indiana farmer said, “there won’t be no dry years.”

“Some will be terribly dry,” Jim said. “And you’ve never seen the like of our Colorado windstorms.”

Mervin Wendell saw that Brumbaugh and Lloyd were beginning to have an effect on the newcomers, so he decided that the time was proper for him to counter their arguments. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said quietly, “these good men have every reason in the world to discourage you from claiming land that is rightfully yours. Mr. Brumbaugh came to Centennial years ago without a penny. He took up his free land to grow sugar beets, and now he’s a millionaire. Jim Lloyd, that cowboy over there, also arrived without a cent. He took up grazing land for his cattle, and now he’s a millionaire too.” Wendell dropped his voice and added slyly, “Of course, he married the boss’s daughter, and that never hurts.” He watched with aloof amusement as the two men squirmed.

“The situation is obvious, isn’t it?” he asked with scorn. “These men have all the land they need and now they wish to keep you from getting yours. Every word they utter is self-serving, because they want to keep everything for themselves.”

The charge was devastating, and Brumbaugh realized that anything further he might say would have no effect. He walked away from the young farmers and would have left the station except that a tall young woman ran to him, touching his hand. “Are you convinced we’re wrong?” she asked earnestly.

“You’re dead wrong,” he said.

“Because you’re destroying the grass. You’re tearing up the sod. It’s impossible to farm the land you’ll be choosing.”

“Dr. Creevey does.”

“He spends his whole life on the project. He has every kind of support from the railroad. But when the bad years come, even he will be wiped out.”

“You’re sure the bad years will come?” the young woman asked.

Brumbaugh looked at her, and she appeared to be the type of woman he had known decades ago on the Volga, hard-working, dedicated, whose soul would be shattered by the experiences that lay ahead. “Are you pregnant?” he asked bluntly. When she nodded in shy embarrassment, he said quietly, “May God have mercy on you, because the land won’t.”

“You’ve prospered, they say.”

“My farm was near water. Yours won’t be.”

Mervin Wendell called for the women to follow him, and the Grebes started to move away, but Brumbaugh caught Alice by the hand. “Go back home,” he warned her. “The land out there … it’s fine for dogs and men. It’s hell on horses and women.”

“Over here!” Wendell called. “You, young lady. In this car.”

And it was from the rear seat of a fancy Buick that Alice Grebe first approached her new home. Mr. Wendell, at the wheel of his own car, drove east on Prairie, then north past Little Mexico, where adobe hovels astonished the newcomers, and then northeast toward the proposed village of Line Camp. When the caravan crossed Mud Creek and entered the great plains, several women gasped at the total emptiness, for not one living thing could be seen except grass, not one sign of human occupancy except the winding road.

“My God, this is desolate!” Vesta Volkema cried.

“Not when it has barns and windmills and lovely homes dotted across the horizon,” Wendell said brightly. And now it became clear why he had crowded all the wives into separate automobiles; he did not want their disappointment to contaminate their husbands. The men would be looking at the soil, trying to estimate its worth, and if left alone, would reach favorable conclusions … or at least not negative ones. And later they would persuade their womenfolk to accept the decision.

“Wait till you see Line Camp!” he said enthusiastically.

“What’s it like?” Vesta asked.

He had purchased a section of land—640 acres—from the Venneford people for the establishment of a new town centered upon old Line Camp Three, long abandoned. With the land, he acquired the stone barn and the low-built one-story stone house which had been used by generations of cowboys when they worked the Venneford cattle. The buildings were the best part of the purchase, and with them as a focus, the surveyors had platted a western town, centered upon the intersection of State 8 and Weld 33.

A newcomer to Line Camp had three choices. He could buy land and live in town, or close to it. He could homestead for three years and get a half-section, 320 acres, free. Or he could start to homestead and after fourteen months buy the land from the government for $1.25 an acre.

Mervin Wendell encouraged as many people as possible to do the last, for as soon as they got legal title to the land, they were free to sell it, and he was prepared to buy as much as possible from them at $1.75 an acre, intending to sell it to later arrivals at $7.00 or $8.00. It was to his interest that as many as possible of the newcomers occupy their land for fourteen months and then quit, for in their failure lay his success.

