I SPENT THE MONTH OF OCTOBER 1973 SEARCHING CENTENNIAL for some man or woman whose life epitomized the history of the west. I wanted to send the US editors in New York a kind of capstone to our project, a detailed and intimate portrait of what westerners were doing and thinking about in these critical years prior to our national birthday celebration.

At first I focused on Centennial’s black barber, Nate Person, grandson of the only black cowboy ever to have ridden point on the Skimmerhorn Trail. The story of how this family achieved its position of love and leadership in my small western town was an American epic.

Then I shifted to Manolo Marquez, descendant of those redoubtable Mexicans, Tranquilino and Triunfador. He had a fascinating story to tell of breaking through prejudice and winning a solid place for himself. But these were special cases, and their association with Centennial began rather late in its history. I needed someone more deeply rooted in the community, and more typical. And then, on the last day of the month, I found my perfect prototype.

Early in the morning on November 1 I was breakfasting in a corner of the large room at Venneford Castle. Three moose heads, long undusted, stared down at me as I chatted with Paul Garrett, forty-six years old, tall and graying at the temples. He was one of the most perceptive men in Colorado, and a leader in many fields.

What attracted me to him especially was his combination of seriousness and self-deprecating good humor. For example, as I finished my tar-flavored cup of tea he told me, “My family has always favored that strange-smelling stuff. My grandmother, Pale Star … She was an Arapaho Indian you know … she said it tasted to her like charred jockstrap.”

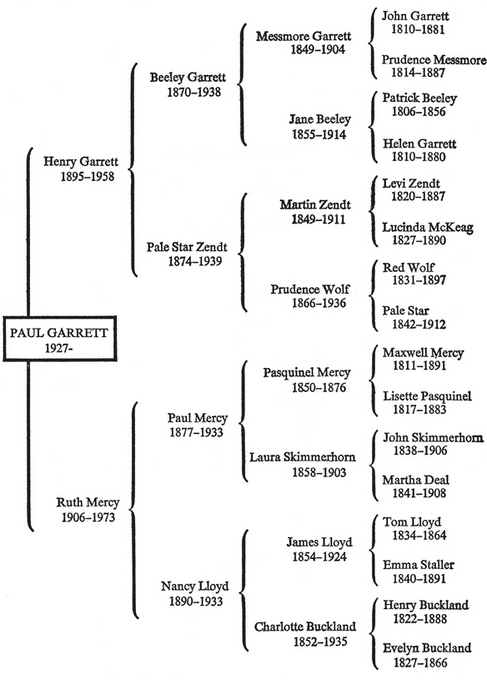

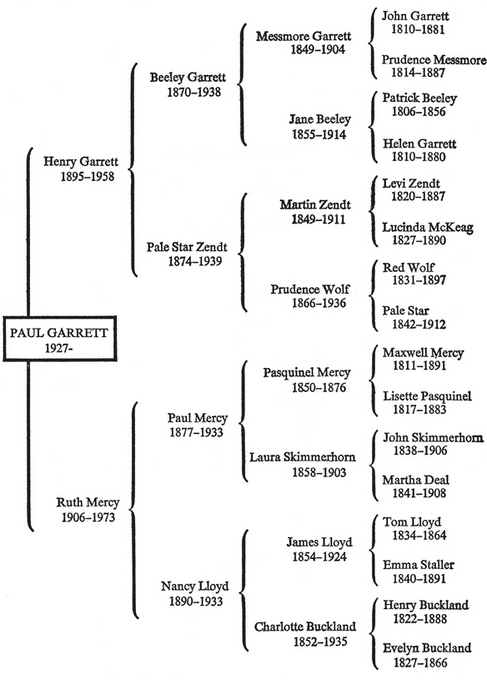

“Who were your grandparents?” I asked, and he produced from his cluttered desk a standard breed book in which he kept track of his prize Herefords.

“I’ve already studied the history of the Venneford bulls,” I told him, but he said, “Not this one,” and he opened the book to a page which he had filled out about himself, as if he were a Hereford. It showed his ancestors back to the fifth generation, and after I had studied it for a few minutes, I was confirmed in my earlier opinion that here was the man I needed to complete my report.

The Garretts had started in sheep, it is true, but they’d had the good sense to shift over to cattle. Paul had army people like the Mercys in his ancestry, and frontiersmen like Pasquinel. One branch of his family had been English, so he would know that interesting aspect of western development, and another branch was Indian.

“Garrett, Messmore and Buckland were of English stock,” he told me as I put the book down. “The Lloyds were a Welsh family that emigrated to Tennessee and Texas. Patrick Beeley was a hard-drinking Irishman. Pasquinel and Mercy were French, and writers usually ignore the French influence in western history. Zendt, Skimmerhorn, Staller and Bockweiss were Germans. Deal was Dutch, but originally he spelled his name a different way. Red Wolf and Pale Star were full-blooded Indians. Lucinda McKeag, whom everyone seemed to love, was the daughter of a squaw named Clay Basket, about whom the mountain men wrote in their diaries.”

“Pretty mixed up,” I said.

“Damned near incestuous,” he confessed. Then he slapped the breed book and said, “If you follow the history of the really great bulls, you’ll find many instances of very close in-breeding. My case, the same way. A son of Lucinda McKeag married the daughter of her brother. Messmore Garrett married his first cousin. And Henry Buckland, father of the formidable Charlotte you’ve spoken about so often, married his niece, if you please.”

Before I could respond to this last bit of information, the telephone rang and an elderly Mexican serving woman shuffled in to report, “It’s very important.” And she handed him the phone from his desk.

It was the new governor of Colorado, eager to share some exciting news: “At my ten o’clock press conference this morning I’m announcing your appointment as head of our executive committee responsible for the state centennial celebration.” This was a greater honor than a stranger might have appreciated, because Colorado alone of the fifty states would be celebrating in 1976 not only the two-hundredth birthday of our nation but also the hundredth anniversary of the state.

“This fits in perfectly,” I said when I heard the news. “What I’d like to do, Mr. Garrett, is to follow you around a bit. For a couple of weeks. Listen in as you conduct your business … give my editors a feeling for what a westerner is doing these days. If you wouldn’t mind, I wish you’d carry this tape recorder with you when I’m not there. Just in case there’s something you’d like to get off your chest.”

“A month ago I’d have said no,” he replied. “It isn’t easy, Vernor, when your wife dies. Not even when you haven’t been really married, which was my case, as you may have heard.”

“I’ve heard a good deal about you,” I said. “I’d like to know more.”

“If the tape recorder works, you may know a helluva lot more.” He insisted on my staying for lunch, and as we ate beneath the moose heads, word of his appointment penetrated to various corners of the state, and his phone began jangling, with citizens from the western slope of the Rockies demanding to know if they were to form part of the twin celebrations, or if they were as usual to play second fiddle to the greater concentrations of population along the front range. “Of course you’re counted in,” he assured them. “First thing I do tomorrow is drive across the mountains to consult with you. Get your crowd together. Decide what you want, and I’ll have dinner with you tomorrow night … in Cortez.”

On November 2 he got me out of bed early, filled his gray Buick at the ranch gasoline pump and headed for the mountains. There had been rumors that gas rationing might be imposed, and perhaps a speed limit of fifty miles an hour. “Impossible speed for the west,” he muttered as he settled the car into its normal cruising speed of eighty. By the route we had planned, the day’s drive would cover some six hundred miles, but with the excellent roads that crisscrossed Colorado, this was a short trip for a western driver. Cutting onto the interstate west of Venneford, we roared south toward Denver, skirted that city and headed into the high passes at ninety miles an hour.

We had gone only a short distance when Garrett saw something which had always pleased him. It demonstrated the imaginative manner in which Colorado had confronted some of its problems, for in the building of the interstate the engineers had to cut through a tilted geologic formation, and instead of simply bulldozing a path through the little mountain, they had made an extremely neat cut which exposed some twenty geological strata. A park had been built around the multicolored edges, so that schoolchildren could wander across the steep slopes of the cuts and actually touch rocks which had formed two hundred million years ago. They could inspect the purple Morrison formation in which the dinosaurs had been found, and could see how layers of sea deposit had been thrust upward when the Rocky Mountains erupted. “This is one of the best things accomplished in Colorado in the past twenty years,” Garrett told visitors, “and it cost practically nothing. Just some imagination.”

