It remains a scholarly commonplace to assert that Victorian sexuality was dominated by an ever-expanding regulation of the body. Even when the rise of the New Woman challenged gender norms, or clandestine but assertive communities organized around shared homosexual identity, the discursive impact of these movements—according to current scholarly consensus—inevitably culminated in, or capitulated to, dominant social forces of discipline and subjugation. This agrees with a concept of subjectivity as the product of cultural encoding rather than an expression of a deep interiority existing prior to structuring principles. This paradigm also insists that subject formation entails subjugation. Jeffrey Weeks details how Victorian preoccupations with strict moral hygiene worked in tandem with increasing state regulation. A bureaucracy of civil servants concerned with monitoring sexuality generated, in Weeks’s words, “intricate methods of administration and management, . . . a flowering of moral anxieties, medical, hygienic, legal and welfarist interventions” with an elitist valence.1 In a pathbreaking study, Peter Stallybrass and Allon White treat the police and Hudson’s Soap as nearly interchangeable agents of “discipline, surveillance, purity”; their work begins with, and expands on, Michel Foucault’s suggestion that social and institutional practices found their typical nineteenth-century expression in the “privileged form [of] Bentham’s Panopticon,” with subjects haplessly policing their own behavior in response to unseen observation.2 Judith Walkowitz’s landmark study Prostitution and Victorian Society (1980) traces a surprising historical bloc of antistatists, advocates of personal rights, police officials, and medical authorities, all agreed on the need to regulate the sexual mores of the poor. Even after the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act (1886), the police enforced the segregation of prostitutes from the laboring poor and promoted “a more rigid standard of sexual stability.”3 Walkowitz ominously concludes that, after the Criminal Law Amendment (1885), “the police had become the missionaries of the new age.”4 For all these scholars—and they are among the very best in the field—the desire to survey and regulate “impurities” in the social body, whether the nonlaboring poor, the “fallen woman,” or unpleasant sewer odors, clearly structures the terrain of mid- and late-Victorian culture and discourse.

The controversy that surrounded Laura Ormiston Chant’s 1894 attempt to close the promenade of the Empire music hall because of prostitution troubles this scholarly consensus.5 Born in 1848, Chant taught, nursed, and worked as assistant manager of a private asylum before she became a noted public lecturer on woman’s suffrage, temperance, and Liberal politics. She was a member of the National Society of Woman’s Suffrage, a merger of various suffrage groups in 1896. Like many women involved in the struggle for suffrage, Chant had ties to social purity movements concerned with regulating sexual behavior. These ties were a legacy of the coalition politics that united moral reformers, medical professionals, and women’s rights activists in the aftermath of the Criminal Law Amendment.6 Chant also had formal ties with the National Vigilance Association, although her efforts to close the Empire promenade were initiated independently from the organization.

That Chant and her cohorts who testified before the London County Council protesting the Empire, the women dubbed by the press “Prudes on Parade,” faced such virulent public disapproval remains something to be explained. Surely a purity reformer’s attempt to bring a disreputable space to order would have been amenable to late-Victorian common sense; Richard Dellamora, for example, details how sexual scandal often called forth professionals, activists, and administrators who agreed on the necessity of monitoring and regulating sexual conduct.7 Controversies in the daily press; the commentary of literary intellectuals like Arthur Symons, George Bernard Shaw, and Clement Scott; the attempt of young Winston Churchill to tear down the partition blocking the Empire’s promenade: all suggest the failure of Chant’s protest to reassert sexual decorum.8

The disparity between our retrospective certainties in regard to fin-desiècle sexual conduct and the libertarian opposition to Chant suggests we have greatly oversimplified late-Victorian gender politics. The controversy stirred by Laura Chant’s attempt to close the Empire promenade quickly shifted from a civic dispute to a crisis over authority. In the words of the London social and theatrical review of current events, the Sketch, the Empire battle was “a great fight . . . waged with a war of words, a battery of correspondence, and a skirmish of sketches.”9 We cannot fully grasp Chant’s reception by the public unless we consider the difficulties female philanthropists faced when they sought municipal reform.

The libertarian ideology that fueled the opposition to Chant also held that vice was best controlled if regulated, and that regulation required that vice remain visible; the worse crimes were those that somehow remained unseen. In the case of the Empire, male professionals dictated that prostitution was best managed under visual surveillance. Business at the promenade was naturalized by many in the literati as obeying a fully respectable aesthetic of order and comely elegance; vice had never looked so good, or so stylish. The calm poise of the aesthete observer further managed, and accordingly neutralized, the dangers of proximate vice and moral misconduct. To the pure Victorian male, all things, it seemed, were pure. The reading public that avidly followed the Empire licensing dispute was alarmed by Chant’s challenge to this disciplinary regime; worse, they feared that, as charity worker, Chant had access to dangerous, “hidden” knowledge concerning prostitutes and the men who consorted with them. The conflict over the Empire quickly became a struggle over credentials: over who had the requisite expertise to utter authoritative statements on sexuality, prostitution, and public amusement. The late-Victorian discourse of regulation and surveillance was, in certain respects, a closed shop, in the hands of almost exclusively male professionals.10 The resistance Laura Ormiston Chant encountered from a coalition of journalists, literary intellectuals, and “free-born Englishmen” results from her entry into the gender-exclusive terrain of Victorian professionalism.

Of course, the growth of the professions, including a new trained, managerial class, rendered it increasingly difficult to reach consensus on such matters as the “nature” of popular amusements. Among so many aspiring experts, who had the proper training to lay claim to the arbitration of propriety and taste? In 1890, four years before Chant’s complaint against the Empire, the London County Council newly instituted the Theatres and Music Halls Committee, with attendant inspectors licensed to impose fines on music halls for violations of public morality and safety regulations. Constantly criticized by music-hall managers, these new inspectors were criticized for their lack of training, for their supposed amateur status.11 J. L. Graydon, manager of the Middlesex Music Hall, suggested these inspectors received too little pay to work impartially: “[I]t is inconceivable that men earning 10s 6d a night . . . could possibly be either competent or have any uniformity of opinion apart from the obvious temptations to blackmail or bribery.”12 Throughout the 1890s, municipal workers, proprietors, and audiences disputed over who was best qualified to supervise popular amusement; relations between music-hall proprietors and municipal authorities remained especially tense.13 In testifying before the London County Council, Chant knew she had assumed authority on contested terrain. “I am quite aware,” she testified, “what a serious charge [I bring] & also what a serious matter it is to state that a woman is a prostitute, but I think before I have finished you will see I have good grounds for making the accusation.”14 Her complaint against the Empire could be vindicated only if she demonstrated expertise on a variety of subjects: popular amusement, prostitution, and civic reform. In the end, Chant’s perceived threat to the Victorian formation of surveillance discredited her, and her vocation as philanthropist received the stigmatized label of amateur labor. Instead of holding her as an expert, the public branded her a “spy,” a meddler too self-interested to receive recognition as a professional.

The Empire Theatre of Varieties opened in 1887 under the management of George Edwardes; prominent in the music hall was a large promenade contiguous to the lounge. A London County Council report estimated that nearly five hundred people, in a hall that normally seated around thirteen hundred, routinely utilized the promenade.15 On October 19, 1894, Laura Ormiston Chant and six others brought a complaint against the Empire music hall before the London County Council, claiming “that the place at night is the habitual resort of prostitutes in pursuit of their traffic, and that portions of the entertainment are most objectionable.”16 Statistics concerning Victorian prostitution notoriously vary, but there is evidence to suggest that Chant’s protest against the Empire promenade was not a simple moral panic. Tracy Davis characterizes the location of the Empire in Leicester Square as a crucial site in what she dubs the “geography of sex”; she notes the hall’s proximity to “thoroughfares of vice,” claiming it was “a vital nexus of West End immorality involving prostitutes, alcohol, variety theaters, supper clubs, dancing halls, and gambling houses.”17 In 1892, noted music-hall proprietor John Hollingshead claimed that “the sweepings of Hamburg and the low Countries own the right of way” in Leicester Square and designated the area as “the prowling place of demireps.”18 Accounts of the Empire that acknowledge the conspicuous presence of prostitutes in the promenade are too numerous to mention.19 Even a staunch defender of the Empire confessed, “Every sane man knew vice had been prominent in the Empire promenade.”20 When the London County Council temporarily closed the promenade in support of Chant’s suit, casual reports remarked on the migration of prostitutes to the nearby Alhambra variety theater. The Sketch editorialist noted sardonically, “The daughters of the Empire seem to have been lifted up like the prince in the ‘Arabian Nights Tales,’ and dumped down in the Alhambra,” adding that, “you could not move an inch without hearing remarks about the humour, one might say absurdity, of such a state of things.”21 Although celebrated literati Arthur Symons and Theodore Wratislaw defended the Empire against Chant, both depicted erotic encounters at the Empire in their poetry that belied the accounts they presented to the public in the media.22 The testimony of literary intellectuals disdained any empirical account of the halls in favor of an aestheticized view of music hall as pure spectacle.