With this first drylands group he was doubly sure that many would lose heart. The tall girl who had been talking with Brumbaugh—she wouldn’t stay long. Nor the minister’s wife, nor the young woman with two children. He had often bought homesteads from such defeated people for 25¢ an acre, and he would do so again.

So his tactic would be to encourage the families as fulsomely as possible while they were signing up for their free land, then to commiserate with them when they wanted to flee the area. He would work principally on the women, reassuring them at first, sympathizing with them when the bad years struck. And in this manner he would acquire huge holdings in the area, hovering always like a jackal about the edges of a camp, picking up the strays.

With horns blowing, the rented automobiles drove into the space between the two stone buildings, and Mervin Wendell climbed atop a wooden box to explain procedures: “This will be your new town. That stone barn is being converted into a first-class general store, where you will be able to purchase almost anything you could in Chicago. That round thing over there will climb ninety feet into the air and serve as the elevator where you will store your vast crops of wheat. Down there is where the railroad station will be. And this low building houses the land commissioner, who is going to give you all the acres you require. The free land extends in every direction, but I’ll tell you frankly, if I was choosing, I’d take one of those half-sections in the northeast sector, up beyond Rattlesnake Buttes.” Here he broke into an easy laugh, explaining to the women, “When Indians lived here, the Buttes had rattlers. Today no Indians, no rattlers. Today mostly Baptists, and they’re trouble enough.” At this joke the wives laughed nervously.

“The automobiles will sally forth in various directions, and you are free to inspect the land for as long as you like. When you’ve made your choice, you come back here and speak to my good friend Walter Bellamy.” From the interior of the building, he summoned the land commissioner, and a curious young man appeared, thin as a reed, red-haired, awkward and with a green shade protecting his pale-blue eyes from the incessant sun. He was twenty-four years old, a college graduate from Grinnell in Iowa. He was shy and deprecatory of his ability; he had come west to find escape from family pressures, and he loved the quiet job he had stumbled into as land commissioner. To watch people, day after day, choosing and settling upon new land would be exciting.

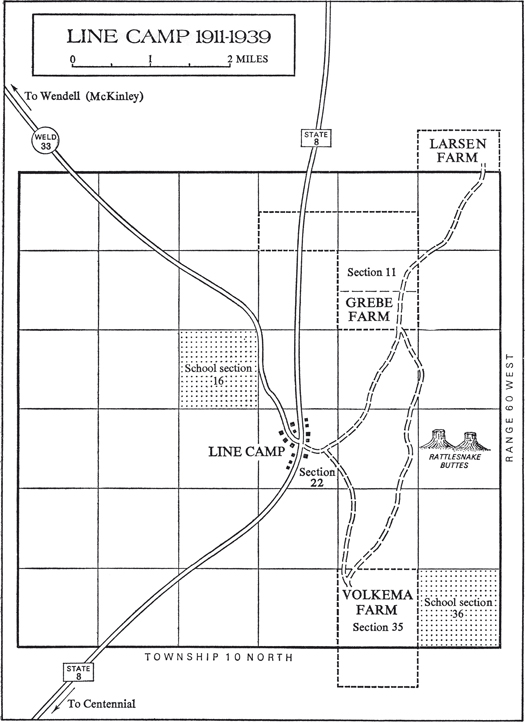

“Show them the maps,” Wendell said unctuously, and the surveys were unrolled: Township 10 North, Range 60 West, with the town of Line Camp occupying Section 22, and with Sections 16 and 36 reserved for the school district.

The farmers could see that most of the half-sections in this township were spoken for; what they could not detect was that most of them belonged to Mervin Wendell, who was ready to sell them at a profit. The free land lay farther out, and for some reason he could not have explained, Earl Grebe focused on land which lay to the northwest, and when he discussed this with the group, he found that another family, the Larsens, had done the same, so they procured one of the cars and drove along country trails to that section of the free land, but when Earl bored in with his earth auger, he brought up a very dry sample that showed a tillable depth of less than six inches.

“This isn’t for me,” he announced, and he went off on his own, and at the northeast corner of the township he found a half-section that had everything he required: rolling land for good drainage when the rains did come, a topsoil fourteen inches deep, fairly good moisture already in the soil and a view of the two red buttes to the south, with absolutely nothing but low hills visible in any other direction. He saw this as a majestic land, worthy of a man’s best efforts.