He loved driving, for he responded to the motion of the car as it leaned gracefully into the well-banked curves. There was a kinesthetic beauty about pushing a quietly running automobile through the mountains, and it helped him sense the quality of the land he was traversing. Looking above him as he sped along, he saw once more the noble peaks of Colorado. Often he had astonished eastern visitors by asking, “You’ve surely heard of Pikes Peak. How many mountains in Colorado are higher? Give a guess.”

Many easterners had never heard of Colorado’s other mountains, and they were always surprised when he told them, “We have fifty-three mountains higher than fourteen thousand feet—many, many more than any other state. Pikes Peak is a mere hill. It’s number thirty-seven on the list—only 14,111 feet high.” Even Longs Peak, which his family had always called Beaver Mountain, was no more than fifteenth on the list. This was truly a majestic state.

He kept his foot well down on the throttle as we roared toward Eisenhower Tunnel, highest major tunnel in the world; it would take us deep beneath the Continental Divide and at its western end bring us into some of the loveliest valleys on earth. Here new ski centers were being developed, and he stopped briefly at several to alert the proprietors that he expected them to contribute some topnotch sports events for the celebration.

At Vail, where we halted for midmorning coffee, sixteen local leaders met with him, showing him the imaginative plans they had developed for the centennial. He liked the people of Vail and was impressed with their energy. Some years ago the ecologists had feared that the proliferation of ski resorts might ruin the mountains, but he had supported the ski runs, for he saw mountains as places for recreation, a locale in which city people could escape their pressures, and he had been right. A properly planned ski resort did not scar the landscape; it made the rewards of nature available to more citizens—but only if enough primitive area was held inviolate. Whenever the Vail plans threatened the wilderness, Garrett would have to oppose them.

“If you want new runs along the highway, I’ll support you,” he promised. “But on your plans to commercialize the back valleys, I’ve got to oppose you.”

Since he had championed the resort in previous applications, the Vail people accepted his veto, and as we left he assured them, “We’ve got no budget yet, but when we get one, I’ll allocate funds for planning. You’re on the right track.”

We now doubled back to Fairplay, a beautiful village surrounded by mountain peaks, and there Garrett encouraged the leaders to come up with their own ideas. Then we crossed a series of trivial bridges which always pleased him, for under them ran those minute rivulets which formed the headwaters of the Platte. Here, high in the Rockies, these clear, sweet streams ran through alpine meadows; it seemed impossible that they could coalesce to form the muddy serpent that crawled across the plains.

Then came one of the most enjoyable parts of the drive, a long leg south through those exquisite valleys that so few travelers ever saw, with giant mountains on both sides and the road pencil-straight for fifty miles at a time. He drove at ninety-five and felt his heart expanding as the Sangre de Cristo Range opened up before us to the east. He had known Tranquilino Marquez before the old man died and had once heard him tell of the impression this desert road had made on him when he first came north from Old Mexico to work in the Centennial beet fields. “It was like the finger of God drawing a path into the mountains,” the old man had said.

At the end of the valley we turned west and soon found ourselves driving along a river not often recognized as a Colorado stream. It was the Rio Grande, tumbling and leaping as it dropped out of the mountains, and as he watched its whirlpools he reflected on the crucial role his state played in providing water for the nation. Four notable rivers had their birth in the Colorado uplands—Platte, Arkansas, Rio Grande, Colorado—and what happened there determined life in neighboring states like Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, New Mexico, Arkansas, California, and even Old Mexico. Colorado was indeed the mother of rivers.

Now Garrett flicked on an invention which in recent years had given him much delight, a cassette player built into the Buick, one into which the driver inserted a small plastic cassette containing ninety minutes of music recorded on tape. Two speakers at the rear of the car provided a stereophonic effect, and as the car headed west for the Spanish country, the cassette poured forth a flood of luscious sound. The sensation of driving ninety-five miles an hour over flawless roads, with towering mountains watching over you while music reverberated through the car, was a sensuous joy.

Today, and for some time past, Garrett played only Chicano songs. Some years ago he had formed the habit of taking his lunch, when in Centennial, at Flor de Méjico, the restaurant owned by Manolo Marquez, and there he had grown acquainted with the flamboyant folk music brought north by the Chicano beet workers, and the more of it he heard, the more he loved the rowdy, rambunctious rhythms. Now “La Negra” echoed through the speeding car, a saucy, tricky beat. After that came “La Bamba,” in which a girl singer with a provocative voice shouted, “Soy capitán, soy capitán, soy capitán.” That was followed by “Little Jesus from Chihuahua,” which he had grown to like very much, but then came the finer songs, the ones that caused him involuntarily to slow down.

“Las Mañanitas,” the birthday song with that totally strange beginning “This is the song King David sang,” captivated him, and he always sang along. “It must be the strangest birthday song in the world,” he told me, “and the best.”

As for “La Paloma” and “La Golondrina,” they were songs of such ancient beauty that he wondered if any country had ever produced such appropriate popular music to summarize its contradictory longings: “If a dove should fly to your window, treat it with charity, for it is really me.” No self-respecting American would dare write words like that, nor elect them as a national symbol if he did.

Now the Buick was crawling along at forty-five, toward Wolf Creek Pass, for the tape had come to that strange song which had possessed him in recent months. No other person he had spoken to in the Anglo community had ever heard of it, and only a few Chicanos knew it. “Dos Arbolitos” it was called, and he had it in two versions. The first, which now drifted dreamily from the speakers, was played by an orchestra of forty violins and a few wind instruments; it was quite unlike usual Chicano music, for although it bespoke a deep passion, it also had a sweet gentleness. The melody was simple, with delightful rising and falling notes and unexpected twists. It was the song which first awakened him to the fact that Chicano music was something other than “La Cucaracha” and “Rancho Grande.”

It was this song that had lured him on his first trip to Mexico, when he had driven those desolate miles to Chihuahua and those flower-strewn miles farther south. Places like Oaxaca had been a revelation to him, and he had come home with two records of “Dos Arbolitos,” one the stringed version which he had just played and another in which two voices, male and female, sang the sentimental words:

“Two little trees grow in my garden,

Two little trees that seem like twins.”

The Buick had dropped to a mere forty while Garrett joined the singers, tilting his head back and barely watching the road. When the song ended, he leaned forward and reversed the tape until he felt it had returned to the starting point of the violin version, then released it to play again. Once more “Dos Arbolitos” sounded, and he sang with the violins.

We had a very late lunch at Pagosa Springs at the western end of Wolf Creek Pass, where he met his first delegation of Spanish-speaking citizens. He told them he wished he could address them in their own language, but whereas he understood Spanish when they spoke it, his attempts to respond were laughable.

“Let us laugh,” one of the Chicano leaders suggested, so he said a few words. “It’s pretty bad,” the Chicano agreed.

He told them that in the forthcoming celebrations there would be an honored place for Chicanos. “We’ve heard that before,” they said with some bitterness.

Montezuma and Archuleta had recently started a mock-serious separatist movement, seeking to join New Mexico, since distant Denver never gave a damn for their interests. “That’s all changed,” Garrett assured them. “The governor himself wanted me to come down here to tell you of our plans.”

“Him, yes,” the Chicanos said. “But what about his successor?”

“Those of us on the front range have learned our lesson. We know you exist.”

He made little impression on the suspicious men of Pagosa Springs, so late in the afternoon we headed for Durango, pausing there briefly before continuing to our final destination, Cortez, not far from that historic spot where four states meet, the only place in America where that happens. In Cortez we had a late dinner with leaders of the Chicano minority and talked with them late into the night.

On November 4, which was a Sunday, we made several extended tours with the Anglos of Cortez, and they showed us their plans for a ceremony at Four Corners, a bleak point in the desert but a place with considerable emotional appeal. “I can imagine lots of Americans wanting to drive this way,” Garrett said, “if we have something to offer them when they get here.”

On November 5 we headed back to Centennial by the northern route, and once more we roared along the spacious highways while Chicano music thundered from the cassettes. Again Garrett slowed down when it came time to sing along with “Dos Arbolitos,” but after a while he turned off the machine, and during the long haul from Grand Junction to Glenwood Springs he discussed the difficult problem he would face the next day.

