Frederick Law Olmsted’s father owned a dry-goods store in Hartford, Connecticut. The small-town Main Street, shown here in 1863, had not changed much since Olmsted’s youth, except for the streetcar lines. The store was halfway down the street, on the right side of the photograph.

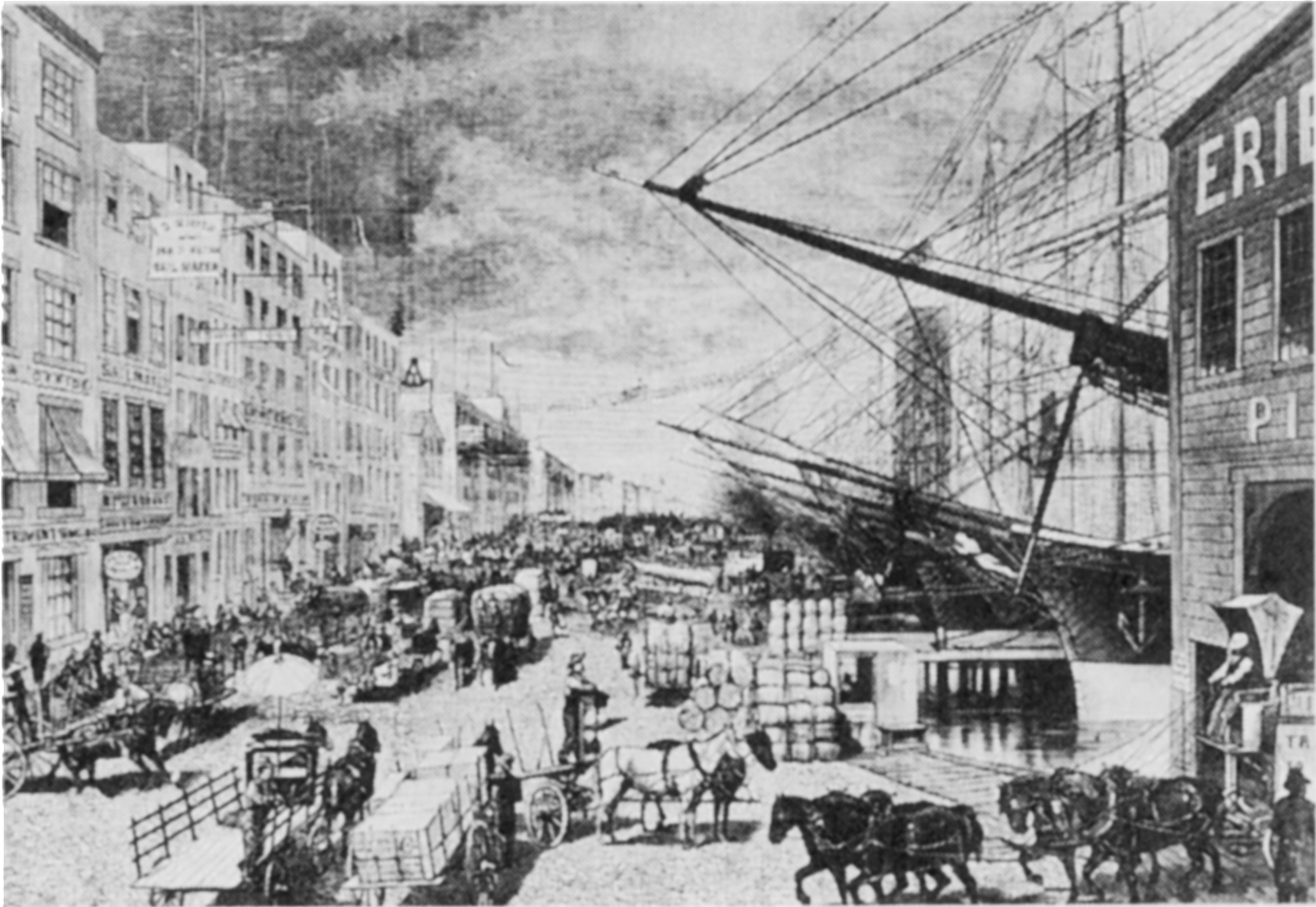

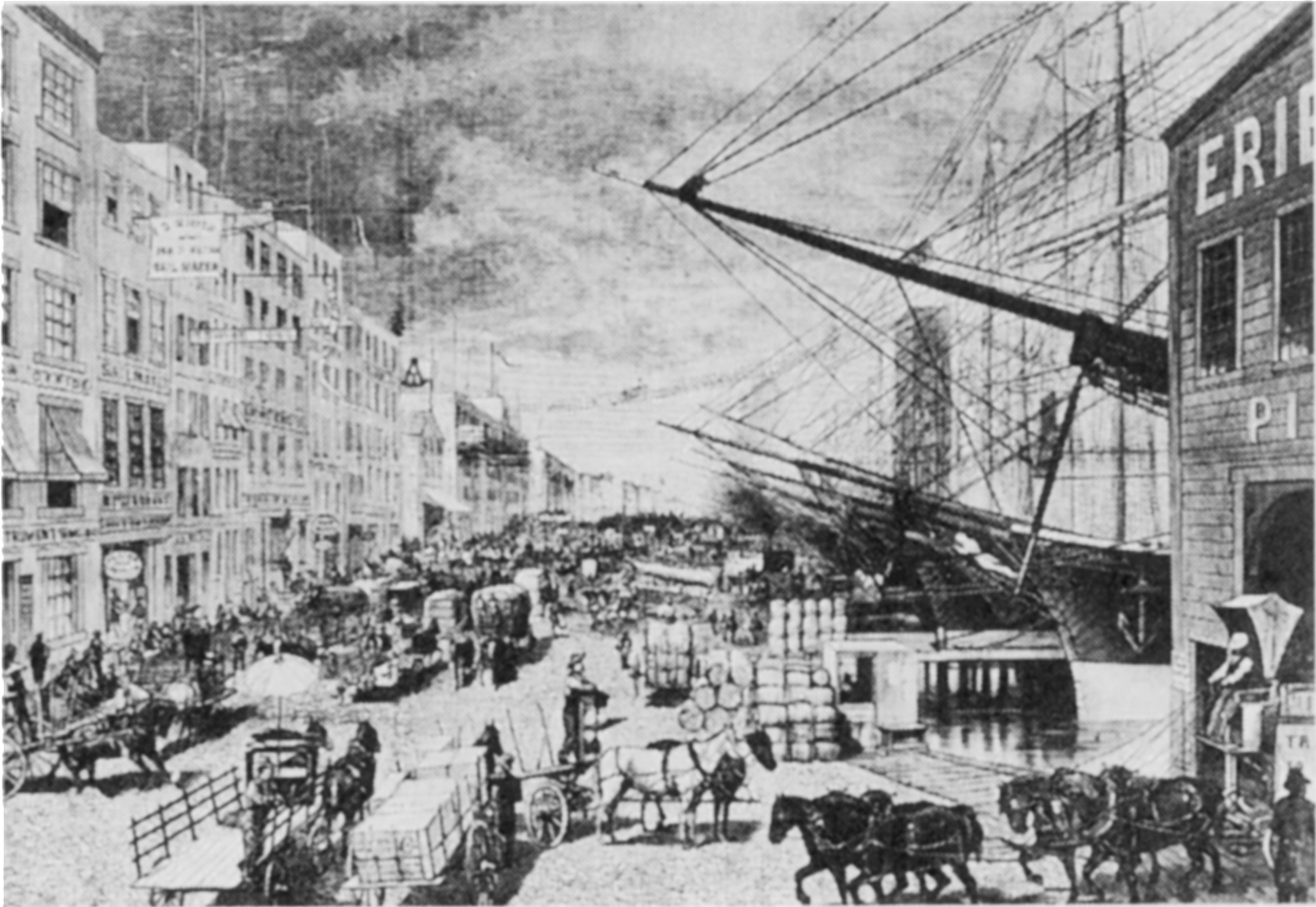

Bustling South Street in New York, where as a young clerk in 1840, Olmsted went on board sailing ships to tally cargo for the importing house of Benkard & Hutton.

The twenty-one-year-old Olmsted sailed to China as an ordinary seaman on a merchant ship. He reached Whampoa, the port of Canton, but only managed to go ashore three times.

Olmsted witnessed more than one slave-whipping while traveling in the South as a correspondent for the New-York Daily Times. His book, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, in which this illustration appears, was published in 1856.

This engraving from the 1857 edition of Olmsted’s A Journey Through Texas is based on one of his sketches. It shows him and his brother, John, camping in west Texas. They named the bull terrier Judy; the pack mule, Mr. Brown.

During the Civil War, Olmsted was secretary general of the United States Sanitary Commission, which operated field hospitals, dispensaries, and hospital ships and employed scores of surgeons, nurses, and health inspectors. Of his women volunteers, Olmsted said: “They beat the doctors all to pieces.”

Oso House, in Bear Valley, on the California frontier, astride the Mother Lode. Olmsted spent two years here managing the vast Mariposa Estate, a gold-mining operation. The stagecoach carried people and mail to the closest large town, eighty miles away.

