Five Francs Each

Fred Vargas

Translated by Sian Williams

That was it, no chance of selling another one tonight. Too cold, too late, the streets were empty, it was almost eleven o’clock: Place Maubert, Left Bank, Paris. The man turned off the square to the right, propelling his supermarket trolley in front of him, arms outstretched. Bloody trolleys, they weren’t precision instruments. You needed strong wrists and you had to know all the blessed tricks of the one you were pushing to keep it going straight. Stubborn as a donkey, it wanted to roll sideways, put up a fight. You had to talk to it, shout at it, shove it hard, but still, like a donkey, it did let you carry round a lot of stuff to sell. Stubborn then, but reliable. He had called his trolley Martin, in honour of all those hard-working donkeys of the olden days.

The man parked his trolley near a lamp-post and padlocked it with a chain to which he had attached a large bell. So look out, any little shit who tried to nick his load of sponges while he was asleep, he’d get more than he bargained for. Sponges: he’d sold just five in a day, bad as it could get. A grand total of twenty-five francs, plus the six left over from yesterday. He pulled his sleeping-bag out of a plastic sack slung under the trolley, lay down on a grating over a metro vent, and curled up inside. You couldn’t go down into the metro station to keep warm, because it meant leaving the trolley above ground. That’s the way it is, you have an animal, you’ve got to make sacrifices. He’d never have left Martin alone outside.

The man wondered whether his great-grandfather, going from town to town with his donkey, had had to sleep alongside his beast in fields full of thistles. Not that it mattered, since he didn’t have a great-grandfather, or anyone else, nothing at all in the way of family. But you can always think about them. And when he did think, he imagined an old fellow with a donkey called Martin. What did the donkey carry? Salt herrings perhaps, rolls of cloth, or sheepskins.

As for himself, he’d trundled round plenty of stuff for sale. So much so that he’d worn out three trolleys in his time. This donkey was the fourth in a long line. The first to carry sponges though. When he’d discovered the sponge mountain, abandoned in a warehouse in Charenton at the east end of the city, he’d thought he had it made. 9,732 sponges, genuine sea-sponges, he’d counted them, he was good with figures, always had been. Multiply by five francs. You couldn’t ask more, because they didn’t look too appetising. Total: 48,660 francs, a mirage, a lottery win.

But for four months now, he’d been wheeling sponges from Charenton into central Paris and pushing Martin through every street in the capital. He’d sold precisely 512. Nobody wanted them, nobody stopped, nobody even looked at his sponges, his trolley, or him. The way it was going, it would take 2,150.3 days to clear the warehouse, that made 6.17 years dragging his body and his donkey around. He’d always had a good head for figures. But these sponges, nobody gave a damn for them, apart from five people a day. That’s not a lot, five people, bloody hell, out of the two million Parisians.

Huddled up inside the sleeping-bag, the man was calculating the percentage of Parisians who bought his sponges. He watched as a taxi stopped close beside him and a woman got out, slender legs, topped by a white fur coat. Not the kind of woman who would come into the percentage. Perhaps she didn’t even know what a sponge was like, how it swelled up and how you squeezed it. She went round him without seeing him, crossed the road, walked a little way along the opposite pavement and began to punch in the code in the doorway of a building. A grey car approached quietly, illuminating her in its headlights, and braked just by her. The driver got out, the woman looked round. The sponge vendor frowned, and tensed. He knew how to spot men who preyed on women, and it wouldn’t be the first or last time that he’d taken one on. Pushing awkward trolleys along pavements, he’d developed the fists of an all-in wrestler. Three gunshots rang out and the woman collapsed onto the ground. The killer ducked back inside his car, let in the clutch and drew away fast.