Chant received complaints in early 1894 from an anonymous pair of American men about being “continuously accosted by night and solicited by women” when they visited the Empire—at Chant’s own recommendation—to hear Albert Chevalier’s coster songs.23 Chant, accompanied by fellow suffragette Lady Henry Somerset, conducted her own investigation of the Empire. She made five visits to the music hall and paid more care to her physical appearance, clothing, and deportment on each occasion. She claimed that “on the first three occasions of her visits she dressed quietly, and on the fourth and fifth occasions gaily—that was to say she wore her prettiest evening dress in order that she might get her information more readily.”24

Chant’s effort to change her wardrobe to suit her surroundings must be read as a practical concession to the space, based on an interpretation of the Empire as a homosocial space and a launch pad for predatory males. Accounts of the Empire uniformly assert that the music hall was, in J. B. Booth’s words, “as it justly boasted, an Englishmen’s club.”25 A prime example of the “variety theater” entertainment that was to replace more plebian halls, the Empire was a gathering place for men of leisure. The music hall permitted the divergent vectors of English colonial expansion to converge in a privileged site of leisure suggested by the hall’s very name. As Booth puts it: “Britishers prospecting in the Klondyke, shooting in jungles, tea planting in Ceylon, wherever they gathered in cities in Africa, Asia and America would bid one another goodbye with a ‘See you at Empire one day when we’re back in town.’”26 The Empire offered entertainment at a price slightly prohibitive for working-class patrons, although working-class audiences—besides the estimated three thousand workers directly affected by the hall’s closing—were among the most vociferous critics of Chant’s reform.27 The Empire, however, remained within the buying power of middle-class men who desired to mingle with an upper-class demimonde of men and women.28

Theater historian W. Macqueen-Pope stresses the importance of the Empire promenade to men in search of illicit “attractions”: “And the attraction was the cream of the frail beauties of the town. . . . middle-class young men rejoiced to pay their five shillings . . . to have the daring and Bohemian thrill of a night spent in the Empire Promenade, to watch the wicked ladies as they floated—none of them seemed to walk—to and fro; wonderful women wonderfully dressed, . . . overwhelmingly alluring in their known ‘naughtiness.’”29 Stage entertainment gained the extra frisson of sexual possibility because of the Empire’s promenade. The women that Macqueen-Pope surveys here are canny entrepreneurs “quick in summing up anyone who meant real business.” Young men could boast of an encounter with them “for weeks and be regarded by their less reckless companions as desperate blades.” Macqueen-Pope covers a utopian world of male desire with the patina of nostalgia, admiring the opportunity the hall offered middle-class men to solicit women from a sophisticated demimonde who, even if they rebuffed the rake, nonetheless augmented his cultural capital. The Empire, in this reading, allowed men the chance to interact with “dangerous women” with “very little harm.” Martha Vicinus observes that the music-hall environment appealed to male audiences chiefly for these possibilities: “[F]or many young men, cooped up in an all-male office or warehouse all day, close proximity of women, drink and smoke made a giddy and inviting atmosphere of women that broke down their natural shyness and difficulty in speaking to women of their own class.”30 Macqueen-Pope frames the Empire as a masculine haunt, and his “wicked women” primarily signify aristocratic leisure. The same point is underscored in another account of the hall, in which Macqueen-Pope asserts, “[T]he women of the Empire were the aristocrats of their ‘profession.’”31 The Empire offered aspiring middle-class men everything that Vicinus observes and more: an imaginative participation in aristocratic culture.32

Chant’s testimony before the London County Council challenged the voyeurism represented by these accounts. She displayed the relatively new mobility of middle-class women in urban spaces, exerting control over the Empire as an authoritative observer. In a mock flourish, George Bernard Shaw praised Chant’s individual skill and considerable acumen in presenting her case: “You can’t have a better example of democracy than the Empire case. Here is Mrs. Chant . . . and she flounces in and floors the whole County Council.”33 Shaw’s praise of a strong individual, however, overlooks the respect for collectivist politics, of a sort that Shaw championed, that clearly motivated Chant’s protest. Further, her argumentative skill was not a fluke of temperament or a sign of entrepreneurial zeal. She looked to the London County Council, as many municipal reformers of the period did, because she wished to intervene in the council’s general project, the administration and rationalization of a sprawling urban culture. Like many of her peers in reform work, and Shaw himself, Chant looked anxiously to the state, or centralized authority, to execute genuine, far-reaching reforms.34 As self-declared expert, Chant attempted in her testimony before the council to influence fellow administrators, to share a specialist’s knowledge with the municipal body regulating London’s cultural life.

Chant’s deposition features a careful reading of the Empire promenade, locating signs of the “fallen woman” and carefully organizing them into a narrative. In her words:

There were very few persons in the promenade, but bye-and-bye, after nine o’clock, I noticed to my astonishment, numbers of young women coming alone, most of them very much painted, and all of them more or less gaudily dressed, numbers of young and attractive women. . . . [T]hey did not come into the stalls, but either sat on the lounge sofas or walked up and down the promenade or took up a position at the top of the stairs and watched particularly and eagerly who came out of the stalls and walked up and down the promenade. I noticed that in no case were any of these young women accompanied by gentlemen or accompanied by others, except of their own type.35

Amid these suspicious-looking women, Chant noticed “a middle-aged woman” who introduced a gentleman to the young women. She testified, “I noticed she came and tapped him on the shoulder and I followed them. She introduced him to two very pretty girls who were seated on a lounge . . . one of them very much painted and beautifully dressed. . . . I saw this man and this girl go off together, . . . an attendant call a hansom for them.”36 Afraid that quietly dressed women draw attention to themselves in the Empire (she overheard an Empire attendant warning one woman, “You had better mind how you behave to-night as there are strangers round”), Chant secured her evidence by taking up a “disguise.” As an outsider in male spaces, Chant dressed “gaudily” enough to “pass” at the Empire. Much was made during the hearings of the unintended effects of this subterfuge, since Chant herself was approached in an inappropriate manner by a gentleman when she assumed her “disguise.”37

Chant relied more on her prior work as a philanthropist than on her undercover work on the promenade to bolster her account. She repeatedly referred the council to inside knowledge she had gathered from her informants among the women on the promenade.38 These women disclosed to Chant that the Empire “is the best place where they can carry on their trade. One and another have told me they could not do without the Empire.”39 She reiterated that “[t]heir testimony, absolutely frankly and candidly given, is that they go to the Empire . . . because they . . . can make better bargains.” Chant’s observation of women in the Empire promenade was not her sole encounter with “fallen” women; she regularly brought prostitutes into her home whom she met on the streets and who expressed the desire to reform.40

Chant’s testimony, and her rescue work on the streets, suggested what many men feared: that female philanthropists “saw more than men.”41 As Martha Vicinus describes, female philanthropists exerted considerable authority in urban spaces: “[T]he streets of the slums, away from upper-class men’s eyes were theirs.”42 Chant’s deposition places the hidden work of the prostitute on display, and this ability underwrites a tremendous authority for her among members of her own class. While no booster for Chant, the editor of To-Day grudgingly respected her achieved expertise in regard to the social consequences of the trade in women: “[A]fter twenty-years of rescue work, Mrs. Chant knows more of these things than many men about town, and when she spoke of them, there was the ring of truth and sincerity in every word.”43

Chant’s charity work played into the dominant cultural imperative for members of the middle class to understand and control the sexuality of working-class women. Elizabeth Langland, following the work of Nancy Armstrong, Catherine Hall, and Leonore Davidoff, stresses that middle-class women “cooperated and participated with men in achieving middle-class control though the management of the lower class.”44 Insofar as Chant made the secret machinations of prostitution more visible, and thereby subject to control, her work supported a social discipline enforced by panoptic surveillance. However, Chant’s interviews with the urban poor put an emphasis on unmediated contact, not specular control. Rather than the impersonal regulation of bodies, Chant sought to achieve interpersonal relation with the urban poor, and, moreover, did so in a manner that disturbed exclusive male control of London streets.45 Her venture into the promenade on behalf of “the women of England”46 disturbed the otherwise orderly production of male spectatorship, and the male gaze, at the Empire.

