Histories of Male Hustlers

In his 676-page History of Prostitution, published by the Eugenics Publishing Company in 1939, William Sanger (a medical doctor from New York) discusses male prostttution in only one short paragraph. Sanger writes:

This hasty classification of the Roman prostitutes would be incomplete without some notice, however brief, of male prostitutes. Fortunately, the progress of good morals has divested this repulsive theme of its importance; the object of this work can be obtained without entering into details on a branch of the subject which in this country is not likely to require fresh legislative notice. But the reader would form an imperfect idea of the state of morals at Rome were he left in ignorance of the fact that the number of male prostitutes was probably fully as large as that of females. (p. 70)

This near negation of the mere existence of the male sex worker is a stream that runs through many writings on and histories of prostitution that appeared during the early 20th century in the United States.1 In Sanger’s work, male prostitution, understood to be a “repulsive” act that is fundamentally linked to the Greeks and Romans, is said to have been eradicated by society’s “good” morals.

Occasionally, an author such as George Scott (1936), in his History of Prostitution from Antiquity to the Present Day, discusses male prostitution at some level of historical depth (although even this “depth” is still only 11 pages of a 231-page book).2 Scott’s history, published two years before Sanger’s, chronicles the male prostitute’s role in society via biblical writings and thus is also highly influenced by a moral hierarchy, in that, for Scott, the bulk of male prostitution is fundamentally linked to homosexuality and savagery. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Scott repeatedly attempts to qualify and nuance his discussion of male prostitution in relation to male homosexuality, breaking down the demand for male prostitutes into subcategories.3 In much the same way Sanger discusses male prostitution as something that must be named but is relatively unimportant, Scott brings in a discussion of the gigolo, a male prostitute who is not a homosexual and whose sex acts, therefore, hold “no criminality … and no perverse practices” (p. 186). Scott’s discussion of the gigolo, who has sex exclusively with “sex-starved women” (p. 187) for pay, is simply a note in passing; he is a prostitute, yes, but only by definition, and he is certainly not characterized by “perversion,” as is the homosexual male prostitute.

Two things become strikingly apparent from these early histories of prostitution: (1) that male sex workers have been severely under-discussed in histories of prostitution; and (2) when male sex workers are written about historically, the “problem” of male sex work is fundamentally linked to the “problem” of homosexuality. These two elements are crucial to understanding the dominant representations of the male sex worker in American cinema before the emergence of the New Queer Cinema movement in the early 1990s.

Male Hustlers in Cinema

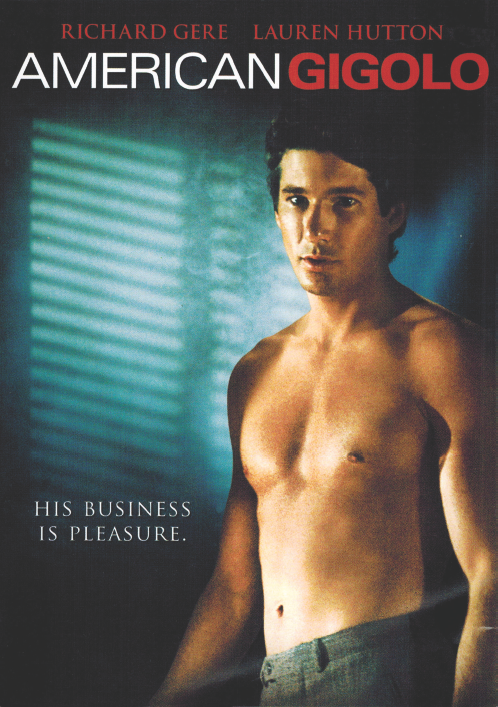

While films such as Midnight Cowboy (Schlesinger, 1969) and American Gigolo (Schrader, 1980) presented some of the first widely accessible images of the male prostitute in American cinema,4 the characters of these films fall exclusively within the realm of the gigolo. These gigolos openly acknowledge and embrace the idea that homosexual male prostitution is abject in a fundamentally different way than heterosexual male prostitution, capitulating to homosexual sex only when their circumstances become dire.

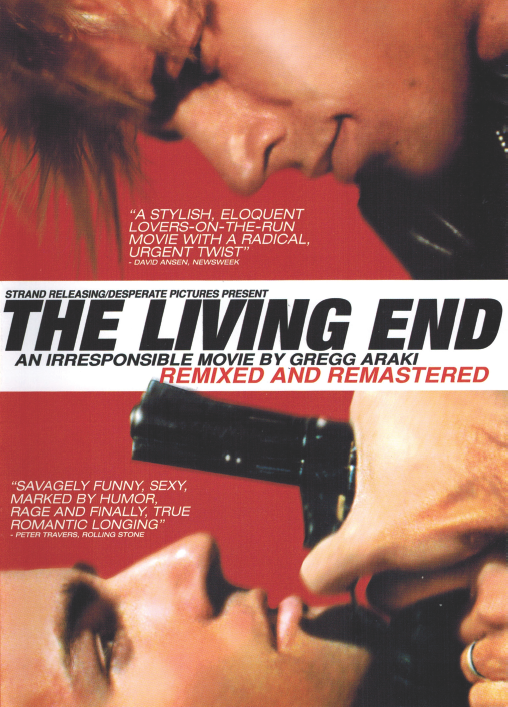

New Queer Cinema, informed by the AIDS crisis and the U.S. government’s poor response to it in the late 1980s, provided films that presented new ways of seeing gay characters—including the male sex worker. Two films in particular, The Living End (Araki, 1992) and My Own Private Idaho (Van Sant 1991), both deemed a part of the New Queer Cinema movement by B. Ruby Rich (2004) in her canonical essay, “New Queer Cinema,” participate in a significant discourse that has worked to question historical understandings of the male sex worker in a way that marks a drastic shift from the films of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

American Gigolo presented one of the first widely accessible images in American cinema of a male prostitute who serves women. The main character nearly turns to homosexual sex, but only when his circumstances become dire. Reproduced with permission from Paramount Pictures.

The Living End, which follows the road-trip adventure of a spontaneously violent, macho, and newly diagnosed HIV-positive hustler and his lover, is described as a film of “almost unbearable intimacy.” Reproduced with permission from Strand Releasing.

