“I brought this on myself. It was my hubris. I was flattered by [Janis and Kurzman] and I fell for it. I was the first woman in the gallery and wanted to be with the boys. If I could get 31 Spring Street back, I would sell my walls or give them away.”

—Diana MacKown, quoting Louise Nevelson, as told to author, August 21–25, 2008

The year 1962 started out well for the artist. She was showing her work at Reed College in Oregon, where her old friend and former lover, art critic Hubert Crehan, was teaching.1 One of her large gold walls was shown in the Seattle World’s Fair, and the Los Angeles County Museum was installing some of her recent large black-and-gold walls in their newly opened Modern Art Galleries.2

Martha Jackson continued to act as Nevelson’s representative, though they had not been able to work out a contract that satisfied both sides and their professional relationship had ended on December 31, 1961. Martha Jackson did this out of friendship, but at the same time was protecting her sizable investment in the many Nevelson works she owned. In mid-February 1962 Jackson was overseeing an exhibition of Nevelson’s in Caracas at the Museo de Bellas Artes.

As much as Nevelson liked Martha Jackson and had been pleased by the growing number of museums and galleries in which her work had been placed by Jackson and Cordier, she had gradually become disgruntled by the pressures they were placing on her. Both dealers liked Nevelson’s large walls but ultimately found that the big sculptures were not so easy to sell as smaller works. According to Rufus Foshee, Jackson “would call Nevelson and say, ‘Louise why don’t you send me some small things that I can sell.’ Louise would retort, ‘You’re nothing but a goddamned rug salesman,’ and then hang up.”3

In addition Nevelson was not particularly happy with the way Jackson was physically handling her sculpture. While the artist always sent her work to the gallery using the finest art movers in the city, Jackson usually had her handyman, Buckley, return it to Nevelson in her station wagon. Nevelson could bear the minor humiliation of the humble transport of her work, but public embarrassment was not tolerable.

The end came in March 1962 when Jackson mounted an exhibition of Nevelson’s terra-cotta sculptures from 1938–48, sending out what Nevelson saw as a “very tacky notice to potential collectors.”4 Moreover, Jackson placed the works in the hallway of the gallery. Nevelson was convinced her new reputation as a prize-winning sculptor entitled her to a more distinguished location in the gallery. Despite Nevelson’s reservations, the terra-cottas were well reviewed. “It is difficult not to consider Nevelson’s early sculptures as precursors of her well-known black walls of boxes filled with wood-mill ends and other found objects, but they are beautiful in their own right.”5 Months later, in June 1962, her work would soon be shown at the Venice Biennale as one of four artists, chosen by Dorothy Miller of MoMA to represent the highest achievements of the United States in the visual arts.

On March 12, 1962, Nevelson’s lawyer, Elliott Sachs, wrote to Jackson stating: “The contract between Louise Nevelson, yourself and Daniel Cordier having expired on December 31, 1961, demand is hereby made on behalf of Mrs. Nevelson for the immediate return to her of all items held by you on consignment…. I have also been instructed by Mrs. Nevelson to advise you that the contract will not be renewed or extended.”6

On March 15, 1962, as she struggled to decide whether she had made the right decision about leaving Jackson, Nevelson had a dream about her current situation at the gallery and made some notes about it as if she were still able to report to Dr. Bergler, her psychoanalyst, who had unexpectedly died the previous month.

According to the notes, in the dream, she saw Martha in a restaurant, went over to her table, “kissed her and gently told her that my accountant just informed me that after all my expenses had been paid I was not making any money with her. All was gentle and sweet.”7 Later in her description of the dream, Nevelson lays out before Dr. Bergler Martha’s faults: Martha has been “ill and not in for three to four days to take care of the terra-cotta show”; “the catalogue for the show was ‘poor’ ”; “Martha couldn’t even sell Nevelsons to Seymour Knox, her wealthy childhood friend who had recently opened a major museum in Buffalo.”8 On the back of the notes about the dream, Nevelson scribbled the telling conclusion of the dreamer: “I want more freedom.”

As the recent patient of a Freudian analyst and a long-time adherent of Surrealism, Nevelson took her dreams seriously. What had been brewing beneath the surface of her friendly relationship with Martha Jackson finally burst out.

David Anderson refused to accept that Nevelson was going to end her contractual arrangement with his mother.9 Martha Jackson was more realistic and wrote to Nevelson’s lawyer about closing the Nevelson account. In May 1962 legal letters flew back and forth between Nevelson and the Martha Jackson Gallery winding up the many details about works still out on consignment at the Los Angeles County Museum and Pace Gallery. It would take many more to track down all the sculptures and make sure they arrived at the right destinations.

In June, David Anderson and Tom Kendall were to “take charge of getting back to her studio all works owned by her which are now consigned to us.”10 The final list was to be made ready for the lawyers at the end of July. In mid-July 1962 Nevelson had two lawyers trying to “wind up” her contract with Martha Jackson and get back the work Jackson had on consignment to museums and galleries, as well as “a complete accounting showing all moneys due to Louise and all pieces still on your premises which belong to Louise and which you are prepared to deliver to her.”11 But the works were not to be returned to her for a long time.

By the end of May, Nevelson had said her goodbyes to Jackson. In a waking version of her dreams, she gently kissed her dealer and “really good friend,” expressed her appreciation for all that Jackson had done to promote her career, but explained that her accountant had told her she was not making any money being represented by the gallery.

Being with Martha Jackson’s and Daniel Cordier’s galleries had lifted Nevelson up financially and professionally, and the arrangement had freed her to be productive without having to worry about her expenses. But pressure was constantly coming from Jackson or Cordier to make more black walls and to sell her sculpture whatever the size, which had never been the case with either Nierendorf or Colette Roberts.

At this crucial moment in her career she turned for help to a man whom she had known for a few years and trusted: Rufus Foshee. Nevelson knew that, as an independent art dealer at the Jackson gallery, Foshee had tried his best to sell her works. She knew that Foshee respected her, loved her work, and had bought as many of the pieces from Dawn’s Wedding Feast as he could afford—actually more than he could afford.

Her simmering disappointment with Martha Jackson had been stirred by Foshee, who believed the artist could do better. Foshee suggested that she meet with Sam Kurzman, a lawyer who specialized in art-world business, as Kurzman had helped an artist friend of his, Larry Calcagno, who was also showing at the Jackson Gallery. Events unfolded rapidly. When she first met with the lawyer, Nevelson did not know of Kurzman’s reputation as “a wheeler and dealer in real estate.”12 What she knew very well was that Kurzman was also gallery-owner Sidney Janis’s lawyer.

