Face Value

Stella Duffy

It’s not about me.

I used to say that all the time, at first when the fuss happened, when it took me from promising to promised, from potential to arrived, when everyone wanted to know who I was and where I’d come from, I said it as my stock answer.

It’s not about me.

Because it was true, it wasn’t.

Later, in interviews, quite possibly hundreds of interviews at the time of the retrospective, the same old questions, all over again, I said the same, all over again. Or at those stupid parties where I was only in attendance to promote my career, to assist my agent, to do the right thing by the person they’d decided I was, at the events there was always some oily man who’d think it was flattering to contradict my stock answer, to correct me, with an ‘Oh but come on, surely you can admit it now …’

I’m admitting it now.

It was not about me.

They’d ask too, sitting around the dinner table with friends, this workmate of that gym-buddy, this father of that child at school. I noticed, when I was younger, as a non-mother, that the school-gate friends of my friends were the worst. They had nothing to talk about but their children, and even the most besotted parent runs out of child-praise eventually. Halfway through the second bottle, house prices, the government, and the cost of the child-minder covered, the increasingly desperate conversation would finally turn to me.

You don’t have children?

What do you do?

And then –

Oh. You’re her. You did that piece.

For God’s sake. I did about four dozen others, each one of them massively successful, along with a hundred or more less well known, and another couple of hundred that never saw the light of day beyond my studio. But yes, I made that piece. And no, it’s not about me.

Maybe I wouldn’t mind if they were also interested in the rest of it, the paintings and the tapestries I worked on next, the miniatures I’ve been making for over a decade now, even the films, self-revelatory as they are. The films are about me, intentionally, deliberately, they are self-sacrificing, self-offering, in a way that nothing else I have made has been. Which might explain why they’ve not been as successful. Something about the giving up of self, too readily, that doesn’t sit right with the viewer. The viewer wants to feel they have prised us from our shell, found the pearl hidden in the gritty oyster. When I offered my pearls, strand by strand, reel by reel (it was film, not video, for some things I am a purist), there was – oddly – less engagement for the viewer. Well, there it is. I have had to accept that not all of my work is received in the same spirit it is offered. I took a while to learn, but I know it now.

I hasten to add, it’s not at all that I dislike talking about my work. I’m happy to do so, just not that piece. And because I’ve been so open about it, because I’ve said time and again in interviews, that I will talk about anything but that, because I have not lied, not once, when I have discussed my feelings, my lack of feelings, my choice never to speak of it – that is, inevitably, what it always comes back to. The one journalist, interviewer, fan, who is sure that they will force me to reveal all. How it made my career and then broke me. How I went a little crazy for half a year or so after that exhibition. How it changed my life.

I did not change my life. It wasn’t about me.

I have been an artist for just over fifty years. I have a well-respected, widely sold, widely collected back catalogue. I am known, wanted. Yet of all the work I’ve ever made, it’s always that bloody piece that they come back to – and they will insist on asking about it, all of them. All of you. And so, because it is the truth, and because I know I can never get you to shut up and leave me alone if I just refuse to answer at all, I generally say something like: But what no-one ever understood, is that it wasn’t about me.

Then there they are, the almost-winks, the smug insinuations, the little knowing grin that what I’m really revealing is how false we artists are, how blind to our own truths. I am offered the smile that suggests, no matter how honest an artist endeavours to be, that we are never fully revealed in mere words, that we show so much more in our self-deluded hiding than we do in the truths we try to speak.

In short, they – you – do not believe that I do not want to talk about it. They – you – do not believe that they don’t understand the piece and never have done.

I’m telling you now, once and for all, it was never about me.

This is why.

She was nineteen when we met, I was twenty-five. Now, at sixty-four, that six-year gap between nineteen and twenty-four seems nothing, but come on, don’t you remember how adult you felt at nineteen? And then how, by our mid-twenties, nineteen – all the teens – seemed an age away, the love earned and lost, the passion experienced, the agonising, ecstatic growing up that had gone before, that had changed our DNA.

So, she was nineteen and I was her senior by every bit of six years. She was being paid very little by my agent to come over and help me out a bit – my agent’s phrase, not mine. My agent’s idea, not mine. I’ve always guarded my privacy, even back then I didn’t want anyone in the studio, couldn’t bear the idea of someone watching as I worked. I have always wanted a clean line between process and product. The market didn’t like the separation then, and they like it even less now, when artist and artwork have become so inextricably linked that buyers believe they are getting a piece of you when they hang you on the wall, when they make space in the foyer, when they build a room just for the work.