To a certain extent, the male hustler was a character type in cinema decades before Midnight Cowboy, but not in the way the term has come to be defined. “Hustler” currently applies most often to men who “[engage] in homosexual behavior” for pay (Steward, 1991, p. xi). However, if we understand the term “hustler” as someone who hustles and is “looking for something, and who sooner or later finds himself pretending to be something he isn’t, or thinks he isn’t, or wishes he were, or doesn’t realize he wishes he were” (Lang, 2002, p. 249), we raise the possibility that a hustler may be hustling for any number of things—clothes, a place to stay, or money, for example—and may exchange other services, like time or company, without explicitly selling sex. In this way, characters who may, for all intents and purposes, be gigolos could be passed off in code-era Hollywood as “kept men.” The hustler as a kept man applies to any number of characters from 1940s-1950s Hollywood, such as Joe Gillis (played by William Holden) in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) or Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) in Vincente Minnelli’s An American in Paris (1951).

Sunset Boulevard provides a particularly interesting example because it toys rather explicitly with the content restrictions of the Motion Picture Production Code. On the surface, Sunset Boulevard figures Joe as a kept man who—in Ed Sikov’s (1998) words—“survives by smoothly humoring his patron” (p. 297) by writing for her, dancing with her, and living in her home. Even though the film never shows a sex act between its characters, the implicit notion that Joe also has sex with his benefactress is made relatively clear, as various commentators have noted. Sikov, for example, explains that Joe survives “first by writing a part for [Norma] in a movie that will never be made, and then by making love to her” (p. 297). Joe explains his relationship with Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) to his young love interest, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), by saying, “It’s lonely here, so she got herself a companion. A very simple set-up: an older woman who is well to do, a younger man who is not doing too well. Can you figure it out yourself?” Even though the ban on the topic of prostitution was lifted from studio pictures in 1956 (Pennington, 2007, p. 110), Sunset Boulevard could never have made explicit any sexual relationship between Norma and Joe, since on-screen sex was still unacceptable under the code. Instead, the film asks the viewer to connect the dots, essentially posing the same question to the audience that Joe asks Betty: “Can you figure it out yourself?”

Tennessee Williams’s The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (Quintero, 1961) and Sweet Bird of Youth (Brooks, 1962) posed interesting complications relative to the code’s strict guidelines for Hollywood films. Both Mrs. Stone and Sweet Bird feature characters who, with only a small a mount of interpretive license, are gigolos satisfying older women in order to make a living. Sweet Bird of Youth, much like Sunset Boulevard, follows a young man, Chance (Paul Newman), who is trying to make it in Hollywood by “caring for” an older actress. Where Sunset Boulevard asks its audience to fill in the gaps, Sweet Bird makes the sex that has occurred between Chance and his benefactress, Alexandra Del Lago (Geraldine Page), clear. After a heated discussion between Chance and Alexandra, Alexandra walks to bed, saying, “I have only one way to forget the things that I don’t want to remember, and that way is by making love. It’s the only dependable distraction and I need that distraction right now. In the morning we’ll talk about what you want and what you need.” Chance responds, “Aren’t you ashamed a little?” “Yes, aren’t you?” replies Alexandra. Although it seems that Chance has avoided sex for compensation up until this point, he ultimately succumbs to an act that makes him feel ashamed.

Challenging Censorship

The work of American playwright Tennessee Williams often pressed the Production Code Administration (PCA) beyond any previous films in terms of adult themes. R. Barton Palmer (1998) cites A Streetcar Named Desire (Kazan, 1951) as a turning point in this respect. Palmer notes that, shortly before A Streetcar Named Desire, Bicycle Thief (de Sica, 1949) had been released in the United States without the approval of the PCA—a huge blow to the administration, in that the film went on to be “defiantly successful” at the box office. “After the Bicycle Thief embarrassment,” writes Palmer, “Breen [head of the PCA] could ill afford another public incident that suggested his office was narrow-minded in its opposition to modern art. Williams’s play, after all, had won the Pulitzer Prize” (p. 218). Even though these films were able to deal with male sex work, they sprung from the world of Broadway and literature, from a cultural form that “[catered] to a minority, elite culture.” This is exactly the kind of culture, however, that the PCA was beginning to fear censoring around the time of Streetcar. It is because of this precedent that, a decade later, Hollywood art films The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone and Sweet Bird of Youth, both penned by the critically acclaimed Williams, could be produced by major studios.5

Whereas Sunset Boulevard is unable to fully articulate the work that Joe Gillis is doing and the characters in Sweet Bird of Youth saw sex work as something of which to be ashamed, Andy Warhol’s My Hustler (1965) and Peter Emmanuel Goldman’s Echoes of Silence (1967) were some of the first American films to make their characters’ sex work an explicit and celebrated part of their story. Often discussed in relation to (and as a part of) the “highbrow underground art films” (Thomas, 2000, p. 69) of the 1960s New York avant-garde scene, these films broke ground in the filmic representation of the male sex worker. Working outside of Hollywood code-era restrictions and screening outside of mainstream venues,6 art films were free to experiment with both content and form in ways that exceeded the freedom of the Hollywood studios. My Hustler, for example, is roughly an hour long and comprised of only two shots—one on a Fire Island beach, and the other in the bathroom of one of its characters. During the shot on the beach, Warhol spends 30 minutes focused on the reclined body of Paul (Paul America), a hustler from “Dial-a-Hustler” who has been hired to service Ed (Ed Hood) on Fire Island. The camera makes rough, choppy pans between Paul’s body on the beach and a conversation occurring between Ed, Joe (Joseph Campbell), and Genevieve (Genevieve Charbon) in Ed’s beachfront home. The second shot of the film, which also lasts approximately 30 minutes, takes place in a private bathroom. In this shot, Joe and Paul take showers, shave, and get dressed while discussing hustling as an occupation (Joe is a semiretired hustler himself).

The rough camera work, 30-minute shots, and extended dialog allow My Hustler to “closely [resemble] a documentary film in its cinema verité style—a documentary of homosexual desire at one historical moment” (Escoffier, 2009, p. 26). This interest in documentary style has been praised by Joe Thomas (2000) for its “open representations of the eroticized male body presented within the relatively safe (for closeted gay viewers) context of avant-garde art” in a way that has been directly linked to the “formal and narrative models [of] the early days of gay porn” (p. 69). Early “porn filmmaking,” Jeffrey Escoffier (2009) explains, “included a strong documentary impulse—ultimately documenting and authenticating male sexual arousal and release” (p. 26), a goal that later became key to the New Queer Cinema movement as well.

