OLMSTED, VAUX & CO. prospered. The partners planned a zoological garden near Central Park and a college campus in Maine. The Brooklyn park commissioners asked them to look at Washington Park, which was dilapidated and needed a thorough overhaul. Olmsted’s friend Potter owned land in New Jersey and wanted landscaping advice; so did Francis George Shaw, George Curtis’s father-in-law, who had an estate on Staten Island. Andrew Dickson White, the first president of the university founded by Ezra Cornell in Ithaca, consulted them about a new campus. The trustees, who had approved a plan whose chief feature was a formal quadrangle, resisted Olmsted’s proposal for a more irregular layout. He enlisted the help of his friend Charles Eliot Norton to influence the university president.

Norton, too, had become a client. He wanted to subdivide his family estate in Cambridge and engaged Olmsted to draw up the plans. During one of Norton’s visits to New York, they resumed their discussion of Olmsted’s book on American civilization. With Norton’s help, he continued to accumulate research material. He was making slow progress—he did not have enough time. The daunting task of collating the statistics from the Sanitary Commission—more than eight thousand completed forms had to be classified and analyzed—remained. He wrote to Frederick Knapp asking him to undertake the task. Olmsted planned to work on the manuscript during his summer vacation.

But the summer of 1868 proved to be one of Olmsted’s busiest. In August he received a letter from William Dorsheimer, who had written two years earlier for advice about a public park for the city of Buffalo. Now, as head of a private committee of leading citizens, he was extending a formal invitation. Buffalo was one of the ten largest cities in the United States. It had prospered because of the Erie Canal and was now a grain-handling port as well as an important meatpacking and iron-manufacturing center. Olmsted, who was leaving that weekend for Chicago, immediately altered his travel plans to include a stopover in Buffalo.

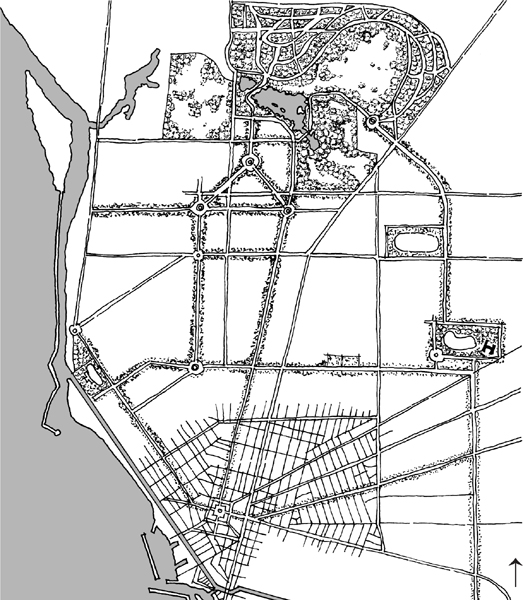

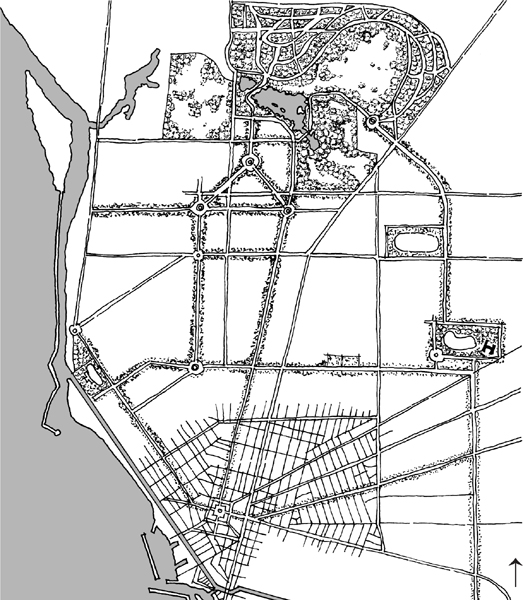

Buffalo, New York (1876).

He was accompanied on this trip by one of his employees, a young engineer named John Bogart. On Sunday, August 16, they arrived in Buffalo, where they met Dorsheimer, who forthwith took them on a quick tour of several potential sites. He was the U.S. district attorney for northern New York State and, like Olmsted, a member of the Century Association. During the war he had served as a colonel and been active in the Sanitary Commission. Olmsted was impressed by his no-nonsense approach. “The business opened at once & promisingly,” he wrote Mary in one of his regular letters. He agreed to make a presentation to Dorsheimer’s committee on his way back from Chicago.