The sponge vendor had flattened himself as hard as he could on his grating. An old pile of rags abandoned in the cold, that’s what the murderer would have taken him for, if he had seen him at all. And for once, the man’s appalling invisibility, the fate of the disinherited, had saved his skin. Shaking all over, he scrambled out of his sleeping bag, rolled it up, and stowed it in the sack under the trolley. He went over to the woman and bent down to peer at her through the darkness. There was blood staining the fur coat, it made him think of a baby seal on an ice floe. He knelt down, picked up her handbag and opened it quickly. Lights went on in the windows above, three, four. He threw the bag on the ground and ran back to his trolley. The cops would be along any minute. They move fast. Frantically, he hunted through his pockets for the key to his padlock. Not in the trousers, not in the jacket. He kept searching. Should he run away? Abandon Martin? How could he do that to his faithful hardworking partner? He turned out all eight pockets, felt inside his shirt. The cops, oh God, no, cops with questions. Where were the sponges from? Where was the trolley from? And where was the man from? Furiously, he yanked at the trolley to try and pull it free of the lamp post, and the bell clanged in the night, merrily and stupidly. Almost at once came the sound of a police siren, running footsteps, and then the staccato voices, the cursed efficient energy of the forces of order. The man leaned over his trolley, plunging his arms deep inside the pile of sponges and tears sprang to his eyes.

In the half-hour that followed, a whole contingent of Paris police descended on him. On one hand he was important, the only witness of the attack, so they took some care with him, asked him questions, wanted his name, called him ‘vous’. On the other, he was just a stubborn old pile of clothes, and they were inclined to shake and threaten him. Worse, they were intending to take him to the station, on his own, but he clung with all his might to the trolley, saying that unless they brought his load with him, he wouldn’t breathe a word of what he’d seen, he’d sooner die. By now, there were arc-lamps in the street, police cars with their blue lights revolving, photographers, a stretcher, stuff everywhere, anxious murmurs, people phoning.

‘Take this guy to the station on foot,’ came a voice from not far away.

‘With his trolley full of garbage?’ asked another voice.

‘Yes, I’ll answer for it. Smash the padlock. I’ll be along in twenty minutes.’

The man with the sponges turned round to see what kind of cop had given this order.

And now he was sitting opposite him, in a sparsely lit office. The trolley had been parked in the police station courtyard, between two large cars, under the anxious gaze of its owner.

He sat waiting, hunched on a chair, a cardboard cup of coffee in one hand, gripping the plastic sack on his knee with the other.

Telephones had rung constantly, there had been all manner of coming and going, people hurrying, shouting orders. A general alert, because a woman in a fur coat had been shot. He was sure that if it had been Monique, the lady in the newspaper kiosk, who let him read the headlines every morning so long as he didn’t open the paper up, so all he knew about the world was a horizontal strip above the fold, never what was inside, well anyway, if it had been Monique, there would surely not have been ten cops chasing from one office to another as if the country was about to collapse into the sea. They would have waited calmly until their coffee break before ambling over to the kiosk to inspect the damage. They wouldn’t have been telephoning everywhere in the universe. Whereas for the woman in white, half of Paris had been woken up, it seemed. Just for one little woman who had never squeezed a sponge.

The cop sitting facing him had put down all the phones. He ran a hand across his cheek, spoke in a low voice to his deputy, then looked at the man for a long time, as if he were trying to guess what his whole life had been like without asking. He had introduced himself: Jean-Baptiste Adamsberg, commissaire of the 5th arrondissement. He had asked to see the man’s papers, and they had taken his finger prints. And now the cop was looking at him. He was going to question him, make him talk, make him tell them everything he had seen from down on the pavement. You could bet that was coming next. He was the witness, the only witness, an unlooked-for stroke of luck. They hadn’t shaken him once he was in here, they had relieved him of his jacket, and given him some hot coffee. Of course. A witness was a rare thing, a valuable object. They were going to make him talk. You could bet on that.

‘Were you asleep?’ asked the commissaire. ‘When it happened, were you asleep?’

This cop had a quiet, interesting voice, and the man with the sponges raised his eyes from his coffee.

‘Getting to sleep,’ he corrected him. ‘But someone always disturbs you.’

Adamsberg was turning his ID card over in his hands.

‘Surname Toussaint, first name Pi. That’s your name is it, Pi?’

The man with the sponges sat up straighter.

