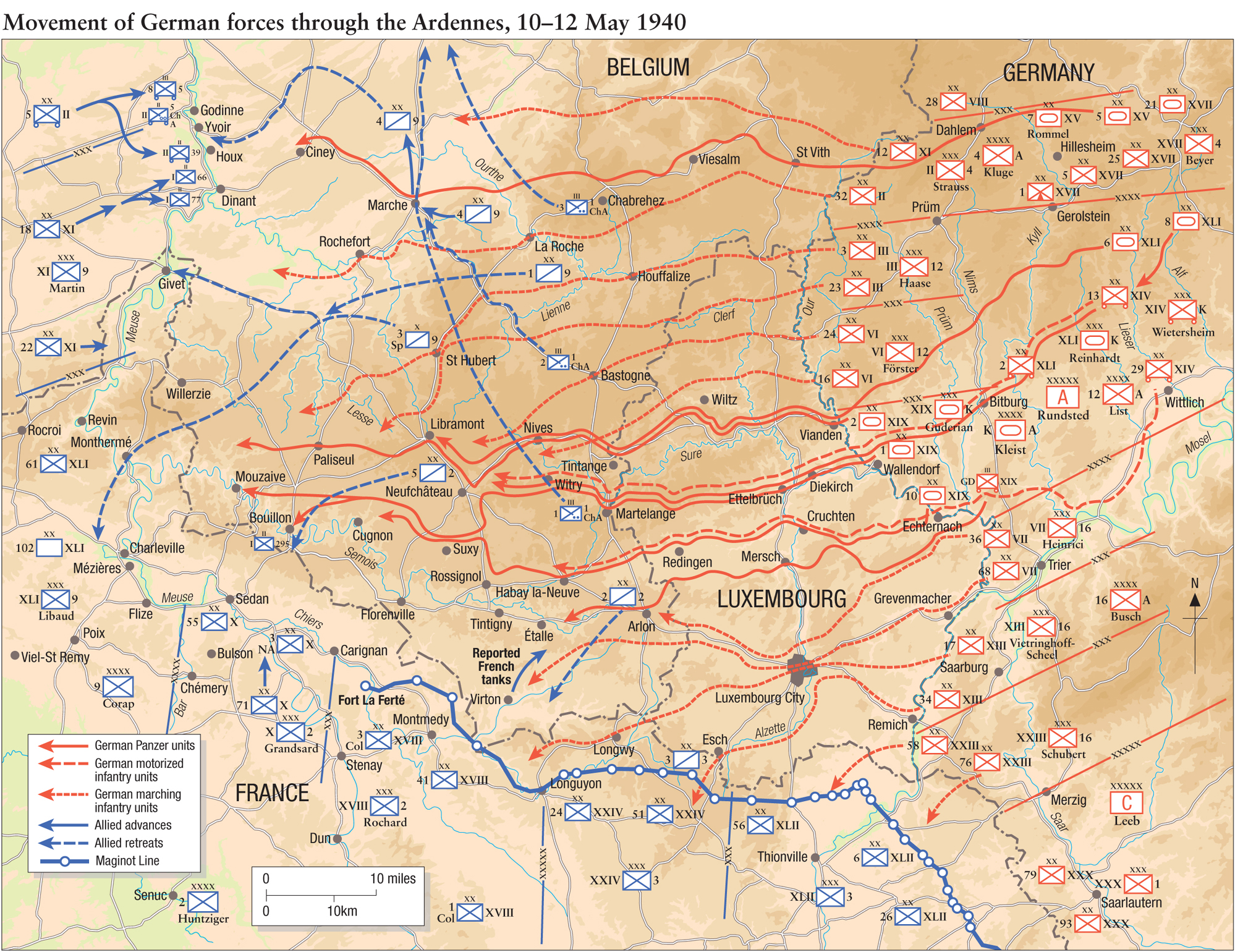

As long as we make special provisions if any enemy attacked [through the Ardennes] he would be pincered as he left the forest. This is not a dangerous sector.

Marshal Philippe Pétain, Address to Senate Army Committee, 14 March 1934

At 0245hrs CEST2 the first of some 500 Luftwaffe twin-engine bombers lifted off from their German airfields, took 45 minutes to gather into their attack formations, and within an hour began crossing the frontier headed for their targets: 72 airfields in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. In the north, Luftflotte 2’s dawn attacks were largely effective, destroying some 190 French, Belgian and Dutch aircraft.

In Heeresgruppe A’s area, Sperrle’s initial effort was less consistent. I. Gruppe/Kampfgeschwader 1’s (I./KG 1) raid on Cambrai-Niergnies decimated one ZOAN fighter group (GC III/2; air cover for Général Georges Blanchard’s 1ère Armée), destroying eight MS 406s and damaging five more so seriously that Général Têtu had to transfer another unit (GC III/7) from ZOAE to replace it. Other Heinkels destroyed seven Potez 63-11 and Bloch 174 reconnaissance aircraft (GR II/33 and GR II/36) while Do 17Zs knocked out five Am 143 bombers (GB II/34) and six Fairey Battles, as well as caused serious damage to hangars and workshops at three AASF bases.

The Allies’ fighter forces were otherwise unscathed, fully alerted, and began launching 363 AdA and 178 RAF fighter sorties, meeting the Luftwaffe’s second wave – another 500 twin-engine bombers that took to the air at 0415hrs – in a vigorous and ferocious defence. These, plus the third wave – another 500 bombers, launched in the afternoon – struck 17 rail centres, 16 factories and military camps, and 45 communications centres, headquarters, and permanent fortifications in France, but losses were heavy.

Sperrle’s initial failure cost him 40 bombers. Half of these were Do 17Zs. Kampfgeschwader 3 lost 14 Dorniers to Curtiss H-75s (GC I/4 and GC I/5) and AASF Hurricanes (1 and 73 Sqns) while KG 2 lost a further half dozen to Hurricanes (1 and 87 Sqns) and GC I/5’s Hawks. Hardest hit amongst the Heinkel Gruppen was I. Fliegerkorps’ III./KG 1 which lost six bombers – and their commander – in an unescorted raid on the Potez aircraft factory and surrounding airfields at Albert. Similarly V Fliegerkorps’ III./KG 55 lost its commander and four He 111Ps to French fighters (GC I/2 and GC II/4) defending Nancy-Essay airfield.

Taking off at dawn from Aschaffenburg airfield, 25 miles southeast of Frankfurt, Oberleutnant Oskar Reimers, commander of 4. Staffel/KG 2, led his nine Dornier Do 17Z-2s at very low altitude, heading west. Crossing the French frontier south of Sedan, the formation of three Ketten (three-aircraft ‘vics’) flew down the Aisne River valley, passing to the north of Reims, before swinging round to the left at the Aisne–Marne Canal to approach their target from the north-west.

Their target was Condé-Vraux, an RAF Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) airfield approximately 25 miles south-west of Reims, where 11 Bristol Blenheims of No. 114 Squadron were ranged upon the aerodrome, armed and fuelled, waiting for their aircrews who were just finishing their morning mission briefing. Ordered to attack the bridges spanning the Albert Canal in Belgium, take-offs were scheduled for 0600hrs.

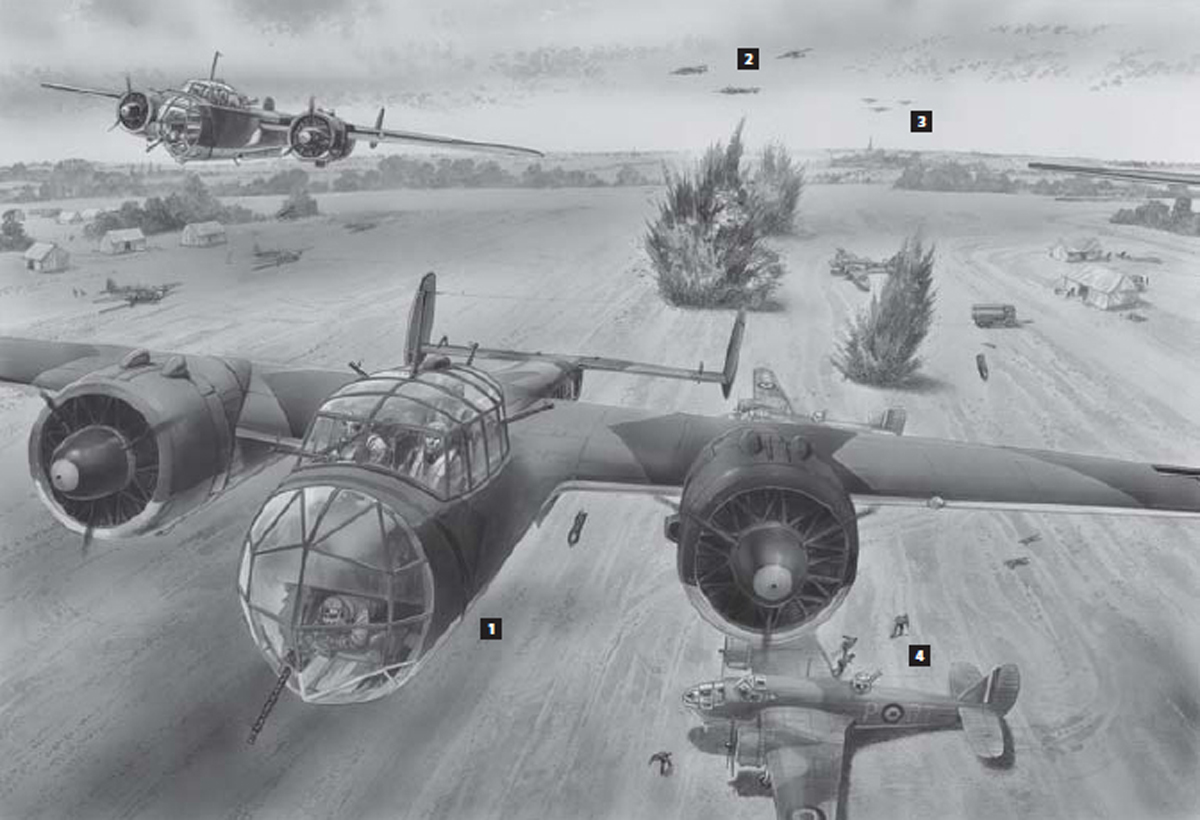

At 0545hrs, Oberleutnant Reimers, flying Do 17Z-2 U5+LM (1), approached Condé-Vraux at church-steeple height, achieving complete surprise. Reimers and his two wingmen each released ten 50kg fragmentation bombs, followed by six other bombers. The second Kette (2) followed about 20 seconds behind the leaders, offset to one side to attack the Blenheims not targeted by the leaders. The third Kette (3) followed 20 seconds later, hitting the squadron fuel dump. The entire attack lasted 45 seconds.

The RAF ground crewmen dived for cover as the Dorniers crossed the airfield boundary, roaring in at low-level and high speed. The small bombs erupted amongst the parked Blenheims (4), blowing up one after another. The attack was so sudden that the base’s anti-aircraft gunners had no time to react, a solitary Vickers .303in. machine gun opening fire as the last Dornier egressed to the east.

Six Blenheims were destroyed in the attack. The remaining five were all damaged to some extent and, when 114 Squadron evacuated the Condé-Vraux seven days later, they were all abandoned. No RAF aircrews were lost and only two ground crewmen were slightly wounded in the surprise attack.

Consistent with their doctrine, the Luftwaffe launched the offensive with massive bombing strikes against Armée de l’Air and AASF airfields. The Do 17Zs approached at low level, frequently taking their targets by surprise. (Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-342-0603-25)

While the German airborne assaults on ‘Fortress Holland’ and the Belgian Fort Eben Emael took the spotlight, in southern Belgium the Luftwaffe also attempted an air-delivered special operation – called ‘NiWi’ – to seize the crossroads at Nives and Witry that controlled the Panzers’ routes into France. Some 98 Fieseler Fi 156 ‘Storch’ light liaison aircraft attempted to deliver two companies from III. Bataillon/Infanterie-Regiment Großdeutschland (III./IRGD) while three Junkers Ju 52/3m transports provided airborne resupply.