Interestingly, these same concerns (and the work of Andy Warhol specifically) played heavily into the early films of Pedro Almodovar and the aesthetics of La Movida, Spain’s post-Franco youth movement of the 1970s and 1980s (D’Lugo, 2006, p. 18),7 and in the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the New German Cinema of the same time period. In fact, Almodovar’s “Warholesque interest in … male prostitutes and drag queens” (p. 19) has been cited as one of the main reasons for his “meteoric rise to international prominence,” in that it was able to “align the gay scene in Madrid with Warhol’s New York of the previous decade” (p. 19).8 Fassbinder, whose film Fox and His Friends (1975) deals with male sex work directly,9 also has been viewed in relation to Warhol’s work. In a 1975 review, Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson wrote, “It’s interesting that the true inheritors of early Warhol, the Warhol of Chelsea Girls and My Hustler, are in Munich” (pp. 5-6). They point to this “inheritance” in Fassbinder specifically, in that both Fassbinder’s and Warhol’s films “sprung out of a camp sensibility” that includes an appetite “for the outlandish, vulgar, and banal in matters of taste, the use of old movie conventions, a no-sweat approach to making movies, moving easily from one media to another, [and] the element of facetiousness and play in terms of style” (pp. 5-6), a connection that later was made explicit when Warhol crafted the poster for Fassbinder’s last film, Querelle, in 1982. In this way, the shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art cinema produced outside the United States was very much tied to the New York underground film scene and, in particular, the work of Andy Warhol.

While early films like My Hustler were groundbreaking in their representations of male sex workers, it was the release of Midnight Cowboy in 1969 that marked the first major Hollywood film (outside of the work of Tennessee Williams) to both feature male sex workers as main characters and allow them to fulfil their job description. Midnight Cowboy also was influenced by the work of Andy Warhol; in fact, director Schlesinger asked Warhol to make a cameo appearance in the film. As Warhol describes it, “Before I was shot, they’d asked me to play the Underground Filmmaker in the big party scene and I’d suggested Viva [one of the regulars in Warhol’s Factory] for the part” (Warhol & Hackett, 1980, p. 352). As Jody Pennington (2007) notes, “Among the novel qualities of many American films made during the period known as the Hollywood Renaissance,” of which Midnight Cowboy was a part, “was the routine inclusion of sexual behavior the Production Code had forbidden” (p. 52). Midnight Cowboy came at a time when Hollywood filmmakers were reacting to new freedoms that the studio system previously had limited due to the code. Thus it follows that subject matter from this postcode period that previously would have been unacceptable would emerge in film after a new rating system (the ratings G, M, R, and X) was established in 1968 (Casper, 2011, p. 119). Emphasizing the impossibility of creating a film like Midnight Cowboy during the code period, the film received an X rating.10

FIGURE 3.3

Andy Warhol created this movie poster for Querelle. He tied a shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art films produced outside the United States to the New York underground film scene, and to his own work in particular.

Reproduced with permission from the Artists Rights Society, licensor of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Copyright © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York.

This opportunity to present subject matter that was previously unacceptable did not go unnoticed at the time. Expressing his frustration and jealousy about Midnight Cowboy, Warhol (Warhol & Hackett, 1980) argued that what he and the New York underground film scene originally had to offer

was a new, freer content … But now that Hollywood—and Broadway, too—was dealing with those same subjects, things were getting confused … I realized that with both Hollywood and the underground making films about male hustlers—even though the two treatments couldn’t have been more different—it took away a real drawing card from the underground.” (p. 353)

“Perverse” Hustlers

Midnight Cowboy, which starred Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman as two sex workers living on the streets of New York, reflects a complex understanding of male sex workers, presented most often in flashbacks to Joe Buck’s (Voight) past. Yet the film also reflects the sense that homosexuality is perverse, which echoes the medical and sociological writings of the 1930s. Midnight Cowboy is a dramatic break from My Hustler, in that it presents the male sex worker in a way that he had never been seen before—as a central character in a Hollywood film—while maintaining much of the stigma that had surrounded the male sex worker for decades.

It is noteworthy, then, that the sociological and scientific discourse on male sex work during the 1960s and 1970s also had an interest in specific case studies of male prostitutes. Whereas Midnight Cowboy presented the face of male sex work as Joe Buck, John Scott (2003) notes that much of scientific discourse from the same period “was composed largely of individual case studies that sought to extract specific details concerning the aetiology of male prostitution and the identity of the male prostitute” in a way that “understood male prostitution in terms of sociopathology” (p. 186). Midnight Cowboy engages the subject of male prostitution similarly. By focusing on one specific sex worker, the film acts as a sort of case study, and through its use of flashbacks to childhood and adolescent trauma, Midnight Cowboy works to get at the etiological roots of male sex work. By using flashbacks to childhood trauma in moments of present trauma, the film creates a link that posits Joe Buck’s past traumas as the inciting events that determined his current occupation.

Like Joe Buck’s childhood and adolescence, homosexual sex (both in sex work and, more generally, in its characters’ lives) is a complex and difficult subject in Midnight Cowboy. Joe Buck comes to New York with the dream of becoming a male gigolo paid to have sex with women, but when times are tough and his career as a gigolo seems to be failing, he resorts to sex work for male clients. These encounters, which, in the words of Benshoff and Griffin (2006), are presented as “sick and pitiful” (p. 135), always end poorly for Joe. In his first homosexual encounter, Joe allows a young man to give him oral sex in the balcony of an old, run-down movie theater. The encounter ends in failure, as the boy has no money to pay Joe and Joe leaves empty handed. In his second homosexual encounter, Joe prepares to have sex with an older gentleman whom he “gratuitously beats … senseless” to get money to buy his friend a bus ticket (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). Joe does not appear to murder the client, who is speaking to his mother on the phone just before Joe beats him and, thus, is made to represent the “repressed homosexual,” but the brutality of this scene is unmatched by any other encounter in the film. In these moments, Joe is not the cocky young stallion he envisions himself to be when he is with older women. Instead, homosexual acts symbolize Joe’s descent into extreme poverty and desperation that escalate to his encounter with the older gay man, which is by far the most abject moment for Joe and the most difficult for the audience to watch.