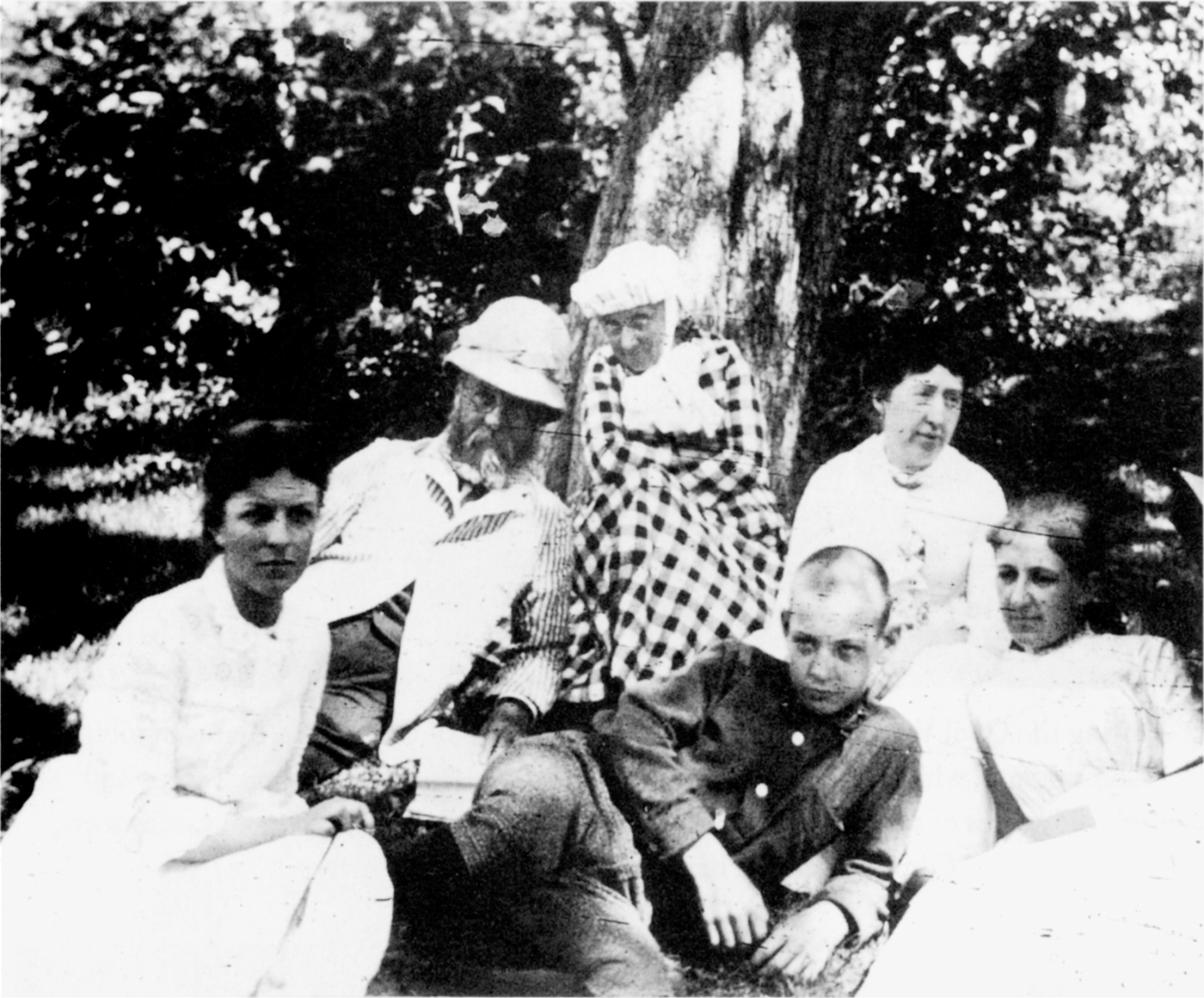

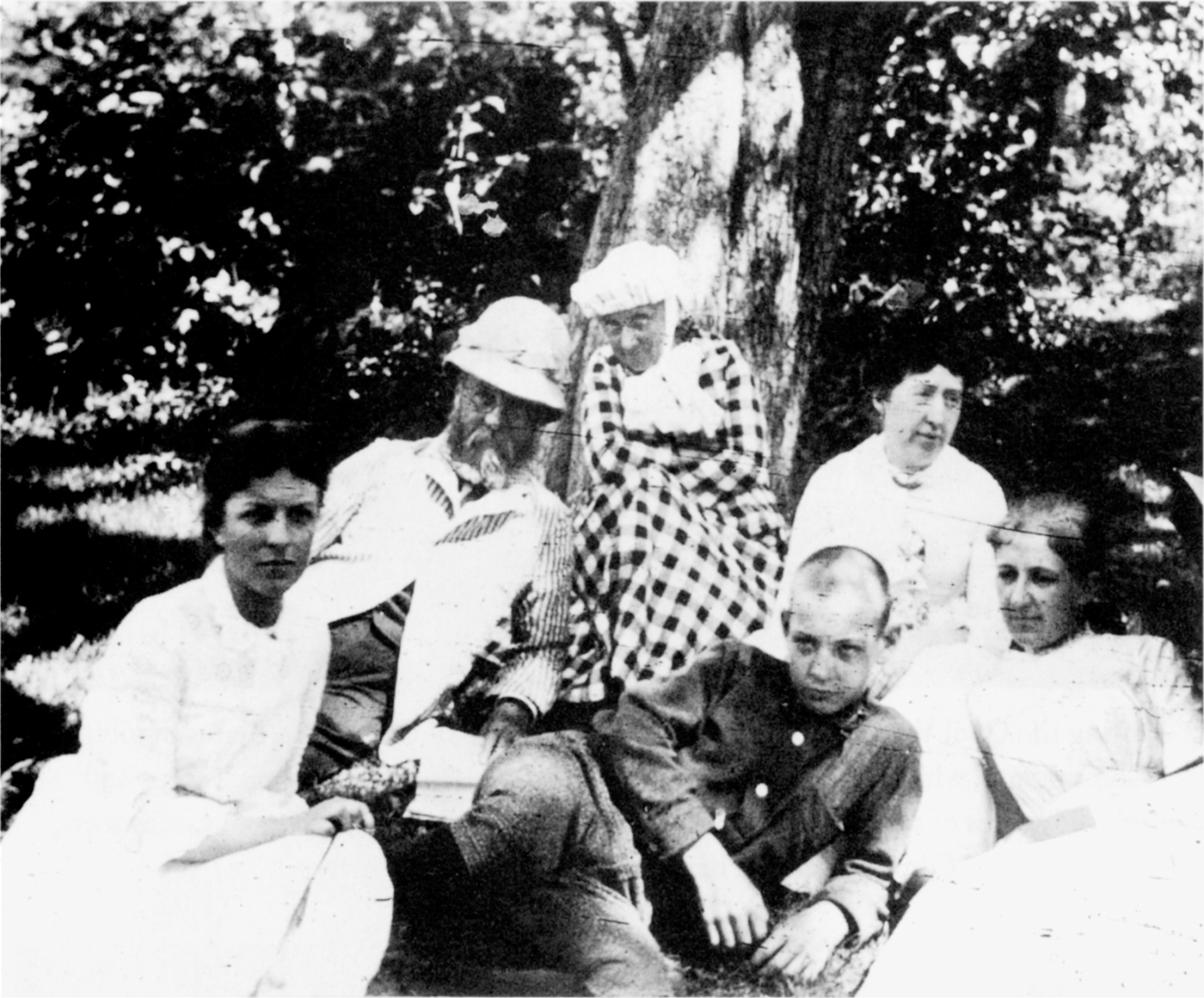

John C. Olmsted took this family photograph in July 1885. Olmsted, wearing a pith helmet, is flanked by his two children, Marion and Rick; his wife, Mary, is leaning against the tree. The two women on the right are unidentified guests.

Frederick Law Olmsted, circa 1890. “What a good ancient philosopher you look like!” exclaimed his friend Charles Eliot Norton.

Shy and diffident, Olmsted’s stepson, John C. Olmsted, became a partner in F. L. & J. C. Olmsted, Landscape Architects. He played a major role in the design of the Emerald Necklace, Boston’s extensive park system.

Visitors to Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, looking down from the roof of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts building at the basin that was the focus of the Court of Honor. Olmsted picked the site beside Lake Michigan and planned the fairgrounds.

The builders of Biltmore. On the left, behind Olmsted, is the architect, Richard Morris Hunt; on the right, the young client, George W. Vanderbilt.

Frederick and Mary Olmsted at Biltmore Estate in the early 1890s, not long before he withdrew from active practice. Olmsted not only designed the gardens and parkland surrounding the house, but also established an extensive, scientifically-managed forest.

Fairstead, Olmsted’s home and office in Brookline, Massachusetts. “Less wildness and disorder I object to,” he once said of his garden.

It was in McLean Asylum, in Waverly, Massachusetts, whose grounds he had earlier designed, that Olmsted spent his final years.

Central Park, New York

It takes decades to realize the landscape architect’s vision. Patience and long-sightedness were among Olmsted’s chief qualities.