It was election day and Colorado would be the first state in the nation to face up to the future, for it was electing an officer of a new description. His title was resounding, Commissioner of Resources and Priorities, and his task was to steer the state in making right industrial and ecological choices. It was appropriate that Colorado should be the state to experiment with such a concept, for its citizens had always been pioneer types, willing to sponsor change. Colorado had led the nation in old-age pensions, proper funding of education, liberal labor laws, and it had been the state which turned down the 1976 Winter Olympics as destructive to the environment.

When one looked at the original settlers, men like Lame Beaver of the Arapaho, Levi Zendt of Pennsylvania, Potato Brumbaugh from Russia and Charlotte Buckland from England, it was no wonder that traditions of individualism had been established. Now the state would lead the nation in trying to define an acceptable use of its resources.

The new officer had already been dubbed the Czar, and tomorrow the first man to occupy the crucial office would be elected. Like most Coloradans, Garrett felt that the Republican party represented the time-honored values of American life and could be trusted to place in office men and women of probity who would remain above temptation. Whenever a Republican officeholder turned out to be a crook, as one or another did year after year, he explained away the affair as an accident.

On the other hand, he felt that in time of crisis, when real brains were needed to salvage the nation, it was best to place Democrats in office, since they usually showed more imagination. And when one Democrat after another proved colossally stupid, he termed that failure an accident too.

He was always willing to split his ticket, not wishing to be like the old beet farmer at Centennial who said, “Me! I vote for the man not the party. Harding, Coolidge, Hoover, Landon, Willkie, Dewey, Eisenhower, Nixon, Goldwater.” For example, Garrett had voted for both John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, but looking back, suspected that he had made a mistake each time.

The preceding night, while we were watching television in his motel room, he found his politics becoming confused. Julie Nixon Eisenhower was shown defending her father. “Fight, fight, fight. My father will never resign,” the attractive young lady proclaimed, and Garrett judged it to be improper for a father to use his daughter in such an undignified way. “If he wants to defend himself,” he had growled at the television, “let him do it himself … not hide behind his daughter’s skirts.” He had voted for Nixon, had met him twice in Denver and had liked him, but now he told me, “I’m beginning to wonder if the man can ever extricate himself from the morass he’s fallen into.”

He found himself equally bewildered when he considered his choice on Tuesday. The Democrats had nominated for commissioner a lackluster man from the western slope, and it would be fairly easy to vote against him, except that the Republicans had chosen a man from Centennial, and to Garrett he was simply unacceptable.

The candidate was Morgan Wendell, born the same year as Garrett and a graduate in the same class from the University of Colorado. He was a wealthy man, his father having made a killing in wheat during World War II, and in business relations he was quite reliable. He had done well in college and had served the state in various capacities. It looked as if he would win handily, so that whether Paul Garrett voted for him or against him was of little moment.

But Garrett prized his vote. It seemed to him the noblest ritual of American life, and he had never failed to vote, nor had he voted carelessly.

The Buick slowed perceptibly as he asked himself, What is it about Morgan Wendell I don’t trust? He put aside the secret gossip which had circulated within the Garrett family. Paul Garrett’s grandfather, Beeley Garrett, had told the family, with Paul listening, that a Mr. Gribben, before he died, had confided that Maude and Mervin Wendell had stolen their first house from him by working the badger game.

“What’s the badger game?” Paul had asked.

“It’s when a man gets caught with his pants down in somebody else’s bedroom and is afraid to admit it.” Grandfather Garrett had continued with the part of the story that worried Paul: “We had a Swede come to town about that time, man named Sorenson, and he disappeared. A lot of his money was missing. Something that Sheriff Dumire told me at the time made me think that he suspected the Wendells of having done away with the man. I know for a fact that Dumire was on to something, but before he could settle it he was killed in a street fight.”

That was rumor, and Paul dismissed it as something that had happened more than eighty years ago. What possible difference did it make now? But the next charge was not rumor, and it was a harsh one. Paul’s own father related the details when Paul was twelve years old.

It was on the first day of World War II, back in 1939, and the Garretts were having their usual early breakfast when the phone rang. It was Philip Wendell, the real estate man, and he had called to inform Paul’s father that a deal they agreed upon—Henry Garrett would buy back four thousand acres which had once belonged to Crown Vee—was called off.

“But we shook hands on that deal, Philip,” Henry Garrett said. There was a brief silence, and then he said, “Of course. There’s nothing signed. You never brought me the paper. But doesn’t your word mean anything?” Another silence, followed by Henry Garrett’s shouting, “You miserable son-of-a-bitch!” after which he slammed down the phone.

Returning to the breakfast table, he trembled for some moments, then turned to Paul, saying, “Never in your life have anything to do with a Wendell. He went back on his word.”

“What does that mean?” Paul had asked.

“He shook hands with me, promised to go through with a deal at a price agreed upon. Something’s happened whereby he can make a little more money, so he refuses to honor our agreement.”

“What could it be?” Paul’s mother asked, but her husband ignored the question, and she left the room. Turning to his son, he shook hands formally and said solemnly, “If you shake hands on anything, Paul, and then break your word, I do not care ever to see you again. The association of men is founded on honor, and no Wendell has ever understood that basic truth.”

“Henry,” his wife called. “Listen to what the radio’s saying!” And when the fact of war was known, Philip Wendell’s revoking of his promise was understood. “If he plants all that land in wheat,” Ruth Garrett said, “he’ll be very wealthy … if the war continues.”

“Let him have it,” her husband said with smoldering fury. “Paul, never earn money that way. It’s not worth it.”

From that time Paul Garrett had watched the Wendells with deepening interest, and he concluded that his father was right. The Wendells, none of them, had any basic sense of responsibility. At the university Morgan Wendell had done everything to ingratiate himself with older men in power—professors, athletic coaches, fraternity leaders, he had toadied to them all—but no one ever knew what principles he stood for, and on this program he prospered.

And in his adult life he had continued to prosper. Now he stood on the threshold of becoming an important official of a great state, and perhaps Paul Garrett was being overly cautious in wondering if he could vote for such a man. As we drove eastward toward the Eisenhower Tunnel he grabbed the tape recorder and started dictating, as if determined that I have an exact account of what he was disclosing:

I don’t trust him, Vernor. It’s as simple as that. It’s not the things his grandparents did … and I haven’t told you that whole story because it really doesn’t concern you. And it’s not because his father was a sneaky operator, because I don’t believe the sins of the father are visited on the heads of the sons. It’s just that he’s a low-grade individual without principle. He’s a technician. He can perform. He can keep things from getting tangled. But in a crisis he’ll have no base from which to operate. He believes in nothing. At the university he took no classes that made him think. He’s never stretched his mind, because he’s never faced himself … or the facts … or the future. And I think democracy can’t function unless it’s led by men and women who know what kind of people they are. How can you solve an equation if x is never known?

When we reached the interstate leading back to Greeley he drove at a hundred and five, telling me, “Tomorrow I’ll get up at dawn and figure this thing out. I’ll saddle Bonnet and ride over to look at the Herefords.”

On Tuesday, November 6, Garrett did not get to the polls till late, because when he returned to the castle following his long ride, he was deeply agitated. For some time he sat alone, his head in his hands, pondering not the election, for on that his mind was fairly made up, but the painful confrontation he faced regarding his beloved Herefords. When he had seen those stalwart beasts in their distant pastures and watched as they moved slowly toward him, white faces shining against red coats, he felt a knife-thrust of pain as he recalled the vicissitudes he and his family had brought upon this noble breed. The Garretts had always acted in good faith where the Herefords were concerned. Great-Grandfather Jim Lloyd had loved them almost as dearly as he had loved his own daughter, and the ranch had always bought the top bulls, but somewhere things had got onto the wrong track, and now they must be corrected.

“I’d rather cut off my right hand,” Garrett said, and he meant it. He was about to make a phone call to Montana when he heard footsteps on the porch, and when he went out he found to his astonishment that Morgan Wendell, the presumptive Czar, was standing there.

“I had to vote early,” Morgan explained. His manager had told him, “Be there at seven. I’ll have photographers on hand, and we’ll make all the afternoon papers.” He had stood by the voting machine with his wife, both of them smiling.

“I trust you’re going to vote, Paul.”

“Never miss.”

“Isn’t this rather late to be campaigning?”

“I’m not campaigning. It looks as if I’ll win safely, and I don’t give a damn how you vote.”

