After a winter filled with a hundred different forms of semifrozen water, the first sighting of springtime bock beer is as welcome as the first crocus punching up through the remaining few inches of slowly melting black snow. This beer above all others is associated with spring. Rich, malty, and golden to ruby in color, bock beer is the crown jewel of the lager family — fortifying, sustaining, satisfying.

_2.jpg)

The story of bock beer begins with Crooked Waters, a tributary of the Ilm River, near the town of Einbeck, in central Germany. This water made the town one of the earliest international brewing centers, exporting beer as early as the eleventh century. By 1325 there was a warehouse full of Einbeck beer in Hamburg, the home base of the Hanseatic League, a trading organization that brought it to such distant ports as London, Russia, Norway, and even Jerusalem.

Early in the 1600s, a chronicler described Einbeck beer this way: “This delicious, palatable, subtle, extremely sound and wholesome beer, which because of its refreshing properties and pleasant taste is exported to far-away countries . . . all such Einbeck beer which shows the proper savor is a delicious famous, and very palatable beverage and excellent beer, wherewith a man, when partaken of in moderation, may save his health and sound senses, and yet feel jolly and stimulated.”

Another source gives a little more detail: “Of all summer beers, light and hoppy barley beers, the Einbeck beer is the most famed and deserves the preference. Each third grain to this beer is wheat; hence, too, it is of all barley beers the best.” Other sources add that the beer was pale and highly hopped.

Munich was a big customer, but by the mid-1500s it was starting to develop its own brewing reputation. The popularity of Einbeck beer may have stimulated Munich’s brewers to create their own version, and the story goes that the Einbeck name was corrupted to ein bock, not a very satisfying tale.

More interesting is the fact that the German word bock means “male goat,” as in the English word buck, referring to a male deer, goat, or other ungulate. This invokes the billy goat as a potent symbol of fertility, since ancient times symbolized by the astrological sign of Capricorn and firmly connected to spring, the season of rebirth. The leering goat faces on the labels and posters of old American bock beers bears out this connection. It may be just happy coincidence, but another thing the billy goat is known for is its kick, summing up the product it represents.

The mystique associated with bock beer lingers on in the old belief that somehow bock beer is made from the sludge removed from fermentation tanks during spring cleaning, which could never have been true. So, cut this out and carry it in your wallet:

NOTE: BOCK BEER IS NOT, NOR HAS IT EVER BEEN, MADE FROM THE GUNK AT THE BOTTOM OF THE BARRELS. IT IS A STRONG LAGER BEER MADE THE ORDINARY WAY, FROM MALT, HOPS, WATER, AND YEAST. THIS COMES FROM A VERY GOOD AUTHORITY, PRINTED IN AN ACTUAL BOOK.

Start your spring bock fling with a super-intense eisbock.

Then, as now, southern German tastes preferred a sweeter, less bitter beer, and the hoppiness of bock was accordingly reduced when it moved into Bavaria. Eventually laws were introduced that specified the strength of the wort (unfermented beer). Today, by law German bock must be at least 16° Plato (1.066 OG), with an alcohol content not less than 6.6% ABV.

The Paulaner brewery in Munich lays claim to a stronger version, called doppelbock. The former monastery was converted to a prison and the beer brand privatized around 1800. About that time, Paulaner named its strong bock beer Salvator (meaning “savior”). The term quickly became generic for similar beers, but around 1900, Paulaner began to defend its trademark, and other breweries changed their beers’ names but kept the -ator suffix, such as Imperator, Kulminator, Impulsator, and Celebrator. That tradition has been respected to the present day. By German law, doppelbock must be at least 18° Plato (1.072 OG).

You might start your spring bock fling in earliest March with a super-intense eisbock, a brew that is made by freezing the beer and removing some of the ice, thereby concentrating the alcohol and everything else. It’s thick, syrupy, and delicious. When Lent comes along, it’s time for fasting, but due to a loophole, somehow strong beer is not on the forbidden list, so a doppelbock can stand in for the forbidden foods. Or if you’re looking for something less heady, a regular old single bock will do.

