Chapter Eight

The Provence Of Jean Giono And Henri Bosco

This chapter is concerned mainly with the hilly and mountainous areas north and north-east of Aix-en-Provence, places often written about by the novelists Henri Bosco and Jean Giono. Bosco knew especially the southern flank of the Montagne du Luberon (sometimes written “Lubéron”), Giono its eastern edge and the Montagne de Lure. Giono contrasted his landscape of high mountains and high plateaux, “hard, dry stone... olive and almond-trees” with Bosco’s “undulating hills” and rich, fertile plains. If sometimes the characters in their books seem to be alike, that is because they are “deep-rooted” in the earth, “but chez lui there is plenty of water. My characters are looking for it, or conserving it.”

The distinctive shape of the Luberon has prompted many a simile and metaphor. Bosco sees, near Lourmarin, “the silhouette of a sleeping beast”. For John and Pat Underwood (Landscapes of Western Provence and Languedoc-Roussillon, 2004) it is more specifically “a giant cat in slumber”. Maurice Lever, in his biography of the Marquis de Sade, goes to extravagant lengths: seen from La Coste the mountain looks like an eagle with “an enormous wingspan”, the wings hiding its head—or perhaps the village of Oppède is its stone beak. Only one of its eyes is closed and it could fly off at any moment. For Albert Camus, when he lived at Lourmarin, the Luberon was, perhaps more interestingly, “an enormous block of silence that I listen to endlessly.” The more remote Montagne de Lure has attracted less literary attention, but Giono once called it “the monstrous backbone of Dionysos’ bull.”

In the mid-sixteenth century a number of villages on and near the Luberon fell victim to brute, unmetaphorical fact. In 1540 nineteen Vaudois or Waldensians from Mérindol, members of a mainly peasant sect whose origins went back to the twelfth century, were condemned to be burnt at the stake in Aix. Their village was also to be destroyed. Appeals to the crown continually delayed the sentence from being carried out, but fighting between Catholic and Vaudois villages began to flare up in 1543. The bishop of Cavaillon launched an attack on Cabrières d’Aigues. Vaudois raiders sacked the Abbey of Sénanque and hanged twelve monks. And then Jean Meynier, Baron d’Oppède, took on the task of rooting the heresy out. He and his associates were also eager to seize some land. During a few bloody days in April 1545 his army killed about 3,000 people, committed many rapes, and took about 600 prisoners who were sent to the galleys. They fired Mérindol, most of whose inhabitants had fled; its ruins remain near the modern village. There were terrible massacres at Cabrières d’Aigues, Cabrières d’Avignon, and Lourmarin. Having smashed up Cabrières d’Avignon, the persecutors inscribed on what was left of the main gate: “Cabrières, for having dared to resist God, has been punished.” Meynier d’Oppède was eventually brought to trial in 1549 but was swiftly acquitted. Many Vaudois fought on, using the mountain terrain to advantage as would the Resistance 400 years later. The Vaudois struggle fed into the wider Wars of Religion of the 1560s onwards—the Vaudois leaders were in close contact with the Calvinists from the 1530s and later, at least in France, tended to merge with them. And there was a legacy of distrust between Catholic and Protestant villages in the Luberon which diminished only in quite recent times.

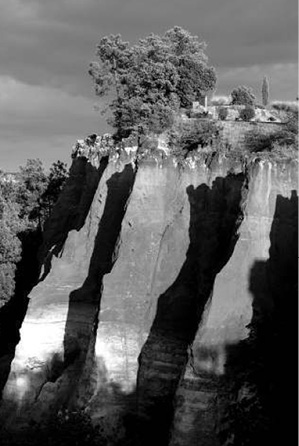

Roussillon

The village of Roussillon takes its name from its cliffs and quarries of red ochre; locally the industry produces about 3,000 tonnes a year. Seventeen shades of red have been observed. Such a landscape was, not surprisingly, simply “trop déclamatoire” for Samuel Beckett. (His remark is reported in James Knowlson’s Damned to Fame: the Life of Samuel Beckett, 1996.)

