6

THE NEXUS OF TIME

As I grow accustomed to viewing the universe in more animate terms, there seems to be a progression in my thinking. First it was possible to grasp the notion that other beings in the animal kingdom have spirits or souls. Then my mind was opened to the very real possibility that beings in the plant kingdom have spirits. The notion that thingy things, concrete objects, both small (stones) and large (mountains), and moving things such as water or the moon could also be animate—well, that came more slowly, until the following event.

February 19, 2018

February 19, 2018

Grandfather’s Watch

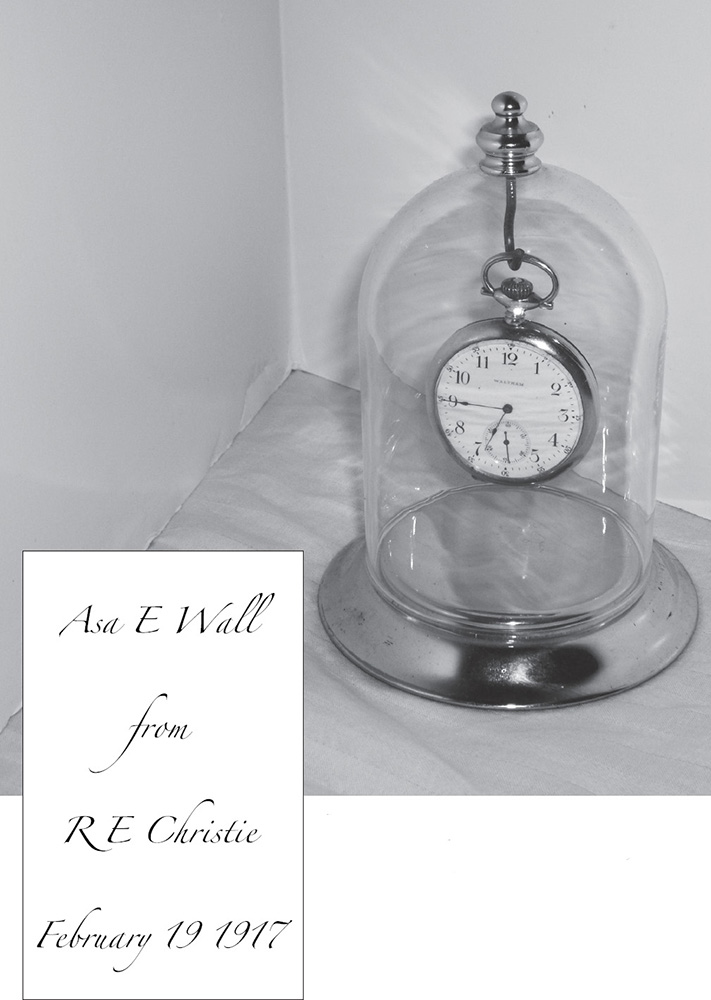

The gold pocket watch danced under its little glass dome, where it was suspended from a small hook at the top of the tiny glass vitrine. We were listening to a collection of Johnny Cash recordings titled Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian.

This occurred two days ago, when a visiting Potawatomi elder, my wife, Carolyn, and I were discussing how memories of Indian ancestors had been passed down to us and what we were doing to keep traditions alive, or even to renew them.

We had just been discussing my grandfather’s involvement in World War I and how a gold pocket watch, sitting on the windowsill nearby, had mysteriously come into his possession at that time. This inspired me to play Bitter Tears, as our visitor had not heard about the recording. The connection to our discussion was one of the songs in the collection of sad tales about Native American history: a ballad about Ira Hayes, a World War II war hero and a Native American of the Pima tribe, who was involved in the famous hill attack on Iwo Jima. The event is immortalized in a Pulitzer Prize–winning photo by Joe Rosenthal, commemorating Marines planting a U.S. flag after most of the attacking force had died taking a strategic hill near the end of the Pacific war. The campaign on Iwo Jima began on February 19; the hill was captured in a few days. Ira Hayes later died ignominiously of alcoholism and neglect.

As the music played, I reached for and opened my grandfather’s watch, and then read the engraved dedication (see below).