‘My name got smudged with the coffee,’ he said, with a certain pride in his voice. ‘That’s all that was left.’

Adamsberg looked at him without speaking, waiting for the rest, which the man recited as if it were a well-known poem: ‘On All Saints Day, so that’s my last name, my mother took me into the Social. She put my name on a big register. Someone took hold of me. Someone else put their coffee cup on the register. My first name got washed away, by the coffee, just two letters left. But ‘sex: male’ that didn’t get blotted out, bit of luck eh.’

‘It was meant to be Pierre, was it?’

‘There was just the first two letters,’ said the man firmly. ‘Maybe my mother just wrote Pi.’

Adamsberg nodded.

‘Pi,’ he asked, ‘have you been living on the streets long?’

‘Before, I was a cutler, went round towns selling my stuff. After that, I sold tarpaulins, cleaning fluid, bicycle pumps, socks, you name it. By the time I was forty-nine, I was on the streets, with a lot of waterproof watches full of water.’

Adamsberg looked again at the ID card.

‘Yeah, right, this makes the tenth winter,’ Pi finished the story.

Then he tensed, waiting for the inevitable barrage of questions about the origin of the goods. But nothing came. The commissaire sat back on his chair and ran his hands over his face, as if to iron out its wrinkles.

‘Ructions, eh?’ asked Pi, with the hint of a smile.

‘Ructions like you can’t imagine,’ said Adamsberg. ‘And everything depends on you, on what you’re going to tell us.’

‘Would there be ructions like that if it was Monique?’

‘Who’s Monique?’

‘The lady sells newspapers down the avenue.’

‘You want the truth?’

Pi nodded.

‘Well, if it was Monique, no, there wouldn’t be at all the same kind of ructions. Just a bit of a to-do, and a low-key investigation. There wouldn’t be a couple of hundred people waiting to find out what you’d seen.’

‘She didn’t see me.’

‘She?’

‘The woman in the fur coat. She just went round me like I was a heap of old clothes. Didn’t even see me. So why would I have seen her, tell me that? No reason, fair’s fair.’

‘You didn’t see her then?’

‘Just this heap of white fur.’

Adamsberg leaned towards him.

‘But you weren’t asleep. The shots must have roused you, surely? Three shots, that makes a lot of noise.’

‘Nothing to do with me. I’ve got my trolley to watch. I can’t be doing with everything goes on in the neighbour-hood.’

‘Your prints are on her handbag. You picked it up.’

‘I never took anything.’

‘No, but you went over to her after she was shot. You went to have a look.’

‘So what? She got out of a taxi, she went round the pile of clothes, that’s me, some guy drove up in a car, he shot at the fur coat, and that was it. Didn’t see anything else.’

Adamsberg stood up and walked round the room a bit.

‘You don’t want to help us, is that it?’

He had begun calling Pi tu.

Pi screwed up his eyes.

‘You called me tu!’

‘That’s what cops do. Gets us better results.’

‘So I get to call you ‘tu’ back?’

‘You’ve got no reason to. You can’t get any results, because you don’t want to talk.’

‘Are you going to start hitting me?’

Adamsberg shrugged.

‘I never saw a thing,’ said Pi. ‘Nothing to do with me.’

Adamsberg leaned against the wall and considered him. The man looked somewhat the worse for wear, what with hardship, cold, wine, all of which had worn grooves in his face and hollowed out his body. His beard was still partly ginger, cut with scissors close to his cheeks. He had a small girlish nose, and blue eyes deep-set in their sockets, expressive and darting about, hesitating between flight and a truce. You might almost imagine the man would put down his bundle, stretch out his legs, and they could have a chat like two old acquaintances in a train.

‘OK to smoke?’ Pi asked. Adamsberg nodded and with one hand Pi let go the sack, from which an old red and blue sleeping-bag protruded, to pull a cigarette out of his jacket pocket.

‘It’s a tear-jerker isn’t it?’ said Adamsberg, without moving from the wall, ‘Your story about the pile of rags and the pile of fur, the rich woman in her castle and the poor man at the gate. Do you want me to tell you what there is under the rags and the furs? Or can’t you remember any more?’