At the same time, however, Midnight Cowboy provides a story in which its characters’ homo-social bonds foster their most productive relationships. Joe’s relationship with Rizzo (Hoffman), although platonic, is the “only genuine expression of love in the entire film … signaling the queer dynamic at work in the construction of male identity and male relationships” (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). As Joe travels to Florida with Rizzo at the end of the film, it is their relationship and Joe’s abandonment of his role as a sex worker that provide the hope for Joe’s future. In these moments, the film hints at a more complex understanding that breaks down the boundaries between homo-sociality and homosexuality but ultimately differentiates between homo-love and homo-sex—a sentiment that a Los Angeles Times preview article for Midnight Cowboy echoes, stating that the film exhibits a “tender story of a profound but not homosexual relationship” (Thomas, 1969, p. R22). Homo-sex (defined in Joe’s two homosexual hustling encounters) symbolizes abjection at its worst, while homo-love (defined by Joe’s relationship with Rizzo) provides an image of love at its purest; the boundaries are strictly maintained.

Perhaps the most direct articulation of George Scott’s notion of the homosexual hustler as sick, criminal, and perverse, in contrast to the heterosexual gigolo as rational, healthy, and virile, is Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo (1980). The film depicts a very rigid line between the homosexual sex worker and the gigolo, presenting its protagonist as the heterosexual stallion that Midnight Cowboy’s Joe Buck so desperately wants to be; a connection that Chicago Metro Times reviewer Rocsan Richmond (1980) makes perfectly clear when, in her review of American Gigolo, she writes, “I’d looked forward to seeing ‘American Gigolo’ ever since I’d learned of its subject matter a year ago … I was hoping [Richard Gere] might take over where Jon Voight left off in ‘Midnight Cowboy’” (p. 10). Julian (Richard Gere) is positioned in direct opposition to Leon (Bill Duke), the film’s antagonist, a homosexual pimp, which led to allegations that the film was homophobic (Mass, 1990, p. 4). For Julian (much like Joe Buck), homosexual sex work was a necessity at a certain point in his career but was never intended to be the end goal. While Midnight Cowboy shows its audience the desperation that leads Joe to take on homosexual sex work, American Gigolo provides the backstory that posits Julian as an ex-hustler who is now a successful gigolo. American Gigolo positions homosexual sex work as the bottom rung on the ladder one must climb to become a successful gigolo—a rung to which Julian never wants to return. He repeats time and again that he absolutely will not do that “fag” or “kinky stuff.” Julian has graduated from the world of the abject (gay/dirty/bad/kinky) into the world of the vanilla (heterosexual/clean/good/as close to heteronormative as possible).

New Queer Cinema: Renegotiating “Male Hustlers”

It was these notions of homosexuality as abject and of homosexuals as “repressed, lonely fuck-ups and/or killers” that gay filmmakers working during the 1970s and early 1980s were trying to combat. However, one of the main tenets of the gay rights movement was, as Glyn Davis (2002) puts it, “assimilationist,” in that the movement was interested in positive representations of gay characters that said “we are just like you, really, so please accept us” (p. 25). It follows, then, that gay activists would not be interested in (re)claiming the image of the male sex worker since he, by his very definition, is opposed to the homonormative idea that “we are just like you” (“you” being the imagined heteronormative ideal). In direct opposition to notions of heternormativity, New Queer Cinema (NQC for short) emerged on the film festival scene in the early 1990s. These films offered, according to B. Ruby Rich (2004), “something new, renegotiating subjectivities, annexing whole genres, revising histories in their image” (pp. 15-16). These films exhibit a trait that Rich calls “‘Homo-Pomo’: there are traces … of appropriation and pastiche, irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind,” which makes them “ultimately full of pleasure” (pp. 15-16).

Directly in the wake of and in response to the AIDS crisis (and the Reagan administration’s horrendous response to it), these films were no longer concerned with positive representation for gay individuals. NQC instead sought to “‘take back’ materials used by straight cinema—stereotypes, stories, genres—and in an anarchic, subversive spirit, rework them, and thus alter their social and political implications” (Davis, 2002, p. 26). These new gay characters no longer had to conform to the confines of traditional Hollywood representation, thus these films could feature characters that were previously unacceptable as protagonists, including the gay male sex worker.

At the same cultural moment that cinematic representations began to shift with NQC, the medical and sociological literature that dealt with the subject of male prostitution began to shift as well. In the 1990s, many studies were published that focused on the topic of male sex work—something the literature published previously never dared or felt compelled to do. All of a sudden, the male sex worker could not be summarized in a paragraph or a few pages; he demanded texts of over 300 pages in length, such as D. J. West’s Male Prostitution (1993), Peter Aggleton’s Men Who Sell Sex (1999), Samuel Steward’s Understanding the Male Hustler (1991), and Graham and Annette Scambler’s Rethinking Prostitution: Purchasing Sex in the 1990s (1997).

Many of these studies found their critical importance (or, perhaps, justification for being) in relation to the HIV/AIDS crisis, in much the same way as the films of the NQC; they also presented many of the same goals as NQC, foregrounding an interest in historical types, in reclamation, and in complication. More than a third of the essays in Men Who Sell Sex (Aggleton, 1999), for example, explicitly focus on the sexual risk of HIV/AIDS, while Scambler and Scambler (1997), in their afterword to Rethinking Prostitution, work to democratize sex work by noting that, in Britain, the laws have been historically “gender biased even in conception: there was a High Court ruling on 5 May 1994, for example, that only women can be charged with loitering under the Street Offences Act of 1959” (p. 180).11 Articulating the need to complicate traditional notions of male sex work, D. J. West (1993) writes:

Popular images of the male prostitute are confused and contradictory, poorly informed and often more concerned with moral condemnation than humane understanding … Prostitution is generally thought of as a woman’s occupation, but the “oldest profession” caters to all sexual demands and the desire of some men for sexual contact with their own kind has been known throughout recorded history … The assumption that women, including lesbians, have no need or no wish to pay men for sexual services has become less certain since the advent of the “toy boy” fashion, but young male prostitutes still seem to cater mostly to older males. (p. ix)

It is with this historical background, spanning from the 1930s to the 1980s, that films like Araki’s The Living End and Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho can be seen as revolutionary in their representations of male sex workers. While NQC presented numerous films with male sex workers as main characters within its formative years,12 these two films have been noted as being particularly emblematic of the NQC movement. These films appropriate the character types of male sex workers in Hollywood cinema (the “repressed, lonely fuck-ups and/or killers”) in a way that allows for and explores these characters’ complex relationships to sex work, which enables homosexual sex work and homosexual sex more generally to escape their earlier fundamental tie to abjection.