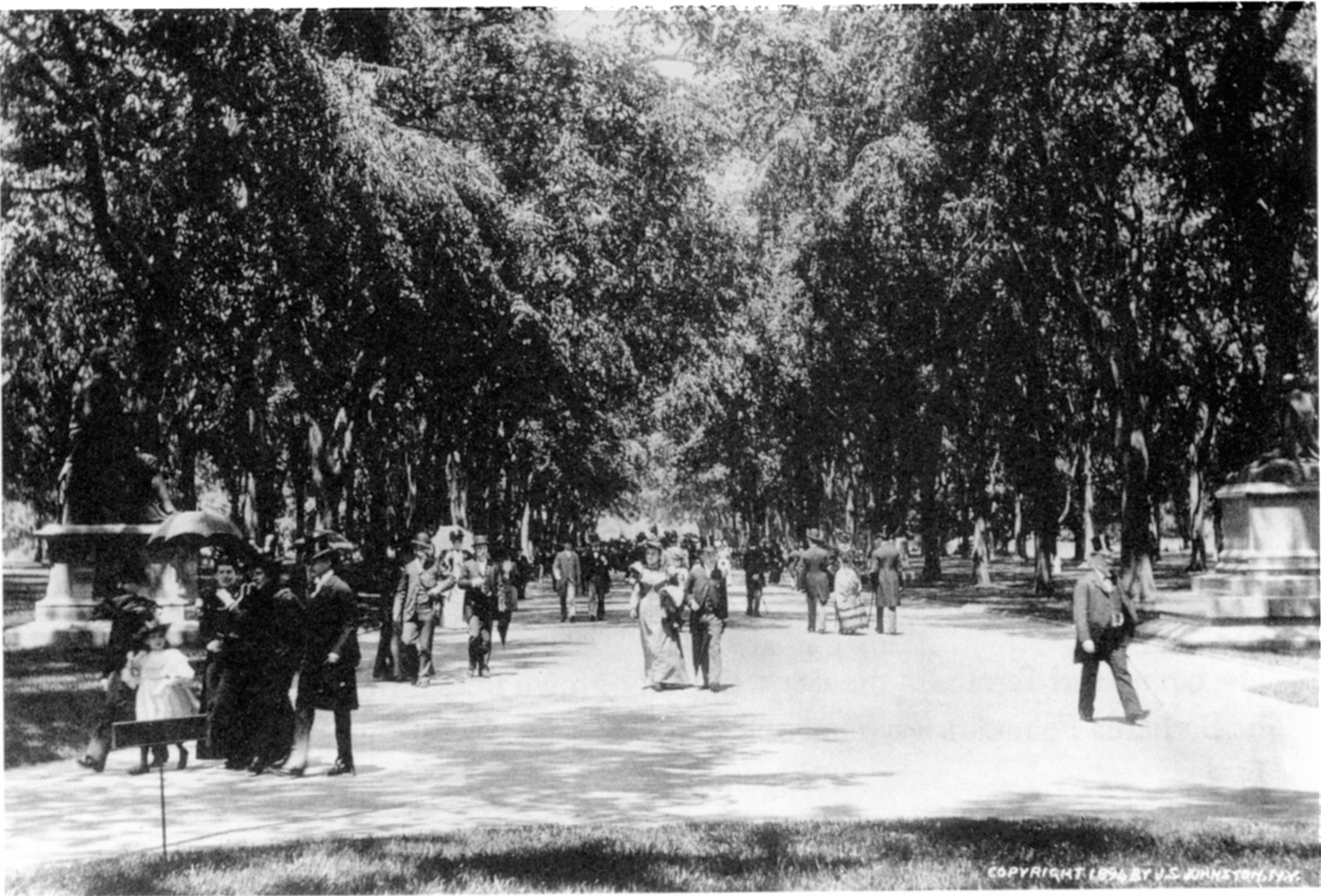

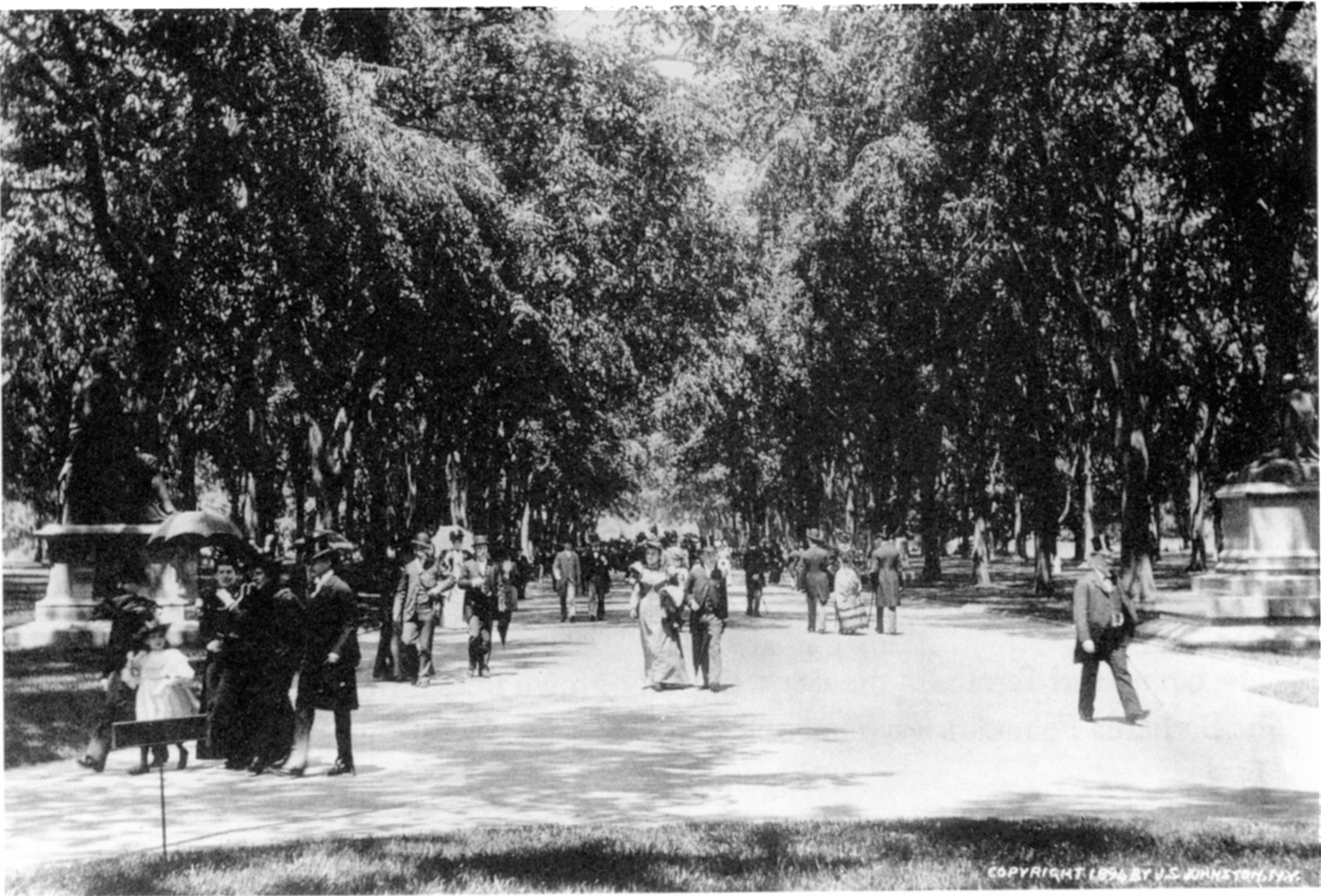

The freshly graded Mall in 1863, shortly after completion with rows of American elm saplings.