As the season warms, the heavier beers give way to paler, drier types, and by May, when the beer gardens open, you’re on to the maibocks — golden in color, sweetly malty, but adequately balanced by classic noble hops, a sure sign that summer is right around the corner.

This is the legendary beer festival of Belgium, held in the university town of Leuven, long famous as a great drinking town and the traditional locus of the witbier style. It takes place during the last weekend of April.

This ad-hoc beer festival hosted by Three Floyds takes place the last weekend in April at a nondescript industrial park in northern Indiana, about an hour southeast of Chicago. It is mainly a release party and purchase opportunity for Dark Lord Imperial Stout, the most iconic among the current crop of highly sought-after collectors’ beers. After registering online and getting your tickets, then waiting to collect your allotment of rare Pokémon cards, er, I mean Dark Lord, you can get down to the real business of the event, which is participating in tasting circles, where a bottle of something rare and cool gains you entry to taste others like it with fellow devotees. Plenty of food, music, amusements, and some of the best people watching on the planet as long as you’re cool with the tipsy ’n’ tatted. Serious fun, except the waiting-in-line part.

While the legendary king of beer has been linked to several historical characters, sometimes with wildly entertaining stories, Gambrinus was pure sixteenth-century German fiction, misspelled from Gambrivius to the current form in a later Flemish translation. So we can’t really know when he was born, or where, but who cares? Sometimes it’s just enjoyable to engage in a beery group hallucination.

A springtime classic, lamb is a demanding dish, with its rich fattiness and slightly gamey flavors; grilling or roasting over wood ramps up the intensity even more. Lamb cooked like this demands a substantial beer with plenty of bitterness and/or roasty flavors to stand up to its intensity. If you’re not so much into lamb, these beers work equally well with a wood-fired steak or tri-tip roast.

Black IPA Also known as Cascadian dark ales, these are essentially IPAs colored a chestnut brown by the addition of a small amount of very dark malt, giving the crisp, dry palate and brisk hoppiness of an IPA with an overlay of a delicate espresso-like roastiness that provides a natural link to the carbonization on the surface of the lamb. Considerable bitterness in the beer slices through the fatty richness of the lamb.

Rauch Bock Rauch is simply the German word for “smoke,” indicating a beer that has been brewed from malt that was kilned over a wood fire, lending touches of ham or bacon smokiness to the beer. Such beers are a shocker at first, as these are flavors we don’t ordinarily experience together in a single sip, but once we are acclimated, they become ravishingly delicious. Normally based on the Märzen style, this rauchbier is the stronger bock version, which stands up well to the intensity of roast lamb and with just enough deep toastiness to make an additional flavor connection.

Imperial Red Ale Often brewed with rye these days, this style offers a rich caramelized raisin or burnt sugar character, with the wild citrus and spice signature of American hops connecting to the rosemary and thyme typically used to season the lamb. There is plenty of bitterness to counterbalance the rich, meaty flavors, but not so much roastiness that it overwhelms the pink meat’s delicate flavors.

Foreign Export Stout This is one of the stronger dry stouts, so named because its greater strength allowed it to be successfully exported from the British Isles in the days of the wooden ships. The sharp coffee-like character of the roasted barley echoes the flavor of the grill marks on the lamb, while the smooth, creamy texture and substantial bitterness cleanse the palate.

