38.

Wartime Sojourn in Anhui

In 1996, Zheng commented on the background to this poem:

This poem records my life in Southern Anhui, escaping from the war. When the war broke out and the Japanese bombed Nanjing, the Guomindang decided to move its capital [first to Wuhan and then to Chongqing to the west] and to ‘evacuate the prisons’. Starting in around August, the Central Military Prison began freeing inmates. The Guomindang explained that ‘evacuating the prisons’ was common practice in modern states in extraordinary times. Most people said it was one of the conditions put forward by the Communist Party during the second period of cooperation with the Guomindang,1 I don’t know if that’s true. Whatever the case, the Central Military Prison released not just political prisoners but common criminals and military prisoners, and eventually even some long-term non-political prisoners were released and sent to the [Guomindang] rear.

At the time, I was in a single cell with He Zishen,2 who only had a few months left to serve. On 20 August, he underwent various prison formalities and was released the next day. He found out where my wife was living, and she took him to Huqiao Prison where Chen Duxiu and other comrades were being kept. They had not yet been released. Chen Duxiu had already arranged for He Zishen and my wife to go not to Shanghai but to Jixi in Anhui, where Wang Mengzou’s3 great-nephew lived, to recover. I was freed on 29 August. Chen Duxiu had already been freed on 23 August, and was staying with Chen Zhongfan. We went to see him, and slept the night on his floor. The next morning we left Nanjing for Wuhu, and spent the night in Wang Mengzou’s Science Book Club. The next day, we took a long-distance bus to Jixi. I was not happy to go to Jixi to recover, I wanted to go back to Shanghai and resume long-term work there. But then I heard that Shanghai’s South Railway Station had been bombed and the trains had stopped running, so I gave up the Shanghai idea for the time being.

Who would have thought that I would stay in Jixi for almost three years? At first we stayed with Wang Mengzou’s family, but later we rented a house from Wang Mengzou’s nephew, said to be the best private house in town. Japanese planes bombed the town, and the rich fled to the countryside. We followed the Wang family to a nearby village and stayed there until after the lunar New Year. He Zishen went back to Hunan.

Just before the Festival of Pure Brightness,4 it was rumoured that the Japanese were about to advance from Xuancheng to Huizhou, so the rich families took to the mountains. Wang Naigang set up a primary school in the village and let my wife teach at it, so that the children would not miss out on their education and we could make a meagre living. To pay the bills, I intended to do some translating, but my wife fell pregnant and I had to take over from her. I taught by day and translated by night. During the summer, I opened a cramming school. After the summer holidays, things settled down. The rich people moved back into the town, and so did we, in September. On 5 November, our son Frei was born.

In 1939, in a place southwest of Jixi, a rural school needed a maths teacher, so I had to put aside my translation work and start teaching. I later learned that the headmaster, Zhu Dading, a returned student from Japan, was a member of the Communist Party. Some of the teaching staff were members of the Guomindang and even of the CC Clique. They turned against the headmaster and encouraged the students to boycott classes. The school lacked funding, so I taught for one or two months without pay. According to government provisions, every teacher had to give a written guarantee that he or she would ‘not violate the Three People’s Principles’, so I decided to quit the job.

After resigning, I concentrated on my translation work. I translated Trotsky’s masterpiece The Revolution Betrayed, Victor Serge’s L’an 1 de la révolution russe (‘Year One of the Russian Revolution’), Gide’s Voyage au Congo (‘Voyage to the Congo’), Hedin’s Durch Asiens Wüsten (‘Through Asia’s Deserts’), and other books. I did some of the translating in the town and some in a village, where I again went to escape the bombing. When I returned to the town from the village, I lived for two-and-a-half years rent-free in the home of Chen Xiaoqing, a partner in [Wang Mengzou’s] Oriental Book Company. I only learned afterwards that Chen Xiaoqing was an old revolutionary who had taken part in the Revolution of 1911, helped sponsor the May Fourth Movement, and joined the Communist organisation, although he never told anyone, not even his two sons. When our Trotskyist Comrade Chen Qichang was captured by the Japanese, Chen Xiaoqing rushed to tell me, and warned me that spies might be living nearby.5

In late March 1940, [the Trotskyists in] Shanghai needed my presence and sent us the money for tickets. I, my wife, and our newborn child Frei crossed rivers and mountains, by way of Tunxi, Lanxi, Jinhua, Yiwu, Xikou, and Ningbo, and eventually caught the boat back to the lonely island of Shanghai.6

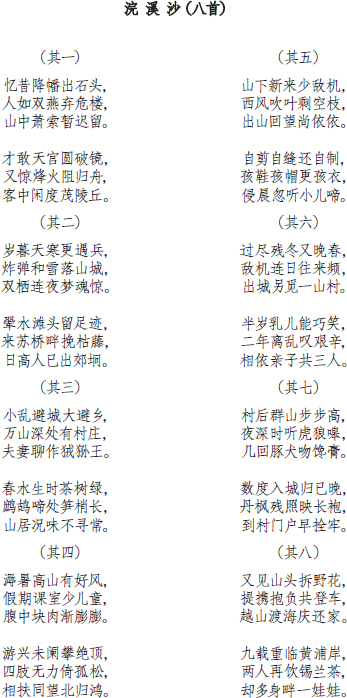

To the tune of ‘Sand of the Silk-Washing Brook’

(One)

Above Stone City fly surrender flags.

