Stakeholder analysis and management

A stakeholder is any group or individual with an interest or a stake in the operations of a company or organisation – anyone who can affect or be affected by its activities. Stakeholder analysis is the process of identifying an organisation’s stakeholders and assessing their influence, or how they are affected, so as to manage relationships with them.

Operational stakeholder management relates to each manager within their own division undertaking the stakeholder analysis in order to clarify priority objectives and initiatives to better manage the motivation, cohesion and allegiance of key stakeholder groups. Stakeholder management is as applicable to individual projects and programmes as it is at the organisational level, so stakeholder analysis can be used in these areas as well.

In the past few decades, companies have been managed with financial returns for shareholders as the priority. Stakeholder theory, however, argues that the interests of all stakeholders – not just those with a financial stake in a business – should be taken into consideration. Stakeholder thinking suggests that this approach will contribute to the success of the business and ultimately the interests of shareholders. The needs of each party should be respected and understood, and, where practical to do so, met. It is essential that the concerns of all stakeholders are taken into account in order to maximise the value of the organisation. Managers need to identify who the key stakeholders are to effectively achieve this.

The stakeholder approach has been traced back to the work of Robert F. Stewart and Otis J. Benepe, who coined the concept when they were both at Lockheed Aircraft in the 1950s and developed it together at Stanford Research Institute in the 1960s. Growing interest in the role of business in society has also contributed to the popularity of the stakeholder approach, which focuses on not just a company’s internal processes but also the wider social context in which it operates.

The primacy of the approach of maximising shareholder returns has been criticised for business as well as social reasons. Experts on governance such as Bob Garratt, Gordon Pearson and the late Sumantra Ghoshal have pointed out that shareholders do not own the company; they own shares in the company and benefit from limited liability. It is only through an understanding of the contribution of different shareholders that we can identify the sources of profit.

The aim of stakeholder analysis is to provide decision-makers with information about the individuals and groups that may affect the achievement or otherwise of their goals. This makes it easier to anticipate problems, gain the support of the most influential stakeholders, and improve what the organisation offers to different groups and individuals and how it communicates with them.

Action checklist

1 Gather information

Involve people from across your organisation to ensure that you get a full picture of all stakeholders. Relevant information can be gathered through brainstorming sessions, interviews and literature or internet searches.

2 Identify stakeholder groups

Writers have identified various types of stakeholders. They can be internal, for example employees, managers, trade union members or departments, or external, for example customers or suppliers. A distinction can also be drawn between primary and secondary stakeholders. Primary stakeholders define the business and are crucial to its continued existence. The following are normally considered primary stakeholder groups:

- customers

- suppliers

- employees

- shareholders and/or investors

- the community.

Secondary stakeholders are those who may affect relationships with primary stakeholders. For example, an environmental pressure group may influence customers by suggesting that your products fail to meet eco-standards. The list of secondary stakeholders can be long and may include:

- business partners

- competitors

- inspectors and regulators

- consumer groups

- government – central or local government bodies

- various media

- pressure groups

- trade unions

- community groups

- landlords.

Stakeholder groups vary enormously according to the nature of the business. A public-sector contractor, for example, might list central or local government as a primary rather than a secondary stakeholder. A train or media company may list its industry regulator as a primary stakeholder.

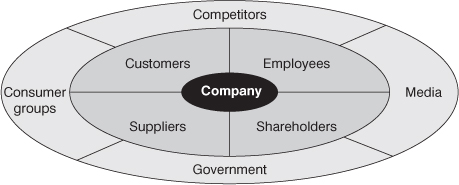

One way to map stakeholders is shown in Figure 3, with the organisation in the centre, primary stakeholders in the first circle and secondary stakeholders in the second.

4 Be specific

At this stage, it is important to think about exactly who the stakeholders are and to name specific groups and individuals. Segment the groups where necessary. For example, list specific customer segments or divide your customers into retailers, distributors and end-users.

5 Prioritise your stakeholders

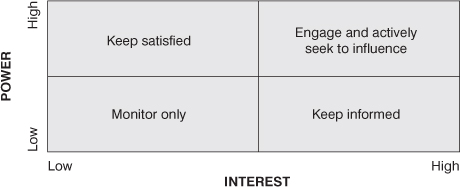

A power/interest grid can be used to map the level of interest different stakeholders have in the operations of your organisation and their power to affect or be affected by it (see Figure 4). This will help you decide where you need to invest your stakeholder management efforts. Clearly, you need to engage fully with those who have a high level of interest and a high level of power and develop good relationships with these groups. You need to keep those who have power but less interest satisfied, but not overwhelm them with information. Those with high interest and little power should be kept informed, but you do not need to pay so much attention to those with little interest and little influence.

6 Understand your stakeholders

Ask yourself what each stakeholder’s perspective of your business may be:

- What are their needs and concerns?

- What affects or influences them?

- What do they believe?

- What motivates them?

- What potential threats or opportunities do they represent?

Consider what you know about their present and previous behaviour and what underlies it. It can be helpful to draw up a table listing each stakeholder and showing the level of priority you have assigned to them, the relationship you have with them and how they are affected by your organisation.

7 Develop strategies for action

Once you have decided which stakeholders you most need to influence and have begun to understand what motivates them, you will be in a position to consider the way forward. Here are a few questions to consider:

- How can you improve the products and services you offer to customers?

- Do you need to tailor your offering to different customer segments?

- How can you cooperate more effectively with suppliers?

- What will enhance the morale of your employees?

- What internal issues need to be resolved?

- What might encourage external stakeholders to be more cooperative?

- How can you change public perceptions of your organisation?

- Which policies or actions might run the risk of alienating them or increasing the threat they pose to your business?

- Which areas should you focus on?

Evaluate the impact of any proposals, considering how easy they will be to implement, taking any costs or cost savings into account and bearing in mind the impact on other stakeholders. Edward Freeman, Jeffrey Harrison and Andrew Wicks, authors of Managing for Stakeholders, suggest that trading off the interests of one group of stakeholders against those of another is a risky strategy. It may be more effective, although not easy, to find creative solutions that satisfy the interests of multiple stakeholder groups.

8 Communicate and develop relationships with stakeholders

A ‘public relations’ approach to stakeholders, i.e. one-way communication, can be used to put the company viewpoint across, but it will be effective only if the assumptions on which it is based are accurate. Two-way communication, involving dialogue and negotiation with stakeholders, may be more difficult, but it can lead to a better understanding of stakeholder perspectives. It can also foster your credibility with stakeholders and contribute to the development of relationships based on trust and respect, the resolution of conflicts and the evolution of win-win scenarios. Monitor the feedback you get from stakeholders and use it as a basis for further discussion and action. Stakeholder management is a two-step process, the second step being to develop a proactive communication plan aimed at supporting business strategy and seeking to move stakeholders towards supportive positions and away from positions that threaten business success. Moving stakeholders progressively in the right direction on the power/interest matrix should be the aim.

