According to Linn, Fabricant, and Linn (1988), in the early 1900s if you were born into an orphanage in the United States you were likely to be dead by the time you were two years old. This was according to a study done by Dr. Henry Chapin, a pediatrician in New York City. There was another pediatrician, Dr. Fritz Talbot, who found those statistics unacceptable. He discovered an orphanage in Dusseldorf, Germany where the mortality rate was the same as the general population, so he went to investigate. The doctor found that the orphanage followed very similar policies and procedures as those here in America with one small difference. There was an older woman named Anna, who carried a child on each hip. The director of the orphanage told Dr. Talbot, “When we have done everything medically possible for a baby, and it is still not doing well, we turn the child over to old Anna. Whenever a child cried the woman would pick the child up, hold him or her, and give motherly love. A few minutes with old Anna literally meant the difference between life and death for some kids.”

When this doctor came back to the United States, he shared his findings and several institutions recruited volunteers to do the same things Anna did. Not surprisingly in a very short time the mortality rate quickly became consistent with the general population.

Abandonment

Children who get their dependency needs met fully on a regular basis will thrive, flourish, and grow at a healthy pace. Life will be good for these kids. In the worst-case scenario, kids who do not get their needs met at all will experience a failure to thrive, and many will die. Let us use the analogy of an emotional gas tank; if our needs are met fully we feel full, complete, satisfied, content, and happy. If we don’t get our needs met at all we feel a great emptiness inside. I have heard this emptiness described in many ways: a black hole, a void, a vacuum, an ache, or a longing. Perhaps we get our needs met half-way; we feel half-full but something is missing, and we still feel an ache. These are emotional wounds, also known as original pain, and they result from an abandonment of our childhood dependency needs.

A Word about Blame

When parents do not meet the needs of their children, it is not usually because the parents don’t love them. I say “usually” because there are those cases that one cannot understand, accept, explain, or excuse for any reason. However, most parents do the best they can, given the internal and external resources they possess, to take care of their children. In fact, I cannot count the times I have heard parents say, “I try hard to make sure my kids have it better than I did.” This speaks very loudly to me. It says that these parents are familiar with unmet dependency needs. So, most often, it is not the parent’s lack of love or effort that is to blame. It is usually because of one of the following reasons that abandonment occurs:

1. Circumstances: For example, if one parent dies and the other must take two jobs to care for ten children, circumstances are to blame for this, not the parents. None-the-less the children get hurt in the process.

2. Wounded people wound people: Parents cannot demonstrate much more than they have been given. Our parents were raised by their parents who likely were also wounded, and they were raised by their parents, etc. Maybe dad is an alcoholic; he has a disease that impaired his ability function in his major life roles, including his ability to be the kind of father his kids need him to be. He did not aspire to become alcoholic. Alcoholism chooses you, you don’t choose it. Perhaps mom is so chronically depressed she can’t leave a dark room much less take care of anyone else; she didn’t choose that. However, the primary issue for parents is that they are wounded themselves, sometimes moderately, other times severely because their parents were also wounded, and their parents were wounded, etc. Whatever the issue, the result is wounded children.

Again, it is not usually a question of whether our parents loved us, or even if they did the best they could for us. Many people get stuck on this truth and end up saying, “So why go back and dig all that up? They did the best they could and that is that. You can’t change the past.” To those people, I say keep reading, this book will show you why it is important to “dig all that up.” Suffice it to say here that assigning blame is not the reason.