However, morning fog caused the whole affair to go awry with the assault force being scattered throughout the countryside – 16 Fi 156s and one Ju 52/3m were lost – and the only effect was that they cut numerous telephone lines. All this did was prevent two companies of the bicycle-mounted Belgian Chasseurs Ardennais from receiving their orders to withdraw.

Meanwhile, overhead the Panzer columns Oberst Gerd von Massow’s Jafü 3 Messerschmitts flew standing patrols, shooting down one (a Po 63-11 of GR I/22) of the 11 AdA reconnaissance aircraft that Général François d’Astier sent roaming across Belgium and Luxembourg. The others reported the German Army’s presence in alarming strength around Maastricht as well as discovering two large, long motorized columns snaking across the Luxembourg countryside. By 0930hrs, the latter reports began arriving at FACNE HQ and Têtu requested permission to strike the armoured columns but Georges, who regarded them as a feint, forbade attacks near towns or villages due to fear of civilian casualties.

Although largely caught on the ground, ZOAN lost only one fighter group in the Luftwaffe’s initial airfield attacks, the AdA launched 363 defensive fighter sorties, shooting down 40 Luftflotte 3 bombers, during the first day’s battles. (Private collection)

Battle P2200 ‘GB•K’ was shot down by flak on the first day of battle while attacking motorized columns advancing through Luxembourg and crash-landed at Clémency where all three crewmen were captured. (Thomas Laemlein)

More aggressive and less inhibited by collateral damage concerns, Air Marshal Arthur Barratt, commanding the British Air Forces in France (BAFF), authorized AASF commander Air Vice Marshal P. H. L. Playfair to mount interdiction strikes that afternoon. Four unescorted formations of eight Battles each attacked through vicious anti-aircraft fire from the two motorized regiments of I. Flak-Brigade, losing 13 aircraft shot down. Even bombing from heights as low as 250ft, they caused negligible damage.

In the first day of battle, the Luftwaffe lost 88 twin-engine bombers,3 plus many others were damaged or developed mechanical problems, so for the next four days the daily operations tempo fell to between 800 and 1,000 sorties, largely attacking lines of communications to a depth of 50 miles beyond the Meuse, trying to keep Georges’s reserve units from getting to the front. Nevertheless, Luftflotte 3’s disappointing first day’s results required its Do 17Zs and He 111s to continue attacking French airfields, 23 of which were struck on 11 May and 11 more the day after.

The extra efforts finally began to take effect, destroying eight of the AASF’s Blenheims and another half dozen Battles on the ground, as well as 31 French bombers and 68 AdA fighters, during the next four days. Damage to French airfields and the destruction of aircraft – coupled with Vuillemin’s overall force-conservation strategy (he expected a protracted defensive campaign during which exposure to losses should be minimized) restricted most units to one mission per day – limited the Allied air defence to an average of 434 AdA and 160 RAF fighter sorties each day.

Against these 600 sorties, the Jagdwaffe’s daily average of 1,500 sorties was overwhelming and proved instrumental in wresting the all-important aerial superiority from the Allies. Destroying 147 enemy fighters for the loss of 80 Messerschmitts during this critical period, the Jagdflieger forced their opponents to increasingly defend the airspace over their own bases, well behind their lines.

Meanwhile in the north, Heeresgruppe B’s successes during the first three days forced the AdA, AASF, and Belgian air forces to launch 74 bomber sorties against the captured Belgian bridges spanning the Maas. Thirty-three of these were shot down. Additionally, on the third day, once General der Kavallerie Erich Hoepner’s XVI AK (mot.) Panzers were sighted advancing across the Belgian plain, ZOAN sent its Groupement de Bombardement d’Assaut 18 (GBA I and II/54), with 18 new, fast Breguet 693 twin-engine assault aircraft, to attack them. Ten were blasted from the sky by the Panzers’ accompanying motorized flak batteries.

The twin effects of these dramatic and alarming losses caused Vuillemin and Playfair (now down to 72 serviceable bombers) to abandon daylight attacks, except under the most dire circumstances. For the Luftwaffe, once it was recognized that the bombing threat to the Ruhr was eliminated, additional Jagdgruppen were released from Reich air defence duties for combat over the front lines. The synthesis of these decisions resulted in even increased numbers of Messerschmitt fighters defending against the diminishing numbers of Allied bombers, resulting in disaster when they were again forced – by Guderian’s success at Sedan – to attack in broad daylight.

In the pre-dawn darkness (0535hrs), the first of 41,140 motorized vehicles belonging to Gruppe Kleist crossed the border and drove through the small, peaceful, and defenceless Duchy of Luxembourg. Four hours later, on Guderian’s central route of advance (called a ‘Rollbahn’ by the Panzertruppen), the leading elements of Generalleutnant Friedrich Kirchner’s (1. Panzer-Division) Kradschützen-Bataillon 1 (Kradsch-Bat. 1) motorcyclists and Aufklärungs-Abteilung (mot.) 4’s (Aufkl.-Abt. (mot.) 4) armoured cars, entered Martelange, Belgium. There they surprised and routed the 1er Régiment de Chasseurs Ardennais’s 4e Compagnie (4e Cie/1er ChA).

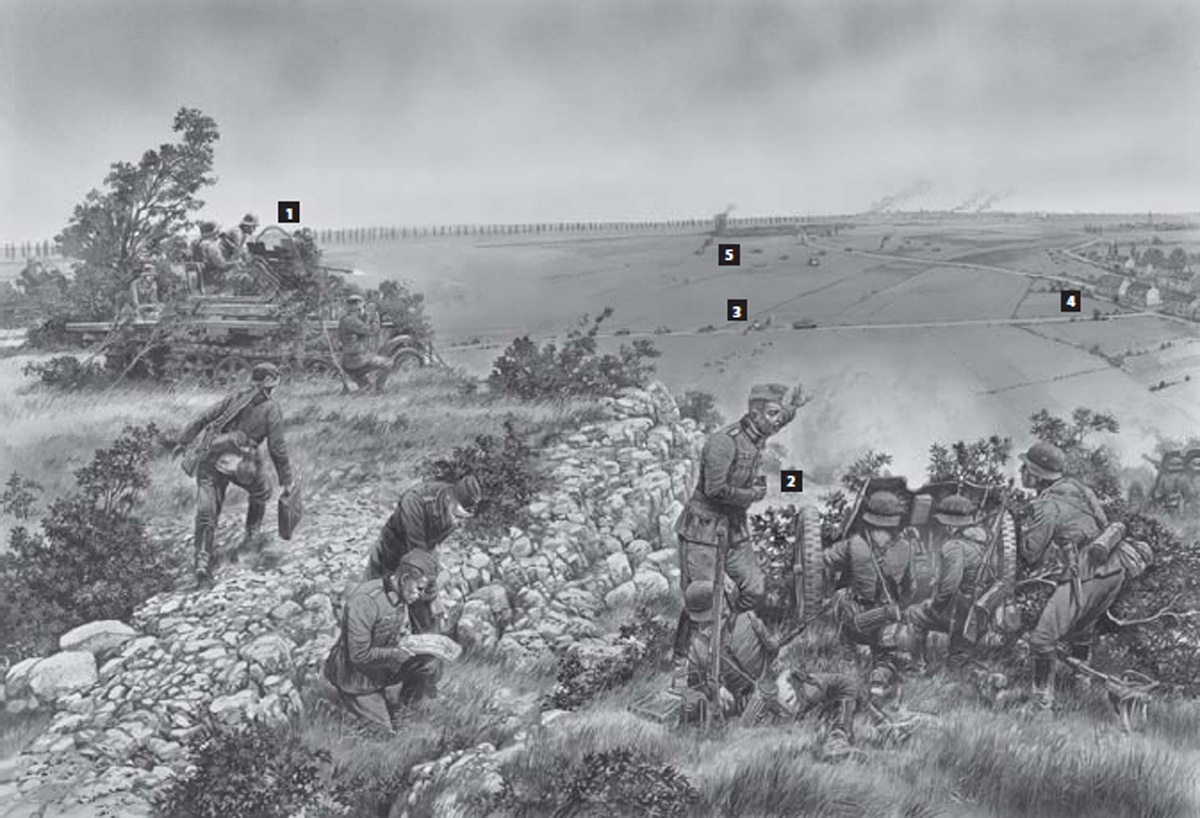

Continuing the advance through the Sûre River valley, the motorcycle battalion approached Bodange, where 5e Cie/1er ChA had fortified the small village. Dismounting – and expecting the same results – the motorcycle infantry attempted another hasty assault. With ‘Operation NiWi’ having intercepted the company’s orders to withdraw, the Belgians fought fiercely, repulsing the initial attacks through effective use of the terrain. After the third battalion of Kirchner’s Schützen Regiment (mot.) 1 (III./SR (mot.)) attacked, supported by their 7.5cm leIG 18 guns, the defenders finally surrendered at 1900hrs, having lost two of the company’s three officers killed in action.

Similarly, though not as dramatically, on the northern Rollbahn, Generalleutnant Rudolf Veiel’s 2. Panzer-Division was held up at Nives until II./SR (mot.) 2 cleared out the Chasseurs Ardennais and the road blocks they left behind as they withdrew towards Namur to join the Belgians’ main line of defence.

Guderian’s primary adversaries in the Ardennes were the horse-mounted cavalry and motorcycle-infantry of two French light cavalry divisions. The cavalry (note spurs on the trooper in background) and infantry included MAC 7.5mm FM 24/29 LMG teams, such as seen here. (Thomas Laemlein)

On the southern Rollbahn, at about 0900hrs Generalleutnant Ferdinand Schaal’s (10. Panzer-Division) Aufkl.-Abt. (mot.) 90 clashed with the two horse-mounted regiments of 2e DLC at Habay-la-Neuve, north-west of Arlon. When Sperrle’s Do 17P reconnaissance aircraft spotted the cavalry’s Hotchkiss light tanks, Panhard armoured cars, and lorried infantry driving northwards out of Mouzon, Longwy and Montmédy, it caused a major scare. Kleist ordered Schaal to wheel left and attack in strength. 10. Panzer-Division quickly mauled the lightly armed horse cavalry before the mechanized elements arrived, forcing Général Berniquet to abandon Arlon, withdrawing to the south behind the Semois River.

A PzKpfw IV Ausf. D command tank of 4./Pz.-Rgt. 1 in Belgium, 12 May 1940, knocked out by a French 25mm anti-tank round that destroyed its transmission. Repaired, it was in battle again south-east of Sedan two days later. (Thomas Laemlein)

By the end of the first day, Guderian was six hours behind schedule and Reinhardt’s XLI AK (mot.) was still in Germany. Kleist’s response was to order Veiel’s 2. Panzer-Division off the northern Rollbahn and allow the 6. Panzer, followed by the 2. Infanterie-Division (mot.), to move forward.

The next day, Kirchner’s reconnaissance elements encountered Huntziger’s 5e DLC, forming a 20-mile-wide screen of defensive positions with artillery support from Libramont to Rossignol. Before these hastily prepared defences, Kirchner deployed Panzer-Regiment 1 (Pz.-Rgt. 1) which, following a devastating Stuka bombardment, quickly drove through the cavalry’s positions and destroyed half their artillery (II/78e RATTT). Hard pressed, Général Chanoine withdrew his troopers to the Semois as well. This time Huntziger dispatched an infantry battalion (I/295e RI from Général Pierre Lafontaine’s 55e DI) to bolster the forward defence centred at Bouillon, and ordered it held ‘at all costs’.

Huntziger’s withdrawal of his cavalry to the south left Corap’s horse-mounted 3e Spahi Brigade alone in the Ardennes. When unit commander Colonel Olivier Marc learned this, he withdrew to the west, to the Meuse, creating the first crack between the 2e and 9e Armées. Without the Spahis covering his left flank, Chanoine’s reinforced cavalry holding Bouillon could easily be outflanked. That evening Kirchner’s Kradsch-Bat. 1 discovered this fact and overnight established a bridgehead to the west, at Mouzaive.