The Living End, which follows the road-trip adventure of Luke (a spontaneously violent, HIV-positive male hustler) and Jon (a recently diagnosed HIV-positive film journalist), provides a narrative trajectory in which its protagonist, Jon, can work through his HIV diagnosis in a way that allows him to be liberated “at a time where that health status appeared inevitably to lead to a rapid demise” (Hart, 2010, pp. 14-15). As Glyn Davis (2002) has discussed, Araki’s film directly references two particular types of gay men from traditional Hollywood filmmaking, the “macho” and the “sad young man” (p. 26). Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, on the other hand, tells the story of two male sex workers—Mike (River Phoenix), a homosexual hustler, and Scott (Keanu Reeves), a self-identified heterosexual who says he’s willing to “sell his ass” for money—as they embark on a road trip to find Mike’s long-lost mother. Mike exists as the “repressed” character type who longs for his mother, while Scott represents the “fuck-up” who sells his body as a way to rebel against his wealthy father. While each film has its own distinct cinematic style and its own seemingly contradictory message about male sex work, both strive to challenge the finite lines and simplistic notions that have historically classified male sex workers.

The complexity with which these films explore their characters’ sexuality becomes especially evident in their visualizations of gender performance, particularly in relation to the roles of women. Whereas Julian only sells his body to women in American Gigolo, My Own Private Idaho’s Scott keeps a clientele that usually consists exclusively of men. In his essay, Just a Gigolo? Paul Burston (1995) makes a compelling argument regarding Julian’s performance of heterosexuality, which is particularly interesting when considering the men of My Own Private Idaho. Burston argues that Julian is at home in a world of “sun-kissed bodies and swimming pools, of pastel interiors and micro-blinds … Framed within this world, Julian is coded as an object-to-be-looked-at … At the same time, the precise way in which he is coded for visual pleasure borrows heavily from a long tradition of homoerotica” (p. 115). The film works tirelessly to drain this “ambiguous eroticism” of its homosexual potential by having Julian constantly remind other characters and, thus, the audience that he doesn’t do “that fag stuff.”

In one of the film’s only sex scenes, Julian comes to a lavish home to service an older woman, but her husband, who is coded as a repressed homosexual (Burston, 1995, p. 116), demands to watch and instruct Julian as he works. The disgust that Julian exhibits at the thought of even being watched by a man places any sort of homosexual interaction (including the male-on-male gaze) as abject territory. As the scene progresses, the man commands Julian to “Slap her! Slap that cunt!” In these moments specifically, as well as in the film more generally, gay characters are shown to be excessively violent at the expense of the white woman. This man, whom the audience has identified as homosexual, demands that Julian beat his wife, while the other homosexuals in the film, Julian’s pimp and the pimp’s other gay male prostitutes, end up murdering this same woman and framing Julian, reinforcing the “homosexual killer” type and linking S&M sex practices to homosexuality and, ultimately, to murder. Julian has found himself in a situation with the two things he likes least—“fag” and “kinky stuff”—and where he is subject to both. Although the film’s poster for its recent DVD release features the tagline “HIS BUSINESS IS PLEASURE” in big bold letters, the audience is quickly reminded of the qualifications one needs to retain Julian’s services. This offer only applies if one is a woman, wealthy, white, and (usually) married. Men and/or sexual deviants (of any sort) need not inquire.

By contrast, the hustlers of My Own Private Idaho are open to having sex with anyone—male or female. In one scene, Mike is picked up by a woman in a new car. Dressed in his normal dirty clothes, unshaven, with messy hair, Mike is visually juxtaposed with his female client, who is dressed in a white fur coat and smoking a cigarette. As Mike says, she looks like she’s “living in a new car ad.” As they enter her lavish mansion, Mike comments that “this is like a dream. A girl never picks me up, much less a pretty rich girl.” As they enter her home, two more hustlers (one of which is Scott, Mike’s friend/crush) are sitting in the living room, waiting. Scott makes it clear, though, that she only has sex with one man at a time. “She’s cool,” he says, “she just likes to have three guys ’cause it takes her a little while to get warmed up. It’s normal, nothing kinky.” “Yeah,” Mike replies.

The idea of kinky sex doesn’t inhibit these characters, though; sex is sex and they’ll take the work where they can get it. Earlier in the film, for example, Mike has sex (of sorts) with an old dandy dressed in a suit with a bow tie, red hair, glasses, and a handkerchief. However, the “sex” the old man wants involves no sort of penetration. He wants to dance around his home, rubbing his feet against the floor while Mike cleans, making the space “immaculate” while dressed as a “little Dutch boy.” The film makes it perfectly clear that this is a sex act for the old dandy; as Mike scrubs the counters, the client rubs his own chest while moaning “faster, little Dutch boy, harder!”

Unlike Julian in American Gigolo, the hustlers of My Own Private Idaho are not averse to crossing the homo/heterosexual borders, nor are they inhibited by “weird” or “kinky” sex; in fact, there seem to be no real borders between hetero- and homosexual sex at all—both are legitimate parts of the same kind of work. In this way, the audience is never allowed to “identify Mike unambiguously, or unproblematically, as gay” (Lang, 2002, p. 249). Furthermore, Van Sant argues that “a person’s sexual identity is so much different than just one word, ‘gay.’ You never hear anyone referred to as just ‘hetero.’ That doesn’t really say anything … There’s something more to sexual identity than just a label like that” (cited in Lang, p. 251). The inability to define sexuality in simplistic terms is one of the base concerns of NQC, which embraces the fundamental complexity of the male sex workers’ sexuality.