Beckett and Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil (later his wife) lived in Roussillon, in a house on the road to Apt, between 1942 and 1944. They had narrowly escaped to Vichy France, with the help of friends, when the Germans uncovered the Resistance cell they belonged to in Paris. During his time in the village Beckett did heavy work on farms and vineyards in exchange for food and drink, and wrote much of Watt (1953), “partly,” as Knowlson says in his article on Beckett in the Dictionary of National Biography, “as a stylistic exercise and partly in order to stay sane in a place where he was cut off from most intellectual pursuits.” The novel is, appropriately to this period in the life of Beckett and of France, full of uncertainties. He also helped the local Resistance, who remained unaware of his previous experience in Paris. He was involved mainly in transporting weapons and radio components dropped by the RAF and hiding explosives in his house; he received training in the use of rifle and grenades but was glad he never had the opportunity to use them. He intensely disliked violence and claimed to his friend Lawrence Harvey that he was “lily-livered”. But his fellow maquisards or Resistamce fighters respected him enough to have him lead the liberation procession into the village, vigorously waving the French flag and singing the Marseillaise: a somewhat unfamiliar image of the playwright. Obviously he was relieved that the long years of isolation, of waiting, were over—almost that he was moving out of the world of Waiting for Godot, in whose original French version (1952) Vladimir mentions grape-picking in Roussillon, down there where “everything’s red”; but if they were there at all Estragon “noticed nothing.”

The village soon returned to its less flag-waving everyday life. Laurence Wylie, the American sociologist who studied Roussillon in 1950-1 for Village in the Vaucluse (1957), found people “haunted by despair”. There was much “nostalgic yearning” for an earlier communal life; Roussillonnais who were “traditionally inclined to accept the worst with a fatalistic shrug... found little to hope for in the gloomy future. “‘On est foutu! (We’re done for!)... Why should I plant fruit trees?’ said Jacques Baudot. ‘So the Russians and the Americans can use my orchard for a battleground? No thanks’.” But when he came back ten years later Wylie encountered less emphasis on the past and a greater optimism about the future: “Baudot took me to see the apple and apricot trees he had planted... There was no more talk about being ‘done for’.”

Lourmarin

At the end of his life Albert Camus (1913-60) lived mostly in the Grand’rue de l’Eglise, Lourmarin. In his unfinished novel Le Premier homme he wrote about the heat and light of his native Algeria and—at least as much of a contrast with the hills of Provence—”that cramped, flat country full of ugly villages and houses which extends from Paris to the Channel” through which Jacques Cormery travels one pale spring afternoon on the way to visit the grave of his father. Camus himself is buried in the cemetery at Lourmarin; he died in a car-crash on the way to Paris on 4 January 1960 with the manuscript of the novel in his briefcase. In 1967 a bas-relief of Camus’ head was added to the village fountain, with an aptly existential inscription from his Myth of Sisyphus: “The struggle towards the summit, in itself, is enough to fill a man’s heart.”

The novelist Henri Bosco (1886-1975), who was connected with the Luberon for much longer, is also buried here. His first novel Pierre Lampédouze (1924) ends with the troubled hero’s consoling vision of the landscape from the terrace of the château. (Bosco knew Robert Laurent- Vibert, who restored the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century château before his death in 1925, and became one of the trustees of the subsequent Laurent-Vibert arts foundation, which is still based there.) In the more famous Le Mas Théotime (1945) the setting, although the place-names are changed, is recognizably the countryside around Lourmarin. And it is the land which plays as great a part as the characters in this and much of Bosco’s work.

The narrator Pascal and his tenant farmers the Alibert family are engaged, season by season, in a long struggle with the soil they nevertheless love. If, as Bosco said in an interview reported by Robert Ytier (Henri Bosco ou l’amour de la vie, 1997), you let yourself be taken over by the sauvagerie of the land—stop loving it—you “go mad, lose all sense of proportion and destroy yourself,” like Pascal’s hostile, misanthropic cousin and neighbour Clodius. But even Clodius feels a bond to the land: he neglects but fiercely defends his farm, and wills it to the hated Pascal rather than letting it pass out of the family.

Pascal is aware that he shares something of Clodius’ sauvagerie. His frequent desire to be alone, to preserve some private space in the mas, both complicates and helps him survive his relationship with another, more sympathetic cousin, Geneviève. He loves her yet—she is wild in her own way and still married to another man—cannot move into a full or permanent relationship with her. Her intuition and unpredictability make her, often, a woman very much as we might expect a man of Bosco’s generation to see her. “Perhaps she realized,” we are told, “that a woman can never achieve” complete control over herself; to find herself she needed “the love of a man”.