“Alice!” he shouted to his wife. “Look at this!” And he showed her the dimensions of the land the government would be giving them. It seemed a vast holding, 320 acres, with enough to leave a large part fallow year after year, and a protected hillside behind which a house could be sheltered.

Alice stood by her husband, staring at the huge land they were about to occupy, and whether it was a chill or her pregnancy or a foreboding of what the years might contain, she began shivering, for this seemed to her the bleakest land that God had ever given His children to plow. Earl, sensing her fright, placed his arm about her and promised, “It’s our task to subdue this land and make it ours.”

He handed her his notebook and asked her to jot down the designation of their new home: “Township 10 North, Range 60 West, Section 11, the south 320.” When the figures were written, Alice found in them a sense of reality, and her apprehension abated somewhat. Bending down, for she was slightly taller than her husband, she kissed him on the cheek and said, “I’m all right. The place is so empty, it seems filled with ghosts.” To Earl such a statement was incomprehensible, and he made no reply.

The Larsens found a good piece of land in Township 11, a little farther north, but the Volkemas located a fine half-section to the southeast and staked out two additional half-sections to which they were not entitled. When the group reassembled outside the land commissioner’s office, Alice asked, “What are you going to do with the extra sections?” and Vesta said, “Don’t worry about that, I have the chalk.” This reply made no sense at all, so Alice turned and asked Mrs. Larsen, “What does she mean?” and Mrs. Larsen said, “She looks as if she knows what she’s doing.”

With the others watching, Mrs. Volkema directed her son, aged seventeen, and her daughter, eighteen, to take off their shoes. With her chalk she wrote on the inner sole of each shoe: “Age 21.” Then the two children put their shoes back on and accompanied Vesta into the land office, where Commissioner Bellamy waited with his maps.

“Have you located the land you prefer?” he asked formally.

“We have,” Earl Grebe replied, and he proceeded to designate what he and Alice had chosen. Papers were signed, and Bellamy said, “You have staked your claim as of this date. Within six months you must give me proof that you have taken up actual residence on your land. If you fail to do so, you forfeit your claim. On the other hand, if you pitch a tent today and take up residence, three years from this date the land is yours, fee simple. Are these terms understood?”

“How do we inform you that we’ve taken residence?” Grebe asked.

“You come in here and tell me so. You put your hand on that Bible and swear to your occupancy, and that’s good enough for the government, because we know you’re all Christian persons.” And in this simple manner Earl and Alice Grebe filed their intention of homesteading.

With the Volkemas the routine was somewhat different, for after Peter and Vesta had filed for their 320 acres, they nudged their son to step forward. “I’m filing on the 320 north of my father’s,” the boy said, and Walter Bellamy’s jaw dropped a couple of inches, for the law required that a homesteader be twenty-one, and this downy-cheeked lad looked as if he were about eighteen.

But before Bellamy could protest, the Volkema girl stepped forward, a slim child who could not possibly be over twenty-one, and she filed on the 320 south of her parents’.

“Are you young people over age twenty-one?” Bellamy asked and they, knowing that they were standing above the “Age 21” written in their shoes, replied “Yes, sir.”

This was too much for Bellamy, so he produced his Bible and made them place their hands on it, after which he asked in a funereal voice, “Do you solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God that you are over age twenty-one?”

“I do,” the boy said.

“I am,” the girl said.

“Well, there’s nothing more I can do,” Bellamy shrugged, and he entered their claims. The Volkemas now had a grasp on 960 acres, and they intended acquiring much more.

The Homestead Act of 1862 as amended in 1909 required a settler to erect a house at least twelve feet by fourteen feet, and this was customarily referred to as “a house twelve by fourteen.”

The Volkemas, therefore, carved a little wooden house twelve inches by fourteen inches, and four weeks later when they appeared at Bellamy’s office to announce their occupancy of their land, they assured him that they had a house twelve by fourteen. So did their son. So did their daughter. And Bellamy had no alternative but to enter their proof of occupancy.

The Larsens chose an alternate course. Some years before, Mervin Wendell had directed his carpenter to build the flimsiest possible kind of house, twelve by fourteen feet, on a sledge which could be hauled from one homestead to another. He rented it to newcomers—five dollars for twenty-four hours—and with it perched on their claim, they could swear that they had on their half-section a house twelve by fourteen. As soon as their assertion was recorded, the sledge could be hauled to the next homestead.