The Mall in 1894. The green canopy forms a solid archway over the promenade.

The Terrace in 1863, still under construction.

The completed Terrace in the 1880s, the fully-grown trees forming a solid backdrop. The Bethesda Fountain, a symbol of healing, was added after the end of the Civil War. The gondola is Venetian.

The Terrace in the 1920s, as popular as ever, even though the fountain is not running.

The site of Central Park consisted of rocky outcroppings and swampy lowland. The meadows, woods, and lakes, which Olmsted imagined as a poor-man’s substitute for Adirondack scenery, are entirely man-made.

Winter, 1866. The surroundings, visible through the sparse vegetation, are largely rural. The lake was hurriedly completed and ice-skating quickly became a popular pastime.

Winter, c. 1890. The trees hide the adjacent city, except for the newly built Dakota apartment house.

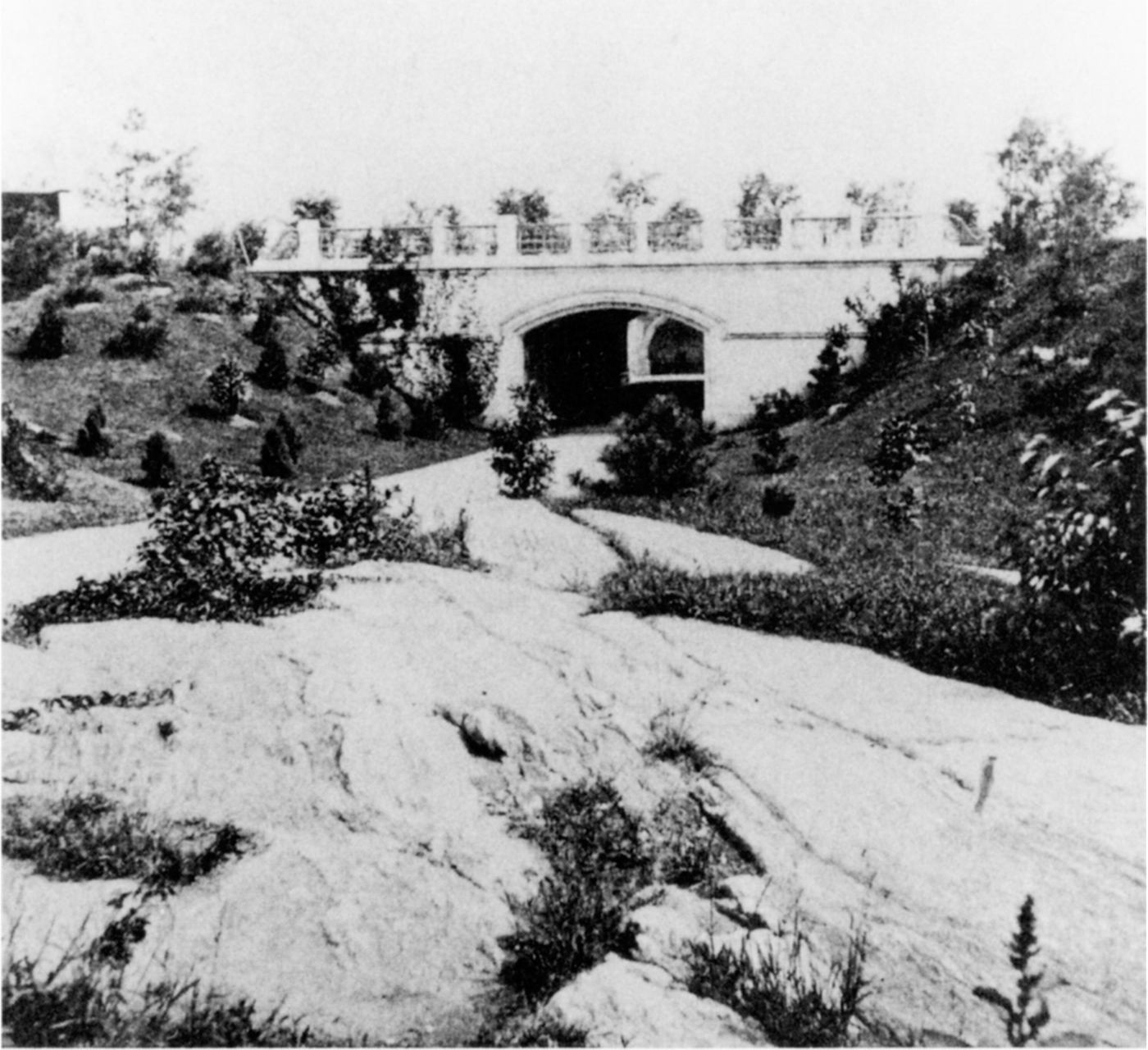

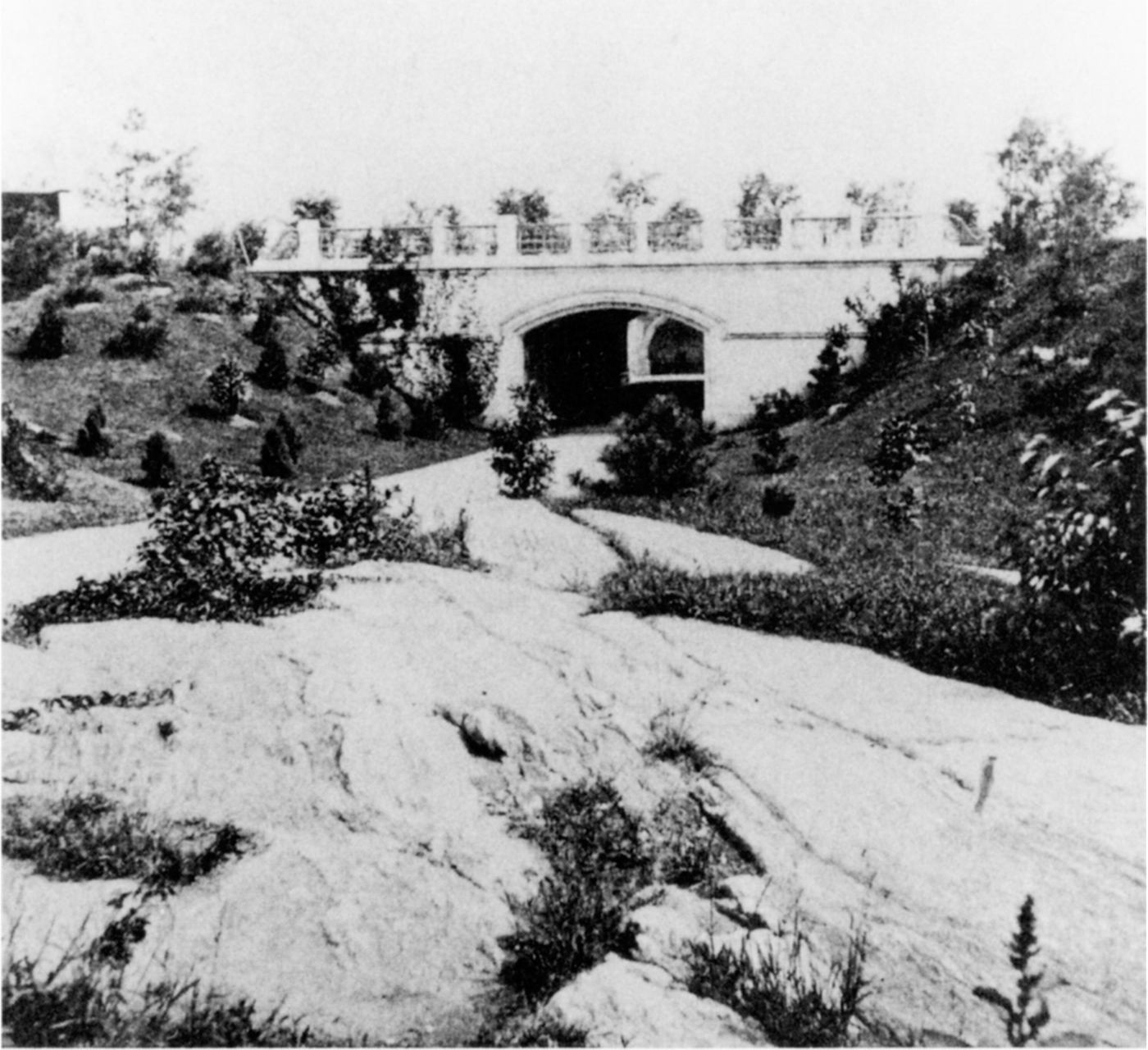

In the early 1860s, the new landscape is still bare. The Marble Arch, which no longer exists, was the chief pedestrian entrance to the Mall.

Some twenty or thirty years later, the arch is beginning to be hidden by the vegetation. Architecture always took second place in Olmsted’s parks.

By the early 1900s, the arcadian illusion is complete. New Yorkers of all ages, classes, and races gather in a meadow.

Lawrenceville School, New Jersey

Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscaping practice included not only public parks, but also civic buildings, suburban subdivisions, private residences, and universities. In 1883, he began designing a new campus for Lawrenceville School.