9 Monitor and review

The environment within which a company operates is not static. The power and interests of stakeholder groups will change, so a regular review of stakeholder relationships is essential.

As a manager you should avoid:

- assuming that you know what your stakeholders are thinking

- trading off the interests of one group against those of another

- ignoring the concerns of stakeholder groups that are critical of the organisation

- neglecting the interests of important stakeholders.

Gathering competitive intelligence

Competitive intelligence (CI) provides organisations with actionable information regarding competitors’ plans, activities and performance and is a crucial part of an overall analysis of the operating environment. The information gathered (which can cover everything from new products, pricing structures and new recruits to overall strategic direction) is used to make both short-term and long-term plans in a number of areas, such as strategy, mergers and acquisitions, pricing, marketing, advertising, and research and development.

CI is both a product and a process:

- The product is information that can be used as the basis for a specific action (e.g. acquiring another company).

- The process is the systematic acquisition, analysis, evaluation and dissemination of information about known and potential competitors.

The effective gathering, analysis and application of CI can be a valuable tool, providing insights into the behaviour of current and prospective competitors and an understanding of the wider competitive environment. CI can support strategic decision-making, inform organisational positioning, build market orientation and help businesses to achieve competitive advantage.

In a complex and intensely competitive environment, where consumers are increasingly sophisticated and well-informed, it is not enough to collect information about the activities of competitors on an informal or ad hoc basis. Although conversations with clients and industry contacts and information from the media can be useful sources of intelligence, it is also important to take a more proactive, thorough and structured approach to CI. This can help organisations to minimise surprises, exploit opportunities and manage threats. Plans can be formulated on the basis of hard information and the organisation can learn from its competitors.

There are ethical and unethical approaches to gathering CI. Publicly available information from sources such as press releases, annual reports, job advertisements and the internet poses few ethical questions. However, sending employees to job interviews at competitor organisations is questionable. Business espionage using methods such as electronic surveillance and hacking is highly unethical and in most cases illegal.

This checklist provides guidance for individuals or organisations wishing to take a structured and proactive approach to gathering CI as part of a wider programme of market and environmental analysis.

Action checklist

1 Integrate CI into a single system

CI should be integrated into a central organisational system for the storage and retrieval of information. Make sure that information gathered by different departments and functions is fed into a single market and competitor database so that it is available to those responsible for strategic analysis and decision-making. In an integrated system, comprehensive reports can be produced and data can be optimally used for strategic purposes as well as at the operational level.

This may be achieved through an organisational market information and knowledge management system or a wider management information system (MIS) encompassing information derived from:

- the internal accounting system – especially sales analysis

- market intelligence – information from external sources, including the media and industry reports

- market research of all kinds – this may include information on indirect competitors or alternative products that may affect your customers’ choices. This research can be either generated internally or commissioned externally from specific research organisations or industry bodies.

The intelligence gathered as the basis of marketing research is usually referred to as data and can be classified as:

- primary data – information collected by means of a specific research programme

- secondary data – information that already exists, because it was collected as part of a previous research project or for some other purpose. Identifying relevant sources of secondary information, extracting the relevant data and analysing it are usually referred to as desk research. Some companies set up a dedicated team to collect and circulate CI or subcontract the work to specialist companies.

2 Gain commitment from top management and across the organisation

Formal responsibility for CI may be assigned to a specific department or individuals, but input will be needed from individuals and teams across the organisation if the gathering and analysis of data are to be carried out comprehensively and effectively.

Commitment from senior management is required to make sure that resources are made available, particularly as direct returns on investment may be intangible in the short term. Staff time to cover the effort (and costs) of collecting, storing, analysing and constantly updating the information is the major resource involved, and these costs need to be monitored and controlled. Costs will also be incurred for activities such as travel to conferences and exhibitions, searching online databases and subscribing to journals. Senior management commitment is also important in ensuring that CI is taken seriously and acted on. The benefits will not be realised if CI remains an exercise in data collection and information is not analysed and applied.

3 Define the objectives

The gathering of CI needs to be conducted in a planned and thorough manner. Some kind of logical sequence should always be followed. It is vital to be clear from the outset why the research is required.

Usually CI is required to help senior managers and heads of department with management decision-making. Whoever is responsible for carrying out the research must engage with these decision-makers to make sure that the relevant CI is gathered and that it is presented in the most appropriate way. This will ensure that the resources available are used wisely, not wasted on exploring the wrong market, the wrong competitor or the wrong strategy, thus generating poor, irrelevant or misleading CI.

A wide range of issues may need to be addressed, for example:

- attempting to find weaknesses within another organisation

- finding out what the competition is in a new market that the organisation is hoping to enter

- investigating a particular organisation that is seen to pose a threat.

CI programmes should also include the provision of information for strategic decisions and early warnings of competitor activity. This kind of research would be wider and more generic.

Managers may wish to:

- focus in on their market and identify who or what constitutes competition for the organisation

- identify which of the many market forces is most important so they know where to focus their time and efforts

- understand which strategies their competitors are pursuing.

You must clarify what type of data and information the CI programme will collect. Examples may include competitor pricing, competitor recruitment drives, competitor marketing communications – such as new advertising campaigns – and competitor strategy.

In summary, clear and specific objectives for the CI programme will provide a focus and help reduce the amount of information that needs to be collected. The objectives should not be set in stone and must be reviewed regularly.

4 Develop the research plan

For example:

- Define the organisations from which information will be gathered. This could include competitors, peers, customers and industry bodies as well as suppliers.

- Decide on the survey methods to be used.

- Plan the approach in detail, working out a timetable and allocating human and other resources.

- Assemble the team and assign responsibilities. The number of people involved in the CI programme will depend on the objectives that have been set. One individual must be given overall responsibility for the CI programme; he or she must be a good communicator with strong information and project management skills, including the ability to work to deadlines.

5 Identify information sources

Some experts in the field of CI believe that most organisations already hold, or have access to, 80% of the information required to assess their competitors. Significant secondary data can be found within a company through its people and their current knowledge.

Additionally, many external sources of secondary data are available, in government departments, trade associations, professional bodies, the press, specialist research agencies, academia and so on. Some research agencies operate syndicated research programmes that are set up on a cooperative basis and paid for by contributions from each of the companies taking part. It is possible to subscribe to such programmes. Alternatively, agencies sometimes commission research programmes and offer the results for sale. Trade associations often make information freely available to their members but sell it to ‘outsiders’.

The techniques used to collect CI fall into four main groups:

- Reviewing published materials and public documents – annual reports, press releases, online databases and internet sites, the media, advertisements (especially competitors’ recruitment advertising defining the kind of people they are looking for), product catalogues, other promotional brochures, and patents and trademarks.

- Observing competitors or analysing products – attending exhibitions and conferences, and buying their products and dismantling them as part of a benchmarking exercise.