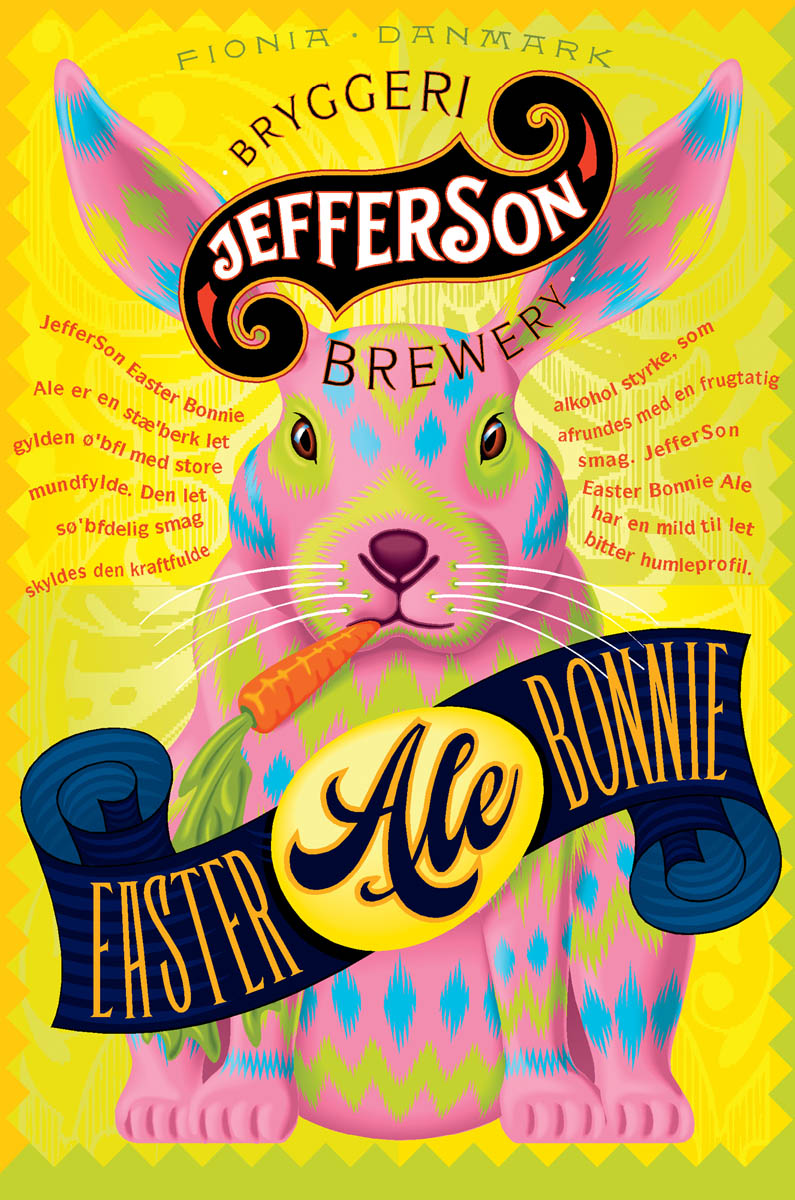

Every ancient pagan ritual and its Christian derivative should be an excuse for a dedicated beer style. The name of the Christian festival of Easter is derived from Eostre, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring. Sadly, the Easter beer tradition is a bit feeble these days, especially in the United States. Lager drinkers have their richly delicious bock beers, of course, and they serve the purpose and have plentiful pagan connections. There are also beers specifically labeled as Öster beers from Germany and Austria, often in the blond export mode, just shy of bock strength. Belgian brewers make celebratory beers for the season, but in typical Belgian manner there is nothing about them that could be considered a defined style — they’re just variants on the brewery’s house style. Het Anker makes a special version of Gouden Carolus with their fingerprints all over it: strong, sweetish, and a little spicy.

Scandinavia has the strongest tradition of special Easter beers, not surprising for a region draped in dark winter for much of the year, just itching for something to celebrate in early springtime. Around 1900, Scandinavian lager breweries started brewing their versions of doppelbock, which eventually were designated påskebryg (“Easter brew”) or forårsbryg (“spring brew”). Many modern versions continue in that tradition. But now we’re living in a crafty world, so the style has fractured into a variety of strongish beers, sometimes lagers but more often ales ranging from hazy gold to deep reddish amber. Several are briskly hoppy, like Mikkeller’s Hoppy Easter, which they describe as a “German-style IPA.” Some contain herbs and spices: Jacobsen’s Forårsbryg uses the spicy woodland herb woodruff, famous as a seasoning in May wine and as an herbal syrup for Berliner Weisse; Vendia’s version incorporates elderflowers, a popular flavor up north; Det Lille uses sweet orange and a bit of star anise in theirs.