That Chant did not play a simple version of the surveillance game is best demonstrated by her later responses to the press, in which she targeted wealthy men as the real malefactors at the Empire. Answering the charge that closing the Empire promenade would force prostitutes into nearby streets, Chant asserted: “It is not the streets which furnish those who fill the ranks of fallen women. The poor souls fall at such places as the Empire and then parade the streets afterwards.”47 In a paternalist fashion, Chant denied agency to working-class women; she did so, however, for tactical reasons. Casting the working woman as victim made the Empire’s more affluent patrons seem the true and conscious culprits in the social scenario of vice.48

Chant responded to the complaint that “the working men of England object to have their amusements interfered with” by asserting that “working men . . . will admit that the Empire is no resort of theirs.”49 This proved a presumptuous claim about the Empire’s audience, but it followed from her general suspicion of the Empire’s more privileged habitués. Chant’s class antagonism was likely informed by the “Maiden Tribute” controversy, the Pall Mall Gazette’s inflammatory account of aristocratic men seducing young working-class girls. Her reading of the Empire is similarly shaped by melodramatic convention, with images of innocent women victimized by jaded, remorseless, and essentially villainous rakes. Melodrama explained the Empire for Chant, although the prostitutes on the promenade represented a relatively affluent, and minority, demimonde.50

The reformer was resolute in finding class enemies against her reform even after the Empire controversy faded; she detected the conspiracy of moneyed men behind the newly elected, more centrist, London County Council. The new council, she charged, undermined the previous council’s reform of the Empire because its election had been made possible “mainly by the money of two classes, the wealthy profligates and the gamblers.”51 Chant’s reading of hidden interests protecting the promenade sets the Empire’s responsible bourgeois and working-class patrons against an irresponsible bourgeois (“gamblers”) and the degenerate rich. As the controversy played out, the Empire’s middle-class patrons increasingly disregarded Chant’s insistence that social divisions and inequity characterized the hall’s audience; they remained comfortable participating, even if only vicariously, in the “spectacular” diversions offered by the pleasure palace.

Laura Chant’s belief in a conspiracy of privilege affects her reading of performance at the Empire. Her major criticism of the Empire centers, not on the ballet or the “living pictures” performed there, but on the affluent men who consumed the entertainments. She charges that jaded sensation-seekers sustained the “degrading” conventions of ballet costume. In her words, “[Ballet dancers] cannot see that the absence of clothing is an offense against their own self-respect. They do not realize that they are exhibited well-nigh undressed for the men in the lounge, men so used up they could not be attracted by a less sensational form of spectacle.”52 Chant anticipates later critics of fin-de-siècle ballet such as Amy Koritz, who details how English ballet privileged the male gaze, and Tracy Davis, who examines how ballet dancing was specially coded as libidinal fare for men.53 Chant’s pronouncements carefully exempt the working class from the male gaze, imagining these patrons as her potential allies against the “men in the lounge.”

Chant’s deposition against the Empire amounted to savvy self-promotion, if not calculated self-fashioning; she deftly presented herself as a daring, yet trustworthy, social investigator. She pointedly demonstrated her credentials and her power over complicated areas of experience. Her rhetoric transforms the space of the promenade into a special field, of which she claims to possess esoteric knowledge that proves the competence of her judgment and acumen, as well as her charisma. The testimony amounts to a compelling account of the deep, mysterious forces behind the confusing blur of appearances that constituted the spectacle of the promenade. Chant’s description of the space competed with other powerful, purposely competitive narratives for popular approval. Throughout October 1894, London newspapers circulated the dispute over how to read the Empire, with the Daily Telegraph offering its editorial and letter pages to the controversy for almost the entire month.54 Numerous letter writers marshaled English common sense against the perceived extremity and moral fervor of Chant’s reform. H. A. Bulley’s letter in the Pall Mall Gazette (the Gazette’s own editorial quoted Cromwell against the puritanism of the social purity workers) dubs the purity crusade “an organized Puritan conspiracy against the liberties of the English people.”55 A correspondent in the London Times, signed “Freedom,” complains about female government: “If the Vigilance Society is to rule over our lives, and constitute itself an English Police des Moeurs, by all means let us have an Anti-Vigilance Society with the Englishman’s motto, ‘Imperium et Libertas.’”56 As a writer to the Pall Mall Gazette inquires, “Shall Britons be ‘slaves’ now more than they used to be?”57

Meanwhile the literati began to weigh in on the issue. In the Saturday Review, Arthur Symons defended “human nature” against legal fetters: “Does any one really think that by closing, not the Empire alone, but every music hall in London, there will be a single virtuous man the more? . . . In the normal man and woman there are certain instincts, which demand satisfaction, and which if merely restrained and fettered by law, are certain by some means or other to find that satisfaction.”58 The poet’s assertive claim for the cause of the Empire also demonstrates the ease with which an Enlightenment-style demand for the respect of individual rights could underwrite male license. Arguments that stressed the inviolability of “human nature” had the practical effect of keeping the Empire available for heterosexual cruising. Such libertarian sentiment does not invalidate the argument that Foucauldian discipline dominated fin-de-siècle sexuality; laissez-faire attitudes toward personal morality could nonetheless coexist with an anxious administration of private conduct.

Libertarian support for the maintenance of the Empire coexisted with a taste for the beautiful and orderly. In like manner, the disciplinary gaze is indistinguishable from the male gaze. The Empire offered itself as a ready solution to the “social evil” of prostitution, and accounts like Symons’s eagerly took up this cause. With the London County Council’s official regulation of the Empire, the music hall appeared to offer what many medical professionals hoped for: the toleration of prostitution alongside its regulation, with a minimum of government involvement.59 As a licensed music hall with respectable patrons, the Empire allowed the “safe” harboring of prostitutes, providing a space where prostitution received moderate supervision, rather than overt repression or strict regulation. Chant’s protest competed with a political rhetoric that found overt intervention in sexuality “unBritish.” Instead the liberties of the true-born English gentleman, secured by historical precedent against meddling women, were maintained. Chant challenged a consensus that believed prostitution was neutralized if it remained a spectacle.

Chant’s efforts to establish herself as an authority on prostitution also struck at popular conceptions concerning professional character. A debate over what constituted a true professional emerged in the press, elicited by a consideration of the Empire case. A correspondent in the Daily Telegraph asserts that Chant and “those who push themselves forward into the administration of licensing laws” had “no sort of special training as a guarantee either of judicial fairness or practical experience.”60 T. Werle offers a specific complaint regarding Chant’s qualifications: “Will someone be good enough to tell me why it is that the evidence of any volunteer as to the propriety of the entertainments given should be, as seems to be the case, accepted?”61 Werle asserts that “when a witness represents some performance not to be in good taste one may well enquire why a mere self-accredited arbiter elegantiarum is allowed to be regarded as a judge in the matter”; he presumes that Chant’s arguments can be trumped by the making of a credential check. The Daily Telegraph’s editorial raises questions about the relative competence of female philanthropists compared to already recognized authorities. The editors insist, “The public has a perfect right to ask the question—of what use are the paid inspectors whom the County Council employ to see that music halls and other haunts of recreation are well conducted if their reports are to be thrown on one side?”62 The editorial laments that “amateurs ‘on the prowl’ are listened to while the professional advisors of the Council are thrown overboard.” The Telegraph attempts to naturalize what Chris Waters observes was a contested point in licensing disputes throughout the decade: the expertise of the “paid inspectors” of the London County Council (LCC). Here, the supposed disinterest of these men is evoked as a counter to Chant’s own claims of authority.

