2.

Buried Alive

In the past, some Chinese constructed shengkuang or ‘living tombs’ for themselves or their relatives while they were still alive. For Zheng, life in prison is like being buried alive, in a coffin pit that he has dug for himself. In this bleak poem, which Zheng wrote at the age of around sixty, he reflects on his long years in jail and the mental scars caused by the severing of his relationships with family and friends. The mountain rock stands for the callousness of China’s political regime and of prison life. Kiyama Hideo explains that mountain rocks represent lack of feeling, in contrast to Zheng’s excess of feeling, and ties the notion that mountains have no sense of time to the Zen saying, ‘In the mountains there are no calendars.’

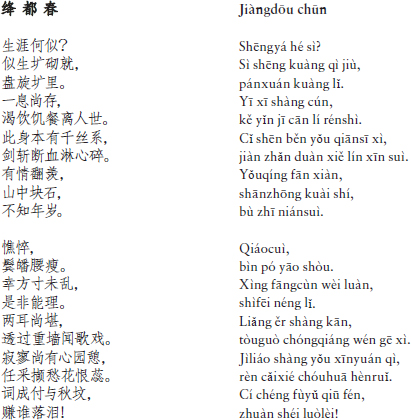

To the tune of ‘Spring in the Crimson City’

My career?

It’s like the coffin pit you dig before your death,

to potter in while still alive.

As long as I have breath,

I’ll doubtless quench my thirst and still my hunger behind bars 5

– but how to live, when kept apart from family and friends?

These limbs display a thousand rends

cut by the sword that slashes through my ties.

My feelings turn to envy

of the mountain rock that never counts the years. 10

Pale and haggard,

emaciated and white-haired,

luckily I can still think straight,

can still tell wrong from right.

Both ears still work, 15

and through the prison wall I hear an opera.

Though lonely, I stroll within the garden of my mind,

plucking flowers of sorrow and regret.

This poem is written for an autumn grave,

but who will do the weeping? 20

_______________

Line 16: Chinese folk opera, staged in villages.

Line 19–20: These last two lines are a variation on the last two lines of Poem 40, ‘Self-Congratulations on My Sixtieth Birthday’.