From the air Guderian’s 112-mile-long vehicle columns could not be missed. While his light motorized units ranged well ahead, the heavy mechanized units – Panzer regiments, combat engineers, corps artillery, and supply columns – soon became ensnarled in horrendous traffic jams, clogging the few roads allocated to them. When Generalmajor Werner Kempf’s 6. Panzer-Division finally crossed the Belgian frontier, angling onto Guderian’s right wing, as the 6. Panzer-Division’s war diary relates, ‘The division was forced apart during the advance by elements of the 2. Panzer-Division as well as the 16., 23., and 24. Infanterie-Divisionen [units of List’s III and VI AKs] which slipped in between [our formations]. In the afternoon and evening there was no longer any clear picture as to where the march movement groups and the individual formations were located.’

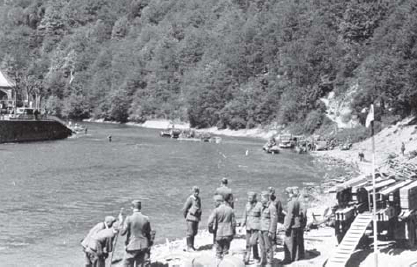

In the background vehicles of 1. Panzer-Division ford the small Semois River at Bouillon, Belgium, on 12 May 1940. Under sporadic and desultory French 155mm fire from Torcy, Guderian’s engineers (foreground) begin construction of a wooden trestle bridge. (NARA)

Assimilating the results from his Potez 637/63-11s roaming over southern Belgium, d’Astier reported to GQG, ‘reconnaissance shows that the enemy is making an important drive westward in the Ardennes. The columns are carrying pontoon bridging material. Large motorized and armoured forces are driving toward the Meuse at Dinant, Givet, and Bouillon, coming from Marche and Neufchâteau. One can therefore conclude that the enemy is carrying out a very serious movement toward the Meuse.’ Focused on the tank clash developing on the north Belgium plain, Gamelin, Georges, Billotte and the army commanders discounted the AdA’s reports, believing that they only indicated a feint.

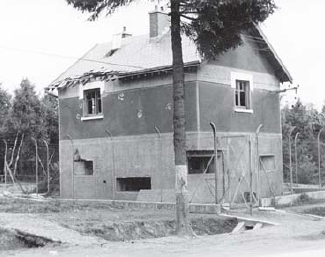

Along the French-Belgian border the French constructed eight maisons fortes (blockhouses camouflaged as houses) mounting machine guns and anti-tank guns and manned by the 15e Compagnie, 147e RIF. MF13 (seen here) on the road from Bouillon to Sedan delayed elements of the 10. Panzer-Division for two hours before being overcome. (M. Romanych)

Before dawn the next morning, at Mouzaive Kirchner’s Kradsch-Bat. 1 – followed by a battalion of Panzers (II./Pz.-Rgt. 2) – outflanked Chanoine’s cavalry line along the Semois. Threatened in the rear, when attacked by SR (mot.) 1, the defenders at Bouillon crumbled. The infantry battalion, a group of ‘fat and flabby men in their thirties’ with ‘slack discipline’ and weak NCOs, scattered and ‘only 300 demoralized men were seen again, crying “treachery” against the cavalry and devoid of any value for the actions the following day’.

The defenders had blown the town’s bridges but the Semois was merely a meandering trout stream and Pz.-Rgt. 1’s tanks were soon fording the river at several points while the combat engineers of Pionier-Bataillon (mot.) 37 (Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 37) constructed a new bridge. Learning that the Semois line had been broken, Georges gave 2e Armée first priority for Allied air support, but Huntziger failed to order any sorties.

On his own initiative d’Astier requested 50 sorties from the AASF to bomb Neufchâteau and Bouillon that evening. Playfair’s command, heavily committed in northern Belgium, could muster only 15 aircraft from four squadrons. They failed to hit anything meaningful and another six Battles were shot down by German flak.

At Cugnon, Schaal’s Aufkl.-Abt. (mot.) 90, followed by the riflemen of Schützen Brigade (mot.) 10 (SB (mot.) 10), assaulted French positions on foot, turning Chanoine’s other flank and allowing the 10. Panzer-Division to cross the Semois as well. While Huntziger ordered Chanoine’s cavalry to defend from the line of eight maisons fortes (‘fortified houses’), one on each road leading into the Sedan sector, the two Panzer divisions soon ejected the 2e DLC once again and that afternoon converged on the city. By nightfall their leading elements occupied portions of the northern bank of the Meuse.

MF10, on the road from Mouzaive to Floing and Sedan, delayed SR (mot.) 1 for over three hours, until II./Pz.-Rgt. 2’s Panzers arrived. Today the ruins stand as a memorial to Lt. Boulenger and his four-man crew who gave their lives in the battle. (Author’s collection)

Despite the fact that XIX AK (mot.) had advanced to the Meuse in three days, due to the chaotic, 155-mile-long traffic jams on the northern Rollbahn, Reinhardt’s two divisions had been seriously delayed and were confusingly intermixed with two of List’s infantry corps. Consequently, true to his threat, on 14 May Rundstedt decided to subordinate Gruppe Kleist to List’s AOK 12.

A PzKpfw II of 2. Panzer-Division driving through Sugny, Belgium, headed for Sedan, 13 May 1940. Having the furthest distance to travel, and the most traffic jams to negotiate, this unit did not arrive at Sedan until Guderian’s other two divisions had begun their cross-river assaults. (Thomas Laemlein)

On the French side of the Meuse, Georges finally reacted positively to the reports that Panzers were approaching Sedan. Anticipating the possibility of a breach in his ‘battle line’, he transferred Général Jean Flavigny’s 21e Corps d’Armée HQ from GQG reserve to Huntziger, assigning him the 3e Division Cuirassée (3e DCr) and 3e Division d’Infanterie Motorisée (3e DIM) to form his colmatage (‘plug’) behind Sedan.

For his part, Huntziger ordered the 71e DI from his reserve to Général de Corps Pierre-Paul-Charles Grandsard’s 10e Corps d’Armée to take position between the 55e DI and the 3e Division d’Infanterie Nord-Africaine (3e DINA). Additionally, Lafontaine ordered his reserve regiment (213e RI) forward, but allowed them to bivouac 6 miles short of their intended positions.

These movements began on the evening of 12 May, with orders for the units to be in place within two days. However, there was no sense of urgency because, at every echelon of command, the French generals were victims of what we now call ‘mirror imaging’. As Général Joseph Doumenc, commanding the GQG Reserve, wrote later, ‘Crediting the enemy with our own battle methods, we imagined that he would not attempt to cross the Meuse until he had brought up a considerable amount of artillery. The five or six days we thought he would need were to give us time to reinforce our own defences.’

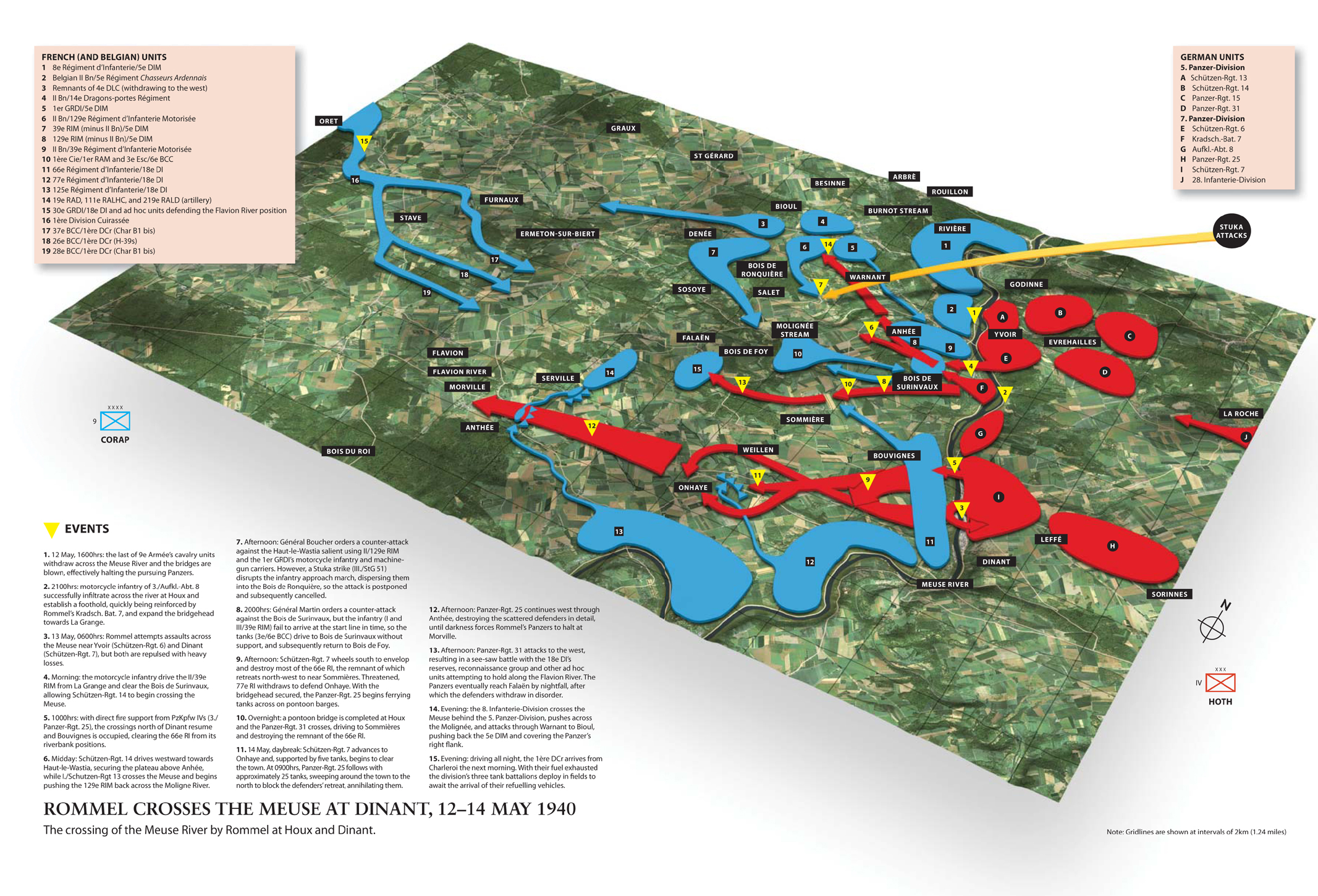

In the northern part of the Ardennes – between Namur, Belgium, and Givet, France – from opposite sides both armies were racing to the Meuse. After threading their way through the lengthy lines of infantrymen forming up at the frontier (General der Infanterie Adolf Strauß’s II AK), the leading elements of Hoth’s XV AK (mot.) – Rommel’s 7. Panzer-Division, with Generalleutnant Maximilian von Hartlieb genannt Walsporn’s 5. Panzer-Division following – crossed the border, skirted the Belgians’ initial demolitions by motoring off-road, and drove to Saint-Vith in three hours.

At this sleepy Belgian town, a special operations unit of the OKW Abwehr (3. Kompanie/Bau-Lehr-Bataillon zbV 800 ‘Brandenburg’4) captured three of the town’s four bridges intact, allowing Rommel to continue his advance unabated. Racing towards the Ourthe River, at dusk his Kradsch-Bat. 7 drove headlong into the 3e Cie/3e ChA’s prepared positions at Chabrehez. From fieldworks well sited amidst the undulating countryside, the Belgians put up a ferocious defence and by the time Rommel could deploy his heavy units, darkness had fallen, leaving him 12 miles short of the day’s objective.

Like Guderian’s and Reinhardt’s Panzers, Rommel – seen here riding in his staff car – had little difficulty driving through the impassable Ardennes. (NARA)

From the west, Général Corap’s two mixed cavalry divisions (1ère and 4e DLCs) crossed the Meuse, their mechanized elements (Hotchkiss tanks, Panhard armoured cars and motorcyclists) pushing on to the Ourthe, with the horse cavalry and lorried infantry following the next morning. Behind them 9e Armée infantry were not nearly so expeditious. Caught by surprise, Général Julien Martin’s 11e Corps had most of its 22e DI on exercises in the rear area and had to reorganize before beginning their march. The 18e DI had to travel 55 miles from their bivouac in France to their positions opposite Dinant, so Général Duffet sent two battalions (one each from the 66e and 77e RI) ahead by lorry, and planned to arrive at the Meuse with the rest of his division in four days.