Easter beers in the North American brewing tradition existed, as old labels will verify, but there is little evidence that these were ever a distinct style. There are precious few spring-specific brews in the United States these days; the Bruery’s Saison de Lente is a fine exception.

My own mother was raised on chocolate and Coca-Cola. She liked a little wine but didn’t discover beer until I was a published beer geek. When she did, her tastes remained with the flavors of her childhood. The more a beer tasted like chocolate, or really any kind of dessert, the better she liked it. Rather than stick my neck out and say what women want — an old Arab proverb says it is “toasted ice” — I’ll just pick out a few brews I wish I could have poured for her before she passed.

No actual chocolate present, but plenty of rich, dark complexity in this creamy milk stout. An everyday tipple for the sweet-toothed. 5.2% ABV.

Deep, dark, and softly chocolatey. A world-class Trappist ale brewed with lots of dark caramel syrup. 11.3% ABV.

Like spiced toffee, with a sweet, cake-like finish. 8.5% ABV.

Just exactly like a chocolate-covered cherry. Luscious! 6% ABV.

An astoundingly complex oak-aged golden wheat wine with cacao nibs. Will benefit from some aging. 14.75% ABV.

Massive attack of everything dark and sweet, with vanilla and bourbon overtones — like melted chocolate ice cream. 9.5% ABV.

The Brewers Association hosts this lavish and upscale presentation of beer in a fine-food context, with selected breweries in a festival setting and food pairings at every table. Brewery staff is on hand so you can meet your heroes or just chat about the beers. Event locations (New York City or Washington, D.C.) and dates change to some degree, but it’s usually around the second weekend of May.

Held at Lake Casitas, near the resort town of Ojai, a bit north of Los Angeles, this is the original outdoor homebrewing campfest. Grown to over 2,000 members-only attendees (you can join, you know), this event sponsored by the Southern California Homebrewers Association features the usual: beer, fun, food, homebrewing competition, presentations, live music, and plenty of easy homebrew camaraderie. Shuttles to nearby hotels are available for the camping-impaired. First weekend in May.

It’s not exactly a beer festival, but it is one of the more enjoyable things a beer lover can do on the first Saturday in May. Sponsored by the American Homebrewers Association, this is a national event celebrated at hundreds of different locations, including in private homes and commercial breweries. It’s a great opportunity to get connected to the club in your region.

Maui Brewers Festival, Maui, Hawaii; Boonville Beer Festival in beautiful Anderson Valley, Mendocino County, California; Los Angeles Vegan Beer & Food Festival, West Hollywood, California; Southern California Homebrewers Festival, Lake Casitas, California; PA Flavor: A Celebration of Food & Beer, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Great Australasian Beer SpecTAPular, Melbourne, Australia; Beer Advocate’s American Craft Beer Fest (ACBF), Boston, Massachusetts; Virginia Beer Festival, Norfolk, Virginia; California Festival of Beers, Luis Obispo, California; Copenhagen Beer Festival, Denmark; Ceský Pivní Festival, Prague, Czech Republic; The Cambridge UK Beer Festival, Great Britain; The Wien Bierfest, Vienna, Austria

Fred Eckhardt is the distinguished, rabble-rousing beer author and homebrewing pioneer. Celebrate with friends over a cool glass of homebrew, or come out to the extravaganza that is FredFest, a charity beer event celebrating Fred in his hometown of Portland, Oregon.

This is not a festival or a city-based beer week, but rather a nationwide celebration of American craft beer promoted by the Brewers Association, the trade group representing craft brewers in the United States. Check the craftbeer.com website for listings of hundreds of tastings, special events, and the synchronized toast to celebrate the new American beer freedom. It’s usually the third week of May.