The Grebes would not engage in such deception. For them to have sworn to a lie would have been inconceivable, for they believed that God inspected all they did and that only through His assistance could something like their present venture succeed. So they refused Mervin Wendell’s offer of the house-on-the-sledge and Vesta Volkema’s kind gift of the carved house. Theirs they would build the honest way.

Earl purchased two wooden doors, two door sills and three window frames. The carpenter delivered them to the half-section, where Grebe and two boys from the village were cutting sod for the walls and collecting flat stones for the floors. When the materials were assembled, Grebe and the boys rode into the low hills north of Rattlesnake Buttes to find lodge poles and rafters, and at the end of two months of arduous work, the Grebes had themselves a soddy.

It was not a neat-looking house, for the earth was uneven in form and color, but it was surprisingly snug, a low, compact refuge which gave solid protection from the wind and such occasional rain as might fall. When the house was ready for occupancy they invited a clergyman from Centennial to bless it, and he appeared with Walter Bellamy in tow, and a solemn service was held.

It was exciting, this launching of a new life, but that night Alice Grebe suffered the consequences of the heavy obligations she had undertaken. Toward evening she fell ill, and before anyone could be summoned from the neighboring ranches, she miscarried. Her husband was grief-stricken. He sat with her through the remainder of the night as the first winter wind whipped at the soddy, and when dawn broke he walked heartbroken across the plains to the Volkemas’.

When they heard the sad news, Vesta went back with Earl. She assured him that Alice was a strong woman and would produce numerous future children. There were no complications that she was aware of, but consulting a doctor might be a prudent safeguard. The nearest one was in Centennial, and Walter Bellamy volunteered to take Alice in to town, and as Vesta had predicted, the doctor found nothing wrong, and that night Alice was back in the soddy.

“You must see that she doesn’t fall into a depression,” Vesta had warned, but of this there was no fear, for Alice herself had foreseen that danger and now plunged directly into the tasks of making this soddy into a true Christian home.

There was a library at the college in Greeley, and from it she procured books by Edith Wharton and Lincoln Steffens and a new treatise on dry-land farming by a Dr. Widtsoe. She studied this with care, in order to help her husband, and took much consolation in the portrait of Jethro Tull, a stout Englishman in a copious wig who had proved that a family could be successful on a dry-land farm.

“It seems so strange,” she told her husband, “to be growing things I’d never heard of six months ago. What is milo?”

“A sturdy type of sorghum.”

“What’s sorghum?”

“A sturdy type of sugar cane.”

“We don’t make sugar.”

“We plow it into the ground. Roughage. Aeration.”

“And lucerne? Never heard of it before.”

“That’s a sturdy form of alfalfa.”

“Everything in this land must be sturdy,” she said. “I’ll be so, too.” And two months later she was pregnant again.

When the spring crops of 1912 were well up, and a bountiful harvest seemed assured, she heard a strange rattling in the fields, a sound she could not identify, and she ran to the door of the soddy to behold a devastating hailstorm sweeping eastward from the mountains. The ice pellets were as large as hen’s eggs and they fell with such terrible force that she had to retreat from the door lest the hail strike her and endanger her child.

In the eleven minutes the storm raged across the prairie, it knocked flat every growing thing. When it passed, the fields were desolate, and that night Earl Grebe wondered if he would make a crop at all. The Volkemas came by to see what damage the Grebes had suffered; by a trick of nature the storm had concentrated on a small path to the north of Line Camp, so that the Grebes were pretty well wiped out while the Volkemas were practically untouched.

“I’ve had a lot of experience with hail,” Vesta said, “and thank God this storm came early. Tomorrow you’ll plow under the dead crops and still have time to grow summer wheat. The milo and the lucerne will fertilize the fields and all you’ve lost is some time and some seed.” She and her husband helped with the plowing, and whereas the summer crop was not as good as the winter one would have been, the Grebes did make some money that year.