The next morning Rommel’s heavy units smashed through the 3e Cie/3e ChA at Chabrehez and at about 1345hrs his Aufkl.-Abt. 37 arrived at the Ourthe to find the French 4e DLC on the other side, blowing up one bridge after another. However, once the bridges were destroyed, Général Paul Barbe withdrew his cavalry to Marche. With no defensive fire covering the demolitions, Rommel’s Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 58 easily threw pontoon bridges across the river and Aufkl.-Abt. 37’s armoured cars rushed forward, followed quickly by his PzKpfw 38(t) tanks (Pz.-Rgt. 25). Surprised by Rommel’s sudden and savage onslaught, Barbe’s cavalry and infantry companies scattered. His dozen Hotchkiss H-35/-39 light tanks (4e RAM) attempted a counter-attack which, badly outnumbered and heavily out-gunned, was immediately crushed, and the shattered division fled into the forests in disorder.

The delays at Chabrehez and the Ourthe had the benefit of allowing Walsporn’s Aufkl.-Abt. 8 and Pz.-Rgt. 31 to join Rommel, and Hoth attached these units to the 7. Panzer-Division for the final push to the Meuse. Organizing two ‘pursuit detachments’, Rommel sent them off through the hills, firing liberally – but blindly – into the forests on both sides to scare off the scattered French cavalry. ‘Gefechtsgruppe Bismarck’ (Oberst Georg von Bismarck with his SR (mot.) 7 and II./Pz.-Rgt. 25) descended into Dinant mid-afternoon on 12 May, while ‘Gefechtsgruppe Rothenburg’ (Oberst Karl Rothenburg with his Pz.-Rgt. 25(-) and SR (mot.) 6) arrived at Yvoir, 5 miles to the north, a short time later.

At his HQ in Vervins, Corap was alarmed by the dual harbingers of an aerial reconnaissance report describing an enemy motorized column 15 miles in length approaching Marche and the precipitate collapse of his cavalry screen. In response he ordered the 1ère and 4e DLCs to withdraw behind the Meuse and for all the bridges, from Dinant to the Bar River, to be blown. Additionally, he ordered Général Jean Bouffet (2e Corps commander) to detach one battalion from his 5e DIM (II/39e RIM) and send it to the 11e Corps to cover the gap between Yvoir and Dinant. Corap also assigned the withdrawing 1ère DLC to Martin, who distributed it amongst his infantry, dispersing its combat power to man defensive positions along the riverbank. Martin also hurried four more of his own battalions to Dinant. The exhausted infantrymen, plus some divisional artillery, arrived about 1600hrs that afternoon, just as Rommel’s motorized forces lined the opposite bank of the river, looking intently for a way across.

Opposing Rommel’s river crossing at Dinant were French infantry, whose machine guns, such as the 8mm Hotchkiss Modèle 14 (M1914), proved very effective in thwarting the initial attempts. (Thomas Laemlein)

Between Yvoir and Dinant, at Houx Aufkl.-Abt. 8 found an undefended crossing point: an ancient weir connected to a long wooded island to which, on the far side, was attached a lock-gate for transiting river traffic. The French unit assigned to cover this sector (II/39e RIM) failed to occupy its riverbank positions in time, deploying instead on the wooded high ground – Bois de Surinvaux – overlooking the Anhée basin. About midnight Rommel’s motorcycle troops threaded their way across the weir, island and lock to establish a bridgehead on the opposite shore.

Following early morning raids by two Kampfgeschwadern of Do 17Zs (KGs 76 and 77) at Dinant, Rommel’s assaults across the Meuse began with shelling by his Artillerie-Regiment 78 (AR (mot.) 78). Beneath the barrage his combat engineers (Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 58) and riflemen (SR (mot.) 7) began crossing the 250ft-wide river in rubber boats. From the rocks and houses along the riverbank the French 66e RI fought back tenaciously, machine-gunning and mortaring the approaching boats. Only a few troops made it to the opposite shore and, as Rommel recorded, ‘The crossing had now come to a complete standstill, with the officers badly shaken by the casualties their men had suffered. On the opposite bank we could see several men [who were] already across, among them many wounded.’

The French machine-gun nests were well concealed and Rommel’s artillery was unable to target them so he brought up some PzKpfw IIIs and IVs and a pair of howitzers to take the enemy defences under direct fire, silencing enough of them to resume the crossings at 1100hrs. By midday SR (mot.) 7 occupied Bouvignes and, moving from one position to another, slowly eliminated the French riverbank resistance. The battered remnant of the 66e RI withdrew to Sommières allowing Rommel’s riflemen to establish a secure bridgehead about 3 miles deep.

Hidden by the early morning mist the motorcycle troops at Houx expanded their bridgehead, but once the fog cleared, the French (II/39e RI) began a determined resistance, initially halting all further reinforcement until the Germans’ repeated assaults dispersed them. Once the French infantry were driven off, three battalions of Walsporn’s SB (mot.) 5 crossed the river and began attacking Boucher’s 129e RIM at Anhée. Soon afterwards, pioneers rigged a cable ferry using the 8-ton bridging pontoons as boats, bringing across armoured cars, anti-tank guns and other heavy weapons that afternoon.

In addition to his PzKpfw IIIs and IVs, Rommel ordered a pair of leFH18 10.5cm howitzers brought down to the riverbank to fire directly into the enemy machine gun emplacements on the opposite shore. Note that the third span of the bridge has been dropped into the river by Belgian demolition teams. (NARA)

Boucher organized a counter-attack against the bridgehead’s northern flank at Haut-le-Wastia, ordering his reserve battalion (II/129e RIM) to support a score of machine-gun armed Renault AMR-33 tankettes (4e Esc/14e RDP/4e DLC) and eight Schneider P-16 half-track armoured cars from his divisional reconnaissance group (1er GRDI). However, a strike by two dozen Stukas (III./StG 51) shattered the infantry on their approach march and it was 2100hrs before the counter-attack could be organized again. By that time, due to darkness Boucher’s artillery (11e RAD and 211e RALD) could no longer provide fire support, so the attack was postponed to the next morning, when it was repulsed by eight Panzers from Pz.-Rgt. 31.

The village of Bouvignes under fire by Rommel’s artillery and tanks – as seen through his own Leica camera – as his pioneers and riflemen cross the Meuse and eliminate the French defenders (out of view to the left). (NARA)

Martin also organized a counter-attack, planning on hitting Rommel’s riflemen in Bois de Surinvaux at 1930hrs, using two infantry battalions (I and III/39e RI) to support a squadron of 15 Renault R-35 light tanks (3e/6e BCC). The tanks were accompanied by nine Renault AMRs from the 1ère DLC and supported by a 10-minute barrage by Martin’s three artillery groups (19e RAD, 219e RALD, and 111e RALHC). A half hour late, the French armour attacked, driving to the forest, where they captured seven motorcyclists but encountered no significant enemy forces. Even with the delay the French infantry failed to arrive in time to accompany the tanks and, unable to hold the terrain they’d cleared, the Renaults withdrew.

The AdA provided an aerial counter-attack that afternoon with seven LeO 451s (GB I and II/12) bombing the crowded columns of vehicles backed up on the road between Dinant and Sorinne. Covered by 27 Bloch MB 152s (GC I/1 and I/8), the raiders arrived successfully, but bombed ineffectually, and returned safely with only three bombers damaged by Rommel’s flak batteries (Flak-Abts (mot.) 59 and 86).

There were no French ripostes against the southern bridgehead and Rommel’s engineers used their larger 16-ton bridging pontoons to build barges, ferrying some 30 tanks to Bouvignes overnight. Early the next morning Bismarck’s SR (mot.) 7 advanced 3 miles to Onhaye followed closely by Rothenburg’s Pz.-Rgt. 25. The advancing Panzers were taken under fire by French artillery and anti-tank guns on the flanks, which knocked out several and damaged more, including Rothenburg’s tank and Rommel’s command/signals vehicle, slightly wounding both. By nightfall, however, Rommel’s Panzers had advanced to Morville, clearing enough room west of Dinant for his entire division to assemble and continue the advance the next day.

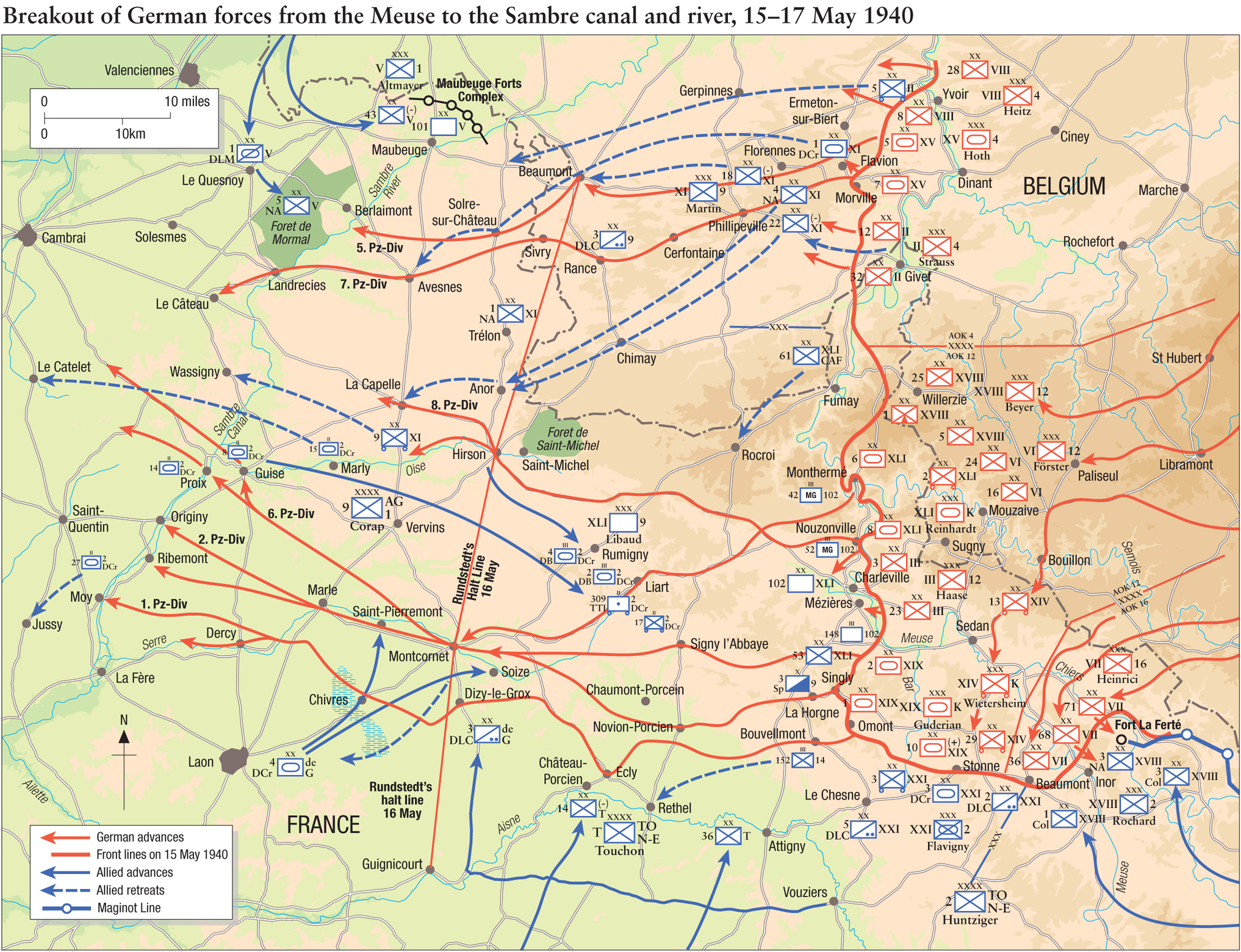

During the two-day battle Général Duffet’s 18e DI, a reservist unit, had been decimated. The 66e RI was overrun and destroyed, the 77e RI ‘appeared to have fled’, and the 125e RI fell back in disorder. Reacting to Martin’s defeat, Corap rushed the 4e DINA from its reserve position at Trilon, on the French frontier, to Florennes, and Georges redirected the 1ère DCr to Flavion from the GQG reserve, to plug the gap.