The same Telegraph editorial expresses the fear that social surveillance by the “prudes” would lead, by way of the slippery slope, to the ritualized misrule of “petticoat government.” Hence, the next, inevitable victims of Chant’s vigilante efforts would be those authorized to keep public assemblies controlled and orderly, the police. As the next object of Chant’s surveillance, the police might be hindered from performing their sworn duty to uphold civic order. In the editorialist’s opinion, “It requires very real courage for an officer to come forward and boldly speak up for the hall when he knows that the spies of Vigilance Societies may, in consequence, constantly dog his footsteps in the hope of detecting him in the great unpardonable sin for which Scotland-yard extends no pardon—drinking on duty.” The Daily Telegraph intimates that the effort to close the Empire promenade would lead to unseemly reversals, with capable authorities now under the watch of amateurs. Let men police men, the editorial suggests. Fears of such inversions, of unmanned policemen and masculinized “prudes,” elicited letters like that of “An Ex-Police Inspector,” who argues that professional police should take jurisdiction of the Empire away from the LCC.63

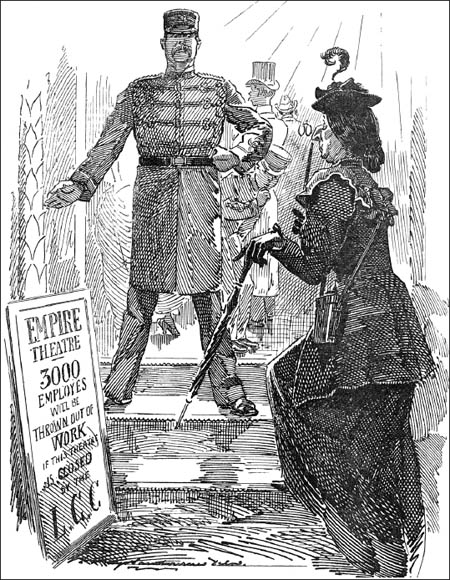

The struggle between “unauthorized” reformers and recognized authorities, between those who made dubious attempts to pry into sexual practice and those truly capable of monitoring indecorous behavior, was highlighted in the many caricatures spawned by the controversy.64 One of the most notable, Punch’s sketch “Mrs. Prowlina Pry.—‘I Hope I Don’t Intrude’” represents Laura Chant as an unwanted intrusion in a safe, regulated space under the guard of legitimate authorities (figure 3).65 The caricature depicts Chant discouraged—or barred—from entering a place where masculine pleasures are already sought and found in relative tranquility. The Empire is portrayed as guarded by a stout, prepossessing doorman, who protects the men (and a solitary woman, whose bare ankle the viewer can make out behind and between the legs of the doorman) from Chant. The caricature portrays Chant as an unattractive spinster, in keeping with the iconographic war against public women that extended, as Lisa Tickner documents in The Spectacle of Women, to the representation of Edwardian suffragettes.66 The doorman’s hand draws attention to a sign reminding the onlooker that “3000 employes will be thrown out of work if this theatre is closed by the L.C.C.”; however, the sketch itself makes an implicit statement. The Empire is depicted as a bright, well-lit place in contrast to the dark, dour, “fancy dress” clothing of Chant. Further, the doorman’s visible alarm at Chant’s attempted entry suggests she is an unwanted presence, an interloper among the Empire’s regular clientele. The caricature brings home to Punch’s readers the ludicrous nature of Chant’s claims to be a disinterested investigator; this woman with drab hat and opera glasses could never spy on the Empire without drawing attention to herself. The shape of the feather on Chant’s hat further visually underscores the dubious nature of Chant’s police action. Above all, the sketch accumulates visual cues that “demonstrate” the incapacity of women, particularly this woman, to escape the confines of their biology. This “grotesque” figure can never hope to attain the universal vantage point occupied by true professionals. Since it is nearly impossible to locate a visual repertoire that might figure a woman as a professional, the sketch artist takes an easy way out. He presents her instead as a ludicrous meddler, attempting to bring order to an already decorous space. In the process, the sketch transforms the Empire into something of a paradox: a naturally tidy space that is at the same time a testament to the virtuous principles of sage management.

The sketch also turns the debate into a matter of taste and a concern for the body. The two concepts are conjoined, of course, in aesthetic discourse. As Terry Eagleton observes in The Ideology of the Aesthetic, aesthetic discourse coordinates a long history of scattered philosophic reflection in the West on relations between mind and body. Aesthetics formalizes the correspondence between sense impressions, the stuff of lived particulars, and the supposed universal truths arrived at through reasoning.67 Aestheticism privileges an ideal, harmonious relation between the mind and the body of absolute equanimity and order. Such premises authorize certain body images to stand in for the beautiful, as agreed-on images of order and decorum. These body images exude good taste. The Punch caricature broadcasts the message that Chant has the wrong body for her line of work. The reformer’s “rude” and unshapely body disqualifies her from assuming the role of taste arbiter, or spokesperson for ethics and decorum. The caricature sanctions skepticism toward the compatibility of reason, or taste, with inappropriate female figures. The humor depends on a hard kernel of ideology: the dogmatic belief that dubious bodies produce questionable taste. With the wrong figure, and gender, Chant lacks the requisite authority to undertake a police action on behalf of the state; rude figures are relegated to vigilante status. They lack the required credentials for social work.

Figure 3. Spies are not experts: “Mrs. Prowlina Pry.” From Punch, October 27, 1894, 194.

The sketch, then, visualizes an argument about Chant’s sensibility, or lack of it; her body conclusively proves her failed taste. This failure occurs not solely on account of her gender, but remains tied to corporeal matters. Chant’s assumed lack of fashion sense and the features of her face: both disrupt the achieved harmony, and awesome self-sufficiency, of the Empire. Amid the measured elegance of these surrounding, the reformer is visualized as a drastic contrast. Punch comes dangerously close to suggesting that only the beautiful can be reasonable and thus contribute to a discourse about the commonweal, and that only the attractive have good taste.

The accompanying poem, “Mrs. Prowlina Pry,” suggests the hazards of careless meddling by aesthetic misfits in civic matters; “Reformers must not act like gutter-boys / Who rake up mud, stir each malodorous puddle,” Punch warns.68 The verse also emphasizes the dangers of emptying “vice” from a properly regulated space into areas where it can spread unmolested. Reformers grub around a safe haven “[u]ntil the foul infection loads the gale, / And pestilence stalks boldly in the high-way.” The lampoon instills a fear of unregulated prostitution: “What if, free, / They [prostitutes] carry foul contagion through a nation?” The poem threatens contagion, associating Chant’s reform with the assertiveness of the New Woman: “Petticoat-government, PROWLINA PRY, / Of this peculiar sort will scarcely suit us.” The poem displaces anxieties about Chant’s reform into a general aversion toward women who exert improper authority.

Above all, Punch’s caricature suggests the Empire is an area already under expert control. “Another Englishman” makes the confident claim in the Telegraph that the Empire, as an “intelligent and liberal provider of innocent recreation for the metropolitan public,” is “so admirably conducted as to be a model of what such establishments should be.”69 Praise for the Empire takes a decidedly Foucauldian tone in a Daily Telegraph editorial, which lauds “the acumen with which the commissioners of the Empire and cognate places of entertainment ‘spot’ or detect women who are likely to be troublesome in public.”70 Another Telegraph editorial extols the Empire for its “efficient control and supervision” of indecorous behavior.71 The Music Hall and Theatre Review claims that the Empire was “under the closest control and the strictest surveillance of the authorities.”72 Such statements echo Michel Foucault’s assertion that in the disciplinary society “visibility is a trap.”73 Allowing prostitution in a well-regulated space is preferable to placing it out of sight, in urban areas where contagion spreads unchecked.