As Foshee’s version of the story has it: “Louise wanted to get free of Martha, and her contract had just run out. It was spring 1962. I called Sam and asked if he would represent and help Louise. He said yes, and Louise and I went to see him at home one evening. We had hardly sat down when Kurzman said he would get her into the Janis Gallery, and [just] as quickly Louise said, ‘And I will give you one my walls.’ ”13 Soon afterwards Foshee and Nevelson went to Kurzman’s home in Westport, Connecticut.

According to Foshee, “Sam and his wife Rose invited Louise and me up to Westport and insisted that we be their house guests. But Louise was much too smart for that. We stayed in a cheap motel. Driving up, she said, ‘I’m not looking for small stuff, I want the big fish.’ She meant that she wanted to move to the Sidney Janis Gallery.” Nevelson and Foshee’s visit to Kurzman in Westport set the stage for the coming disaster. Kurzman lived in a compound of four houses. His was the largest, sitting on a little knoll, and to the right of it was a smaller Cape Cod-style house. As part of the agreement to be represented by Janis Gallery, she agreed with Kurzman to buy the smaller house for forty thousand dollars, little knowing that it was not free and clear.

Nevelson had been hankering for quite a while to join the stars of the American art world—Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning—who had migrated to the Sidney Janis Gallery in the mid-1950s but were now on their way out. Before the meeting with Kurzman, she had not told Foshee about her long hoped-for plans. In much the same way as she had plotted and strategized to join the Karl Nierendorf gallery in 1941, she took her time figuring out what she wanted and waited for the right moment. When the right moment came—she leapt.

Without question Louise Nevelson was a careerist. She had devoted her entire life to her work and she believed that it deserved to be seen in the best possible setting. She had decided that she was finished with the Martha Jackson Gallery. She had ridden the crest of her recent popularity and landed Sidney Janis, the most prestigious dealer in New York—maybe in the world.

“Louise always wanted Janis,” Arne Glimcher later observed. “As soon as the Abstract Expressionist painters were with Janis, Louise wanted to be with him too. Going to Janis meant that she could be with the boys. Louise knew Janis had never had a woman artist, and that was a big point for her too. Janis Gallery wasn’t a better gallery than Martha’s. She [Martha]took care of her artists and was involved in their lives. Janis had great taste but was much more interested in the money and the names.”14

Before Louise Nevelson left for the Biennale, she had asked Arne Glimcher to meet her in Venice. Her reasoning made sense. By November 1961 Glimcher had sold approximately ten Nevelson sculptures he had on consignment from the Jackson Gallery, for approximately eleven thousand dollars. Nevelson had also heard that Glimcher almost persuaded the Boston Museum of Fine Art to purchase one of her large walls.

Glimcher remembers vividly his experience with Nevelson in Venice: “Louise liked me. I was young, and I was attentive, and she was always a flirt.”15 He recalls his experience with her in Venice:

Everything I knew about the Venice Biennale, Nevelson told me. “You should come with me,” she said and I went. Being with her was like a passport. I met many famous collectors.

I was considering moving Pace to New York, and in Venice she said, “Don’t worry. If you open in New York, I’ll be with you.” And then, “You’re going to be the king of the art world.”

I had placed ads in all the art magazines with an image of the Pace Gallery installation. Above it said, “Louise Nevelson at the Venice Biennale.” Under the photo, “The Pace Gallery.” When I got to London the week before Venice, I saw Erica Brausen, [director of the Hanover Gallery], and she assumed I was Louise’s dealer. “Can we do a show?” she asked. I said, “I think we probably can.”

She [Nevelson] had just left Jackson for Janis but in the interim everyone thought the Venice show was ours. Pace Boston suddenly became an entity because of the Venice Biennale and Nevelson. It was the first visibility for the gallery.16

Having seen the ads Glimcher had placed in art magazines, many Europeans already thought Glimcher was her dealer, as did some of the collectors who had been buying her work from Martha Jackson. When Erica Brausen saw Glimcher again in Venice, just before the opening of the Biennale, she introduced both him and Nevelson to her artists, chief among them was Alberto Giacometti. She was also friendly with Henry Moore, Henri Matisse, Francis Bacon, René Magritte, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, and Michel Leiris (whom she helped escape from Majorca during the Second World War).

Brausen’s gallery in London had become the premier place for modern art, and Brausen loved Nevelson’s work. She was eager to show it and work cooperatively with Arne Glimcher and proposed the idea of opening a gallery together, Hanover-Pace. For a young man just starting out, to be associated with such a prestigious dealer was a coup. But it wasn’t to be.

In June 1962, when they were both in Venice for the Biennale, it is unlikely that Nevelson had already decided to have Glimcher as her future dealer. But by the time they left, he was convinced that it was a done deal. In fact, on his return from Venice, he told his wife that when he moved his gallery to New York—his plan at the time, but an event that was still over a year away—he would have Louise Nevelson as his most important artist.17

During the summer of 1962 the world might have seemed unreal to Louise Nevelson. Her reputation and financial status had reached new heights. Only months earlier Dore Ashton had written in The Studio that, “One of the wealthiest imaginations working is Louise Nevelson’s.”18 The exhibition of Nevelson’s walls at the Los Angeles County Museum was well reviewed.19 She could have felt as optimistic as Icarus flying toward the sun. But the crash of the high-flying artist was coming soon. Her waxy wings were not as sturdy as she thought.

The story of Nevelson’s arrival in Venice and the lost suitcase that contained the outfits—her “Chinese robes”—she had wanted to wear for the opening and parties20 was intimately tied to her participation in the Biennale. As described in an earlier chapter, when the airline was not quick to retrieve her lost luggage, Nevelson announced that the suitcase contained the white wedding dress that she need for her marriage “on Monday,” the actual opening of the exhibition. Two years earlier she had used the same metaphor of marriage when Dorothy Miller had invited her to fill a large room with her sculpture at her first exhibition at MoMA, Sixteen Americans. The metaphor then was public and notable—Dawn’s Wedding Feast. In Venice it was more hidden, but for the artist it was the same union of her art with the world.

The original plan for Venice was to exhibit black, white, and gold sculptures owned by the Martha Jackson Gallery, along with some of Rufus Foshee’s white works from Dawn’s Wedding Feast. But an unexpected snafu with shipping occurred: The Museum of Modern Art had just changed its policy and wouldn’t pay the cost of shipping the pieces to Venice. At the last minute, it was decided to exhibit works already in Europe—owned largely by Cordier and currently traveling to exhibitions in Germany after the show in Baden-Baden.