Back at the Houx bridgehead, Walsporn’s 5. Panzer-Division also regrouped, taking position on Rommel’s right wing, the two Panzer divisions now poised for a major thrust towards Philippeville. Meanwhile Strauß’s II AK and Heitz’s VIII AK mopped up French resistance on both banks of the Meuse north and south of the crossing.

When the sun arose off the right flank of 2e Armée on 13 May, it found Huntziger’s units off-balance, malpositioned and unprepared to meet the horrendous assault about to be unleashed upon them. Général Lafontaine’s 55e DI was shuffling its forward companies to the west, building a ‘defence in depth’ behind Colonel Pinaud’s 147e RIF, which manned the blockhouses and pillboxes in this sector. This allowed Général Baudet’s 71e DI to move into positions south-east of Sedan. However, the elderly and ailing Baudet was tardy in beginning his unit’s movements and marched his men 37 miles overnight; the morning found them ‘weary and unsettled in their new position’.

As they were moving to their new positions, many of the 55e DI elements were caught in the open when the Luftwaffe appeared overhead at 1000hrs and ‘therefore took refuge in the woods for the day, meaning to rejoin their units on the following night’. Additionally, Lafontaine’s reserve regiment (213e RI) was still 6 miles from its assigned positions, leaving the division’s ‘Ligne Principale de Résistance’ stretching from Frénois to Wadelincourt unsupported.

Even with the infantry disorganization – which was expected to be resolved by the end of the day – Lafontaine initially remained confident, primarily because he was now assigned most of the corps artillery (110e RALCH), an additional four dozen 155CS heavy guns. This provided Lafontaine with 104 ‘tubes’.5 Next door, Baudet had 48 guns (38e RAMD), a dozen of which could also cover the southern portion of Lafontaine’s front.

Guderian, with his aide Oberstleutnant Riebel, watching his engineers complete rebuilding the bridge at Bouillon, 12 May 1940. (NARA)

While the defenders seemed to have plenty of artillery, tragically, neither of the two French reserve divisions, and none of the fortress troops, had any anti-aircraft guns whatsoever. Instead, they were expected to use their infantry machine guns to defend themselves against the Stuka attacks to come. As Gamelin later stated, ‘by placing medium and light machine guns on the slopes [of La Marfée] behind the left bank [south side of the river], it was possible to prevent Stukas from diving into the valley’. Lacking even a basic understanding of air power, he could not have been more wrong.

Facing this disorganized defence, across the river Guderian’s troops had regrouped overnight and were systematically deploying in preparation for their afternoon assault. The main attack would be in the centre, crossing the river just north of the city, executed by XIX AK’s Sturmpionieren (StPion.-Bat. (mot.) 43), Kirchner’s riflemen (SR (mot.) 1), and the elite Infanterie-Regiment Großdeutschland (IRGD). Following the central assault, the flanks would be covered by the time-phased crossings of 10. Panzer-Division to the east and 2. Panzer-Division to the west.

Standing on the bridge in front of where Guderian was standing in the preceding photo, looking above the buildings in that photo’s background, even today one sees the Hotel Panorama, where Guderian based his HQ on the evening of 11/12 May 1940. (Author’s collection)

Supporting the main attack Guderian concentrated most of his artillery – his corps artillery (AR (mot.) 49), Kirchner’s regiment (AR (mot.) 73) and the heavy battalions from the other two divisions (III./AR (mot.) 74 and 90); altogether he had 96 ‘tubes’. However, since these units had only their ready ammunition with them, 50 rounds per battery, they would not begin their heavy barrages until after the Luftwaffe completed its ‘preparation of the battlefield’.

Aerial bombardment was provided by Generalleutnant Bruno Loerzer’s II Fliegerkorps, augmented by StG 77 from Richthofen’s VIII Fliegerkorps, just transferred from supporting Heeresgruppe B in northern Belgium. Following morning harassing attacks by small formations of Do 17Zs, at midday the first wave of 90 Stukas arrived in Gruppe strength and began pounding the French artillery emplacements.

The Stukas were followed by Loerzer’s Dorniers, flying 310 sorties total, bombing the French riverside positions (KG 2) and routes of march (KG 3), isolating the front-line troops from possible reinforcements. Then the Stukas returned, completing 180 sorties, dive-bombing individual casemates along the riverbank, shattering the defenders’ nerves with their screaming dives, whistling bombs and crashing concussions.

The defending French fighters (primarily GC I/5) were distracted by similar attacks supporting Reinhardt’s XLI AK (mot.) assaults across the Meuse at Monthermé, consequently out of nearly 500 sorties the only loss was a single Stuka (3./StG 76) hit by ground fire and crash-landing near Bouillon. With no Allied fighter opposition to counter, Massow’s Messerschmitts went ‘down on the deck’, strafing French troops attempting to move to the front and attacking their field HQs with 20mm cannon, shooting off their command post radio antennas, further isolating the front-line defenders.

As the last Stukas left the battlefield, Guderian’s 96 guns unleashed a 50-minute barrage pinning down French front-line troops, cutting off reinforcements and silencing the surviving French artillery. Additionally, Guderian brought up the 102. Flak-Regiment’s heavy battalion – 36 8.8cm Flak 36/37s firing in the horizontal mode – and some PzKpfw IVs to take the surviving French casemates under direct fire. Aiming at the gun embrasures in a technique called ‘posting’ – as if pushing a letter into a mailbox slot – these weapons were augmented by IRGD’s six mechanized 7.5cm Sturmgeschütz (StuG) III assault guns (StuG-Bty (mot.) 640).

At 1600hrs, as the noise, smoke and dust dissipated, four battalions of combat engineers (StPion.-Bat. (mot.) 43, Pion.-Btls 37, 41 and 49) dragged their heavy kapok rafts from concealed positions among the riverside buildings down to the banks, launched and loaded them, and began crossing the 65-yard-wide river. Though dazed by the bombardments, the surviving French fortress troops immediately manned their weapons, sweeping the water’s surface with a maelstrom of machine-gun fire.

Luftflotte 3’s Stuka group was reinforced with Richthofen’s StG 77 for the assault at Sedan. Ju 87Bs flew 180 dive-bombing sorties against French bunkers, artillery emplacements, communications centres and field HQs, effectively neutralizing and paralyzing some defenders before the first of Guderian’s pioneers placed their rafts into the river. (André Wilderdijk)

At Bazeilles, flanking fire from Baudet’s heavy artillery (IV/38e RAMD, near Douzy) helped the I/147e RIF successfully repulse SR (mot.) 69’s attempted crossing, destroying 81 of 96 rafts. Downstream, at Wadelincourt, the men of SR (mot.) 86 were slow getting their rafts to the water’s edge, the defenders (II/147e RIF) – fighting from three blockhouses and 12 pillboxes – recovered from the bombardments and their vicious firestorm drove the assault teams back behind cover.

On the southern end of the nearly 2-mile-wide front of 1. Panzer-Division’s assault there were only two pillboxes facing the attackers and from these positions II./IRGD weathered a hail of bullets that wiped out three of StPion.-Bat. (mot.) 43’s assault squads before two companies (6. and 7./IRGD) of riflemen could get to the other side and begin eliminating the defenders. Opposite Kirchner’s northern wing, Lafontaine’s reservists – 6e Compagnie/295e RI manning open earthworks – were totally devastated by the pre-assault bombardments and fled at the first sight of the Germans’ river crossing. Lacking the strength, training, discipline, leadership and fortified positions needed to meet the enemy’s onslaught they abandoned their positions, making the crossing by Kirchner’s II./SR (mot.) 1 and Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 37 seem, as Guderian later observed, ‘as though it were being carried out on manoeuvres’.

On the right flank, Kradsch.-Bat. 1 and I./SR (mot.) 1 crossed onto the undefended ‘Iges peninsula’, a northern loop of the Meuse severed at its base by a canal. They quickly got across the canal against dwindling resistance and joined the rest of SR (mot.) 1 just in time for the aggressive commander, Oberstleutnant Hermann Balck, to launch a powerful assault on Lafontaine’s ‘Ligne Principale de Résistance’. This string of eight pillboxes and a blockhouse – many of them unfinished and some unarmed – stretched from Frénois to Wadelincourt. However, because the 213e RI had failed to take its positions supporting this line, Balck’s riflemen overran the nine scattered casemates by sunset.

From Casemate 104 ‘Paquis de Cailles’, an FCR Type A4 blockhouse, and others III/147e RIF repulsed the initial cross-river assaults by 2. Panzer-Division. Note the scaffolding on the left (evidence of lack of completion) and the effects of direct fire (‘posting’). (M. Romanych)

At this point the French defence crumbled. Overwhelmed, Lafontaine’s reservists broke and ran, allowing Balck’s riflemen to advance into a virtual vacuum. By midnight his four battalions had expanded the bridgehead to 5 miles deep, reaching Chéhéry after brushing aside a single battalion (III/295e RI) hurriedly deployed along La Marfée heights. This advance relieved the pressure on IRGD, allowing III. Bataillon to cross south of Sedan, followed by I./SR (mot.) 86 establishing a small foothold at Wadelincourt after nightfall.

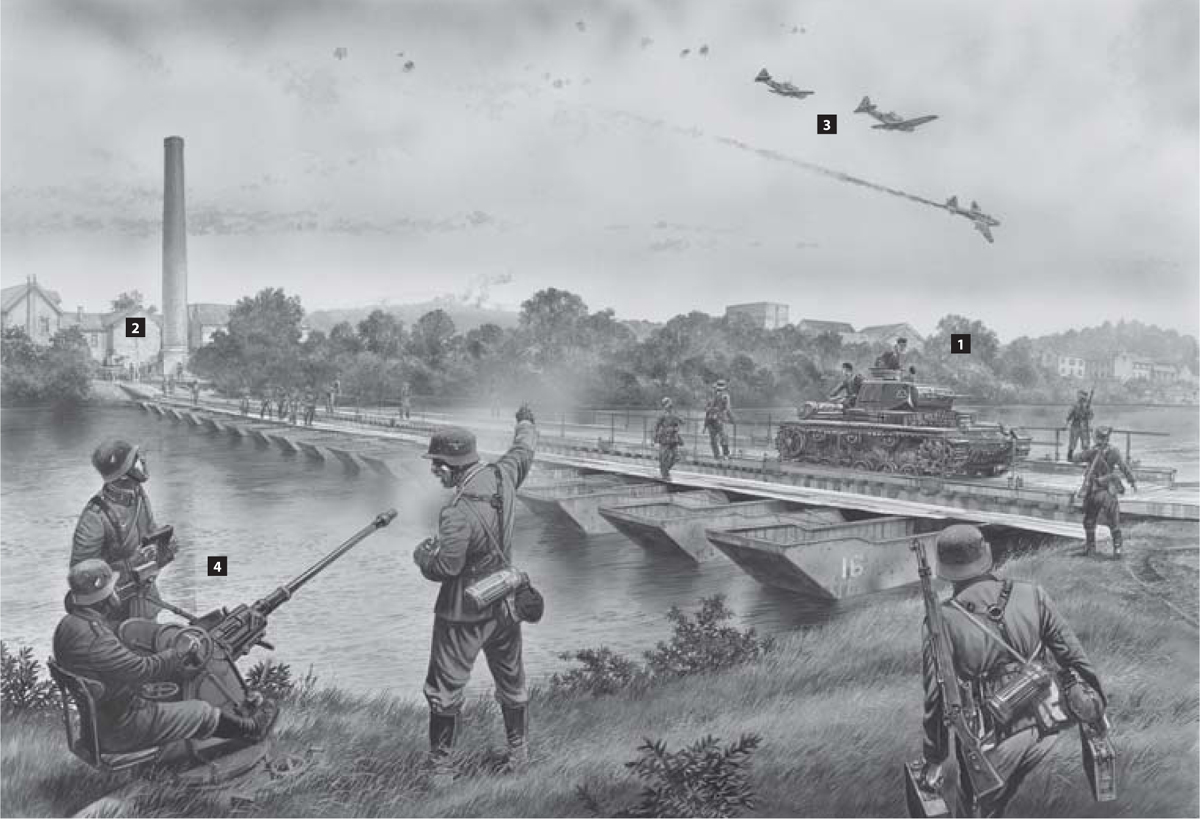

At 0100hrs on 14 May, 1. Guderian’s Pioneer-Bataillon (mot.) 505 completed constructing a 16-tonne Brückengerät B across the Meuse River, connecting the villages of Gaulier and Glaire. At midday, with 2. Panzer-Division’s Pioneer-Bataillon (mot.) 38 still working to finish their own pontoon bridge at Vrigne-Meuse, Guderian ordered that division to send its Panzers and self-propelled anti-tank guns across the Meuse using the Gaulier–Glaire bridge.