- Making contact with people who do business with competitors – personal contacts in other trade organisations and existing customers.

- Talking to recruits and competitors’ employees – job interviews with candidates working with competitors, conversations with competitors’ staff at industry functions and networking events, direct contact with competitor organisations and making specific enquiries.

Do not overlook the importance of frontline staff as sources of CI. They are likely to pick up competitor information through dealing with customers. Make them aware of the need to keep a lookout for information and put in place procedures to gather the information.

Remember that all this information should be put into an integrated marketing information system that is constantly being updated.

6 Develop an international perspective

Remember that language and cultural differences may limit cross-border intelligence gathering. It is not easy to approach competitors’ employees, and people are particularly wary if approached by someone from a different country. Moreover, bear in mind that activities that are acceptable in one country might be illegal in another.

The cardinal rule of international corporate intelligence is that the best international competitor intelligence resource is your own organisation.

Most CI is probably available within your organisation. Even if it does not have offices overseas, you may have contacts worldwide through trade representatives, affiliates and suppliers. You need to appreciate that your organisation – particularly if it is globally based – possesses all three informational dimensions: competitor-specific; product- or technology-specific; and region-or country-specific. Be careful to take all three dimensions into account, not just two. For example, a sales person may know a great deal about a particular competitor or a specific technology but will also possess region or country knowledge.

7 Make the best use of technology

Technology can be used in two ways:

- Gathering research. Online databases and the internet are useful intelligence tools because they provide ‘instant research’. However, they have limitations. The information may be out of date, inaccurate, biased and/or incomplete, so this kind of research must be undertaken with caution. The source of the information should be validated wherever possible so that its reliability and authority can be assessed. The currency and accuracy of the information should also be checked.

- Storing research and intelligence. Using a database to store the information you collect will allow you to search for a subject or a competitor more easily. Be aware of copyright legislation – it is illegal to scan many documents, such as press clippings, into an electronic format, but you may keep references or the newspaper in hard copy.

8 Consider primary data sources

If information required for a particular CI research project does not exist as secondary data, you have to determine the best way of collecting primary data. There are three fundamental approaches:

- Observation. It is sometimes more informative to watch what people do rather than talk to them. This eliminates interviewer bias and pre-empts the problem of people not always remembering their actions clearly, especially trivial ones.

- Experiment. Simulating a real situation is often a better way of assessing likely future behaviour than asking people hypothetical questions. For example, if you want to know which of two possible packages shoppers would prefer, you can put them side by side in a real or dummy shop and see which one is chosen. Test marketing is an example of experimenting in order to obtain CI data, although it has the drawback of potentially alerting your competitors to what you are doing.

- Survey. This is normally associated with competitor market research. It normally involves asking a predetermined set of questions to gather information. These questions can have either fixed or free-form responses. It is important to make sure that the survey covers all the areas required.

9 Analyse the information

The concept of analysis can be intimidating and it is not uncommon for organisations to gather information but fail to analyse its implications for their business. The analysis and interpretation of the data are crucial for the production of effective competitive intelligence. The management guru Peter Drucker has said that ‘information is the manager’s main capital’. For this capital to produce healthy returns it must be converted into intelligence, and analysis is the means of doing so.

The analysis should attempt to fulfil the objectives defined in point 3 above. However, it is important to be aware of potential problems when analysing the data:

- The data may be incomplete. Despite a thorough data collection process, there may be gaps in the data. There are two ways to address this issue – either further research is commissioned, or, if this is not possible, these gaps need to be highlighted and any assumptions used to fill them clearly explained.

- The data may contain contradictions. Again there are two options – further research is commissioned or these contradictions are highlighted in the analysis.

- The sample size was not large enough. If you are trying to gather competitor analysis, it may not be possible to collect data on all your competitors. This could skew the analysis, so any issues with sample size should be documented.

10 Compile a report

The report should clearly meet the objectives defined in point 3 above. It should also clearly state any problems or gaps in the data and the assumptions made during the analysis.

Brevity is important when reporting the information gained from the CI programme. Keep the intended audience in mind; highlight the most important points and provide references to further information.

Decide how often a report should be produced (weekly, monthly or even annually may suffice in some organisations whereas others may require daily reports). Frequency is based on the speed of change in the market in which you are operating.

11 Consider competitor responses

When considering actions as a result of the findings of CI, think about how your competitors will respond. There are four possibilities:

- No response. Are they weak or a sleeping giant? What if they wake up?

- Fast response. Some competitors may respond quickly and with such impact as to nullify your actions. What will you do if they do this?

- Focused response. It is possible that the competition will only change one variable (usually price). What will you do then?

- Unpredictable response. This is the most difficult to deal with, so what are your contingencies?

12 Take action on the results

CI gives a strategic advantage only when it is analysed and acted upon. Keep records of occasions when information was used successfully to gain advantage over competitors and also when it was too late to take action. This will help you improve the data collection and analysis process.

Do not jump to counteract a competitor’s movements without considering your organisation’s objectives. Only the right action for you, at the right time, will bring competitive advantage.

13 Learn and make changes

Monitor and evaluate the CI programme regularly and consider areas for improvement. Take action on any recommendations and keep communicating CI successes.

As a manager you should avoid:

- spending time and money gathering information that is no longer relevant to the organisation

- collecting data without analysing it

- overstepping the ethical line – check your organisation’s code of conduct

- failing to communicate the success of the CI programme

- imagining that imitating competitors or beating them fractionally to market is the key to organisational success – seeking greater differentiation from the competition is a more effective route to a market advantage

- forgetting that competitors may also be trying to gain intelligence on your organisation.

Michael Porter

What is strategy?

Introduction

In an age when management gurus are both lauded by the faithful and hounded by the critics, Michael Porter (b. 1947) seems to be one of the few who are well-accepted both academically and in the business world. Though he has his critics, Porter has generally been viewed as being at the leading edge of strategic thinking since his first major publication, Competitive Strategy (1980), which became a corporate bible for many in the early 1980s.

Life and career

Porter completed a degree in aeronautical engineering at Princeton in 1969 and took an economics doctorate at Harvard, joining the faculty there as a tenured professor at the age of 26. He has acted as a consultant to companies and governments and, like many academics, has set up a consulting company, Monitor.

Key theories

Porter’s thinking on strategy has been supported by research into industries and companies, and has remained consistent as well as developmental. He has concentrated on different aspects at different times, spinning the threads together with a logic that is irrefutable.

Before Competitive Strategy, most strategic thinking focused either on the organisation of a company’s internal resources and their adaptation to meet particular circumstances in the marketplace, or on increasing an organisation’s competitiveness by lowering prices to increase market share. These approaches, derived from the work of Igor Ansoff, were bundled into systems or processes that provided strategy with its place in the organisation.

In Competitive Strategy, Porter managed to reconcile these approaches, providing management with a fresh way of looking at strategy – from the point of view of industry itself rather than just that of markets, or of organisational capabilities.