While the sex act is never actually allowed to occur between the female client and Mike,13 the sense of abjection so present within traditional Hollywood representation is lacking within the fluctuation of sexual expression in My Own Private Idaho. Whereas the repressed homosexuals of films like Midnight Cowboy, represented by the man that Joe Buck beats senseless in a hotel room, are shown to be simply repressed homosexuals, Mike’s repression is a sign of his complexity. My Own Private Idaho understands repression as a character trait that exists beyond being a simple character type ready to be placed into a film without further explanation. Instead, Van Sant explores repression psychoanalytically. Linda Kauffman (1998) explains:

The film revolves around a search for origins (maternal, paternal, narrative), but the search is doomed to defeat … Whenever Mike falls asleep, recurrent images appear: he lies in his mother’s arms, infused with oceanic bliss … Mike’s narcolepsy is a symptom of his arrested development in the Imaginary; the recurrent images in his dreams are part of his “image repertoire.”(pp. 110-111)

One of the main tasks of My Own Private Idaho, then, is to work through the repressed homosexual, to understand and explore him and, therefore, to use the trait as a way to nuance the character type in a way that undermines the work of prior films with the same type.

Reinterpreting the “Hustler”

In an effort to recode, rework, and reappropriate historical understandings and history itself, both The Living End and My Own Private Idaho are concerned with placing their characters within and in reference to times past. The Living End’s Joe has just found out that he is HIV positive. After vomiting in the doctor’s office, he comes home, walks through the door, and pauses. Behind him is a poster for Andy Warhol’s Blow Job (1963). Mimicking the poster, Joe throws his head back and spreads his lips. The image behind is one of extreme pleasure while Joe’s expression is one of nihilism, expressing the pointlessness of life and emphasizing the words that Luke writes on a concrete pole in the following shot: “I blame society.” Wayne Koestenbaum argues that Blow Job is “a film of almost unbearable intimacy—unbearable, because one realizes watching it, that one has never before spent forty minutes without pause unselfishly looking at a man’s face during the course of his slow movement toward orgasm” (cited in Escoffier, 2009, p. 21). Blow Job, which is similar to My Hustler in style (Blow Job is comprised of one continuous shot), works to document lived experience. By calling upon the imagery of Warhol’s film (and, thus, a larger, internationally founded history of queer representation),14 Araki creates a moment in The Living End where the audience is asked to identify with a history and an emotion that exists beyond the confines of a single film. Where Warhol needed to document lived homosexual experience, Araki needs to document lived HIV-positive experience. Thus, The Living End could be discussed similarly as “a film of almost unbearable intimacy—unbearable, because one realizes watching it, that one has never before spent 85 minutes without pause unselfishly looking at two men’s faces during the course of their slow movement toward AIDS-related death.” As film critic Derek Malcolm wrote in a 1993 review of The Living End, “It’s what some of those Paul Morrissey/Andy Warhol epics of the sixties might have been had they become activated by the fear of AIDS” (p. 4).

My Own Private Idaho works similarly to interpolate and rework history as a part of its narrative. In one scene, a cowboy walks into an adult bookstore lined with porn magazines. As the fluorescent bulbs wrapped in pink gel flicker in the seedy, overpacked store, the camera tracks along the magazines, all of which have men on the cover. The camera finally lands on one called Male Call, and Scott, wearing a cowboy hat, his naked torso and unbuttoned pants made visible, adorns the cover. The magazine cover reads, “HOMO ON THE RANGE.” By utilizing the trope of the cowboy and recoding it within gay culture, Van Sant works to explode the mythology of American masculinity that is “inextricably bound to the image of the cowboy” (Kauffman, 1998, p. 108). As Scott explains his dreams of being a male model, he begins to have a conversation with Mike, who is the cover boy of another magazine, G-String, which is on the rack above Scott.

In the cover photo, Mike is wearing a white loincloth, his body draped over a vertical wooden pole in a position that recalls popular renderings of the Jesus figure. This posing of Mike has resulted in numerous critics deeming the cover “G-String Jesus” and noting that Mike’s pose “[evokes] the crucifixion” (Breight, 1997, pp. 307-308). The rack of magazine covers combines past and present in a way that “unites Rome, Renaissance England and modern America in a bizarre politico-sexual triad” (pp. 307-308)—a notion that the caption on Mike’s magazine, “GO DOWN ON HISTORY,” reinforces.

Both Scott and Mike (especially as portrayed by their magazine covers) draw on types of men that are summoned time and time again in the visual memory of heteronormative culture. The biblical reference to which Mike’s cover alludes, with his hands fixed up above his head and his nude body leaning backward (ribs protruding), recalls, recodes, and sexualizes the image of the nude body of Christ for homosexual consumption. Not only do these images of Mike and Scott suggest the homosexual potential in traditional icons, they make an explicit link between the male body, homosexuality, history, and male sex work.

New Queer Cinema did much more for the representation of the male sex worker than simply allowing him to be gay without being pathologized; it allowed him to be queer, and it suggested that he always had been. These films exhibit a notion of the queer body that, according to Michele Aaron (2004), sees queerness as

represent[ing] the resistance to, primarily, the normative codes of gender and sexual expression—that masculine men sleep with feminine women—but also to the restrictive potential of gay and lesbian sexuality—that only men sleep with men, and women with women. In this way, queer, as a critical concept, encompasses the non-fixity of gender expression and the non-fixity of both straight and gay sexuality. (p. 5)

Whereas one would assume that all male sex workers (even American Gigolo’s strongly heterosexual Julian) would exist outside of heteronormativity and would, therefore, on some level be considered “queer” under Aaron’s definition, pre-NQC cinematic representations of male sex workers (especially in American Gigolo and Midnight Cowboy) depict a world where male sex worker protagonists are as far from a notion of queer as possible. The most revolutionary element of NQC in relation to the depiction of male sex workers, then, is that the characters of films such as My Own Private Idaho and The Living End are not simply gay gigolos and they are not merely inversions of the traditionally acceptable male sex worker attempting to provide a positive image of a type of homosexual: they are queer individuals in a way that the protagonists of earlier films could never be.

The liberation and aggression with which these NQC films approached their subject matter, however, was not without controversy. When Araki described his work as not having “this propagandistic ‘It’s great to be gay’ outlook” in a 1992 interview in The Village Voice (Chua, 1992, p. 64), Adam Mars-Jones (1993), in a review for The Independent, saw this break from the desire for positive representation as a poor decision, given the timing of the AIDS crisis. “More than anything,” writes Mars-Jones, “it has been the catastrophe of AIDS, and the urgency of the despair it has brought with it, that has sparked ‘queer’ politics, and put patience out of fashion,” but, ultimately, “the AIDS crisis is a poor moment to pick quarrels” (p. 16).