In practice, closing the promenade would mean the women of the Empire would no longer be contained within a specific space or visual field. The imagined escape of the demimonde from surveillance elicited some very anxious commentary. “The suppression of the promenade,” the Telegraph warns, will create a “howling wilderness of brazen-face soliciting women and male profligates of every grade, and ere long we may have to hear of nightly police raids on illicit dens of vice rivaling the depravity of the old night-houses of the West-end”—referring to haunts such as the Coal Hole, patronized by aristocratic “rakes” in the 1850s.74 Fears were raised of an unholy and destabilizing alliance among bold women; there was also anxiety about the promiscuous mingling of men of “every grade.” “What is the pollution of the three-shilling promenade compared to the omnipresent microbe of depraved sexuality in Piccadilly,” the Sketch wonders.75 The Lancet asks, “Is it the least likely to suppress the ‘strange woman’ to turn her from all popular places of amusement and relegate her to the streets?”76 Would she not, the paper warns, “be found more frequently and dangerously in the way there [in the streets] than elsewhere?” Suppressing the Empire would transfer vice from a safe zone of surveillance into spaces beyond police control, stretching regulatory apparatus beyond their effective bounds.

The dispute over the Empire encouraged patrons to construct their own private ethnographies to counter Chant’s informants at the promenade. In one of the most intriguing reactions to the controversy, “A Londoner” turned to the authority of the prostitute herself. “A Londoner’s” correspondence to the Telegraph utilizes an interview with a prostitute to uncover the real story of the Empire. The writer goes to considerable length to verify the authenticity of the account, and displays the anxiety over authorization that Chant’s protest provoked:

As a guarantee of my good faith, I enclose my card, and I offer you my positive assurance that I have only set down, as nearly as possible from notes taken immediately after our talk, the views she herself expressed, with much intelligences, and in moderate but forcible terms. She said, in effect—and I might almost say in the precise language I am recording—the following; and she added that if the managers of the Empire cared to produce her as a witness, she would report before any body of officials all that she stated to me.77

The account begins with the assertion, “I am a freeborn Englishwoman, and I claim the right to live what life I please so long as I behave myself.” Such claims take their place alongside the assertions of individual liberty that proved a focal point in the Empire dispute. This “Englishwoman” declares that individual liberty has priority over “any social reformer, in petticoats, in trousers, or in divided skirt.” The congruence between the laissez-faire individualism of the “freeborn Englishwoman” and her chronicler should urge a reader’s caution: if “A Londoner’s” interview enables a voice from the margins, the anonymous prostitute uses the opportunity to speak on patriarchy’s behalf.

Contrary to Chant’s depiction of the Empire, the interview presents the promenade as a zone of female autonomy. While Chant staged the Empire promenade as a melodrama—with virtue despoiled by callous rakes—“A Londoner’s” account cajoles its male readership. The “Englishwoman” he interviews asserts her moral superiority over female philanthropists, boasting: “I don’t go about peeping and prying after nastiness and feed my imagination on foul stuff. . . . I should like to ask the lady who pretends to have seen such a lot—and yet she is so innocent!—how she knows that the ladies she saw in that place were there for the purpose of meeting gentlemen.” Again, the accusations focus on the concept of expertise, or the lack of it: Chant is charged with reading the Empire badly while pretending to “see” a great deal. “Englishwoman” alleges that Chant makes the obvious mistake of the amateur: she cannot rend the veil of appearance and make genuine distinctions between professionals with status and a lower-class labor force. Chant is criticized for being unable to recognize the telling differences between “the common street-walkers who make Piccadilly circus hideous” and the Empire prostitute: a difference that matters, it seems, to middle-class men. Chant’s lack of discrimination weakens her reading of the Empire and, by implication, her interpretation of other civic assemblies. The ability to recognize these distinctions authorizes “Englishwoman” at Chant’s expense. Logically, she concludes, “I am a better judge of what is going on in the world than Mrs. Ormiston Chant.”

Finally, the “interview” reveals its genuine purpose: to impugn Chant’s motivation as reformer. As the Englishwoman testifies, “[I]t is my belief that Mrs. Ormiston Chant and all the rest of the women who display such wonderful curiosity as to our kind of life are acting only like spies, and would give the world to know what the men really say to us.” “Englishwoman” really knows what Chant can only vainly desire to discover about the real world of men. Her greater proximity to men indicates her greater access to knowledge and prestige. The account of “Englishwoman” is intended to leave the lingering suspicion that mere power hunger lurks behind all of Chant’s claims of expertise in regard to the promenade. In turn, “Englishwoman” engages in a power struggle with Chant over the relative access of both women to social power, believed to reside largely in the knowledge of men and male society.

“A Londoner’s” account discloses the hidden fears raised by female philanthropists. “Englishwoman” denies that Chant knew male secrets, but many feared that Chant had gained this illicit knowledge from her reform work. Other women were anxious to separate themselves from female philanthropists, whom they alleged to be in thrall to the will to power. One correspondent declares, “I have found ‘women’ my cruelest, most memorable persecutors, and always under the guise of the desire to purify society and root out evil.”78 The writer stresses the unrelenting nature of female surveillance, with remorseless moralists undoing a husband’s generosity. The correspondent equates this disciplinary action with Chant’s attack on the Empire:

When sixteen I fell into the hands of a scoundrel who lured me into a bigamous marriage. Too late I discovered my betrayal. Eventually a professional man, of good social standing, knowing my history, made me his wife. I thought my wretched past was obliterated. . . . [A]ll went well with us until, in an evil hour, I encountered a woman, personally a stranger to me, but by whom, however, I was recognized. This highly respectable, conscientious lady, whom I had never injured in the least, held it her duty to “unmask” me, and to put a stop to the “contamination” of my presence in society.

The correspondent details the painful separation of husband and wife caused by “respectable” women. Like the writer’s nemesis, female philanthropists manipulate secret knowledge to their own advantage. Victorian surveillance worked on the principle that vision produced social knowledge; Chant dangerously works with what usually goes unseen. The results are “petticoat government” gone amok.

Both “A Londoner’s” interview and the autobiographical account above attack the work of women “spies.” The image of the female spy was a convenient counter to, and apparently a more accommodating image than, that of the female professional. In this rhetoric, the female spy is not in thrall to the higher authority of the state; rather, she stands as a cautionary case of unrestrained self-assertion. While the new professional is, as Burton Bledstein notes, believed to do more than “exclusively pursue a self interest,” the spy represents expertise tied to anarchic self-regard.79 In other words, the spy signifies an expertise sundered from any consideration of ethical means or the social good.

The spy also combines the pursuit of self-interest with an unattractive ignorance of her deepest desires. Constructing Chant as a spy spells out a public misconception of the philanthropist and reformer, especially the female social worker. Since it was commonly believed that women reformers could not approach their work without self-interest, it was not difficult to add to the charge and allege that their services were motivated by an unconscious will to power. The spy seemed to figure the real “desire” of the aspiring woman expert. It is a small leap from these suspicions to the direct allegation that female philanthropists were solely motivated by power hunger. Jerome K. Jerome’s editorial in To-Day takes special aim at the “evil thinking and evil-speaking meddlers” who have “grown like evil mushrooms in our midst”:

Lately a case was brought to my notice in which a poor and most respectable girl, utterly alone in London and working hard for her living, was deliberately hunted down from house to house by one of these wretched societies. That she could live by herself and be respectable they would not believe. They practically threatened every respectable landlady who gave her shelter, till at last they drove her to hide herself in a neighborhood where lodging-house keepers were less nervous of their reputations.80

These complaints about ruthless reformers reveal fear of the power that the reformer was believed to exert, an alarm over the “new breed of governing and guiding women” who wielded control over London and its environs.81 Indeed, Jerome charges that female “spies” now dominate the city, complaining that charity workers “for years past . . . have practically had the ruling of society.”