Internal capability for competitiveness: the value chain

Porter describes two different types of business activity: primary and secondary. Primary activities are principally concerned with transforming inputs (raw materials) into outputs (products), and with delivery and after-sales support. These usual line management activities include:

- inbound logistics – materials handling, warehousing

- operations – turning raw materials into finished products

- outbound logistics – order processing and distribution

- marketing and sales – communication and pricing

- service – installation and after-sales service.

Secondary activities support the primary and include:

- procurement – purchasing and supply

- technology development – know-how, procedures and skills

- human resource management – recruitment, promotion, appraisal, reward and development

- firm infrastructure – general and quality management, finance and planning.

To be able to survive competition and supply what customers want to buy, a firm has to ensure that all these value-chain activities link together and fit, as a weakness in any one of them will affect the chain as a whole as well as competitiveness.

The five forces

Porter argued that to examine its competitive capability in the marketplace, an organisation must choose between three generic strategies:

- cost leadership – becoming the lowest-cost producer in the market

- differentiation – offering something different, extra or special

- focus – achieving dominance in a niche market.

The question is to choose the right one at the right time. These generic strategies are driven by five competitive forces, which the organisation has to take into account:

- the power of customers to affect pricing and reduce margins

- the power of suppliers to influence the organisation’s pricing

- the threat of similar products to limit market freedom and reduce prices and thus profits

- the level of existing competition which affects investment in marketing and research and thus erodes profits

- the threat of new market entrants to intensify competition and further affect pricing and profitability.

In recent years, Porter has revisited his earlier work and emphasises the acceleration of market change, which means companies now have to compete not just on a choice of strategic front but on all fronts at once. Porter has also said that a company that tries to position itself in relation to the five competitive forces misunderstands his approach, since positioning is not enough. What companies have to do is ask how the five forces can help to rewrite industry rules in their favour.

Instead of going it alone, an organisation can spread risk and attain growth by diversification and acquisition. Blue-chip consulting companies such as Boston Consulting Group (market growth/market share matrix) and McKinsey (7-S framework) have developed analytical models for discovering which companies will rise and fall, but Porter prefers three critical tests for success:

- The attractiveness test. Industries chosen for diversification must be structurally attractive. An attractive industry will yield a high return on investment but entry barriers will be high, customers and suppliers will have only moderate bargaining power and there will be only a few substitute products. An unattractive industry will be swamped by a range of alternative products, high rivalry and high fixed costs.

- The cost-of-entry test. If the cost of entry is so high that it prejudices the potential return on investment, profitability is eroded before the game has started.

- The better-off test. How will the acquisition provide advantage to either the acquirer or the acquired? One must offer significant advantage to the other.

Porter devised seven steps to tackle these questions:

- As competition takes place at the business unit level, identify the interrelationships among the existing business units.

- Identify the core business which is to be the foundation of the strategy. Core businesses are those in attractive industries and where competitive advantage can be sustained.

- Create horizontal organisational mechanisms to facilitate interrelationships among core businesses.

- Pursue diversification opportunities that allow shared activities and pass all three critical tests.

- Pursue diversification through transfer of skills if opportunities for sharing activities are limited or exhausted.

- Pursue a strategy of restructuring if this fits the skills of management or if no good opportunities exist for forging corporate partnerships.

- Pay dividends so that shareholders can become portfolio managers.

National competitiveness

Why do some companies achieve consistent capability in innovation, seeking an ever more sophisticated source of competitive advantage? For Porter the answer lies in four attributes that affect industries:

- Factor conditions – the nation’s skills and infrastructure to enable a competitive position

- Demand conditions – the nature of home-market demand

- Related and supporting industries – presence or absence of supplier/feeder industries

- Firm strategy, structure and rivalry – the national conditions under which companies are created, grow, organise and manage.

These are the chief determinants that create the environment in which firms flourish and compete. They constitute a self-reinforcing system, and Porter represents them as the four points of a diamond, where the effect of one point is contingent on the state of the others. Advantages in one determinant can create or upgrade advantages in others. Similarly, weaknesses at one point will have an adverse impact on an industry’s capability to compete.

The new strategic wave

Somewhere between 1980 and 1990 strategic planning came unstuck. Old theories no longer worked as customers became more demanding and changeable, and markets and technologies rose and fell ever more rapidly. Even industries that were once distinct with definable products and services now converged and became blurred. A new wave of more subversive strategic thinking – Gary Hamel in Strategy as Revolution and Henry Mintzberg in The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning – emerged to replace the old rulebook. Porter’s main contribution to date, What is Strategy?, argues that strategic planning lost its way because managers failed to distinguish between strategic and operational effectiveness and confused the two. The old strategic model – which still held up in the 1980s – was based on productivity, increasing market share and lowering costs. Hence total quality management, benchmarking, outsourcing and re-engineering were all at the forefront of change in the 1980s as the key drivers of operational improvements. But continuing incremental improvements to the way things are done tend, over time, to bring different players up to the same level, not differentiate them. To achieve differentiation means that:

- a company’s strategy must rest on unique activities based on customer needs, customer accessibility or the variety of its products or services

- a company’s activities must fit and link together – in terms of the value chain, one link is prone to imitation, but with a chain imitation is difficult

- a company must make trade-offs. Excelling at some things means making a conscious decision not to do others – being a ‘master of one trade’ to stand out from the crowd as opposed to being a ‘jack of all trades’ and lost in the crowd. Trade-offs purposefully limit what a company offers. The essence of strategy lies in what not to do.

The internet

In 2001 Porter addressed the assertion that the internet rendered strategy obsolete. While admitting that the internet was in its infancy, he observed that relying solely on internet technologies to gain market penetration was already proving not to be a sound approach. In a Harvard Business Review article in March 2001, Porter said:

In our quest to see how the internet is different, we have failed to see how the internet is the same.

He argued that many internet companies were competing through unsustainable, artificial means, usually propped up by short-term capital investment. He also argued that while the excitement of the internet appeared to throw up new rules of competition, the first wave of excitement was now clearly over, and the old rules and strategic principles appeared to be re-establishing themselves. He gave examples, such as:

- The right goal – a healthy long-term return on investment.

- Value – a company must offer a set of benefits that set it apart from the competition.

- A company’s value chain has to do things differently or do different things from rivals to reflect, produce and deliver that value.

- Trade-offs – make conscious deliberate sacrifices in some areas in order to excel, or even be unique, in others.

- All the different components in the value chain must fit together, reinforcing each other to create uniqueness and value. This is what makes a core competence – something that is difficult to imitate.

- Continuity – not only from a customer perspective but also in order to build and develop skills that provide a competitive edge.

Porter foresaw that as most businesses embraced the internet, it would become nullified as a source of advantage, while traditional strengths such as uniqueness, design and service relationships would re-emerge. For Porter the next phase of internet evolution would be more holistic, with a shift from e-business to business, from e-learning to learning, within which the internet would be a communications medium and not necessarily a source of advantage.