As Dorothy Miller recalled: “For Venice we commandeered the work from [the touring show] and used it as raw material. A million boxes came in, and were sitting on the floor, while we flushed the ants out of the building and put up new ceilings. And then Nevelson just went to work with the Italian workmen and put up a new design. It was quite wonderful.”21

Nevelson thoroughly enjoyed installing her show with the Italian workers. “I didn’t speak any Italian, and they didn’t speak English. But it was a joy. Because of their efficiency and empathy to compose with me right there.” Using work from the travelling exhibition, Nevelson wrote in her autobiography, “I composed environments that had never been seen before.”22

Maryette Charlton. Louise Nevelson, Alberto Giacometti, and Dorothy Miller, at the American Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, where Miller was installing Nevelson’s work, 1962. From the Maryette Charlton papers, ca. 1890–2013, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Maryette Charlton

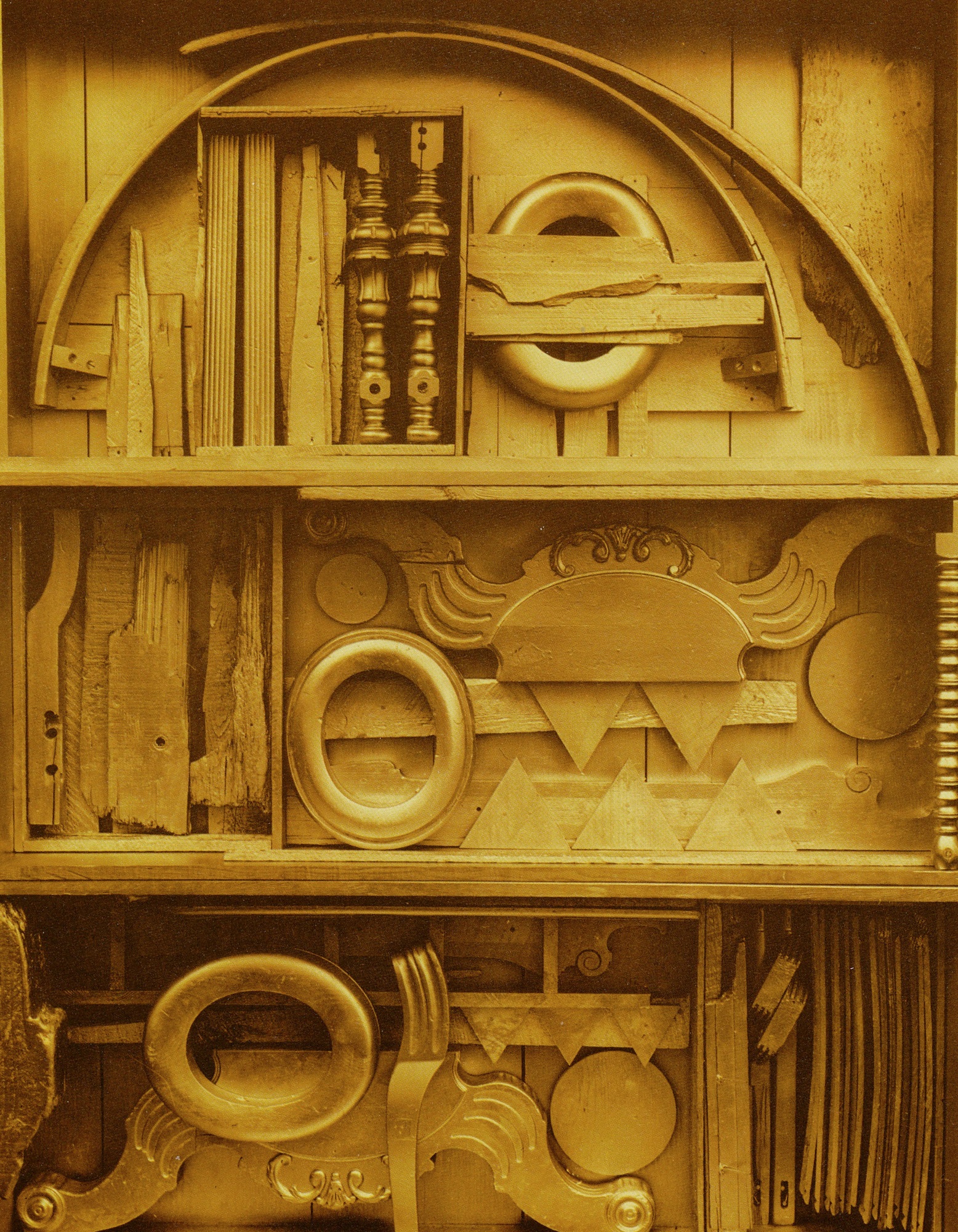

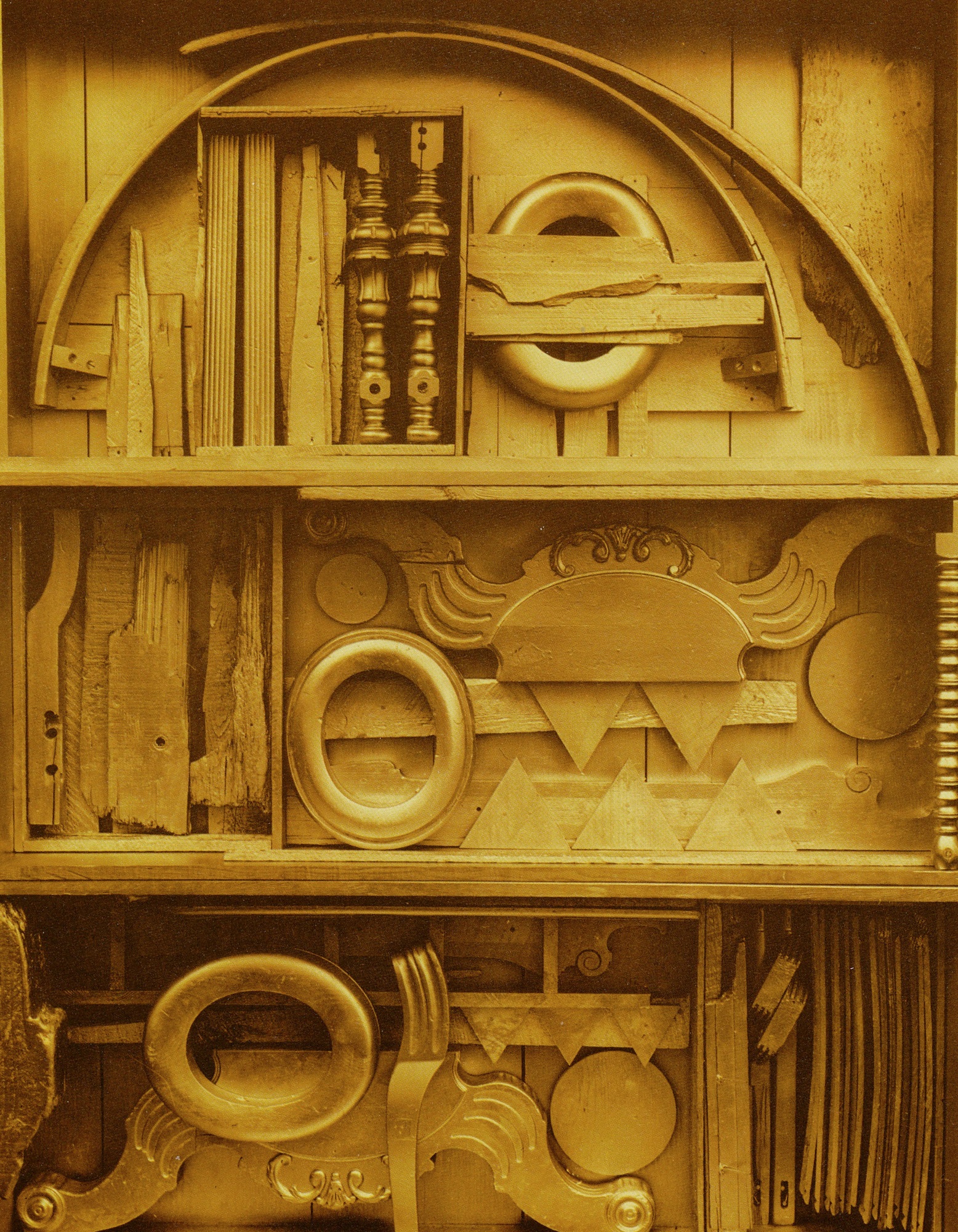

The artist had been given three large galleries at the Biennale. She painted the circular entrance room gold and filled it with her gold-painted sculpture. On the right side, called the camera oscura by locals, were her black-painted walls. On the left, she had created a wall of white sculpture, which she named Voyage 1962. She covered the glass ceilings of each of the lateral rooms with black or white fabric to match the sculpture.

Though Giacometti won the grand prize for sculpture in Venice, he claimed that Nevelson deserved it. According to Nevelson, “He went to great lengths to explain to [a dealer from Paris] how [Nevelson’s work] was sculpture … a new form. He was very pleased with it.”23

The catalogue essay for the Venice Biennale, written by William Seitz, shows the high regard the MoMA curators had for Nevelson’s contribution:

[Louise Nevelson]’s newer work—especially the unusual “Walls” … are dominating environments to which a spectator must adjust.

The tall [white-painted] Cathedrals [have] an austere ceremonial presence…. In works painted black, families of disks, rectangles and sticks, recede into darkness. Surface becomes light and splendor on the walls of gold; they are devotional or regal in mood, recalling St. Mark’s, Burgos or Versailles. White, black or gold, the homogeneous coating seems to transform crude elements into a new substance. It is such transcendence toward which Nevelson aims.24

Seitz, along with several astute critics, emphasized the transcendental spiritual quality in Nevelson’s walls. Michel Ragon, one of the main critics of Cimaise, refers to Nevelson’s three rooms as, “A trilogy which surpasses competition…. With wooden débris … Nevelson raises great altars as rococo as those of Mexico and Spain…. One could pray before Nevelson’s altars (yes, these are altars, shrines, relics of pioneer America).”25

The reviewer for Art News, Milton Gendel, wrote that, “most impressive [works at the Biennale] are Louise Nevelson’s three room-sculptures in white, gold and black, which are like chapels for the cult of the object. The sawn and found pieces of wood are composed, framed and built up into an overwhelming fantasy architecture that arouses the esthetic desire of I-wish-I had-thought-of-that.”26