Like swallows flying out from falling towers,

we take in desperation to the hills. 3

Heaven put us back as one, but flames of war

stand in the way of our return by boat.

We while away our autumn days high in the Maoling hills. 6

(Two)

The year is nearly up and cold sets in, while fresh troops join the fight.

Bombs and snow fall side by side upon the mountain town,

and after dark we cling together in sheer mortal fright. 9

We skim the stream and stamp the bank,

and see the Suzhou bridges, clogged with reeds.

At dawn we reach the outskirts of the town. 12

(Three)

Small disasters drive us from the town,

while big disasters drive us from the fields.

The two of us build shelters in the hills and live like monkeys there. 15

Spring rains turn the tea bush green.

In the bamboo groves the francolins call out –

the mountains cast their spell. 18

(Four)

On hot and humid days, the mountain breezes blow.

Few students attend classes out of term,

and my belly swells. 21

Intent on climbing right up to the top,

we pause to lean on lone pines.

Clutching each other tight, we watch the geese’s northward flight. 24

(Five)

Below us, fewer hostile planes wheel through the sky.

A west wind strips the branches of their leaves.

Reluctantly, we leave the hills. 27

We cut cloth, sew, and make our things ourselves –

Frei’s coats, his shoes, his wraps and hat.

Before dawn breaks, we wake up to his crying in his cot. 30

(Six)

The winter has been harsh, and spring is late.

Enemy planes turn up without respite,

driving us back into the countryside. 33

Our suckling child at six months has a winning smile.

It’s two years since we fled the chaos for this vale of tears:

we’re now three people – father, mother, and a baby child. 36

(Seven)

Behind the village tiered hills climb towards the sky.

At night wolves howl and tigers roar,

stealing and killing local dogs and pigs. 39

Sometimes we arrive home late,

when the flaming maple’s flame is all but spent

and the crosspiece fastened to the village gate. 42

(Eight)

In the hills we pluck wild flowers.

Loyal to our old ideals, we ride the bus

back across hills, and sail the sea, and celebrate arriving home. 45

Out on the Huangpu River for the first time in nine years,

the two of us drink Ceylon tea –

now no longer two but three. 48

Huán xī shā (bā shǒu) |

|

(Qí yī) |

(Qí wŭ) |

Yìxī jiàngfān chū shítou, rén rú shuāngyàn qì wēilóu, shānzhōng xiāosuǒ zàn chí liú. |

Shānxià xīnlái shǎo díjī, xīfēng chuīyè shèng kōngzhī, chūshān huíwàng shàng yīyī. |

Cái gǎn tiāngōng yuán pòjìng, yòu jīng fēnghuǒ zŭ guīzhōu, kè zhōng xián dù Màolíng qiū. |

Zìjiǎn zìfèng hái zìzhì, háixié háimào gèng háiyī, qīnchén hūtīng xiǎo’ér tí. |

(Qí èr) |

(Qí liù) |

Suìmù tiānhán gèng yù bīng, zhàdàn héxuě luò shānchéng, shuāngqī liányè mènghún jīng. |

Guòjĭn cándōng yòu wǎnchūn, díjī liánrì wǎnglái pín, chūchéng lìngmì yī shāncūn. |

Huīshuĭ tāntóu liú zújì, Láisū qiáopàn wǎn kūténg, rì gāo rén yĭ chū jiāojiōng. |

Bànsuì rŭ’ér néng qiǎoxiào, èr nián líluàn tàn jiānxīn, xiāngyī qīnzĭ gòng sān rén. |

(Qí sān) |

(Qí qī) |

Xiǎoluàn bìchéng dà bìxiāng, wànshān shēnchù yǒu cūnzhuāng, fūqī liáozuò róngsūn wáng. |

Cūnhòu qúnshān bùbù gāo, yèshēn shítīng hŭláng háo, jĭhuí túnquǎn wěn chángāo. |

Chūnshuĭ shēngshí cháshù lǜ, zhègū tíchù sŭnshāo zhǎng, shānjū kuàngwèi bù xúncháng. |

Shùdù rùchéng guī yĭwǎn, dānfēng cánzhào yìng chángpáo dàocūn ménhù zǎo shuānláo. |

(Qí sì) |

(Qí bā) |

Rùshŭ gāoshān yǒu hǎofēng, jiàqī kèshì shào értóng, fùzhōng kuàiròu jiàn péngpéng. |

Yòujiàn shāntóu chāi yěhuā, tíxié bàofù gòng dēngchē, yuèshān dùhǎi qìng huánjiā. |

Yóuxīng wèilán pān juédĭng, sìzhī wúlì yĭ gūsōng, xiāngfú tóngwàng běiguī hóng. |

Jiŭzǎi chónglín huángpŭ àn, liǎngrén zàiyĭn xīlán chá, quèduō shēnpàn yī wáwá. |

_______________

‘To the tune of’: A song by the statesman and poet Yan Shu.

Line 1: This line is modelled on a line in a well-known poem by Liu Yixi. Nanjing is also known as the City of Stone, especially in literary works.

Line 46: Zheng and Liu returned to Shanghai (and its Huangpu River) in 1940, nine years after Zheng’s imprisonment in 1931.