It is a mark of Porter’s achievement that much of his work on competitive strategy, researched in the 1970s, still has high value and relevance in the 21st century, and still shapes mainstream thinking on competition and strategy.

Although now much quoted, the following was intended to be as much a of a compliment as The Economist (‘Professor Porter PhD’, 8 October 1994) could muster:

His work is academic to a fault… Mr Porter is about as likely to produce a blockbuster full of anecdotes and boosterish catch-phrases as he is to deliver a lecture dressed in bra and stockings.

While his work is academically rigorous, his ability to abstract his thinking into digestible chunks for the business world has given him wide appeal in both the academic and business worlds. It is now standard practice for organisations to think and talk about value chains, and the five forces have entered the curriculum of every management programme. Porter’s later thinking on strategy rides the new wave of revolutionary strategic thinking led by Hamel and links consistently with his earlier work. One suspects not only that there is more to come from Porter, but also that it will be wholly consistent with what he has said in the past.

SWOT analysis is a diagnostic tool for strategic planning which involves the identification and evaluation of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This framework facilitates the assessment of internal capabilities and resources that are under the control of the organisation and of external factors that are not under organisational control. SWOT analysis involves the collection of information, rather than the framing of recommendations, which can only be considered once the facts have been confirmed. The analysis may be carried out by a single manager, but it usually involves the participation of a wider group, so that insights can be gained from across the organisation or department.

SWOT analysis emerged in the 1960s from research at Stanford Research Institute into the failure of current corporate planning methods. The technique evolved, became widely used during the 1980s and remains popular, although critics have pointed out weaknesses in its application, including a lack of analytical depth. It provides a simple framework for analysing the market position of an organisation and can be applied in a range of planning and strategic contexts including strategy development, marketing planning, and the evaluation of strategic options for a whole business or an individual department. It may be used in conjunction with tools such as PEST (political, economic, social, technological) analysis, or one of its variants, or five forces analysis, which can provide a deeper understanding of the external environment and help to assess potential risks and threats to the profitability and survival of the organisation. SWOT analysis is also used by individuals to assess personal career prospects, but this checklist focuses on its use by organisations and departments and does not cover the individual aspect.

Action checklist

1 Establish the objectives

The first step in any management project is to be clear about what you are doing and why. The purpose of conducting a SWOT analysis may be wide or narrow, general or specific – anything from getting staff to think about and understand the business better, to rethinking a strategy or the overall direction of the business. SWOT analysis usually focuses on the present situation. In the context of scenario planning, however, it could be used to look into the future and, using appreciative inquiry methods, to assess what factors have made the organisation successful in the past.

2 Select appropriate contributors

This is important if the final recommendations are to result from consultation and discussion, not just personal views, however expert. If you are conducting an organisation-wide analysis, it is important to include people from different departments to make sure that information is gathered from across the business:

- Pick a mix of specialist and ‘ideas’ people with the ability and enthusiasm to contribute.

- Consider including a mix of staff from different grades, if appropriate.

- Think about numbers. Six to ten people may be enough, especially in a SWOT workshop. Up to twenty-five or thirty can be useful if one of the aims is to help staff see the need for change, but it will be necessary to split into smaller groups for the more active parts of the process.

3 Allocate research and information-gathering tasks

Background preparation is vital if the subsequent analysis is to be accurate, and should be divided among the SWOT participants. Preparation can be carried out in two stages: exploratory, followed by data collection; and detailed, followed by a focused analysis.

- Gathering information on strengths and weaknesses should focus on the internal factors of skills, resources and assets, or the lack of them.

- Gathering information on opportunities and threats should focus on the external factors over which you have little or no control, such as social, market or economic trends.

However, you will need to be aware of and take account of the interrelationships between internal and external factors.

4 Create a workshop environment

If the compilation and recording of SWOT lists takes place in meetings, make sure that you exploit the benefits of workshop sessions. Foster an atmosphere conducive to the free flow of information and encourage participants to say what they feel is appropriate, without fearing or attributing blame. The leader or facilitator has a key role and should allow time for thought, but not so much as to let the discussion stagnate. Half an hour is often enough to spend on strengths, for example, before moving on. It is important to be specific, evaluative and analytical at the stage of compiling and recording the SWOT lists – mere description is not enough.

5 List strengths

It is often harder to identify strengths than weaknesses. Questions such as the following can be helpful:

- What do we do better than anyone else?

- What advantages do we have?

- What unique resources do we have?

- What do others see as our strong points?

Strengths may relate to the organisation – its market share, reputation and people, including the skills and knowledge of staff – as well as reasons for past successes. Try to be as specific as possible when collecting facts. For example, it is not sufficient to say that the level of profit is good. If the profit margin is 10% but the industry average is 30%, for example, there is clearly room for improvement.

Other people strengths include:

- friendly, cooperative and supportive staff

- a staff development and training scheme

- appropriate levels of involvement through delegation and trust.

Organisational strengths may include:

- customer loyalty, for example 90% repeat customers

- capital investment and a strong balance sheet, with a higher profit margin than other organisations in the sector

- effective cash management resulting in, say, 25 days’ accounts receivable as opposed to a norm of 36 days in the same industry

- efficient procedures and systems showing, for example, a 3% reduction in expenses over the past five years

- well-developed corporate social responsibility policies.

6 List weaknesses

This session should not be seen as an opportunity to criticise the organisation but as an honest appraisal of the way things are. Be careful not to take weaknesses at face value, but to identify the underlying causes.

Key questions include:

- What is hindering progress?

- What needs improving?

- Where are complaints coming from?

- Are there any weak links in the chain?

The list might include:

- customers looking for more products or services

- declining sales of the main or most popular products or services

- poor competitiveness, as demonstrated by figures showing the percentage of market share lost over the past three years and higher price increases compared with those of competitors

- non-compliance with, or ignorance of, appropriate legislation

- financial or cash flow problems

- employees not aware of the organisation’s mission, objectives and policies

- high levels of staff absence compared with average levels in the sector or rising levels of absence

- no processes in place for monitoring success or failure.

It is not unusual for ‘people problems’ – poor communication, inadequate leadership, lack of motivation, too little delegation, absence of trust – to feature among the major weaknesses.

7 List opportunities

This step is designed to assess the socio-economic, political, environmental and demographic factors that affect organisational performance. The aim is to identify circumstances that the organisation can exploit and to evaluate their possible benefits.

Examples include:

- technological developments

- new markets

- change of government

- changes in interest rates

- demographic trends

- strengths and weaknesses of competitors.

Bear in mind that opportunities may be time-limited and consider how the organisation may make the most of them.

8 List threats

Threats are the opposite of opportunities. All the factors listed above may, with a shift of emphasis or perception, also have an adverse impact.

The questions to ask include:

- What are our competitors doing?