Interestingly, both Gus Van Sant and Gregg Araki have dealt with the male sex worker in their later films, too, but in strikingly different ways. While Van Sant has gone on to alternate between directing mainstream films for major studios and his own independent works, he has continued to be the executive producer of films that explore queer identity.15 Incorporating the gritty aesthetic and aggression of the NQC, Speedway Junky (Perry, 1999, Van Sant executive producer) follows the story of a young man named Johnny (Jesse Bradford) who wants to become a race car driver as he falls in with a group of hustlers in Las Vegas. Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin (2004) poses a striking contrast to Speedway Junky. The film, which works through a narrative that could have been lifted straight out of an NQC film while appropriating a mainstream aesthetic, is about two teen boys, one of whom is a gay hustler, who are struggling to piece together their lives after their baseball coach had sex with them.

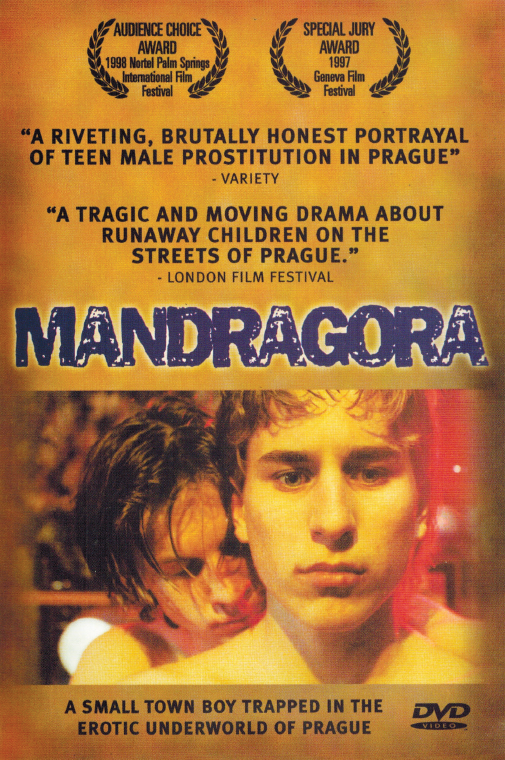

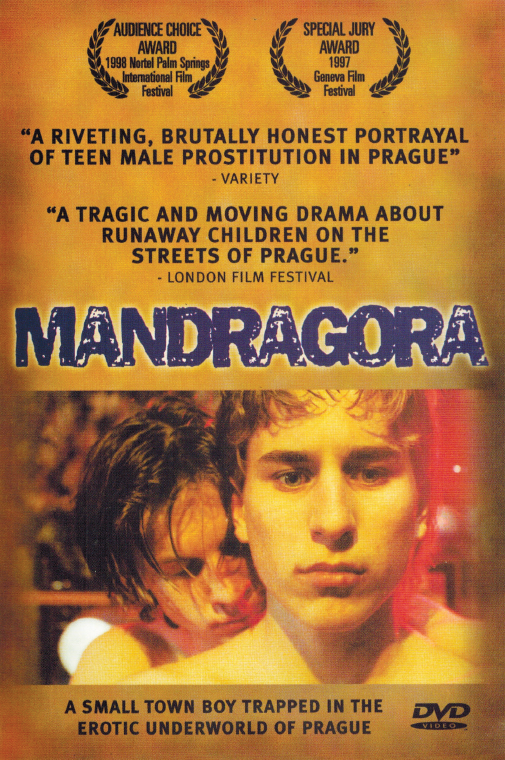

Post-NQC, the use of the character type of the male sex worker has flourished and become dramatically fractured. While major studio productions Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo (Mitchell, 1999) and The Wedding Date (Kilner, 2005) work to sanitize the gigolo, maintaining strict hetero-sexuality and presenting homosexual sex work as abject, Mandragora (Grodecki, 1997), Speedway Junky, Lola und Bilidikid (Ataman, 1999), L.I.E. (Michael Cuesta, 2001), Sonny (Cage, 2002), Mysterious Skin, Breakfast on Pluto (Jordan, 2005), and Boy Culture (Brocka, 2006) all have worked to push the male sex worker in a variety of other directions.

Mandragora and Lola und Bilidikid both grapple with male sex work in a way that echoes the work of the NQC. Robin Griffiths (2008) sees a strong parallel between the aims of Mandragora, which follows the rise and fall of a teenage hustler in Czechoslovakia, and the aims of the NQC. “Grodecki,” writes Griffiths, “was just as ground breaking in his unwavering yet ambivalent commitment to destabilize and subvert the heteronormatively inclined moral narratives, imagery and subjectivities that governed the more established tropes of Czech cinema and cultural production: confronting its entrenched stereotypes, assumptions and taboos even as he problematically re-inscribed them” (p. 139). While Mandragora ends tragically and ultimately works to reinforce notions of sex work as perverse, it deals with the AIDS crisis in a very visceral way.

In a scene of Mandragora in which Malek (Miroslav Caslavka), the film’s protagonist, and his friend David (David Svec) hire two female prostitutes to have sex, Malek is asked if he would like to have sex with or without a condom (there is a price difference). “You’re not afraid of AIDS?” Malek asks. “We’ve all got it anyway,” replies his companion. Where AIDS (and disease more generally) is never a concern for Deuce Bigalow or The Wedding Date’s Nick (Dermont Mulroney) and where The Living End’s Luke and Joe, in the height of the AIDS crisis, have been diagnosed with a death sentence, Mandragora’s sex workers are always already implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession. While issues of abject morality foreground many of the films that, either explicitly or implicitly, deal with male sex work pre-AIDS, films since the AIDS outbreak have fractured, dealing both with the moral implications of sex work and, frequently, concerns about health and disease. Where the dirty, run-down spaces of Midnight Cowboy historically symbolized abjection in regards to cinematic representations of male sex work, the bodies of the hustlers in Mandragora and The Living End have become a new site of concern.

Mandragora’s sex workers are always implicated in the AIDS crisis as a simple fact of their profession during the period of time in which the film takes place.