Oh yes they did. They created a room just for the work, my work. Astonishing. I was twenty-five – dear God I was young, and I was good. Young and good, there is no more potent combination. True, money is handy, money is useful, but when you’re young and talented, money is a sideline. It’s only with age that we come to understand its true worth. Someone – someone malleable, amenable, needy (someone my agent could pay, my agent being old enough to understand the true value of money) – came up with the astonishing idea of creating a room for my work. It took a little persuasion, or maybe a lot, I wasn’t involved in the negotiations then, I don’t involve myself in them now. Process/product. Keep them apart. In the end, the gallery owners, in collaboration with a middle-aged architect keen to show he wasn’t yet past it, decided to use the occasion of my first major exhibition to extend the gallery. Yes, it may have been an idea that was pending, my work may have been just the excuse they needed to demand their Board agree to a bigger spend, or perhaps the architect paid, and certainly my agent fucked. Whatever happened behind the scenes, the effect was that they made a new space specifically for, informed by, my first ever exhibition. They changed a building for me.

They took out two walls, lifted the ceiling, opened a room that had been all about artificial light, proud of the artifice of its light, and made it about the day and the night, and the difference between the two. My work in daylight, sunlight, rainlight, from five until nine – this was a summer exhibition, we considered autumn but dead leaves turn to mulch, and no-one wants chill winds at an opening. The people we wanted to come, to buy, were all about showing themselves, we couldn’t be handing out scarves as they entered the building, so summer it was. And there was also my work in sodium yellow – we kept the space open twenty-four hours a day. I know it happens all the time now, but not back then, forty years ago you understand, we were new, brand new. We were a happening for the rich and comfortable. They so wanted to be happening, they just didn’t want to have to wear batik. Neither did I.

With the exhibition running twenty-four hours a day, I practically moved in. I needed to, in many ways the exhibition had me as the centre-piece.

It wasn’t about me.

When I say they removed a wall, I mean a wall, the entire back wall of an otherwise ordinary 1960s space, and replaced it with steels and raised glass balconies. One end of the room entirely open to the elements. And even though we’d chosen the season to allow for weather, it was an elemental summer, wind, rain, hail and a solid week of stifling heat. Astonishing. Of course, at twenty-five I thought I deserved it. I thought it was all for love of my work. It was many years before it occurred to me to consider who my agent had had to pay, to fuck, to make my break. And longer still before he agreed to tell me. (You don’t want to know.)

Meteoric rise to glory, the bright star from nowhere, art world’s hottest new thing. And my poor agent half-broken by the actual, physical, fuckable price he’d had to pay to get me started. Well, I’ve been paying him ever since. Fifty percent. There’s always a ferryman who demands a silvered palm.

I had been working for ten years by the time of that exhibition. Taking my work seriously for ten years. Yes, I did start young, so do many artists. Unlike most of them, I made sure to trash my youthful work, my pathetic teenage experiments, whenever I found a better way, a more successful method. There was no path to be followed through my attempts, no archive to trawl and say see, she went from this to that, here to there, and finally made her way to now. Even then, on the brink of my first exhibition, there was simply a collection of finished work, each piece complete and whole in itself, every one a work of art. And today there is not a single drawing, sketch, first mould, half-cast, Polaroid in my archive.

(OK, there is, one, a Polaroid, I’m getting to that. It’s not about me.)

So. The exhibition was a few months away, they were halfway through tearing down the wall, I was getting daily reports from my agent about how it was looking, how it was going to look. He thought they were pep talks, would gee me up to get on and make, to provide the matter to fill the space, to be the Artist. In reality he was screwing me up. Totally. Terrifying me that they’d actually gone along with the absurd idea, were spending so much time and money and effort on making a space for my work (not for me, it’s not about me), and it was all making me a bit crazy. Crazy worried, crazy nervous, crazy upset. They knew the work I’d done to date, there was already a draft catalogue of the pieces I had to show, the work, that was what they wanted, they were all excited and my agent didn’t understand why I wasn’t thrilled. But it wasn’t what I wanted. Not yet. There was something missing, something extra, the thing that would make it fly. And I’d been gnawing away at this lack of the one thing.

I didn’t believe in me in the same way my agent did, not yet, not back then. I understood that he saw promise, I understood this exhibition was not to be that of a finished artist, but of one at the peak of her beginning, ready to soar. I understood this, and still I wanted that one thing, the piece that would tip it over into glory. Tip me over. I was exhausted, stressed, I was upset and sobbing on the phone to my agent every half hour – in the time before mobile phones, you understand, when the telephone was a shrill interruption held in place by wires and cables, not a welcome distraction from a dozen other screens.