- What changes are there in the market for our products?

- What resource problems do we have?

- What is the impact of the economy on our bottom line?

Threats may include:

- unemployment levels

- skills shortages

- environmental legislation

- new technologies that will make our products or services obsolete.

It is important to look at a worst-case scenario. However, this should not be allowed to foster pessimism; it is rather a question of assessing risks and considering how potential problems may be limited or eliminated. Most external factors are challenges, and whether staff perceive them as opportunities or threats is often a valuable indicator of morale.

9 Evaluate listed ideas against objectives

With the lists compiled, sort and group facts and ideas in relation to your objectives. Consider which of the factors listed are of major importance and which are negligible. It may be necessary for the SWOT participants to select their five most important items from the list to gain a broad perspective. The key to this process is clarity of objectives, as evaluation and elimination will be necessary to separate the wheat from the chaff. Although some aspects may require further investigation or research, a clear picture should start to emerge at this stage.

10 Carry your findings forward

Once the SWOT analysis is complete, you need to address the question of how the potential of strengths and opportunities can be maximised and how the risks implicit in weaknesses and threats can be minimised. Bear in mind that much of the information you have collected will represent symptoms rather than root causes, so further consideration of the underlying issues may be needed. However good or bad the results of the analysis are, make sure that they are integrated into subsequent planning and strategy development. Revisit the findings at suitable intervals to check that they are still valid.

As a manager you should avoid:

- giving undue weight to opinions which are not based on hard evidence

- ignoring the ideas of participants at lower levels in the organisational hierarchy

- succumbing to ‘paralysis by analysis’

- allowing the process to become an exercise in blame laying or a vehicle for criticism and recrimination

- seeing SWOT analysis as an end in itself and failing to integrate the results into subsequent planning.

PEST analysis is a technique used to identify, assess and evaluate external factors affecting the performance of an organisation with the aim of gathering information to guide strategic decision-making.

PEST analysis is a useful tool for understanding the wider environment in which an organisation operates. It involves reviewing factors which will have an impact on the organisation’s business and the level of success it will be able to achieve and may be carried out as part of an ongoing process of environmental scanning, to inform overall strategy development, or to support the development of a new product or service. Undertaking a PEST analysis can raise awareness of threats to profitability and help to anticipate future difficulties, so that action to avoid or minimise their effects can be taken. It can also alert the organisation to promising business opportunities for the future. The process of carrying out the analysis will also help to develop the ability to think strategically.

Traditionally, PEST analysis has focused on political, economic, sociological and technological factors, but increasing awareness of the importance of legal, environmental and cultural factors has led to the evolution of a growing number of variants. For example:

- PESTLE – political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental

- SPECTACLES – social, political, economic, cultural, technological, aesthetic, customers, legal, environmental, sectoral

- PEST-C – where C stands for cultural

- SLEEPT-C – sociological, legal, economic, environmental, political, technological and cultural.

This checklist focuses on the traditional four-factor analysis, but it is important for managers and business leaders to consider which additional factors are particularly relevant to their organisation and to include these in the analysis.

Framework for the analysis

To facilitate the analysis, it can be helpful to create a matrix of the factors to be analysed and the opportunities or threats they represent, as in the table below. This provides a simple framework for the analysis, but bear in mind that there will be varying degrees of overlap and interrelation between the different factors.

Political factors

This part of the analysis is concerned with how the policies and actions of government affect the conduct of business. Legislation may restrict or protect commercial operations in a number of ways. Issues to be considered under this heading include:

- the level of political stability

- the legislative and regulatory framework for business, employment and trade

- the tax regime and fiscal policy

- programmes of forthcoming legislation

- the dominant political ideology.

- When is the next election due?

- How likely is a change of government?

- Is the government inclined towards interventionist or laissez-faire policies?

- What is the government’s approach to issues such as tax, competition, corporate social responsibility and environmental issues?

- How do sector rules and regulations affect your business?

Economic factors

This part of the analysis is concerned with overall prospects for the economy. Key measures include:

- GDP/GNP

- inflation

- interest rates

- exchange rates

- unemployment figures

- wage and price controls

- fiscal and monetary policy.

Issues such as the availability of raw materials and energy resources, the condition of infrastructure and distribution networks, and the changing nature of global competition may also be relevant.

Questions to ask:

- Is the economy in a period of growth, stagnation or recession?

- How stable is the currency?

- Are changes in disposable income to be expected?

- How easily is credit available?

These are probably the most difficult factors to quantify and predict, as personal attitudes, values and beliefs are involved. Demographic factors such as birth rates, population growth, regional population shifts, life expectancy or a change in the age distribution of the population should be taken into account. Factors to be considered include:

- levels of education

- employment patterns

- career expectations

- family relationships

- lifestyle preferences

- trends in fashion and taste

- spending patterns

- mobility

- religious beliefs

- consumer activism.

Questions to ask:

- How much leisure time is available to customers?

- How is wealth distributed throughout the population?

- How important are environmental issues?

- What moral or ethical concerns are reflected in the media?

- What might be the impact of an unknown retirement age?

Technological factors

Rapid technological change has had far-reaching effects on business in past decades. Factors to be considered here include:

- investment in research and development

- new technologies and inventions

- internet and e-commerce developments

- developments in production technology

- rates of obsolescence.

Questions to ask:

- Which new technological developments will have implications for my business?

- Where are research and development efforts focused and is there a match with our own focus?

- How are communication and distribution operations being affected by new technologies?

Action checklist

1 Identify the most important issues

The usefulness of the analysis will depend not so much on the quantity of information collected but on its relevance. Consider which factors are most likely to have an impact on the performance of the organisation, taking into account the business it is in and the fields where it is active or may be active in the future. Local and national factors will usually be most important for small businesses, but larger companies will need to consider the environment in any countries in which they do business, as well as the global scene and emergent competition. Information on current and potential changes in the environment should be included.

2 Decide how the information is to be collected and by whom

Check first how much of the required information has already been collected or is available within the organisation in reports, memos and planning documents. In a large organisation, it may be wise to consult those with expertise in specific areas and delegate to them the collection of some types of information.

3 Identify appropriate sources of information

Hard factual information, such as employment figures, inflation and interest rates, and demographics, is often easily available from official statistical sources and reference books. A wide range of additional sources, such as newspapers, magazines, trade journals, research reports, websites, discussion boards, email newsletters and social networking sites, will be needed for softer information such as consumer attitudes and public perceptions. You may also wish to ask consultants, researchers and known experts in the relevant fields to supplement published material.

4 Gather the information

Decide in advance how the information is to be organised and stored, and ensure that the required computer systems for storage and analysis are in place. Take into consideration factors such as the resources available and the personnel who will need to access the information.