Garrett had made no move to invite Wendell into the castle, a place the real estate man had rarely visited, but this sharp rejoinder brought him to attention. “What’s the reason for the visit, Morgan?”

“Something very important, Paul.” The candidate hesitated, and Garrett said, “Come on in,” and Wendell said, “Thanks.”

As Garrett ushered him into the big room with the moose heads, Wendell said abruptly, “Paul, you and I have never gotten along well, and I suppose that when you do vote, you’ll vote for Hendrickson.” Garrett shrugged his shoulders but said nothing. “What I’m here for is to tell you that I need your help … need it badly.”

“You just said you didn’t give a damn.”

“On the voting … who cares? But on the morning after I’m elected—and I think I will be—I’m going to require some first-rate brains to help me out. No, don’t interrupt. Brains are not my long suit. But sensing what’s happening in the world is—anticipating what troubles people.”

“How does this involve me?”

“Most directly. The great problem in the next decade in Colorado will be to save the state. I really mean that. To save the forests, the trout, the elk—and especially things like the rivers and the air we breathe.”

Paul Garrett leaned back and studied his visitor. “You know, Morgan, for the first time in your life you’re talking sense.”

“I’ve learned it from men like you,” Wendell said. “The first appointment I want to give to the press is my deputy, Paul Garrett.”

“It’s a job I’d have to accept … if offered.”

“I knew you’d say that.”

“But, Morgan, I won’t take it just to provide a façade for you. When you speak about ecology it’s the popular word, the in-thing to do politically. And I have no objections, because men have to get elected. But when I use the word it summarizes my whole life. I may not be an easy man to live with.”

“That I understand,” Wendell said. “Let’s leave it this way. You make every decision about our natural resources just as you see it, and when you become totally intolerable, I’ll fire you with a ‘Dear Paul’ letter and replace you with someone a little more congenial. I judge we can tolerate each other for at least three years, and in that time the basic task can be started.”

“Sounds workable,” Garrett said. Then he thought of something that might prove disqualifying. “You know, Morgan, that I’m testifying at the Calendar trial this week. It could prove sticky.”

Wendell lowered his head, for this was unpleasant news. The Calendar trial was bound to agitate voters across the state, and to have his deputy take sides was bound to be unsettling. “Couldn’t you duck that one, Paul?”

Garrett laughed. “You see, even before you make the appointment you’re asking me to draw back. Morgan, the Calendar trial is at the heart of all we’ve been talking about. Of course I can’t duck it. Of course I’m going to embarrass you.”

“Maybe I could delay announcing your appointment. That would be reasonable.”

“Anything is reasonable,” Garrett said. “Anything on God’s earth can be given a reason. But if you delay, I won’t accept the appointment. Can’t you see, Morgan, I will always be a thorn in your side, because the protection of this state will invariably irritate people whom you want to placate … whom you must placate. It’s going to be a dogfight every inch of the way. We know that. Question is, can we live with it?”

Wendell contemplated this forthright declaration of difference, then said, “Your job will be to protect all the natural good things of this state, and I know you’ll do it. My job is to see that industry gets a fair shake so there will be jobs and tax rolls. You conserve the water. I want every drop I can get for new cities and new factories. It will be difficult, and you want to make it worse by getting mixed up in the Calendar affair … infuriate every hunter in the state.”

“You wouldn’t want me, Morgan, if I weren’t committed on such issues.”

Morgan Wendell, facing the first difficult decision of his future administration, took a deep breath and said something which took Garrett completely off guard. “Paul, do you know who my favorite American of all time was? Warren Gamaliel Harding. Because he came along at a lush period of our national life, when we had a comfortable margin for error. And he proved how horrible an elected official can be. He’s a warning for all politicians. On the day we take office we all think of President Harding and we say to ourselves, ‘Well, I won’t allow myself to be as bad as that.’ Harding keeps the ball game honest, and I judge him to be one of the most useful Americans who ever lived. I’m not going to be the Colorado Harding.”

“I’m having lunch in town,” Garrett said. “At the Marquez place. Join me.”

So the first public appearance the Czar made was in the Flor de Méjico, with a man who was known to be cool toward his candidacy. It did Wendell a lot of good in the district, but shrewd politician that he was, he saw something that day which would aid him even more. He had an unusual gift for sensing what was going on in his vicinity, and as he entered the restaurant with Garrett he noticed that Paul hesitated in the doorway and looked in all directions, then walked to the table, plainly showing his disappointment.

Later in the meal Wendell was watching Garrett out of the corner of his eye and saw his future deputy’s face brighten. Looking toward the kitchen, Wendell saw Manolo Marquez’s daughter come in with an armful of dishes. Townspeople knew that she had been married in Los Angeles, but after only two weeks, she had returned home with a scar down the side of her face and grounds for divorce. Well, I’ll be damned! he said to himself. Old blue-blood Garrett and a Chicano girl! That could make me very popular with the Chicano voters in the southwest. I will be damned.

That afternoon when Paul Garrett went into the secrecy of the polling booth and looked at the two names confronting him—Charles Hendrickson, a man who lacked every qualification that Democrats sometimes had, and Morgan Wendell, a man without the basic character expected in Republicans, he felt a great nausea. I’ll be damned if I can vote for either of them, he decided, and after pulling the lever for one of the Takemoto boys who was running for school board and another lever for a German woman, he left the booth without voting for Czar on either ticket.

On the following day he began his series of inspection tours, those brief trips during which he simply looked at the land he would be protecting. His journeys east through the drylands sometimes brought tears to his eyes as he surveyed that chronicle of lost hope, but he was even more deeply distressed by what he saw along the front range from Cheyenne down to the New Mexico border:

When I was a boy we had an old book, Journey West by John Brent of Illinois. He came this way in 1848, and I remember his writing in his diary that one morning, while they were still one hundred and five miles east of the Rockies, they could see the mountains so clearly they could almost spot the valleys. Look at them now! We’re ten miles away and we can’t see a damned thing—only that lens of filth, that curtain of perpetual smog. What must be in the minds of men that they are satisfied to smother a whole range of mountains in their aerial garbage? This must be the saddest sight in America.

South from Cheyenne, clear across Colorado, hung a perpetual veil of suspended contamination. The lens appeared to be seven hundred feet thick, composed of industrial waste, especially from the automobile. Week after week it hung there, stagnant. Had it clung to the ground, it would have imperiled human breathing and would have been treated as the menace it was, but since it stayed aloft, it merely blotted out the sun and dropped enough acid to make the eyes smart twenty-four hours a day.

From Centennial, Beaver Mountain was no longer visible, and whole days would pass with the cowboys at Venneford unable to see that majestic range which once had formed their western backdrop. Men who used to stand at the intersection of Mountain and Prairie, inspecting the Rockies to determine the weather, now had to get that information from the radio.

Garrett was especially perturbed about what had happened to Denver, once America’s most spectacular capital, a mile-high city with the noblest Rockies looking down on the lively town, made prosperous by the mountains’ yield of silver and gold. Now it was a smog-bound trap with one of the worst atmospheres in the nation, and the mountains were seen no more.

There were days, of course, when the contamination was swept aloft by some intruding breeze, making the peaks visible again for a few hours. Then people would stare lovingly at the great mountains and tell their children, “It used to be this way all the time.”

During the past ten years Paul Garrett had often had the dismal feeling that no one in Denver gave a damn. The state had succumbed to the automobile, and any attempt to discipline it had seemed futile. Year after year, two citizens a day were killed by cars throughout the state, and no one did anything to halt the slaughter. Drunk drivers accounted for more than half these deaths, but the legislature refused to punish them. It was held that any red-blooded man in the west was entitled to his car and his gun, and what he did with either was no one else’s business.

The west had surrendered to the automobile in a way it had once refused to surrender to the Indian, for the car in one year killed more settlers than the redman did during the entire history of the territory. The concrete ribbons ate up the landscape and penetrated to the most secret places. And if by chance some valley remained inviolate, the snowmobile whined and sputtered its way in, chasing the elk until they died of exhaustion. No place was sacred, no place was quiet, in no valley was the snow left undisturbed.

Paul Garrett, pondering these problems in the early days of November, made a series of promises: “As Deputy Commissioner of Resources and Priorities I’m going to switch to a small car. I’m going to drive slower. Day and night I’m going to tackle the Denver smog. And I’m going to ban snowmobiles in every state forest.” Even so he feared that such measures might be too late, and he muttered sardonically, “Pretty soon, if you want to see the unspoiled grandeur of Colorado you’ll have to go to Wyoming.”