‘There’s a filthy geezer who’s trying to sell sponges and a clean woman who’s never bought any in her life.’

‘There’s a man in deep shit who knows a lot of things, and a woman in a coma with three bullets in her body.’

‘Not dead then?’

‘No. But if we don’t catch the killer, he’ll try again, you can bet on that.’

The man with the sponges frowned.

‘But why?’ he asked. ‘If someone attacked Monique, they wouldn’t try again next day.’

‘We’ve already established it wasn’t Monique.’

‘Someone important then?’

‘Someone very high up,’ said Adamsberg pointing with his finger at the ceiling, ‘not a million miles from the Ministry of the Interior. That’s why there’s all the fuss.’

‘’Well s’not my fuss,’ said Pi, speaking more loudly. ‘See if I care about the ministry and their business. My business is selling my 9,732 sponges. And people aren’t fucking buying my sponges. No one lifts a finger to help me. Nobody up there wonders how to find a way to stop me freezing my balls off in winter. And now they want me to help them? Do their job for them, help them out? Who’s got all those sponges to get rid of, them or me?’

‘Might be better to have 9,732 sponges to get rid of than three bullets in your gut.’

‘Oh yeah? You want to try it one night. Want me to tell you something, commissaire? Yes I did see something. Yes I did see the feller. And his car.’

‘I already know you saw all that, Pi.’

‘You do?’

‘I do. When you’re on the street, you always keep an eye open for people coming along, especially if you’re dropping off to sleep.’

‘Well, you can tell them up there that Pi Toussaint, he’s got sponges to sell, and better things to do than rescue women in white fur coats.’

‘What about women in general?’

‘She isn’t women in general.’

Adamsberg walked across the room and stopped in front of Pi with his hands in his pockets.

‘But don’t you see, Pi,’ he said slowly. ‘We don’t have to give a shit about what she is. Or about her coat, or the ministry, or all those people sitting on their backsides in the warm without thinking about yours. It’s their crap, their corruption, and it’ll take a lot more than a few wipes with your sponges to clear that lot up. Because that kind of dirt is so ancient it’s piled up in mountains. Mountains of sleaze. And you’re a fool, Pi. Want me to tell you why?’

‘I’m not bothered.’

‘Those mountains of sleaze, they didn’t get there by accident.’

‘Oh no?’

‘They grew up out of the idea that some people on this earth are more important than others. That they always have been, always will be. And let me tell you something: it’s not true. Nobody is more important than anyone else. But you believe it, Pi, and that’s why you’re as big a fool as all the rest.’

‘But I don’t believe anything, fuck’s sake.’

‘Yes, you do. You believe that woman is important, more important than you, so you’re keeping your mouth shut. But here, tonight, I’m just talking to you about a woman who’s going to die, nothing else.’

‘Bollocks.’

‘Every human life is worth the same as every other, whether you like it or not. Yours, mine, hers, Monique’s. That’s four of us. Add the other six billion and you’ve got the number of people who matter.’

‘Bollocks, just ideas,’ repeated Pi.

‘I make my living from ideas.’

‘And I make mine from my sponges.’

‘Except you don’t.’

Pi said nothing, and Adamsberg sat back down at the table. After a few minutes silence, he got up and put his jacket on.

‘Come on,’ he said, ‘we’re going for a walk.’

‘In the cold? I’m sorted here, it’s nice and warm.’

‘I can’t think unless I walk. We’ll go down into the metro. We can walk on the platforms, it helps ideas.’

‘Anyway, I got nothing to tell you.’

‘I know.’

‘And anyway, metro’ll be closed by now, they’ll chuck us out, I’m used to it.’

‘They won’t chuck me out.’

‘Privileged, huh.’

‘Yeah.’

On the deserted eastbound platform of Cardinal Lemoine metro station, Adamsberg paced up and down slowly in silence, his head bent, while Pi, a faster walker, tried to adapt his pace, because this cop, although indeed a cop, and determined to save the life of the woman in the fur coat, was, all the same, good company. And good company is the rarest of things when you’re pushing a trolley. Adamsberg was watching a mouse scurry along between the rails.