5 Analyse the findings

Assess the rate of change in each area: which changes are of minor or major importance, and which are likely to have positive or negative implications. It is possible that some trends will have both positive and negative effects and it will be necessary to weigh these against each other. Avoid overemphasising events with a negative effect and try to identify positive opportunities that may open up. Although a PEST analysis often focuses on anticipating changes in the environment, it is also important to consider areas where little or no change is expected.

6 Identify strategic options

Consider which strategies have the best chances of success and what actions could or should be taken to minimise threats and maximise opportunities.

Summarise your findings, setting out the threats and opportunities identified and the policy choices that should be considered. Use appendices to include relevant information. Preliminary recommendations for action should also be included.

8 Disseminate your findings

The results of a PEST analysis will be useful to those in the organisation who are responsible for decision-making and strategy formulation.

9 Decide which trends should continue to be monitored

Trends and patterns will emerge from the research and it may be clear that an ongoing review of developments in these areas will be needed. Alternatively, further evidence may be required to support hunches or hypotheses that have been formed during the analysis. Risks will need specific attention and monitoring.

As a manager you should avoid:

- making assumptions about the future based solely on the past or the present – PEST is a diagnostic tool and many other factors should be included before reaching a conclusion

- getting bogged down in collecting vast amounts of detailed information without analysing your findings

- seeing PEST analysis as a one-off – it should form part of an ongoing process for monitoring changes in the business environment

- using PEST analysis in isolation – combine it with other techniques, such as SWOT analysis, Porter’s five forces, competitor analysis or scenario planning.

Market analysis: researching new markets

Market analysis is comprehensive marketing research that yields information about the marketplace, including competitors, market size and overall market value. It also reveals trends that can be used to predict the relative growth or decline of a target market.

There are many reasons organisations seek new markets within which to operate. A market may become saturated or overcrowded. Or a market may be in decline with diminishing returns. Competition from a few dominating players may be too strong, effectively eradicating opportunities for others’ market share. Or demand for a product or service may have waned, making diversification necessary.

As well as seeking new markets for survival and continued sustainability, organisations are looking for new opportunities in order to grow. Business start-ups and innovators also need to identify and research viable markets in which to launch their fresh offerings.

The urgency of finding a new market and new opportunities varies depending on circumstances. It may be necessary to find a new market quickly in order to capitalise on a time-sensitive product or service. Conversely, you may have the luxury of waiting six months or more before launch. The attractiveness of opportunities varies and timing has a crucial role to play in maximising the potential rewards offered by a new market.

Undertaking detailed market research is essential in order to inform decision-making. Accurate, timely data will put you in the best position to gain an insight into your target sector and to determine whether you have identified the right market, at the right time, for your product or service to prosper.

This checklist provides guidance on researching new markets and covers issues to consider before contemplating market entry.

Action checklist

1 Be clear about the target market

Scope out the market or market segment you wish to investigate. For example, are you seeking:

- a new segment within your existing market

- a new industry

- a different geographical region

- an overseas market?

Also take into account whether you intend to market an established product or service to a new audience, or whether you are launching an entirely new product or service. Determining such criteria at the outset will give you a good starting point from which to begin your research.

2 Research the market and collect the data

Market insights need to be based on well-researched facts, not on vague assumptions or optimism. It is crucial, therefore, to undertake detailed market research in order to gain a sound understanding of the current state of the market.

Devise a strategy for data gathering and collation. Begin by determining what you want to find out and how you will go about finding it.

There are two types of information sources:

- Primary – information gained directly from individual sources, i.e. your target customers. Methods of acquiring primary data include interviews, surveys, questionnaires and focus groups. Decide who will be selected for your sample and how they will be contacted.

- Secondary – information that has been gathered by a third party and is readily available to consult. Secondary information is located in various places such as industry and sector reports, government reports, news reports, census data, company databases and the internet.

Consider the time, cost and resource implications before selecting your chosen methods. Also establish which sources will provide the most current and factual account of the market. Different approaches have their advantages and disadvantages, so think about how best to provide the answers you are seeking. Select your data gathering method: qualitative or quantitative (or both). Base your decision on what you want to find out and how the findings will be presented to others.

Remember that the business environment can change rapidly, so make certain that the information used to inform decision-making is accurate, current and valid. Also ensure that the information you gather is from a reliable, trusted source to increase the credibility and value of your facts.

3 Use existing networks and build new ones

Vital market information can also be acquired from an established network of industry experts. So look to your network to increase your knowledge of the current marketplace. If your new target market is similar to the one in which you currently operate, your existing contacts may provide useful insights into the market. Conversely, it may be necessary to establish new industry contacts to satisfy your knowledge needs. Take the time to identify key people in the appropriate fields and gradually build up a network of trusted people.

As well as helping you to learn about your new market through ‘insider’ knowledge, establishing relationships with industry experts at this stage will also help strengthen your position should you decide to enter this new market in the future.

4 Communicate with your customers

The development of social media networks has opened up opportunities for organisations to interact with customers and potential customers, and valuable intelligence can be gained in this way. Use your relationship with existing customers to find out what is not being provided by you or the wider marketplace. By talking candidly, you may discover opportunities to diversify into new markets to satisfy unmet needs or demand.

5 Keep track of what your competitors are doing

As well as your customers, you could also benefit from looking at the practices and growth strategies of your competitors. See whether they are diversifying their offering and whether this is helping them to enter new markets. If others have identified potential opportunities in different markets, consider whether you could be successful there too.

6 Analyse market trends

In times of rapid change, it has become increasingly difficult to produce credible forecasts. Nonetheless, it is still worth looking at past and current trends in your target market. Use the data you have gathered to help predict whether a market is likely to grow, plateau or decline and determine whether the trends indicate a change in customers’ current and future buying habits.

Market trends can be categorised in the following ways:

- Demographic – changing population patterns in different demographic groups such as age and ethnicity.

- Economic – fluctuations in the economy such as interest levels, personal income, taxation, etc.

- Sociocultural – trends in lifestyle activities and choices.

- Natural – trends in the changing natural environment, such as global warming, increasing scarcity of natural fuels, etc.

- Technological – trends in this arena change rapidly, with advances in technology having a far-reaching impact on numerous products, services and operations.

- Regulatory – changes to legislation and regulations.

Political changes and political stability can have a bearing on current and future demand for products and services. Use such trends to help predict buyer behaviour. Consider the trending areas and determine what impact they could have in the future. To what extent have they affected the market already?

7 Determine market size

To assess a market’s relative attractiveness and its potential to offer the opportunities you are seeking, you will need to calculate the overall market size and its current value. An estimation of current market size can be made by calculating:

- the number of customers or businesses it currently serves

- the aggregate spend by those customers

- the number of units being sold.

As well as determining the size of the current market, calculate what percentage of the market share you need to command to sustain or grow your business. A market may be large, but it may not be an attractive proposition if it is already filled with too many competing companies. Similarly, a smaller market may offer less growth in the long term but is also less likely to attract large competitors. Weigh up the pros and cons of each and decide what size of market fits your ambitions.