On Friday, November 9, Paul Garrett faced up to a most disagreeable task. He shaved carefully, dressed in a conservative business suit, and with his razor, trimmed some of the gray hair about his ears. This would be his first public appearance since the announcement of his appointment to the new position, and he wanted to make a good impression.

He drove to the Federal Court in Denver, where the trial of Floyd Calendar was to start. The judge was a small, alert man with a well-known sense of humor, and the contesting attorneys were men who typified the forces at stake in this case. The district attorney, representing the conservation forces of the nation, was a former athlete who could not in the slightest degree be termed a bleeding heart, while the defense attorney was a famous outdoors man, well known as a hunter and a rancher.

The accused was something else again. Floyd Calendar was a mean-looking, thin, heavily bearded man in his early sixties. He wore no tie and his suit seemed several sizes too large, even though he was a tall man. He had one tooth missing in front, which made his normally surly countenance almost sinister. Even so, he represented hunters, men who loved the outdoors and ranchers who sought to protect their livestock.

Calendar was involved in two serious crimes: shooting bald eagles, our national bird, from a plane and killing bears, an endangered species, in “a cruel and unfair manner.”

The first prosecution witness was Harold Emig, from Centennial. The government lawyer wanted to use him to establish the kind of man Floyd Calendar was.

“He was a guide,” Emig said. “First public job he had was putting parties together to shoot prairie dogs.”

“Are prairie dogs edible?” the prosecutor asked.

“Oh, no! You just shoot prairie dogs for the fun of it. Floyd knew where all the dog towns were. There aren’t many these days, you know. And for a dollar a head he would take us out there, and we’d rim the prairie-dog town. We’d be on the west, you understand, so’s the sun would be in the critters’ eyes, and Floyd had drums and whistles and he knew how to make the little fellows stick their heads up, and when one did we’d blaze away.”

“How many dogs would you kill?”

“Well, on a good day when Floyd’s whistles were working, each man would get maybe ten, twenty … that’s not countin’ probables.”

“What did you do with them?”

“Nothin’. A prairie dog ain’t good for nothin’. You couldn’t eat ’em. It was just the fun of seein’ a little head pop up from the hole and blasting it with a well-aimed shot.”

“Does Mr. Calendar still conduct such hunts?”

“No, sir. After a while the dogs were pretty well cleaned out, and he turned to rabbit drives. You get sixty, seventy men with clubs and you range over a pretty large area, always closin’ the circle, and in the end you have an excitin’ time, everybody clubbin’ rabbits to death.”

“I thought that was stopped some years ago.”

“Yeah. Life magazine slipped a photographer into one of Floyd’s hunts and took pictures of the men … I was in the middle of one of the shots. Well, it sort of irritated a lot of women back east … grown men you know, clubbin’ jackrabbits that way, but they never seen what damage a rabbit could do.”

“Then what did Mr. Calendar do?”

“Well, he came up with a real fine idea. Lot of men in pickup trucks and special huntin’ dogs, and we’d go out onto the prairie, far away from everything, and we’d turn up some coyotes, and we’d chase after ’em for mebbe ten miles and then we’d let the dogs go and they’d zero in on a coyote.”

“Then what?”

“Then the dogs would tear him apart.” There was a pause in court, and Emig added, “It was necessary, of course, because coyotes eat sheep.”

“Your sheep?”

“No.”

“Mr. Calendar’s sheep?”

“No. We just went along for the fun.”

The prosecution now called a new witness, Clyde Devlin, a dynamiter. “What we done, there wasn’t no more prairie dogs, and the coyotes was used up, so Floyd, he kept lookin’ for anything sportin’, and his mind fell on the rattlers up at the buttes. We bought small sticks of dynamite and threw them into the dens. Killed a lot that way, but the fun was standin’ around with shotguns and blastin’ the others as they crawled out.

“But the reason people was willin’ to pay money for the dynamitin’ was the fun of seein’ Floyd handle rattlers. He had a way of pinnin’ ’em down with a forked stick, then pickin’ ’em up by the tail and snappin’ ’em like a whip. The rattler’s head would fly off. I seen him whip sixteen snakes in one day, and nobody else had the guts to try even one. Me? I wouldn’t get near ’em.”

The prosecutor turned to the first serious charge. Calling to the stand Hank Garvey, pilot of a small plane stationed at Fort Collins, he asked, “When, in your opinion, Mr. Garvey, did Mr. Calendar first direct his attention to eagles?”

“We were flyin’ one day, about five years ago, and in the distance we seen this eagle come off a dead tree, and we both watched it flyin’ for some time, and Floyd said, ‘Hell, Hank, with the right attention a man could stay on that eagle’s tail and blast him right out of the sky.’ So we spent a whole week makin’ dry runs, seein’ if we could spot eagles and close in on them, and we found it was right easy. Eagles don’t fly half as fast as they show ’em in the cartoons.”

“When did the idea … I mean, whose idea was it to do this commercially?”

“That came natural. Floyd and I knew a lot about hunters, him bein’ a guide and all, and we knew how tough it was for a hunter to bag hisself a eagle. Some very good shots tried for years without ever gettin’ close to one, let alone hittin’ it. And this bugged ’em, because on their walls they would have the head of a rhinoceros from Africa and a tiger from India, but they wouldn’t have their own national bird. There was a blank spot on their wall, and they were hungry to do somethin’ about it, because nothin’ looks better, when it’s mounted right, than a bald eagle.”

“When did the commercial aspect begin? Your first customer, that is?”

“One day when we were practicin’ on dry runs we came so close to a big bird that Floyd cried, ‘Shit, a man don’t even have to aim. If he can point a gun he can get hisself a eagle this way.’ So there was this dude from Boston. Had one of everything in his game room except a eagle. Even had a Kodiak bear, and wanted a eagle so bad he could taste it.

“He told Floyd before takeoff, ‘I don’t think you can get a eagle this way, but if you bring me onto one, I’ll give you five hundred dollars.’ Then he turned to me and said, ‘And there’ll be a little somethin’ in it for you.’ So we were bound to locate a eagle.”

“Did you?”

“We cruised for a while west of Fort Collins and didn’t find nothin’. So we sorta drifted down over Rocky Mountain National Park, where we turned up a big, beautiful bird. The dude wanted to fire as soon as we saw it, but we didn’t want to shoot him over the park, because we might run into trouble when we landed to pick it up.

“So I swung the plane south of him and we worked him north, out of the park, and when he was over plowed land I moved in real close.

“Now, the eagle and the plane fly at about the same speed, so it was just like the bird was standin’ still. And that’s where we made our big mistake on our first try. I got too close. Hell, you could of killed that eagle with a broom.

“So when the dude does fire he practically disintegrates the eagle. We spent the better part of a hour pickin’ up the various bits and pieces, and when we hauled them in to Gundeweisser, the taxidermist, he looks at the pile and asks, ‘How do you want this job made up? As a duck or a eagle? I can play it either way.’

“He turned out a masterpiece. Spread-eagled, talons projectin’, glass eyes flashin’. The dude was delighted and sent us the picture you have over there. When we showed it to Gundeweisser, he said, ‘That eagle’s two-thirds plastic, but he’ll never know.’ So after that I kept the crate a little farther away so’s the gun blast didn’t tear the bird apart.”

“How many did you kill from your platform in the sky?”

“Somethin’ over four hundred, but me’n Floyd never shot a single one. Always some sportsman who wanted our national bird on his wall.”

Taxidermist Gundeweisser confirmed these figures. “The boys brought me their eagles because I’d perfected the knack of making them look extra ferocious—talons extended. I was able to do this because I bought only first-class eyes from Germany—hard glass with a flash of yellow. I mounted over four hundred eagles, and nobody ever wanted the bird just looking natural. Always had to be in the act of killing something, talons extended.”

One of the state naturalists was now called, and he testified that he and his associates had been watching Floyd Calendar for some time. “National publicity on the eagle thing scared him off that line, and we never saw the plane again. What he directed his attention to was bears. There was almost as good a market for bears as there was for eagles, and he devised a sure-fire way of helping an eastern hunter bag his bear.”