In contrast to Seitz, Ragon, and Gendel, other critics thought the hyperbole was “disproportionate” and asked: “Can such nonsense be taken seriously?”27 The reviewer for L’Oeil, Guy Habasque, noted that “the success of this artist and the abundant literature that it has engendered forces us to see her work as something beyond a perfected game of cubes.” And he thought it was “unrealistic” for Seitz to have compared her walls to St Mark’s, Burgos or Versailles.28 Meanwhile, Robert Melville, an English art critic who had loved her work when he had written about it in London less than a year earlier, reversed himself. He ended his review: Nevelson’s work is “a monument to what I suppose to be [her] loss of faith in everything except her own compulsive activity, and it’s appropriate that an artist from the country that has the biggest dumps of discarded objects in the world should out-Schwitters Schwitters.”29

With this mixed response from critics, it is easier to understand why Nevelson seemed out to sea on her return from Venice. The critics had tossed and turned her—some highly praising her rooms as the most sensational feature of the entire Biennale, but others damning her work as tawdry, repetitive, and self-aggrandizing.

Rufus Foshee tells the story of another meeting with Kurzman just before Nevelson and Dorothy Miller had left New York for Venice in early June of 1962:

The day Louise left for Venice, Sam came to 29 Spring Street …. I was there—Louise did little in those days that I was not included in. We sat down to the dining table. It was agreed that Janis would give Louise $60,000 year. Unlike the deal with Martha, there was to be no contract. Kurzman said Janis did not do contracts. I remember that Louise was given her first advance by the Janis Gallery that day as well—and I think you will find that check for $20,000 in Janis’s records—another due maybe in October. At that same meeting Sam said he was taking back the mortgage on the Westport house, and Louise was to pay him $l57 a month. (I may be off fifty cents, but doubt it.) ….30

All the arrangements were made for what Sam perceived as his control of Louise’s life forever. He just did not know with whom he had locked horns. Those checks were written for $157 plus, and more than one, I expect for at least the rest of 1962. Once all the business had been taken care of, we got in a cab and went off to the airline terminal where we met Dorothy Miller. That was the last peaceful moment any of us was to have for years.31

“Louise was so well-grounded, I had never seen her nervous. But when she came back from Venice, she was shaken…. She lay in her bed speechless, without moving,”32 her old friend Marjorie Eaton observed. According to Rufus Foshee, “Almost everything went wrong after she returned. As close as I was to Nevelson, it was still difficult to know what was happening. I think two things took place. Her new dealer, Sidney Janis, decided that he liked her white sculpture more than the black or gold and, second, he and his lawyer Sam Kurzman decided they wanted Louise under contract. There was an ‘important’ meeting at Sam’s where they got her to sign an exclusive contract.”33 Neither Foshee nor Nevelson had any idea how bad a deal she had signed. The house in Westport, which Nevelson now “owned,” had a lien on it, so it was never actually hers.

By late September, realizing that she wouldn’t live in the “the fancy house” in Westport she had bought from Kurzman, she invited her son Mike to move there from Rockland. By the beginning of October he had sold his house and studio in Maine and transported his family to Westport, having no understanding of the complicated mess in which he was now involved. Mike was planning to use the profit from the sale of his Rockland property to invest in a proper studio in Connecticut. He found a modest place in New Fairfield and started to fix it up.