The charge of spying not only imputed venal motives to the reformers, but masked a deeper fear that they had already attained considerable power over men in late-Victorian London. It was more soothing for male elites to believe that Chant and the reformers were women on the prowl than to believe that they exerted power in the city, or that they provided real services for the city’s indigent women. “I have been to the Empire many times,” states a Telegraph correspondent, and the entertainment “does not shock the average Englishman half so much as the spectacle of this elderly woman dressed in ‘her prettiest frock’ vainly endeavoring to be ‘accosted.’”82 At a public meeting at the Prince of Wales Theater to protest the LCC’s decision to close the promenade, a music-hall manager charged that the witnesses against the Empire were indecent: “one of the women said she went to the Empire three times quietly dressed, and was not accosted [laughter]—and hence she went again, gaily dressed and was, as she alleged, then accosted. Probably the fact was so conspicuous that she was chaffed [Loud Laughter].”83 Such derisive laughter narrowed the distance between Chant and the women at the promenade; it reminded readers that both prostitutes and the middle-class expert strove to solicit the care and trust of the public. The jest assumes a structural resemblance between these various “professionals.”

The Sketch editorialist maintains the same ideological project, erasing the difference between Chant and the women in whom she took a professional interest. Women such as Chant, the Sketch claims, “who stand up in public and say what these women have been saying,” are already “indecent in the true sense of the word.”84 The Empire, the editorial writer wryly notes, must indeed be wicked if it holds men “who shall dare to accost gaily dressed Mrs. Chant out alone at night, even if her dress and her position shall seem to invite solicitation.” The Sketch recognizes little difference between Chant’s reform work and the prostitute’s vocation, as far as the police are concerned. As the editorialist points out, “if Chant behaved in Paris as she says she has behaved in London she might have risked being taken in charge by a sergent-de-ville.”

The Empire controversy circulated in correspondence columns, a forum that, as John Stokes observes, was widely considered as the “ideal structure for democratic debate.”85 Chant’s protest created instant authorities on popular amusement, the Empire, and prostitution even as these readers inveighed against supposed experts and authorities. Yet the controversy revealed a fear of democracy as well. The newspaper and periodical debate over the Empire suggests that the public looked primarily to “real” professionals—sometimes the police, sometimes the LCC inspectors, occasionally the Empire’s managers—to maintain order. And, while we traditionally think of experts as shutting off access to specialized knowledge, Chant’s maligned expertise was closely tied to democratic possibilities. Contrary to charges that she concealed dangerous secrets or dubious motives, Chant made “hidden” knowledge irrevocably public. Her efforts to publicize the “social evil” threatened elite control of these issues.

Considering the social effects of Chant’s protest, To-Day’s Jerome K. Jerome recalls the example of “Mr. Stead’s famous ‘Maiden Tribute’ articles”: these exposés of vice began as “perfectly legitimate pieces of work” but became dangerous when they fell into the wrong hands, that is, when they reached the general public.86 “The Truth that is excellent food for thoughtful men and women may be as harmful to the young and weak as brandy and beefsteaks would be to babes,” Jerome observes; when Stead’s accounts were “greedily devoured by shopboys and schoolgirls, they did incalculable mischief.” Likewise, Chant wrested the debate over the promenade from “thoughtful” men and women and placed the matter in untrained hands. “I do not care to see the details of the social evil,” Jerome complains, “presented in an attractive guise in the pages of a newspaper that can be bought for a penny.” Jerome reminds us of the dangers experts could present to the dominant order when they attracted publicity, acting as conduits for the spread of unauthorized knowledge. Jerome is alarmed by the possibility of achieved democracy, with an entire populace in the know. Through the engines of the press, Chant threatened to provide the public with access to “details” about a “social evil” that they could not be trusted to process.

The responses to Chant reveal an apprehension over the very real power Chant wielded as reformer, a power not limited to visual power or the panoptical apparatus of the promenade. Chant was an intruder in male spaces who was believed to know too much; her field of expertise was too dangerous to permit her to be generally recognized by a male elite as an expert. Her maintained ties to dissent presented another obstacle to her recognition within the managerial class she aspired to join, for the members of this class were increasingly trained to respect secular protocols of knowledge. In contrast, Chant countered the scientific fatalism that dominated the opinion of medical professionals on prostitution, which claimed that it might be regulated, but not eradicated. She assigned a determinate point of origin, and blame, to men for the perpetuation of the “social evil.” Her modes of social investigation—assuming a disguise, personal contact with prostitutes—seemed mistaken or counterproductive to a segment of the managerial class, and unseemly assertions of feminine power to others.87

Still, we might be able to reconstruct with some fairness what Chant hoped to achieve with her investigation of the Empire, even if her proposed reforms were never actualized. In “State and Society,” Stuart Hall and Bill Schwarz elaborate on the increasing tendency of state policy to turn to the regulation of culture and amusement in the years between 1880 and 1920, and delineate mass culture and civility as the conceptual products of statist power. As Chris Waters details, the late Victorians witnessed a fateful marriage between mass culture and state organization; theirs was “an era in which the state and the municipality [intervened] more directly in the field of popular culture than had hitherto been the case.”88 Chant took the London County Council’s initial decision to close the promenade not as a personal victory but as a momentous public event, similar to “the signing of the Magna Charta [sic] for public amusement.”89 Her dramatic appeals before the still novel, and often feared, LCC suggest her understanding of the Empire battle as her contribution to a new interventionist state and the “modern” administration of culture in the metropolis.

Chant suggested that the demeanor of Empire manager George Edwardes when she cross-examined him during the LCC’s hearings demonstrated the progressive tenor of the times. “In former days,” she reminded the press, “if a woman had got up to cross-examine a man upon such matters ribald laughter and indecent suggestion would have been hurled at her.”90 Edwardes’s behavior suggested that millennial change—or at least major civic reform—was close at hand. Against these apocalyptic expectations, the total abolition of the trade in women seemed possible, even foretold by historical precedent. In Chant’s words, this abolition would not be “more Quixotic than the actions of those who agitated for the abolition of the slave trade.” It should be remembered that Chant was a Congregationalist and a pioneer advocate of a woman’s right to speak from the pulpit.91 Her claims here again reveal her occasional discomfort with an increasingly secular discourse of management. They also suggest her personal distance from an administrative or disciplinary apparatus geared toward the management of souls rather than their cure. Her millennial fervor proclaims her confidence that reform, management, and dissent were closely allied. While the new managerial class was often trained within dissenting traditions, and circulated their message through the printed and pedagogic organs of dissent, many new reforms were separating the exercise of managerial power from Christian practice.92

A large component of Chant’s protest was the achievement of a secular brand of recognition, the enhancement of her cultural capital within a broader social network. Cultural capital, as elaborated in Pierre Bourdieu’s careful anatomy, exists in a variety of forms. In Beverly Skeggs’s useful gloss, such capital exists in “the objectified state, in the form of cultural goods; and in the institutionalized state, resulting in such things as educational qualifications.”93 Yet, as Skeggs adds, all forms of capital—economic, social, cultural, and symbolic—require public recognition if they are to profit their owner. In her words, “Legitimation is the key mechanism in the conversion to power. Cultural capital has to be legitimated before it can have symbolic power.” A fierce, protective discourse of partisanship, exemplified in one mode by the true-born Englishman, and in another by the aesthete, denied Chant’s claims to legitimacy. Partisan discourse became hegemonic, a species of common sense that now incorporates a strain of hedonistic consumerism.