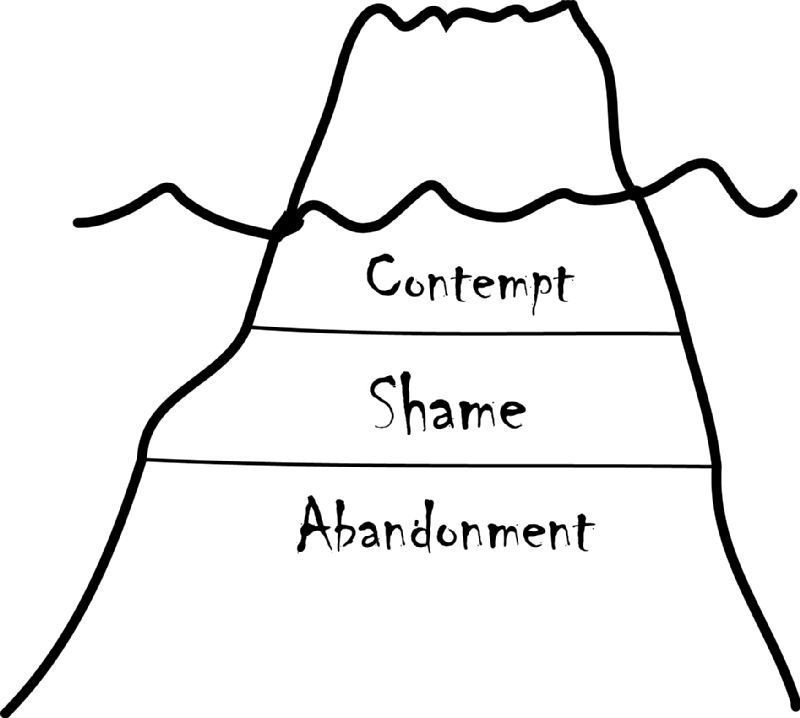

Children have not yet developed the skills to cope effectively with emotional pain. It seems they can handle a broken arm better than a broken heart. They rely heavily on a defense mechanism called repression to push the emotional wound deep into their unawareness [Fig. 2]. They also act-out their pain in various ways as a survival instinct which calls attention to it so the adults in their life can assess, diagnose, and respond to them. If the adults are unresponsive, and the child continues to experience abandonment the wounds accumulate.

Figure 2: The wound of abandonment

The extent of the wounds may be mild, moderate, or severe depending upon the extent of the abandonment. Mild to moderate cases of wounding comes from situations in which the child does not fully or consistently get their emotional dependency needs met. There may be few overt signs of family dysfunction or abuse. For instance, it may be that one or both parents are able to give reasonable amounts time, attention and direction but are unable to express affection. The words “I love you” may rarely be heard, if at all, in this family. A lack of hugs, kisses, and other forms of emotional warmth leave a child to wonder how they measure up in the eyes of their parents. It makes matters even worse when the child lives in a shame-based family system. In such families the children get messages of disapproval through constant criticism rather than messages of approval and warmth.

A shame-based family system is characterized by the parent’s use of shame to provide direction to the child. For instance, when a five-year-old child scrapes his knee the parent, or parents, might tell the child to stop crying because “Big boys don’t cry.” They may also simply ignore the child until he or she stops crying. Similarly, when the child makes a mistake the parent might say, “What’s wrong with you?” or “Why can’t you be more like your sister?”

Sometimes the shaming goes to extremes, especially when a wounded, shame-based parent is angry: “You are going to end up in prison!” “You’ll never amount to anything!” “You never were any good; why do you do this to me?” These comments are often accompanied by slaps or even punches from the parent. In shame-based families these types of comments and behaviors are often intended to “help” the child learn right from wrong. However, while the intended “help” may actually produce the intended result the next time, another result is emotional wounds for the child. Shame is discussed in more detail in the next section of this chapter.

Another common abandonment scenario occurs when one of the parents is physically absent much of the time. The parent may be a “workaholic” who cannot seem to stop working long enough to find time for his family. The workaholic rationalizes his absence and breaks promises to be there for the child in the same way an alcoholic rationalizes her drinking and breaks promises to stop or control it better.

By now, the reader may begin to suspect that abandonment and wounding must happen on some level to most, if not all, of us. I believe it is true that all of us experience emotional wounds in life, but not all of us experience abandonment. The best example is when we lose someone or something important to us. Grief is a natural part of living, and one cannot escape an encounter with it for long in this world. When someone or something becomes important to us, we bond with it on an emotional level. Emotional wounds result when this bond is breaking or broken. Grief is the process we must go through to let go of the attachment and heal from the resulting loss-related emotional wound.

The absence of a parent may be perfectly justifiable as when a military parent is abruptly deployed overseas for a year or longer. As already mentioned, little kids get it that parents love what they give their time to. So if the child gets little or no time from a parent, the child tends to experience it as little or no love, regardless of the reason for the absence. Whether or not it results in abandonment in the case of circumstantial, unavoidable, or justifiable absences, such as the above example of deployment, is determined by what happens before, during, and after the absence of the parent.

There has been much written that suggests the terms “abandonment” and “loss” are interchangeable. While both result in emotional wounds, the author believes they are not interchangeable terms and that an important distinction must be made. Abandonment always involves loss for the child, but loss does not always involve abandonment. Loss-related wounds can heal if the person possesses the psychological support and emotional coping skills necessary to aid in the grieving process. Children who have emotionally healthy, responsive parents tend to get their needs met consistently. Because of that, they are equipped either internally with their own coping skills (depending on their age) and/or externally with parents who are able to provide the necessary support through the grief process.