“Explain it, if you will.”

“He learned to trap bears. He probably knows more about bears than any man in America. At the beginning of each season he’d trap eight or ten beauties and hide them in cages deep in the woods. When some sportsman came along Floyd would charge him one hundred dollars for the hunt, two hundred if he bagged a bear. He would take the sportsman to one of several cabins in the woods, and about a quarter of a mile away he would have one of his bears in a cage. At five in the morning he’d sneak out and let the bear loose and at five-fifteen he and the sportsman would start trailing it, and by five-thirty the bear would be dead. I investigated three dozen cases like this, and never did the hunter suspect what Floyd had done. He handed over two hundred dollars and was delighted with the deal.”

“Then what happened?”

“Well, every now and then Floyd would release a bear that would take off in some unanticipated direction, and there’d be no chance of trailing him. So he adopted the practice of not feeding the caged bears for two weeks prior to releasing them. Now there were few escapes, because the bear would stop to eat, and the sportsman could creep up and gun it down.”

“We’d like to hear what Mr. Calendar tried next.”

“Ranger Quarry will explain that.”

A very young man took the stand, with a collection of gadgets to which the clerk gave numbers. “Mr. Calendar was still not satisfied, for an occasional bear would still get away. We have evidence that his new plan was inspired by an article in National Geographic in which I detailed experiments I had made in Canada on the hibernating habits of bears. In the article, which now I’m sorry I wrote, I explained how we attached to the bear a very small radio device, like this. Wherever the bear went, it sent a signal, which betrayed his position at all times. Then I put one of these direction finders in my cap, and I could move about and always know where the bears were.

“Well, Floyd Calendar discovered who manufactured the broadcasting and listening devices, and after that whenever he captured a bear to be used later, he planted one of these transmitters around his neck. Then when a sportsman came into the mountains to get himself a bear, all Floyd had to do was let the bear loose, listen to where he was going, and zero his hunter right onto the scene without any chance of failure.”

“Didn’t the hunter realize what was happening when he got to the dead bear and saw the broadcast device?”

“No. Because Floyd never let him shoot at the bear till he—Floyd, that is—was all set for a running start. Then, while the hunter jumped in the air with joy, Floyd ran in, bent over, and with one quick swipe, tore the little transmitter from the bear’s neck, and no one was the wiser.”

Now came the turn of Paul Garrett, who was introduced as deputy to the commissioner. Spectators in the courtroom leaned forward as he took the stand, because feelings ran high in this case, and some citizens felt that it was unfair to confront Calendar with an official like Garrett.

“I’ve known Floyd Calendar all my life,” Garrett said under questioning. “Knew his father, too. And my family knew his grandfather.”

“Tell us about Mr. Calendar and turkeys.”

“About ten years ago I lured a family of wild turkeys onto the north edge of my ranch. We fed them, protected them, and after a while we had quite a colony. The wild turkey is a very sensitive bird, almost extinct in these parts, and we watched our brood very carefully, because they’re our real national bird.

“But apparently Floyd Calendar was watching them too, because after they reached a certain number they began to decline, and we could find no sign of coyotes. We worried about this until a friend of mine in Massachusetts sent me a copy of a form letter he’d received from Colorado. Here it is.”

The judge instructed the clerk to read it, and the spectators were either amused or outraged when Floyd Calendar’s mimeographed letter to his clients was divulged: “I can make you a guarantee that no other guide in America can make. Come to the Rockies and I’ll show you how to bag both of our national birds, a baldheaded eagle and a wild turkey.”

“Where did he get the turkey?” the prosecutor asked.

“From my protected sanctuary. When I saw the letter I staked one of my men out to guard the turkeys, and sure enough, here comes Floyd Calendar with a hunter from Wisconsin, shooting my turkeys.”

“Now, Mr. Garrett, there are rumors circulating as to what you did then. Will you tell the court.”

“I became very angry and waited till I saw Calendar go into Flor de Mèjico, that’s the restaurant run by Manolo Marquez, and I went up to him and I said something like …”

“We don’t want to hear ‘something like’ what you said. What did you say?”

“As well as I can remember, I said, ‘Calendar, if you ever set foot on that turkey range again, I’ll kill you. If I’m there when you come, I’ll do it there. If I miss you when you sneak in, I’ll come into this restaurant and get you while you’re eating.’ ”

“Did you say, Mr. Garrett, that you’d get him while he was eating?”

“I did. I was very angry.”

This early confession of his threat took some of the sting out of the cross-examination, but the defense attorney made a good deal of the fact that a man who would be working with sportsmen in his new job had threatened to shoot one of them in a public restaurant. By the time the interrogation ended, Garrett did not look good.

The last prosecution witness was a Centennial man who had had several run-ins with Calendar, and his testimony was devastating: “With Floyd Calendar, killing became an end in itself. He hated everything that moved—prairie dogs, rattlers, antelope and, like you heard, bears and eagles. I think if you gave Floyd a free hand, when he got through with the animal kingdom he’d start on Negroes and Mexicans and Chinese and Catholics and anyone else who wasn’t exactly like himself. He hates anything that intrudes on his part of the world, and considers it his duty to wipe it out. To call him a sportsman is obscene. He’s a one-man ecological disaster.”

The defense attorney, of course, objected to this whole tirade, and the judge ordered it stricken from the record.

When the first defense witnesses appeared the general tenor of the trial became clear, for they were ranchers and hunters who testified that bald eagles carried away young lambs and should therefore be exterminated. They also testified that Floyd Calendar was one of the finest men in the west—everyone said he had been kind to his mother—and on that edifying note the court recessed over the weekend. One rancher, as he left the courtroom, told Garrett, “You have a nerve, testifyin’ against a real American,” and Paul was relieved to know that he would be required to testify no further.

On Saturday, November 10, he worked on the ranch, riding north to inspect the wild turkeys. They were most handsome birds, big and heavy. They always looked as if Pilgrims with long guns should be chasing them for the 1621 Thanksgiving, and Paul was delighted that they shared the ranch with him.

He also rode over to a corner of the range he had set aside for a prairie-dog town. Slowly the little creatures were making a comeback, sharing their burrows with sand owls. Their return was not an unmixed blessing, for one of Garrett’s horses broke his leg in a burrow and had to be shot. The ranch foreman wanted to bulldoze the town out of existence, but Garrett refused permission: “You preserve nothing without encountering some disadvantages. If we keep this dog town, horses will break their legs and rattlers will come back. But in the large picture, things balance out, as they did two thousand years ago. The trick is to preserve the balance and pay whatever price it costs.”

The fact that he had sought the company of turkeys and prairie dogs reminded him of how deeply he was afflicted by the permanent American illness. A deep depression attacked him, which he could identify but not explain, the awful malaise of loneliness:

I’ve never understood why so many Americans are so committed to loneliness. I know it runs in my family. When Alexander McKeag, who could be called an ancestor because he held Pasquinel’s family together, spent the winter of 1827 alone in a cave, speaking to no one, he was succumbing to our sickness.

And when my other ancestor, Levi Zendt, turned his back on Beaver Creek and chose the dreadful isolation of Chalk Cliff, he was behaving like a typical American.

Sheepmen like Amos Calendar elected to live by themselves. Like their prototype Daniel Boone, they preferred living alone “rather than with all them people.”

Only the white Americans did this. The Arapaho always combined in large communal societies. Chinese railroad workers lived in colonies, and so did Chicano beet workers. The Japanese clung to their communities and so did the Russians. It took the American to build his ranch far from everything, his farm where no one else could see him. Why?

Garrett had assembled various theories about this American preference for isolation. When a Pilgrim was thrown onto the shore at Plymouth he faced only wilderness, and from it each man had chopped out his own little kingdom. He had to wrestle with loneliness, learn to live with it and overcome it. If he could not do this, he could not survive. Traipsing off to the town meeting was not the basic characteristic of New England life; it was going back afterward to the loneliness of one’s own cottage.

It had been the same with all subsequent frontiers. If a man was inwardly afraid of loneliness, he had small chance of adjusting to the terrible isolation of the Kentucky forest. A predisposition for living alone became almost a requirement for survival in America, and even now, Garrett thought, the world held few places so lonely as the average American city.