8 Evaluate growth potential

As well as calculating the size of the market, you also need to estimate its potential for growth over the long term. Use the current and future trending data you have compiled as a means of predicting the potential for the market to expand. Take heed of negative trends, as you do not want to be targeting a market that is already saturated and/or is showing signs of decline.

Compare the performance of the market as it stands today with its position 1–5 years ago. This should indicate a clear trend towards either growth or decline. If your market shows inconsistent performance over a five-year period, decide whether you think the level of risk is acceptable. If your target market shows signs of having reached a plateau, consider whether future forecasts indicate it is likely to increase in the coming years or whether the market has become exhausted and will naturally decline.

Remember that a market can grow rapidly only to plateau or decline shortly afterwards once demand has been satisfied. Determine whether your target market offers only a short-term advantage or has the capacity for prolonged growth.

9 Research the competition

If you have established that your target market is large enough to accommodate another entrant and is trending towards continued and sustained future growth, you may decide that it is an attractive proposition. However, when considering a new market you also need to take into account the players already operating within it. The pool of potential customers may be large, but the level of competition may be high.

Find out who your potential competitors are – both direct and indirect – and what percentage of the market they currently command:

- How many are there?

- Who are the market leaders?

- What threats do they pose?

- Do current players in the market allow ‘room’ for you to make your presence felt?

- Or is the market dominated by one or two companies which have commandeered the lion’s share?

Examine your positioning strategy and the differentiation that will set you apart from the competition. Porter’s five forces model may be a useful tool for considering your competitive position within a new market. The five identified forces can be used to determine the relative attractiveness of the market and whether you can successfully compete within it.

Consider the impact of the following:

- entry into the market of new competitors

- the threat of substitutes offering cheaper alternatives

- the bargaining power of buyers or customers

- the bargaining power of suppliers

- the level of competition from existing competitors.

Assess your own organisation’s position and rate each of the forces as favourable or unfavourable to determine how acceptable the target market actually is.

10 Identify new market threats

As well as competitors, identify all other perceived risks or threats posed by the new market. Your chances of success in a competitive marketplace will be threatened if:

- the market is fairly static, with little room for growth

- costs are fixed

- your product differentiation is low

- economies of scale are low

- competitor rivalry is fierce, e.g. competitors are undercutting each other in order to secure custom

- you lack the required skills and knowledge to compete

- you lack the required resources in terms of staffing, time and finances.

Contemplate the implications of potential risks and decide how these can be minimised. Risks may be overcome simply by making adjustments to your current operations, or by delaying the time of entry to a more opportune moment. Conversely, you may decide that the risks are simply too great.

11 Analyse the data and report your findings

Once all the information has been gathered and collated, the findings need to be carefully analysed, with rational conclusions drawn. The data will inform decision-making, so it is important to spend the time and effort needed to interpret the information. Remember to focus on the facts as they are presented – not what you want them to show. Although the findings may well reaffirm previously held assumptions about your target market, they could equally reveal something that you had not foreseen.

Adopt a consistent approach to recording and interpreting information so that it can be easily understood by others in the organisation. Devise a means of reporting the findings to senior management and other interested parties and arrange a time and date to present the information to them. Draw attention to the key findings revealed by your research and highlight the action points raised. Use the evidence to reach viable conclusions and support recommendations. Decide what the points of action will be and assign responsibility to see them through.

The findings of your market research are a valuable asset to your organisation, so be wary of distributing the results to external personnel.

12 Consider targeting a segment of a new market

Targeting a segment of a proposed market may be an attractive proposition to start-ups or small businesses seeking to begin operating on a small scale or targeting a niche set of customers. Although it is unlikely that capturing a segment of the market alone will be enough to grow a business or sustain it in the long term, it may be something you wish to consider if the business is young and looking to grow slowly. This can effectively keep you out of the eye-line of larger competitors, allowing you to develop reasonably undetected by your rivals. Once you have established a foothold, you may then be in a stronger position to compete in the overall market with the established players.

Determine the size of the segment and how fast it is growing (or declining). If you wish to expand your business in the future, find out whether the segment you are initially targeting will effectively provide entry into other market segments at a later stage.

13 Beware of being first to market

Be aware of the risks of targeting a new or newly emerging market. The first entrant to a market rarely ends up dominating it in the long term. Indeed, early entrants often expend time and effort building up an interest in the market only to be trumped by later entrants who capitalise on their hard work. So consider whether waiting for the market to become established will be more profitable for you in the long term.

14 Realise your return on investment

The time and costs involved in entering a new market are considerable. Typically, it takes 5–7 years before the prospects of a new investment are fully realised. You need to be confident that the market you have identified has the longevity to enable you to realise a return and that you will be able to gain sufficient market share to operate comfortably alongside your competitors.

As a manager you should avoid:

- failing to carry out thorough market research

- targeting a declining market

- dismissing unfavourable trends

- ignoring new market threats

- being first to market.

Scenarios are a projection of possible or imagined sequences of future events. They can be broad-ranging and contradictory. However, scenarios are not forecasts. They describe a series of events or changes that could happen, as opposed to asserting that something will happen. They are generally presented as stories formed around plots, highlighting the significant components of the future. Scenario planning involves elements of intuition as well as analytical approaches to gathering information and data.

Scenario planning is a set of processes for describing and evaluating scenarios. It helps business leaders to understand different possible futures and the internal and external factors that drive them, and to test strategies for dealing with these potential futures.

Successfully adapting to change is fundamental for a company’s continued growth and survival. To retain competitive advantage in an ever-evolving marketplace, organisations need to keep one step ahead of the competition. Regardless of whether change is predictable or unforeseen, it nevertheless should be planned for. Even planning for a known future is difficult, but how can you prepare your organisation for a future that is completely unknown? Answer: by using what is known and applying it in the creation of scenarios. Scenarios help managers prepare for the future by encouraging them to ask a series of what-if questions, considering several possible futures that may have a significant impact upon their organisation. This prepares them for eventualities before they actually happen. In this respect, scenarios complement more traditional forms of business planning and act as a form of contingency planning. Potential future break points in the marketplace that will affect the business are identified and response strategies can be prepared in advance.

Opinions differ as to the order of steps in the process of scenario planning and the weight to be given to each. The following checklist provides a general framework for developing and analysing scenarios.

Action checklist

1 Set objectives

To provide a sound structure for each scenario, set a framework of clear objectives. All parties involved in the creation of scenarios should agree on this process.

Ask questions such as:

- Where do we want to be in the future?

- What will it take to get us there?

- How long will it take?

- What could hinder us?

- What issues have caused us problems in the past?

- What do we want to avoid?

- How will we measure our achievement?

Pointers to consider include the following:

- Time projection – set a short- or long-term time horizon for each scenario.

- Business area coverage – scenarios can be projected futures of the organisation in its entirety or can focus upon specific areas or products.