Lourmarin, where Albert Camus would “listen” to the

Luberon, “an enormous block of silence.”

Hard work on the land and an almost mystical devotion to the mas heals Pascal, prevents him giving way to his feelings when Geneviève leaves. As he comes back to Théotime in the half-light on one occasion he perceives it as a moral and religious entity as much as a physical: “It was an old house of goodness and of honour, a house of bread and of prayer.” Although the name Théotime comes directly from Pascal’s uncle, it also means, he points out, “you will honour me as a god.” Later he explains the mutuality of his relationship with the place: in him “it is naturally Théotime which thinks, loves, wants,” and he will undertake nothing contrary to its laws, however difficult the violence of his desires sometimes makes this. And so the many descriptions of the place—this is a slow-moving, ruminative novel—seem often to take us beyond the purely physical; at dawn the light seems not to be reflected from the tiles but “to emanate mysteriously from their porous clay.”

Pascal’s destiny is not with the fascinating, troubled Geneviève but with the Aliberts and their daughter Françoise, who are silent by preference and completely dedicated to the land and the work. In the end “the land saved me.”

Lacoste: “Making A Spectacle Of Oneself “

In 1765 Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) ,arrived at one of his main ancestral residences, the medieval and Renaissance château of La Coste (now usually written Lacoste). Defiant, as ever, of public opinion, he came not with his wife but with his current lover, the actress Mlle Beauvoisin. His vassals turned out to welcome their lord and, they assumed, their new lady, in song.

Sade finally brought his Marquise to La Coste in 1771; perhaps one fine lady looked much like another to the villagers. A few years earlier he had begun to fit out a theatre in the château and his main aim now was to organize an ambitious season of productions. The theatre could seat an audience of sixty people and had standing-room for sixty more. The scene showed a salon, as convention dictated, but could be altered with backdrops to become a public square or a prison. (Nobody can resist remarking on the prison. Sade had already been arrested for involvement in one sexual scandal and would spend twenty-nine of his remaining years in prisons and mental institutions.) The theatre was well lit with candles and lamps and the blue stage curtain could be operated—a great sophistication for the time—from the foyer.

The season, with Sade as director and often as one of the actors, was to last six months, beginning in May 1772. Twenty-four plays were to be performed in pairs first at La Coste and then a few days later at Mazan, another family property where he had installed a theatre. The repertory was mostly modern, including pieces by Diderot and Voltaire which were not, in the event, performed. Without care for the cost, Sade hired professional actors from Marseille and repeatedly moved them, and a considerable retinue, between the two venues. He, the Marquise and her sister Anne-Prospère de Launay also took part in at least some of the plays. As often—frequently in more controversial circumstances—Sade pressed hard at the boundaries between performance and reality. He cast his sister-in-law as the heroine of his own play Le Mariage du siècle with himself as her husband and his wife as her confidante. At the same time he embarked on an affair with his co-star—perversely attracted off-stage, no doubt, by her nun’s habit (she was in minor orders) and the element of incest, but also by the theatrical and erotic thrill of performing with her.

Sade’s fellow aristocrats seem to have been reluctant to come to his productions at La Coste and Mazan. He therefore found himself welcoming a less socially exalted audience, made up of more or less anyone he could persuade to come. This tended to confirm the view of his wife’s mother, Mme de Montreuil, who lamented to his uncle the Abbé de Sade that such spectacles are all very well at home among equals but that it is quite ridiculous “when someone makes a spectacle of himself in front of a whole province.” Actors are paid to entertain people of the Marquis’ rank in society, not to perform on an equal footing. Up to a point, she says, he can do as he likes, but he must not go on compromising her daughters by involving them. (She did not, of course, know quite how involved was her daughter Anne-Prospère. There is some debate as to when exactly the Marquise found out.) Moreover the whole enterprise is, she is aware, mountingly expensive. Money is needed for actors, costumes, scene-changers, food and drink for cast and audience, candles, transport, and Sade has already, she points out, “diminished his fortune by every possible extravagance.”