The prairie had intensified the challenge, for there the emptiness was inescapable; even the sheltering tree was absent. A family moving west could anticipate fifty days of travel without encountering a sign of human habitation, and the wife whose husband decided to settle in Wyoming had to face an endless expanse of nothingness.

And there had been that ultimate in isolation, the snowbound mountain man passing the winters in some forgotten spot, allowing the drifts to cover him during the silent months, reading nothing, conversing not even with animals, who were also in hibernation. This was a form of exile difficult to comprehend, but there were always men who sought it.

The only heroes I had as a boy were loners. The isolated defenders of the Alamo. Nathan Hale operating alone and taking his punishment solo. The pioneer mother defending the Conestoga wagon after her man was slain. The Pony Express rider pointing the nose of his horse west and going it alone. These were my symbols.

This had an effect on every aspect of American life. One courageous man building a solitary log cabin and calling it home. Any self-respecting family must live apart … by itself … in its own little cabin, and any unfortunate who failed to achieve this alone-ness was either pitied or ridiculed. The unmarried elder sister became the focus of pity because she had to live with others. Any son-in-law who had to live with his wife’s parents was an object of ridicule.

When the west was opened, people did not live in communities. One ranch was thirty miles from the next. During the period of Indian raids no one gave the remote settler hell for trying to make it alone. He was cheered for being brave enough to face the Indians on his own.

As a consequence of all this, Americans became the loneliest people on the face of the earth. We’re even lonelier than the Eskimos, who live in close units. We’re much lonelier than the Mexicans, who occupy the same type of land to the south, for Mexicans retain the extended family in which people of all ages live together in reasonable harmony.

There were compensations, Garrett had to admit. Living alone meant that men had to be more ingenious, which led to inventiveness. Old patterns had to be surrendered, so revolutionary new ones could be more easily accepted. Forward-seeking led to the development of the brash, resolute, outgoing man. The world needed him, but he evolved at a terrible price in loneliness.

For Garrett was also aware of the heavy social cost. Americans were both wasteful and cruel with their old people, especially their older women. Three factors conspired to produce a plethora of elderly women. First, as in all nations, females tended to live about five years longer than males. Second, custom encouraged a man to marry a woman somewhat younger than he. Third, American tradition required the man to work himself to death to support his woman, so that many men died prematurely. Adding these data, the average wife could look forward to about fifteen years of widowhood.

Other civilizations had grappled with this phenomenon. The American Indian who used to live at Rattlesnake Buttes solved it by depriving the widow of everything, even shelter, and encouraging her to starve to death. Asian Indians adopted a crueler solution: the widow was expected to climb the funeral pyre of her husband and burn to death. Arab nations developed the sensible device of multiple wives. In America, Garrett saw, the survivors were condemned to infirmity and loneliness.

Men fared only slightly better. Some of the loneliest men Garrett had ever known were the heads of corporations, trusting no one, confiding in no one, living out their lives in quiet despair, each wealthy man immured within his own castle.

What the hell am I doing living in a castle? he asked himself as he returned to ranch headquarters. Since the death of his wife he had been terribly lonely, felt himself no better off than the widows and the tycoons he had been pitying. He had a fine ranch, a profession he loved and now a responsible job with the government, but these did not compensate for his increasing sense of isolation.

About three o’clock that afternoon he took a shower, shaved and climbed into his car. When he left the ranch he could not have said where he was heading. Vaguely he wanted to hear Cisco Calendar sing some good western songs, for Cisco was the best in the business and was home again from his television show in Chicago. He also wanted to assure Cisco that his testimony against Floyd indicated no grudge.

But Cisco was not the main reason for the trip to town. What he really needed was to see Flor Marquez, to make up his mind about that long-legged, dark-haired divorcee. She had first caught his eye during his visits to her father’s restaurant for some good Chicano food. It could not be said that he watched her grow up, for he was too preoccupied with other things to notice a Chicano girl, but he was aware that she had married a dashing fellow from Los Angeles, and of course it was a general scandal when she returned home after two weeks with a scar along her left cheek.

She had referred to her marriage only once: “How can a girl tell that a guy is a total creep?”

She was in the restaurant when Garrett arrived. “Let’s go see if Cisco will sing tonight,” he suggested, and she was eager for an excuse to leave the restaurant. They walked west on Mountain, then down Prairie and along the railroad tracks to where Cisco lived in an old clapboard house. He was sitting on the porch, as he usually did in the afternoon, just watching things go past. Like his older brother, he was tall and lean, with the face of a man long accustomed to outdoor work.

“Hiya, folks,” he said amiably, without getting up.

“Came by to tell you I’m sorry about the run-in with Floyd … in court, that is.”

“He’s a mean one. Anything you said was probably true.”

“I only testified about the turkeys.”

“How they doin’?”

“Checked them this morning. There they were, fat and sassy.”

“Come on over tonight,” Flor said. “Give us some songs.”

“I just may do that,” Cisco said.

They knew it was unnecessary to say anything more. If he felt like it, he would stop by Flor de Méjico around ten and entertain his neighbors. Flor knew that in places like Cleveland and Birmingham he could command thousands of dollars for a night’s performance, but when at home he liked to associate with the people from whom he had learned his songs, the Chicanos and the cowboys.

Garrett and Flor walked back to the Railway Arms, where they stopped for a couple of beers. They were aware that townspeople were watching them, and that there had been a good deal of talk. Gossips claimed that Flor was his mistress, but a waitress who knew her said, “That hot tamale ain’t gonna let no man in her bed without a license.”

She was wrong. In various rooms in various towns Flor Marquez and Paul Garrett had been lovers for some time now, each wary of the other, each uncertain of what the future could be. On this afternoon, when each was feeling desolate with loneliness, they separated at the hotel, then found their way by back paths to a motel, where they stayed through the early evening.

About nine they slipped away, at different times and by different paths, to join me at the restaurant. Flor arrived first and made a desultory effort at helping her father serve the dinner crowd, and after a while Garrett drifted in, as he often did, to play the juke box.

At ten there was a commotion. “Cisco’s coming!” a boy at the door shouted, and in came the lanky singer with his guitar. Nodding to various friends, he made his way to where Garrett and I were sitting, then invited Flor to join us. He drank beer for about an hour, answering the questions of well-wishers who wanted to know about Nashville and Hollywood, and finally he took up his guitar, plucking a few notes.

Without warning he struck a series of swift chords, then placed the guitar on the table. “What would you like to hear, Paul?”

It really didn’t matter, for whatever Cisco Calendar sang evoked the west. If he sang of buffalo skinners, he called forth images of his own grandfather during the big kill of 1873, with his Sharps .50 firing until it was too hot to handle. If he sang of the dust bowl, he reminded listeners of his own father, Jake, who had gone broke in 1936 after watching his farm blow away; when his wife wouldn’t stop nagging him, he blazed away at her with a shotgun and spent a year in jail.

And if Cisco sang of cowboys, people could hear in his high, nasal complaint the rush of the tumbleweed or the harsh dissonance of a rattler coiled in a sandy path. He could sing of the hawk and the eagle and the Indian’s pinto and make the listener see these creatures, for he had in his manner a terrible reality, the art of a man who had absorbed a culture and found its essence.

“I’d like to hear ‘Malagueña Salerosa,’ ” Garrett said, and Cisco looked at him.

“That’s a tough one to start with.”

“I didn’t say it was easy.”

Cisco lifted the guitar and played the unique chords which framed this love song, perhaps the finest written in North America in the past fifty years. It was difficult to sing, requiring a command of Spanish-type falsetto, but Cisco respected it as the best of his Chicano repertoire:

“What beautiful eyes she has

Beneath those dark brows …

Beneath those dark brows …

What lovely eyes …”

The Chicanos in the restaurant applauded as he sang a passage in high falsetto. After finishing the song, he placed the guitar on the table and bowed to the applauders. “I am singing this song for my good friend Paul Garrett and my better friend Flor Marquez, who are in love.” Recovering the guitar, he played a long passage based on the theme of the song, then sang tenderly the exquisite conclusion:

“I offer you only my heart …

I offer you my heart

In exchange for my poverty …

She is pretty and bewitching

Like the innocence of a rose …”

With the last word he strummed the guitar softly and bowed again. He avoided the popular pitfalls like “Cool Water” or “Ghost Riders in the Sky” or “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie,” apologizing, “Those songs are for the boys with strong voices. I’m after somethin’ different, altogether different.”