It was the sound of the coyotes that tormented Alice, and one lonely night in October when her baby was about to be born and Earl was helping out on another farm, she heard the ululating cries in the darkness, and they sounded to her like the voice of doom. She fell to violent trembling and was seized with a strong premonition that something fearful was about to happen, but she steeled herself against the night, and kneeling beside the bed, she prayed for strength to bring this pregnancy to its proper conclusion.

“Oh, God, help me through this dark autumn. Help me to be strong.”

When Earl reached home he found his wife on her knees beside the bed. “I’m having the baby early,” she whispered.

“Right now?” Earl cried.

“No. Maybe three hours … four.”

“I’ll fetch Vesta,” he said.

When Magnes and Vesta reached the soddy, they found Alice so far advanced in labor that any thought of taking her to Centennial was vain. “Do you know what to do?” Earl asked Vesta, and she said, “It’s nothing,” and she produced her book of home medicine. With much fumbling and more mess than necessary, Alice Grebe was delivered of her baby, a boy whom she named Ethan, after a character in a novel by Mrs. Wharton.

For Alice, the hardship of life in the soddy was relieved by the constant variations she saw in the prairie. “At first I thought it was all emptiness,” she once told Vesta. “Then I started watching birds, and the hawks and the redwings became more beautiful than the flowers back home. I heard the meadowlarks and one day I watched the courtship performance of the sage grouse … the males had their white chests all puffed out … and I could see strange-looking yellow air sacs on their necks, while their tails were spread sort of like a peacock. It was something.”

Near the Grebe soddy a town of prairie dogs had existed for more than three thousand years, and it accommodated itself easily to the arrival of human beings, the antics of the little animals providing much amusement for Alice. More dramatic things happened, too, like the sudden, heart-catching sight of antelope as they leaped mysteriously from the buttes, dashing past the soddy to disappear to the north, winged things, fragile and fleet.

In October 1912 the last surviving buffalo in Colorado drifted into Blue Valley. It was an old cow that had been hiding in the hills back of the mining camp. How she had escaped wolves, hunters and starvation, no one knew, but she had struggled on, the last of the herd.

She was a heavy beast and required much grass during the year. She would have preferred ranging the plains, as her ancestors had done, but with the coming of settlers and the establishment of towns like Line Camp, this was no longer possible. She therefore hid in the mountains, foraging on the lush vegetation which appeared in remote valleys.

In summer she ate as much as she could; in winter she lived off her fat plus such dried grasses as she could uncover beneath the snows. In blizzards, she still used the ancient tactic: stand firm, lower the head and swing it back and forth like the bucket on a steam shovel until the grass was exposed.

The winter of 1913 brought much snow, and she had worn herself out pushing it away, but when she got down to the grass, it was good, and she had survived nicely. A warm spring followed and a rich summer, and she was fat. She had not enjoyed foraging alone, for she had always been a gregarious creature, but during the recent years of loneliness she had grown accustomed to her lot.

And then, by an unfortunate accident which might not have occurred had she been younger and able to detect the danger, she came over the crest of a hill at dawn to find herself in the backyard of a hunting lodge.

“Jesus Christ!” Jake Calendar called back to his friends. “A buffalo!”

He and four other men had come hunting the mountains—for deer or elk; if nothing better, antelope, with always the chance of a bear. Now, at Calendar’s cry, they all rushed to the window, and saw near the top of the hill behind the cabin a buffalo—and it was a big one.

“Throw me my gun!” Jake said in a low, controlled voice. He stood watching as the old animal, sensing no danger, kept coming down the hill.

Inside the cabin the four other hunters slipped into their shoes, not even bothering with pants, and within a few moments went outside, each with a loaded high-powered rifle. Silently the men lined up and took sight. “Take it slow,” Jake warned. “It ain’t easy to kill somethin’ that big.”

“One … two … three!” Jackson Quimbish did the counting, and when his voice uttered the last number, the five men fired in unison.

Quickly they reloaded and fired again.

Reloading for the second time, they blazed away once more at the astonished old cow. At the first fusillade she had stopped, then stubbornly had plodded on, keeping her massive head directed toward the creatures she could not see.

Since she was coming head-on, the hunters could not easily strike her in a vital spot, but the second five shots did some damage, and she stumbled, kicking up dust. Her eyes were blurred, but still she kept moving forward, an old, old cow, heavy in her knees. She was not afraid and showed no inclination to turn away from her adversaries, but she had no concept of how to cope with them. She merely kept moving forward.