‘Tell you what,’ Pi said suddenly, shifting his sleeping bag from one side to the other, ‘I got some ideas too.’

‘What about?’

‘Circles. Ever since I can remember. Any kind. Like, take the button on your jacket, any idea what its circumference is?’

Adamsberg shrugged.

‘Can’t say I ever noticed the button at all.’

‘Well, I did. And I’d say, looking at that button, its circumference is 51 millimetres.’

Adamsberg stopped walking.

‘And what’s the point of that?’ he asked seriously.

Pi shook his head.

‘Don’t have to be a cop to work out it’s the key to the whole world. When I was little, in school, they called me ’Three-point-one-four’. Get it? Pi = 3.14. The diameter of a circle times 3.14, that tells you its circumference. Best thing in my whole life, that joke. See, it was a bit of luck really, that my name got blotted with coffee. After that I was a number, and not just any old number.’

‘I see,’ said Adamsberg.

‘You’ve no idea the things I know. Because Pi works with any kind of circle. Some Greek worked it out in the olden days. Knew a thing or two, the Greeks. See, your watch there: want to know the circumference of your watch, in case you’re interested? Or your glass of wine, see how much you’ve drunk? Or the wheel on your trolley, or your head, or the rubber stamp on your ID card, or the hole in your shoe, or the middle of a daisy, or the bottom of a bottle, or a five-franc coin? The whole world’s made up of circles. Bet you never thought of that, eh? Well, me, Pi, I know all about them, all kinds of circles. Ask me a question, if you don’t believe me.’

‘What about a daisy then?’

‘With petals or just the yellow bit in the middle?’

‘Just the middle.’

‘Twelve millimetres point 24. That’s quite a big daisy.’

Pi paused to let the information sink in and be properly appreciated.

‘Well, yeah, see,’ he said with a nod. ‘My destiny, that is. And what’s the biggest circle of all, the ultimate circle?’

‘The distance round the Earth.’

‘Right, I see you’re following me. And no one can work out the distance round the Earth without going through Pi. That’s the trick. So that’s how I found the key to the world. Course, you might ask where that’s ever got me.’

‘If you could solve my problem like you do circles, that’d be something.’

‘I don’t like its diameter.’

‘Yes, I’ve gathered that.’

‘What’s this woman’s name?’

‘No names. Forbidden.’

‘Oh? Did she lose her name too?’

‘Yes,’ said Adamsberg with a smile. ‘She hasn’t even got the first two letters of it.’

‘We better give her a number then, like me. More friendly than keep saying “the woman”. We could call her 4/21, four twenty-one, like in the dice game, because she was one of the lucky ones in this world. Well, till now.’

‘If you like. Let’s call her “4/21”.’

Adamsberg dropped Pi off in a small hotel three blocks from the police station. He went slowly back to his office. An emissary from the ministry had been waiting for him for half an hour, in a furious mood. Adamsberg knew him, a young guy, fast-track, aggressive, and just now shaking in his shoes.

‘I was questioning the witness,’ said Adamsberg, dropping his jacket in a heap on a chair.

‘You took your time, commissaire.’

‘Yes, I needed to.’

‘And have you learnt anything?’

‘The circumference of a daisy. Quite a big daisy.’

‘We haven’t got time to mess about, I think you’ve been made aware of that.’

‘The guy’s clammed up, and he has his reasons. But he knows plenty all right.’

‘This is urgent, commissaire, I’ve got my orders. Weren’t you ever instructed that any witness who’s “clammed up” can be made to talk in under fifteen minutes?’

‘Yes, I was.’

‘So what are you waiting for?’

‘To forget that instruction.’

‘You know I could take you off the case?’

‘You won’t get this man to talk by beating him up.’

The under-secretary banged the table with his fist.

‘Well, how then?’

‘He’ll only help us if we help him.’

‘What the hell does he want?’

‘He wants to make a living, sell his rotten sponges, he’s got 9,732 of them. Five francs each.’