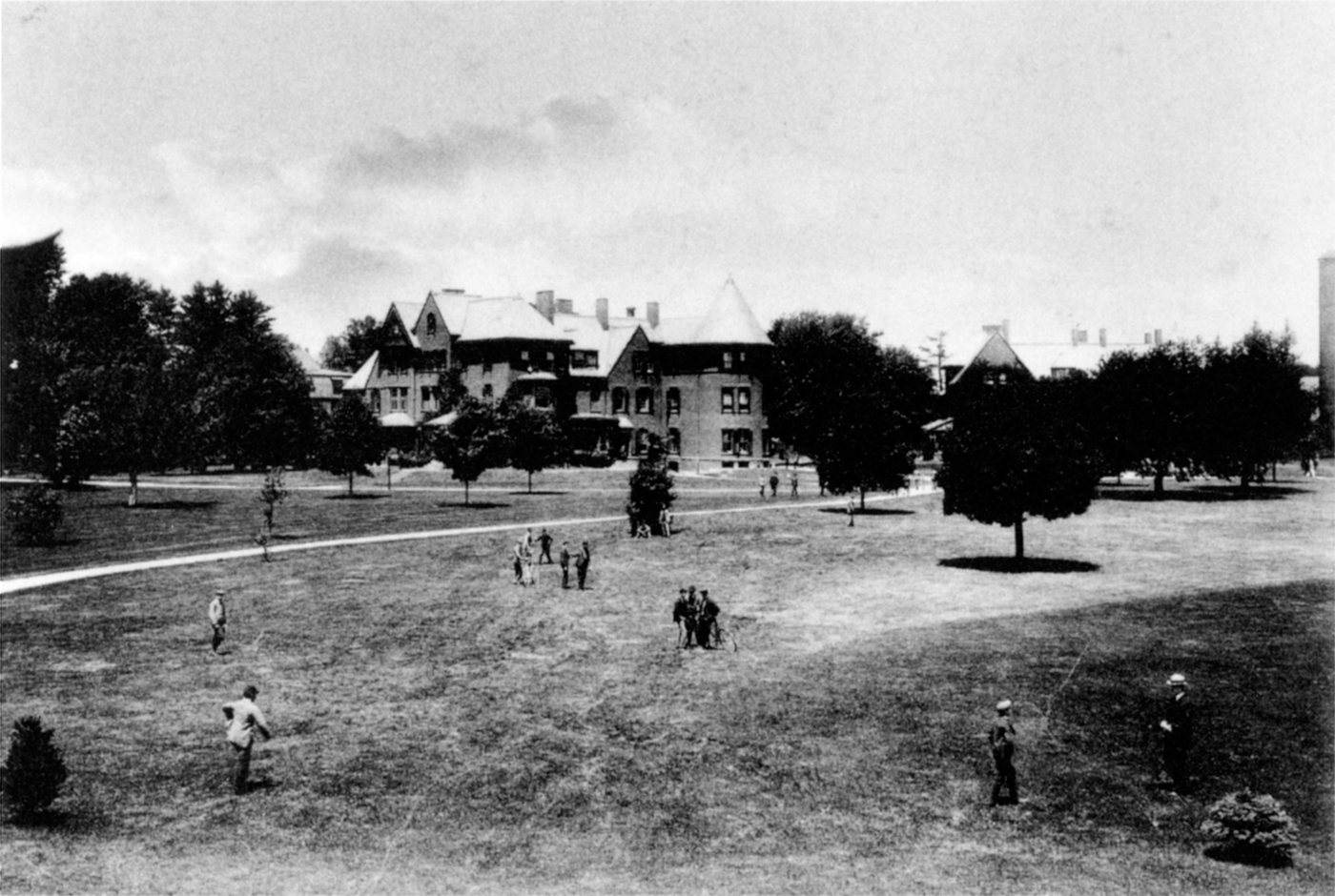

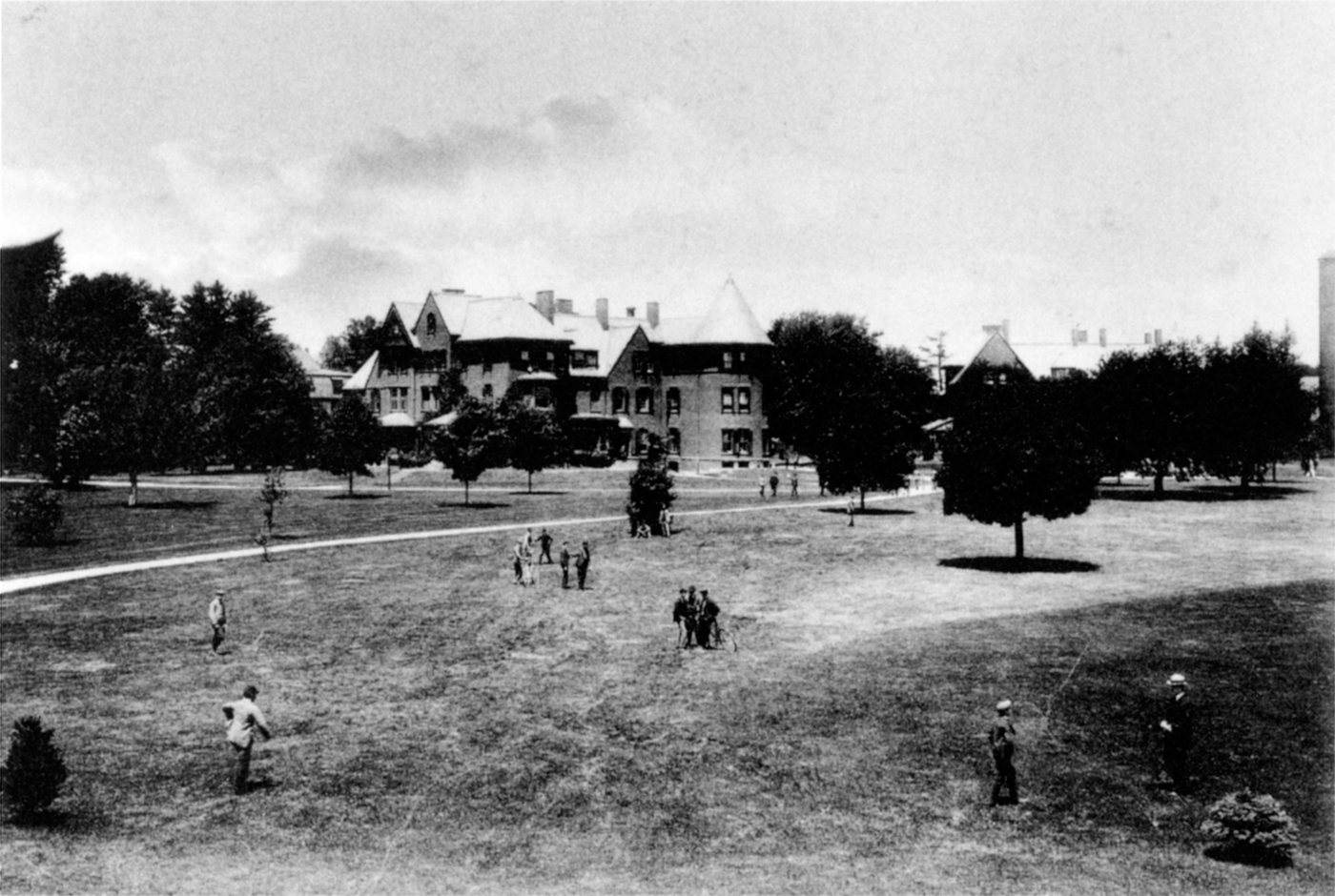

The focus of the school is the Circle, shown here in 1885, shortly after completion. Olmsted’s design intention is hardly visible in this bare landscape. He incorporated a few existing large trees into his design.

This photograph, taken about 1896, shows Olmsted’s vision of a New England village green starting to emerge.