Foshee later recounted: “As fall approached, one cold rainy Sunday afternoon,”

Nevelson called and said she needed to see me. I got there and she was in a state. Janis had not produced the rest of the money he had promised her as an advance. She asked me to go see Sam and make it very clear that no work would be sent to Janis for her show unless she had the money. What a fool I was. But loving her work, I did it. And after all, who was I? I was thirty-one, with no credentials. I delivered the message in person to Sam in blank language. The money arrived. It probably would have been best had that exhibition [at the Janis Gallery] not taken place, but it did.34

In August, Jackson was putting out press releases announcing that Nevelson had won the grand prize (three thousand dollars) in the First Sculpture International of the Center of Visual Arts of the Torcuato di Tella Institute, in Buenos Aires. Later that month, Seymour Knox paid the Martha Jackson Gallery six thousand dollars for Nevelson’s gold-painted sculpture, The Royal Game, which he gave to the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo. The sale was the subject of a Time article titled “All That Glitters.” Calling her a “scavenger-sculptress” and describing in detail the artist’s gold studio and recent achievements, the critic concludes: “She is at the height of her fame, sales of her work last year amounted to about $80,000, and in the fall she will change galleries to become the first woman and the first U.S. sculptor to be handled by Manhattan’s choosy Sidney Janis. For Louise Nevelson, the future looks golden.”35

During the second half of 1962 Janis was in dispute with both Nevelson and Jackson about the ownership of Nevelson’s sculpture. At the same time Arne Glimcher and Martha Jackson were still trying to sort out their respective Nevelson holdings. (Glimcher had on consignment a total of seven sculptures consisting of thirteen units.) Nevelson had signed her contract with Janis, and he simply assumed that whatever Jackson had of Nevelson’s work belonged to him. Before the opening of Nevelson’s first show at his gallery on New Year’s Eve 1962, Janis made sure that the sculptures still on consignment to Martha Jackson had been transferred to him. And Sam Kurzman made sure that Dawn Light I, the wall Nevelson had promised him months earlier, was delivered to his house.

Arne Glimcher did not intend to be forgotten in the confusion. As he continued his courtship of Nevelson, he was in the process of moving his gallery to New York. He had hoped that he could open in New York with a Nevelson show in the fall of 1963, but neither he nor Nevelson was ready for that. In the meantime, he offered Mike Nevelson a three-man sculpture show in Boston in collaboration with Mike’s gallery, Staempfli.36 A few days before the opening at Janis, Glimcher sent her a note:

Milly, Mother and I wish you … success in your new exhibition and know that you will have it, as you so richly deserve it. I have been in New York several times this winter but haven’t wanted to bother you, as I know how hard my favorite sculptor has been working…. We will be with you in spirit and share in your happiness, as happiness is what I want most for you…. Arnold37

For her solo show at Janis the artist had once again made three rooms with three different colors: Night Garden in black, Dawns in gold and New Continents in white. But what had been acclaimed at her first solo European show at Cordier’s in 1960 in Paris and at Martha Jackson’s Royal Tides in 1961 now drew decidedly mixed responses from the critics, as it had in Venice. Some, like Hilton Kramer in The Nation, gave her fulsome praise combined with a bit of focused criticism. He did not like the way Janis had installed the works. “No effort has been made to turn the gallery itself into a macrocosmic statement of the sculptor’s overall conception; each work stands separate and aloof as a discrete entity.” Kramer had a clear understanding of Nevelson’s vision of her sculpture as an environment. Furthermore Kramer didn’t like the white- and gold-painted work. His explanation was persuasive: “A development which admirers of Mrs. Nevelson’s work have found hard, perhaps impossible, to reconcile to the high standard of her own best work [is] the substitution of white and gold paint for the exclusive and integral use of black.” Without black, Kramer argued, “her essential sculptural idea, so heavily dependent upon the articulation of light and shadow, could not be realized.” Innovation, in this context, was not necessarily a good thing, and, he continued, “gold paint has the additional defect of degrading the whole work with an air of artificiality and specious glamour.”

Despite his criticism, Kramer ends with a powerful endorsement of Nevelson’s work and its place in art history:

Her achievement as a whole is nonetheless a large one. The new black wall in the Janis show is, like its predecessors, a kind of anthological summary of the whole Constructivist tradition. Memories of Arp and Schwitters live on easy terms with Cubist severities and anti-art hijinks; a tight Mondrianesque precision cavorts freely with Expressionist enthusiasms…. Mrs. Nevelson has mastered a complex tradition, and left it transformed.38

Colette Roberts, who remained a fervent devotee of Nevelson and her work, sent the artist a rough translation of the review she wrote for France-Amérique. Roberts’s encomium begins forcefully: “The expression of genius is possibly order in the very midst of disorder. What strikes when one enters the Janis Gallery is Order, a completely Nevelsonian order, where abundance, condensed this time, seems to have expressed itself by the excellence of detail as well as the excellence of the whole.” Roberts then took up a side of Nevelson rarely mentioned by American critics: the “mystical dimension” of her work and its “deeply religious overtone.”39 Roberts always understood and respected, more than any of her other dealers, the spiritual side of Nevelson and her work.

Brian O’Doherty of The New York Times wrote a mostly scathing review: “Louise Nevelson, exhibiting for the first time at Janis Gallery, showed three rooms of her wooden doodles.”40

Worse yet, her friend and former enthusiast, Dore Ashton now seemed to have doubts. Though she pointed out what was new—the regularity of the pre-made boxes of equal size, a feature that would become a consistent part of Nevelson’s future work—Ashton noted that she didn’t much like it. “The vertical-horizontal regularity of her divisions appears now to inhibit Nevelson’s fantasy, constraining her to choke each composition and without an impulse to break out into three-dimensional space.” Finally, she made clear that she was tired of white and gold—“black is always her forte.”41

Most of the walls Nevelson had made when Martha Jackson was her dealer contained boxes of different sizes, which she would put together in various formats. Three large walls, all made in 1962, in three colors, consisting of equal-size boxes—Dawn, New Continent, and Totality Dark—were a metaphorical punctuation mark indicating the end of a stylistic phase. The regularization of the containers was the beginning of a subtle but significant change in style.

The show that opened on December 31, 1962, was Nevelson’s only exhibition at the Janis Gallery. The weather that night was freezing cold, it was a holiday, and few serious collectors or art lovers showed up. When the exhibition closed at the end of the month, nothing had sold. It has gone down in (art) history as a disaster for both the artist and the dealer.42

Nevelson and Janis clashed almost immediately afterwards. She wanted out of her contract and to have all her work back, especially the three walls from the recent exhibition. Janis refused, claiming that she owed him the advance he had given her in the fall—at least $12,500, which was long gone.43 He kept her work hostage in storage. There seemed no way out of the legal and financial impasse, complicated as it now was by the real-estate deal with their mutual lawyer Sam Kurzman.