‘Is that all? Well, we can just buy his fucking sponges outright.’

The undersecretary did a quick mental calculation. ‘You can have 50,000 francs by eight in the morning,’ he said, standing up. ‘And I’m doing you a favour, believe me, in view of your performance. I want that information by ten at latest.’

‘I don’t think you quite understand, sir,’ said Adamsberg without moving from his chair.

‘What do you mean?’

‘The man doesn’t want to be bought. He just wants to sell his sponges, all 9,732 of them. To people. To 9,732 real people.’

‘Are you kidding? You think I’m going to sell this guy’s sponges for him, send my officials round the streets?’

‘That wouldn’t work,’ said Adamsberg calmly. ‘He wants to sell his sponges himself.’

The under-secretary leaned over towards Adamsberg.

‘Tell me, commissaire, do this man’s sponges by any chance worry you more than safeguarding …’

‘Safeguarding 4/21,’ Adamsberg finished the sentence. ‘That’s her codename here. We don’t speak the name out loud.’

‘Yes, of course, that’s best,’ said the under-secretary, dropping his voice suddenly.

‘I’ve got a kind of solution,’ said Adamsberg. ‘For the sponges and for 4/21.’

‘Which would work?’

Adamsberg hesitated. ‘It might,’ he said.

At seven-thirty next morning, the commissaire knocked at the door of Pi Toussaint’s hotel room. The sponge-seller was already up, and they went down to the hotel bar. Adamberg poured out some coffee and passed the bread basket.

‘You should see the shower in my room!’ said Pi. ‘Twenty-six centimetres round, the thing at the top, gives a man a right whipping! So, how is she?’

‘Who?’

‘You know, 4/21.’

‘’She’s coming out of it. She’s got five cops guarding her. She’s said a few words, but she can’t remember anything.’

‘That’ll be shock,’ said Pi.

‘Yes. I’ve come up with a kind of idea in the night.’

‘And I’ve come up with a kind of result.’

Pi took a bite of bread, then felt in his trouser pocket. He put a sheet of paper folded in four on the table.

‘Written it all down for you,’ he said. ‘What the man’s ugly mug looked like, how he moved, his clothes, make of the car. And the registration.’

Adamberg put down his cup and looked at Pi.

‘You knew what the number plate was?’

‘Numbers, that’s my thing, told you. Always have been.’

Adamsberg unfolded the paper and glanced over it quickly.

‘Thanks,’ he said.

‘You’re welcome.’

‘I’m going to phone,’

Adamberg returned to the table a few minutes later.

‘I’ve passed it on,’ he said.

‘Course, once they’ve got the number, it’ll be easy for you people. You should pick him up by the end of the day.’

‘I had this kind of idea in the night, about selling your sponges.’

Pi pulled a face and drank some more coffee.

‘Yeah,’ he said, ‘so did I. I put them in the trolley, I push it round for a few years, and I try and get people to buy them at five francs each.’

‘A different idea.’

‘What’s the point? You’ve got what you wanted to know. Was it a good idea?’

‘A bit odd.’

‘Some trick a cop might dream up?’

‘No, just a trick anyone might dream up. Give them something for their five francs.’

Pi put his hands on the table.

‘They’ll get a sponge! Do you take me for a crook or what?’

‘Your sponges are pretty grotty.’

‘Well, what are people going to do with ’em? Squeeze them in dirty water, that’s what. No fun being a sponge.’

‘You give them the sponge, plus something else.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like getting to write their name on a wall in Paris.’

‘I don’t get it.’

‘Every time someone buys a sponge from you, you paint their name on a wall. The same wall.’

Pi frowned.

‘So I have to stay there, by this wall, with the goods?’

‘That’s right. In six months, you’ll have a big wall covered with names, a sort of massive great manifesto by spongebuyers, a collection, practically a monument.’

‘You’re a weird guy. What the fuck am I supposed to do with the wall?’

‘It’s not for you, it’s for the people.’

‘But they couldn’t give a toss, could they?’