This is not to say that Chant’s desire to attain symbolic capital, inherent in her desire to be recognized as an expert, situates her within the more culpable middle-class project of attaining full hegemony over subaltern groups. Chant refused to conceptualize her expertise according to a traditional logic, in which experts speak from above to the lowly crowd below. She spoke for the popular in a relatively tolerant and generous manner. Chant believed in the role of mass culture within a renovated civic life. This aspect of her public pronouncements was often overlooked, and sometimes derided, by the media. However, in a lengthy interview conducted by the largely critical Pall Mall Gazette, Chant has much to say about the functionality of mass culture for the reformed society. “I stand, perhaps, rather apart in this from my colleagues, for I am passionately fond of dancing, and exceptionally fond of acting, and I look upon dramatic representation both as an amusement and as an education. I regard it as being the great power of the future. It is because I want that power on our side, and not against us, that I am so anxious to safeguard the stage against impurity.”94 Chant speaks of the popular and also seeks to represent it. Like her imagined peers on the London County Council, she hoped to foster “a more interventionist strategy with regards to the nation’s culture life.”95 This optimistic progressivism was gainsaid by Chant’s failure to close the Empire promenade once conservatives were elected to the LCC; nevertheless, her concern to elaborate on the service element within professional culture complicates a simple explanation or unmasking of her activities.

In spite of Chant’s presumptuous attitudes toward working-class men and women, her attempt to gain a measure of “feminine” control over homosocial spaces clearly deserved a more complex response than the monochrome derision and opprobrium it in fact received. Her bid to shut down the public display of vice, which entailed augmenting the power of a centralized state to intervene in cultural life, was a provocative effort to refigure London’s “geography of sex.” Chant’s fortunes in the media, at the hands of the circulating press, indicate that she failed in the articulation of her reform to the forces of consumer and professional culture with which she identified. It appears that a largely vocal male consensus in the press, rather than Chant’s “regressive” politics, was the primary reason that her attempts to articulate her reform to these forces failed.96

Professional culture, as well as Chant, lost in the public debate. As Bruce Robbins reminds us, “professionalism need not be a zero-sum game in which professional knowledge establishes its authority only by eliminating the knowledge and authority of someone else.”97 The victory of Chant’s opponents ensured that a simplistic notion of professionals became consensual, resulting in an impoverishment of our public culture, then and now, since professionals remain largely misunderstood and roundly disparaged. For many male observers and most music hall connoisseurs, it seemed clear that recognition for Chant required a disavowal of their own authority: as men, fans, citizens, and experts. It was a sacrifice most men were unwilling to make. Chant’s opponents treated the dispute over the Empire as a kind of zero-sum contest for authority and expertise.

It is certainly time to extricate Chant from these simplified images. Reading her protest as another species of Victorian discipline overlooks a crucial point: that an apparently normative, moralist appeal to public reform failed to take with the general public, especially with a vocal segment of the Victorian managerial class. Chant’s attempts to speak on the public’s behalf worked within existing systems of social hierarchy. The result was a compromised endeavor that will not please those social critics who prefer that critique occur at a safe, antiseptic remove from power.98 To simplify Chant’s motivations in the Empire affair compounds the injuries done to her a century ago, when she publicized her claims to be a professional.99

Why is the “Prude on the Prowl” like a poor art critic?

Because she objects to the pictures that are well-limbed.

The jibe is from the Music Hall and Theatre Review;100 the punning conflation of “limbed” with “limned” looks at Lady Somerset’s public efforts to censor the Living Pictures (live models re-creating high art tableaux) at the Palace Theatre of Varieties, just as Laura Chant worked to strip the Empire of its license. The joke tells us a great deal as to how the temperance reformer was figured in media controversy. The urban professional was figured a puritan; by definition, puritans are unable to think in sophisticated terms about art, or appreciate art for its own sake, outside reference to a rigid, strictly defined moral code. Chant’s dissent against class and gender privilege was framed as a tasteless endeavor, a violation of the aesthetic decorum respected by the polite middle class and the aristocracy. The opposition was marked by an entente between two class factions that otherwise existed in tense relation during the period, but who fell in together as natural allies on this occasion, sharing a common desire to protect masculine prerogative. The alliance between upper-middle-class and aristocratic patrons of music hall was based on the shared predilection to preserve the privileges of flaneur-style mobility for male citizenry of the metropolis.

In contrast, Chant belonged to a group of nascent state intellectuals and progressives who were reconfiguring the public sphere, hoping for a more efficient administration of metropolitan life, guided and transformed by the work of trained and certified experts. Like Chant, these other experts had proved themselves in the maelstrom of the city; they knew the city’s ills and ailments, and worked at projects for the large-scale renovation and renewal of urban life. Chant believed that music hall at its best produced “rational amusement” for the improvement or solace of the masses. Yet this tenet of faith was maintained by Chant with a generosity not shared by a large segment of public opinion within the managerial sector.101 Ironically, in comparison with many of this class, Chant, the so-called sanctimonious puritan, evinced considerable faith in the possibilities of mass culture to improve the public. She suggested that the theatrical arts and music hall had the capacity to uplift, as much as the museum or municipal art gallery, the primary choices of the managerial class for productive technologies of cultural enhancement.

Chant’s desire to be recognized as an expert on mass culture may appear to be so much middle-class aggrandizement, or to correspond with an elitist narrative of expertise. Yet she entertained a fluid conception of the public she represented, and framed her postulates about popular taste in an attractively tentative fashion. Unlike many of her colleagues in the temperance and suffrage movements, Chant often took pains to emphasize in her public pronouncements the relative autonomy of art and amusement from a heavy-handed moralism. The woman designated by the print media as the “Puritan on the Prowl” spoke in favor of art, but often divorced the experience of art and pleasure from the exclusive idiom of taste that governed the discourse of the professional spokespersons for belles lettres. Chant issued provocative statements such as this during the height of the Empire controversy, according to the press: “No doubt some of the entertainments thus provided [by the halls] might be vulgar, but she had no more fit to quarrel with a vulgar entertainment than with a vulgar bonnet.”102 Possibly the most controversial aspect of Chant’s protest against Victorian gentlemen was her ability to occupy a class-specific taste idiom, while at the same time refusing to police aesthetic hierarchy. The reformer did not appear to be honor bound to reform or combat public “vulgarity.”

In marked contrast, aesthetic professionals, such as Arthur Symons, routinely relied on a construction of the fully autonomous, well-regulated, and properly aesthetic space in order to counter Chant’s intervention. The Empire as an aesthetic artifact had more authority than meddling reformers, and was above the social fray. It also existed outside a potential feminist critique. Chant endeavored to avoid associating training with exclusive power, the representation of popular taste with a compulsory tutelage of the public. In contrast, aesthete defenders of the Empire often worked unabashedly to authorize their amoral views of prostitution as common sense and just public policy. For example, Arthur Symons’s correspondence to the Pall Mall Gazette finds the poet assuming the role of cultural expert to defeat Chant’s own claims to know the popular. He takes especial aim at the reformer’s professed knowledge of aesthetic values. In Symons’s estimation, Chant made the mistake of a novice viewer before a complex, nuanced experience; she imposed a moral prejudice on a space and practice that required proper perspective, attainable through careful training and self-imposed discipline. Despite the modest disclaimer that the poet/critic provides, that he cannot pretend to know “all about the music hall of every continent,” Symons claims to have well researched the issue at hand. “I have made special study of music-hall entertainment, and visited music-hall in Paris and throughout France, in Belgium, in Germany, in Italy and in Spain, and I can only say that, in my opinion, the Empire is, as a place of entertainment, the most genuinely artistic and the most absolutely unobjectionable that I know in any country.”103 This confident, expansive declaration positions the cosmopolitan aesthete against the more provincial, and therefore less discerning, views of the visiting prude. The aesthete speaks in the capacity of the self-appointed, self-authorized music-hall inspector whose work entitles him to speak for the form from a universal viewpoint. Symons, the music-hall professional, demonstrates his authority through ready recourse to his vast knowledge of the subject matter of music hall. Professional rhetoric is linked with a position on the relative autonomy of the aesthetic. A well-regulated space is a “genuinely artistic” one, and therefore beyond the criticism of untrained interlopers.