Seen here is the last PzKpfw III Ausf. E tank (1) of Panzer-Regiment 3’s 4. Kompanie crossing the bridge while the first Panzerjäger I of Panzerjäger-Abteilung (mot.) 38 waits its turn to cross (2). Tank number ‘435’ was the fifth tank of 4. Kompanie’s 3rd platoon, as its number coding indicates. The yellow unit marking –including 2. Panzer-Division’s ‘two-dot’ symbol – and white ‘K’ for ‘Gruppe Kleist’ are carried on the upper glacis of the hull, while the yellow triangle stencil on the turret indicates the 3rd Platoon.

Realizing the danger, the AdA and AASF mounted a maximum effort to destroy the bridges. After an initial misdirected effort by ten RAF Battles – the two morning raids attacked bridges upstream from Sedan, well inside friendly lines – the French launched mid-morning strikes by Bre 693 assault aircraft, followed by modern LeO 451 and ancient Am 143M bombers at midday. These attacked the 10. Panzer-Division’s pontoon bridge at Wadelincourt and the mechanized columns queued up to cross it. In the mid-afternoon the AASF sent 45 Battles and eight Blenheims also against pontoon bridges east of Sedan and the vehicles queuing up for them, followed by 29 Blenheims from Bomber Command that attacked troop concentrations and vehicle columns from Givonne to Bouillon. The Gaulier–Glaire bridge was not attacked all day.

However, flying to attack the eastern bridges and vehicle columns, the RAF bombers frequently overflew the Gaulier–Glaire bridge – such as the ‘vic’ of three Fairey Battles (3) shown here – en route to their targets. Guderian’s bridges were defended by the respective Panzer division’s attached Luftwaffe flak battalions, such as the two 2.0cm FlaK 30s (4) seen here from Flak-Abteilung (mot.) 83, as well as elements of the corps-level 102. Flak-Regiment (mot). The Luftwaffe anti-aircraft guns shot down 19 Battles, while defending Messerschmitts destroyed another 11 Battles and 13 Blenheims. An additional ten Battles were so badly damaged they were abandoned on their airfields during the ensuing retreat.

Built along identical lines was Casemate 107 ‘Longues-Orgières’, between Pont-Maugis and Remilly-Aillicourt, from which machine-gunners and an anti-tank gun crew helped repulse 10. Panzer-Division’s initial cross-river assaults upstream from Sedan. (Author’s collection)

Meanwhile Veiel’s 2. Panzer-Division – which had to drive the ‘long way round’ through Sugny, Belgium, to get to their ‘jumping off point’ – finally arrived on Guderian’s right flank at Donchery as the other divisions’ assaults began. Without waiting for a preparatory artillery bombardment, two pioneer companies (Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 38) and two battalions of riflemen (SR (mot.) 2) began crossing at 1730hrs. Attacking in the face of withering fire from three blockhouses, an artillery casement and eight pillboxes, they were repulsed. Once Balck’s riflemen had advanced through Frenois, the assault engineers of 3./StPion.-Bat. (mot.) 43, specially trained in attacking bunkers, rolled up the east flank of the defenders (III/147e RIF) by eliminating Artillery Casemate 47 and its two 75mm guns, and the large Blockhouse 46. After sunset Veiel’s riflemen crossed the river and advanced through Lafontaine’s secondary line, vacated by the panicked I/331e RI, securing the heights of Croix-Piot.

At his command post in a wooded ravine a mile south of Bulson, by 2000hrs Lafontaine’s confidence had evaporated and he began organizing a counter-attack. However, by this time a fully-fledged fiasco was unfolding. The commander of SF Montmédy’s I/169e RAP (supporting I/147e RIF against 10. Panzer-Division), positioned north-east of Bulson, reported shell explosions on the eastern slope of La Marfée heights, suggesting they might be from Panzers. As this information was passed upstream, the shell explosions became ‘muzzle flashes’ of Panzer cannon, and ‘they were approaching’! The word spread to Lafontaine’s gunners (45e RAMD) and once Colonel Poncelet, commanding 110e RALH, made the premature decision to retreat, artillerymen from both units piled into lorries and fled their batteries, shouting ‘Panzers at Bulson!’ to everyone they encountered. The developing defeat now became a rout.

Meanwhile, with the Meuse secured from Donchery to Wadelincourt, Guderian’s engineers (Pion.-Bat. 505) immediately set to work building pontoon bridges. The first, connecting Gaulier and Glaire, was completed early the next morning and Kirchner’s Panzers began crossing the river at 0720hrs. He quickly sent them south to take the Bulson Ridge, the next high ground beyond La Marfée heights.

Général Pierre Lafontaine’s 55e DI HQ was located in a bombproof bunker built into the rocky wall of a heavily wooded ravine south of Bulson, known as Fond-Dagot. With some effort, it can be located today. (Author’s collection)

Thirty minutes later an Hs 126 observation aircraft from Kirchner’s aviation squadron (2.(H)/23 (Pz)) spotted two columns of French tanks advancing from Chémery – one due north along the Bar River valley and the other angling north-east towards Bulson (a third was converging on Bulson, unseen, from the south). This was Lafontaine’s long-awaited counter-attack – three companies of small, slow-moving FCM-36 infantry-support tanks (7e BCC), each leading a battalion from 213e RI – also ordered to secure Bulson Ridge. Being faster,6 six PzKpfw IIs and eight PzKpfw IIIs of 4./Pz.-Rgt. 2 arrived at Bulson first, but after crossing the ridge they ran headlong into approaching 1er/7e BCC and a short-range firefight erupted, the 13 FCM’s 37mm guns destroying two Panzers outright and soon disabling all but one of the others.

Kirchner ‘fed the fight’ sending three more Panzer companies directly into battle as they came off the Gaulier bridge. Two of these drove straight to Bulson and, joined by the advance units of IRGD, mounted a coordinated counter-attack that drove both French columns from the ridge, only ten FCM-36s (mostly 2e/7e BCC) surviving the battle.

The next company (8./Pz.-Rgt. 2) was sent towards Connage where a pair of 3.7cm Pak 36 anti-tank guns had initially halted the approaching FCM tanks (3e/7e BCC). Aided by a pair of half-track-mounted 8.8cm guns (Zgkw 18t of schwere PzJäg.-Abt. (mot.) 8) the arriving Panzers destroyed the French tanks by shooting into their more vulnerable sides, while the two companies from StPion.-Bat. (mot.) 43 drove the infantry (II/213e RI) back into Chémery.

In the centre IRGD continued its advance southwards, capturing Villers and Maisoncelle, where they found 40 abandoned artillery pieces. By 1300hrs Lafontaine’s last line of defence was overrun and the shattered remnants of his division withdrew southwards to Roucourt Bois to join Flavigny’s 21e Corps. Guderian had lost only 120 men killed and 400 wounded in the two-day battle.

After the 3e DCr and 3e DIM arrived at Le Chesne that morning Huntziger ordered Flavigny to ‘contain the bottom of the [enemy] pocket’ by deploying around Bois de Mont-Dieu and ‘having contained the enemy, counter-attack as soon as possible in the direction of Maisoncelle–Bulson-Sedan’. Despite the fact he commanded one of France’s most powerful mobile formations, Flavigny was assigned a defence-first mission – so, passing on the opportunity to mount an immediate armoured counter-attack, he obediently dispersed his armoured division into small static packets to await the approaching Panzers.

The next morning the pontoon bridge at Gaulier was completed, allowing the Panzers to cross to join the battle. Here a kleine Panzerbefehlswagen armoured ambulance (SdKfz 265, modified from a PzKpfw I) passes a motorcycle courier and a group of French POWs to join a PzKpfw II and III on the far side of the river. (Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1978-062-24)

Meanwhile, another bridge had been completed overnight at Wadelincourt, allowing 10. Panzer-Division to move its heavy vehicles towards the battlefront, and a third bridge went up north-west of Remilly-Aillicourt. Belatedly realizing the danger to his far right flank, Groupe d’Armées 1 commander, Général Gaston Billotte, ordered a ‘maximum effort’ by the AdA and AASF, telling d’Astier, ‘victory or defeat will depend on those bridges’.

Following an initial misdirected effort by ten RAF Battles, the morning’s first raid against Guderian’s bridges was flown by nine Bre 693 assault aircraft (GBA I and II/54). Escorted by 15 Hurricanes (73 Sqn) and 15 Bloch MB 152s (GC I/8), the attackers ingressed without interference and surprised the flak batteries – but their bombing proved ineffective.

This raid was followed by a midday strike by 11 Am 143Ms (GBs I and II/34 and II/38) and five LeO 451s (GB I and II/12). The faster, modern LeO 451s led the way, attacking 10. Panzer-Division columns stretching through Bazeilles, losing one bomber to flak. The lumbering, obsolete Am 143Ms followed, escorted by a dozen MS 406s (GC III/7) with twelve MB 152s (GC I/8) and nine new Dewoitine 520s (GC I/3) sweeping ahead. The fighters held off Massow’s Messerschmitts but 102. Flak-Rgt’s 135 vehicle-mounted 3.7cm and 2cm anti-aircraft guns shot down five of the old bombers.

The Allies’ main effort was mid-afternoon when Playfair’s AASF sent 63 Battles and eight Blenheims against the two eastern pontoon bridges and the mechanized columns queuing up for them. Escorting Hurricanes (1 Sqn) shot down five Bf 109Es (I./JG 53) without loss, and the bombers accounted for three more of the defending fighters, but the Messerschmitts destroyed at least 11 Battles and five Blenheims. The bombers that made it to their targets braved a maelstrom of flak and another 19 Battles were blasted from the sky. A follow-up raid by 29 Blenheims from Bomber Command (21, 107, and 110 Sqns) lost eight aircraft to the ever-present Bf 109Es while attacking troop concentrations and vehicle columns (29. Inf-Div(mot.)) from Givonne to Bouillon.

The target: long lines of vehicles crowding the roads from Bouillon to Sedan. Mostly these were the support units of the 10. Panzer-Division and Guderian’s corps supply column (seen here). Note the ‘K’ on the trucks’ windscreens, designating these as ‘Gruppe Kleist’ vehicles and authorizing priority on the Ardennes roads, and the half-track-mounted 3.7cm Flak gun in the background, guarding them. (NARA)

The attackers: although patently obsolete and initially relegated to night bombing, even the ancient Amiot 143Ms were thrown into the fray, attempting to halt the Panzers crossing the Meuse at Sedan. Of the 11 bombers attacking, five were lost to flak. (Private collection)

The effort was a disaster for the RAF – the highest losses of any day in the service’s history thus far. None of the bridges were touched and 2. Panzer-Division followed Kirchner’s tanks across the Gaulier bridge while its Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 38 constructed another one at Vrigne-Meuse. By sunset over 600 Panzers were on the west side of the Meuse.

With his lines of communication across the Meuse secure and his opponent reeling southwards, at 1400hrs Guderian made the decision upon which the entire Fall Gelb campaign turned: he ordered Kirchner to wheel west and advance as rapidly as possible across the Bar River and Ardennes Canal. The II./SR (mot.) 1 had already captured an intact bridge at Omicourt and repelled several feeble attacks from Marc’s Spahis, and after Balck regrouped there, at 1500hrs he struck out to the west, his III./SR (mot.) 1 driving 6 miles to Signy by midnight.