By June 1772 it was apparent even to Sade that funds were running short and so he went to Marseille to raise money. But it was not finance that cut short his theatre festival. While in the city he decided to divert himself with some prostitutes. Allegedly—the full truth remains difficult to come at—he drugged them before using them in his customary scandalous way; they suffered after-effects and he was charged with poisoning them (and with sodomy). When he failed to give himself up, the Parlement in Aix condemned him to death and, in his absence, he was executed there in effigy in the Place des Prêcheurs. In September, after a period in hiding, he fled to Italy with his sister-in-law. She soon came back to La Coste while he moved on to Chambéry, then in the Kingdom of Sardinia. There in October he was arrested at the request of France. After five months in prison he escaped and went to La Coste in May 1773. An extraordinary cycle of arrest, escape and return had begun. In January 1774 a carefully organized police raid on the château seized some of Sade’s papers but missed the man himself. According to his wife, the arrest party burst in after dark, smashed open desks, burnt documents, and admitted that they had orders to kill the Marquis. Again he returned, fled, returned and further fortified the château, hired some new women who made fresh accusations against him. He escaped another raid and departed for Italy once again in the summer of 1775 but was soon back at La Coste.

In January 1777 Sade’s strange career almost came to an abrupt end. A certain Treillet appeared at the great gate of the château; he was the father of a girl the Marquis was suspected of seducing or trying to seduce, having hired her as a domestic. According to Treillet’s account Sade refused to let the girl leave and bundled him out of the door. The aggrieved father pulled out a pistol and tried to shoot him point-blank but the gun failed to go off. He came back later after drinking freely in the village (say his enemies) and talked to the Marquis through the door. He tried to shoot him again, this time through the window, but missed. Finally people more influential than Treillet caught up with Sade: Mme de Montreuil had him arrested in Paris through a royal lettre de cachet the following month. Although the 1772 charges against him were dropped on appeal, the lettre de cachet prevented his release. There was one last escape: he had been brought down to Aix as a prisoner for the appeal hearing, and on the way back north managed to evade his guards near Valence and persuade a boatman to take him cheaply down the Rhône to Avignon in an old leaky boat. Yet again he came back to La Coste. There he was finally captured in a night raid in August 1777 and began thirteen years of captivity at Vincennes, the Bastille and Charenton.

After his release in 1790 “Citizen Sade” became for a time a revolutionary judge in Paris and—too moderate for the liking of his colleagues and superiors, in fact no sadist—himself came near to being guillotined. Meanwhile, in September 1792, a mob looted and burnt the château of La Coste, sending it well on the way to its present ruined state. The loss was “above expression”, the Marquis told his lawyer Gaufridy in October: “There was enough in this one château to furnish six... The scoundrels smashed and broke what they could not carry. Apparently the département has given orders that everything [saved from the looters] should be taken to Marseille. And by what right? Am I not at my post?” Although the local authorities claimed that they had done everything they could to restore order, Sade remained angry that he—the former victim, at least as he saw it, of ancien régime “ministerial despotism”, and now the friend of revolution—should have been targeted as if he were any other traitorous aristocrat. He sold what was left of the château in 1796-7.

Ménerbes: “The Darling Buds Of Mayle”

This village is the main setting of Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence (1989) and Toujours Provence (1991). The eccentricities of the Provençal characters, the joys and perils of living abroad, truffle-hunting and the history of pastis, appealed to a wide audience, but there was condemnation of the books both by people who felt that this was an over-simplified, caricatured Provence and by those who blamed them for swamping the once-peaceful Ménerbes with visitors. A recent “caricature account of the region has proliferated to the author’s profit, but little to its advantage,” icily observes Ian Robertson’s Blue Guide: France. Private Eye seized on the satirical opportunity presented by the fact that Mayle had worked in advertising: in “A Year in Advertising” Pierre Maille “is a peasant from Provence. A year ago he decided to sell up his farmhouse and join an advertising agency in London.” His “warm and witty book” describes how well he adapts as—not quite the expected reversal—”the pace of life slows down.” Maille writes, breaking into “Franglais”, “of the glorious lunches:

Le déjeuner est magnifique. Il commence à midi and lasts until le soir. Mon favourite petit restaurant is dans Charlotte Street, where nous mangeons outside sur le pavement... It’s all here. Les meetings, les mobile phones, les bouteilles de champagne “on the client”.