The last fusillade struck her from two sides and her legs began to cave in. She tried to take a deep breath, but something stuck in her lungs, and in desperation she started to fall forward. Now her whole massive body surrendered and she tumbled into the autumn dust, sliding sideways down the hill for a few feet, then coming to rest against rocks.

When the sportsmen reached the body, five men in nightshirts and Jake Calendar barefooted as well, they judged that fifteen shots had struck the animal, but as Jake pointed out, “Six, seven must have hit her in the forehead, and hell, anyone knows that with all that matted hair and bone, you can’t kill no buffalo by hittin’ it straight on.”

In 1914 the plowmen’s championship was held on a bright October day on a ranch some miles north of Little Mexico. Farmers convened from all parts of northern Colorado to compete, and Line Camp was represented by Earl Grebe, who stood a good chance of carrying off first prize.

His four horses were in fine condition, their harnesses oiled and polished and their bellies filled with just the right amount of oats. Earl himself was well rested and prepared to do his best.

There would be nineteen competitors, and the field they would plow was an eighth of a mile square, with enough gentle dips and swells to provide a good test. The ground had never been plowed before; it was virgin sod and would not turn easily. Rules required that the nose of the plow must cut at least seven inches into the soil, so that weak horses would be of little use, for it required four of the strongest to cut that deep into unbroken sod.

The plowmen were required to demonstrate their skill with three farm implements: plow, disk, harrow. With the first the men had to cut to the proper depth, maintain an absolutely straight line and turn uniform furrows. With the disk they had to chop the sod. With the harrow they had to pulverize it and smooth it. Only experienced farmers could perform these various tasks, converting rough virgin earth into a tractable soil ready for the planting drill.

The plowmen worked simultaneously, each on his assigned portion of the field, and time was a factor, although not the determinant one. If two men plowed equally well, the one who finished first won, but no points could be gained by galloping the horses through the tasks, for crooked furrows did not count.

It was an exciting contest, one which drew several hundred spectators, many placing bets on their favorites. When the nineteen teams of horses were lined up behind the shining plows, with the disks and harrows waiting behind, one caught a sense of the prodigious undertaking the men of the west were engaged in: from Minnesota to Montana, from North Dakota to the plains of Texas, land that had never before felt the plow—not even the forked stick of the Indian—was being broken.

At ten o’clock the men in charge called the contestants to order, and the nineteen stalwart farmers grasped the handles of their plows, the reins draped about their necks. “Men,” the starter shouted, “it don’t need me to tell you no rules. Plow deep, plow straight, and change your hitches to the disk and harrow as fast as possible. You’ve got to pull each piece of machinery back behind the line before you unhitch. Ready? Go!”

It was difficult for the spectators to ascertain who was winning, because only the judges could allocate points, and they kept their conclusions to themselves, but from the lovely straightness of Earl Grebe’s furrows and their extraordinary uniformity, it was clear that he had a good chance.

But at the far end of the line there was a Swede with almost no neck, a little rock of a man, and his ability to identify with his horses was uncanny; with them, he formed a team of five, sturdy, hard-working animals who knew what they were about, and it was a joy to watch them move up and down the furrows in unison. The man’s name was Swenson, and he could use the disk just as capably as he used the plow.

But when it came to harrowing, no one could excel Earl Grebe. He was capable of putting a fine finish on the roughest terrain, and as the contest neared conclusion, the spectators knew that the winner would be Grebe or the little Swede.

There was silence as the four judges walked back and forth along the plowed stretches, comparing the evenness of the earth and the uniformity of the topsoil. “I think Earl has it,” Vesta whispered as the judges convened, and Alice kept her fingers crossed as the chairman stepped forward.

“The winner! Ole Swenson of Sterling.”

Alice looked down at the ground to hide her disappointment, then felt this to be an unworthy escape. Looking up with a bright smile, she winked at Earl as the judges proclaimed him the runner-up. He won the affection of the crowd by stepping back and patting his horses, giving them all the credit for the good work.

There was much cheering, and money prizes were handed out, and other farmers congregated about the two winners, congratulating them on jobs well done, and Walter Bellamy moved from one group to another, saying with obvious delight, “Wasn’t it splendid? A little town, Line Camp, winning second place? I’m really very proud.”