In this decisive battle, Lafontaine’s 55e DI had been destroyed and Baudet’s 71e DI had deserted, the only surviving element (205e RI) being reassigned to the 3e DINA. At the end of 15 May, the 10e Corps and both divisions were deleted from the French Army’s order of battle. That same day, Generalleutnant Gotthard Heinrici’s VII AK (AOK 16) arrived at the Chiers River east of Sedan, prompting Huntziger to withdraw his 3e DINA and 138e RIF further to the south-east, evacuating 130 casemates along the river and fatally exposing Fort La Ferté at the eastern end of the Maginot Line.

The only armour available to Huntziger’s 2e Armée at Sedan, at least until the arrival of the 3e DCr, were 90 FCM-36 light tanks. These small, two-man infantry tanks mounted a 37mm gun but proved vulnerable to flanking fire, especially through the side-mounted radiators. (Alain Alvarez)

There would be more battles at the Sedan bridgehead, with IRGD and 10. Panzer-Division fending off numerous attacks by Flavigny’s 21e Corps – the cauldron battle at Stonne being the best known – but Fall Gelb’s Panzer breakout had begun.

At midnight on 12/13 May, as Rommel’s motorcyclists crossed the weir at Houx and Guderian’s staff planned the next day’s assault at Sedan, 6. Panzer-Division arrived on the Meuse at Monthermé. Reinhardt’s Panzers had made surprising progress, especially considering that the first vehicle of Generalmajor Werner Kempf’s division had not crossed the Luxembourg border until 0600hrs that morning!

At Monthermé the Meuse cuts through the Ardennes ridge via a deep gorge and Kempf’s reconnaissance troops (Aufkl.-Abt. (mot.) 57) and riflemen (SR (mot.) 4) found the heavily wooded terrain rugged and steep. The only road bridge over the river had been properly ‘blown’ leaving only twisted half-submerged trusses jutting from the water. The Monthermé sector was defended by the 42e Demi-Brigade de Mitrailleurs Coloniaux (DBMC), a regiment-size unit of Malagasy and Vietnamese machine gun companies. Part of Général Portzert’s first-rate 102e Division d’Infanterie de Forteresse (DIF), they were dug into well-prepared positions and finished casemates overlooking strategic points along the west bank.

With Kempf’s artillery (AR (mot.) 76) still ensnarled in the traffic jams to the east, the Luftwaffe provided support, II Fliegerkorps diverting some 360 bomber and 90 Stuka sorties from the Sedan bombardment that day. Despite the air attacks the first attempted crossing, upstream from the destroyed bridge, was repulsed with heavy losses.

However, Kempf’s engineers (Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 57) soon discovered that the twisted metal of the destroyed bridge was snagging the empty rafts as they floated downstream and, once some PzKpfw IIIs and IVs blasted the casemates covering the mangled wreckage, they were able to string the rafts together into a rickety footbridge. After dusk riflemen began crossing and by midnight had established a small, tenuous bridgehead. The next morning Portzert’s artillery (160e RAP) smashed the footbridge, isolating the battalion-size bridgehead and ending Kempf’s progress for the day.

South of Kempf’s bridgehead, General der Artillerie Curt Haase’s III AK arrived at Nouzonville and the 3. Infanterie-Division began its assaults across the river. The 52e DBMC fought back stubbornly from well-hidden and well-sited positions, repulsing the first two crossing attempts, but once Stukas pounded the defenders into submission, a third assault succeeded late in the day.

Balck’s motorized infantry, near Omont, await the command to resume the advance on 15 May. Once Guderian wheeled Kirchner’s 1. Panzer-Division westwards and crossed the Bar River, the Panzer breakout had begun. (NARA)

To the north, at Givet – between Kempf’s and Rommel’s bridgeheads – the French 22e DI was under the command of its chief of staff, the commander, Général Hassler, having been injured in a car accident. Witnessing the destruction of the 18e DI on his left at Dinant, the ‘acting commander’ ordered his regiments to withdraw 6 miles to the west, falling back at the first sight of Strauß’s approaching infantry.

Général Martin, whose 11e Corps had been battered by Rommel’s assaults, attempted to salvage the situation by forming a defensive line south of Florennes. Having just received the 4e DINA, he ordered the commander, Général Charles Sancelme, to establish a blocking position astride the road to Phillipeville, with the remnant of 18e DI on his left and the 22e DI on the right.

However, with his army unravelling before him, Corap decided to withdraw en masse 15½ miles to prepared positions lining the French frontier, and he duly informed Billotte. The Groupe d’Armées 1 commander agreed but recommended an intermediate stop-line between Charleroi and Rethel. With three different defensive lines now proposed by the French commanders, orders to the retreating units became hopelessly confused. With communications broken by movement and spotty receipt of orders, the elements of three divisions became scattered between Martin’s blocking position and the French frontier.

Into this chaos was sent France’s premier armoured formation, the 1ère DCr. Initially moved to Charleroi, Billotte held this division in reserve awaiting the outcome of the clash in the Gembloux Gap. Realizing, too late, the magnitude of the disaster at Dinant, he assigned it to Corap early on 14 May ‘to clear the Dinant pocket as from today’. That afternoon Corap transferred the 1ère DCr to Martin, who ordered Général Marie-Germain Bruneau to assemble his division north-east of Florennes to ‘attack in the Dinant direction as soon as possible’.

Travelling 23 miles overnight along bomb-blasted and refugee-clogged roads, three battalions of Bruneau’s tanks (25e BCC lost its way) arrived at the assembly area between Ermeton-sur-Biert and Flavion early on 15 May. They were followed by the motorized infantry and artillery, and lastly the fuel and supply columns. Because of the excruciatingly slow pace, the 65 Char B1 bis and 40 Hotchkiss H-39 tanks used all their fuel and had to await their bowsers before attacking.

After pausing overnight to regroup, that morning Rommel’s 7. Panzer-Division headed for Phillipeville, leading with Pz.-Rgt. 25. Bruneau’s 28e BCC stranded tank crews spotted the Panzers passing only 2 miles to the south and the Char B1s opened fire, disabling several before Rothenburg rerouted his tanks through a wood further south. Avoiding a head-to-head engagement, Rommel brought his artillery (AR (mot.) 78) to bear on the stationary Stahlkolossen destroying all save seven before he had safely bypassed the enemy armour.

Following Guderian through the Ardennes, Reinhardt’s units became entangled in horrendous traffic jams, slowing their progress to the Meuse and delaying supporting units such as artillery. (NARA)

Trailing Rommel in right echelon, Walsporn’s Pz.-Rgt. 37 smashed Bruneau’s 26e BCC (H-39s) and 37e BCC (Chars). Late in the day, Bruneau ordered his tank battalions to withdraw to Beaumont, but only 14 Chars and 20 H-39s were able to do so. Meanwhile Rommel’s Panzers overran the scattered elements of the 4e DINA, rolled through Phillipeville at midday, and drove 6 miles beyond, piercing both Martin’s blocking position and Billotte’s intermediate stop-line.

While Corap’s decision to withdraw made sense for Martin’s defeated 11e Corps, it spelt disaster for General Libaud’s neighbouring 41e Corps d’Armée de Forteresse (CAF). At Monthermé the 42e DBMC dutifully evacuated most of its fortifications just before Kempf’s SR (mot.) 4 renewed its attacks, now accompanied by flamethrowers and a tremendous artillery barrage (AR (mot.) 76). By 0830hrs the reserve lines and rearguard were overrun, with the unit commander captured. A pontoon bridge was quickly thrown across the Meuse, and soon Pz.-Rgt. 11 broke out into open country.

At Nouzonville the 52e DBMC also withdrew, allowing Haase’s III AK to build two pontoon bridges, permitting Generalleutnant Adolf-Friedrich Kuntzen’s 8. Panzer-Division to join the pursuit. Since French fortress units lacked motor transport, Reinhardt’s two Panzer divisions quickly rounded up the straggling elements of the 102e DIF. Of the division’s 9,926 fortress troops, only 1,200 escaped – Général Portzert was not one of them.

North of Monthermé the 61e DI also retired as ordered. Being a reservist unit it had little organic motor transport and this was parked well to the rear, forcing the infantrymen to retreat on foot. They were quickly overhauled by Reinhardt’s Panzers; only 700–800 men made it to Billotte’s intermediate stop-line. By the end of the day, Libaud’s 41e CAF was completely overrun, creating a vacuum ahead of XLI AK (mot.).

Into this empty void stumbled Général Albert Bruché’s 2e DCr. This hapless armoured formation, initially sent to Charleroi on 14 May to back up Blanchard’s 1ère Armée, was diverted to join Corap’s 9e Armée, its tanks travelling by rail, all others by road. There, Bruché was told that his now scattered division was to go to Signy-l’Abbaye, at the south end of Billotte’s intermediate stop-line, and that his unit was now assigned to Army Detachment Touchon.

Général Robert-Auguste Touchon, a decorated Great War hero commanding the small 7e Armée near the Swiss border, was ordered to establish a force linking Corap’s and Huntziger’s armies, answerable directly to Georges’s TONE HQ. He was assigned the nearly non-existent 41e CAF, the 14e and 36e DIs arriving from the south, Marc’s 3e Spahis, and the 2e DCr.

Bruché’s tanks were shipped to Hirson, where they detrained and headed cross-country, more or less falling into column with his motorized infantry, tractor-drawn artillery and supply columns driving from Guise. Through this large, irregular stream of vehicles, men and units – spread across some 25 miles – Kempf’s Gefechtsgruppe Esebeck7 slashed like a sabre late that afternoon. Smashing through Bruché’s artillery (309e RATTT), destroying two of its three battalions, the Panzers clashed with the leading battalion of Char B1 bis tanks. Totally surprised, the French scattered, their tanks reeling west and north, spreading themselves widely between Hirson and Saint-Quentin, while others escaped to the south. Bruché tried to regroup at Rethel, but found he had only two companies of motorized infantry, one company of H-39s, four Char Bs and a battery of artillery. Meanwhile Kempf arrived at Montcornet by midnight.

Rommel’s Skoda PzKpfw 38(t) Panzers on the attack. (Thomas Laemlein)

French prisoners being escorted back to Givet. The speed of the German motorized forces overwhelmed the French infantry as they attempted to retreat to their frontier defences resulting in over 50,000 prisoners being collected in three days. (NARA)

To the south Guderian was anxious to make similar progress but was stymied by the last vestiges of French resistance. 1. Panzer-Division’s SR (mot.) 1 led the way but Kirchner’s right wing quickly clashed with Marc’s 3e Spahi Brigade, which tenaciously defended La Horgne. Fighting all day, the horse cavalry was eventually destroyed, suffering 629 casualties, with both regiment commanders being killed and Marc captured.

At Bouvellemont, Kirchner’s left wing encountered the 152e RI, the leading element of Général de Lattre de Tassigny’s just-arriving 14e DI. This unit also fought determinedly, checking the Germans’ advance but losing one third of its men. By nightfall it was forced to retire towards Rethel, where another defence was being organized.

At this point Kleist would have preferred to consolidate the bridgehead and build a defence along the southern perimeter, but after a heated discussion, he granted Guderian his freedom of movement. Leaving 10. Panzer-Division and IRGD behind with Wietersheim’s XIV AK (mot.) to defend the south flank at Stonne and, bypassing Rethel the next day, Guderian surged westward with his other two Panzer divisions. They drove 40 miles into open French countryside, dispersing the 3e DLC (sent from 3e Armée to join Général Charles de Gaulle’s group forming near Laon) joining Kempf at Montcornet.

Early on 16 May, at Bastogne Heeresgruppe A HQ learned that Kempf’s pursuit detachment had reached Montcornet during the night. Seeing that the southern edge of the Panzer thrust stretched some 55 miles from Stonne to Montcornet, with only the 12-mile front around Stonne defended, Rundstedt ordered all units to halt at the Beaumont–Hirson–Montcornet–Guignicourt line, except advanced units which were permitted to continue a maximum of 30 miles to the Oise to seize bridgeheads between Guise and La Fère, but an advance beyond the Oise would not be permitted until 18 May. The southern flank ‘was to be covered as the armies closed up [with] AOK 12 to be brought forward with all speed [to make] the southern flank more secure from French attack’.