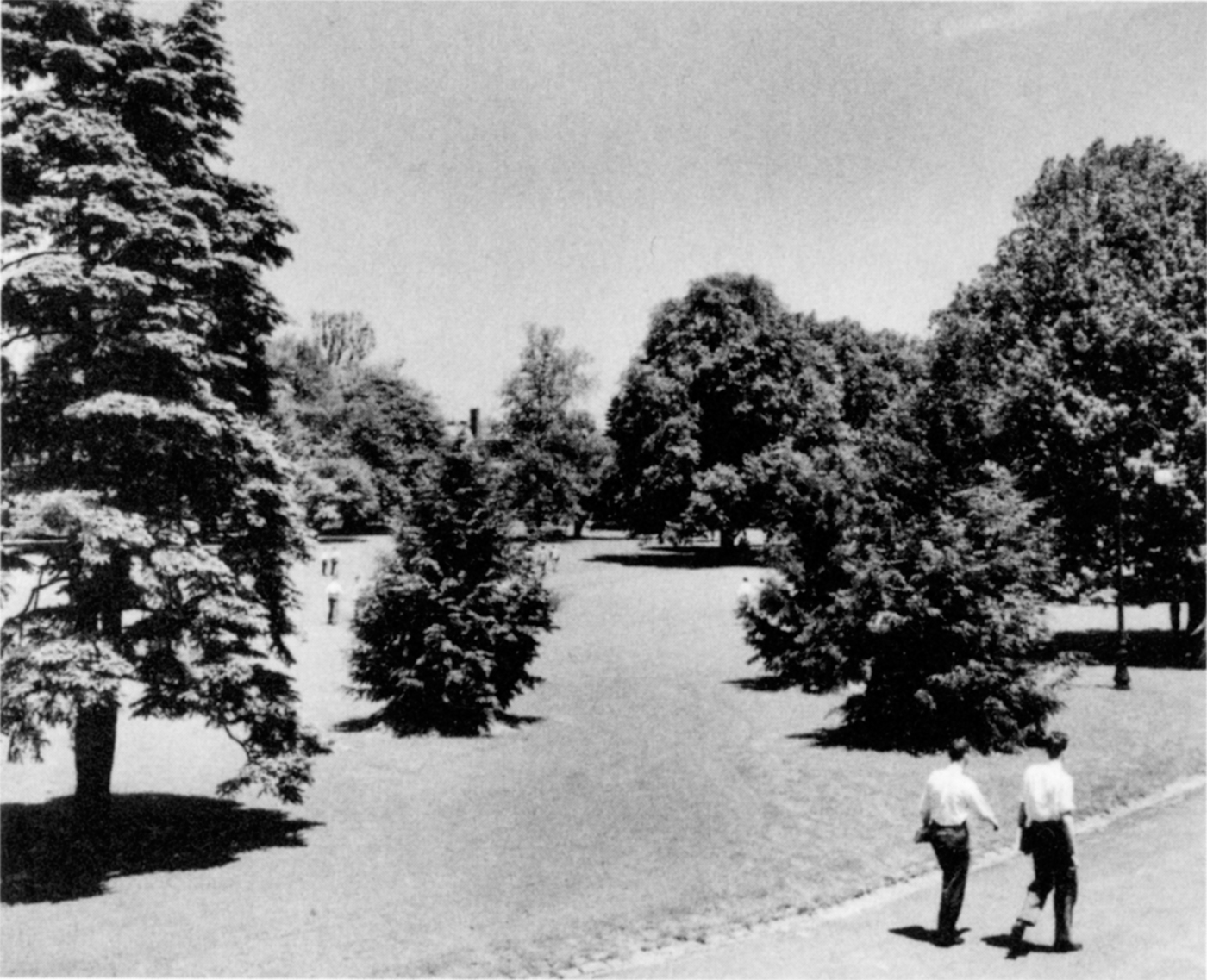

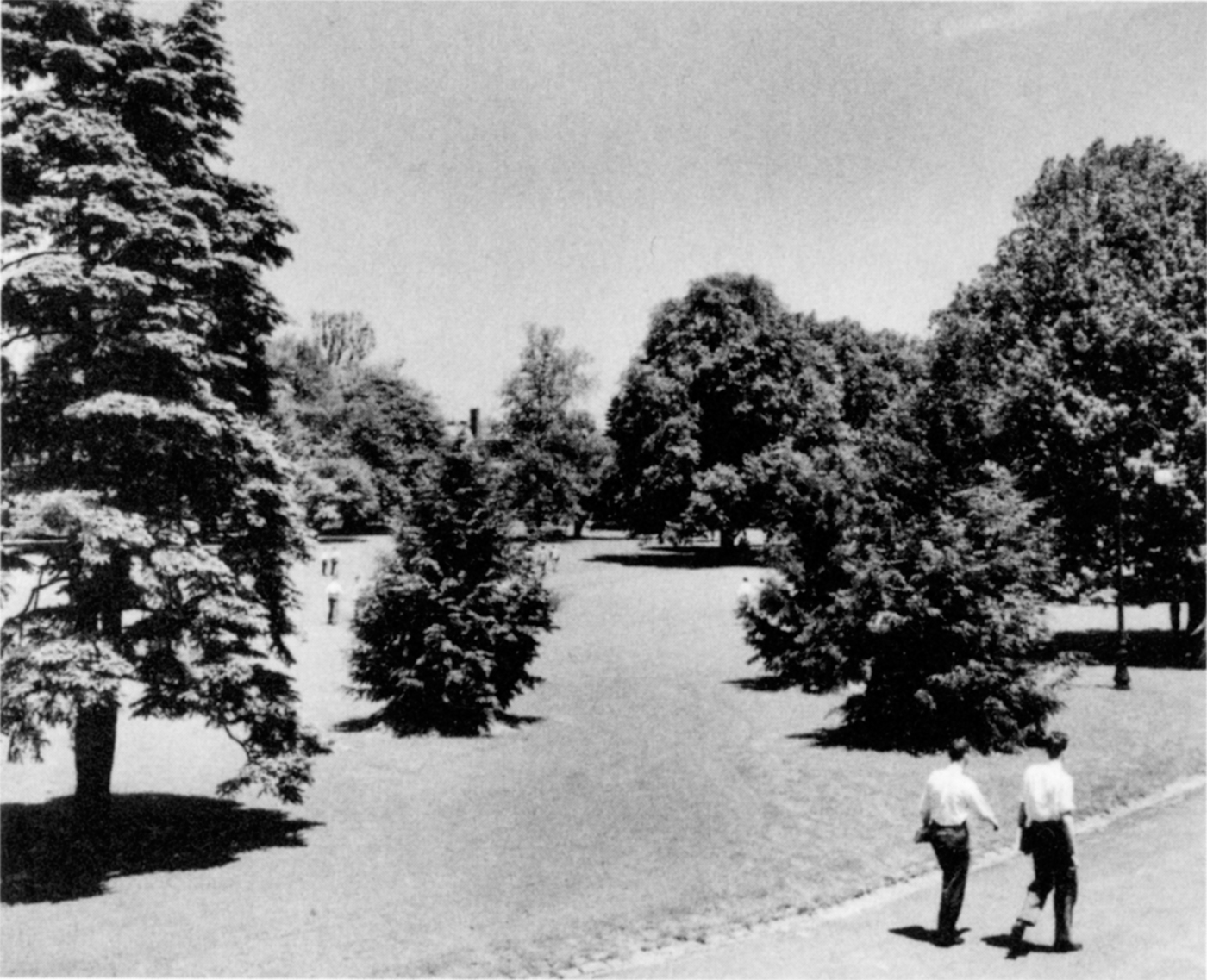

By the 1950s, the school buildings are almost entirely hidden among the trees.