As he unraveled bits and pieces of the songs he really loved, he built a portrait of a west that no longer existed but which men wanted to remember. Single phrases often evoked a whole era: “Beat the drum slowly and play the fife lowly.” Or “On a ten-dollar horse and forty-dollar saddle, I’m off to punch them Texas cattle.” Or “His wife, she died in a poolroom fight.” Or “Clouds in the west, it looks like rain. Derned old slicker’s in the wagon again.”

He sang for several hours—the last of the real cowboys, the last of the buffalo men. He had enjoyed great popularity in Europe as well as in the eastern cities, but he felt most at ease in the restaurant of Manolo Marquez, who had fed him free during the bad years. Here he had learned most of the good Chicano songs he sang, like his very popular translation of “The Ballad of Pancho Villa,” which American audiences appreciated for its outrageous nationalism.

But the highlight of any Cisco Calendar performance always came late at night, as it did now. Nodding to Garrett and Flor, he played the famous opening chords of the song they waited for. The words were as taut as Homer’s and strove for the same effect: the beginning of a memorable saga:

“ ’Twas in the town of Jacksboro in the year of ’73

A man by the name of Crego comes steppin’ up to me,

Says, ‘How d’you do, young feller, and how’d you like to go

And spend one summer pleasantly on the range of the buffalo?’ ”

The song had excellent touches—the smell of the west, the Indians, the tense narrative, the petulant cowboys:

“It’s now we’ve crossed Pease River, boys, our troubles have begun.

First damned buffalo that I skinned, Christ, how I cut my thumb!”

Now Cisco became something larger than life, an epic figure chanting in the darkness of the wild, free days that were no more. Sitting very straight, and moving his hands as little as possible, he approached the end of his song with the inevitability found in Greek tragedy:

“The season was near over, boys, Old Crego he did say

The crowd had been extravagant, we were in debt to him that day.

We coaxed him and we begged him, but still it was, ‘No go!’

So we left his damned old bones to bleach on the range of the buffalo.”

“The Buffalo Skinners” was the name of this splendid song. Its composer? No one knew, but the music hammered with the beat of buffalo hoofs on the prairie. Its lyricist? Some nameless Texas cowboy, down on his luck, who had tried his hand at buffalo-skinning during the year of the last great hunt.

“Well, that’s it,” he said as he finished. “If I was you two,” he said quietly to Flor and Garrett, “I’d get married and to hell with them.”

I did not see Garrett on Sunday, for he spent the day with Flor, talking seriously about the problems that would arise if they did marry. He was Episcopalian and she Catholic, but that was of no consequence to either of them. He had two children, and they were at a difficult age … well, all ages were difficult when a widower sought to remarry, because the children rarely approved, no matter whom he chose. The young Garretts had already stated that they would not like the idea of a Chicano stepmother. The principal objection, of course, had been removed by the death in February of Paul’s mother, Ruth Mercy Garrett. She had been a tense, unlikable woman who had always known of her husband’s protracted love affair with Flor’s great-aunt, Soledad, and because of it she despised Chicanos. When she heard that Paul was seeing Flor Marquez, a divorcee to boot, she put on a terrible scene, accusing her son of trying to hasten her death. She was so irrational that Paul could not discuss the matter with her, but he honestly believed that his mother might indeed have a heart attack if he married Flor, especially after she bellowed at him, “You’re just like your father! You’re carrying on with that Mexican hussy merely to spite me, the way he did.” Now she was gone and no one deplored her passing, not even her grandchildren, whom she had tried to pamper but who saw her for what she was—a miserable, self-pitying, self-destroying woman.

One of the real obstacles was Manolo Marquez, for he saw little chance that an Anglo-Chicano marriage might succeed. The few he had witnessed had turned out disastrously, and he doubted that Flor and Paul would do much better. Flor respected what he had to say, because while she was preparing for her first marriage he had predicted that it couldn’t last two months, and it had crashed after only eleven days.

“He’s a flashy macho,” Manolo had warned his daughter. “But you wouldn’t recognize the type because you don’t hang around poolrooms.” No description could better fit her unfortunate husband, a strutting would-be hero with ideas about the rights of the male in marriage so bizarre that one couldn’t even be amused by them. Flor was humiliated that she had been such a miserable judge of human behavior and felt little confidence in her belief that Garrett might be different.

But all doubts withered in face of the fact that she and Paul loved each other, wanted each other and felt like better people when in each other’s company. Sex with her first husband had been an appalling affair, without feeling or fulfillment, but to share a bed with Paul Garrett was totally satisfying. He was not afraid of letting her know that he needed her.

On this Sunday, for example, when they had made their way to the motel again, he told her, “I’m so lonely I can hardly bear it. I stay up there in the castle surrounded by acres of empty land, and they insulate me from everything. If I couldn’t see you in the restaurant, I’d go batty.”

It became obvious to each that they ought to get married. What held them back? It simply was not the custom in Colorado for Anglos to marry Chicanos. To marry an Indian was acceptable, but a Chicano? No!

Paul spent Monday away from Flor, trying to sort out his convictions. He applied himself to the job of getting the centennial commission functioning, and since one of his plans called for widespread use of radio, he needed to know what that medium was doing, and the more he heard, the more disgusted he became. On this day he wanted a tape of the major noon broadcast from the local station, and here is the complete transcription:

FIRST MALE ANNOUNCER: Well, folks, it’s high noon and the train is chuggin’ in from Poison Snake and Sheriff Gary Cooper is a-waitin’ at the station.

SECOND MALE ANNOUNCER: It’s time for news, all the news, the straight news, delivered without fear or favor, the news you want when you want it.

FEMALE QUARTET (singing in close harmony):

“From north from south,

From east and west,

We bring it first,

We bring it best.”

FIRST MALE ANNOUNCER: Yessiree, like the girls just said, we bring it best. Remember you heard it first on Western Burst.

MALE AND FEMALE QUARTETS (blending):

“The news, the news, the news!

Here comes the news.”

SECOND MALE ANNOUNCER: But first a brief message which is sure to be of interest. (Here followed two minutes of singing commercials.)

FIRST ANNOUNCER (breathlessly): West Berlin, Germany. This morning Chancellor Willy Brandt announced a radical shift in his cabinet.

SECOND ANNOUNCER (gravely): Oakland, California. At a special press conference called hurriedly this morning the management of the Oakland Raiders announced that Choo-Choo Chamberlain would—I repeat would—be able to play Sunday against the Denver Broncos.

MALE AND FEMALE QUARTETS (blending):

“No matter when the stories burst,

You hear it here, you hear it first.”

FIRST MALE ANNOUNCER: Stay tuned for all the news, the news in depth, the news behind the news.

MALE AND FEMALE QUARTETS (blending):

“All the news, the news you need.

Yes indeed. Yes indeed.”

FIRST MALE ANNOUNCER: Next complete news coverage one hour from now.

SECOND MALE ANNOUNCER: Unless, of course, there is some fast-breaking news development anywhere in the world. If there is, you know we break in right away, regardless of the program. Because Western Burst is always first. All the news, the news in depth.

Resignedly, Garrett leaned forward and clicked off the set. Radio and television could have been profound educative devices; instead, most of them were so shockingly bad that a reasonable man could barely tolerate them. In one spell last winter television had offered him an automobile that talked, a housewife who was a genie, a village idiot who could move forward and backward in history, and eighteen detectives involved in forty-seven murders. When one station did run the B.B.C. series Six Wives of Henry VIII, the newspaper announced the first episode as a western, Catherine of Oregon.

There was the same illiterate cheapening in every aspect of life. One local restaurant had a big sign advertising its specialty, “Veal Parma John.” Another proclaimed, “Broken Drum Café. You Can’t Beat It. Our Chicken Has That Real Fowl Taste.” A refreshment booth featured “Custard’s Last Stand,” while a motel sign flashed “Just a Little Bedder.”

One gap in Colorado’s cultural life perplexed him. The state had no major publishing program, and whereas its history was perhaps the most varied and vital in the west, there were few local books to celebrate it. This was the more remarkable in that two neighboring states, Nebraska and Oklahoma, each had a university press which produced really fine volumes on western themes; Garrett was pleased that they kept him supplied with the books he needed but thought it deplorable that Colorado, a richer state with a better subject matter, published almost nothing, as if it were ashamed of its history.