Once clear of the French frontier defences, three of Kleist’s Panzer divisions roared across the open countryside, brushing aside small scattered French units as they drove 75 miles from the Meuse to the Oise River in just two days. (Thomas Laemlein)

That evening, OKH commander-in-chief Brauchitsch – who had the same apprehension – was relieved to learn of Rundstedt’s decision to halt the Panzers. He fully and immediately endorsed Heeresgruppe A’s Haltbefehl (halt order).

Earlier that day Guderian met Kempf in the marketplace at Montcornet. Since Kleist’s delineation of corps boundaries only went to Rundstedt’s Haltlinie (stop line), Guderian took charge, sending Kempf towards Guise, Veiel to Originy, and Kirchner to Ribemont and Moy to secure crossings over the Oise River. Blatantly disregarding his superiors’ instructions, he ordered the three divisions – not just advance units – to drive ‘until the last drop of petrol was used up’.

Along the Oise, Général Georges spread the scattered tank companies of the 2e DCr at numerous crossing points. These small bouchons (corks) were leaderless – Bruché’s command post was moving from Rethel to Guiscard – and totally lacked artillery and infantry support. Attacking forcefully at 1900hrs, unsurprisingly Kempf’s Panzers ousted the four companies (8e BCC and 14e BCC) deployed at Guise and Proix, destroying two of them; by the morning of 17 May he had secured two bridgeheads across the Oise.

Back at Bastogne, Rundstedt became increasingly anxious about his extended southern flank, ‘especially in the Laon area. This southern flank is just an invitation for an enemy attack.’ For that reason he further ordered that the Oise and Sambre rivers were to not be passed without his authorization. Rundstedt, the staunchly conservative Heeresgruppe commander who was still steeped in the methodical ways of World War I, had been just as surprised as his French adversaries by Guderian’s spectacular success at Sedan. He considered it a ‘miracle which [he] could not understand’.

Hitler, too, was visibly agitated over the apparent vulnerability of the extended Panzer thrust and, not placated by Brauchitsch’s explanations, travelled to Bastogne on midday of the 17th to see for himself. There, he too was relieved to learn of Rundstedt’s decision and, fortified with this knowledge, returned to Felsennest (his campaign HQ, a bunker complex in the Münstereifel Forest, south of Bonn), to rant against the OKH for not ‘building up as quickly as possible a new flanking position to the south … and ordered [Brauchitsch and Halder] peremptorily to adopt the necessary measures at once’.

When 9e Armée reported ‘about 100 [enemy] tanks have reached Montecornet’, d’Astier launched 26 LeO 451s (GB I and II/12 and I/31) against them. To avoid high losses the bombers attacked singly or in pairs over a five-hour period, dispersing their effort over time and space and, therefore, failed to do more than briefly delay the Panzers’ westward drive. (Private collection)

Meanwhile, unaware of their leaders’ mounting fears, Veiel’s 2. Panzer-Division struck at Origny, destroying another company (3e/8e BCC) of Char B1 bis. By the time Kirchner’s two pursuit groups arrived at Ribemont (Gefechtsgruppe Kruger – Oberst Walter Kruger with his SB (mot.) 1(-) and Pz.-Rgt. 2) and Moy (Gefechtsgruppe Nedtwig – Oberstleutnant Johannes Nedtwig with his Pz.-Rgt. 1(+)) at 0900hrs. Bruché’s three surviving companies withdrew their H-39s to the south-west.

One of several ‘corks’ used to stopper the bridges along the Oise River, at Guise the ten Char B1 bis tanks the 8e BCC’s 3e Compagnie (2e DCr) could not halt Kempf’s Pz.-Rgt. 11. Char 260, ‘Ouragan’, was immobilized by the failure of its Naeder steering system, with its right-hand tracks blown apart for good measure. (Antoine Misner)

Angry that Guderian had exceeded his remit, at 0700hrs Kleist ordered an immediate halt and flew to Guderian’s HQ at Soize (just east of Montcornet) to personally enforce it. During a violent reprimand, Kleist accused Guderian of disobeying orders. This altercation caused a crisis of command during which Guderian resigned, recalled Veiel by radio to have him take charge of XIX AK (mot.) and informed Rundstedt of his resignation. The Heeresgruppe commander immediately ordered List to go to Soize and defuse the matter.

That afternoon List informed Guderian that he was to remain in command and that the ‘order to halt the advance came from OKH [referring to Brauchitsch’s endorsement] and therefore must be obeyed’. With Rundstedt’s approval, List fashioned a compromise whereby Guderian was allowed a reconnaissance in force to the west but had to keep his HQ at Soize.

Guderian, typically, ordered his units – now once again including Schaal’s 10. Panzer-Division and the IRGD – to continue westwards that evening. Dutifully leaving his HQ at Soize, he followed with his advanced HQ, laying miles of telephone wire so that the Wehrmacht’s wireless intercept units could not monitor his communications or learn his location.

On the north side of the Panzer salient Rommel now had a new adversary. Général Henri Honoré Giraud was the energetic and aggressive commander of 7e Armée, which he had led into southern Holland – the ‘Breda extension’ of the Dyle Plan – but had been rebuffed by the 9. Panzer-Division. Subsequently, his army was split up: 16e Corps augmenting the Belgian Army at the Scheldt Estuary and his mobile units sent south to help stem the onrushing steel tsunami of Panzers.

At 0500hrs on 15 May, Billotte telephoned Georges asking to have Giraud replace Corap as commander of 9e Armée, saying, ‘It is essential to put some life into this wavering army. Général Giraud, whose vigour is well known, appears to me to be best fitted to take on this difficult task and able to effect the necessary re-invigoration.’

Georges, who was beginning to take a more active role in coordinating the defence, approved the move, firing Corap. He also transferred Huntziger’s 2e Armée to his direct control, and once Giraud was in place, did the same with the decimated 9e Armée. With these moves, Georges took charge of the defence against the rapidly advancing Panzers.

Arriving at Vervins late that afternoon, Giraud received situation briefings and afterwards, at 2030hrs, reported to GQG, ‘The 4e DINA appears to have some units west of Philippeville. The 18e and 22e Divisions … are completely disorganized. The 61e Division has abandoned Rocroi… I have ordered Général Martin to take charge of the defence line within our frontiers. My impression is grave.’

‘Our most ardent commander’ – highly respected, Général Henri Giraud was the natural choice to take over the disintegrating 9e Armée. But he was not a miracle worker – his command lasted only three days. (Getty Images)

The next evening (16 May), Giraud and Touchon received special orders from Georges: ‘You must first clear the area between the Oise and the Aisne … by an operation based on mechanised transport. Then [Touchon] must follow up this clearing operation by attempting a breakthrough north of the Aisne at Attigny–Rethel–Château Porcien.’

To mount the clearing operation, from the north Giraud sent what was left of Bruneau’s 1ère DCr to the Avesnes–La Capelle area to prepare for attacks against the northern flank of Guderian’s salient. Of the 50 tanks Bruneau had gathered at Beaumont, only 17 were not immobilized by mechanical breakdowns or fuel exhaustion. Passing through Avesnes, they blundered unexpectedly into Rommel’s Panzers.

Meanwhile, Rommel had overrun the 1ère DLC at Rance, capturing its motorcycle infantry battalion in a surprise encounter, then penetrated the thin frontier fortifications south of Solre-le-Château in a classic, well-coordinated combined arms assault. Driving relentlessly, Pz.-Rgt. 25 arrived in Avesnes about midnight, just as Bruneau’s tanks rumbled into town from the north-east.

As Rommel stated:

There must have been a battalion [25e BCC] of tanks [which] made good use of the gap [between I. and II. Bataillons] in the Panzer Regiment, and French heavy tanks soon closed the road through town. II. Bataillon at once tried to overcome the enemy blocking the road, but their attempt failed with the loss of several tanks. The fighting grew steadily heavier … and lasted until about 0400hrs. Dawn was slowly breaking when the battle was ended and contact was re-established with the II. Bataillon.

Only three French tanks survived the battle, retreating to Maubeuge.

Without pausing, Rommel drove through Landrecies, crossed the Sambre River and arrived at Le Câteau at 0615hrs the next day. The 7. Panzer-Division had advanced 50 miles in 48 hours, passing Rundstedt’s halt line because his command vehicle’s radio receiver had gone out, allowing him to transmit only.

Meanwhile, Walsporn’s 5. Panzer-Division, having decimated the 1ère DCr near Florennes, drove to Beaumont, where it destroyed the last of the 37e BCC and overran the remnant of Duffet’s 18e DI on 16 May. The next morning, crossing the Sambre at Berlaimont, the 5. Panzer-Division was stung by a counter-attack from elements of Général Picard’s 1ère Division Légère Mécanique (DLM; from Giraud’s disbanded 7e Armée), which had just arrived from northern Belgium. Attacking late in the day with ten Panhard AMD-35 armoured cars (6e Cuirassiers) and 15 S-35s (4e Cuirassiers), Picard’s effort lacked sufficient strength to destroy the Panzers’ bridgehead and they retired to Le Quesnoy at dusk with heavy losses.

On the south side of the Panzer salient, the only forces Touchon had available to execute Georges’s ordered breakthrough operation was an assortment of mechanized units hurriedly gathering at Laon. Christened the 4e DCr and assigned to de Gaulle, formerly the Commandant de Chars (tank operations officer) on the 5e Armée staff, it included two battalions of Char B1 bis, three battalions of Renault R-35s, a squadron of Somua S-35s, one company of the new, but notoriously unreliable Char D2 light tanks, and a motorized infantry brigade, plus reconnaissance, artillery, engineers and signals units.

Following the nighttime battle in Avesnes, the 25e BCC retired to the north. The next afternoon Rommel sent II./SR (mot.) 6 after them, and found these Hotchkiss tanks ‘formed up alongside the road, some of them with their engines running. Several drivers were taken prisoner still in their tanks.’ (Thomas Laemlein)

On paper the 4e DCr was the most powerful armoured unit in the French inventory, but as an ad hoc conglomeration of many geographically separated units it would take time to organize. Unlike most French commanders, de Gaulle was not going to wait – ‘I am going to attack tomorrow with whatever forces I have.’ His mission was to defend the Rethel–La Fère area against a possible Panzer thrust towards Paris and gain time for the new 6e Armée (formerly Army Detachment Touchon) to establish itself along the Aisne and Ailette rivers. To do so, the aggressive de Gaulle determined to secure bridgeheads on the Serre River at Saint-Pierremont and Montcornet, defend there and bombard the German columns (Gefechtsgruppe Kruger) moving westwards through Marle.

The next morning, 14 Char D2s (345e CACC), 36 Char B1s (46e BCC) and 90 R-35s (2e and 24e BCCs), together with a battalion of bus-borne infantry (4e BCP), gathered just east of Laon, and at daybreak they set out in two columns headed north-east. Crossing the Canal de Desschement at Chivres they overran a detachment from Gefechtsgruppe Nedtwig’s Aufkl.-Abt. (mot.) 4 and destroyed a 30-vehicle supply convoy, then the Char B1s and D2s angled towards Saint-Pierremont while the Renaults continued towards Montcornet.

French Renault R-35 tanks on the attack. (Thomas Laemlein)

At Saint-Pierremont, elements of Pion.-Bat. (mot.) 37 defended the bridges but the Chars battled their way across. About the same time as the trailing 4e BCP approached, one of Balck’s motorized infantry battalions arrived to retake the bridges and a desperate battle ensued. Lacking additional infantry, de Gaulle could not hold the bridgeheads and began withdrawing at 1700hrs, covered by a reconnaissance regiment’s (10e Cuirassiers) half-track armoured cars.

At Montcornet, 25 R-35s threatened Kirchner’s 1. Panzer-Division’s HQ, but were halted by more pioneers and some light flak guns (le Flak-Abt. (mot.) 83), and finally repulsed by a group of Panzers just coming out of the repair shops. The Renaults finally withdrew at 1900hrs, under heavy fire by six self-propelled 15cm sIG33 infantry guns of schwere Infanterie Geschütz Kompanie 702.