And so, no doubt to get me off his back, he came up with the brilliant idea of getting an assistant for me. Someone to help with the basic things. Basic things like getting me out of bed before three in the afternoon, basic things like getting me into bed in the first place. Basic things like stopping me destroying all the pieces that had already been assigned places in the exhibition catalogue. In a fit of insomniac insanity, I’d decided they were shit, I was shit, and this exhibition was going to show the whole world my true, talent-free nature.

I may have been twenty-five, but I had the amateur-dramatics of a teenager.

And so she arrived. The assistant-nanny-saviour. The one who was to make all the difference.

Didn’t she just.

She was, how shall I put this? Oh yes, perfect. No really, she was. And I don’t mean in a Mary Poppins kind of way. She wasn’t there to look after me, not really. Nor was she an All About Eve kind of assistant. There was no hidden agenda, no – as my mother would have it – ‘side’ to her at all. She was just perfect. She had a way of making me feel that I could do anything. She behaved as if it was the most natural thing in the world for my work to be getting this attention, that it made absolute sense that the whole open-to-the-elements thing was going on – and this despite the rumours of how much it was costing and that the gallery owners were kicking themselves for agreeing to my agent’s absurd demands, conveniently forgetting they’d wanted the renovations, as we always do when confronted by the dust, the brick, the gaping hole in the roof. She made me feel good about it all. She – I can’t go on she-ing her, can I? Very tedious for you. So, the assistant, let’s call her Lileth. I never use her real name, not now. She didn’t like it anyway, her real name, said she’d only used it half a dozen times since she was twelve, had picked a new name every few months and demanded her family try it out. So she might as well have been called Lileth, might as well be now.

Lileth was a god-send. She simply made everything better.

And I loved her for it.

Not in love, I am not gay, not that I’ve discovered anyway. I’m not really anything much, never have been, I don’t have the energy for other people, not when my work demands so much of me. I know I sound like a cliché, can’t be helped, it’s true. I have tried relationships and I have always been found wanting in them. I cannot give enough because I would rather be in my studio. I cannot agree to be at a dinner at a certain time because I would rather be working. I cannot agree to be with you in bed because, if you help prise me from my work and lift me away from the matter in hand, the in-bed in hand, then there is every chance that finally unfettered from the mundane, I will begin to dream another piece of work. It is only when I am away from the work in hand that I can begin on the work in my head.

Well. Lileth.

Lileth fixed it. She turned my fear into courage, my worry into work. Instead of placating me, Lileth cajoled and spurred me on. Where others told me to sleep, she would say, Fuck sleep. Get on with it. Who knows when you’re going to die? Keep working.

She would bring me food and coffee and wine and a little coke, just a little coke, to keep me up, keep me on it.

Work bitch work.

Our little joke.

Eat bitch eat. Drink bitch drink. Die bitch die.

Lileth was astonishing. She was just right. And the exhibition, when it finally came, when the gallery delays and building permits and problem after problem had been overcome, when that day, that night, that incredible night finally came, it too was astonishing. It too was just right.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Even with Lileth on my side, there was still the problem of that piece. The one that would make it fly, the one that would hold it all together and also alarm, shock, slap, that would emerge from the whole and be the whole. That piece. The one I was dreaming, looking for, digging into my guts to find and not … quite … getting it.

And then, I got it. I totally got it, I so got it, I was there when it was got, by me, getting it.

I know, you don’t expect ladies of sixty-something in your stories to talk about ‘getting it’. That’s because you have us in the realm of the grey, where ‘old folks’ perpetually sing It’s a Long Way to Tipperary and talk about the war. Fuck off. I was born in the fifties. I’ve taken more recreational drugs – and never pretended I didn’t like them or that they ‘did nothing for me’ – shagged more men, and I have delighted more strangers, than you’ve had hot dinners.

I do not bother with hot dinners. Hot dinners are the enemy of the waistline.

I got it. The idea, that idea, the one all the pictures are of, the photographs. The idea that has been used for other people’s art, for their photo-shoots, their shop windows, their art-house films and once, God help me, for that bloody awful play where they made all the ushers dress like me.

We made the waitresses dress like me.

It wasn’t about me.

Yes, yes, I know you’re so cool you have no idea what I’m talking about, do you? You are too young or too uninterested in art, or too … God knows, net-savvy. Very well, let me sketch you a picture. Trust me, I’m an artist.