Kurzman continued to demand the monthly mortgage payments, which Nevelson could not afford, and threatened her with foreclosure. In the months to come she sold back to the previous owner the two houses on Spring Street where she had been living and working (the owner agreed to let her remain on a rental basis), but the amount was still not enough to satisfy her debt to Kurzman.

The house debacle would eventually be resolved at the end of the following year, when Nevelson won her case in court. But until that happened she went through hell. She had to contend with three different dealers. Extricating herself from Martha Jackson was complicated by their friendship and the accounting mess created largely by Jackson’s son, David Anderson. Jackson and Glimcher were still sorting out their Nevelson holdings. Glimcher also had his eye on a future contract with Nevelson, which couldn’t occur until she was totally free of Janis, who was holding onto her work.

Nevelson’s awareness that she had created the messy legal situation in which she now found herself did not make it easier. She stopped working, started drinking, and went into a downward spiral of depression from which she could see no escape.

Her faithful assistant Teddy Haseltine was no longer much help, since he too was deteriorating daily. Nevelson knew that Teddy’s depression and heavy drinking had to do with his being separated from his boyfriend, Al Argentieri, whom he saw mostly on weekends. A year earlier she had been discussing her concerns about Teddy’s neurotic behavior with her psychoanalyst and had figured that having another person in the house to keep him company might be useful. In February 1963 Teddy introduced Nevelson to Diana MacKown, a recent graduate of the MFA program at Yale School of Art and Architecture, where she had studied with Joseph Albers, a great fan of Nevelson. Soon after her first visit, Nevelson invited MacKown to move in, and she quickly became studio assistant, guardian, and all-around helper. Both Teddy Haseltine and Diana MacKown believed in the world of spirituality and served Nevelson as faithful companions on her voyage to the fourth dimension. They also played poker for pennies with Nevelson and her sister Anita, who by now had moved into the second-floor studio.

Nevelson drank, drank some more, and walked around the street at three in the morning, wondering if she was going to survive. Her high-flying career had taken a nosedive, and her usual remedy for depression—work—now complicated by financial and psychological entanglements, was beyond her reach.

Watching from a distance, some envious fellow artists who had never risen as far as Nevelson took comfort in her fall. Nobody loves a loser, and it appeared that Louise Nevelson had lost everything. Art-world people saw her coming and crossed to the other side of the street to avoid her. Many critics who had supported her for years agreed that the gold-painted works were trashy, brassy, and over the top; they didn’t discriminate between the good ones and the less good ones—they simply turned away. Nevelson was angry about the recent setbacks but especially angry at herself for having walked into a trap of her own making—her desire to rise yet higher than she already had—her hubris.44

Though Nevelson had moved away from Jackson by signing with Janis, Martha Jackson still owned a large amount of Nevelson’s work, and it was in both women’s interest for Jackson to continue exhibiting it. She began to plan for an exhibition of Nevelson bronzes cast from wood sculpture in late spring of 1963, and in the fall she included Dawn Light II in a show titled Eleven Americans. Perhaps the most significant help Martha Jackson gave to the beleaguered artist was helping her get away—far away—for a while.

In April 1963 Jackson helped arrange an invitation for Nevelson to spend three months making lithographs at June Wayne’s Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. “The Tamarind Workshop is thrilled to hear that you are definitely coming,” Jackson wrote. “It will be so interesting to see your recent discoveries translated into the graphic media. Jean Lipman says that Art in America will be most interested in publishing an article on your graphics, and she wants to be sure that she is the first person to see them on your return from California.”45 As Nevelson later put it: “I wouldn’t ordinarily have gone. I didn’t care so much about the idea of prints at that time but I desperately needed to get out of town and all of my expenses were paid.”46

Nevelson and her sister Anita went to Los Angeles in April 1963, and their youngest sister Lillian came a bit later for a visit. While she was in California, Mike Nevelson took care of things for his mother in New York, driving down from Connecticut to visit her Spring Street houses, “which appear to be in good condition,” and checking up on Teddy, who, he reported, “seems calmer and saner than usual.”47 Mike Nevelson was proud of being able to help his mother at such a difficult time. It fit with his sense of himself as the happily domesticated paterfamilias and accomplished artist—a Nevelson male who could help out a suffering Nevelson female.

By May, Nevelson had settled into her work at the Tamarind Workshop, and Martha Jackson was writing short, chatty, supportive letters, with news about possible buyers of her work to “Dearest Louise.”48

These letters make it clear that Jackson was still representing Nevelson, even though Nevelson was still under contract to Janis. There may have been some legal concern about Jackson’s selling Nevelson’s works to anyone, but that didn’t stop either of these determined women.

After thanking her for a recent check, Mike Nevelson wrote to his mother in late May that, “Ted seems more sane and responsible than ever!”49 Evidently acting on the advice of Nevelson’s new lawyer, Harris Steinberg (an art lover whose only requested fee would be one of Nevelson’s sculptures), Mike had decided to move his family out of the Westport house, which they would then return to Kurzman in order to settle up the bad real-estate deal his mother had made the year before. That transition was not going smoothly, since Mike’s new house in New Fairfield was not ready, and Kurzman had rejected his request to stay a few extra months in Westport.

Furniture and Girl (childhood drawing), ca. 1905. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Betty Estersohn. Marjorie Eaton with Nevelson’s Goddess from the Great Beyond, 1977.

York Avenue, New York City, 1933. Oil on board. Farnsworth Art Museum, bequest of Nathan Berliawsky 1980.35.21

Winged City, 1954–55. Painted wood, 36 × 42 × 20 in. Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Mildwoff through the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors

Walter Sanders. Louise Nevelson poised amid her environmental installation called Moon Garden, 1958. LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Royal Game I, 1961. Painted wood, 69 × 51 ½ × 8 ¼ in. Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1962 K1962:9

Sky Covenant, 1973. Cor-ten steel, 240 × 264 in. Temple Israel, Boston. Photograph by author

Untitled (collage), 1972. Paper, mechanical reproduction, pastel, metal foil, and embossed stamp on paperboard, 30 × 20 in. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1979. Photograph by Lee Stalsworth

Sky Tree, 1977. Cor-ten steel, 54 feet tall. Embarcadero Center, San Francisco. Photograph by author

Transparent Horizon, 1975. Cor-ten steel, 240 × 252 in. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Photograph by author

Hans Namuth, Portrait of Louise Nevelson, 1977. Photograph by Hans Namuth. © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate. Courtesy Hans Namuth Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

Photographer unknown. Cover of April, 1972 issue of Intellectual Digest.