Symons’s letter to the Pall Mall Gazette moves the Empire debate further from the “presence or absence of ‘loose women’” in the promenade toward the more specialized topic of aesthetics, which the poet can address with a confident, and convincing, authority. Cultivating the Empire as an aesthetic concern means breaching with a conservative moralism, often associated with conservative views in cultural matters. Aestheticism is made to serve the ends of liberalism and an accordingly “progressive” position on the issue of prostitution. “By closing the promenade you take from the Empire, which is a music hall, its privileges as a music hall and reduce it to the level of constraint and discomfort of an ordinary theatre. . . . Now one of the chief charms of the music hall would be gone at once; for the great secret of music hall’s success is that . . . you are not obliged to sit solemnly through a whole evening’s performance but can take your pick of the programme.”104 The rhetoric of insider knowledge convinces in part because it honors a professional decorum; it imagines the music hall according to special, or specialized, definitions. Symons writes in the special language of the trained expert, who, as Burton Bledstein observes, marshaled “esoteric knowledge” and “a special understanding of a segment of the universe.”105 Chant, by comparison, appears the mere amateur, motivated by moral considerations that set her at odds with a space organized according to esoteric, complex, aesthetic standards. “Prudes,” the connoisseur intimates, are culpable for their neglect of the aesthetic properties of music-hall space, and for ignoring the rules that trained observers realize are actualized in the structure of the entertainment. The controversy is evacuated of its potential social significance, and the orderly promenade comes to “naturally” represent essential qualities of decorum.

Paradoxically, the meddling prude threatens to rid “music hall” of what in principle it could never lose: its essence. The promenade is imagined to be the supplement necessary to secure the aesthetic character of the Empire. As Symons warns the Gazette’s readers, the effect of closing “the space [of the promenade] would be, not to place the Empire on the footing of the Tivoli and the Palace [music halls], but to deprive it of every outward characteristic which distinguishes a music hall from an ordinary theatre while giving it no advantage as a theatre.” Chant and kindred reformers are guilty of reading the promenade by solely moral criteria, rather than properly formalist ones.

Symons’s correspondence on the Empire controversy strives to save the matter from what he considered a significant misreading of music hall by the “prudes,” a reading perpetuated in the debate over its legality. For the aesthete, music hall must be appraised like any art form, by a consideration of its properties, form, and function; the entertainment must be read according to the “aesthetic disposition” described by Pierre Bourdieu.106 The amateur overlooks the structural function of the promenade that distinguishes Symons’s idealized, integral “music hall.” Naturally, these errors of omission are to be expected of the novice; the proper aesthetic disposition and the correct reading of the space remain the exclusive property of specialists—those who, in Symons’s own words, “talk about music hall for a living.”

Arthur Symons’s correspondence on the Empire revises some aesthetic doctrines from within the discourse. He displays an unconventional notion of the high/low cultural divide in the casual comparison between theatrical entertainment and music-hall amusement drawn in his correspondence against Chant published in the Gazette. The poet parts ways with authorities such as Henry Arthur Jones and William Archer in finding significance and a degree of pleasure in the distractions that accompany the music-hall experience in contrast with the more concentrated, and, by implication, more cognitively challenging, pleasures of the drama. Yet if Symons appears to trouble one tenet of good taste, he maintains a key taste axiom intact. His definition of music hall in structuralist terms serves to mark off territory from untrained observers, from those believed incapable of attaining the distance from the entertainment that might allow them to formulate a precise, and therefore authoritative, conceptualization of the form. Nothing less, it seems, can ground an adequate reading of the Empire. Symons’s quarrel with the work of Chant and her “prudes” is in contrast with the later entente he achieves with a woman he recognizes as a peer and fellow literary professional, Olive Schreiner. The critic demonstrates a willingness to revise his taste protocols, even critique his expert stance, in “At the Alhambra,” an essay he publishes two years later. There he will cede the high ground of a “trained,” formalist perception to the opinions voiced by a woman “novice.” The dialogue between them encourages Symons to abrogate his achieved authority. In the controversy raised by Chant over the legitimacy of the Empire as a “true” music hall, Symons assumes a more conventional stance: that of the paternalist, juridical intellectual. In his public pronouncements on the fray, he works to correct the untrained misconceptions brought by amateurs like Chant to a special field too complex, it is insinuated, to be mapped by mere novices.

While marshaling their forces against Chant’s perceived inability to distinguish between artistic spaces and dangerous urban zones, literary and theatrical professionals alike endeavored to aestheticize the Empire. In their accounts, the promenade became associated with order, autonomy, and a freedom of movement that, in Symons’s case, signified the imaginative freedom that was believed to be a hallmark of aesthetic experience. Others suggested that the Empire offered the disinterested consumer a similarly distanced apprehension of the “beautiful,” achieved through a vision of available, but removed, femininity. These constructions of the Empire had at least two discernible effects: first, they cordoned off the Empire from “interested” social groups such as philanthropists, setting the Empire under the control of more capable—that is, aesthetically discerning—professionals. Second, they had the subsidiary effect of demoting Chant’s social critique to incurable “bad taste.”

It was suggested in the pages of the Sketch that the final word on the entire debate would belong to artists, to those who crafted visual responses to Chant’s public protest in the press. Sketch artists, as we have seen, found Chant’s project an appealing subject, a veritable incitement to representation. The Sketch, for instance, coupled its coverage of the civic controversy with illustrations taken from Raven Hill’s sketchbook The Promenaders, which provided twenty-two full-page drawings depicting the dispute over the Empire and the promenade.107 The Sketch describes three Hill sketches satirizing Chant and praises his depiction of the Empire, which it printed on the facing page. The editorialist in fact happily follows Hill’s lead in glamorizing the promenade according to the conventions set by sophisticated continental painters of consumption such as Degas and Manet. Hill’s sketch frames the controversial promenade as a controlled, impressionist landscape, rather than the spectacle of vice (figure 4). The Sketch editorialist, perhaps inspired by Hill’s example, goes the artist one further, admitting that the Empire promenade is a meeting place for rough trade, for promiscuous assignations between the demimonde and male patrons, yet insisting that it remains, in his words, fully “tasteful.”

Nearly forty years later, the distinguished publisher Grant Richards would confirm in his memoir the Sketch’s early prediction that the Empire dispute would be “won” by men of taste, not meddling reformers. Richards recounts the controversy from a fully aesthetic, that is, a moral and asocial, perspective. He relies on metaphors from the exclusive world of painting and portraiture, the locutions of high art practice, to frame the routine experience of closing time at the Empire. Long after the event he frames the Empire as high artistic endeavor, part of a complexly imagined and elegantly impressionist vision: “The scenes at the moment of closing-time outside these various places of resort would astonish people to-day, but they had the quality of being picturesque. Manet might have painted one or other of the little groups—Manet or Toulouse-Lautrec or Felicien Rops.”108 Richards goes on to extol the Empire—safely situated as high art—with “its dark Whistlerian wall decoration” and with “women [if] not all beautiful” at least “fitted more or less beautifully into their background.”109 In his memoir, the Empire controversy loses its social referents and becomes reterritorialized within the aesthetic.

Figure 4. Music hall as high art. “‘The Empire’—The Decline and Fall.” From Sketch, October 31, 1894, 9. (By permission of the British Library)

Richards’s retrospective view of the Empire controversy takes its cue from the caricature of Chant that proliferated in the period; he recalls how Chant “and her devoted busy-bodies” had “the worldly press against them and the graphic artists who dealt in amusement.” The account concludes with a nostalgic lament for the loss of “colourful” spaces in the city where men of privilege could meet in open, yet clandestine, fashion with “decorative” women. In his reckoning, the actual closing of the Empire promenade after World War I only further sublimated an already sublimely elegant reality, transforming it into a safe and decorous ideal. Sexual impulse sublimated into an airy phantasm: this was a tried and tested modality of the aesthetic imagination. As a result of the reforming impulse, fortunately vanquished in Chant, but renewed by martial fervor, the encounters permitted in well-regulated spaces such as the Empire were “driven to frequent the museum of the artists’ fancy.” Richards’s account inscribes Chant and the Empire into a series of images and representations existing at a considerable remove from material facts.