You approach the venue. You know you are approaching the venue because since you turned the corner you have seen me. Every second person you have seen is dressed like, made up to look like, looks like me. At this time in my life and in yours, you have no idea what I look like, but here they are, these young women each one 5’5’ tall, each one weighing 110–112lbs and not an ounce more, each one in a long black wig, a deep red dress, absurdly long eyelashes, painted-on eyebrows, and where everyone at the time was wearing nude, nearly-nude, some insipid shade of hippy harmony on their lips, each of these girls wore a gash of dress-matching red. They were barefoot and their toes and fingernails matched, blue. There were black girls, white girls, brown girls, Asian girls, Oriental. And a few boys who looked like girls. Daring.

And I was one of them.

I was dressed up, made up, designed-up, covered-up to look exactly like all of the girls. The girls who directed you to the entrance, who offered you a drink, who handed you the catalogue, who scuttled back and forth along the street, up the stairs, to the walls where they placed those lovely, lovely red dots. I looked just like one of them.

See? Told you it was not about me.

And in the space itself, the space that we finally allowed you into, having left you queuing in the street for a whole half hour, in the space with mannequins dressed like us flying above, with versions of me sitting high in the trees in the garden in the outside that was inside, in the centre of the room, there she lay. Lileth as me, in the glass coffin, the formaldehyde-filled coffin. The woman who was me who was dead who was living. Who was not me. See? It’s not about me.

(No I don’t think either Tilda or Damien ‘improved’ on my work. No I do not.)

It was magic, of course. Something to do with mirrors and a very very thin pipe that kept oxygen flowing into her nose and mouth. She was bloody good though, you had to stand very close and watch for some time to see the slightest flicker of an eye lash or a raise of her chest. Almost there, not there. And most people didn’t bother to look. They saw the mannequins above, the models in the street, the versions of me/not me climbing the trees outside, looking down at us from the all the windows overlooking that now-open back lot. It was a wonderful idea. And it really worked.

They thought I was terribly clever.

They still didn’t know what I looked like.

I was dressed up too, of course.

And then.

My agent stands on a chair to make a speech. He is a small man, and – in the manner of small men – fastidious, fussy, absurdly picky about personal hygiene – which is what, I think, was so painful for him, the things he was asked to do, the things he did, for me, to get me there. Here. I am here and so is he. We have a signal. I hope she sees it, we have rehearsed this, but never with so many people around, we could never have got away with the secret if there were so many people around.

He stands on a chair to make a speech. He begins and I zone out. I have heard the speech, Lileth wrote the speech, they both rehearsed him in it, I am nervous and so I zone out until my cue. Here it is, here it comes.

The absurdly talented …

And as I begin to walk towards him, as the room begins to make way for me, as I reach my hand up to the wig to reveal I am she, the one they have been looking for, that of all these women (and some men) it is me who has made all this, up steps Lileth.

Out of the glass coffin. Out of the formaldehyde (not really, we found something that had the same viscosity, the smell).

And now there are two of me.

Wet me and dry me.

And now the waitresses and the assistants and the mannequins – who were never fake, never plastic, who have been harnessed there on wires for hours the poor things – now we all reach up a hand to pull off the wig and then.

Lileth walks to me and I walk to her.

And I pull the wig from her head, I rip the dress from her shoulders, I use the dress as a cloth to wipe the gash of lipstick from her face and Lileth is me.

Naked. Shown. Exposed. Exhibited.

She turns and does the same to me and there we are. Identical down to the tattoo above our left breasts. A half heart each. Same, not mirror, that would have told a different story.

And that was it. The room erupted as you might expect, as you have been led to expect by every cynical, copycat show that has since copycatted ours. We were the first copies. I was handed a lovely silver gown, Lileth was escorted off to wash and dress, the evening continued.

And someone wanted to buy the girl in the coffin.

And someone bought the girl in the coffin. He signed a cheque there and then, the figure made up by my agent, made up by him on the spot because he didn’t think he could get away with it and has been kicking himself ever since, since he’s worked out he could probably have asked for double, treble, since the piece has sold and sold and sold. Every time it is sold on to the next proud and hungry collector, I get a little more fame, and all the others of my pieces go up in value. It helps with the few I kept back for me, the one or two I gave him. But neither of us get a percentage of the original, copy-right. And we were all in on the joke, the whole room in on the joke.