Aaron, M. (2004). New queer cinema: An introduction. In M. Aaron (Ed.), New queer cinema: A critical reader. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Aggleton, P. (Ed). (1999). Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV/AIDS. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Benshoff, H. M., & Griffin, S. (2006). Queer images: A history of gay and lesbian film in America. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Breight, C. (1997). Elizabethan World Pictures. In J. J. Joughin, (Ed.), Shakespeare and national culture. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

Burston, P. (1995). Just a gigolo? Narcissism, nelyism and the “new man” theme. In P. Burston & C. Richardson (Eds.), A queer romance: Lesbians, gay men, and popular culture. London: Routledge.

Casper, D. (2011). Hollywood film, 1963-1976: Years of revolution and reaction. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Chua, L. (1992, August 25). Low and inside. The Village Voice, p. 64.

Cresap, K. (2004). Pop trickster fool: Warhol preforms naivete. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Davis, G. (2002). Gregg Araki. In Y. Tasker (Ed.), Fifty contemporary filmmakers. London: Routledge.

D’Lugo, M. (2006). Pedro Almodóvar. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Epps, B., & Kakoudaki, D. (2009). All about Almodovar. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Escoffier, J. (2009). Bigger than life: The history of gay porn cinema from beefcake to hardcore. Philadelphia: Running.

Farber, M., & Patterson, P. (1975, November/December). Fassbinder. Film Comment, pp. 5-6.

Flexner, A. (1914). Prostitution in Europe. New York: Century.

Flowers, R. B. (2011). Prostitution in the Digital Age: Selling sex from the suite to the street. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Griffiths, R. (2008). Bodies without borders? Queer cinema and sexuality after the fall. In R. Griffiths (Ed.), Queer cinema in Europe. Bristol, England: Intellect.

Hadden, M. (1916). Slavery of prostitution: A plea for emancipation. New York: MacMillan.

Hart, K.-P. R. (2010). Images for a generation doomed: The films and career of Gregg Araki. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Kauffman, L. S. (1998). Bad girls and sick boys: Fantasies in contemporary art and culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kemp, T. (1936). Prostitution: An investigation of its causes, especially with regard to hereditary factors. Copenhagen, Denmark: Levin & Munksgaard.

Kuzniar, A. (2000). The queer German cinema. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lang, R. (2002). Masculine interest: Homoerotics in Hollywood film. New York: Columbia University Press.

League of Nations. (1943). Prevention of prostitution. Geneva: Author.

Malcolm, D. (1993, February 11). Films: The road to hell. The Guardian.

Mars-Jones, A. (1993, February 12). FILM/HIV positive role models. The Independent, p. 16.

Mass, L. (1990). Dialogues of the sexual revolution: Homosexuality as behavior and identity (Vol. 2). New York: Haworth.

Palmer, R. B. (1998). Hollywood in crisis: Tennessee Williams and the evolution of the adult film. In M. C. Roudané (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to Tennessee Williams. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Palmer, R. B., & Bray, W. R. (2009). Hollywood’s Tennessee: The Williams films and postwar America. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Pennington, J. W. (2007). The history of sex in American film. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Rich, B. R. (2004). New queer cinema. In M. Aaron (Ed.), New queer cinema: A critical reader. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Richmond, R. (1980, February 9). Fragmented story dilutes “Gigolo.” Chicago Metro Times.

Roudané, M. C. (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to Tennessee Williams. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Russo, V. (1987). The celluloid closet: Homosexuality in the movies. New York: Harper & Row.

Sanger, W. W. (1939). The history of prostitution: Its extent, causes and effects throughout the world. New York: Eugenics.

Scambler, G., & Scambler, A. (1997). Afterword: Rethinking prostitution. In G. Scambler & A. Scambler (Eds.), Rethinking prostitution: Purchasing sex in the 1990s. London: Routledge.

Scott, G. (1936). A history of prostitution from antiquity to the present day. New York: Greenberg.

Scott, J. (2003). A prostitute’s progress: Male prostitution in scientific discourse. Social Semiotics, 13(2).

Sikov, E. (1998). On Sunset Boulevard: The life and times of Billy Wilder. New York: Hyperion.

Steward, S. M. (1991). Understanding the male hustler. New York: Haworth.

Thomas, J. A. (2000). Gay male pornography since Stonewall. In R. Weitzer (Ed.), Sex for sale: Prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry. New York: Routledge.

Thomas, K. (1969, June 29). John Schlesinger, English film director, looks at U.S. Los Angeles Times, p. R22.

Warhol, A., & Hackett, P. (1980). POPism: The Warhol ‘60s. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

West, D. J. (1993). Male prostitution. New York: Haworth.

Woolston, H. (1921). Prostitution in the United States. New York: Century.

Movie titles, directors, year of release

American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980)

An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951)

Bicycle Thief (Vittorio de Sica, 1948; American release, 1949)

Blow Job (Andy Warhol, 1963)

Boy Culture (Q. Allan Brocka, 2006)

Breakfast on Pluto (Neil Jordan, 2005)

Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo (Mike Mitchell, 1999)

Echoes of Silence (Peter Emmanuel Goldman, 1967)

Fox and His Friends (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1975)

Howl (Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, 2010)

Hustler White (Bruce LaBruce, 1996)

Kids (Larry Clark, 1995)

L.I.E. (Michael Cuesta, 2001)

Lola und Bilidikid (Kutlug Ataman, 1999)

Mandragora (Wiktor Grodecki, 1997)

Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1969)

My Hustler (Andy Warhol, 1965)

My Own Private Idaho (Gus Van Sant, 1991)

Mysterious Skin (Gregg Araki, 2004)

Postcards from America (Steve McLean, 1994)

Querelle (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1982)

Skin & Bone (Everett Lewis, 1996)

Sonny (Nicolas Cage, 2002)

Speedway Junky (Nickolas Perry, 1999)

Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951)

Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950)

Super 8 (Bruce LaBruce, 1994)

Sweet Bird of Youth (Richard Brooks, 1962)

Tarnation (Jonathan Caouette, 2003)

The Killing of Sister George (Robert Aldrich, 1968)

The Living End (Gregg Araki, 1992)

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (José Quintero, 1961)

The Wedding Date (Clare Kilner, 2005)

Wild Tigers I Have Known (Cam Archer, 2006)