When A Year in Provence reached television in 1993 the satirists returned to the fray. Mayles (more often known as Miles) Kington gave over “Let’s Parler Franglais” No.94 to an episode of “The Darling Buds of Mayle”, introduced by “silly French accordion music”. Inspector Morse—John Thaw starred in the dramatization—declares happily: “Ah, ici nous sommes en Provence. Ah, le food! Le vin! Le brandy! Et les tres amusant French locals, avec ses mosutaches [sic] et le fameux beret!” He faces the problem of “how can zees tres thin libre be strung out comme les oignons sur la bicyclette?” But somehow he gets to the end of the episode: “More silly accordion music. Loving shots of Provençal countryside.” (The articles were reprinted in A Gnome in Provence: the Best of Private Eye 1991-3, the work apparently of one Peter Maylionaire.)

Ménerbes has reminders of more serious business. The citadel was rebuilt after a long siege in the 1570s. Protestant forces had seized the village in 1573 and held it for six years in spite of vigorous attempts by papal and royal troops to dislodge them. The Castellet, another rebuilt defensive structure, was lived in by the painter Nicolas de Staël in 1953- 4. Ménerbes was also the birthplace of Clovis Hugues (1851-1907), the socialist poet and journalist who was imprisoned for four years for his involvement in the Marseille commune of 1870.

Céreste

René Char came here to convalesce after septicaemia in the summer of 1936. Having served in the army in 1939-40 he returned to his home in L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue but had to flee, having been denounced for anti- Fascist sentiments (he was tipped off by a well-disposed Vichy policeman that he was about to be arrested). He came back to the mountains, to Céreste, where he worked for the Resistance. As “Capitaine Alexandre” he led sabotage and other missions, operating across a large area of southern France. During 1943-4 he wrote a sequence of short diary entries or meditations on his experiences, Feuillets d’Hypnos. Partly published in a review in 1945, it attracted Albert Camus’ attention and he arranged for its publication by Gallimard.

In the Feuillets Char is able to talk about the stress that, as a commander, he had to hide from his men. It was essential to show even more courage, to eat and smoke evidently less, than those around him. He records a particularly harrowing instance of how strong and apparently unreasonable he had to be when, hidden only about 100 metres away, he was present at the execution of “B.”:

I had only to press the trigger of my Bren gun and he could have been saved. We were on the heights above Céreste, armed to the teeth and at least equal in numbers with the SS. They with no idea we were there. To the eyes all round imploring me to give the signal to open fire, I shook my head... The June sun chilled me to the bone… I didn’t give the signal because this village had to be spared [from German reprisals] at any cost… Perhaps he knew this, himself, at that last moment?

Manosque And Jean Giono

Jean Giono was born at 1 rue Torte, Manosque, in 1895, lived as a child and young man in rue Grande, and from 1929 in a house on the Mont d’Or, Le Parais, which can be visited; there is a more extensive museum and library at the Centre Jean Giono, near the Porte Saunerie—a medieval gate but, in Giono’s opinion, tripatouillé, “tampered with”, by municipal restorers.

The Porte Soubeyran survives as well as the Porte Saunerie and there are two interesting churches: the tenth-century and later Notre-Dame de Romigier with its miracle-working statue of the Virgin, and its traditional rival the Romanesque and Gothic St.-Sauveur. But for Giono Manosque was truly beautiful only before 1914, when its streets were full of horses and carts and sheep, the elms were full of nightingales and, he claims, a hermit on St.-Pancrace hill rang a bell when dangerous storms approached from the west. Part of his novel L’Hussard sur le toit (1951), however, is set in a less blissful nineteenth-century Manosque. Angélo, the hussar of the title, takes to the roofs after escaping from the violent and panic-stricken inhabitants who, during a cholera outbreak, imagine all outsiders to be intent on infecting their water-supply. From here he surveys the tiles and towers, and watches the collapse of new victims, the murder of another suspected poisoner, the cart-loads of corpses going by. By 1963, when Giono wrote about his home-town for Elle, it was, he said, dominated by “arrogant, hideous and flimsy” council-flats and other “humorous” examples of modern architecture. “The only architecture of any quality” is that of the surrounding hills and plateaux and wild places—the places he explores in much of his work.