Two witnesses to the contest were not impressed. When the others had departed, they remained behind, staring at the plowed strips, each covered with harrowed earth almost as fine as the grains from a river bottom.

“It’s unnatural,” Potato Brumbaugh grumbled as he inspected the soil. “This land was intended for grass. If they abuse it this way, there’ll come a day of reckoning.”

Jim Lloyd stooped down to compare the uncut sod with the plowed, and what he saw appalled him. “It’ll take five years for this to grow grass again,” he said angrily. “They must be insane.”

“It wouldn’t be so bad,” Brumbaugh growled, “if they didn’t harrow it at the end. If they left the clods unbroken, maybe the land could save itself. But this way! Good God, all they’re doing is manufacturing dust.” He kicked at the offending soil and sent its pulverized fragments spinning in the sunlight.

“We had a good system here,” Jim said, “and they couldn’t recognize it. They had to tear the sod apart.”

“One thing I’m glad about,” Brumbaugh said with resignation, “I won’t be here to see the reckoning. I’ve worked harder than those horses to till this earth, the right way. I’ll be glad to be in my grave when the wrong way comes to grief.”

His lament was not heard by those who should have listened, for they were all now at the Railway Arms, discussing the victors and the good fortune that had come to wheat farmers generally. As Ole Swenson, the winner, proclaimed in his toast, “If them Germans and others keep fightin’ in Europe, sure as hell we’re gonna see two-dollar wheat. So come November, I’m gonna break an additional 640 and plant it in Turkey Red. If the war keeps on long enough, we’ll all be rich.”

Toward the end of November 1914 the Grebes became eligible to prove-up their half-section, for they had complied with the three major requirements: they had lived on the land for three years; they had built a house twelve by fourteen; and they had cultivated the soil. For five dollars Walter Bellamy would advertise in the local paper his intention of awarding the Grebes title to their farm, and in due time they would receive from Washington a legal paper, signed by President Wilson himself.

“You understand,” Bellamy told them when they gave him the five dollars, “that President Wilson himself doesn’t do the signing. It looks as if he did, but I’m sure he has a girl in the White House who can imitate his signature. Stands to reason, he’d wear out his fingers.”

On proving-up day the law required the applicant to bring to the land commissioner’s office two trusted friends who would testify that to their certain knowledge the said Earl Grebe had lived on his land and cultivated it. Grebe chose Magnes and Vesta Volkema, and when the three stood before Commissioner Bellamy, he warned them, “I shall interrogate each of you in private. You will be sworn on the Bible, and what you say will be recorded.” He pointed to Grebe and told the others to wait outside.

Bellamy took his job seriously and made the transfer of government land an impressive ritual, one that conferred dignity as well as title.

“What crops did you raise?”

“Wheat, milo, lucerne and a little speltz for the cows.”

“During 1913 what months were you in residence on your claim?”

“Not a day off it.”

“In 1912 what other members of your family resided there?”

“My wife, Alice. My son Ethan. But he was there only the last two months.”

“Where had he been previously?”

“Not born yet.”

“Have you a house at least twelve by fourteen?”

“Bigger.”

“You may stand aside, Mr. Grebe.”

Bellamy then summoned the witnesses, each by himself, and probed into this history of the Grebe holdings, and after a while he called all three before him. “I find that Earl Grebe did stake out a legal claim on his half-section, did occupy it, did cultivate it and did erect thereon a residence. If you have twenty-two dollars, Mr. Grebe, I will give you a receipt and the land is yours, fee simple and forever.”

“When do I get the deed?”

“That will be sent you by President Wilson. The land is yours.”

It was the custom in Colorado for a successful claimant, on the day his ownership was affirmed, to invite his witnesses to the local hotel for dinner, but Grebe was so relieved at gaining actual title to his land that he felt expansive. “Mr. Bellamy,” he said, “I’d be proud if you’d join us.” Bellamy, a bachelor who usually ate alone, accepted eagerly, and this inspired Mrs. Volkema to whisper to him during dinner, “You know I have a daughter with 320 acres in her own name. One of these days Magnes and I will be heading for California, and who knows? She may inherit our land, too.” Mr. Bellamy chewed away on his fried steak and appeared not to have heard.