Charles Moore. Cover of January 24, 1971 issue of New York Times Magazine. © 1971, The New York Times

Grapes and Wheat Lintel (Chapel of the Good Shepherd, Saint Peter’s Church), 1975. Painted wood, 43 × 94 × 3 ½ in. Photograph by author

City on the High Mountain, 1983–84. Painted steel, 246 × 162 in. Purchase Fund © Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York

Diana MacKown. Louise Nevelson at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1980. Courtesy of Diana MacKown

Volcanic Magic XVI, 1985. Wood and paper collage, 40 × 32 × 4 ¾ in. Farnsworth Art Museum, Gift of Louise Nevelson 1985.23.26

Iron Cloud or Sky Horizon, 1984–86. Cor-ten steel, 354 × 204 × 120 in. Gift to the National Institute of Health by John, Peter, and Susan Whitehead, the family of Edwin C. “Jack” Whitehead. Photograph © Roxanne Everett/Lippincott’s, LLC, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Diana MacKown. Louise Nevelson at Berliawsky-Small Cemetery, Rockland, ME, 1985. Courtesy of Diana MacKown

Diana MacKown. Louise Nevelson with Willem de Kooning, 1986. Courtesy of Diana MacKown

Diana MacKown. Louise Nevelson with Virgil Thomson and Edward Albee, 1984. Courtesy of Diana MacKown

Portrait of Diana MacKown, begun 1960s; completed 1983. Collage: Oil paint, fabric, mirrors, and cardboard, 26 ¼ × 62 ½ in. Courtesy of Diana MacKown

Steinberg was negotiating for Nevelson with both Janis and Kurzman, and so far the only “deal” Janis had offered was to agree to let her out of her contract for twenty-five thousand dollars. Nothing was mentioned about the return of her sculpture. Nevelson refused his deal. Nevelson was due to pay Kurzman back $20,800 on the mortgage note in June. Additionally, Kurzman was claiming that “young Mr. Nevelson” had no right to be in the house and demanded that he “immediately vacate the premises.” Mother and son were waiting for their lawyers to resolve the many problems and knew that “a long and costly court fight” was probably the only way to settle the madness.50

The Tamarind Lithography Workshop turned out to be ideal for Nevelson’s rehabilitation. June Wayne noted that, when Nevelson came to Tamarind, “She was quite distraught. And here, she comes to a place she’s never been, meets people she doesn’t know, and she is the total center of everybody’s attention. The entire crew was focused on making her art. She had nothing to do except be who she was and to work in the studio…. I was a little on the strict side with her during the day,” Wayne remembered,

because we could not afford to have an accident in the workshop. Not when you’re fooling around with thousand-pound stones and presses. So she wasn’t getting any booze during the day. But she would drink heavily at night…. And sometimes by the end of the evening, her breath would be strong enough to wither my eyebrows…. Well, she would be like any drunk—bleary, her language would be blurry. She might not really be responsive. You might have to herd her into an automobile. She might put her head on your shoulder, and then, as I said, the smell would be very unpleasant. She was clearly suffering. It was like she was ill.

I really never left her alone. And Louise needed not to be alone. I had no way of knowing that, but you sense it when you work with people the way we worked at Tamarind…. And she would work very hard, very inventively. She was not verbally talented. There was a great deal of gesturing and she could not necessarily explain exactly what she wanted. If you had a tape of what she was saying, you might be quite befuddled…. Louise often said to me that Tamarind saved her life. [For years afterwards] we spoke to each other, sometimes for an hour or more on Sunday mornings, when she would confide to me her newest problem, whatever it happened to be.51

During her first stay at Tamarind, Nevelson produced just under one thousand lithographs. These are not Nevelson’s best work, but they liberated her, and the kind treatment she received from June Wayne and the workers at the lithography studio made her feel at peace again. She had started her visit wearing her usual exotic outfits and makeup, but by the end she had shed her mask and comfortably worked in conventional clothes without any makeup. By the time Nevelson returned from Los Angeles to New York she had regained her sense of herself.

Marvin Silver. Tamarind Lithography Workshop (Los Angeles), 1963. © Marvin Silver

Arne Glimcher had visited Nevelson while she was at Tamarind to persuade her to make good on the casual agreement she had offered in Venice. By the end of his three-day visit, Nevelson agreed to join him in his new gallery when he opened in New York, and he had immediately offered her an advance of six thousand dollars, which she duly accepted and sent a portion of to her son. Friends of Nevelson, including Mark Rothko, questioned her judgment about selecting such a young untried dealer, telling her, “Nobody knows who he is.” Her response was in character: “But I know who he is.”52

Despite the verbal and financial commitment, Glimcher and Nevelson were not yet legally free to act on the new partnership. But it was enough to ground her, and she took back her life and her future.

On November 22, 1963, Nevelson won her court battle with Janis and Kurzman. Janis was obliged to return her sculpture, and she was no longer threatened by Sam Kurzman or in any way tied to him.53 Her lawyer Harris Steinberg ended up with a beautiful white-painted Nevelson sculpture.

Decades after the event, Rufus Foshee said: “I felt then, and I feel still, that I was right in pushing Louise for a new beginning. I was right in premise, wrong in choice of lawyers. Despite the downside of the clean break, I think in the long run it gave Nevelson a new perspective.”54 But it’s not so clear that Nevelson ever forgave Rufus Foshee for encouraging her to take the steps that led to what she called “the second worst mistake” of her life—her partnership with Sidney Janis. Her marriage to Charles Nevelson had been the first.

She needed to be active to regain her standing in the art world after the Janis fiasco, and it was natural for Nevelson to turn to an organization which she respected and where she had always found respect. In the spring of 1963 she had been elected the first woman president of Artists Equity, a group she had been part of since the early 1950s. She knew she had to stay visible, and this position gave her the chance to exercise her ability to think on her feet and sound both confident and authoritative even when she wasn’t feeling that way.55

She also continued her long-standing practice of accepting most invitations to participate in art-world activities and various group shows no matter how minor. At the end of 1963 she exhibited at the East Hampton Gallery and at the Sculptors Guild annual show at Lever House in New York City. In December of that year she took part in an exhibition and auction held in Boston to benefit a group called Turn Toward Peace, which was advocating the Test Ban Treaty and an end to the Cold War. In late January 1964 she had a one-woman show at the Gimpel Hanover Gallery in Zurich.