When children cannot put into words what they are experiencing, whether it be from abandonment or other significant losses, their pain must find expression somehow and does so through compulsive patterns of behavior commonly referred to as “acting-out.” When their needs are going unmet, children are compelled by instinct to act-out their needs through behaviors designed to elicit an appropriate response from caregivers, provided the caregivers are able to respond appropriately. If it is attention he need, the child’s behavior will be attention-seeking. If they need approval, the behavior will be approval-seeking. And if the child needs discipline his behavior will likely be discipline-seeking. It is as if the child is an actor in a play, hence the term “acting-out.” There are some clearly defined patterns of acting-out that not only help children find expressions for their pain but also actually help them to survive. We will discuss these patterns of behavior, better known as survival roles, in greater detail in the next chapter.

As already mentioned, young children do not possess the necessary skills to cope with emotional pain on their own. As with everything else they are dependent on their caretakers for help in grieving. The best children can do is to act-out their pain and hope their parents and other caretakers in their lives are healthy enough to notice the behavior, accurately assess the need, and respond accordingly. When parents possess the skills to respond consistently to their children’s needs for time, attention, affection, and direction, they are helping their children resolve the current episode of grief to some extent, as well as to build the internal structures necessary to cope effectively with grief and loss on their own later in life. When parents are not able to respond appropriately to the child’s need for help, loss-related wounds tend to accumulate right along with the wounds of abandonment, further complicating the child’s pain.

Severe cases of emotional wounding, also known as trauma, results in situations where children have experienced overt abuse or other major losses coupled with inadequate support to aid in their grief. The emotional trauma that comes from abuse violates not only the child’s emotional dependency needs but also his most basic needs, the survival dependency needs. This is especially true for their need to feel safe and protected. Imagine a child’s dilemma when he needs protection from the very people who are supposed to provide it. The following are some forms of abuse and/or major losses that produce moderate to severe emotional trauma in children:

Sexual and Physical Abuse

Emotional abuse or neglect: Emotionally unavailable parent(s) or parents who give their child the opposite of what they need such as name-calling, belittling, threats of abandonment, shaming, etc.

Psychological abuse: Ignoring the child as if she does not exist or denial of a child’s reality such as telling her they didn’t see what she saw (e.g., “Daddy wasn’t drunk, don’t you ever say that again!”)

Frequent Moves

Adoption Issues

Prolonged separation from a parent

Reversal of parent/child roles

Rigid family rules

Divorce

Death of a parent or other family member

Mentally Ill parent or family member

Cruel and Unusual punishment: such as locking a child in the closet.

Shame

As discussed in Chapter 1, it is imperative that children feel safe and protected as part of getting their survival needs met. In order to feel safe, even in an unsafe environment, children idealize their caretakers. In other words, little kids put their parents up on a pedestal and see them as perfect, all-knowing and all-powerful god-like creatures. Idealization is a defense mechanism that helps children feel safe because they get the feeling that nothing can get to them, since they are protected by a god.

Since god-like creatures are perfect, they are beyond reproach in the innocent mind of a child. Children cannot say to themselves, “Well, Dad has a drinking problem. That’s about him not me; I don’t have to take it personally when he breaks his promises and yells at me all the time.” No, in the mind of a child it goes more like this… “If I were a better kid Daddy wouldn’t drink.” or “If I was a better kid Mommy wouldn’t yell at me so much.” or the classic, “Daddy, please don’t leave, I’ll be good!”

Because of idealization, young children can make sense of it no other way; it has to be about them. Parents have all the power, and the child has none. They are totally submitted and committed to the parent. Thus, they develop a sense of defectiveness, and it begins to grow along with the wounds. So, if abandonment is an emotional wound, then shame is an emotional infection that sets in as the wound goes unattended [see Fig. 3]. This infection has a voice, and it grows stronger as the wounds accumulate. The child’s self-talk begins to sound like this, “No one could ever love me.” “I don’t count.” “What’s wrong with me?” “I’m stupid, lazy, unworthy of anyone’s attention.”

Figure 3: The infection of shame

In a shame-based family system, these internal messages of shame are actually confirmed by the parents. Sometimes the confirmations are more subtle and come in veiled threats of abandonment, double-bind messages, gestures that convey contempt for the child and other nonverbal expressions of disdain. Other times the confirmations are directly stated through name-calling, belittling, and emotional battering such as “You’re stupid, ugly, lazy, fat,” etc. “No one could love you.” “You can’t do anything right.” These messages result in what John Bradshaw (2005) has termed “toxic shame” in his book Healing the Shame that Binds You. Of course, these messages frequently come with a misguided positive intention to motivate the child.