The dinner was made memorable when the waitress interrupted to inform the guests that it was snowing outside, the first real moisture of the new planting season. The farmers left their drinks to gather at the window and watch with approval as flakes covered the earth and accumulated in drifts. “It’s going to be a good year,” Magnes Volkema said. “Maybe the best we ever had.” The two families now owned their farms and were prepared for the good fortune that the war was bringing them. This snow, enriching the earth, was an augury.

As soon as Earl Grebe had legal title to his land, he became an inviting target for Mervin Wendell’s real estate manipulations. The gracious, elderly man with the exquisite manners started to frequent Line Camp, making judicious but not secret inquiries about the Grebes: “Is a refined lady like Alice Grebe satisfied to live in a soddy?” “Mrs. Grebe seems the nervous sort. Maybe she’d like to sell the place and move to some town where life would be easier?” “Is this fellow Grebe adequate as a farmer? What I mean is, should he continue on the land or is he merely wasting his effort?”

So he watched for those times when Earl was plowing in the far corners; then he would stop by the soddy to ask Alice if she missed Ottumwa and whether she wouldn’t prefer to live in a place like Centennial, with real houses and where she could walk to the store.

“I like it here, and besides, it was you who encouraged us to take this land in the first place,” she said.

“But if you came to town, you wouldn’t have to live in a soddy.”

“Are many farmhouses you visit cleaner than this?”

“Oh, Mrs. Grebe! You misunderstand. I have the greatest respect for women like you. Backbone of the nation, I always say.”

Getting nowhere with her, he turned his attention to Earl, pointing out that if he cared to sell his half-section, there were houses in Centennial which he, Wendell, owned and which could be rented for a nice figure.

“Matter of fact,” Grebe replied, “what I’d like to do is homestead another half-section.”

“That might be possible,” Wendell said blandly.

“But I thought the law won’t allow it.”

“There could be ways,” Wendell said quietly as he drove off.

When it became obvious that the war in Europe would expand, and possibly involve the United States, the urge to break new land became irresistible. Even the weather cooperated, sixteen inches of rain in 1914, seventeen inches in 1915. Yield rose from a normal eighteen bushels an acre to a phenomenal thirty-one. As Ole Swenson had predicted, “If the war keeps on long enough, we’ll all be rich.”

For the Grebes such prosperity posed problems more perplexing than those of adversity. They now had money, but Alice wanted to spend it in building a real house; Earl wanted to buy more land. In this he was encouraged by Mervin Wendell, who now returned with the second half of his attack.

He drove up early one morning, smiling and affable, to congratulate Mrs. Grebe on the fine job she and her husband were doing. “You’ve made this place a little haven in the wilderness,” he said approvingly. “No wonder you wish to stay.”

“We aim to keep it neat,” she conceded.

“Where’s Earl?”

“Breaking new sod at the far end.”

“He’s a prudent man.” Picking his way carefully, Wendell started to cross the fields already plowed, but he had not gone far when Earl saw him and came down one of the long, straight rows he had turned earlier that day.

“Morning, Mr. Wendell. What brings you out?”

“Opportunity, Earl. It always strikes for a worthy man.”

Grebe could make no sense of this, but like the other farmers, he had grown accustomed to Wendell’s flamboyancies, and nodded. “What opportunity?” he asked.

“Right up there.”

Grebe looked in the direction indicated and saw nothing. Empty land stretched unimpeded in low sweeps and rises, none of it yet touched by the plow. It had once belonged to the Arlingtons, but like so many others, they had quit homesteading.

“It’s my land,” Wendell said. “A whole section. Young Arlington had his own 320. You know. ‘Do you swear by Almighty God that you are over age twenty-one?’ ‘I swear I am over twenty-one.’ ” He broke into a deep, reverberating laugh. “So right here, adjacent to your holding, we have 640 acres of the choicest drylands.”

“And you propose to sell it?”

“I do. In the hands of the right man, this land could produce thirty bushels.” Placing his right arm about Grebe’s shoulder, he indicated that he considered Grebe just the man to achieve it.

“How much?”

“You’re looking at five dollars an acre.”

“Too much.”

“It does sound high, Earl, but with wheat the way it is, this land can make your fortune. Talk it over with Alice.”

“It’s too much,” Grebe said flatly.