Nevelson spoke on panels at local galleries and universities and served on juried shows for barely known galleries, efforts which allowed her to put her money where her mouth was—she would support creativity wherever and whenever she could. They simultaneously opened new doors to possible collectors and enthusiasts. In January 1964, for example, Dorothy Miller of MoMA arranged for ten to fifteen members of the museum’s Junior Council to visit her studio. These wealthy young people were being cultivated as future art buyers and donors to the museum. A few months later she participated in a panel discussion, “The New Face in Art,” at New York University’s Loeb Student Center in collaboration with Contemporary Arts Gallery and Granite Gallery. By making herself available for three hours on a Sunday afternoon she could reach the two hundred and fifty young college students in attendance (and, in fact, a much larger audience, since the discussion was later broadcast on the radio station WBAI). Furthermore, the wall she and Nelson Rockefeller had given NYU in 1960, Tropical Garden I, was on view behind the panelists. As the moderator pointed out, Nevelson’s beautiful wall would be “ ‘the silent speaker’ that will have the last word.”56

Arne Glimcher’s recollection of his early years with Nevelson are tinged with bittersweetness. She would be his star and eventually brought other artists to his firmament. But first he had to save her and persuade her that he was not too young to do the job she needed done: “Her house was empty and she wasn’t working,” Glimcher recalled. “She felt that her work had been taken away by Janis and that without it there was no future for her. For about six months she thought a lot about suicide. I think it was the major focus of her life. Both she and Teddy told me she was on the window ledge a couple of times. She was drinking like crazy. It wasn’t that she was drunk for a day—she was drunk for two weeks. It was her way of losing herself, escaping.”57

But Glimcher was determined to see her back in action. She was too talented—reminded him too much of his assertive mother—to disappear into the gutters of New York. After they had been working together profitably on all sides, for a time, she took care not to let him ever see her drunk again.

When she was at her lowest, Nevelson said that all she wanted were the three large walls she had shown in the ill-fated Janis exhibition. Glimcher arranged to get them from Janis and returned them to Nevelson’s studio. Surrounded by her own sculptures, she could pull out of the deep funk into which she had fallen and start working again.58 With borrowed money, Glimcher had paid Janis back Nevelson’s twenty-thousand-dollar advance, and he had also given her an additional seventy-five hundred to live on while she was getting back on her feet. He took none of her work to the gallery.

After the dust settled, after her return to productivity, after she had recovered her two houses on Spring Street and her three walls from Janis, after she stopped drinking too much, after she was finally moving forward with Glimcher, Nevelson took responsibility for the nightmarish period through which she had just passed. She knew she had been ambitious and overweening and that it had clouded her judgment. The infamous meeting with Kurzman, arranged by Rufus Foshee, had given her the entrée to the Sidney Janis Gallery, and she had walked on her own two feet into the lion’s den. But after her rancorous dispute with Janis and Kurzman, after her many drunken days and nights, Nevelson had to pick herself up and move forward.

As time passed, Glimcher saw himself as Nevelson’s closest friend. Had he not been nearly forty years younger and not happily married to his high-school sweetheart, who knows what would have happened between them. With his support, Nevelson expanded in new directions as an artist, and became world famous. Anything she needed, he would provide. Whether it was money, limousines, stylish clothes, a chinchilla coat, access to unconventional materials, he would make it available. While some of her early supporters never forgave Arne Glimcher for what they mistakenly saw as his encouragement to wear outlandish outfits, they must have forgotten Nevelson’s long time predilection for outrageous fashion. No one besides herself could influence Nevelson’s idea of fashion.

Glimcher called Nevelson every day. Just as Nevelson called her sister Lillian every day. They were family to each other. And for both, that meant closeness and total reliability. Their parents and siblings had stood by them through hard times, certain of future success and certain that their individual talents would eventually bring them success. Glimcher had “made it” faster and younger; it took Louise much longer. But since it had always been harder for women in the arts, as in other professions, no one in her family was surprised or reluctant to support her for more than three decades.

An absolutely crucial feature that Nevelson and Glimcher shared was a sense of space. If she had the soul of an architect, he had the gift of installation. From the beginning of his career, Glimcher developed an extraordinary talent for positioning paintings on the wall and sculpture in space so perfectly that their aesthetic strength became stunningly visible.

Before working with Glimcher, Nevelson had almost always installed her own shows, but she quickly learned to trust his judgment and stepped aside—not far away, but aside—while he put her work on display. Their absolute faith in each other’s spatial sense explains why she later chose to work closely with him in 1977 while making her first large-scale room—her magical environment—Mrs. N’s Palace. They were both quick and certain about where and how to place objects. Nevelson called it the fourth dimension; Glimcher called it good gallery practice.

Over time Glimcher and Nevelson discovered other commonalities. They had both begun life as shy, sensitive young people; both had learned the value of self-presentation. Arne Glimcher had become an elegant, confident, sometimes mercurial, often charismatic world-renowned art dealer. Louise Nevelson gradually built up the internal confidence and courage to present herself as a magical, self-assured, and glamorous presence.

It would be a combination of Glimcher’s moral and fiscal support, and the day-to-day practical support of her assistants, Teddy Haseltine and Diana MacKown, that made the last three decades of Nevelson’s life so harmonious. It was, of course, a two-way street: “It was thanks to her,” as Arne Glimcher later said, “that I was able to bring the gallery to New York. Because of her charisma and what she saw in me, it wasn’t just another gallery.”59

Glimcher was also a marketing genius, and with his canniness and creativity Nevelson’s work became increasingly important. He genuinely loved her work and was eager to share it with his friends, even in unconventional ways. Indeed, his oldest friend Dick Solomon, recalled Glimcher’s showing up at his apartment in Boston at seven-thirty one morning to deliver a gold wall, which Solomon had neither seen nor agreed to purchase. “I ran into Arne that morning. I asked what he was doing there. He said he was bringing me ‘a Nevelson.’ (That was my first encounter with the artist.) I said that’s very nice, but I have to go to work. He said, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ So when I came home that night, there was a wonderful gold Nevelson wall, which is still in my apartment in New York.”60

As Nevelson began to produce work for her first show at Pace Gallery in New York in November 1964, it was clear that she had learned from the Janis fiasco. However much Colette Roberts had understood and admired the gold- and white-painted work, Nevelson had gotten the message, and the Janis show would be last time she worked in three colors.

Contrary to the prevailing opinion, Nevelson’s lifelong reputation of refusing to respond to critics was never accurate, and when it came to Hilton Kramer she was particularly attentive. After all, by naming her the “architect of light and shadow” almost a decade earlier, he had helped her understand and articulate what she was doing. Other reviewers now mostly repeated his mantra. And, yes, do more black. Nevelson put away her gold paint and returned to her forte: black-painted wood sculpture. But however chastened by all that had gone down in 1962 and 1963, however angry, however pressured she felt by her new and uncertain financial situation—having thrown her lot in with an unknown dealer—she did not stand still. In 1964 she began to move forward with renewed energy and renewed enthusiasm for the unknown.