One of the best known early novels, Regain (1930) concerns the repopulation and revival—regain—of the village of Aubignane. (It is based partly on Redortiers, a ruined village in the foothills of the Montagne de Lure. When Marcel Pagnol filmed the book in 1937 he built his own Aubignane in the Massif d’Allauch, much nearer to Marseille.) The revival of the place relies on that of the characters, especially Panturle, who as a result of his love for Arsule abandons hunting, cultivates the land instead, and rediscovers simple, natural joys. Que ma joie demeure (1935) develops some of these ideas further. Bobi has worked as a travelling solo acrobat, a sign of his lack of ties and his transformative ability: he can transform and control his own body and can bring joy to the joyless. This he seeks actively to do when he arrives, seemingly from nowhere, on the semi-fictional Plateau of Grémone. He arrives in the night and first meets Jourdan, ploughing in the starlight in mysterious expectation of a stranger’s coming. The context sounds messianic, but Bobi brings, at first, very simple joys: for instance he makes Jourdan see Orion as never before, shows how to perceive “Orion fleur de carotte”. More generally he encourages openness to nature as the way to remove the boredom and anxieties of the small community. A stag (rather comically to later ears, perhaps, “il s’appelle Antoine”) lives freely near the farms, spreading delight and representing other “great inner joys”: for Bobi “today the ‘stag’ consisted of tasting the taste of winter, the bare forest, the low clouds, walking in the mud... feeling cold in his nose, warmth [from his pipe] in his mouth.”

Does are brought in to give joy to the stag. Animals are respected, horses released from their stables to mate as they choose. Music, sex, the skilled handling of a scythe or a loom, can bring similarly intense pleasure. The new emphasis is on what will give joy rather than what is done out of dull habit or for unnecessary financial benefit only. After some discussion the people of the plateau—of whom there are idyllically few—agree to combine their arable land and to harvest it together. Their community is defined in opposition to the world of towns, heavy industry, war and money. (The small-scale, individual and country aspects differentiate Giono’s ideal from Communist orthodoxy.) Obviously this is a utopia, but it is a very concrete one. And the second half of the novel makes clear the limits of the human capacity to hold on to joy. Sexual love complicates the communal harmony and the individual freedom and results in a death where Bobi thought he was bringing only life. Yet a strong sense of utopian possibility remains.

Le Contadour: “Une Expérience À La Bobi”

The ideal community of the plateau in Que ma joie demeure was soon to have its non-fictional parallel. In September 1935, soon after finishing the novel, Giono went up to the plateau of Le Contadour to lead the first of what became twice-yearly gatherings (Easter and late summer), mostly of young people. They chose the hamlet of Le Contadour as their centre, apparently, because Giono had to stop there having fallen and hurt his knee. Some people camped, others slept in barns. Soon Giono and two friends bought a building known as “the Mill”.

The people who came to Le Contadour were united by a strong faith in pacifism. Later, somewhat embarrassed by the myth of the “mage” Giono which grew up, he said that “People have greatly exaggerated my ‘teaching’. It amounted to no more than going for walks, camping and eating the odd slice of saucisson together.” But he did have a considerable influence on those who walked and ate with him, many of whom might have been happy to call themselves his “followers”. Usually they were enthusiastic readers of his novels as well as committed anti-militarists. At times Giono did function very much as a guru. Photographs show him sagely smoking his pipe surrounded by younger visitors to Le Contadour. “For us, a new life has begun,” he wrote in his journal on 15 September 1935; they will have “une expérience à la Bobi”. Clearly he will, he hopes, be central to that experience, will be Bobi the bringer of joy.

The camping and the talking went on as the European crisis came to a head. Giono rained telegrams, pamphlets and declarations on the French, British and German governments. He was even involved, his friend and biographer Pierre Citron reports, in a wildly impractical plan to meet Hitler. Giono intended to put his point to him with the aid of an interpreter, who must, he would insist, be Jewish. One of his last desperate bids for peace, Recherche de la pureté (1939), emphasizes the horror and injustice of the First World War, in which he had fought; warriors are those “who do not have the courage to be pacifists.” The last “Contadour” was interrupted by the Nazi-Soviet pact, the invasion of Poland and the declaration of war. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Giono was arrested on 14 September and imprisoned in the Fort St.-Nicolas in Marseille. (Citron concludes that Giono did not, as he claimed, destroy his call-up papers. That story is one more example of his romantic myth- making.)

Giono was released, partly through the intervention of André Gide, in November 1939. He was arrested again, unjustly accused of collaboration, after the Liberation in 1944, and spent five months in prison. His later novels take a rather more oblique, ambivalent look at life than the earlier, more utopian tales: a metaphorical look, with his Hussar, from the roofs of Manosque.