‘No, you’re wrong about that. You could have them queuing up at your trolley.’

‘What’s in it for them, tell me that?’

‘It’ll give them some company and a bit of existence. That’s not nothing.’

‘Because they don’t have any?’

‘Not as much as you think.’

Pi dipped his bread in his coffee, took a bite, dipped it again.

‘I can’t make up my mind if it’s a fucking stupid idea, or a bit better than that.’

‘Nor can I.’

Pi finished his coffee, and folded his arms.

‘You think I could put my name there too?’ he asked, ‘Down the bottom, on the right, like I was signing the whole caboodle, when it’s finished?’

‘Yes, if you want. But they have to pay for the sponges. That’s the point.’

‘Of course, they bloody do. You take me for a conman?’

Pi thought some more, while Adamberg was putting on his jacket.

‘Yeah, but look,’ said Pi. ‘There’s a catch. I don’t have a wall.’

‘Ah, but I have. I got one last night from the Ministry of the Interior. I can take you to look at it.’

‘And what about Martin?’ asked Pi, standing up.

‘Who’s Martin?’

‘My trolley.’

‘Oh, right. Well, your trolley’s still under the watchful eye of the cops. He’s having an exceptional experience that will never be repeated. Don’t bother him for now.’

At the Porte de la Chapelle in northern Paris, Adamsberg and Pi considered in silence the gable-end wall of an empty grey building.

‘That belongs to the State?’ asked Pi.

‘They weren’t going to give me the Trocadero Palace.’

‘No, s’pose not.’

‘As long as you can paint on it,’ said Adamsberg.

‘Yeah, a wall’s a wall, end of the day.’

Pi went up to the building and felt the surface of the coating with the flat of his hand. ‘When do I start?’

‘You can have some paint and a ladder tomorrow. After that, it’s up to you.’

‘Do I get to choose the colours?’

‘You’re the boss.’

‘I’ll get some round paintpots then. Some diameters.’

The two men shook hands, but Pi pulled a worried face again.

‘’You don’t have to do it,’ said Adamsberg. ‘It might still be a fucking stupid idea.’

‘No, I like it. In a month, I might have names up high as my thighs.’

‘What’s bothering you then?’

‘4/21. Does she know it was me, Pi Toussaint, who nabbed the bastard that shot her?’

‘She’ll be told.’

Adamsberg walked away slowly, hands in pockets.

‘Hey,’ cried Pi. ‘Do you think she’ll come? Come and buy a sponge? Get her name up here?’

Adamsberg turned round, looked up at the grey wall, and spread his arms in a gesture of ignorance.

‘You’ll know if she does,’ he called. ‘And when you do, come and tell me.’

With a wave of his hand, he walked on.

‘You’re going to be writing history,’ he murmured to himself, ‘and I’ll be along to read it.’

Translator’s note

‘Five Francs Each’ is published here for the first time in English. It was originally published in French in 2000 – a year before the appearance of The Life of Pi by Yann Martel.

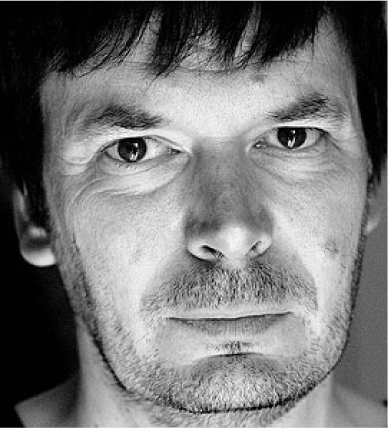

IAN RANKIN was born in Cardenden, Fife, in 1950. Before becoming a full-time novelist he worked as a grape-picker, swineherd, taxman, alcohol researcher, hi-fi journalist, college secretary and punk musician, in London and then rural France. He is best known for his Inspector Rebus novels, set mainly in Edinburgh, and adapted as a hugely successful series on ITV. In 2013, Rankin co-wrote the play Dark Road with the Royal Lyceum Theatre’s Artistic Director Mark Thomson. He lives in Edinburgh with his wife Miranda and their two sons.