(Not Lileth, she was off showering, washing the stink of the heavy water from her skin, breathing deep. Drying her hair, putting on a nice frock, her own makeup, readying herself for her big entrance, her re-entrance, the entrance where they wouldn’t notice her at all.)

they didn’t notice her at all

so no-one knew what she looked like really

and she was young

and she didn’t quite fit in

and she didn’t know how to be with those people

It wasn’t too hard to give her one drink and another and another. It wasn’t too hard to make sure one of those drinks was laden with a dose that would knock her out, lock her out of herself.

And it wasn’t hard …

Yes. It was actually. I liked Lileth. I really liked her.

But we had made a deal. Not the buyer and me, the agent and me. We had this idea and we made this deal. I wanted it to be astonishing, I wanted it to fly. I didn’t need everyone who came to the exhibition to see how truly astonishing it was, underneath, in reality. I just needed to know that for myself. I needed to know I was making a difference.

Don’t all artists want that? To make a difference? To put their stamp on eternity. And what greater stamp is there than to stop another?

Yes, there was a Polaroid. It is of that moment. I do not gloat in it, revel that it was taken, he and I took it together. What do you call them now? A selfie? There is a selfie of he and I holding Lileth. We are holding her on the table as her blood drains out.

My agent was a taxidermist once. In another life. He is not a young man now and even then, he was already middle-aged, had done so much. Lived many lives. In one of them he was a soldier in a far-away country. In another, he was a taxidermist. And in this one, here, he was my agent. And he knew, even before I knew, what I wanted.

In the moment of passing, the point where the blood went from just enough, to just not enough, we were posed. Ready. He clicked the switch.

I have never been very successful with photographs. People like my installations better, my sculptures. They have said, unkind critics have said, that my photographs are a little flat, as if the life is just a little less in them. They may be right.

We took a Polaroid of the one Polaroid, and then another, and then we had one each. Me, him and Lileth. He had one to keep as evidence against me, I as one against him. The third sits in the small of her back, beneath the waistband of the red dress, perfectly preserved. As she is.

You’d be surprised how long a punter is prepared to wait for their merchandise, once they know they have it, once they have been on all the art pages as having it, he waited a good three months before we were ready to deliver his goods.

She is great art. She is so life-like, they say.

No, she really isn’t.

She explains our mortality to us, they say.

Well, she explains her own.

She is you and me.

No. She is herself. She is nothing like me. Though we made her up like me, the wig, the dress, the makeup. We made her up like the made-up me.

And she floats in his gallery. You can pay to see her. He does not allow free visitors. He keeps the light a little low. Too low. And sadly, so sadly, there are no windows, no wind or rain. She floats in no water and she reminds me, when I think of her, of a time and a place. That is all. A time and a place where I had one astonishing, audacious idea.

And I executed that idea.

I forget her name. I worked hard to forget her name. I call her Lileth. It suits her.

That collector, the one who is as famous for collecting her as he is for anything else, he has never understood what he paid for, what his zeros bought him. He speaks about her with a pomposity that is almost shocking in its stupidity. About the symbol she is, about the hope she gives him, hope of a form of life after death, hope that humanity can one day understand itself through the image of itself. Art-school bollocks. She is a dead woman in a box of liquid. I gave him hope. (And no, there is no life after death. There is just death. Look at her.)

Although the money was useful, the fame, the notoriety probably made more difference. And anyway, we did not do this to make money, my agent and I. We did it because we could. Because it would be art, real art, living art.

We did it for art’s sake.

I called it Me/Not Me.

It was never about me.

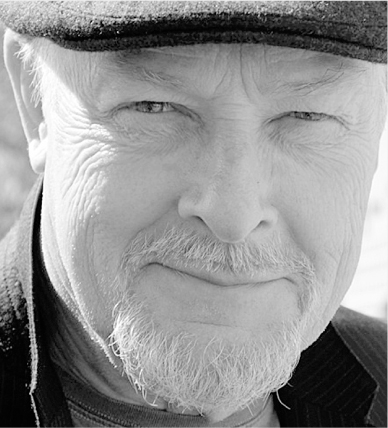

JOHN HARVEY, born in London in 1938, is best known for his jazz-influenced Charlie Resnick novels, set in Nottingham. Lonely Hearts, was named by The Times as one of the ‘100 Best Crime Novels of the Century’; the twelfth and final novel in the series, Darkness, Darkness, was published in 2014. He has published more than 90 books and in 2007 was awarded the Crime Writers’ Association Cartier Diamond Dagger for Lifetime Achievement.