Robert E. Christie was a friend of our grandfather. He worked for the War Department during World War I, was a friend of James Forrestal (later the first Secretary of Defense), with whom my grandfather had some mysterious connection, and was involved in high-level inspections of troop preparedness in Europe. According to my grandfather’s diary, he reconnected with Bob Christie in Scotland on his way to the front in France in early 1918, when Christie was apparently on an inspection tour.

Grandfather Asa’s gold watch had sat, unwound and unanimated, on the windowsill in our dining nook behind our table for many months.

As the music played, I brought out a box of family Indian artifacts: pottery, wampum, and weavings, which I placed a few feet away from the watch.

I am honored to be the temporary caretaker of these family artifacts. But I am also pained. Every time I look at the watch, I think of Native Americans like Ira Hayes, fighting in two world wars, wearing the uniform of the army that not so long ago had been active in genocidal practices against our people.

Fig. 6.1. At left, the engraving on the back of Asa’s watch and, above, a photo of the watch

As the Bitter Tears collection played, and then as “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” came on, I noticed that my grandfather’s gold watch began to move. It became ever more animated by the minute. I called Carolyn. Pointing at the watch, I observed everyone’s astounded faces. Carolyn initially suggested that the watch was pulsing to the beat of the song. Johnny Cash does have a powerful voice with rich, deep tones, and Carolyn’s explanation was a reasonable interpretation of what we were seeing. However, the watch’s movements continued long after the music ended.

I compared this event to the dancing column of water in the cup by my mother’s bedside during the last hours of her life. Matt the harpist had just finished playing for my mother, who was comatose. At that time Carolyn had also suggested the strange motion was resonance with the music. However, even long after the harp music ended, we sat in silence, spellbound, staring at the glass as the water continued to dance.

When I wrote to family about this amazing event, my cousin Barb had written: “Nibiseh Manidoosag, Little Water Spirits . . . what a blessing and wonderment to have witnessed, to have been with your mom helping her on her journey home.”1

So once again we observed the energy of ancestral visitations manifested in a very material form, channeled through time, animating a timepiece, Asa’s watch.

We momentarily left the table and the pulsing watch to examine the nearby items that had once been in the trunk of my grandparents’ attic. But we could not turn our attention fully away from the dancing watch.

Among the items we were examining were handwritten notes from my grandfather’s cousin, known as Aunt Emma, to my mother and her siblings. An educator of Native Americans, she had written often to Asa’s children and had sent them objects, such as pottery and small weavings, illustrating Native American art. They were gifts that Emma’s students had given to her. In the spirit of giving, she had passed them along to her kin.

Emma was one of the Red Progressives, who formed the first Native American advocacy organization created by and for Native Americans, the Society of American Indians, at the beginning of the twentieth century. Aunt Emma had an illustrious career that included a presentation of her work at the Chicago Exposition in 1893.

When the Indian elder held Emma’s notes explaining the origins and meaning of the objects on our table, her hands trembled. She explained that she felt intimately connected to an individual whom she had previously known only by name and as a historical figure. Perhaps the spirit of this strong woman, Aunt Emma, was also present. The connection that Emma had hoped mere objects could make for our parents suddenly spoke mutely yet eloquently a generation later. It was as if we were experiencing a family gathering in our house.

Holding Emma’s gifts in our hands, we turned and looked again intensely at the watch, It was swinging agitatedly. The tribal elder approached it reverently and began to sing in Potawatomi. The watch danced and continued to dance.

It became particularly agitated when, a half hour later, our visitor prepared to return home.

Shortly after the elder’s departure, the watch ceased to pulse.

Since these events, I have moved the watch several times, thinking that perhaps its inner spring mechanism had been activated by my movement. But I could not reactivate the motion. The second hand, a delicate watch face within the watch, never moved one iota when I moved it. The watch clearly was not moving as a result of an unwound spring mechanism.

Asa’s watch is now hanging once again, immobile in its little glass house, back on the windowsill, an ever ready gateway to times and people of the not-so-distant past.

Today, two days after the events described above, is the 101st anniversary of Robert Christie’s presentation of the watch to my grandfather. It is also the seventy-third anniversary, to the very day, of Ira Hayes’ landing on Iwo Jima.

Native Americans measured time by moons, seasons, and important historical events. Did our ancestors know, in their time, from their side, of the anniversaries we calculate? Did they sense a gathering of kin at this place, around these objects, these portals of time? So it would seem. And they took this opportunity to send a message: we are present.