Olmsted and Bogart returned to Buffalo exactly one week later. Olmsted discovered that he was to address a public meeting of two hundred civic leaders the following Tuesday. The meeting would be chaired by former president Millard Fillmore, who lived in Buffalo. Fillmore was not just a figurehead. As president, he had actively supported A. J. Downing’s plan for a public grounds in Washington, D.C. This august Buffalo assembly was expecting “to hear an address on the matter of a public park from the distinguished Architect of the N.Y.C.P. Fred Law Olmsted Esqr,” Olmsted wrote to Mary. He and Bogart got down to work. On Monday morning, they drove out to the sites. They made a quick survey and dug test pits to ascertain the nature of the ground; by nightfall they were half-done. They completed the work the next day. That evening Olmsted spoke at the meeting. He had contracted a cold on the train and had a sore throat, but managed to talk for an hour, he wrote to Mary, “with tolerable smoothness and I should think with gratifying results. At any rate the men who started it were very much pleased & encouraged.”

Dorsheimer’s committee had reason to be pleased. Olmsted did not merely give a general talk about cities and public parks, he sketched out a specific park plan for Buffalo. He had been shown three alternative sites. The largest, in an undeveloped area four miles north of the city, was 350 acres. The second site, about two miles from the center of town, was much smaller, 35 acres. It occupied a dramatic bluff overlooking the mouth of the Niagara River. The third site was located on high ground and afforded a panorama of the city and Lake Erie.

Olmsted proposed that the city acquire not one but all three sites. The large tract would be made into what he called the Park. He pointed out that the undulating ground and profusion of trees would require little beautification; Scajaquada Creek, which flowed through the valley, could easily be dammed to create a lake. The riverside park he called the Front. It would have a promenade and a waterfront terrace that could be used for civic ceremonies. The third park would be the Parade; it would serve for more active recreation. The three sites approximated the shape of a huge baseball diamond, with downtown Buffalo at home plate, the Parade at first base, the Park at second, and the Front at third. The distance between the “bases” was two to three miles. Olmsted proposed parkways and tree-lined avenues to link the parks with each other—and with the downtown. In two hectic days, he had conceived this extraordinary tour de force—the outlines not of a park, but of an ambitious park system. If carried out, this master plan would govern the growth of Buffalo for years to come.

“I did a deal of talking privately & publickly [sic]—was cross examined &c & got thro very well,” Olmsted wrote Vaux, who was then in England. Olmsted enclosed a newspaper clipping that described the evening’s proceedings. “At least the project was advanced materially, I was told, & they will go to the Legislature in January for a Commission.” Dorsheimer’s committee, at its own expense, engaged Olmsted to prepare a preliminary report, which he submitted on October 1. Since Vaux did not return to America until November 16, this early work can definitely be attributed to Olmsted. He emphasized the need for a far-reaching solution. “We should recommend that in your scheme a large park should not be the sole object in view, but should be regarded simply as the more important member of a general, largely provident, forehanded, comprehensive arrangement for securing refreshment, recreation and health to the people.” The Park was a version of Prospect Park, with a large meadow and a lake. The idea of parkways was based on the plans that Olmsted and Vaux were carrying out in Brooklyn. Yet the scale and extent of the project were unprecedented in their work. Olmsted’s interest in city planning had its genesis in his proposal for San Francisco; in Buffalo, he was given the opportunity to put it all together.

Buffalo had been planned in 1804 by Joseph Ellicott, the brother of Andrew Ellicott, collaborator and successor of L’Enfant in Washington. The focus of the plan was a large square—later named Niagara Square—from which eight avenues radiated like the spokes of a wheel. Olmsted admired Ellicott’s design. His proposal refined rather than altered the street pattern. He planned to widen several of the major streets to one hundred feet to create treed avenues. Among these was Delaware Avenue, which became the main approach from Niagara Square to the Park. From the Park, a mile-long, two-hundred-foot-wide parkway would lead to a large rond-point on the scale of the Place de l’Étoile in Paris. From this circle, two additional parkways would radiate to two more formal squares.

The Parisian influences in Olmsted’s proposal are obvious. They are at odds with his later reputation as a proponent of winding streets and picturesque planning. He was nothing if not pragmatic. Indeed that was the strength of this plan. It is not a geometric diagram nor a theoretical construction imposed on the city. Unlike his San Francisco plan, it does not depend on a single idea. Nor, despite his respect for Ellicott, did Olmsted produce a version of European neo-baroque planning such as would later be revived by the City Beautiful movement. He was no historicist. Instead, his highly original plan was a complex and refined network of parks, parkways, avenues, and public spaces that represented a degree of sophistication in city planning previously unknown in the United States. He distributed parks throughout the city to make recreation space more accessible. Elsewhere, broad avenues and parkways brought trees and greenery into the congested grid of streets. In Buffalo, Olmsted showed how the burgeoning American industrial city could be made livable.