The infection of shame exacerbates the wounds of abandonment, and the pain grows. In the worst-case scenarios, such as sexual abuse or incest, toxic shame is a byproduct regardless of the messages a child received before the abuse occurred, or after it ended.

Contempt

In keeping with the analogy of a wound, contempt is the scab that forms over the infection of shame and the wound of abandonment [see Fig. 4]. The scab of contempt consists of all the “crusty” feelings of anger, resentment, and bitterness. It is what the child is most aware of, and it skews his whole experience of life as well as his role in it. Some call it the “life sucks” syndrome. The negative energy from the contempt must be directed somewhere. There are two possible choices, and the choice is made at an unconscious level. The energy can be directed inward in the form of self-contempt; or outward as contempt for people, society, authority figures, the opposite sex, or whoever is available, including God.

If we have a tendency to point the contempt inward at self, we are internalizing it. If we are more likely to turn it outward toward others, we are externalizing the contempt. The self-talk of an Internalizer is all about the defectiveness of self and his or her unworthiness to exist, leading to inappropriate guilt, and more shame, making the emotional infection worse. The self-talk of the Externalizer is all about the defectiveness of others and the unfairness of it all, leading to inappropriate anger.

Figure 4: The scab of contempt

Many of us will internalize the contempt until we can’t take it anymore and then blow up, directing it outward in an attempt to ventilate. When we externalize or “dump” our contempt it lands on whoever is nearby, usually those who are closest to us. Then, because we have hurt someone we love, we turn the contempt back on ourselves through more shame-based messages such as, “See there. I’ve done it again … I’ve hurt someone I care about! I’ve proven it this time … I really am a loser!” Internalizing the contempt feeds the infection of shame, speeding up its progression and the power it has over us.

Some people tend to internalize their contempt while others tend to externalize it. People who are primarily Internalizers have problems with depression, caretaking, approval-seeking, lack of adequate boundaries, and lack of a sense of personal power. They have difficulty saying, “no” because that may bring disapproval, which is extremely anxiety-provoking since it is the opposite of what they seek. Persons that are predominantly Externalizers are less likely to be aware of their behavior and the effect it has on others. They believe other people should do things their way, tend to be self-centered, intrusive, have rigid boundaries, may have an excessive need to be right, and proclaim that they don’t need anyone.

Externalizers have a tendency to demonstrate what Bradshaw calls “shameless behavior.” Shameless behavior is seen in situations of abuse where the abuser is exercising god-like control over the victim. Examples of shameless behavior include sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. Shameless Externalizers develop a very thick scab. In the extreme cases, the person involved in shameless behavior is unaware on a conscious level that his behavior is wrong or sometimes even that it is hurtful to the victim. On an unconscious level, Externalizers cannot escape the reality of their behavior or its impact on the victim. The unconscious mind knows all; the shame, guilt, and remorse continue to accumulate for Externalizers, even though they are largely unaware of it. As their infection of shame grows, so does their contempt along with the need to externalize it. This build-up of contempt may eventually lead the Externalizer to episodes of the violent and/or dangerous behavior described earlier in this chapter.

The False Self

The wound of abandonment, the infection of shame, and the scab of contempt forms a free-floating mass of pain just beneath the surface of our awareness which creates in a child a false sense of identity – A False Self [see Fig. 5].

Figure 5: The False Self

The term “False Self” is used because it is just that–false, not true; a counterfeit self. It really feels like who we are, whether we were the child back there-and-then or the adult reading this book here-and-now. But this is not who we really are, and I hope to prove that in a moment. It feels that way because the wound is emotional in nature. Despite our best efforts, we cannot simply transfer the intellectual reality of this truth to our emotional reality. It is not until significant healing of the emotional wounds takes place that we are able to feel differently about ourselves.

Many times we have heard the saying, “kids are resilient.” This is likely an effort to minimize our own guilt about not having been able to protect and/or nurture them the way they needed. While it is true that kids are resilient, the implication that they are now fine and have bounced back is not accurate. Emotional wounds do not go away. They must be tended to just like any other wound or the infection grows, and it gets worse. “Kids are survivors” is a more accurate statement. In the next chapter, we begin to explore how a child learns to survive and even get some of her needs met despite difficult circumstances. The skills they learn help them to survive, but they don’t go very far in helping them effectively cope with adult life or have an intimate relationship.

Again, if you are a parent, please stay with your feelings about your own childhood experiences as much as possible as you read. Try to avoid getting lost in worry or guilt over your children. There is good news to come. For now, keep in mind that the best way to help them is to help you first. They learn by watching what you do, so demonstrate for them how to heal. Yes, get them into counseling if they need it and pay attention to their behavior if they are acting out. However, take care of yourself in the process too.